Identifying and Addressing the

Needs of Adolescents and

Young Adults with Cancer

A LIVESTRONG and Institute of Medicine Workshop

Cancer is the leading disease-related cause of death in adolescents and young adults (AYAs). Each year almost 70,000 AYAs between the ages of 15 and 39 are diagnosed with cancer, approximately eight times more than children under age 15. This population faces many short- and long-term health and psychosocial issues, such as difficulty reentering school, the workforce, or the dating scene; problems with infertility; cardiac, pulmonary, or other treatment repercussions; and secondary malignancies. Survivors of AYA cancers are also at increased risk for psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicide. In addition, they may have difficulty acquiring health insurance and paying for needed care.

Many programs for cancer treatment, survivorship care, and psychosocial support do not focus on the specific needs and risks of AYA cancer patients. Recognizing this health disparity, in 2006 the National Cancer Institute (NCI) appointed a progress review group (PRG) to produce a report outlining recommendations for improving the care and outcomes for adolescents and young adults with cancer (HHS and LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance, 2006). A plan outlining strategies for implementation of these recommendations was developed in 2007 (LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance, 2007). Since that time, progress has been made in bringing attention to the special needs of AYAs with cancer. However, many challenges remain in providing optimal care for this population.

To facilitate discussion about gaps and challenges in caring for AYA cancer patients and potential strategies and actions to improve the quality of their care, the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) National Cancer Policy Forum (NCPF) collaborated with the LIVESTRONG Foundation to convene a workshop, Addressing the Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer, on July 15–16, 2013, in Washington, DC.1 The workshop featured discussion panels as well as invited presentations from clinicians, researchers, AYA cancer survivors, and health advocates working to improve the care and outcomes for this population. Participants discussed a variety of topics important to AYA patients with cancer, including

• the ways in which cancers affecting AYAs differ from cancers in other age groups and what that implies about the best treatments for AYA cancer patients;

• the unique psychosocial needs of AYA cancer patients;

• behavioral health and lifestyle management;

• fertility preservation;

• adequate cancer screening and surveillance for AYA cancer patients;

• challenges in acquiring health insurance and paying for appropriate treatment and survivorship care;

• long-term medical and psychosocial needs for AYA cancer survivors;

• palliative care; and

• end-of-life care needs.

Participants also discussed research gaps and the challenges to developing an evidence base to guide the care of AYAs with cancer. Because of the dearth of data on the AYA population, a number of speakers presented data from studies of childhood cancer survivors who have since entered the AYA age range. Although it may be reasonable to extrapolate some findings from that data to patients diagnosed as AYAs, caution is needed in drawing

________________

1 This workshop was organized by an independent planning committee whose role was limited to the identification of topics and speakers. This workshop summary was prepared by the rapporteurs as a factual summary of the presentations and discussions that took place at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants; are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine, the National Cancer Policy Forum, or the LIVESTRONG Foundation; and should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

conclusions for the AYA population. Workshop participants also suggested policy strategies that could be pursued to improve the care of and outcomes for this population.

This report is a summary of the workshop. A summary of suggestions from individual participants is provided in Box 1. The workshop agenda and statement of task can be found in the Appendix. The speakers’ biographies and presentations (as PDF and audio files) have been archived at http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Disease/NCPF/2013-JUL-15.aspx.

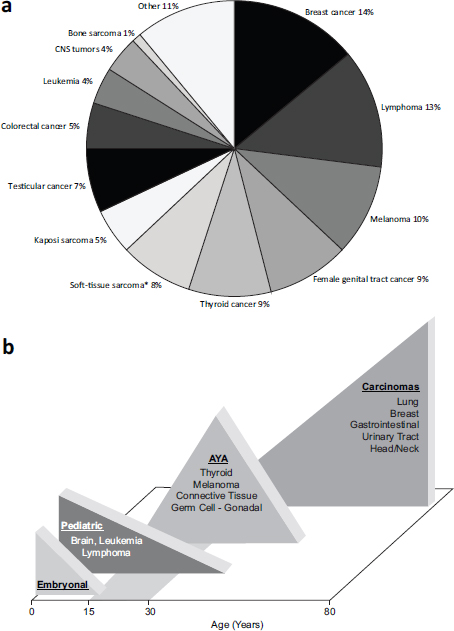

Adolescents and young adults are more susceptible to certain types of cancers, including leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma, and cancers of the central nervous system, germ cells, connective tissue, and thyroid. This group of cancers differs from the cancers that commonly afflict children or older adults. Consequently, “pediatric oncologists and adult-treating physicians and medical oncologists are not as familiar with this group of cancers as they are with the other cancers that affect their patients,” said Archie Bleyer, clinical research professor at the Knight Cancer Institute of the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) (see Figure 1). Brandon Hayes-Lattin, associate professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology and the medical director of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program at OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, said that AYAs are also more likely to be diagnosed with different subtypes of cancers than other groups, which affects what treatments are most likely to be effective for them. For example, one study found that AYAs are more likely to be diagnosed with melanomas that have BRAF2 mutations and thus are more likely to respond to BRAF inhibitor drugs (Menzies et al., 2012). Similarly, AYAs diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) tend to have genetic defects in their tumors that are associated with better prognosis. “This might explain why younger people, even if given the same therapy [as older adults] tend to do better,” he said. However, he also presented data showing that AYA patients who received a pediatric treatment regimen for ALL had a 63 percent event-free survival at 7 years versus 34 percent with the adult treatment regimen (Stock et al., 2008). He added that a recent meta analysis found that patients under the age of 35 with a matched sibling had significantly better survival with an allogeneic bone marrow transplant (Gupta et al., 2013).

