Large Simple Trials Now and Looking Forward

KEY SPEAKER THEMES

Lauer

• The promise of large simple trials (LSTs) should not be discounted on the basis of their current limitations. History is riddled with disruptive innovations that displace older, less efficient technologies or approaches.

• LSTs and greater patient involvement in research will be key to moving the health care system to a future in which every clinical encounter is an opportunity for learning.

Horwitz

• LSTs pose a series of challenges and opportunities for the clinical research enterprise. These include solidification of their external validity, a better understanding of the implications of LSTs for the detection of treatment heterogeneity and patient safety, and exploration of opportunities for greater integration of patient-reported outcomes.

• Care must be taken to prevent LSTs from becoming large, complex trials. It will be important to preserve the efficiency of LSTs while their value for clinical decision making by physicians and patients is cemented.

The concept of large simple trials (LSTs) is not new, but the number of LSTs conducted is very small compared with the number of complex and often small clinical trials conducted each year. Although LSTs are uncommon, they have proven the effectiveness of treatments for common diseases, such as the early use of intravenous streptokinase during heart attacks and low-dose aspirin to reduce the risk of a first heart attack. They have also shown that some treatments are not effective, for example, that vitamin E does not prevent cancer.

Michael S. Lauer, director of the Division of Cardiovascular Sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, described his vision for the future of clinical research in which many simplified trials are carried out in regular care settings, making each clinical encounter an opportunity for learning. Ralph I. Horwitz, senior vice president for clinical sciences evaluation at GlaxoSmithKline, addressed the challenges as well as the opportunities posed by LSTs.

A VISION FOR LARGE SIMPLE TRIALS IN

THE LEARNING HEALTH SYSTEM

Michael S. Lauer gave a cautionary talk addressing those who might oppose the use of LSTs because the data routinely collected in electronic health records (EHRs) are inferior in detail and quality to data collected for traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs). He likened this view to that of Eastman Kodak of the first digital camera images. They were substantially inferior to film images, which made it easy for Kodak to dismiss the importance of digital camera technology.

Lauer thus began his talk by holding up an Instamatic camera, a popular film camera made by Kodak from the 1960s into the 1980s. He pointed to the year 1976, when Steven Sasson, a Kodak engineer, invented the digital camera, which has subsequently proceeded to eclipse the photographic film and film camera business almost completely. Although the technology was developed by Kodak, the company decided not to exploit its advantage and stuck to its film-based business model. After all, Kodak had 85 percent of the camera market and 90 percent of the film market in 1976. Although Kodak eventually produced digital cameras, the effort was too little, too late to halt the company’s decline. It filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2012. Lauer told the audience to remember the Kodak Instamatic before dismissing the LST model at its current stage of development.

Kodak’s failure to see that a new technology would destroy its business is not a unique case, Lauer noted. It is common for large organizations to have difficulty dealing with innovative technologies because they are suc-

cessful with their current business model, the new technology is usually initially inferior, and their established customers are not asking for it.

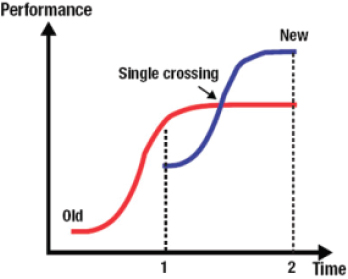

Lauer showed a figure from the work of Clayton Christensen, of Harvard Business School. Christensen coined the term “disruptive innovation” to describe the process in which a new product or service disregarded by established competitors is developed by others, becomes attractive to new customers at the bottom of the market, moves upmarket, and eventually outperforms the established technologies (see Figure 2-1) (Christensen, 1997). Lauer explained that over time, the performance of any given technology increases through incremental improvements made by competitors but eventually plateaus (the red line in Figure 2-1). At some point, the performance of a new technology developed by other organizations exceeds that of the older technology (where the blue line crosses the red line in Figure 2-1), rendering the older technology obsolete (blue and red lines at Time 2 in Figure 2-1).

