The Agent Orange Act of 1991—Public Law (PL) 102-4, enacted February 6, 1991, and codified as Section 1116 of Title 38 of the United States Code—directed the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to ask the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to conduct an independent comprehensive review and evaluation of scientific and medical information regarding the health effects of exposure to herbicides used during military operations in Vietnam. The herbicides picloram and cacodylic acid were to be addressed, as were chemicals in various formulations that contain the herbicides 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T). 2,4,5-T contained the contaminant 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, referred to in this report as TCDD to represent a single—and the most toxic—congener of the tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxins (tetraCDDs), also commonly referred to as dioxin. It should be noted that TCDD and Agent Orange are not the same. NAS also was asked to recommend, as appropriate, additional studies to resolve continuing scientific uncertainties and to comment on particular programs mandated in the law. The legislation called for biennial reviews of newly available information for a period of 10 years; the period was extended to 2014 by the Veterans Education and Benefits Expansion Act of 2001 (PL 107-103).

In response to the request from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies convened the Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides. The results of the original committee’s work were published in 1994 as Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam, hereafter referred to as VAO (IOM, 1994). Successor committees formed to fulfill the requirement for updated reviews produced Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 1996 (IOM,

1996), Update 1998 (IOM, 1999), Update 2000 (IOM, 2001), Update 2002 (IOM, 2003a), Update 2004 (IOM, 2005a), Update 2006 (IOM, 2007), Update 2008 (IOM, 2009), and Update 2010 (IOM, 2011).

In 1999, VA asked the IOM to convene a committee to conduct an interim review of type 2 diabetes associated with exposure to any of the chemicals of interest (COIs); that effort resulted in the report Veterans and Agent Orange: Herbicide/Dioxin Exposure and Type 2 Diabetes, hereafter referred to as Type 2 Diabetes (IOM, 2000). In 2001, VA asked the IOM to convene a committee to conduct an interim review of childhood acute myelogenous leukemia (AML, now preferably referred to as acute myeloid leukemia) associated with parental exposure to any of the COIs; the committee’s review of the literature, including literature available since the review for Update 2000, was published as Veterans and Agent Orange: Herbicide/Dioxin Exposure and Acute Myelogenous Leukemia in the Children of Vietnam Veterans, hereafter referred to as Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (IOM, 2002). In PL 107-103, passed in 2001, Congress directed the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to ask NAS to review “available scientific literature on the effects of exposure to an herbicide agent containing dioxin on the development of respiratory cancers in humans” and to address “whether it is possible to identify a period of time after exposure to herbicides after which a presumption of service-connection” of the disease would not be warranted; the result of that effort was Veterans and Agent Orange: Length of Presumptive Period for Association Between Exposure and Respiratory Cancer, hereafter referred to as Respiratory Cancer (IOM, 2004).

In conducting their work, the committees responsible for those reports operated independently of VA and other government agencies. They were not asked to and did not make judgments regarding specific cases in which individual Vietnam veterans have claimed injury from herbicide exposure. The reports were intended to provide scientific information for the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to consider as VA exercises its responsibilities to Vietnam veterans. This VAO update and all previous VAO reports are freely accessible online at the National Academies Press’s website (http://www.nap.edu).

In accordance with PL 102-4, the committee was asked to “determine (to the extent that available scientific data permit meaningful determinations)” the following regarding associations between specific health outcomes and exposure to TCDD and other chemicals in the herbicides used by the military in Vietnam:

A) whether a statistical association with herbicide exposure exists, taking into account the strength of the scientific evidence and the appropriateness of the statistical and epidemiological methods used to detect the association;

B) the increased risk of the disease among those exposed to herbicides during service in the Republic of Vietnam during the Vietnam era; and

C) whether there exists a plausible biological mechanism or other evidence of a causal relationship between herbicide exposure and the disease. [PL 102-4, Section 3 (d)]

