Emerging Understandings of Group-Related Characteristics

In the military, as in most other modern organizations, little work is done by individuals working alone. Thus it is important to be able to assess individuals not only on the basis of their individual performance potential but also on the basis of how their characteristics might operate in a group setting. During the second day of the workshop, the third panel, Group Composition Processes and Performance, was devoted specifically to issues related to assessments that can provide insights into group performance and the effective assembly of groups. Invited presentations from Anita Williams Woolley, Scott Tannenbaum, and Leslie DeChurch included discussion of the “collective intelligence” of a team, how to assess and predict team performance, and how best to assemble teams.

To begin her presentation, Anita Williams Woolley, an assistant professor of organizational behavior and theory from Carnegie Mellon University, described various types of animals that exhibit “collective intelligence”—memory or problem-solving behaviors that are the product of an interaction among members of the group rather than simply a reflection of the capabilities of the individual members. Ant colonies, Woolley said, provide one of the best examples in that individual ants are simple creatures with little memory or problem-solving ability, but collectively they exhibit impressive behavior. They create complex structures, for

example, and they locate sources of food and assign collection priority according to distance from the nest.

After these introductory observations, Woolley described her research on collective intelligence in groups of people. She began her research program with two specific questions: (1) Is there evidence that groups of people have some form of collective intelligence—a product of collaboration within the group that goes beyond what the group’s members can accomplish individually? (2) If collective intelligence exists, is it something that transcends domains—that is, if a group excels in one area or on one type of task, is it likely to excel in other areas or on other tasks? Her research shows that the answer to both questions is a clear “Yes” (Woolley et al., 2010).

Collective intelligence, Woolley explained, can be thought of as a group version of the general intelligence factor, g, for individuals. The existence of g, which was originally hypothesized by Charles Spearman (1904) in the early part of the 20th century, can be inferred from the fact that people who do well on one type of task also tend to do well on other types of tasks (Deary, 2000). The idea behind g, Woolley said, is that it is a capability that is not specific to a particular domain but rather one that transcends domains. Similarly, if it could be shown that groups that do well on one type of task also tend to do well on other types of tasks, then one could infer the existence of a collective intelligence, c, associated with groups. Woolley and her colleagues initiated a research program to investigate this hypothesis.

In particular, Woolley said, there were several specific questions that she sought to answer with her research:

- Is there evidence of a general collective intelligence (c) in groups?

- Can we isolate a small set of tasks that is predictive of group performance on a broader range of more complex tasks?

- Does c have predictive validity beyond the individual intelligence of group members?

- How can we use this information to build a better science of groups?

Woolley hoped it might be possible to develop tests for collective intelligence in groups that played a role similar to intelligence quotient (IQ) tests for individuals—that is, tests that sample from a relatively small number of domains but that generalize to a broader set of domains and thus could provide a relatively convenient way of predicting the likely performance of groups on a large variety of tasks.

Woolley’s first study to investigate the possible existence of a collective intelligence involved 40 groups that each spent five or more hours in her lab (Woolley et al., 2010). After a group’s members were assessed on

individual intelligence and a number of other characteristics, the group worked together on a range of tasks and also, after the tasks, on a video game simulation to provide a collective measurement of performance.

The tasks were divided into four types: (1) generating tasks, which consisted of such things as brainstorming sessions and which benefited from a variety of inputs so as to devise more creative solutions; (2) choosing tasks, typical decision-making tasks in which the group needed to identify the individual who had the right answer to a question; (3) negotiating tasks, which involved trading off against competing interests to come up with a solution that best suited the group as a whole; and (4) executing tasks, which required careful coordination of inputs to accomplish goals quickly and accurately. Each type of task required a fundamentally different approach for the group to perform at a high level, Woolley explained, so there was no obvious reason to assume that a group that was good at one task, such as brainstorming, would also be good at another task, such as figuring out which group member knew the right answer for a decision-making task.

Nonetheless, analysis of the data from the 40 groups found a clear correlation between performances on different tasks, Woolley reported, such that a group that did well on one task type was more likely to do well on another. “We also had a first-principle component that accounted for 43 percent of the variance,” Woolley said, “which compares favorably to IQ tests, where the first component generally accounts for between 30 and 50 percent of the variance.” When they carried out a confirmatory factor analysis on the data, they found clear evidence that a single factor explained the relationships among the tasks better than a multifactor solution, and, furthermore, that a single general factor of collective intelligence was also a strong predictor of how the groups performed later on the criterion task (Woolley et al., 2010). Most importantly, Woolley emphasized, the collective intelligence factor did a far better job of predicting performance on the video game simulation than did the IQ of the individual group members. “We modeled this in terms of the maximum IQ score, the average IQ score, et cetera,” Woolley said, “and it didn’t really add any explanatory value to our model.” Later she repeated the study with a larger sample, a broader range of group sizes, and a different criterion task, and she found very similar results: The collective group intelligence, as determined from the range of tasks, was much more predictive of performance on the criterion task than the IQ scores of the individual group members (Woolley et al., 2010).

In later studies she investigated how well collective intelligence predicted group learning (Aggarwal et al., unpublished). It is well known that individual intelligence predicts learning, she noted. “So we were interested to see whether this would be true at the group level as well.”

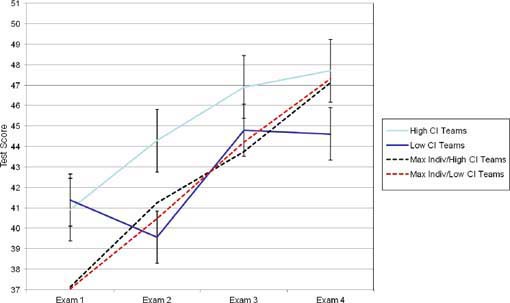

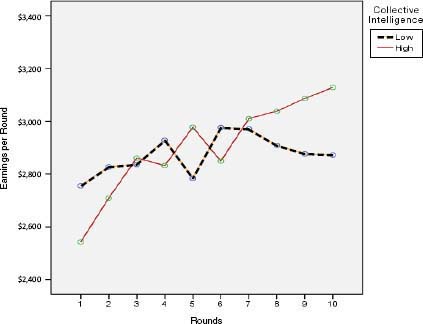

To test this idea, Woolley assembled about 100 teams to study. After administering the collective intelligence tests to each of the teams, the teams played a number of rounds of a behavioral economics game in which the goal is to earn as much money as possible. After each round, the team received feedback about how much money it had earned. As shown in Figure 4-1, on average, the groups with low collective intelligence improved very little through 10 rounds of the game, while the groups with high collective intelligence improved greatly in terms of the amount of money they earned.

