to know more about what works at the community and societal levels. We also need to understand how evidence-based youth violence programs can be implemented and evaluated in other countries with varied resources and delivery systems. Related to this, we need to rigorously evaluate these adaptations to make sure they are working as intended within diverse contexts so that adolescents and emerging adults worldwide are healthy and fulfilling their potential.

II.4

CAN INTERVENTIONS REDUCE RECIDIVISM AND REVICTIMIZATION FOLLOWING ADULT INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE INCIDENTS?3

Christopher D. Maxwell, Ph.D.

Michigan State University

Amanda L. Robinson, Ph.D.

Cardiff University

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a complex social problem that can negatively influence the lives of both females and males throughout most of their lifespan.4 It is found in variable degrees in both developed and developing nations, in poor and rich milieus, and married and unmarried couples (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005). Although committed by both men and women against their intimate partners, this form of violence more often harms females, particularly those who are young (Sarkar, 2008) or have constrained resources (Adams et al., 2012). Females experiencing IPV report higher levels of depression than females in the general population, poorer mental and social functioning, and more frequent and adverse health issues (Bonomi et al., 2006, 2007). In addition, more so than any other type of crime, this form of violence poses unique challenges for public, private, and voluntary-sector agencies because the victim and offender are linked

_________________

3 We thank the workshop organizers and their sponsors for inviting us to present our research. Without the leadership and support of the National Institute of Justice, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the United Kingdom’s Home Office, as well as the support from several UK and U.S. foundations, most of the research we summarize in this report, including our own, would not exist.

4 The term Intimate Partner Violence describes physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse. See http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/definitions.html (accessed October 10, 2013).

through their shared intimacy, material resources, and legal, social, and familial relationships. For structured interventions to reduce this form of violence, pundits have argued for interventions that can address a range of issues that contribute to IPV, targeting not only those factors aligned with the offenders, but also the victims (e.g., Pence and Shepard, 1999; National Center for Injury Prevention Control, 2008). The purpose of this paper is to take stock of what we know now about interventions that may work to reduce repeat intimate partner violence. While there is a wide breadth of efforts to address IPV, particularly within Western developed countries, the scientific community is only now beginning to understand the limits and benefits of these efforts.

We structure this paper into two sections. To provide context, the first section describes several recent trends and patterns of IPV in the United States and the United Kingdom. The second section provides a synthesis of research that documents the impact that IPV-focused interventions have had on reducing repeat IPV. As we document throughout this paper, despite several decades of research activity on this topic, it is far from clear how to purposely reduce IPV recidivism and revictimization. Some early evidence produced by both quasi- and randomized experiments suggested that the rate of recidivism is lowered by both informal and formal interventions that produce consequences. However, more recent evidence produced by rigorous systematic reviews of other forms of interventions have suggested that these benefits are not as widespread as many had hoped.

What Are the Recent Trends and Patterns of IPV?

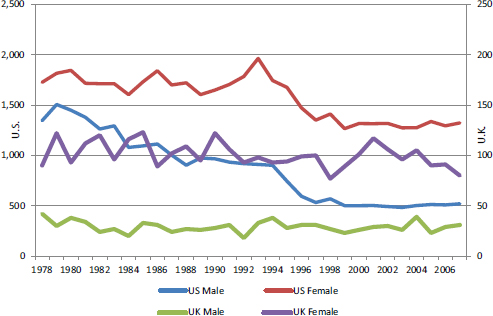

Figure II-1 displays 18 years of IPV self-reported victimization rates for the United States and the United Kingdom.5 As Figure II-1 illustrates, IPV rates are trending down in both countries. What we find particularly fascinating about this figure is that the two countries parallel each other both in terms of absolute rates of nonlethal violence and their downward trends. By 2010, the rates in both countries are less than four incidents per 1,000 residents. Both of these rates are also nearly 60 percent lower than in 1993.

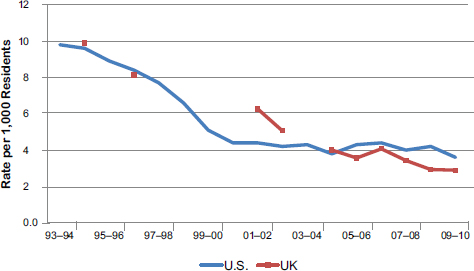

Figure II-2 displays the two countries’ IPV homicide counts by the victim’s sex. Similar to trends for nonlethal violence, the frequency of IPV

_________________

5 Data underlying Figures II-1, II-2, and II-3 were collected by national household victimization surveys (the National Crime Victimization Survey in the United States and the British Crime Survey in the United Kingdom) or from homicide incidents reported to the police that are annually aggregated by national statistical agencies. The primary summary data analyses were produced by staff at the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics and the United Kingdom Home Office. We extracted and combined the summary data from their published reports, from published data collections, and from more extensive tables produced by the staff for this report.

