Issues Overview for Observational Studies in Clinical Research

KEY SPEAKER THEMES

Goodman

• The choice between an observational study and a randomized controlled trial (RCT) is not binary.

• No algorithm exists for determining whether an observational study or an RCT is best for answering a specific question.

• The distinctions between observational studies and RCTs can be subtle, and interventions are changing in a way that requires studies with designs that can evaluate complex interventions.

• The design of a study needs to consider the context of a research program and the fact that different decision makers have different information needs.

To set the stage for the workshop’s presentations and discussions, planning committee member Steven N. Goodman, Associate Dean for Clinical and Translational Research at the Stanford University School of Medicine, highlighted some of the issues involved in the use of clinical data, whether it be from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or an observational study, to draw conclusions that are relevant to the health care decisions made by physicians and their patients.

PRESSING QUESTIONS FOR CONSIDERATION

With apologies to Charles Dickens, he portrayed the complexities of using data from the two types of clinical studies and the inability to resolve the intellectual differences that characterize the field of clinical trials today as being analogous to Paris in pre-Revolutionary France. “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” Goodman began, “It was the age of Clinical Trials, it was the age of Observational Studies, it was the epoch of Data Mining, it was the epoch of Prespecification, it was the season of Discovery, it was the season of Decision, it was the spring of Effectiveness, it was the winter of Harms, we had Truth before us, we had Lies before us, we were all going direct to Causality, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was the present period, and some of its noisiest funders and policy makers insisted on its being perceived, for good or for evil, with a superlative degree of scientific rigor.”

He then discussed a recent example from the popular press illustrating the challenges to the use of data from observational studies to develop treatment plans for individual patients. In this example, a statistician used one set of data to publish two papers whose findings on the health benefits of walking versus running appeared to contradict one another on the surface. However, the two papers were looking at different endpoints: one was looking at a surrogate endpoint, blood lipid levels, whereas the other was looking at weight loss. Goodman explained the resulting conundrum as such: the bottom-line advice for a specific patient depends on whether the patient wants to lose weight or control blood lipids, and that choice depends on multiple factors that were not included as variables in the study that generated the data.

Goodman cited the conflicting findings for hormone replacement therapy between a large number of observational studies and the RCT conducted by the Women’s Health Initiative. Although as another example of why observational studies by themselves can provide misleading advice for patients, the former studies had demonstrated that hormone replacement therapy had a protective effect against heart attacks and the Women’s Health Initiative study reported that hormone replacement therapy was associated a small increase in the risk for acute coronary outcomes. A reanalysis of the observational data pointed out important methodological flaws in the designs of both trials and found that the discrepancies could be resolved through a different conceptual framing of both the observational studies and RCTs (Hernán et al., 2008). According to Goodman, the insights from this reanalysis and the way in which it paired the two types of studies showed that “observational studies and RCTs are getting closer and closer. The choice between them is really not, in a sense, a choice between them but involves a lot of complicated trade-offs and questions about what each one reveals that the other one does not.”

He then described what he called the foundational equation of epidemiology: Pr(outcome | X = x) = Pr[outcome | set(X = x)]. He explained this equation to mean that the probability (Pr) of an outcome with an observed risk factor (X) is equal to the probability of that outcome when that risk factor is set equal to the same value (x). The equation can also be posed as a question: Is the observed effect the same as the effect seen when the variable is actively manipulated? If the answer to that question is “yes,” then the result of the observational study can be transferred into the realm of practice.

Goodman noted that two prior reports—Ethical and Scientific Issues in Studying the Safety of Approved Drugs from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2012) and Our Questions, Our Decisions: Standards for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Methodology Committee (2012)—posed the same challenge facing the participants of the workshop described here, namely, determine the proper role for observational studies and RCTs in patient-centered outcomes research.

For the IOM study, two of the planning committee’s charges were to (1) identify the strengths and weaknesses of the abilities of various approaches, including observational studies, patient registries, meta-analyses, meta-analyses of patient-level data, and RCTs, to generate evidence about safety questions and (2) determine what types of follow-up studies are appropriate, considering the speed, cost, and value of studies, to investigate different kinds of signals—detected before or after approval of a medication or device—and in what temporal order these studies should be conducted.

Goodman, who worked on both reports, noted that answering the second part of this charge was particularly difficult because experts can disagree for many legitimate reasons on the conclusions to be drawn from any particular dataset. As a result, no formulaic, algorithmic method is able to determine what types of studies are needed and in what temporal order studies should be conducted to answer a specific clinical question. Indeed, he explained, the decision to choose between an observational study and an RCT depends on multiple factors, including

• the size and nature of the signal,

• the size of the effect needed to justify a change in policy,

• temporal urgency,

• other potential causes of the outcome and whether the study will look for intended or unintended consequences,

• the quality and the availability of data,

• transportability, and

• the analytical approach as well as the study design.

In the report from PCORI, Goodman and his colleagues on the Institute’s Methodology Committee came up with essentially the same recommendation presented in the IOM report: the choice between an observational study and an RCT is not binary, and no algorithm for determining which type of study is best for answering a specific question exists.