Additionally, Woolley and her colleagues looked at teams of students in a Master’s program in business administration, who work together on projects over the course of a term (Aggarwal et al., unpublished). The students took four different exams as a team, with the individual members first taking each exam individually and then repeating the same exam with their group, without first receiving feedback on their individual performances (the dashed lines in Figure 4-2 illustrate the highest individual score obtained in each team). The teams with low collective intelligence and those with high collective intelligence scored almost equivalently on the first group exam. However, as the solid lines in Figure 4-2 illustrate, while teams with either high or low collective intelligence improved,

FIGURE 4-1 Collective intelligence and learning as measured in a behavioral economics game.

SOURCE: Adapted from Aggarwal et al. (unpublished).

by the fourth group exam, the teams with high collective intelligence improved significantly more and outscored the teams with low collective intelligence. Woolley noted that, when the group scores (solid lines in Figure 4-2) were compared with the highest individual score on each team (dashed lines in Figure 4-2), the teams with low collective intelligence scored no better than their best team member 50 percent of the time, while the teams with high collective intelligence consistently scored significantly better than their best team member.

Since the collective intelligence of these teams depends on more than the intelligence of their individual members, Woolley said, the question is what factors influence collective intelligence. Or, in other words, what are the best predictors of collective intelligence?

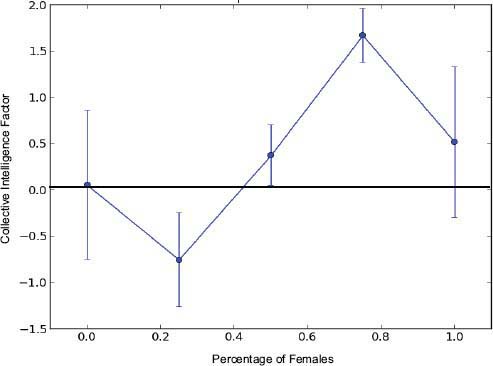

“We’ve administered a variety of measures of group climate, things like group satisfaction, cohesion, or motivation, and have not found any significant relationships [with collective intelligence],” Woolley said. “We’ve administered a variety of personality measures, largely based on the Big Five [personality traits], … and we haven’t found consistent relationships with personality.” However, she said, one predictor of collective intelligence that has emerged repeatedly in her studies is the proportion of females in the group. Judging from data collected from other studies, the relationship is a curvilinear one (see Figure 4-3). Groups with a low percentage of women tend to show lower collective intelligence than groups consisting solely of men. Whereas groups with more than about 20 percent females in the group up to about 75 to 80 percent female display increasing collective intelligence. The trend reverses above 80 percent females and collective intelligence drops slightly as the percentage approaches 100.

This trend is consistent with research done by Myaskovsky and colleagues (2005), Woolley said. What they found, Woolley explained, is that in groups with just one female, you often don’t hear much from them. Whereas in groups with only one male, you actually hear a lot from the women, so the amount of communication overall in the groups that are predominately female is much greater than in groups that are predominantly male (Myaskovsky et al., 2005).

A second factor that is predictive of collective intelligence, Woolley noted, is the social perceptiveness of the group’s members. This can be measured with a simple test that asks the test taker to select one of four options that best describes the mental state of a person shown in a photograph, but limited to only showing the person’s eyes. People who are more socially perceptive are more accurate in inferring mental states from these narrow-view photographs (Baren-Cohen et al., 2001). Woolley found that groups whose members have a higher average score on social perceptiveness also tend to have higher collective intelligence. Because women

FIGURE 4-3 Relationship between collective intelligence and the percentage of females in the group.

SOURCE: Adapted from Engel et al. (unpublished).

tend to score higher on social perceptiveness, having more women in a group will generally raise its average social perceptiveness score, Woolley said, which explains most, but not all of the effects associated with the proportion of women in the group.

By studying communication in these groups, Woolley has also found that uneven distribution in speaking turns is negatively correlated with collective intelligence, so groups in which one person dominates the conversation tend to have lower collective intelligence (Woolley et al., 2010). “We found it was true even for online groups that were communicating by chat only,” she said (Engel et al., unpublished).

She has also examined the effects of cognitive diversity on collective intelligence. There are various cognitive styles, she noted. Some people are verbalizers, while others are visualizers. Among visualizers, some are better with objects, while others are better with spatial patterns. When she examined the relationship between diversity of cognitive styles and collective intelligence, Woolley found a curvilinear pattern: Collective intelligence tends to increase as the cognitive diversity of a group increases,

but only up to a point; once a group gets too cognitively diverse, its collective intelligence tends to drop. Groups that are highly diverse in cognitive styles tend to experience difficulty communicating and arriving at agreement on strategies to deal with different problems because they are fundamentally different in the way they think and approach a task (Aggarwal and Woolley, 2013).

Looking ahead, Woolley said, she is interested in discovering what else predicts collective intelligence. She has also been working to refine her battery of tests so that it can be used in other environments to predict team performance and also so that it can be used to experiment with tools that enhance various processes that improve collective intelligence.

Discussion: Collective Intelligence in Online Groups

In the discussion period following her presentation, Woolley noted that she had recently finished a study comparing face-to-face teams with online teams and found that the pattern of relationships still held. “Surprisingly,” she said, “the proportion of women is even more influential in the online teams than in the face-to-face teams, even when they are anonymous and they don’t necessarily know that the other people are male or female.”

Gender information is not provided explicitly to online team members, but, Woolley noted, the team members assign themselves chat names, which may or may not indicate their sex. If a team member assigned herself a name that is clearly feminine, she said, then other team members could guess that she was a woman.

Committee member Randall Engle commented that Woolley’s results indicate that the collective intelligence of the group is dependent on the number of females in the group, even when the group members themselves do not know how many females are in the group. This raises the possibility, he observed, of doing some interesting experiments in which the team members’ perceptions of their teammates could be manipulated to study, for instance, whether the belief that the team was mostly male or mostly female might make a difference to performance.

Woolley responded that she has some collaborators who have been manipulating perceptions of cultural background rather than of gender, so that while everyone in the group is American, the group members are led to believe that some of their teammates are Arabs. They have found that such perceptions do indeed affect the group’s collective intelligence.