The committee notes that as a consequence of congressional and judicial history, both its congressional mandate and the statement of task are phrased with the target of evaluation being “association” between exposure and health outcomes, although biologic mechanism and causal relationship are also mentioned as part of the evaluation in Article C. As used technically and as thoroughly addressed in a report on decision making (IOM, 2008) and in the section “Evaluation of the Evidence” in Chapter 2 of Update 2010 (IOM, 2011), the criteria for causation do not themselves constitute a set checklist, but they are somewhat more stringent than those for association. The unique mandate of VAO committees to evaluate association rather than causation means that the approach delineated in the IOM report on decision making (IOM, 2008) is not entirely applicable here. The rigor of the evidentiary database needed to support a finding of statistical association is weaker than that to support causality; however, positive findings on any of the indicators for causality would strengthen a conviction that an observed statistical association was reliable. In accord with its charge, the committee examined a variety of indicators appropriate for the task, including factors commonly used to evaluate statistical associations—such as the adequacy of control for bias and confounding and the likelihood that an observed association could be explained by chance—and it assessed evidence concerning biologic plausibility derived from laboratory findings in cell culture or animal models. The full array of indicators examined was used to categorize the strength of the evidence. In particular, associations that manifested multiple indicators were interpreted as having stronger scientific support. Table 1-1 presents the starting point for this committee’s deliberations, namely, the cumulative findings of VAO committees through Update 2010 derived using this approach. (The current committee has not modified the criteria used by previous VAO committees to assign categories of association to particular health outcomes but will henceforth state the object of its evaluation to be “scientifically relevant association” in order to clarify that the strength of evidence evaluated, based on the quality of the scientific studies reviewed, was a fundamental component of the committee’s deliberations to address the imprecisely defined legislative target of “statistical association.”)

Following delivery of the committee’s charge by a VA representative at the first meeting, the open session continued with brief presentations by other members of the public. It has been the practice of VAO committees to conduct open sessions, not only to gather additional information from people who have particular expertise on points that arise during deliberations but also especially to hear from individual Vietnam veterans and others concerned about aspects of

TABLE 1-1 Summary from Update 2010 (Eighth Biennial Update) of Findings of Veterans, Occupational, and Environmental Studies Regarding AssociationsaBetween Exposure to Herbicides and Specific Health Outcomesb

Sufficient Evidence of an Association

Epidemiologic evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a positive association. That is, a positive association has been observed between exposure to herbicides and the outcome in studies in which chance, bias, and confounding could be ruled out with reasonable confidence.c For example, if several small studies that are free of bias and confounding show an association that is consistent in magnitude and direction, there could be sufficient evidence of an association. There is sufficient evidence of an association between exposure to the chemicals of interest and the following health outcomes:

Soft-tissue sarcoma (including heart)

* Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

* Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (including hairy cell leukemia and other chronic B-cell leukemias)

* Hodgkin lymphoma

Chloracne

Limited or Suggestive Evidence of an Association

Epidemiologic evidence suggests an association between exposure to herbicides and the outcome, but a firm conclusion is limited because chance, bias, and confounding could not be ruled out with confidence.b For example, a well-conducted study with strong findings in accord with less compelling results from studies of populations with similar exposures could constitute such evidence. There is limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to the chemicals of interest and the following health outcomes:

Laryngeal cancer

Cancer of the lung, bronchus, or trachea

Prostate cancer

* Multiple myeloma

* AL amyloidosis

Early-onset peripheral neuropathy (category clarification from Update 2008)

Parkinson disease

Porphyria cutanea tarda

Hypertension

Ischemic heart disease

Type 2 diabetes (mellitus)

Spina bifida in offspring of exposed people

Inadequate or Insufficient Evidence to Determine an Association

The available epidemiologic studies are of insufficient quality, consistency, or statistical power to permit a conclusion regarding the presence or absence of an association. For example, studies fail to control for confounding, have inadequate exposure assessment, or fail to address latency. There is inadequate or insufficient evidence to determine association between exposure to the chemicals of interest and the following health outcomes that were explicitly reviewed:

Cancers of the oral cavity (including lips and tongue), pharynx (including tonsils), or nasal cavity (including ears and sinuses)

Cancers of the pleura, mediastinum, and other unspecified sites in the respiratory system and intrathoracic organs continued

Esophageal cancer

Stomach cancer

Colorectal cancer (including small intestine and anus)

Hepatobiliary cancers (liver, gallbladder, and bile ducts)

Pancreatic cancer

Bone and joint cancer

Melanoma

Nonmelanoma skin cancer (basal cell and squamous cell)

Breast cancer

Cancers of reproductive organs (cervix, uterus, ovary, testes, and penis; excluding prostate)

Urinary bladder cancer

Renal cancer (kidney and renal pelvis)

Cancers of brain and nervous system (including eye)

Endocrine cancers (thyroid, thymus, and other endocrine organs)

Leukemia (other than all chronic B-cell leukemias, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia and hairy cell leukemia)