________________

2 Human homolog B of v-raf (rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma viral oncogene).

BOX 1

Suggestions Made by Individual Workshop Participants

Address the care needs of Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) patients diagnosed with cancer

• Provide a clearinghouse for programs focused on AYA patients with cancer

• Implement care models that promote timely referral, timely initiation of treatment, and attention to treatment-protocol adherence

• Establish multidisciplinary care teams with training in the unique needs and developmental stages of AYA patients

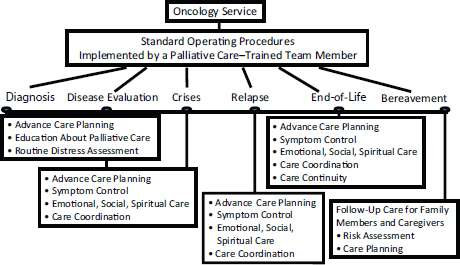

• Integrate information about palliative care into new patient orientation packets and programs and incorporate proactive palliative care across the cancer care continuum

• Discuss fertility at the time of diagnosis and have in place an established referral mechanism for fertility preservation

• Design stress-management programs for cancer patients

• Design lifestyle intervention programs to match the developmental stage and interests of AYA patients

• Provide guidance on how to maintain effective access to health care and insurance, including follow-up cancer care, survivorship care, and routine primary care

Improve cancer survivorship care for AYA patients

• Develop new models for transitioning AYAs into survivorship care and provide tiered care to AYA cancer survivors based on their particular long-term risks and psychosocial needs

• Develop evidence-based guidelines for surveillance of cancer recurrence and screening for new cancers

Bleyer noted that the incidence of melanoma, cervical cancer, and lung cancer has declined among AYAs during the past 10 years, probably due to prevention efforts, including anti-smoking and pro-sunscreen campaigns, restrictions on indoor tanning devices, and use of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. Bleyer said that although the incidence of most of the cancers that AYAs are prone to develop has declined or has not increased in the past 10 years, some types of cancer have become more common in this age group, including kidney, thyroid, breast, colorectal, and testicular

• Use an exposure-based approach to risk-reduction strategies for late effects and secondary cancers among AYA cancer survivors

• Increase efforts to identify patients with genetic syndromes that predispose AYAs to cancer and to implement evidence-based risk-reduction strategies for those patients

• Foster more collaboration between oncologists and primary care providers

• Consider fertility preservation post treatment if desired

Improve training, education, and research

• Provide more specialty training programs and fellowships and continuing medical education programs focused on the care of AYA patients and establish standards for training

• Address research gaps in psychosocial care, late treatment effects, fertility, lifestyle interventions, access to care, and socioeconomic consequences of cancer diagnosis (such as education, employment, and career)

• Measure patient outcomes following psychosocial care to ensure that care is informed by evidence

• Foster more collaboration among various organizations, institutions, and federal agencies

• Educate the AYA population about new options to obtain and maintain health insurance through the Affordable Care Act (ACA)

• Use existing data to better understand the patterns of health care utilization and unique burdens of AYA cancer survivors, particularly in relation to the impact of the ACA

• Develop and leverage online resources to communicate with AYA patients and to facilitate research

• Tailor communications about research for the AYA population

cancer and ALL. He said that the increase in colorectal cancer incidence might be due to an increase in HPV-associated rectal cancer combined with an increased likelihood of detection now that colonoscopies are being applied more widely.

He added that although the incidence of both kidney and thyroid cancer has substantially increased among AYAs, this is likely due to increased detection by ultrasound and other diagnostic imaging. “Both are examples of overdiagnosis in which our diagnostic testing has become so advanced

FIGURE 1 (A) Relative frequency of the common types of cancers in adolescents and young adults, aged 15–39, 1992–2002, and (B) the prevalence of cancer histology by age. The cancers that peak in incidence within each age range are listed in each triangle.

*Excluding Kaposi sarcoma.

NOTE: AYA = adolescent and young adult; CNS = central nervous system.

SOURCES: (A) Bleyer presentation; Bleyer et al. (2008). Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Reviews Cancer (Bleyer et al., 2008), copyright 2008. (B) Hudson presentation; Bleyer et al. (2006).

and widely available that we are now detecting indolent lesions of epithelial origin (IDLE) that do not need to be fixed. We are diagnosing more than we need to, and we are subsequently overtreating,” Bleyer said.

A new finding of uncertain significance is the proportion of cancer in AYAs that is not considered malignant, such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast and low-grade brain tumors (gliomas, craniopharyngioma, meningioma). Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program indicate that about 15 percent of AYA cancers—one in every six to seven patients—are reported as non-malignant, the highest proportion of all age groups. Some of these non-malignant cancers are nonetheless lethal. “We need to look into this problem,” Bleyer said.

Melissa Hudson, director of cancer survivorship and division coleader for the cancer prevention and control program at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, showed that survival improved for those diagnosed with cancer in their 20s in the period 1993–1998 compared to those diagnosed during 1975–1980 (Veal et al., 2010). Survival decreased during the same time span for those diagnosed in their 30s.

More recent trends in cancer incidence, survival, and mortality among AYA patients are currently being assessed. The NCI held a meeting in September 2013, to examine current science and research gaps in AYA oncology. The workshop utilized five working groups that reviewed the available data on the epidemiology (incidence, survival, mortality) of select AYA cancers, as well as evidence related to basic biology, clinical trial enrollment, models of care, and health-related quality of life/symptom management for this population.

PROGRESS SINCE THE NCI PROGRESS REVIEW GROUP REPORT AND IMPLEMENTATION PLAN

The NCI PRG report made recommendations in five broad categories, shown in Box 2. The LIVESTRONG Foundation then convened the LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance, which has since evolved into an independent organization called Critical Mass: The Young Adult Cancer Alliance, to implement the report. Hayes-Lattin reported on the progress that has been made since the report came out in 2006.

BOX 2

NCI Progress Review Group Recommendations

1. Identify the characteristics that distinguish the unique cancer burden in the AYA oncology patient.

2. Provide education, training, and communication to improve awareness, prevention, access, and high-quality cancer care for AYAs.