Furthermore, Woolley said, social perceptiveness is even more influential in the online teams than in the face-to-face teams. Rodney Lowman, who led the discussion on ethical implications at the end of the workshop’s first day, pointed out that while Woolley described measuring

social perceptiveness in the lab with visual tests that ask a subject to determine a person’s emotional state from looking at a picture of the person’s eyes, people have no such visual data to work with online. “That’s correct,” Woolley responded, adding that conceptually this measure of social perceptiveness is tapping into “theory of mind”: the ability to represent to oneself another person’s mental states based on subtle cues. “What it suggests,” Woolley noted, “is that the measure generalizes to other modes than simply the visual identification of emotional expression.”

To a certain degree, well-qualified individuals are more likely to perform well as a team on various tasks, relative to a team of less-qualified individuals. However, as Woolley’s work on collective intelligence found, individual characteristics tell only part of the story (Woolley et al., 2010). Other factors also play a role in team effectiveness. The question, then, is what those factors are and how to predict the effectiveness of a team from the characteristics of its individual members. Scott Tannenbaum, president and cofounder of The Group for Organizational Effectiveness, Inc., discussed this issue in his presentation on team composition.

Modeling Team Composition

Tannenbaum began with a discussion of theoretical considerations. Noting that there are many different approaches to putting together an effective team, he described a simple classification system as a way of imposing some order on the variety of approaches. In his system, there are four types of team composition models (see Table 4-1).

The first and most traditional model, represented by the upper left quadrant in Table 4-1, is the individual selection model, in which individuals are assessed in various ways and then matched to a job. “One way you could think about this,” Tannenbaum said, “is that this is about picking individuals who are most qualified to do [a specific] job.”

It is also possible to consider individual characteristics that are related to the functioning of a team—that is, characteristics that make a person a good team player. A personnel model with teamwork considerations (upper right quadrant in Table 4-1), Tannenbaum said, seeks to select people based not only on their individual competencies but also on how well they are likely to collaborate and coordinate when working as part of a team. There are many different types of team competencies, Tannenbaum explained, and some of them are generic, meaning that, regardless of what team a person is on and what sorts of tasks the person is asked to do, these competences will help the person be a better team player. For

TABLE 4-1 Four Models of Team Composition Effectiveness

| Individual Focus | Team Focus | |

| Individual Models | Traditional Personnel—Position Fit Model Position-Specific KSAOs Cognitive Ability Psychomotor Ability Conscientiousness |

Personnel Model with Teamwork Considerations Team Generic KSAOs Organizing Skills Cooperativeness Team Orientation |

| Team Models |

Relative Contribution Model Relative KSAOs Weakest Member Highest Leader Propensity Cooperativeness of Most Central Person |

Team Profile Model KSAOs Distributions Average Experience Functional Diversity Team Requisite KSAOs |

NOTE: KSAOs = knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Mathieu et al. (2013).

example, this might include communications skills, organizational skills, cooperativeness, and team orientation.

These first two types of models are relatively well studied and well accepted, Tannenbaum said; the remaining two types of models are where he expects many future developments. These models approach team composition from the team perspective, rather than from the individual perspective. “This is about thinking about a team member’s talent,” Tannenbaum said, “but you can’t look at it in isolation. It is relative to other people on the team.”

For example, consider a team of people working an assembly line. The person with the poorest skills in a particular area will limit the overall team performance. In other cases, the key factor in team performance might be the most positive person or the strongest person, or it might be the level of cooperativeness displayed by the person who is most central to the team’s workings. This relative contribution model, represented by the lower left quadrant in Table 4-1, assesses individual characteristics in a team framework.

The most complex model, represented by the lower right quadrant of the table, is the team profile model, which seeks to optimize the blend, synergy, and profiles of the team members. “You take a look at all these pieces simultaneously,” Tannenbaum said, and consider the team’s collection of skills. So, for example, in some instances it may not matter exactly who performs specific tasks, only that at least one person on the team has the requisite skill and that collectively the team possesses the necessary skills to fulfill the team’s mission. It is the overall team profile that matters.

As an aside, Tannenbaum noted that he and his colleagues have been working to create mathematical models that describe the effectiveness of teams under each of these models. The idea, he said, is to show that it is possible to describe these team characteristics with algorithms and not simply in words.

The Team Role Experiences and Orientation Assessment

With this theoretical grounding in place, Tannenbaum described the Team Role Experiences and Orientation (TREO) assessment. “TREO is a measure of team role propensities,” he explained. “In other words, in team settings, what is someone likely to do? What do they gravitate toward?” TREO is based on the premise that by understanding people’s team-related preferences and interests—what they like to do and what they are interested in when on a team—and by learning about their past behaviors when they were on previous teams, it is possible to predict how they are likely to behave on teams in the future (Mathieu et al., unpublished). With that information in hand, it should be possible to examine the propensities of the different team members to predict the performance of that team more accurately than would be possible simply from knowing about the knowledge, skills, and abilities of the individual team members.

TREO is a 48-item self-assessment that scores people against six roles: organizer, challenger, team builder, doer, innovator, and connector. “These are just what they sound like,” Tannenbaum said. “Organizers are people who tend to structure and provide guidance and control over things. Challengers are people who are likely to speak up and question things. Innovators are folks who have new ideas to bring to the table.” The doers are “head-down people that will get the work done,” while team builders “focus on the morale and engagement of the team,” and connectors build bridges with people outside the team.

Using seven different samples, Tannenbaum and his team conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to test the validity and reliability of the TREO constructs, and the results are promising, he reported. They also compared the TREO characteristics with the usual Big Five personality traits and found that, while there are some logical correlations, the TREO characteristics generally do not overlap with the standard personality traits. Tannenbaum said that this makes sense because the Big Five are intended to measure individual personality, while TREO is looking at how people act when they are in team settings. He added, “this is back to some of that contextualization that people were talking about yesterday”—that is, one way to improve assessments is to take context into account instead of simply working with context-free assessments such as the Big Five personality traits.

Tannenbaum and his team have compared the TREO results with measures of teamwork knowledge and with peer assessments, in which they asked team members about the behaviors they had observed in other members. The peer assessments exhibited patterns similar to what TREO indicated, demonstrating a correlation between what people self-reported on the TREO assessment and what others reported about the behaviors they saw exhibited by team members.