Cancers at other and unspecified sites

Infertility

Spontaneous abortion (other than after paternal exposure to TCDD, which appears not to be associated)

Neonatal or infant death and stillbirth in offspring of exposed people

Low birth weight in offspring of exposed people

Birth defects (other than spina bifida) in offspring of exposed people

Childhood cancer (including acute myeloid leukemia) in offspring of exposed people

Neurobehavioral disorders (cognitive and neuropsychiatric)

Neurodegenerative diseases, excluding Parkinson disease

Chronic peripheral nervous system disorders

Hearing loss (newly addressed health outcome)

Respiratory disorders (wheeze or asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and farmer’s lung)

Gastrointestinal, metabolic, and digestive disorders (changes in hepatic enzymes, lipid abnormalities, and ulcers)

Immune system disorders (immune suppression, allergy, and autoimmunity)

Circulatory disorders (other than hypertension and ischemic heart disease)

Endometriosis

Effects on thyroid homeostasis

Eye problems (newly addressed health outcome)

Bone conditions (newly addressed health outcome)

This committee used a classification that spans the full array of cancers. However, reviews for nonmalignant conditions were conducted only if they were found to have been the subjects of epidemiologic investigation or at the request of the Department of Veterans Affairs. By default, any health outcome on which no epidemiologic information has been found falls into this category.

Limited or Suggestive Evidence of No Association

Several adequate studies, which cover the full range of human exposure, are consistent in not showing a positive association between any magnitude of exposure to a component of the herbicides of interest and the outcome. A conclusion of “no association” is inevitably limited to the conditions, exposures, and length of observation covered by the available studies. In addition, the

possibility of a very small increase in risk at the exposure studied can never be excluded. There is limited or suggestive evidence of no association between exposure to the herbicide component of interest and the following health outcomes:

Spontaneous abortion after paternal exposure to TCDD

aThis table is the product of the committee for Update 2010; the current committee has decided to add “scientifically relevant” before “association” in its own work product to emphasize the scientific nature of the VAO task and procedures without implying any change in the present committee’s criteria from those used in previous updates.

bHerbicides indicates the following chemicals of interest: 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T) and its contaminant 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin), cacodylic acid, and picloram. The evidence regarding association was drawn from occupational, environmental, and veteran studies in which people were exposed to the herbicides used in Vietnam, to their components, or to their contaminants.

cEvidence for an association is strengthened by experimental data supporting biologic plausibility, but its absence would not detract from the epidemiologic evidence.

*The committee notes the consistency of these findings with the biologic understanding of the clonal derivation of lymphohematopoietic cancers that is the basis of the World Health Organization classification system.

their health experience that may be service-related. Open sessions were held during the first four of the committee’s five meetings, and the agendas and the issues raised are presented in Appendix A. The comments and information provided by the public were used to identify information gaps in the literature regarding specific health outcomes of concern to Vietnam veterans.Chapter 2 provides details of the committee’s approach to its charge and the methods that it used in reaching conclusions.

CONCLUSIONS OF PREVIOUS VETERANS AND AGENT ORANGE REPORTS

Health Outcomes

VAO, Update 1996, Update 1998, Update 2000, Update 2002, Update 2004, Type 2 Diabetes, Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, Respiratory Cancer, Update 2006, Update 2008, and Update 2010 contain detailed reviews of the scientific studies evaluated by the committees and their implications for cancer, reproductive and developmental effects, neurologic disorders, and other health effects.

The original VAO committee addressed the statutory mandate to evaluate the association between herbicide exposure and individual health conditions by assigning each of the health outcomes under study to one of four categories on the basis of the epidemiologic evidence reviewed. The categories were adapted from the ones used by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in evaluating

evidence of the carcinogenicity of various substances (IARC, 1977). Successor VAO committees adopted the same categories.

The question of whether the committee should be considering statistical association rather than causality has been controversial. In legal proceedings that predated passage of the legislation that mandated the VAO series of reviews, Nehmer v United States Veterans Administration (712 F. Supp. 1404, 1989) found that:

the legislative history, and prior VA and congressional practice, support our finding that Congress intended that the Administrator predicate service connection upon a finding of a significant statistical association between dioxin exposure and various diseases. We hold that the VA erred by requiring proof of a causal relationship.