Figure II-1 U.S. and UK intimate partner violence victimization rates, 1993-2010. SOURCES: Christopher D. Maxwell and Amanda L. Robinson.

homicide incidents are also decreasing over time, particularly among U.S. males. Recently, researchers have reported or shown that IPV homicide rates are also decreasing in Canada and Australia (Dawson et al., 2009; Powers and Kaukinen, 2012; Sinha, 2012).

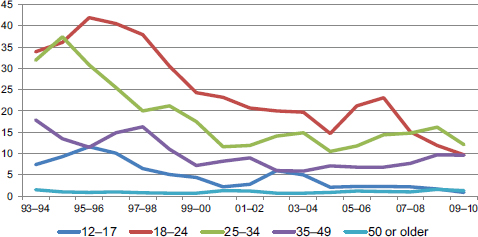

Figure II-3 displays IPV victimization rates by age group for the United States.6 As depicted in this figure, in the early 1990s the graph displays a fairly typical age by crime distribution curve (i.e., much higher rates among younger people that decline perceptively by age). Now, however, 15 to nearly 20 years later, the value of using age in explaining aggregate crime rates has dissipated by a factor of 3 or by about 75 percent. Accordingly, the decline in overall rates of IPV seems largely due to a drop in violence among those ages 18 to 35. The annual rates among older people have also have dropped, but not to the same degree as among younger adults.

At this point, it is important to recall what is known about the typical patterns of criminal offending over time. Criminological research has established that an individual’s rate of IPV—indeed any type of violent offending—decreases with the passage of time (Fagan, 1989; Feld and Straus, 1989; Quigley and Leonard, 1996; Whitaker et al., 2010). This has come to be known as natural desistance. This claim is supported by many IPV-focused studies that document a desistance rate from violence that is larger

_________________

6 Of course it is both possible and desirable to produce similar analyses using British Crime Survey data from the United Kingdom, which we are planning for a future publication.

than the recidivism rate even without formal intervention (Klein and Tobin, 2008). This latter point is important because the fact that violence decreases with time regardless of the presence or absence of an intervention means that to fairly test whether an intervention reduces violence one must have an equivalent control group to distinguish between natural and accelerated desistance. Therefore, the question about whether an intervention program works or not needs to be more explicitly phrased as “Does the intervention accelerate the rate of desistance among active IPV offenders and if so, to what degree?” In our attempt to answer this question, we primarily report the summary results from systematic, quantitative reviews of groups of similarly implemented RCTs. Unfortunately, this parameter does result in us reporting the results from a subgroup of available studies. However, as noted above, this is necessary for distinguishing between natural desistance and those accelerated significantly by an effective intervention.

What Impacts Have IPV-Focused Interventions Had on IPV?

In this section, we discuss the research evidence for different types of interventions that are intended to reduce IPV. For the purposes of this report, we focus on those interventions that are representative of the main U.S. and UK government approaches to the problem of IPV.

During the past two decades in particular, a broad platform of interventions has emerged that can be described as two parallel streams of intervention efforts: one focused on reducing IPV by targeting the offender and changing or controlling behavior, and the other focused on providing victims with resources that may reduce their risk of experiencing further victimization. In some instances, these interventions emerged organically whereas in other cases they resulted from systematic implementation efforts. Accordingly, combining the research evidence is not straightforward primarily because victims and offenders are not mirror opposites where interventions designed for one group always produce a known, consistent impact on the other.

Producing a clear statement of the impact of IPV interventions on IPV rates is further complicated by the fact that many interventions are now in place. These are located in different domains, including those delivered by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the voluntary sector, through the criminal justice system, or by health care providers. Each one of these systems will have dozens, if not hundreds, of interventions that have been designed and implemented in various ways across time and place. Then there are efforts to combine interventions (i.e., to deliver services to victims and/or offenders in multiagency partnerships) that might produce outcomes that are dependent on time, place, and fiscal challenges. In sum, although evidence clearly shows IPV rates are declining, another challenge is to state

which intervention or combination of interventions produced these very substantial reductions. Furthermore, we suspect it is likely that the path to desistance (for offenders) or to safety (for victims) will involve multiple exposures to multiple interventions over time.