3. Create the tools to study the AYA cancer problem.

4. Ensure excellence in service delivery across the cancer control continuum.

5. Strengthen and promote advocacy and support of the AYA cancer patient.

SOURCES: Hayes-Lattin presentation; HHS and LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance, 2006.

Identifying the Unique Cancer Burden in the AYA Population

A number of retrospective analyses have provided evidence for the biological distinctiveness of some of the cancers diagnoses in AYA patients, including osteosarcoma, colorectal cancer, ALL, breast cancer, testicular cancer, and thyroid cancer (Tricoli et al., 2011). Reports have also documented the unique characteristics of AYAs with cancer, including characteristics related to health-related quality of life (Smith et al., 2013), epidemiology trends (Johnson et al., 2013), toxicity (Gupta et al., 2012), and AYAs’ experience of psychological distress (Kwak et al., 2013).

Education, Training, and Communication

Efforts have been made to raise awareness of AYA cancer issues as a first step toward increasing the national focus on and resource allocation to the AYA cancer problem. The LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance has provided targeted education to patients, families and caregivers, and the public about AYA cancer issues and fostered the education of multidisciplinary care providers who work with AYAs in order to improve referrals and services for this population. Professional educational programs focused on AYAs with cancer now include the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s

Focus Under Forty3 online curriculum and the nurse oncology education program At the Crossroads.4 In addition, the LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance published a position statement on the necessary components for AYA oncology training for health professionals (Hayes-Lattin et al., 2010). There also now is a National Young Adult Cancer Awareness Week and associated media outreach activities.

“The field,” Hayes-Lattin said, “really is at a turning point of evolving from the notion of raising awareness as the principal target to formalizing some of those components, whether that would be requirements in educational curricula or certification standards.”

The NCI PRG report made a number of recommendations regarding research tool development, including recommendations to create a large prospective database of AYA cancer patients to facilitate research on this age group, to increase the number of annotated patient specimens to support research progress, and to improve grant coding and search term standardization to enable the evaluation of research efforts and progress. Since the report came out, there have been improved search tools in PubMed and other research databases that enable targeting of AYA-specific studies. But Hayes-Lattin noted a lack of available annotated biological specimens from AYA patients that researchers can prospectively link to treatments and patient outcomes. There is also still a need for a large prospective database of AYA cancer patients to facilitate research on this age group.

Much work remains to be done in this arena, Hayes-Lattin stressed, but he did point to progress made in other research-related areas. Efforts have been made to amend clinical trial eligibility requirements relating to age so that more adolescents and young adults with cancer can participate. A treatment regimen based on a pediatric protocol was recently applied in a clinical trial setting across multiple adult cooperative trial groups.5 The Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology also funded an adolescent and young adult cohort study that showed the feasibility of prospectively following adolescents and young adults from the time of their cancer diagnosis. Hayes-

________________

3 See http://university.asco.org/focus-under-forty (accessed October 8, 2013).

4 See http://www.noep.org/nursing-cne/preview/40-at-the-crossroads-cancer-in-ages-15-39 (accessed October 8, 2013).

5 See http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00558519 (accessed October 8, 2013).

Lattin also noted the newly created AYA-specific committees that are now a part of the NCI-supported National Clinical Trials Network. He called on the NCI and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to formalize and coordinate their internal efforts to study AYAs with cancer.

To improve the standards and quality of cancer care provided to AYAs, the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology published a position statement on elements of such quality cancer care (Zebrack et al., 2010). In addition, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recently published its recommended guidelines for the care of AYAs. There have also been efforts to recognize and support excellence in service delivery, including the Fertile Hope Centers of Excellence Program, which recognizes fertility preservation efforts. But there is a lack of coordination among these efforts, Hayes-Lattin stressed. There also is still a great need to define outcome measures of high-quality care for AYA patients and then study how the various models for AYA care are or are not facilitating those outcomes, he added.

Both the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology and Critical Mass continue to expand their AYA work and to hold annual meetings aimed at fostering advocacy and support for AYAs with cancer. There have also been efforts among other medical and advocacy organizations, including a number of charities that have combined forces to develop the International Charter of Rights for Young People with Cancer.6

“Since 2006,” Hayes-Lattin said, “we have amassed a really impressive array of medical institutions and advocacy groups that focus on at least some components of the adolescent and young adult cancer issue. The next opportunity is for us to map in a detailed way what that network looks like to increase the reach of organizations that have a part and to also find what gaps exist.” Hayes-Lattin added that Critical Mass is currently attempting to fill that mapping and coordination role.

________________

6 See http://cancercharter.org (accessed October 8, 2013).

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF AYA CANCER DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

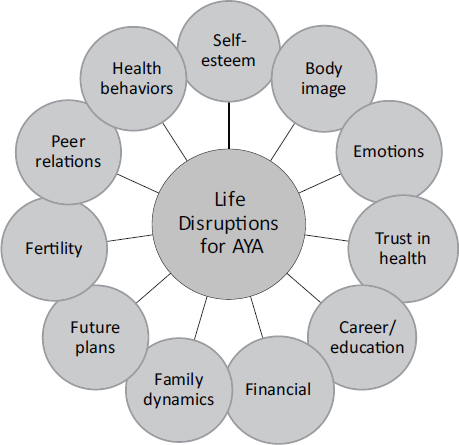

As several speakers pointed out, young adults are at a unique stage in their emotional, cognitive, and social development, which cancer often disrupts. The attempts by these young adults to establish independence from their parents, to complete school, to enter the workforce with a desired career, to find a life partner, and to raise a family often are temporarily, or sometimes permanently, derailed (see Figure 2).

Bradley Zebrack, associate professor at the University of Michigan School of Social Work, said that a young person’s experience with cancer is often the first time that he or she has confronted mortality in general. “Many of them have not even experienced a grandparent who has died or

FIGURE 2 Possible life disruptions for AYA patients with cancer.