Lauer then described the standard business model for RCTs, which he likened to the Kodak business model. Most RCTs involve a small number of subjects able to meet a narrow set of criteria and collect large amounts of very specific data on each subject. RCT recruitment and data collection, monitoring, and auditing processes are very costly; and often, RCTs can be supported only in academic medical centers. Moreover, given the relatively small sample sizes that they require, surrogate endpoints rather than clinical

FIGURE 2-1 Pathway of disruptive innovation over time.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Michael S. Lauer.

endpoints, which are often of more interest to patients and the clinicians caring for them, are often used.

What might a new model look like?, Lauer asked. He referred to GISSI (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico), a very large, very simple clinical trial conducted in Italy in 1984 and 1985 that proved that early thrombolytic treatment with streptokinase on in-hospital mortality of patients with acute myocardial infarction is efficacious (GISSI, 2013). The GISSI trial involved nearly 12,000 patients being treated in 176 coronary care units who were enrolled over 17 months at a cost of 30 euros per patient. Although GISSI was inexpensive and short, its findings had an enormous impact on clinical practice.

Other LSTs have been and are being conducted, although they constitute a small share of all clinical trials. Lauer described the Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (TASTE) trial, in which 5,000 patients in Scandinavia with acute myocardial infarction are being randomized to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the standard treatment, or to thrombus aspiration followed by PCI. Nearly all the data used for the TASTE trial have already been collected by existing registries. As a result, the trial is large enough to yield a meaningful outcome, yet the cost is very small compared with that of most trials.

Lauer identified greater patient involvement in their health care as another disruptive technology, especially in the area of rare diseases. As an example, he pointed to a trial of the efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), a progressive and often fatal cystic lung disease primarily affecting women. It was possible to conduct a trial for a disease that affects only 5 in 1 million women because a significant number of LAM patients were willing to participate in clinical trials through their organization, the LAM Foundation, to which many had already contributed clinical profiles.

Lauer proposed a new model that integrates trials into routine clinical care and that would involve the simultaneous conduct of many LSTs. They would enroll huge numbers of patients, which would enable robust estimates of treatment effects even among subgroups. However, the costs would be small because the research designs would be simple and existing data sources would be used. They would take place in general medical settings. The endpoints would be patient oriented with minimal or no adjudication. Theoretically, every patient could be enrolled in a clinical trial unless the patient has a disease that is already curable. Such LSTs would be an integral part of the learning health care system, because every clinical encounter would include an invitation to participate in a new clinical trial or a follow-up of an ongoing clinical trial.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES FOR LSTs

In his presentation, Ralph I. Horwitz laid out for the workshop participants the opportunities that LSTs could provide to improve clinical decision making by providers and by patients and the challenges to achieving this without turning LSTs into large complex trials. He posited that modern information technologies, such EHRs, could be harnessed to provide more detailed clinical data for LSTs without reducing the efficiencies of those LSTs.

He began by reviewing the case for LSTs, stating that trials of promising treatments with important but small to moderate treatment effects must have a very large number of participants to detect an effect with certainty. Because differences in the direction of treatment effects (positive or negative) are quite uncommon and differences in the magnitudes of treatment effects are likely to be equally distributed between groups, enrollment in an LST can be simple and therefore fast and cheap. Also, as LSTs are conducted in general medical settings with busy clinicians, the interventions need to be simple, which also means that they are more likely to achieve widespread adoption if they prove to be successful.

Horwitz said it was important to talk about what he called the “challentunities”—that is, the challenges and the opportunities—posed by LSTs. He identified four areas of “challentunities”:

1. Verification of the external validity of LSTs,

2. Treatment heterogeneity,

3. Patient safety, and

4. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

External Validity

LSTs, Horwitz said, are generally considered to have greater external validity than small RCTs with strict entry criteria, and therefore, their results are expected to be more applicable to the general patient population. A potential strength of LSTs compared with RCTs is their ability to detect small treatment effects that could confer substantial benefit when applied to an entire population. Therefore, the results of LSTs, even when they are strongly positive, are likely to have small impacts on individual patients.