The committee believes that the categorization of strength of evidence as shown in Table 1-1 is consistent with that court ruling. In particular, the ruling does not preclude the consideration of the factors usually assessed in determining a causal relationship (Hill, 1965; IOM, 2008) as indicators of the strength of scientific evidence of an association. In accord with the court ruling, the committee was not seeking proof of a causal relationship, but any information that supports a causal relationship, such as a plausible biologic mechanism as specified in Article C of the charge to the committee, would also lend credence to the reliability of an observed association. Understanding of causal relationships is the ultimate objective of science, whereas the committee’s goal of assessing statistical association is an intermediate (less well-defined) point along a continuum between no association and causality.

The categories, the criteria for assigning a particular health outcome to a category, and the health outcomes that have been assigned to the categories in past updates are discussed below. Table 1-1 summarizes the conclusions of Update 2010 regarding associations between health outcomes and exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam or to any of their components or contaminants. That integration of the literature through September 2010 served as the starting point for the current committee’s deliberations. It should be noted that the categories of association concern the occurrence of health outcomes in human populations in relation to chemical exposure; they do not address the likelihood that any individual’s health problem is associated with or caused by the chemicals in question.

Health Outcomes with Sufficient Evidence of an Association

In this category, a positive association between herbicides and the outcome must be observed in epidemiologic studies in which chance, bias, and confounding can be ruled out with reasonable confidence. The committee regarded evidence from several studies that satisfactorily addressed bias and confounding and

that show an association that is consistent in magnitude and direction as sufficient evidence of an association. Experimental data supporting biologic plausibility strengthen evidence of an association but are not a prerequisite.

The original VAO committee found sufficient evidence of an association between exposure to herbicides and three cancers—soft-tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma—and two other health outcomes, chloracne and porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). After reviewing all the literature available in 1995, the committee responsible for Update 1996 concluded that the statistical evidence still supported that classification for the three cancers and chloracne but that the evidence of an association with PCT warranted its being placed in the category of limited or suggestive evidence of an association with exposure. No changes were made in this category in Update 1998 or Update 2000.

As the committee responsible for Update 2002 began its work, VA requested that it evaluate whether chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) should be considered separately from other leukemias. That committee concluded that CLL could be considered separately and, on the basis of the epidemiologic literature and the etiology of the disease, placed CLL in the “sufficient” category. In response to a request from VA, the committee for Update 2008 affirmed that hairy-cell leukemia belonged in the category of sufficient evidence of an association with the related conditions CLL and chronic B-cell lymphomas.

Health Outcomes with Limited or Suggestive Evidence of an Association

In this category, the evidence must suggest an association between exposure to herbicides and the outcome considered, but the evidence can be limited by the inability to rule out chance, bias, or confounding confidently. The coherence of the full body of epidemiologic information, in light of biologic plausibility, is considered when the committee reaches a judgment about association for a given outcome. Because the VAO series has four herbicides and TCDD as agents of concern whose profiles of toxicity are not expected to be uniform, apparent inconsistencies can be expected among study populations that have experienced different exposures. Even for a single exposure, a spectrum of results would be expected, depending on the power of the studies and other design factors.

The committee responsible for VAO found limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to herbicides and three categories of cancer: respiratory cancer (after individual evaluations of laryngeal cancer and of cancers of the trachea, lung, or bronchus), prostate cancer, and multiple myeloma (MM). The Update 1996 committee added three health outcomes to the list: PCT, acute and subacute peripheral neuropathy (indicated as early-onset transient peripheral neuropathy after Update 2004 and then respecified as simply early-onset peripheral neuropathy after Update 2010), and spina bifida in children of veterans. Transient peripheral neuropathies had not been addressed in VAO, because they are not amenable to epidemiologic study. In response to a VA request, however, the

Update 1996 committee reviewed those neuropathies and based its determination on case histories. A combination of a 1995 analysis of birth defects among the offspring of veterans who served in Operation Ranch Hand and results of earlier studies of neural-tube defects in the children of Vietnam veterans (published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) led the Update 1996 committee to distinguish spina bifida from other reproductive outcomes and to place it in the “limited or suggestive evidence” category. No changes were made in this category in Update 1998.

After the publication of Update 1998, the committee responsible for Type 2 Diabetes, on the basis of its evaluation of newly available scientific evidence and the cumulative findings of research reviewed in previous VAO reports, concluded that there was limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant TCDD and type 2 diabetes (mellitus). The evidence reviewed in Update 2000 supported that finding.