SOURCE: Fasciano presentation.

have been to a funeral,” he said. “These challenges to mortality come totally out of the blue, and they have limited experience in how to cope with these issues.”

Karen Fasciano, a clinical psychologist at the Harvard Medical School and director of the Young Adult Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said that it is often the case that the demands of the young adults’ life-cycle stages go directly counter to the demands of their illness:

• When they want more intimacy with their peers and independence from their parents, and they want to feel like they are in control and invulnerable, the demands of their cancer make them feel isolated, vulnerable, dependent, and uncertain.

• When they want to feel part of a peer group and fit in, they feel isolated by the uniqueness of what they are experiencing.

• When they are developing their sexual identity, cancer treatment can influence sexual health and feelings of attractiveness.

• During a period focused on development of executive functions (i.e., planning, organization, mental flexibility, reasoning skills), cancer treatment can disrupt this development, and can impact educational and vocational attainment as well as decision making.

• When they are trying to make future plans, the future can seem elusive.

“Young people are really challenged with balancing the demands of illness with the demands of the life cycle,” Fasciano said, “and there can be some regression in development.” But she made a point of quoting a young adult cancer patient who gave this advice to fellow patients: “Don’t compare the beginning of your journey to the middle of someone else’s, and don’t feel like you are behind on anything or set back, because you haven’t taken a step back. You have moved onto a different path. Your life is different now.”

Patricia Ganz, Distinguished University Professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health and the David Geffen School of Medicine, and director of cancer prevention and control research at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, stressed that young cancer survivors vary as to what their psychosocial needs are and that it is important to assess this in every patient rather than to treat the patients in cookbook fashion based on age assumptions.

Several participants pointed out that cancer disrupts family dynamics for AYAs. Often, a newly independent young adult may return home to live with his or her parents during cancer treatment. Although family support and cohesiveness is important in the adjustment to a cancer diagnosis and the associated life disruptions, Fasciano said, the different perspectives and expectations that family members can have may contribute to some distress. Many younger AYA patients may depend on parents for decision making, but for patients over 18 years of age, issues regarding guardianship and/or legal decision making may arise. Providers can help AYA patients and their families determine the role of the family in the patient’s care. “Providers can assess and help them define who is responsible for their care and discuss the responsibility of the family,” she said.

Zebrack said that not only are AYAs often concerned about parents being overprotective of them, but they may also be overprotective of their parents. “Maybe they have moved to completely different cities and go through the experience of cancer therapy on their own because they do not want to call Mom and Dad who are three time zones away and get them worried about it,” he said.

For AYA patients who already have children of their own, a cancer diagnosis and the burdens of treatment can be very disruptive to their family life and psychologically challenging for their children.

Disruption of School, Work, or Career Plans

Ruth Rechis, vice president of programs at the LIVESTRONG Foundation, described the results from an online survey7 conducted by LIVESTRONG in 2012, which found that most participants had to make some changes in their work life following a cancer diagnosis. Those changes

________________

7 Each of the surveys presented has strengths and limitations for assessing the experience of AYA patients with cancer, and each provides information on a different subset of the AYA population. For example, in the studies using large population based data (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and Behavioral Risk Factors and Surveillance System), survivors were defined as those with a history of cancer diagnosed at ages 15~$@~8211;39 and the majority were longer-term cancer survivors. Other studies focused on individuals who are currently ages 15~$@~8211;39, and were recently diagnosed (including some with poorer prognosis and less likely to become longer-term cancer survivors). This is particularly relevant when considering differences in study results.

included taking time off, switching from full-time to part-time work, and changing to a less demanding job or to one with a more flexible work schedule. About three-quarters of the respondents also reported that their ability to perform mental or physical tasks and their overall productivity at work were affected by their cancer diagnosis. The percentage of respondents who reported these effects on their work was greater among AYA cancer survivors than among other cancer survivors.

In the same survey, more than one-quarter of respondents reported leaving school, about one-third reported that they had difficulty keeping up with school work, and a nearly equal number reported missing a large amount of school. Fifteen percent did not have any special services while they were in school, and many reported feeling that their classmates and teachers did not know how to support them.

The Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) Study focused more on what happened to AYA cancer survivors once they completed treatment (Parsons et al., 2012). This study surveyed AYAs who were in school or working when they were diagnosed with cancer and assessed how many were able to return to school or work between 15 and 35 months post diagnosis. The survey found that although most respondents felt cancer had an adverse impact on their schooling or work, most were able to resume school or work. Their employment rates were comparable to those of older adults diagnosed with cancer, although slightly less than the employment rates for their age group, reported Helen Parsons, assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics in the School of Medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Those who quit working completely directly after their diagnosis were the least likely to return to work.

Another study based on the Behavioral Risk Factors and Surveillance System (BRFSS) sponsored by CDC compared AYA cancer survivors to same-age peers who had not had cancer (Tai et al., 2012). A significantly lower proportion of AYA cancer survivors reported being employed for wages, and a significantly higher proportion of AYA cancer survivors reported being out of work, said Eric Tai, medical officer for the Comprehensive Cancer Control Branch at CDC.

In addition, a study based on a large national survey, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, evaluated employment and medical expenditures and found that the mean annual lost productivity for survivors of AYA cancers is more than double that of individuals without a cancer history (Guy et al.,

2013). These individuals were more likely to experience greater health-related unemployment and productivity losses, reported Robin Yabroff, an epidemiologist in the Health Services and Economics Branch of the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences at the NCI.

Others reported on what they called “job lock,” or the inability of cancer survivors to pursue a career of choice, often because of the need to keep their jobs and not go back to school in order to maintain employee benefits, including health insurance. “Although the data look good in that a large number of cancer survivors are working,” Ganz said, “they may not be working up to their potential and may have lost opportunities because of their cancer.” Yabroff concurred, adding, “It’s really important to not just think about whether they are currently employed but whether they would have had the same career trajectory if they hadn’t had cancer.”