Interventions Delivered by NGOs/The Voluntary Sector

We begin our review of intervention programs by focusing on the oldest, most well-established mechanisms to address IPV. These programs are commonly known in the United States and the United Kingdom as “refuges” or “battered women’s shelters.” Started in the 1960s, they emerged organically to address a stark gap in service provision. These settings establish a “safe space” for women (and more recently, men) fleeing their homes due to IPV. Thus, the setting alone constitutes an intervention, but other services are also delivered in these settings, such as legal and financial advice, counseling, and parenting and other skills programs.

The evidence to date about the benefits of this intervention is not promising when the assessment scientifically compares aggregate or summary rates rather than individual outcomes. Although there are no systematic reviews of shelter evaluations, nor a single RCT, there is one study that correlates shelter stays with IPV revictimization rates, but it did not produce positive, straightforward results (Berk et al., 1986). Several other studies using aggregated data have likewise not found a connection between more shelter resources and lower aggregated IPV rates (Farmer and Tiefenthaler, 1996; Dugan et al., 1999; Wells et al., 2010). However, because many types of interventions are delivered in shelter settings, identifying the specific mechanism that links to better outcomes for victims is difficult. Furthermore, these interventions may influence different outcomes across domains such as physical, psychological, sexual, and financial abuse; victims’ perceptions of safety and emotional well-being; and similar outcomes for their children. Consequently, services delivered in these settings—indeed the setting itself—continue to serve as the cornerstone in the response to IPV in the United States and the United Kingdom.

The next stage in the development of victim services was to offer support to women living in the community (i.e., women should not have to flee their homes to access services). Known as providing “advocacy,” these forms of interventions involve the provision of professional advice, support, and information to victims about the range and suitability of options to improve their safety and that of their children. A small body of rigorous research from the United States points to the benefits of providing support and advice to women in community-based settings (Sullivan and Davidson, 1991; Ellis et al., 1992; Jouriles et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2011). However, these studies are small, single-site evaluation designs that have not

consistently found that the intervention significantly reduces revictimization. We did locate one systematic review of 10 applicable RCTs. This review by Ramsay et al. (2009) concluded that intensive advocacy (12 or more hours in duration) might reduce physical abuse after the first year, but for no longer than 2 years, and that there are uncertain impacts on victims’ quality of life and mental health. However, evidence for one promising intervention entitled the Independent Domestic Violence Advisors (IDVAs) model was not yet available at the time of Ramsay et al.’s (2009) review. IDVAs are professional support workers who provide intensive support and safety planning with victims deemed to be at high risk of further abuse; IDVAs are now being used across the United Kingdom. A multisite pre-post study found improvements across a range of victim outcomes (Howarth et al., 2009), but the longer term impacts of this type of intervention have not yet been established (Robinson, 2009).

Criminal Justice–Based Interventions

We next turn our focus on responses by elements of the criminal justice system, particularly responses purposefully designed and implemented to reduce IPV. Perhaps the most notable example of such a response is the first randomized experiment that investigated the effect of a criminal sanction on any type of recidivism by offenders, commonly known as the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment (Sherman and Berk, 1984). This experiment compared arrest to two other traditional approaches used by the police (separation and mediation) to respond to IPV incidents. The authors found that arrest reduced the recidivism rate by half against the same victim within 6 months of the arrest. The National Institute of Justice then followed up on this study by sponsoring six “replications,” which became collectively known as the Spouse Assault Replication Program (SARP). By 1991, the five completed SARP studies had produced inconclusive and mixed outcome results (Garner et al., 1995); however, two later studies pooled together the replication studies, either by averaging their published findings or by merging and reanalyzing their raw case-level data. Both of these “meta-analyses” found that arrest was a significantly more effective policing intervention than informal responses (Sugarman and Boney-McCoy, 2000; Maxwell et al., 2002). Maxwell et al. (2002) reported that the victims whose abusers were randomly assigned to the arrest group reported significantly less frequent violence on average over the first follow-up year than those in the non-arrest, control group.