The committee responsible for Update 2000 reviewed the material in earlier reports and the newly published literature and determined that there was limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant TCDD and AML in the children of Vietnam veterans. After release of Update 2000, researchers in one of the studies that it reviewed discovered an error in the published data. The committee for Update 2000 was reconvened to re-evaluate the previously reviewed and new literature regarding AML, and it produced Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, which reclassified AML in children from “limited or suggestive evidence of an association” to “inadequate or insufficient evidence to determine an association.”

After reviewing the data reviewed in previous VAO reports and recently published scientific literature, the committee responsible for Update 2006 determined that there was limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant TCDD and hypertension. AL amyloidosis was also moved to the category of “limited or suggestive evidence of an association” primarily on the basis of its close biologic relationship with MM.

With a bit more consistent epidemiologic data augmented by increased understanding of mechanisms arising from new toxicologic research, the committee for Update 2008 was able to resolve the Update 2006 committee’s lack of consensus and moved ischemic heart disease into this category, joining hypertension, another cardiovascular condition. New studies of Parkinson disease that yielded findings of an association with the specific herbicides of interest were deemed to move the evidence to the category of limited or suggestive.

Health Outcomes with Inadequate or Insufficient Evidence to Determine an Association

By default, any health outcome is in this category before enough reliable scientific data accumulate to promote it to the category of sufficient evidence or

limited or suggestive evidence of an association or to move it to the category of limited or suggestive evidence of no association. In this category, available studies may have inconsistent findings or be of insufficient quality or statistical power to support a conclusion regarding the presence of an association. Such studies might have failed to control for confounding or might have had inadequate assessment of exposure.

The cancers and other health effects so categorized in Update 2010 are listed in Table 1-1, but several health effects have been moved into or out of this category since the original VAO committee reviewed the evidence then available. Skin cancer was moved into this category in Update 1996 when inclusion of new evidence no longer supported its classification as a condition with limited or suggestive evidence of no association. Similarly, the Update 1998 committee moved urinary bladder cancer from the category of limited or suggestive evidence of no association to this category; although there was no evidence that exposure to herbicides or TCDD is related to urinary bladder cancer, newly available evidence weakened the evidence of no association. The committee for Update 2000 had partitioned AML in the offspring of Vietnam veterans from other childhood cancers and put it into the category of suggestive evidence; but a separate review, as reported in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, found errors in the published information and returned it to this category with other childhood cancers. In Update 2002, CLL was moved from this category to join Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the category of sufficient evidence of an association.

The committee responsible for Update 2006 removed several cancers (of the brain, stomach, colon, rectum, and pancreas) from the category of limited or suggestive evidence of no association into this category partly because of some changes in evidence since they were originally placed in the “no association” category but primarily because that committee had concerns about the lack of information on all five COIs and each of these cancers.

Health Outcomes with Limited or Suggestive Evidence of No Association

The original VAO committee defined this category for health outcomes for which several adequate studies covering the “full range of human exposure” were consistent in showing no association with exposure to herbicides at any concentration and had relatively narrow confidence intervals. A conclusion of “no association” is inevitably limited to the conditions, exposures, and observation periods covered by the available studies, and the possibility of a small increase in risk related to the magnitude of exposure studied can never be excluded. However, a change in classification from inadequate or insufficient evidence of an association to limited or suggestive evidence of no association would require new studies that correct for the methodologic problems of previous studies and that have samples large enough to limit the possible study results attributable to chance.

The original VAO committee found a sufficient number and variety of well-

designed studies to conclude that there was limited or suggestive evidence of no association between the exposures of interest and a small group of cancers: gastrointestinal tumors (colon, rectum, stomach, and pancreas), skin cancers, brain tumors, and urinary bladder cancer. The Update 1996 committee removed skin cancers and the Update 1998 committee removed urinary bladder cancer from this category because the evidence no longer supported a conclusion of no association. The Update 2002 committee concluded that there was adequate evidence to determine that spontaneous abortion is not associated with paternal exposure specifically to TCDD; the evidence on this outcome was deemed inadequate for drawing a conclusion about an association with maternal exposure to any of the COIs or with paternal exposure to any of the COIs other than TCDD. No changes in this category were made in Update 2000 or Update 2004. The Update 2006 committee removed brain cancer and several digestive cancers from this category because of concern that the overall paucity of information on picloram and cacodylic acid made it inappropriate for those outcomes to remain in this category. This left the finding of evidence of no association between paternal exposure to TCDD and spontaneous abortion as the sole entry in this category.