The open-ended comments section of the AYA HOPE Study revealed a number of psychological stresses experienced by AYAs with cancer, including a fear of recurrence, concerns about managing their own distress and emotions as well as those of their parents and friends, and feeling burdened by the emotional responses of friends and family members when they told them they had cancer. Thirty-five percent of the AYAs indicated some kind of clinically significant distress at some point during the first 12 months after diagnosis. But Zebrack said that some respondents also noted positive life changes following their cancer diagnosis. For example, one person wrote, “It was a devastating experience, but it changed my life. I became more positive, more health conscious. I exercise more. But every day I think about it, and I seem very scared that it may return and I may not be strong enough to fight again.” Zebrack called this “the two faces of the cancer experience—both the elements of desperation and fear, but also of celebration and hope” and said it was reflected in a lot of the comments gathered in the study.

Zebrack described one study that found that the prevalence of psychological distress among AYAs with cancer varied over time following diagnosis (from 6 to 41 percent) but did not vary by the type of cancer or the prognosis (Kwak et al., 2013). The AYA HOPE Study found that 12 months after their cancer diagnoses, 41 percent of AYA cancer survivors reported an unmet need for counseling and other forms of psychosocial support.

AYAs frequently experience isolation along with their cancer diagnosis and treatment. Zebrack reported that the AYA HOPE Study found that many AYAs with cancer talked about their friends no longer calling them or dropping by or reported not having energy for those friends and maintaining their relationships. Sexual relationships are also difficult to maintain if cancer treatment affects an individual’s feelings of attractiveness or leads to sexual dysfunction. One cancer survivor who spoke at the conference said that her surgical scar and lack of hair made it hard for her to socialize. “I was so ashamed, and no one was there to help me figure out how to navigate that,” she said.

Zebrack added that social activity among younger AYAs often involves drinking alcohol, which is problematic for someone undergoing cancer treatment. Dating can be especially challenging, with many young cancer survivors struggling with decisions about when to reveal to potential romantic partners their health histories and how those might impact their long-term survival or ability to have children. “They have a fear of rejection,” Zebrack said. The Childhood Cancer Survivor survey (for those diagnosed between the ages of 0 and 21 years) found that cancer survivors were less likely to be married than their siblings who had never had cancer. Long-term, committed relationships can also be challenged following a cancer diagnosis.

The uniqueness of their cancer experience also can make AYAs feel as if they do not fit into their peer groups, which can contribute to their sense of isolation. As one AYA cancer survivor at the workshop said, “Now, when I go to a bar and people share their stories, they often seem kind of the same to me, and mine is a little different. It makes me stand out.” Another survivor said, “At 25 you are thinking about getting a job and getting married and having kids and buying a house. But when you are 25 and have cancer, you are not thinking about any of that. You are thinking, ‘I’m going to die, and this is going to suck, and how am I going to pay for this, and what am I going to tell my parents?’”

LATE AND LONG-TERM SIDE EFFECTS OF TREATMENT

Studies show that, because of their cancer treatments, many AYA cancer survivors are more likely to develop various chronic health problems than their peers without cancer. Many of these health problems develop

long after treatment has ended (see Table 1). Using data collected by its Behavioral Risk Factor System, the CDC found that, compared to people who have never had cancer, AYA cancer survivors have about double the prevalence of cardiovascular disease and are also at increased risk for diabetes, asthma, and hypertension. Furthermore, the prevalence of disability was twice as high in AYA cancer survivors as among those without cancer. Twenty-four percent of AYA cancer survivors reported having had 14 or more days of poor physical health in the previous month, which was double that seen among people without cancer.

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) found that the age at diagnosis does not predict the degree of health conditions developed by a cancer survivor, reported Kevin Oeffinger, director of the Adult Long-Term Follow-Up Program in the Department of Pediatrics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. This study found that almost half of childhood cancer survivors experience a serious or life-threatening condition or death between 5 and 30 years after diagnosis and that almost three-quarters develop at least one chronic condition (Oeffinger et al., 2006). Another study of adult survivors of childhood cancers found that by age 45, 96 percent of them had developed a chronic health condition and 81 percent had a severe or life-threatening condition, Oeffinger said (Hudson et al., 2013). The risk of developing a health condition increased over time.

Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease are two common late effects of cancer treatment. Compared to healthy controls, survivors of testicular cancer are twice as likely to develop metabolic syndrome, even among those who are still relatively young men, Oeffinger reported. Studies suggest that the increased risk might stem from having received cisplatin and bleomycin chemotherapy, which can damage the lining of blood vessels and start an inflammatory reaction that results in cardiovascular disease. Patients who have had brain tumors also have metabolic disturbances that increase their risk of both cardiac disease and strokes. Cardiac disease risk is also increased in patients who have been treated with anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin. According to Oeffinger, almost all women who undergo total body irradiation prior to a stem cell transplant during adolescence or the young adult years will develop metabolic syndrome and have a higher risk of developing heart disease, despite often being thin. These women often lose their subcutaneous fat but have increased visceral fat.

