3

Strategic Research for Integrated Water and Environmental Management

The previous chapter provides the rationale for a systems approach to deltaic research, and for integrated water and environmental management. This chapter builds upon these themes with a set of strategic research opportunities that could be part of a systems framework. The identified research needs are broad, especially in comparison with specific disciplinary topics. They reflect a strategy based on initial research that focuses on large-scale, near-term questions in the Mississippi River delta region, and proceeds toward longer-term studies, including comparative international research. As the Water Institute plans to use this report in part for “strategic planning” purposes, it may find it useful to examine recent research on strategic planning and schools of strategy formation (e.g., Mintzberg, 2007).

Some of the research opportunities identified below might be pursued separately, or they might be combined into a single broader study. For example, the value of preparing a synthesis of research on the Mississippi River delta is discussed; and also, conducting a Condition of the Delta assessment that would yield a baseline study for restoration experiments. For clarity, they are presented separately below; but it may also be possible to combine them.

Past research in the lower Mississippi River and its delta is extensive. It includes studies of hydrology, sediment dynamics and erosion, effects of severe storms, coastal effects of oil spills, ecological conditions in freshwater

and tidal marshes, commercial fisheries, infrastructure, human demographic processes, and the built environment (cf., CPRA, 2012 appendices; Lower Mississippi Region Comprehensive Study Coordinating Committee, 1974-1975; and State of the Coast conference proceedings, 2010, 2012).

There apparently is no synthetic overview of the current state of knowledge on this broad range of topics, which link the lower Mississippi River valley with the coastal zone. The lack of a comprehensive synthesis inhibits broad systemic understanding of the research landscape, knowledge gaps, general findings and conclusions, key uncertainties, and related error bands or confidence intervals.

A vast body of relevant water resources and related research has been conducted over past decades in the lower Mississippi River region, and for the Louisiana 2012 Coastal Master Plan (e.g., Mesehle et al., 2012a). A synthesis of these large bodies of research could present broadly useful basic information, and interpretations of hypotheses that have been tested or that currently may be either widely accepted or controversial. A synthesis document of this type could promote a sense of perspective and community among research organizations in the delta. The synthesis could be revised periodically (e.g., 5-year intervals), and could be supported by a modern archiving system designed around science and engineering programs and activities relevant to the delta environment.

Similarly, although enormous bodies of research on the Mississippi River delta have been undertaken, there does not appear to be a comprehensive “institutional map” of that research (i.e., a systematic chart of research organizations, major projects, archival collections, etc.). Likewise, there apparently have not been detailed historical assessments of how the Mississippi River delta has been compared with other deltas around the world (although see Roberts and Coleman, 2003, on the history of the LSU Coastal Studies Institute). As large-scale research on restoration projects unfolds, a research synthesis, institutional map, and historical review would have immediate as well as long-term value.

• Preparation of a Mississippi River delta Research Synthesis report offers a research opportunity for the Water Institute. This report could, for example, include an institutional map of major research programs and resources. It would require a robust geographic definition of the delta, a historical review of Mississippi River delta research and development, and a perspective on the international context for research.

CONDITION OF THE DELTA ASSESSMENT

One challenge for understanding and predicting the behavior of a complex system is establishing a baseline for comparison. A baseline should be an integrated dataset of the state of the system over some relatively short time that can be considered a “snapshot” of the system. For a system such as the lower Mississippi River delta that is studied by scientists from a variety of disciplines, prior research projects have been conducted using baselines developed at different times or in different locations that are relevant to the specific hypothesis being tested. Without a common time-space baseline, it will be difficult for future research to examine quantitatively the cross-disciplinary effects associated with complex interactions.

