Diabetes Prevention in Native Communities

Speakers from three different communities talked about the work they have been doing in their communities around diabetes prevention and management. Darlene Willis, coordinator of the Diabetes Prevention Program for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, described the wealth of programs she helps administer in the Mississippi Choctaw Health Department. Walleen Whitson, site coordinator with the Lifestyle Balance Program of the SouthEast Alaska Regional Health Consortium (SEARHC), detailed a pre-diabetes program she leads in southeastern Alaska. And Nia Aitaoto, University of Iowa College of Public Health, offered three different perspectives on a set of diabetes programs for Pacific Islanders.

DIABETES PROGRAMS AMONG THE MISSISSIPPI BAND OF CHOCTAW INDIANS

The mission of the Choctaw Health Department in Mississippi, where Darlene Willis coordinates the Diabetes Prevention Program, is to raise the health status of the Choctaw people to the highest possible level. Diabetes is a serious obstacle to that mission, said Willis, and needs to be countered by an integrated set of programs, from the administrative and program levels to research and community involvement.

The Choctaw Health Department has had nationally recognized programs and initiatives in diabetes prevention and management for more than two decades. Today it has about 1,600 people in its diabetes registry—all but one with type 2 diabetes—from a population of about 10,600 people that it serves. The largest numbers of patients are in the 46- to 65-year age

group, but almost as many diabetes patients are 19 to 45 years old. The diabetes education program run by the department has a certified diabetes educator, a nurse, a registered dietician, a diabetes education aide, and an administrative assistant. The Special Diabetes Program for Indians has additional staff, including fitness instructors, a podiatrist, and lifestyle coaches.

Willis outlined many of the activities run by the department’s diabetes programs. Boot camp classes every morning draw community members, including many older members of the tribe. The department visits tribal schools and measures height, weight, body mass index, blood pressure, and blood sugar for all students, and enters the information into a resource and patient management system. The diabetes programs also sponsor activities in schools, such as walks, runs, and other kinds of exercise.

Education and prevention activities extend throughout the year. Willis provided just a partial list of activities that are common in Native communities:

• Health fairs

• Wellness seminars

• Choctaw Fair booth focusing on diabetes prevention

• Cooking demonstrations

• 10,000-step program

• Water aerobics

• Community walks

• Fitness Day

• Fishing rodeos

• Bike rodeos

• Pool parties

• Basketball tournaments

• World Diabetes Day

• Fitness education

• Diabetes education

• Home run derby

• Exercise classes

• Intensive fitness classes

• Bingo nights

• Annual Unity/Spring Walk

Willis also described the I Care Team, which was established in 2010 to provide integrated services for diabetes patients. The team includes expertise in dentistry, diabetes management, women’s wellness, diabetes education, exercise, nutrition, and community health. One day each month it sponsors a Diabetes Wellness Day, in which patients can attend a “one-

stop shop” for the services they need. Patients receive vision checks, foot exams, flu shots, exercise education, and any other services they might need.

The Choctaw Health Department has established a partnership with Vanderbilt University with funding from the Native American Research Center for Health and under the guidance of an advisory council drawn from tribal leaders. The goals of the partnership are to identify challenges in diabetes management and develop computer, cell phone, and Internet tools to improve diabetes care and management in Choctaw communities.

The Choctaw Tribal Government believes in unity, Willis concluded. Government departments work collaboratively on projects to provide better service to the Choctaw people. “Unity is our best practice,” she said.

“Unity is our best practice.” —Darlene Willis

The Lifestyle Balance Program of the SouthEast Alaska Regional Health Consortium serves the communities of Juneau, Sitka, and Kake, Alaska. Under a grant funded by the Special Diabetes Program for Indians since 2004, the consortium has been serving people with higher-than-normal blood glucose levels or with a diagnosis of pre-diabetes who are willing to participate voluntarily in 16 weeks of classes. Participants are free to withdraw from the program, but “we hope that they don’t,” said the program’s Walleen Whitson. To encourage participation, program staff members “work on building those relationships, knowing their first name, their husband’s name, their pet’s names, what they do around town,” Whitson said.