Bernard Fuemmeler, associate professor of community and family medicine, psychiatry and behavioral science, and psychology and neuroscience at the Duke University Medical Center, also reported on studies that

TABLE 1 Potential Late Effects of Cancer Treatment, by System and Exposure

| System | Exposures | Potential Late Effects |

| Cardiovascular | Radiation therapy | Myocardial infarction or stroke |

| Anthracyclines | Congestive heart failure | |

| Platinums | Valvular disease | |

| Hypertension | ||

| Pulmonary | Radiation therapy | Restrictive lung disease |

| Bleomycin | Pulmonary fibrosis | |

| Carmustine/Lomustine | Exercise intolerance | |

| Renal/urological | Radiation therapy | Renal insufficiency or failure |

| Platinums | Hemorrhagic cystitis | |

| Ifosfamide/Cyclophosphamide | ||

| Endocrine | Radiation therapy | Obesity |

| Alkylating agents |

Infertility and gonadal dysfunction |

|

| Dyslipidemia | ||

| Insulin resistance and diabetes | ||

| Central nervous | Radiation therapy | Learning disabilities |

| system | Intrathecal chemotherapy | Cognitive dysfunction |

| Psychosocial | Cancer diagnosis |

Affective disorders (anxiety, depression) |

| Posttraumatic stress | ||

| Sexual dysfunction | ||

| Relationship problems | ||

|

Employment and educational problems |

||

| Insurance discrimination | ||

|

Adaptation and problem solving |

||

| Second | Radiation therapy | Solid tumors |

| malignancies | Alkylating agents | Leukemia |

| Epipodophyllotoxins | Lymphoma | |

SOURCE: Adapted from Oeffinger presentation.

showed survivors of childhood cancers, especially those with leukemia, or those treated with high-dose radiation, were more likely to be obese (Meacham et al., 2005; Oeffinger et al., 2003; Tai et al., 2012). The CCSS found that having cranial radiation therapy, being diagnosed at a younger age, or being female boosted the risk of developing obesity. One study of children with ALL found that 23 percent were obese by the end of their treatment, compared to 14 percent who were obese at diagnosis (Withycombe et al., 2009). Another study found that male survivors of childhood cancers had body mass indices similar to those of their siblings but that they had greater trunk fat and total body fat (Miller et al., 2010). “These studies cause concern that during that year of treatment, children are not being as active as they usually are and so are losing the opportunity to gain lean muscle mass,” Fuemmeler said. Unfortunately, there are few data regarding these late effects among survivors of AYA cancer.

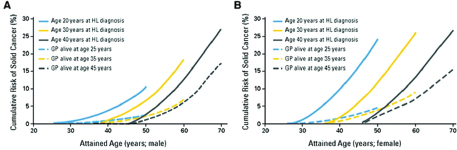

Cancer survivors are also at risk for secondary malignancies (see Table 1). Survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) have a particularly high risk of developing another cancer, Hayes-Lattin said. A study by Hodgson (2011) found that the risk of developing another malignancy increased by more than 1 percent per year (see Figure 3). The risk varied depending on what age the HL diagnosis was made. “Although many of our Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients have little morbidity at the end of their treatment, about 16 percent that we follow have gone on to develop three or more major primary cancers,” Oeffinger said. Because of that, oncologists are now frequently opting to treat HL patients with a chemotherapy that goes by the acronym ABVD (containing adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastin, and dacarbazine) instead of an older chemotherapy regimen called MOPP (containing mustragen, oncovin [aka vincristine], procarbazine, and prednisone) because the former has a reduced risk of morbidity and late effects.

Breast cancer is particularly prevalent among survivors of childhood HL who were treated with chest radiation. One study found that 35 percent of women with HL who received chest radiation developed breast cancer by age 50, compared to 31 percent of women with mutations in the BRCA genes and 4 percent of controls. The younger the women were when they received the radiation therapy and the higher the dose of radiation they received, the more likely they were to develop breast cancer. Risk tapers off in those who were 35 years or older when they received the treatment. The interval between chest radiation and the development of breast cancer is usually between 10 and 20 years. Bilateral breast cancer is also more common in women who received chest radiation. “It is overwhelming how fre-

FIGURE 3 Cumulative incidence of solid cancers among 5-year survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) compared with controls of the same age in the general population (GP).

NOTE: A = males, B = females.

SOURCES: Hayes-Lattin Presentation; Hodgson et al.: Journal of Clinical Oncology 25(12), 2007:1489–1497. Reprinted with permission. © 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

quently we see bilateral disease, and we need to be very proactive with that,” said Oeffinger. He added that survival following a breast cancer diagnosis is linked to the stage of the cancer at diagnosis, just as it would be for someone without a prior cancer diagnosis, and that the hormone receptor status of the breast tumors in HL survivors is similar to that among the general population. By contrast, radiation to the ovaries lowers breast cancer risk, presumably by lowering estrogen exposure.

INFERTILITY AND EFFORTS TO PRESERVE FERTILITY

Now that so many cancers diagnosed in children and AYAs are curable, there has been growing concern about how cancer treatment might affect their fertility and about ways to preserve that fertility. Jennifer Levine, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics and director of the Center for Survivor Wellness in the Division of Pediatric Oncology at Columbia University Medical Center, said that the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have all developed guidelines that state that fertility preservation should be an integral part of cancer treatment for AYAs. One participant said, “I think it has gone from ‘I hope my doctor thinks about my fertility’ to a mandate, and hospitals like mine have policies

in place so they provide information about the risk of infertility and offer potential preservation options.”

The 2010 AYA LIVESTRONG survey found that about one-quarter of AYAs took steps to preserve their fertility before their cancer treatment began. The most common steps taken were sperm banking for men and preserving eggs and embryos for women. Sixty-five percent of males who tried to father a pregnancy after treatment were successful, while 58 percent of females who tried to become pregnant after treatment were successful. The majority of those with successful pregnancies used natural means to become pregnant, Rechis reported.

The survey also assessed the reasons for not using fertility preservation and found that although some people were not interested in having children, many did not know their fertility was at risk, did not have enough time to pursue fertility preservation options, or thought the costs of such preservation were too prohibitive. “These are all things we can affect and make a change for AYA survivors,” Rechis said. Oeffinger agreed and said that there are psychological reasons to preserve fertility. “Infertility is the number one issue of our patient population because it ties into their body image, their sense of self-worth,” he said.