At first, Tannenbaum said, it might seem as if the TREO assessment belongs in the upper right quadrant of Table 4-1 because the scores seem to be about individuals and their team-related characteristics. But TREO is better thought of as falling in the bottom half of the figure, he added, where the team composition and profile are emphasized. Imagine, for example, that a TREO assessment of a five-person team indicates that all members score very high on organizing or on challenging; that would be very revealing about the way the team was likely to function—or not function. “Here’s where the bang for the buck is, in terms of being able to move things forward,” he said.

Although he has done only a few studies testing whether TREO can predict team performance, Tannenbaum views the preliminary data as promising. He briefly described results from three studies, one that looked at 45 Army transition teams and two that used student samples—one with 110 teams doing a simulated aviation task and the other with student teams that worked together over a 10-week period on a variety of tasks (Tannenbaum et al., 2010).

In the student team studies, the students were first tested on individual knowledge, skills, and abilities and then a team profile was created. In one study, the team profile was created using TREO results, and in the other the profile was constructed using personality measures. In both cases, adding the team profile details increased predictive power. In particular, the team profiles were used to predict the effectiveness of various team processes, which the literature shows do a very good job of predicting team performance (Tannenbaum et al., 2010). Adding the team profiles to the information about individual abilities produced better predictions of team processes than information about individual abilities alone, Tannenbaum said. “So the punch line here is that team composite data can account for additional variance above and beyond just looking at individuals.”

The results from the study with Army transition teams were somewhat more complex. The teams consisted of soldiers who were together for approximately 16 weeks before they were deployed. “What we found was a compensatory relationship,” Tannenbaum said. If a team was low on some individual capabilities but higher on the team profile, the better team profile could make up for some of the lack of individual capabilities. But teams that were low in both areas performed poorly. “So it’s not always so

straightforward, but yet again there’s a relationship showing that we can predict team processes above and beyond that of individual performance” by looking at team composite data in addition to individual data.

As several participants noted, the ultimate goal of developing an understanding of team performance is to be able to improve team assembly—to put together individuals on teams in a way that maximizes performance. Both Tannenbaum and Leslie DeChurch, an associate professor of organizational psychology at Georgia Institute of Technology, addressed this challenge.

Team Composition System

Tannenbaum described a tool that he and his team developed at The Group for Organizational Effectiveness, Inc., to aid in assembling a team. The tool, called the Team Composition System (TCS), is still in the prototype stage, but Tannenbaum described it to illustrate possible approaches for improving team assembly.

The underlying impetus for developing TCS, he said, was to address the challenge of assembling a team while considering so many different factors that a person could not effectively keep track of them all without help. As examples of the many potentially relevant factors, Tannenbaum cited the knowledge, skills, and abilities of the various candidates; their personality traits and how people will fit together; which abilities are needed on the team; who the weakest link is likely to be for a particular task, and so on. TCS includes the mathematical formulas previously developed to describe the effectiveness of a team in terms of various individual and team characteristics; it also includes input from the TREO assessment. Currently, Tannenbaum said, TCS is designed to build only one team at a time. Optimizing the assembly of multiple teams from a group of candidates requires consideration of so many different possible permutations that it was not practical with the computing power available to him.

Tannenbaum explained that TCS takes a decision maker through a series of six steps:

- Describe the team.

- Specify the team requirements.

- Manage candidate data.

- Run the analysis.

- Review the results.

- Lock in candidates, adjust assumptions, re-run the analysis, decide.

He reiterated that TCS is designed as a decision aid, not a decision maker. It helps guide someone through assembling a team by offering analyses of different potential teams. It shows configurations that are predicted to be most effective based on the assumptions provided, but it does not make the decision for the decision maker. “You can go back, change your assumptions, lock in people, unlock people. This is how decision makers tell us they operate. They don’t want a system telling them the answer. They want a system that they can use to have data to help make decisions.”

TCS has a number of additional features that increase its flexibility to adjust to the user’s needs. For example, it allows users to specify team characteristics in various ways. Depending on the task, some positions on a team may be more important than others; therefore, the system allows positions that are more central to be weighted more in the analysis.

Sometimes there are skill requirements that need to reside in the team but not in an individual position. Tannenbaum offered an example: “I need somebody on the team who speaks Farsi. It doesn’t have to be the commander, it doesn’t have to be the navigator, but it has to be somebody.” Or it might be that a certain number of NATO partners are needed on the team. The system can steadily maintain that requirement while other factors are manipulated. Various other types of constraints can be included as well. Sometimes two people can’t work together, for instance. The system can be told to ignore any potential team options with those two individuals as members of the same team.

After all the data are entered, including such things as the TREO assessments of potential team members, the system runs an analysis of all possible team combinations and, based on the various assumptions and constraints that were entered, it identifies the five potential team configurations with the highest predicted team effectiveness scores. It also provides alerts that signal potential problems with each team. It can identify potential weak links, for example, based on individual position readiness scores. Or it might note that more than half the team scores high on the “challenger” scale, which may indicate team members might spend too much time critiquing one another. TCS, as Tannenbaum explained, monitors and manipulates many more factors than any individual could, so it can make the team assembly process more effective and efficient.

Mechanisms and Modalities in Assembling a Team

In her presentation, Leslie DeChurch described a different way of thinking about team assembly. She began by arguing that the current approaches to understanding team effectiveness do not work particularly well. “Over the last 13 years there have been 8 meta-analyses that

have desperately looked for significant effect sizes linking team composition, diversity, and capabilities to team performance,” she said (see, for example, Stewart, 2006, and Bell et al., 2011). “And basically we don’t really know much despite the search for moderator after moderator. The best-case scenario is, we know that if you put smart people on a team [the team tends] to perform better.”

There are three important deficiencies in this literature, according to DeChurch. First, the examination of team composition has been too narrow. “We need instead to talk about team assembly,” she said. That is, it is not enough to examine the characteristics of the individuals on a team; one must also take into account how the team was put together.

“The second thing,” she said, “is that if we want to understand how individual characteristics combine toward collective capability, we have to model the mechanisms. Teams are about relationships.” Thus, DeChurch emphasized, it is crucial to examine how people work together—or do not work together—on a team.

Third, DeChurch believes the best effects of individual characteristics on the construction of team capabilities will emerge if one looks at the dyadic or the relational level of analysis. Teams consist of many people, but relationships are generally one on one, and thus, she explained, dyads should be the basic unit of analysis when understanding why some groups work better than others.