Biennial State of the Coast conferences in Louisiana result in a compilation of many valuable papers on deltaic science but do not purport to provide an integrated synthesis or baseline.1 The Louisiana 2012 Coastal Master Plan appendices compiled datasets for modeling and screening, and a variety of spatial data platforms have been created over time. Examples include Atlas—the Louisiana Statewide GIS; CLARIS (coastal resource information system); CLEAR (coastal ecosystem assessment); LAGIC (Louisiana Geographic Information Center); and SONRIS (natural resources including oil and gas). Establishing a State of the Delta assessment across data platforms on water, landscape, and human factors, and supported by short-term field data collection to fill strategic gaps, could provide a valuable baseline for long-term research.

This baseline could be described as a Condition of the Delta Study. Such a study would entail significant collaboration among the many research institutes and investigators who work in the delta (as well as significant external funding). The study could employ existing environmental monitoring instruments for use across broad swaths of the delta for a common time period.

An expected advantage of a Condition of the Delta Assessment in the early years of the Water Institute’s development is that it will require developing communication channels and dialogue across the research institutions working in the region. Scientists from disparate disciplines can be convened, which could provide connections that lead to extramural funding from interdisciplinary programs.

An international analogue for a Condition of the Delta study has been prepared for the Rhine delta (Deltares, 2009). Other international deltas such as the Mekong have also been the subject of database development and edited research volumes, but again this stops short of providing a coordinated baseline assessment (Renaud and Kuenzer, 2012; cf. Deltares,

______________

1 For more information, see: http://www.stateofthecoast.org.

2011a). However, the WISDOM: German-Vietnamese collaboration on the Mekong delta deserves study for its well-structured archiving of interdisciplinary sources that encompass hydrologic and ecological processes, cartographic data layers, time series data, livelihood studies, and information on landscape formation processes.2

• A comprehensive State of the Delta baseline for data across water, landscape, and human factors has not been established. As such, this is a research gap and a research opportunity for the Water Institute and allied organizations.

• The Water Institute could provide the central motivation and coordinating effort for the promising research opportunity of developing a Condition of the Delta assessment. This ideally would be conducted with broad collaboration among stakeholders and scientists working in the Delta.

RESEARCH DESIGN FOR DIVERSION PROJECTS

The State of Louisiana’s 2012 Coastal Master Plan has committed to river diversions and other natural infrastructure restoration projects that are likely to be controversial from scientific and public policy perspectives (e.g., see New Orleans Times-Picayune, 2013). Such projects inherently involve activities that might simultaneously be considered beneficial by one party and harmful by another. Furthermore, uncertainties associated with understanding the interactions among elements of such a complex system ensure that not all consequences and outcomes of these projects can be forecast with precision (see Kearney et al., 2011, and Turner, 1987 and 2011). This makes the outcomes of these projects inherently uncertain (Mesehle et al., 2012b). This setting presents an opportunity for the Water Institute to advance science that supports adaptive management for large-scale ecosystem restoration. Similar future research opportunities for the Water Institute will entail further collaboration and agreement with the Louisiana CPRA.

• The Water Institute could identify key decision-relevant uncertainties in the planned diversion projects, propose building experiments into project and policy designs, and contribute to scientific monitoring of results.

______________

Research for Adaptive Management

Adaptive management in the most general sense means monitoring hypothesized effects of actions, projects, and programs to determine whether the outcomes materialize as expected. Information on those outcomes then is used to recon or adjust the design and operation of a project, and to guide design and operation of future similar projects. A 2004 NRC committee issued a report on adaptive management for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. That report noted some fundamental concepts of the approach, minimal areas of agreement for stakeholders, and expectations from the concept:

Participants in adaptive management programs must at least agree upon key research questions or lines of inquiry to be pursued by an adaptive approach (Lee, 1999). Some agreement on larger objectives could help better define program direction; but if full agreement on ecosystem management goals exists (an unusual condition), there would be a reduced need for adaptive approaches. Adaptive management is a means for bounding and addressing disputes and differences. As adaptive management proceeds, not only will ecosystem understanding by participants increase, but social and political preferences are likely to evolve, and environmental and social surprises may occur. Key questions, paths of inquiry, and programmatic objectives should be regularly reviewed in an iterative process to help participants maintain a focus on objectives and appropriate revisions to them. (NRC, 2004, p. 24)

There is today a rich literature on the theory and practice of adaptive management. Although not possible to comprehensively review and critique here, adaptive management activities often are viewed as ranging from active (or anticipatory), to passive (or reflective), forms. The active form has more controlled and explicit experimental and learning objectives, while a more passive approach adjusts to results of actions that have fewer controls and less explicit learning aims and methods. Pure forms of active adaptive management rarely are possible because of a variety of factors, including limited funding for model development and related scientific research, limits for experimental decisions and regimes, and differing stakeholder preferences and opinion.