Levine provided some background information on the biology of fertility and then outlined the causes of infertility in cancer patients. In males, the germ cells start maturing into sperm cells at puberty, and in a healthy male, who is generally fertile from puberty until time of death, they continuously self-renew. Cancer treatment can deplete these germ cells. Levine said that it is very common for males to experience a temporary lack of sperm during or after radiation or chemotherapy because of both the destruction of maturing sperm cells and a relative depletion of germ cells. The maturation process can resume post-therapy, and the amount of time that a male is infertile after treatment varies from months to years. Ultimately, males usually become fertile again, but permanent infertility can occur if there is such a sufficient depletion of germ cells that there is no possibility of the maturation process resuming.

Cancer treatment or surgery can also cause infertility by damaging the pituitary gland, the pelvic nerves, or the ductal system, which can interfere with ejaculation. Sometimes it is the cancer itself and not necessarily the treatment that affects male fertility. Men with testicular cancer or HL will

sometimes lack viable sperm prior to treatment because of the effects of the disease process itself, Levine said.

Sperm banking is a well-established means to preserve male fertility. If viable sperm are produced, those sperm are frozen and stored for future use. It is generally recommended that men produce several specimens over the course of a number of days in order to maximize the volume of the sperm that can be stored. But it is possible that just one specimen will be sufficient for future fertility, Levine said. “There often is a lot of pressure to begin therapy, and people feel uncomfortable delaying the start of therapy to allow sperm banking,” she said. “But if sperm banking is thought of at the time of diagnosis, there may be time to produce multiple specimens before treatment starts.”

The cost of sperm banking can be a challenge for some patients. It costs between $500 and $700 to do a semen analysis, and annual storage costs range between $200 and $400. Fertile Hope’s Sharing Hope Program8 enables cancer patients to get discounted rates for sperm banking, Levine said. However, some patients may be too sick or too young to bank sperm at the time of diagnosis, and some may decline due to religious beliefs, she said.

If producing an ejaculate is a problem, sperm can be collected under anesthesia. This outpatient procedure is becoming more common, Levine said. Another option is to remove testicular sperm tissue and freeze it or to freeze an entire testicular specimen that includes germ cells which will be matured at a later point in time. Such testicular extraction can also be attempted post therapy as a more targeted means of acquiring viable sperm for assisted reproduction. In males receiving radiation therapy, gonadal shielding is also a common procedure to help preserve their fertility.

“Almost any post-pubertal male who is willing or interested in sperm banking should do it because it is really not so invasive,” Levine said. The earlier that men bank their sperm the better, she stressed, because even men with a lower risk for infertility might relapse in a period of time in which they are not producing sperm due to their previous therapy, so they won’t be able to bank sperm at that point. Levine said that although many patients may not require sperm banking, for the 10 or 15 percent of men who end up using banked sperm, “that is how they are going to start their biologic family.” She added that men can undergo a semen analysis for viable sperm

________________

8 See http://www.fertilehope.org/financial-assistance/index.cfm (accessed October 8, 2013).

post treatment to aid their decision about whether to continue to pay for sperm storage.

A woman’s fertility can be affected by a number of actions related to cancer treatment. Removing a woman’s ovaries or her uterus will render her infertile. Uterine surgery can cause scar tissue that may prevent implantation of the embryo. And cancer treatments, including treatments that affect the pituitary, can cause infertility by disrupting normal hormonal regulation. Unlike men, women are born with all the eggs they will ever have, and there is no self-renewal of germ cells. At menarche, women start to lose their egg follicles, and by their mid- to late 30s, their fertility begins to decline. By their late 40s or early 50s, most women reach menopause and can no longer become pregnant.

Cancer treatment can cause acute ovarian failure, in which the number of follicles drops down to levels that impede fertility, and it can hasten menopause. Oeffinger presented a study that found that the older a woman is when she is diagnosed with cancer, the more likely it is that she will experience infertility from her cancer treatment (Letourneau et al., 2012). Nearly half of women treated at age 35 for cancer experience infertility. “In our country, with so many women moving the timing of their family to later years, this obviously is quite an important issue,” he said. Cancer treatments lead some women, especially those treated with high-dose alkylating-agent chemotherapy and those who undergo a stem cell transplant, to experience early menopause. Even women who resume menstruation after chemotherapy can experience infertility. Premature menopause can also lead to sexual dysfunction.

Embryo freezing is the most common method for preserving the fertility of women undergoing cancer treatment, Levine said. This technique requires ovarian hyperstimulation in order to create multiple follicles in the ovaries. The follicles are retrieved prior to ovulation and fertilized to create embryos that are then frozen. The older a woman is when she has the procedure, the less likely is it to be successful. Embryo preservation requires a partner or donor sperm, and is very expensive, costing between $10,000 and $15,000, not including implantation costs. Embryo preservation takes a minimum of 2 weeks.

Oocyte cryopreservation is similar to embryo preservation except that it does not require fertilizing the egg and thus does not require a partner

or donor sperm. Last fall, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine deemed that this approach is no longer an experimental procedure. “It really is something that in general we are thinking more about for our patients,” Levine said, but she noted that oocytes are more susceptible to being damaged by the freeze-thaw cycle than embryos, so the success rate for this procedure is somewhat lower than for embryo preservation. It is just as expensive and requires just as much time, she added.

Another option is to remove ovarian strips, freeze them, and reimplant them later or use them for in vitro fertilization. This procedure can be done immediately and it is the only option for pre-pubertal females. But it is controversial because of the concern that cancer cells, particularly leukemia cells, might be reintroduced with the re-implanted tissue. There also is not much experience reported in the literature, with only about a dozen pregnancies known to have resulted from it, Levine said.

Some patients with cervical cancer are now being treated by removing only part of the uterus and cervix, Levine said; it is possible for these women to carry a pregnancy. In patients who receive radiation therapy, the ovaries can be protected with gonadal shielding and ovarian transposition, in which the ovaries are moved outside of the radiation field. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists are also commonly used to try to preserve female fertility, Levine said, although there is very little evidence to support that approach, and some studies suggest it may actually be detrimental to fertility.