Team Assembly Mechanisms

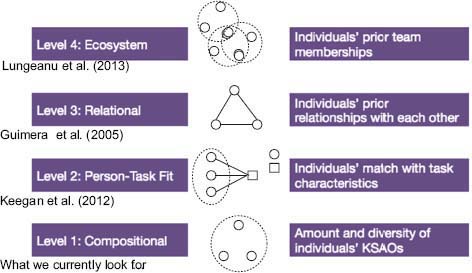

To begin her analysis, DeChurch defined what she meant by “team assembly.” “I’m arguing that we need to move outward from thinking about composition as the totality of all the factors that influence the formation of teams,” she said. DeChurch explained that currently the literature emphasizes only one level of factors, called team composition, but she believes there are at least four levels that should be considered. She referred to these four levels, or ways of thinking about what is important in determining the functioning of a team, as “team assembly mechanisms,” which are illustrated in Figure 4-4.

A Level 1 mechanism considers compositional factors, or what people normally consider when putting together a team: the knowledge, skills, abilities, personality traits, and other individual factors of the team members. Level 2 considers person-task fit, or how the characteristics of the individual team members match up with the tasks the group members will undertake (for example, Keegan et al., 2012). Level 3 examines relational considerations—in particular, the prior relationships that individual team members have had with one another (for example, Guimera et al., 2005). Level 4, the ecosystem level, includes analysis of individuals’ previ-

FIGURE 4-4 Team assembly mechanisms.

NOTES: Citations in Figure 4-4 represent examples of studies that consider a factor at each team assembly mechanism level. KSAOs = knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics.

SOURCE: DeChurch presentation.

ous team memberships (for example, Lungeanu et al., 2013). To illustrate Level 4, DeChurch said that two people on a team who were previously members of the same team will take norms and experiences with them into the new team, based on those prior teams. This level goes beyond prior individual relationships, DeChurch continued, “we are only going to see it if we model the ecosystem, which includes current teams in the context of all the teams that have come before them.”

Team Assembly Modalities

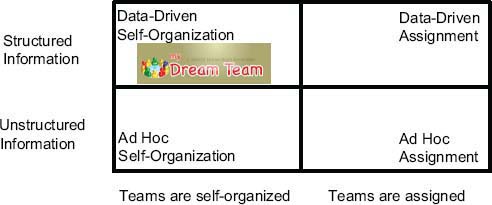

In addition to examining team assembly mechanisms, DeChurch said that it is also important to understand assembly modalities—that is, the way in which teams are formed. For example, team members can be assigned to various teams, or they can self-organize. “Self-organization can take many subtle forms,” she explained. “We can think about the process of an individual applying for a job or a position within a company after having been selected [for the company]. If it is a team-based job, the individual is attempting to self-organize into that team.”

A second way to classify assembly modalities is by the amount of information that is available to form the team. She referred to the information as unstructured if the team assembly took into account information

about the individuals involved but did not consider how the individuals might fit together. On the other hand, if team assembly takes into account information about how potential team members might fit together, it is using structured information. Thus, DeChurch said, there are two important factors that arise from the modality of team formation. “One of them is the degree of control and agency that’s involved, and the second is the amount of information about the mix of people that’s put forth in assembling a team.” These two variables define four separate modalities of team assembly, which DeChurch illustrated with Figure 4-5.

Thinking about team assembly in terms of mechanisms and modalities raises a number of research questions, she said. First, how do the modalities affect the mechanisms of assembly? What effect does the amount of available information or the degree of agency have on team assembly mechanisms, team relationships, and, ultimately, team performance? Second, what is the relative impact of the different mechanisms on team processes, states, and performance? Third, what are the intervening variables through which assembly at these four levels comes to impact team performance? And fourth, which individual differences predict preferences for different modalities? In the remainder of her presentation, DeChurch provided preliminary data to answer the first of these suggested research questions.

The Effect of Modality on Team Assembly Mechanisms

To test the effect that modalities have on the fundamentals of how teams form, DeChurch and her colleagues recently carried out an experiment with 95 students who formed into 30 teams, each of which had 3 to 4 members. The experimental teams were composed of psychology students working on a semester-long project that required them to apply

FIGURE 4-5 Team assembly modalities.

SOURCE: DeChurch presentation.

findings on attitude and behavior change to aid in the commercialization of a scientific breakthrough.

The individual students chose how they would assemble into teams, DeChurch explained. “They had three choices. They could allow the instructor to randomly put them on a team, they could self-organize ad hoc, … or they could use a tool that we built called the My Dream Team Builder,” which was essentially a recommendation system that helped students decide who they might want to be on a team with—that is, data-driven self-organization. Sixty-one of the students chose to use the tool to self-organize, 11 chose ad hoc self-organization (for example, they chose to be on a team with friends), and 23 chose to be randomly assigned. “This resulted in 6 teams in which the dominant modality was assignment, 9 that we’ll call blended assembly—they had some level of assignment and some level of self-organization—and 15 that were matched purely using this builder.”

Within each team, the investigators measured a variety of Level 1 assembly factors—gender, age, personality, intercultural sensitivity, and so on (for background on factors assessed, see Chen and Starosta, 2000, and Donnellan et al., 2006)—and one Level 3 factor: the individuals’ prior social networks. Four weeks after the teams were formed, relationships among teams were measured using sociometric surveys that captured the patterns of communication in a team, the efficacy of communication, people’s confidence in their ability to work with each specific member of the team, their trust in the others on the team, and their reliance on one another for leadership of that team.

As a comparison, DeChurch likened the My Dream Team Builder tool to Amazon’s recommender system for products or Netflix’s system for movies, she said, “only ours recommends people you might want to form a team with.” People who used it provided information about their attributes and their social networks. They also answered questions about the sorts of people they would like on their team. They could specify, for instance, which skills were more important for team members to have and which were less important. They could specify a preference for teammates with significant prior leadership experience or little experience, or they could choose to ignore prior leadership experience entirely. They could specify a preference for people they have enjoyed working with in the past, people who are friends of friends, people who are popular, people who are social brokers—that is, who are connected with numerous groups that are not directly connected to each other—and so on. Considering all the information submitted, the tool compiles a list of recommended teammates, with profiles of each. Users could then choose to click an “Invite” option on the tool to send a pre-scripted e-mail to the potential teammate, inviting him or her to join the team. That person in turn can respond in

a variety of ways, including “I’m already on a team, do you want to join mine?” or “Sorry, I have to decline.”