Despite the associated challenges, implementation of the Master Plan projects that will soon be constructed, and the policies that are being formulated, offer some excellent opportunities for structured adaptive management (cf., brief chapter in CPRA, 2012). Given the size and many complexities of lower Mississippi River hydrology and ecology, and related social and economic systems, some management decisions will need to be adjusted and improved in the future. Despite extensive work to date, the magnitude of effects for the planned Delta restoration projects on

nutrient levels, marsh creation, and areal integrity of wetlands areas remains uncertain—indeed, one might say that there are mainly hypotheses, which will be tested by the projects. The Water Institute is not an action agency for planning or executing integrated water and environmental management decisions; rather, it seeks to provide scientific support and analysis for policy makers.

Issues of research design, large-scale experiments, and sampling and monitoring protocols are well illustrated by adaptive management programs in other regions of the United States and Europe. For example, the Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center convened peer review panels to define measurement protocols for multiple-experiment research programs on sediment transport, ecological dynamics, and cultural heritage impact assessment (NRC, 1996, 1999). Several decadal experiments with adaptive management in Europe also offer insights into strategic research approaches (e.g., Vermaat et al., 2005 on European coasts; and Deltares, 2012 on the relevance of Netherlands and U.S. programs for East Asia).

Adaptive management in the Mississippi River delta could benefit by surveying experience in the United States. and internationally. As in the Grand Canyon, it could identify common research design and monitoring protocols for restoration project effects, interactions, and performance (Paola et al., 2011). It could anticipate the otherwise confounding effects of extreme events such as hurricanes or severe droughts, ecological “surprises,” and social change by incorporating them as contingencies in research design. Establishment of a “quick response” grant program could collect perishable data to better understand the earliest processes of human adjustment and environmental change (Natural Hazards Center, 2013).

• Design of scientific research to support adaptive management of large-scale ecosystem restoration projects is a significant research opportunity in the Mississippi River delta context.

• As some uncertainties will unfold during the course of diversion experiments, a “quick response” research grant program for internal and external applicants could facilitate rapid collection of perishable data in the event of environmental surprises and hazards.

Long-term monitoring is traditionally the purview of government agencies providing the public information on topics such as environmental changes and trends, public safety, and economic indicators. Data collection for weather, rainfall, streamflow, tides, and water quality variables is a well-established and uncontroversial task of government because of the recognized value of these data to commerce and the public.

A robust adaptive management program needs data collection aimed at proving/disproving the effectiveness of the restoration efforts, and responding effectively to experimental outcomes. Sustained, multidecadal data collection to support a regional-scale adaptive management program would be costly, and perhaps an inappropriate role for the Water Institute and its interests in strategic research. Basic data collection of environmental variables likely is a more appropriate role for federal (e.g., U.S. Geological Survey) and state (Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality). At the same time, there may be opportunities to review ongoing (federal and state) monitoring programs, and provide advice for improvement.

• A research opportunity in complex deltaic systems is to help identify emerging decision-relevant variables and time scales, and then to propose cost-effective adjustments in monitoring programs, including new data sources, methods, and technologies.

RESEARCH ON SETTLEMENT, LAND USE, AND LANDSCAPE CHANGE

The role of land use is critically important for management of deltas but has been addressed in limited ways in water management. Examples of important implications of problematic land use are increased exposure of populations to flood risk, and compromising of floodways’ functionality through settlement and development.