Horwitz asked if it is possible that a very small benefit shown by an LST might have a negative benefit in the intended target population. He noted that LSTs, like all clinical trials, have selection criteria, and therefore, it is possible that patients meeting those criteria may have a response different from that of the overall target population. For example, he said, in the GISSI trial cited by Michael S. Lauer, only 45 percent of the 43,000 patients admitted to the coronary care units of the participating hospitals

were randomized in the trial. The others had clinical characteristics that made them ineligible. Because the absolute risk reduction shown by the GISSI intervention was just 1.4 percent and the mortality rate of the excluded patients was quite different (about double), it is possible that the intervention might have a negative effect on the general population that was not detected in the trial.

Horwitz suggested that the proponents of LSTs need to address whether the application of the results of LSTs to the entire target population will, in fact, achieve the benefits observed in the design of the original study. It is not a reason not to do these trials, he said, but it is a reason to think hard about the effects on individual patients and whether the net benefit for the population is that which is intended.

Treatment Heterogeneity

Treatment heterogeneity refers to the different degrees of impact that an intervention might have on subgroups within the population, such as those with certain comorbid conditions. An assumption made in LSTs, Horwitz said, is that treatment heterogeneity is unlikely to be a major problem. Although effects may differ between subgroups, they are likely to be in the same direction (positive or negative) and not qualitatively different enough to be of practical concern. This allows LSTs to avoid collecting detailed information on each participant, an important advantage in terms of the cost and the complexity of conducting LSTs.

However, an understanding of treatment heterogeneity can be very valuable in clinical trials. Horwitz asked if it is possible to validly and efficiently look at treatment heterogeneity by collecting the relevant clinical and laboratory data within an LST. He predicted that a recurring topic of the workshop would be the extent to which EHRs, as they are currently constituted, could provide data for subgroup analyses easily and cheaply and how the future development of EHRs could better enable this.

Patient Safety

Horwitz asserted that ensuring the safety as well as the effectiveness of medicines is a fundamental, critical requirement in the preapproval period for all new medicines and increasingly in the postapproval period. Well-tested procedures for assessing the safety risk in new medicines exist. When adverse events occur with any new medicine, detailed data on the clinical context in which the adverse event occurred are required for regulatory review and approval. Horwitz noted that it can be frustrating to rely on data collected for other purposes to identify the antecedent events associated with an adverse event when the relevant data were not systematically

collected as part of the original data collection process. He noted that it will be important to determine how to suitably assess the safety of medicines and devices through streamlined approaches such as LSTs, if they are to be used for those purposes.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

PROs, such as measures of morbidity or quality of life, are becoming an important part of clinical trials, but they are not well captured by the usual standardized measures used in RCTs. Horwitz suggested that LSTs might be an opportunity to better incorporate PROs into systematic assessments, expanding the value of LSTs for patients and physicians. He was optimistic that new information technologies will assist with the collection of data from and about patients without reductions in the efficiencies of LSTs.

Conclusion

Horwitz concluded by warning against turning LSTs into large complex trials. The question before the workshop participants, he continued, was how to preserve the efficiency of those trials while increasing their value for clinical decision making by physicians and patients. He noted that one way will be to use information technology to design and conduct LSTs. They can then be conducted without requiring patients to travel to brick-and-mortar research facilities by using electronic information technology systems for recruitment, informed consent, medication orders, and follow-up. Horwitz mentioned that a group called Mytrus is trying to pioneer such approaches and that social media like PatientsLikeMe could be used to obtain PROs.

Christensen, C. 1997. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

GISSI (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico). 2013. What Is Gissi? http://www.gissi.org/EngIntro/T_Intro_ENG.php (accessed June 17, 2013).

This page intentionally left blank.