Once the teams were formed, DeChurch and her colleagues analyzed how the modalities of assembly affected the assembly mechanisms. They used exponential random graph models, which showed, for example, which people had enjoyed working together in the past and which were now on teams together. After carrying out the analysis, the researchers were able to see how the teams that formed using the builder differed from those that formed using other methods.

The analysis found that teams that had used the builder were more homogeneous in age and also more homogeneous in cultural sensitivity. That was an interesting result, DeChurch noted, “because that’s a deep-level characteristic that, if you formed organically, you wouldn’t be aware of. But it was attended to by the teams using the builder.” On the other hand, the teams using the builder were more heterogeneous by sex. And, not surprisingly, both the teams using the builder and the teams that self-organized without the builder were more likely to contain members who had previously worked together than the teams that were assigned randomly. Thus, although the work is still preliminary, DeChurch sees evidence that the modality of assembly (the four options for degree of control and information) affects assembly mechanisms (the four levels of compositional, person-task fit, relational, or ecosystem considerations) in various ways.

The Effect of Team Assembly Mechanisms on Formation of Team Relationships

In testing whether team assembly mechanisms explained the relationships that formed in the teams, DeChurch and her colleagues modeled those relationships in two different ways. First, they modeled the dependent variable as a typical team-level variable, using sociometric surveys to capture the relationships within the team, asking every person about their relations with every other person, and computing a density score for trust, communication, efficacy, and leadership. In the second approach, they modeled the dependent variable as a dyadic relationship.

In the first approach, a regression analysis showed relationships similar to what had already been seen in the literature (for a review, see Bell, 2007). For Level 1 assembly mechanisms, the main effect was seen for mean extraversion in the group, which was associated with greater trust, communication, and efficacy in the group. There were no significant effects for percent female, mean conscientiousness, mean intercultural sensitivity, or age difference (coefficient of variation). For the Level 3 assembly mechanism (prior relationships), there was a significant effect for leadership but not for trust, communication, or efficacy.

However, when DeChurch analyzed the same variables at the dyadic level using Exponential Random Graph Models, the data revealed much more detail about the characteristics that predicted relationship formation in teams. The analysis allowed her to take into account the traits of the sender in the dyadic relationship, the traits of the receiver, aspects of their relationship, and endogenous structural controls. It also allowed her to jointly consider the unique contribution of each factor (i.e., sender characteristics, receiver characteristics, relational variables, and endogenous controls) in predicting the likelihood that a particular type of tie will form (e.g., a trust tie) while accounting for the influence of all the other factors included in the model.

This analysis, DeChurch reported, showed a number of significant effects. For example, trust ties were more likely to form when the sender—the person doing the trusting—was female. “They are also more likely to form when the receiver—the person you’re talking about, do you trust them—is either extroverted or high in conscientiousness. And they are more likely to form if there’s a prior relationship.” Similarly, leadership ties were more likely to form in teams when there was a prior relationship or when the person being rated as a leader was high in conscientiousness. People were more likely to communicate with those who were high in intercultural sensitivity, and people were more likely to feel they could have an efficacious working relationship with someone who was an extrovert.

The last question DeChurch discussed was whether the way that a team formed changed the relationships that developed within it. “It’s essentially the question of, does the dating affect the marriage in teams,” she explained. “And it does.”

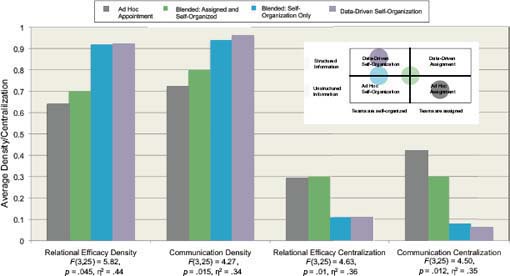

She analyzed how four variables—relational efficacy density, communication density, relational efficacy centralization, and communication centralization—varied according to whether the assembly modality was ad hoc appointment (i.e., random assignment), a blend of assigned and ad hoc self-organized, completely ad hoc self-organized, or data-driven self-organized (see Figure 4-6).

DeChurch’s analysis also found that teams whose members all played a role in their organization, either by using the team builder tool or simply by choosing their friends, communicated more and were more confident in their ability to work together effectively than teams with any members who were appointed, even if three of the four team members were self-organized. Furthermore, the teams whose members all played a role in the organization talked more evenly. “So communication is not going through one person, it is going through multiple people, and they are also more balanced in their efficacy,” DeChurch said. “So they are not just confident that they can rely on one person, but everyone is confident in the ability to work with everybody else.”

Thus, DeChurch summarized, the study offers several intriguing indications of how the team assembly process can affect the team’s ultimate performance. “We’re seeing evidence that the modalities of how teams assemble are fundamentally changing the information that they are attending to,” she said. For example, data-driven self-assembly, as done with the team builder program, allows people to consider deep-level characteristics when choosing team members. “Intercultural sensitivity is something you couldn’t know about. So this opens up a lot of interesting possibilities about information that can be considered in advance to make a team more effective that previously would have been unavailable without some sort of infrastructure.”

These new possibilities, in turn, suggest three new directions in team staffing and assembly. First, she said, programmatic research on team assembly mechanisms is needed that considers all four of the levels rather than just one. Second, programmatic research examining the consequences of team assembly modalities is needed. “We need to think systematically about how tinkering with the formation of teams comes to impact the nature of the relationships that develop within the teams.” Finally, it will be important to take relational analyses seriously. “In organizational behavior we all love to say, ‘We have individuals who are nested within teams who are nested within organizations,’ but that is not really what teams look like,” DeChurch said. “We have individuals, and we have dyads that form patterns of relationships which constitute team-level phenomena.” In other words, according to DeChurch, the team-level phenomena emerge from the dyadic relationships, and studies that are more relational in nature may be the key to detect the effects of team assembly on team performance than studies that aggregate everything.

The roundtable discussion after the presentations from the panelists on Group Composition Processes and Performance touched on a number of issues related to the understanding and measurement of group-related characteristics.