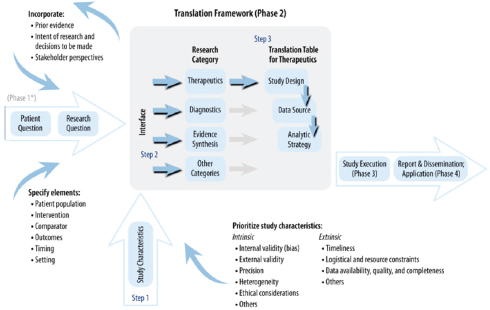

Rather than propose a specific translation table that would provide guidance to PCORI’s board to determine research methods that are most likely to address each specific research question, the PCORI Methodology Committee developed a translation framework (see Figure 2-1) that considered the same factors identified in the IOM report. One key aspect of this framework is that it recommends that the research question and the trial design be kept separate to provide a focus for clarifying trade-offs. Another is that the framework recognize that many kinds of decision makers exist and that the information that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services needs to make a decision about reimbursement issues is not going to be the same as the information that a clinician needs to make a decision at a patient’s bedside. As a result, study design needs to consider the context of a research program and not the needs of one specific study. The framework also stresses that the study design must account for state-of-the-art research methodologies. Goodman cited his earlier example of the Women’s Health

FIGURE 2-1 Phase 2 of PCORI translational framework to guide design of new clinical comparative effectiveness studies for specific research questions.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from PCORI.

Initiative study to support the importance of using the best methodologies available.

Goodman noted that in both of these reports the role and place of observational research in the world of therapeutics are central. His impression, based on his work on these two reports, is that there seems to be a strong need to apply the same, somewhat formulaic rules of evidence and design familiar to individuals in the world of evidence-based medicine to observational data. This need is apparent in the demand to create rules, or at least a social consensus, about what constitutes legitimate study designs for various questions. In his mind, the best approach is to articulate principles for discussion rather than frame the question of study design as a binary choice based on specific rules.

Turning to the perceived strengths and weakness of RCTs and observational studies, Goodman said that most positions on the strengths and weakness of RCTs and observational studies are extreme and tend to be caricatures of reality. He encouraged the workshop participants to not put themselves into doctrinaire camps along the lines that suggest that observational studies are generalizable and RCTs are not, that observational studies provide patient-centered individualized evidence and RCTs do not, that bias is minimal in RCTs but high in observational studies, or that data quality is high in RCTs but low in observational studies. For each one of these canards, he explained, study designs can make the two types of studies nearly equivalent. What is true, he said, is that the distinctions between observational studies and RCTs can be subtle and that interventions are changing in a way that requires that studies for the evaluation of these interventions have designs that are able to evaluate complex interventions. He noted that the field is facing a time when it has not only more data but also different types of data and more complex data. He added that the emphasis on transparency, reproducibility, and wider engagement in the scientific process is growing and that this emphasis can only benefit patient-centered outcomes research.

In his closing remarks, Goodman listed what he considered to be the central questions that he hoped the workshop would address:

• Does the method that is being talked about address the question we are really interested in?

• Does the method correctly estimate the effect for those to whom the results are applied? If not, how wrong is it?

• Does the method get the uncertainty right? If not, how wrong is it?

• Which of the approaches discussed at the workshop would be sound enough to guide a treatment decision? Would you bet a life on it? If not, could the field get there, and what would it take?

He also listed the key decisions that PCORI faces. First, it needs to determine what methodologies it should use in studies planned for today. Second, to determine the new methodologies in which it should invest, it needs to select the methodologies with the potential to yield the greatest benefits to patient-centered research. Finally, PCORI needs to establish the set of methods that will be taught to the next generation of those who will engage in patient-centered outcomes research.

During the discussion that followed Goodman’s presentation, a number of participants stated the importance for researchers to first ask the right questions needed to make a clinically meaningful decision and then choose the study design and methodological tools to best answer those questions. Too often, participants commented, decision makers do not know the question that a study is answering and researchers do not delimit the question that they are asking or put a study into context, making the decision maker’s job more difficult than it should be. Joel B. Greenhouse, professor of statistics at Carnegie Mellon University, wondered if it would be possible for the scientific community to reach a majority consensus as to what those important questions should be.

Harold Sox, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, suggested that questions be framed in a way that generates data on uncertainties about outcomes. Such information would help patients and physicians make clinical decisions that have the right balance between potential harms and benefits for a particular patient. Mitchell H. Gail, senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute, responded by stating that the combination of RCTs and observational studies could provide an important understanding of how risks and benefits should be weighed across the baseline of people with various characteristics.

Several participants commented that the amount of data from observational studies that will be available to researchers will soon dwarf by several orders of magnitude the amount of data from RCTs. Marc L. Berger, vice president of real-world data and analytics at Pfizer, said that the real issue will not be whether observational data will be used but will be how they will be used. Sally C. Morton, professor and chair of the Department of Biostatistics in the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh, added that many of the data that will be available will not come from designed studies and that different types of statistical methods will be needed to address what is essentially a model that is backward from the traditional situation in which data come from a study. James Robins, professor of epidemiology at Harvard University, proposed that the Internet data analytics community be evaluated to determine the questions to be

answered when vast amounts of data have been collected but researchers do not have a question in mind. In particular, he mentioned that marginal structural modeling has the potential to be used to extrapolate patient-specific recommendations from large sets of clinical data.

Robert Temple, deputy director for clinical science at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, asked for examples of situations in which it was not possible to generalize the results of a clinical trial to a real population. In his experience, this has not, in fact, been the case. Goodman responded that the more context specific that a medical intervention is—and, in particular, when the intervention is something other than a drug-based therapy—the more likely it is that it will not be possible to generalize from the results of an RCT.

Hernán, M. S., A. Alonso, R. Logan, F. Grodstein, K. B. Michels, W. C. Willett, J. E. Manson, and J. M. Robins. 2008. Observational studies analyzed like randomized experiments: An application to postmenopausal hormone therapy and coronary heart disease. Epidemiology 19(6):766–779.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. Ethical and Scientific Issues in Studying the Safety of Approved Drugs . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Methodology Committee. 2012. Our Questions, Our Decisions: Standards for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research . Draft Methodology Report. Washington, DC: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. http://pcori.org/assets/MethodologyReport-Comment.pdf (accessed May 14, 2013).