While the police are beneficial, they are just the first stage in the criminal justice process. Therefore, research that is more recent has focused on the decisions made by prosecutors and the judiciary, and on how these decisions influence the subsequent rate of repeat IPV. The most comprehensive

analysis to date reviewed 135 studies that produced data measuring the prosecution and conviction of IPV offenders. This study found that criminal charges were filed in about 60 percent of all arrests and that about 50 percent of IPV prosecutions resulted in a conviction (Garner and Maxwell, 2009). Thus, the authors concluded that the rates of prosecution and conviction for IPV were not, as was commonly reported, “rare” or “infrequent” occurrences. Maxwell and Garner (2012) subsequently reviewed in detail 32 of these 135 studies to assess whether more prosecution resulted in less recidivism. Their analysis showed that 65 percent of the 144 comparison tests produced no significant differences in the rates of recidivism among types of criminal sanctions; however, the authors argued that these studies were methodologically weak and thus unlikely to entirely separate the effect of the intervention from other factors, including selection biases. Research based on a more narrow focus on specialized domestic violence courts by Cissner et al. (2013) also reported mixed findings in terms of recidivism outcomes from nine quasi-experimental evaluations. Their report documents that 5 of the 12 data analyses produced significantly lower IPV recidivism rates among those cases processed by a specialized court. Among the other analyses, six produced results showing no difference in recidivism rates and one produced results indicating a significant increase in recidivism.

Besides criminal sanctions, courts can also compel offenders to participate in therapeutic treatment programs. These programs are loosely organized around the principles of the Duluth model, and thus they largely focus on promoting psychosocial or cognitive behavioral changes. The programs last from a few weeks to a year (Pence, 1983). Over the past three decades, 10 studies have tested various versions of this model, but none replicated another. Among these studies, four used an RCT design. A systematic review of these studies by Feder and Wilson (2005) reported that while the effect of treatment on reducing officially recorded recidivism was modest, the effect of treatment on reported revictimization was near zero. Among the six quasi-experimental studies, a positive correlation between length of treatment and the rate of recidivism was produced: the more treatment was attended, the less violence was reported during the first follow-up year. Unfortunately, these later studies were too weakly designed to produce unequivocal information about treatment effectiveness.

Finally, courts can also issue temporary and quasi-permanent restraining orders (ROs) when there are threats of or actual incidents of IPV. These orders are a form of civil sanctions because they all universally compel would-be offenders to not contact the complainant; augment existing punishment schedules if there is subsequent violence; and add sanctions for actions (or lack of actions) that are otherwise legal. Unfortunately, no one has yet completed a systematic review of studies that connect ROs to

recidivism or revictimization rates, nor has anyone fielded an RCT to test their efficacy. However, we were able to identify 21 individual studies that reported a relationship between the presence of an RO and IPV recidivism and/or revictimization. Although none of the studies employed an RCT design, 13 included a post-treatment comparison group, and another 4 used a pre-RO rate as their comparison group.7 Our codification of the results provides only mixed support for the use of ROs, as 43 comparison tests produced only 15 statistically significant results. The most prevalent finding is that there is no difference in the rates of recidivism or revictimization between those with and those without an RO.

Controlling IPV via Health Care Settings

We now turn our focus on interventions through health care settings; as the NGOs discussed earlier, these are places for victims to seek help that are not necessarily linked to the police or the courts. Interventions typically start when someone visits a health care provider, either in an emergency room (ER) or at their primary care provider, or someplace between them. Relative to many of the other areas we have assessed so far, the research on health care interventions is more rigorous. There are a number of RCTs and even more systematic reviews. In terms of screening victims, several published systematic reviews covering more than 30 studies find that screening instruments sufficiently and equally identify women experiencing IPV, and that there are no significant adverse effects on most women (Cole, 2000; Nelson et al., 2004; MacMillan et al., 2006). However, in terms of whether screening reduces morbidity, the evidence to date is not as positive. Neither of the two ER-based RCTs found significant, positive effects on IPV revictimization rates (MacMillan et al., 2009; Koziol-McLain et al., 2010), nor did the one primary care–based RCT study (Klevens et al., 2012). In addition, among the studies that examined outcomes after combining screening with another intervention, only one of six studies found significant reductions in IPV rates due to the interventions (Parker et al., 1999; McFarlane et al., 2000, 2006; Tiwari et al., 2005; El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Coker et al., 2012).