Military Applications

Invited presenter Paul Sackett (presentation summarized in Chapter 5) started one line of discussion by asking about group-relevant information that might be collected pre-accession. At that point in the military recruitment process, he noted, there is no information about what exactly an individual might be doing or what team he or she might be joining. Later,

when jobs are assigned and teams are formed, Sackett said, it will clearly be valuable to have access to information that offers insights into how an individual will perform on a team. So, what information should be collected at the pre-entry stage, he asked, before anything is known about which teams the individual might join?

Gerald Goodwin, of the U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences (ARI), modified and expanded Sackett’s question. “There essentially are three types of decisions that we are considering this information to make,” he said. “One is the selection decision: Do you get into the military? One is the classification decision: What occupation or job can you have? And the third is the assignment decision: What unit do you get assigned to, where do you go?” Thus, different types of information will be needed at different times. “What information would you want to get pre-accessioning—which is where we collect most of this information,” Goodwin asked, “and what information would you want to get somewhere else, and when and where would you want to get it?”

Woolley replied that social perceptiveness and communication skills are two things that could be measured in the pre-accession phase to increase the likelihood that recruits will perform better on teams. Tannenbaum added that most group-related characteristics appear to be more relevant to assignment than selection. That comment led to a discussion on when these assessments should be made, and Tannenbaum noted that it might make sense to do the assessments in the pre-accession phase, since they do not take too long to complete and would then be available for future assignment decisions. That would only work, however, if the traits were stable over time. Because recruits are often about 18 years old and entering a new phase of their lives, the stability of some of these traits may be an issue. For example, Tannenbaum continued, he does not have the necessary data to say with certainty that TREO scores would be stable. If the evidence indicates that they are not always stable, then it would be necessary to carry out the tests later than pre-accession and closer to the time that soldiers are assigned to their teams.

Following up on that point, Sackett said, “Let’s assume [the attribute being measured is] stable, or let’s assume we’re making an assignment decision shortly enough after accession that you’re not worrying about instability. Is there any reason per se to have the information pre-accession, or is it simply needed pre-assignment?” Tannenbaum replied that the main reason to do it pre-accession would be because there is already a testing mechanism in place, and the group-related measures could be jointly administered. On the other hand, he said, given the large numbers of applicants who never enlist or who do not make it through basic training, it might make sense to hold off, if there is some

later point at which it is convenient to assess soldiers’ group-related characteristics.

DeChurch then offered a reason to administer the tests during pre-accession testing. Because the research indicates that some combinations of team members may be more effective than others, it may make sense to try to have a good distribution of recruits in terms of the different traits they bring to teams. Otherwise, once the soldiers are assigned to teams, it may turn out that there are not enough of some types of team members and too many of others—not enough innovators, say, or too many doers—and some teams will end up with a less than optimum collection of members. So, she said, it might be useful to have a better idea of team factors that should be considered during the selection process.

The assignment phase may benefit the most from assessments of group-related characteristics, Tannenbaum suggested. For example, TREO could prove to be quite useful in assisting assignment decisions, as it allows for multiple variables to be maintained and manipulated simultaneously when considering potential team combinations. DeChurch added that, when assembling groups, she considers it important to know about previous relationships among the potential team members. So she sees value in taking into account the Level 3 (relational) and Level 4 (ecosystem) compositional factors from her model. This would probably not be useful for soldiers during their first assignments, she added, since they will be unlikely to have worked with any of their team members before joining the Army, but it will be an important consideration in later assignments.

Woolley reinforced Tannenbaum’s comments by saying that, while the individuals’ skills, abilities, and interests are important to take into account when assigning people to a team, what the team members do in combination will be as important, if not more important, than their individual capabilities. “All of the research presented [at the workshop] strongly suggests that there is a combination of capabilities that comes together and influences how the unit performs and that needs to be taken into account in making these assignments,” Woolley said. Testing to inform team selection does not have to be administered during the initial screening of recruits, she added, but it will likely be beneficial to conduct in the early stages of a soldier’s career.

Adaptability

Paul Gade, a research professor at George Washington University and previously on the ARI staff, introduced the issue of adaptability by describing a study of surgical teams in a shock trauma center (Klein et al., 2006). The study found that the individuals on the team changed their

roles, who was in charge, and how the team functioned, depending on what the situation was and who was the best qualified to make decisions in that particular situation. Could such adaptability be included in assessments, he asked, and would it be an individual measure of adaptability or would it be a team measure that was either in place of or in addition to individual adaptability?

DeChurch answered that it is important to think about where team adaptability resides, and she suggested that it can be found more in the processes and the states of teams, rather than in their performance. For example, do the team members understand where the different types of knowledge and skills on the team lie? Knowing that could help predict how well the team members could adapt if they were given a different task or if something in the environment changed. “I think understanding adaptability is really understanding the nature of the interactions in teams and the collective properties,” she said.

Building on DeChurch’s comment, Woolley noted that her own data linking collective intelligence with learning suggest that collective intelligence probably plays a large role in adaptability as well. “There are various definitions of learning in the literature,” she said, “but almost all of them include some level of adaptation when you’re talking about it at the group level. So I would say that the same principles that enhance collective intelligence in groups probably also enhance adaptability.”

Tannenbaum added that there are probably some individual correlates to adaptability as well. Openness to learning and other personality traits in team members are likely to have at least a small relationship with the adaptability of the team. Still, he said, team adaptability is probably related more to the mix of who happens to be on the team, as well as the culture of the team and the surrounding organization. For example, is it acceptable for someone on the team to step up and say, “I’m not the designated team leader, but I’m going to speak up here”? This is an important factor in the medical world, he said. “The extent to which the attending surgeon sets the stage before an operation has way more to do with whether people are likely to speak up and say, ‘Sorry this is the wrong leg you’re about to operate on’ than [with] individual personality variables. So I think the intervention point there is probably more at the team level.”

Tannenbaum added that a related concept is team resilience, which he characterized as referring to how teams respond when they find themselves in difficult situations—and whether they do it in a way that maintains resources and team functionality in addition to just getting through it. “What’s interesting about it,” he said, “is that at the team level it’s different than at the individual level.” For instance, a team could be composed of members who are all very individually resilient—they are not likely to succumb to post-traumatic stress disorder—but they may not be

great team members, and the team itself does not end up being resilient. So this is another team variable that may be beneficial to consider at the collective level, he concluded.