Determining Increased Risk in Vietnam Veterans

The second part of the committee’s charge is to determine, to the extent permitted by available scientific data, the increased risk of disease among people exposed to herbicides or the contaminant TCDD during service in Vietnam. Previous reports pointed out that most of the many health studies of Vietnam veterans were hampered by relatively poor measures of exposure to herbicides or TCDD and by other methodologic problems. Most of the evidence on which the findings regarding associations are based, therefore, comes from studies of people exposed to TCDD or herbicides in occupational and environmental settings rather than from studies of Vietnam veterans. The committees that produced VAO and the updates found that the body of evidence was sufficient for reaching conclusions about statistical associations between herbicide exposures and health outcomes but that the lack of adequate data on Vietnam veterans themselves complicated consideration of the second part of the charge.

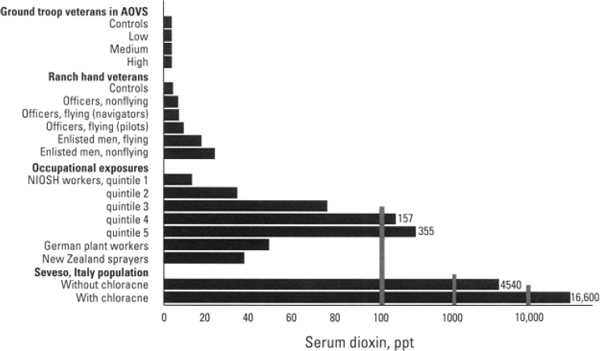

The evidence of herbicide exposure among various groups studied suggests that although some had documented high exposures (such as participants in Operation Ranch Hand and Army Chemical Corps personnel), most Vietnam veterans had lower exposures to herbicides and TCDD than did the subjects of many occupational and environmental studies (see Figure 1-1 from Pirkle et al., 1995). Individual veterans who had very high exposures to herbicides, however, could have risks approaching those described in the occupational and environmental studies.

Estimating the magnitude of risk of each particular health outcome among herbicide-exposed Vietnam veterans requires quantitative information about the

FIGURE 1-1 Comparison of TCDD exposures in various populations.

SOURCE: Pirkle et al., 2005.

dose–time–response relationship for the health outcome in humans, information on the extent of herbicide exposure among Vietnam veterans, and estimates of individual exposure. Committees responsible for VAO and the updates have concluded that in general it is impossible to quantify the risk to veterans posed by their exposure to herbicides in Vietnam. Statements to that effect were made for each health outcome in VAO (IOM, 1994) and in every update through Update 2004. The committee responsible for Update 2006 chose to eliminate the repetitive restatements in favor of the following general conclusion: “At least for the present, it is not possible to derive quantitative estimates of the increase in risk of various adverse health effects that Vietnam veterans may have experienced in association with exposure to the herbicides sprayed in Vietnam.” The committee responsible for later updates and the current committee have opted to retain the modification in the formatting of the health outcomes sections.

After decades of research, the challenge of estimating the magnitude of potential risk posed by exposure to the COIs remains intractable. The requisite information is still absent despite concerted efforts to reconstruct likely exposure by modeling on the basis of records of troop movements and spraying missions (Stellman and Stellman, 2003, 2004; Stellman et al., 2003a,b), to extrapolate from agricultural models of drift associated with spraying (Ginevan et al., 2009a; Teske et al., 2002), to measure serum TCDD in individual veterans (Kang et al., 2006; Michalek et al., 1995), and to model the pharmacokinetics of TCDD clearance (Aylward et al., 2005a,b; Cheng et al., 2006b; Emond et al., 2004, 2005, 2006). There is still uncertainty about the specific agents that may be responsible for a

particular health effect. Even if one accepts an individual veteran’s serum TCDD concentration as the optimal surrogate for overall exposure to Agent Orange and the other herbicide mixtures sprayed in Vietnam, not only is the measurement nontrivial but the hurdle of accounting for biologic clearance and extrapolating to the proper time frame remains. The committee therefore believes that it is very unlikely that additional information or more sophisticated methods are going to become available that would permit any sort of quantitative assessment of Vietnam veterans’ increased risks of particular adverse health outcomes attributable to exposure to the chemicals associated with herbicide spraying in Vietnam.