Two sessions of weekly classes are offered each year. The program staff is very flexible and will work around the schedules of people who choose to participate. Participants receive a healthy snack and recipe card for a healthy meal at each class, including recipes for healthier versions of traditional foods. They also receive incentives related to the lessons.

Recruitment to the program has come in part by building good working relationships with health care providers. The program keeps providers in the loop as it works with participants, and it stays involved in the community by partnering with community organizations. Funding is limited, but the program is fortunate to receive its lab and outpatient services directly from SEARHC.

Retention is critical, said Whitson. The program stays involved with patients by providing quarterly activities based on their ideas, offering coaching during and after completion of classes, and honoring their partici-

pation with rewards. “Hopefully they stay because they want to continue their journey of health and be around to play with their grandchildren and watch their daughter go down that aisle,” she explained.

A focus group made up of program participants arrived at the mission statement “bringing back the way of life.” The program brings traditional foods and activities, such as berry gathering and fishing, into the classroom whenever possible and accommodates seasonal subsistence activities. It helps to support healthy traditional lifestyles and tries to give participants part-ownership of the program so that they feel invested in it.

Whitson showed photographs of two participants, one who had lost more than 100 pounds and one who had lost more than 80. “Look at the smile,” she said. “The smile tells the story.”

“Hopefully they stay because they want to continue their journey of health and be around to play with their grandchildren and watch their daughter go down that aisle.” —Walleen Whitson

DIABETES PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT AMONG PACIFIC ISLANDERS

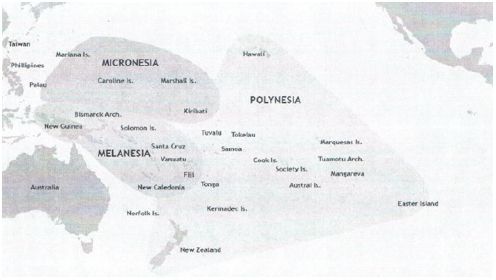

The islands of the Pacific Ocean cover an area three times the size of the continental United States, observed Nia Aitaoto, University of Iowa College of Public Health (see Figure 5-1). Providing services for these islands is like coaching a football team where the players do not all speak the same language, and under these less than desirable circumstances, is going to play in the Super Bowl, Aitaoto remarked.

The European countries that colonized the Pacific Islands introduced clinics and institutionalized medicine to the people already living there. But the islanders already had traditional ways of healing and seeking health. Today, indigenous languages refer to hospitals as “houses of illness.” “You never say the hospital is for you to go and get well. When you get sick, you go over there,” Aitaoto explained. In the process of establishing institutionalized medicine, colonization transferred responsibility for health from individuals to a place.

Today, chronic diseases are the greatest threat to Pacific Islanders, but hospitals are focused on acute illnesses. Although the prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 8 percent in 2007, it was 39 percent in Palau and 47 percent in American Samoa (Hosey et al., 2009). This rate represents a significant shift since the 1940s, when a U.S. government survey found that

FIGURE 5-1 The Pacific Islands cover an area three times the size of the continental United States.

SOURCE: Wikipedia (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacific_Islands [accessed January 7, 2013]).

Pacific Islanders suffered from diseases such as tuberculosis and yaws but had no malnutrition, obesity, or diabetes.

Pacific Islanders face serious economic as well as health struggles. More than 60 percent of residents of Palau and American Samoa, and more than 90 percent of residents of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), are under the federal poverty line. In 2006, per capita spending for health care in the United States was $5,711, whereas in Palau it was $791, in the Marshall Islands it was $471, and in FSM it was $270. “What does $270 pay in health care for you? It is not a pretty picture, but if you want to come and see, it is about a $3,000 United Airlines round trip,” Aitaoto said.

Pacific Islanders have always engaged in research, which Aitaoto described with the Samoan phrase Tofa Sa’ili. Tofa means wisdom, while Sa’ili means to search. Tofa Sa’ili, she said, “is man reaching out for wisdom, knowledge, prudence, insight, and judgment through reflection, meditation, prayer, dialogue, experiment, practice, performance, and observance.” Patients seek new knowledge just as researchers do, but not in the pages of JAMA.