The Issue of Sufficient Data

Committee member Patrick Kyllonen observed that a fundamental challenge to doing research on teams is collecting sufficient data. It is already difficult to obtain sufficient data to facilitate research on individuals, he said, and the history of intelligence research has had a number of “false alarms” that resulted from sample sizes that were too small. Research on teams requires even more data, Kyllonen continued, in part due to the fact that each team has multiple individuals, but there are other reasons as well. As an example, he noted that DeChurch’s claim that research on teams should involve Level 3 and Level 4 observations means that one will need data on individuals’ prior relationships with each other and on individuals’ prior team memberships.

Kyllonen asked what strategies are available for gathering the large amounts of data that will be necessary for this sort of research. “To get to these higher levels, it’s going to require not tens or hundreds, but it’s going to require [data on] thousands of people to get anything at all gen-eralizable,” he said.

Tannenbaum acknowledged that this is a serious problem. “As the unit of analysis goes up, it’s more difficult to gather data.” It is harder to gather data at the team level than at the individual level and harder to gather data at the organizational level than at the team level, he said. If the payoffs seem great enough, then it might make sense to carry out “unobtrusive measurements” on Army teams that have already been assembled and are operational, specifically to gather data to use in analyses. But the field is still in its infancy, he suggested, and “at some point there may be some breakthroughs that occur that allow data to be gathered more readily from existing teams that we could use in future research.”

DeChurch offered two additional suggestions to facilitate data gathering on teams. One was to use longitudinal research. “I think we have to get beyond the variances between teams and look more meaningfully at modeling the variance within a team over time.” Gathering data over time may make it possible to access much more explanatory power than is possible with static measurements. Her second suggestion was to build a community infrastructure and use it to link and share databases. As has been done in other areas of science, rules could be instituted that a paper would not be accepted for publication unless the researchers submitted their data to the central repository so that other researchers could have access to it.

Aggarwal, I., and A.W. Woolley. (2013). Do you see what I see? The effect of members’ cognitive styles on team processes and errors in task execution. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 122(1):92-99.

Aggarwal, I., A.W. Woolley, C.F. Chabris, and T.W. Malone. (unpublished). Learning How to Coordinate: The Moderating Role of Cognitive Diversity on the Relationship Between Collective Intelligence and Team Learning. Carnegie Mellon University Working Paper. Abstract available: http://works.bepress.com/anita_woolley/1 [July 2013].

Baren-Cohen, S., S. Wheelwright, J. Hill, Y. Raste, and I. Plumb. (2001). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test” revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(2):241-251.

Bell, S.T. (2007). Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3):595-615.

Bell, S.T., A.J. Villado, M.A. Lukasik, L. Belau, and A.L. Briggs. (2011). Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3):709-743.

Chen, G.M., and W.J. Starosta. (2000). Intercultural sensitivity. In L.A. Samovar and R.E. Porter (Eds.), Intercultural Communication: A Reader (pp. 406-413). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Deary, I.J. (2000). Looking Down on Human Intelligence: From Psychometrics to the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press.

Donnellan, M.B., F.L. Oswald, B.M. Baird, and R.E. Lucas. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2):192-203.

Engel, D., A.W. Woolley, L.X. Jing, C.F. Chabris, and T.W. Malone. (unpublished). Reading the Mind in the Eyes Predicts Collective Intelligence, Even Without Seeing Eyes. Available: https://mitsloan.mit.edu/about/detail.php?in_spseqno=51955 [July 2013].

Guimera, R., B. Uzzi, J. Spiro, and L.A.N. Amaral. (2005). Team assembly mechanisms determine collaboration network structure and team performance. Science, 308(5722):697-702.

Keegan, B., D. Gergle, and N. Contractor. (2012). Do editors or articles drive collaboration? Multilevel statistical network analysis of Wikipedia coauthorship. In S. Poltrack and C. Simone (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) (pp. 427-436). New York: Association for Computing Machinery. Available: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2145204.2145271 [July 2013].

Klein, K.J., C.J. Ziegert, A.P. Knight, and Y. Xiao. (2006). Dynamic delegation: Shared, hierarchical and deindividualized leadership in extreme action teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(4):590-621.

Lungeanu, A., N.S. Contractor, D. Carter, and L.A. DeChurch. (2013). A hypergraph approach to understanding the assembly of scientific research teams. In D. Carter (Chair), Teams on the Hyper-Edge: Using Hypergraph Network Methodology to Understand Teams. Symposium conducted at the Interdisciplinary Network for Group Research Conference, July, Atlanta, GA. Presentation information available: https://www.conftool.net/ingroup2013/index.php?page=browseSessions&form_session=3&CTSID_INGROUP2013=RHaHuEd1CuQISf6V3MS6t85TnJ1 [July 2013].

Mathieu, J.E., S.I. Tannenbaum, J.S. Donsbach, and G.M. Alliger. (2013). Achieving optimal team composition for success. In E. Salas, S.I. Tannenbaum, D. Cohen, and G. Latham (Eds.), Developing and Enhancing Teamwork in Organizations: Evidence-based Best Practices and Guidelines (pp. 520-551). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mathieu, J.E., S.I. Tannenbaum, M.R. Kukenburger, J.S. Donsbach, and G.M. Alliger. (unpublished). Team Role Experiences and Orientations: The Development of a Measure of Tests of Nomological Network Relations. Available: http://admin.business.uconn.edu/PortalVBVS/DesktopModules/Staff/staff.aspx?&uid=’mathieu [July 2013].

Myaskovsky, L., E. Unikel, and M.A. Dew. (2005). Effects of gender diversity on performance and interpersonal behavior in small work groups. Sex Roles, 52(9):645-657.

Spearman, C. (1904). “General intelligence” objectively determined and measured. American Journal of Psychology, 15(2):201-292.

Stewart, G.L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of relationships between team design features and team performance. Journal of Management, 32(1):29-55.

Tannenbaum, S.I., J.S. Donsbach, G.M. Alliger, J.E. Mathieu, K.A. Metcalf, and G.F. Goodwin. (2010). Forming Effective Teams: Testing the Team Composition System (TCS) Algorithms and Decision Aid. Paper presented at the 27th Annual Army Science Conference, Orlando, FL. Available: http://www.groupoe.com/groupoe-company/team/97-scott-tannenbaum.html [July 2013].

Woolley, A.W., C.F. Chabris, A. Pentland, N. Hashmi, and T.W. Malone. (2010). Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science, 330(6004):686-688.