Existence of a Plausible Biologic Mechanism or Other Evidence of a Causal Relationship

Toxicologic data form the basis of the committee’s response to the third part of its charge—to determine whether there is a plausible biologic mechanism or other evidence of a causal relationship between herbicide exposure and a health effect. A separate chapter summarizes toxicologic findings on the chemicals of concern. In VAO and updates before Update 2008, a considerable amount of detail had been provided about individual newly published toxicology studies; the current committee concurs with the decision made by the previous two committees that it is more informative for the general reader to provide integrated toxicologic profiles for the COIs by interpreting the underlying experimental findings. When there are specific toxicologic findings pertinent to a particular health outcome, they are discussed in the chapter reviewing the epidemiologic literature on that condition. The current committee has continued the endeavor to refine this approach to make the chapter on toxicologic information more accessible to lay readers and more illuminating about its relevance to epidemiologic findings.

In VAO and updates before Update 2006, this topic has been discussed in the conclusions section for each health outcome after a statement of the committee’s judgment about the adequacy of the epidemiologic evidence of an association of that outcome with exposure to the COIs. As Update 2006 noted, the degree of biologic plausibility itself influences whether the committee perceives positive findings to be indicative of a pattern or the product of statistical fluctuations. To provide the reader with a more logical sequence, the committee responsible for Update 2006 placed the biologic-plausibility sections between the presentation of new epidemiologic evidence and the synthesis of all the evidence; this in turn led to the ultimate statement of the committee’s conclusion. The later committees have supported that change and have continued to arrange the sections in that fashion.

The remainder of this report is organized in 13 chapters. Chapter 2 briefly describes the considerations that guided the committee’s review and evaluation of

the scientific evidence. Chapter 3 addresses exposure-assessment issues. Chapter 4 summarizes the toxicology data on the effects of 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T and its contaminant TCDD, cacodylic acid, and picloram; the data contribute to the consideration of the biologic plausibility of health effects in human populations. Chapter 5 of Update 2010, which had two roles with respect to the epidemiologic information that constitutes the core of the committee’s deliberations has been separated into two chapters corresponding to those roles. First, the new Chapter 5 characterizes the relevant new epidemiologic literature published in this update period, indicating the study design, exposure measures, health outcomes reported on, and population studied. A new feature in this update is the placement of a summary of the finding of each health outcome chapter at its beginning. The second role is now addressed in Chapter 6, which provides a cumulative overview of the study populations that have generated findings (in some instances, in the form of dozens of separate publications) reviewed in the VAO report series. In addition to showing where the new literature fits into this compendium of publications on Vietnam veterans, occupational cohorts, environmentally exposed groups, and case-control study populations, it includes description and critical appraisal of the design, exposure assessment, and analysis approaches used.

The committee’s evaluation of the epidemiologic literature and its conclusions regarding associations between particular health outcomes that might be manifested long after exposure to the COIs are presented in the several chapters that follow. In Update 2010, three short-term responses presumptively associated with herbicide exposure (early-onset peripheral neuropathy, chloracne, and PCT) were moved from the body of the report to Appendix B because they develop shortly after exposure but are unlikely to arise for the first time decades after exposed people left Vietnam.

Chapter 7 addresses immunologic effects and discusses the reasons for what might be perceived as a discrepancy between a clear demonstration of immunotoxicity in animal studies and a paucity of epidemiologic studies that had such findings. Its placement reflects the committee’s belief that immunologic changes may constitute an intermediary mechanism in the generation of more distinct clinical conditions discussed in the following chapters. Chapter 8 discusses issues related to the possible overall carcinogenic potential of the COIs, particularly TCDD, and then assesses the available epidemiologic evidence on specific types of cancer, which are regarded as individual disease states that might be found to be service-related.

In this update, what had been one chapter on reproductive and developmental effects has been partitioned into two chapters. The first, Chapter 9, addresses reproductive problems that may have been manifested in the veterans themselves: reduced fertility, pregnancy loss, or gestational issues (low birth weight or preterm delivery). The second, Chapter 10, focuses on problems that might be manifested later in the lives of veterans’ children or even in later generations.

Chapter 11 addresses neurologic disorders. Chapter 12 deals with a set of conditions related to cardiovascular and metabolic effects. Chapter 13 now con-

tains the residual “other health outcomes”: respiratory disorders, gastrointestinal problems, thyroid homeostasis and other endocrine disorders, eye problems, and bone conditions.

A summary of the committee’s findings and its research recommendations are presented in Chapter 14.

Aylward LL, Brunet RC, Carrier G, Hays SM, Cushing CA, Needham LL, Patterson DG Jr, Gerthoux PM, Brambilla P, Mocarelli P. 2005a. Concentration-dependent TCDD elimination kinetics in humans: Toxicokinetic modeling for moderately to highly exposed adults from Seveso, Italy, and Vienna, Austria, and impact on dose estimates for the NIOSH cohort. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 15(1):51–65.