Many human settlements historically have located along rivers. Despite threats from periodic flooding, riverside settlements have ready access to water supply, fisheries, and navigation opportunities. Early settlers in the United States understood the importance of subtle topographic differences, and exploited natural levees along large, meandering rivers (Kondolf and Piégay, 2010). Natural levees form when floodwaters overflow the channel, their velocity slows, and coarser sediments in suspension settle out, building up a berm of sand along the channel margin that slopes gently downward away from the channel into the floodplain. Along the Sacramento River, for example, early settlements were restricted to the natural levee (Kelley, 1989). Likewise, in New Orleans, the older neighborhoods of the French Quarter and Garden District were built on the higher ground of the natural levee of the Mississippi. Away from the river, low-lying floodplain areas were inundated annually and recognized as ill-suited for human settlement. The advent of powerful pumps in the twentieth century made it possible for these low-lying lands to be occupied, but as their soils were exposed to the atmosphere, vast areas subsided below sea level (Campanella, 2002). These fluvial landforms were manifest in the pattern of inundation depths during Hurricane Katrina, with natural levees (of the modern river and

ancient distributary channels such as the Metarie-Gentilly Ridge) either dry or only shallowly inundated, while many floodplain areas were flooded to depths greater than 4 meters.

By comparison, along the lower Mekong River in Cambodia, settlements (often built on stilts) and permanent agriculture (e.g., fruit trees) are located on natural levees, with back-swamp areas used for annual crops (Campbell, 2009). In Bangladesh, artificial flood-control levees have typically failed to control floods, but ironically serve as “high ground” onto which residents take refuge during inundations (Sklar, 1992). Where no high ground is available, people often have taken refuge from floods by migrating from flood-prone areas during the wet season or building elevated structures above anticipated flood levels. In Dadun, a “water village” of the Pearl River Delta in China, the flood of 1962 inspired many residents to build second and third stories on their houses in anticipation of future floods (Bosselmann et al., 2010).

However, with the construction of flood control levees in many of these deltaic regions, the perception that low-lying lands are protected from flooding can encourage development in the “protected” areas behind the levees (White 1945, 1974). All levees provide protection only up to a specified design flood, typically determined based on assessment of risks and costs of various “levels of protection.” In the Netherlands, levees around urban areas are typically built to protect against river floods with return intervals of 1,250 years, while delta and coastal levees are designed to provide 4,000- to 10,000-year flood protection (Jonkman et al., 2008). In the United States, the National Flood Insurance Program uses the 100-year flood (the flood with a 1 percent chance of occurring in any given year) to determine the “floodplain,” and as a consequence, levees are typically constructed to provide protection from the 100-year flood (Kondolf and Podolak, 2013). However, lands behind such levees remain vulnerable to inundation by larger floods, and the “residual risk.” Without levees, the floodplain would be subject to “nuisance flooding” every few years, reminding decision makers and the public that the lands are prone to flooding. However, residents of lands “protected” by 100-year levees often do not fully perceive their residual risk of flooding (Ludy and Kondolf, 2012). By “filtering out” frequent smaller floods, levees may turn a frequently occurring natural hazard, to which society may be relatively well adapted, into an infrequent natural hazard, to which society becomes more vulnerable (Kondolf and Podolak, 2013).

Levees encourage development in floodplains and thereby expose more people and structures to flood damage, which ultimately exacerbates the damages caused by larger floods (Werner and McNamara, 2007). For example, floodplain inhabitants behind levees may perceive that they are fully protected. This may encourage development in fundamentally risky

places, and/or discourage nonstructural measures such as raising buildings above the anticipated flood levels and improving warning and evacuation methods.

Moreover, because land-use decisions are taken at the level of local government, it is often difficult to enforce well-designed policies adopted at the national or state level, the level at which integrated water management is commonly conceived and implemented. Local governments often are motivated strongly to approve new developments in order to benefit from development fees and tax revenues, and local officials may not understand (or choose not to recognize) the real long-term flood risk to development in low-lying lands (Eisenstein et al., 2007). For this reason, empirical research on patterns and trends in floodplain occupance has continuing importance.