Aitaoto also described three forms of wisdom, which she referred to as Tofa Loloto, Tofa Manino, and Tofa Mamao. Using fishing as an analogy, she explained that Tofa Loloto is the fisherman’s perspective from the boat, looking down into the water and figuring out how to catch a fish. Tofa Manino is the land crew on shore who buy fish and support the fisherman.

Tofa Mamao is the person on the mountaintop scanning the horizon for storms to warn the fisherman of danger. “Three different visions. We all need to go get the fish,” she explained.

From a holistic health approach, the near-term perspective involves the mind, body, and spirit. Aitaoto has been involved in research that asked Pacific Islanders about the causes of diabetes, and she and her colleagues have identified four broad types of discourse. The first is that diabetes is caused by behaviors. This view generates shame and lack of support for change, which results in no action being taken. The second is that diabetes is caused by God’s will and not by behavior, which also leads to no action being taken. The third is that it is a Pacific disease caused by a spirit, by wrong actions, or by magic. This belief can lead to action involving traditional healers. The fourth is that diabetes is the result of God’s will but is also caused by disobedience or some other behavior. This belief can lead to repentance and, with proper support, action.

The challenge for health care providers is that diabetes beliefs contribute to two options that lead to inaction, another option that leads to largely traditional medicine, and only one option that leads to action and compliance. An additional complication is that fad medicines can be popular because they seem to be “natural,” rather than based in Western medicine. Even when patients go to Western doctors, they are unlikely to keep going after their pain goes away. “And if they do not get healed, they stop going anyway. It is darned if you do and darned if you don’t,” Aitaoto said.

For many Pacific Islanders, health is not the ultimate goal, said Aitaoto. Health is a means to reach the goal that God gives a person. Also, a person’s spirit has many parts, including shame, fear, forgiveness, and repentance, and Western medicine does not address these aspects of the spirit.

Motivating Pacific Islanders to adopt healthier lifestyles requires looking outside the medical paradigm. It requires support from the family and community. It requires Tofa Manino and Tofa Mamao, not just Tofa Loloto.

In a project in Chuuk State in FSM called the Pacific Diabetes Education Program, participants identified their own needs and concerns. Program organizers took this information and organized educational materials and specific initiatives. For example, the program engaged with women in villages and churches to promote better foot care to reduce levels of lower-extremity amputations, which are more than three times higher in Chuuk State than in the United States. Over the course of the program, amputations decreased by 56 percent.

An important lesson Aitaoto derived from this experience was to make educational materials more local. Materials should use photographs of local people and use the local language. Brochures should be culturally sensitive and relevant to the culture. They should include local foods that are healthy

(such as fish and poi), show physical activities that attract local people (such as hula, surfing, and paddling), and engage the emotions. They should be pretested before use and evaluated after use to ensure their appropriateness at the local level.

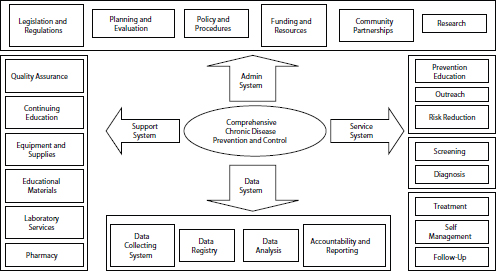

From the perspective of Tofa Mamao, policies, systems, and environments affect the communities in which programs operate. A comprehensive survey of chronic disease prevention and control in the Pacific Islands revealed administrative, service, data, and support systems that all affect outcomes (see Figure 5-2). Systems themselves have cultures, said Aitaoto. For example, if one person in a Pacific Islander team does not absorb a necessary lesson, the entire team is often retrained to avoid shaming the person who did not keep up. Similarly, some people will do the opposite of what a government-led program urges, just to spite the program. In the Pacific, people often engage in feasts that involve huge meals. They are not likely to follow government admonitions not to overeat, but religious leaders have had some success in changing traditional feasting patterns. “When you look at policy, look at culture and policy,” urged Aitaoto.