Aylward LL, Brunet RC, Starr TB, Carrier G, Delzell E, Cheng H, Beall C. 2005b. Exposure reconstruction for the TCDD-exposed NIOSH cohort using a concentration- and age-dependent model of elimination. Risk Analysis 25(4):945–956.

Cheng H, Aylward L, Beall C, Starr TB, Brunet RC, Carrier G, Delzell E. 2006b. TCDD exposure-response analysis and risk assessment. Risk Analysis 26(4):1059–1071.

Emond C, Birnbaum LS, DeVito MJ. 2004. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for developmental exposures to TCDD in the rat. Toxicological Sciences 80(1):115–133.

Emond C, Michalek JE, Birnbaum LS, DeVito MJ. 2005. Comparison of the use of physiologically based pharmacokinetic model and a classical pharmacokinetic model for dioxin exposure assessments. Environmental Health Perspectives 113(12):1666–1668.

Emond C, Birnbaum LS, DeVito MJ. 2006. Use of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for rats to study the influence of body fat mass and induction of CYP1A2 on the pharmacokinetics of TCDD. Environmental Health Perspectives 114(9):1394–1400.

Ginevan ME, Ross JH, Watkins DK. 2009a. Assessing exposure to allied ground troops in the Vietnam War: A comparison of AgDRIFT and Exposure Opportunity Index models. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology 19:187–200.

Hill AB. 1965. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 58:295–300.

IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). 1977. Some Fumigants, the Herbicides 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T, Chlorinated Dibenzodioxins and Miscellaneous Industrial Chemicals. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Man, Vol. 15. Lyon, France: World Health Organization, IARC.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1996. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 1996. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1999. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 1998. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2000. Veterans and Agent Orange: Herbicide/Dioxin Exposure and Type 2 Diabetes. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2000. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2002. Veterans and Agent Orange: Herbicide/Dioxin Exposure and Acute Myelogenous Leukemia in the Children of Vietnam Veterans. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

___________________

1Throughout this report, the same alphabetic indicator after year of publication is used consistently for a given reference when there are multiple citations by the same first author in a given year. The convention of assigning the alphabetic indicators in order of citation in a given chapter is not followed.

IOM. 2003. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2002. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2004. Veterans and Agent Orange: Length of Presumptive Period for Association Between Exposure and Respiratory Cancer. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2005a. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2004. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2005b. Gulf War and Health: Volume 3—Fuel, Combustion Products, and Propellants. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2006. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008. Improving the Presumptive Disability Decision-making Process for Veterans. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2008. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2010. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kang HK, Dalager NA, Needham LL, Patterson DG, Lees PSJ, Yates K, Matanoski GM. 2006. Health status of Army Chemical Corps Vietnam veterans who sprayed defoliant in Vietnam. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 49(11):875–884.

Michalek J, Wolfe W, Miner J, Papa T, Pirkle J. 1995. Indices of TCDD exposure and TCDD body burden in veterans of Operation Ranch Hand. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 5(2):209–223.

Pirkle JL, Sampson EJ, Needham LL, Pattterson DG, Ashley DL. 1995. Using biological monitoring to assess human exposure to priority toxicants. Environmental Health Perspectives 103(Suppl 3):45–48.

Stellman JM, Stellman SD. 2003. Contractor’s Final Report: Characterizing Exposure of Veterans to Agent Orange and Other Herbicides in Vietnam. Submitted to the National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine in fulfillment of Subcontract VA-5124-98-0019, June 30, 2003.

Stellman SD, Stellman JM. 2004. Exposure opportunity models for Agent Orange, dioxin, and other military herbicides used in Vietnam, 1961–1971. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 14(4):354–362.

Stellman J, Stellman S, Christians R, Weber T, Tomasallo C. 2003a. The extent and patterns of usage of Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam. Nature 422:681–687.

Stellman J, Stellman S, Weber T, Tomasallo C, Stellman A, Christian R Jr. 2003b. A geographic information system for characterizing exposure to Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam. Environmental Health Perspectives 111(3):321–328.

Teske ME, Bird SL, Esterly DM, Curbishley TB, Ray ST, Perry SG. 2002. AgDRIFT®: A model for estimating near-field spray drift from aerial applications. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 21(3):659–671.