Similar problems arise with lands within designated floodways, for which the federal government holds flowage easements. Local governments may issue building permits, or fail to stop unpermitted construction, within the designated floodways. The results can be encroachment of urbanization into the floodways such that flood managers become reluctant to utilize these essential components of the flood management system out of fear of political “fallout” from damaging the encroached developments.

Given the reality of many crucial land-water relationships and linkages, it is essential to coordinate land occupancy issues with management of water to encourage wise economic investments, ensure public safety, and promote long-term ecological protection or restoration. The reality, however, is that given traditional lines of authority and decision making, existing institutions in the Mississippi Delta are unlikely to want to address the issue directly.

• There are research opportunities in the lower Mississippi River delta for analyzing changing land use and building patterns and trends, and for explaining how projects and policies can influence those trends in ways that advance or constrain the paths and prospects for integrated water and environmental management.

River deltas are complex, adaptive systems that evolve constantly in response to changing environmental forces. Medium-term (decadal to century) changes in delta geomorphology occur in response to alterations in river flow and sediment load and to local tectonics. Long-term (thousands to hundreds of thousands of years) delta dynamics are linked to glacial-interglacial cycles. Delta stability reflects a delicate and dynamic balance between incoming sediment load, which grows and stabilizes the delta, versus subsidence, sea-level rise, and erosion, which degrade the delta.

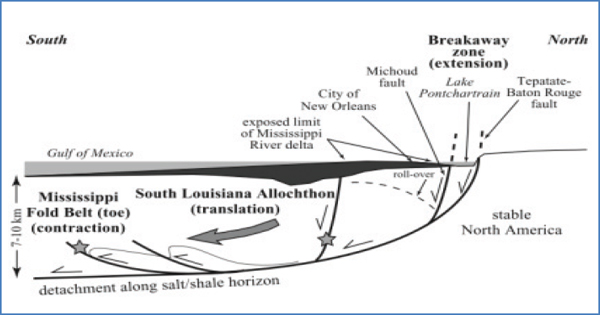

FIGURE 3-1 The South Louisiana Allochthon (large block of rock moved from its original site).

SOURCE: Dokka et al., 2006.

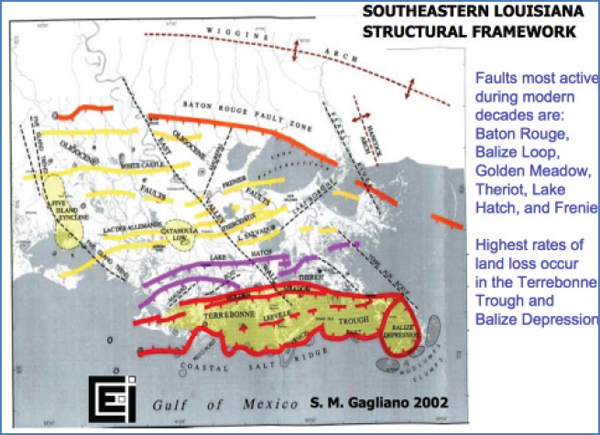

FIGURE 3-2 Fault zones in the Mississippi River delta.

SOURCE: Gagliano, 2002.

Tectonic processes exert a major control on delta stability in the Mississippi River Delta. Since 1930, over 600 square miles of land area south of the Golden Meadows fault zone have been converted into open water habitat by slumping (Gagliano, 2005). The cross-section in Figure 3-1 depicts the structural features and processes, while the map in Figure 3-2 delineates their rough alignment in the lower delta.

The precise fault alignments are not always clear, but much of the region south of this fault zone is inherently unstable, and land loss rates continue at a rapid pace. Although oil and gas and groundwater extraction contribute to land loss in this area, tectonics is a primary driver, and as such it is critical that tectonic stability be considered in regional planning processes.

• More detailed mapping of major geologic areas of relative stability, major land loss vulnerability, and land-building potential could help guide research on diversions and coastal protection project performance.

This page intentionally left blank.