Multiagency Partnership Interventions

This final section discusses interventions that combine treatments from different domains. The first of these are programs that combine police and victim advocate interventions. These “teams” jointly visit a residence after

_________________

7 The 21 studies are listed at http://www.msu.edu/~cmaxwell/ROteststudies.html (accessed October 10, 2013).

an initial police response to provide services such as informing the victim of her rights, issuing an RO, warning the perpetrator, or providing transportation. These programs also represent what is likely the first known systematically planned and tested interventions to address repeat domestic violence incidents in the United States. The initial quasi-experiment was conducted in the late 1960s, and it found reduced rates of IPV homicides in the New York City neighborhoods with the program (Bard and Zacker, 1971).

Since these initial positive findings, this “team” approach had been implemented throughout the United States. More rigorous experiments also had been conducted to test their impact on subsequent violence. In 2008, Davis et al. (2008) produced a systematic review of 10 program evaluations. Among these evaluations, they identified five RCTs, which were all located in the United States. Across these five RCTs, this approach slightly increased the odds that a household reported another incident to the police, but did not significantly reduce revictimization. The authors concluded that “while these programs may increase victims’ confidence in the police … they do not reduce the likelihood of repeat violence.”

Regardless of these findings, many have argued that the police–advocacy partnerships only represent the tip of the iceberg in terms of what can be accomplished if far more collaborations are developed across all provider domains. Thus, over the past 25 years, various versions of community collaborations have been implemented across the United States and in the United Kingdom. While the early evaluations produced positive conclusions, none has yet used a controlled design. Furthermore, only one of the five most recent demonstration programs provided data on repeat victimizations or recidivism (Garner and Maxwell, 2008). This study found mixed evidence that two Community Collaborative Response (CCR) programs produced less violence than their comparison sites (Harrell et al., 2007). This finding is consistent with another 10-site evaluation of CCRs funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Post et al., 2010). This primary prevention study found that county-based CCRs do not significantly affect respondents’ knowledge, beliefs, or attitudes toward IPV; knowledge and use of available IPV services; nor risk of exposure to IPV.

In the United Kingdom, another approach called the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARACs) was piloted in Cardiff, Wales, in 2003. This program targets those victims deemed most at risk of escalating abuse or homicide. The program provides for a brief but focused information-sharing process involving representatives from the full spectrum of responding agencies, such as the police; health, housing, and social services agencies; and NGOs. MARACs are now in operation in more than 250 UK jurisdictions. An early process and outcome evaluation of the first MARAC showed that this program could provide an effective blueprint for how to help the most at-risk victims (Robinson and Tregidga, 2005;

Robinson, 2006). However, despite the proliferation of this model, the Home Office reports that Robinson’s study remains the only independent evaluation of their effectiveness (Steel et al., 2011).

Conclusion

In this brief paper, we have summarized the outcomes from a substantial body of research that tested whether intervention programs can reduce IPV recidivism or revictimization. We sought to document the outcomes of available systematic reviews, or individual studies within a particular domain if this was our only option. We have shown that there is proliferation of all types of IPV interventions across the United States and the United Kingdom, and that there are both single and multiagency approaches as well as victim- and offender-focused interventions. Yet, after about 45 years of producing systematic evidence, our knowledge about what accelerates the decline of IPV is still relatively weak. To date, while mindful of the methodological, ethical, and conceptual complexities that are involved, we are disappointed that only a small proportion of interventions had been subjected to rigorous RCT research protocols, or what is normally considered the “gold standard.” Nevertheless, there are a number of key points to take away from our summary.

First, IPV rates are declining significantly across the United States, the United Kingdom, and a number of other countries. Unfortunately, it is not possible to conclusively identify who or what program deserves the credit for producing this decrease. Our preferred interpretation of this finding is that better government and governance in the form of more investment, proactive responses, and the increased volume of services now available for victims and offenders is making a difference. This perspective is aligned with Pinker’s (2011, p. 121) claim that the recent “civilizing process” explains the drop of all sorts of violence across the globe over the past 20 years. Accordingly, the pronounced decline in IPV, particularly among the younger cohorts, could be optimistically interpreted as a consequence of the combination of specific and general deterrent effects produced by the multitude of interventions now in place.

Second, evidence in a number of areas is both rigorous and positive. For instance, to reduce IPV recidivism, the best available evidence suggests that a police response, particularly one that results in an arrest, is the most effective offender-focused solution. To reduce revictimization, advocacy programs combined with victim safety planning—particularly those delivered by NGOs in the voluntary sector—are linked to improvements across a range of victim outcomes. However, researchers have also demonstrated that neither approach is sufficient to address all incidents of intimate partner violence. Furthermore, no one has established how to link