The Pacific Diabetes Today program started in 1998 with 11 community assessments, followed by planning and implementation. Even after the initial funding for the program ended, 9 of the 11 communities continued doing diabetes coalition work.

FIGURE 5-2 A comprehensive system for chronic disease prevention and control encompasses administration, support, service, and data components.

SOURCE: Aitaoto presentation.

Aitaoto closed her presentation with the words Tofa Soifua, which is a blessing for wisdom and health.

“When you look at policy, look at culture and policy.” —Nia Aitaoto

In response to a question from Newell McElwee, executive director of U.S. outcomes research for Merck & Co., Inc., about whether community based programs such as the programs described by the speakers are scalable and sustainable, Aitaoto pointed to the Pacific Diabetes Today programs that continued to operate after funding ended. The reason these programs were sustainable is that the community worked hard and got buy-in, she said, adding that “if you get your community’s backing … and stand together with one voice, you can go a long way.”

Whitson said that the Lifestyle Balance Program of the Special Diabetes Program for Indians has been developing a dissemination toolkit to be ready for use when funding ends. The toolkit is designed to enable a community to open the kit and get a program up and running quickly.

Jennie Joe, University of Arizona College of Medicine, observed that one of the most significant steps in diabetes prevention and management in recent years is Congress’s decision to provide special funding to address diabetes because of the magnitude of the problem. Most communities were able to develop the types of interventions that worked in those communities. However, “food and culture are so intertwined that you cannot talk about changing lifestyle or the kind of food that people eat without putting a knife into that sacred spot called culture,” she noted. Hard thinking is needed to devise a program that is workable.

With type 2 diabetes appearing in children as young as 8, Joe is running a camp for children to teach them about diabetes and to get to know other kids who have similar problems. “Some of them become very angry. Some of them are even suicidal … because they feel like they are so different,” she explained. The problem is so pervasive that solutions need to start with the very young.

Maresca said that in urban areas like Seattle, Native people do not live in close proximity, so communities need to be created. People come from multiple counties and have affiliations with different tribes. Community events, such as prevention pow wows, can bring people together

to build trust, relationships, and cultural connections while also educating the community.

Ralph Forquera, Seattle Indian Public Health Board, said that the medical model for diabetes intervention and treatment works relatively well, but collective approaches to health intervention remain difficult. Many prevention programs are geared around the idea of using the community to provide support. People who see each other every day can create reinforcing mechanisms to support an idea. But this sense of community is not as easy to create in an urban environment. Forquera’s organization serves 4,000 to 5,000 Indian people per year, but 44,000 Indians live in King County alone. Because his program has no contact with the rest of the Native population, there is no way to know about their health status or to advocate for more resources. In general, the IHS is funded at less than half of need. But only about 1.9 million of the 5.1 million (just over one-third) of the Indian people in the country are served. “It is the community piece that is the biggest struggle for us to try to resolve,” Forquera said.

Willis suggested that individuals from different communities are needed who have the emotional commitment to find Native peoples and teach them. Members from different tribes need to teach people how to live in a healthy way.

Ira SenGupta, executive director of the Cross Cultural Health Care Program, spoke about work her program did with a small grant from the vitamin settlement1 on diabetes and chronic disease prevention in local Seattle area Asian-Pacific Islander communities. One program emphasized hula, not just as a form of exercise but also because members of the community enjoyed that activity. The program also taught children in after-school programs about good nutrition and exercise; the children then were able to take this information back to their parents and grandparents.

Kerri Lopez, Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board, said that part of her job is to examine the standards of care that tribes submit annually,2 and “we are not doing very good.” Accountability has been increasing, but not all achievements can be measured in quantitative terms or according to best practices. With funding about to run out, said Lopez, “I encourage you all to go call your congressman and your legislatures and say support the Special Diabetes Program for Indians, because our funding runs out in exactly 1 year. If we lose all these programs, it will be devastating to our communities.”

______________

1 In 2000, six vitamin companies were fined for illegally conspiring to raise the price of vitamins. The settlement funding in Washington state was used to fund grants for programs benefitting and improving the health and nutrition of Washington consumers.

2Indian Health Service Standards of Care for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes.

This page intentionally left blank.