Women may also want to consider pursuing similar actions to preserve fertility after their cancer treatment if they are not ready to have children at that time. Although there are tests that could potentially assess a woman’s fertility, these are not yet adequate or fully validated, Levine said. The CCSS generated promising data indicating that survivors are able to become pregnant, although it appeared that they took longer than their sibling controls.

Once a woman has completed her cancer treatment, she can pursue natural, assisted, or surrogate reproduction, although the possibility of a cancer relapse occurring during the pregnancy must be taken into account, as the pregnancy will limit the treatment options and timing. It is also possible that various late effects of treatment, such as cardiovascular or pulmonary impairments, could affect a pregnancy; these, too, must be taken into account. As Levine noted, such impairments can pose problems during pregnancy, when there is increased blood volume, and their presence may indicate the need to be seen by an obstetrician who specializes in high-risk pregnancies.

There are no data to suggest that children of cancer survivors have any increased risk of congenital abnormalities compared to the general population. But cancer survivors might have a genetic disposition to cancer that could be screened for with pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. Such a procedure can identify, for example, embryos that carry a mutated BRCA gene, Levine pointed out.

Levine suggested that providers discuss fertility with AYA patients at the time of their cancer diagnosis and give them a referral to have a more in-depth consultation with a reproductive endocrinologist if they wish. Fertility preservation should also be considered post treatment if it was not considered before treatment. Levine also suggested having an established referral mechanism in place related to fertility preservation. “If someone comes in saying they want a sperm bank, and you do not know where there is one or what kind of specimen jar to give them, fertility preservation is not likely to happen,” she noted.

Insurance Coverage of Fertility Preservation and Treatments

Not all insurance plans will cover the cost of fertility preservation or infertility treatment for cancer patients. One AYA cancer survivor who spoke at the workshop said that such coverage is critical. After her treatment, she said, she stopped menstruating and sought treatment with testosterone pellets, which cost $500 and were not covered by her insurance. Due to a flexible spending program at her job, she was able to pay for the treatment and subsequently started having normal menstrual cycles. “For 5 years,” she said, “I was menopausal and thought I would never have kids, which is a big emotional toll for a female at the age of 25, and if I hadn’t had money to pay for the testosterone treatment, I never would have tried it.”

Levine noted that LIVESTRONG has been encouraging insurance companies to cover the cost of fertility preservation for cancer patients and that the American Medical Association recently stated that insurance companies should cover fertility preservation in cases where the infertility is expected to occur as a result of cancer treatment. In addition, the California legislature recently introduced a bill to require insurance companies to cover fertility preservation. “If coverage can be obtained, this is going to make a tremendous difference for cancer survivors,” she said.

ONCOLOGY CARE ISSUES UNIQUE TO AYAs

As several speakers pointed out, there are a variety of oncology care issues unique to AYAs, including whether the patients should receive care from pediatric or adult oncologists, how they should transition from pediatric care to adult care, and how extensively their families should be involved in their care. There are also unique biological developmental issues that come into play in adolescents with cancer, and Melissa Hudson stressed that these issues must be considered when devising the patients’ treatment and follow-up care plans. She noted that these individuals are experiencing changes in body composition and rapid periods of growth in which their height and weight are increasing. AYAs also have various health behaviors and needs that are different from children or older adults with cancer, such as use of contraceptives, that may affect cancer treatment. “All these factors present to us unique biologic differences that may affect outcomes that should be considered in the evaluation of these patients,” she said.

Depending on age and specific diagnosis, AYA patients with cancer may be treated at either a pediatric cancer center or an adult cancer center, but often, these patients do not clearly fit into either treatment setting. The majority of patients are treated at an adult cancer center. The AYA HOPE Study found that only 2 percent of AYAs surveyed were treated at a pediatric hospital and only 5 percent saw any pediatric specialists. When only AYAs under the age of 25 were considered and those with early-stage male germ cell cancers were excluded from analyses, only one-quarter of the remaining patients saw a pediatric specialist for their cancer, reported Lynn Harlan, epidemiologist in the Health Services and Economics Branch of the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences at the NCI. If care is provided in an adult community oncology practice setting, patients may not have access to specific AYA-focused programs, and care providers may be less knowledgeable about the unique AYA developmental, psychosocial, and treatment needs, as the majority of cancer patients in the United States are over the age of 65.

One study compared Ewing’s sarcoma AYA patients who received the same treatment but in different settings (Albritton et al., 2004; Paulussen et al., 2003). This study found that patients were likely to survive longer if they were treated in a pediatric setting than if they were treated in an adult

setting, Hayes-Lattin reported, although no reasons were given to explain the findings.

Several AYA cancer survivors at the workshop spoke about how they decided whether to seek pediatric or adult care for their cancers. Hollie Farrish was diagnosed with Wilms’ tumor at the age of 25 after submission of pathology samples for a clinical trial revealed that the tumor, originally thought to be a renal cell cancer, had been misdiagnosed. Her oncologist had no experience with Wilms’ tumors but agreed to care for Farrish in consultation with a nearby children’s hospital. The oncologist made slight adjustments to the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) protocol to take into account the fact that children are more resilient than young adults. The treatment was successful, and Farrish said she appreciated the care she received. “I really liked my adult oncologist and wanted to be cared for by someone I trusted and liked rather than getting punted to a children’s oncologist at the age of 25.” She added, however, that neither a pediatric nor an adult oncology setting was quite appropriate for her. “It was either Dora the Explorer or AARP Travel and Leisure in the waiting room,” she said. “At 25, you are trying to go to Key West for spring break; you don’t want to be going for chemo at Children’s Hospital.” Benjamin Rubenstein, another AYA cancer survivor, decided to continue in the care of the pediatric oncologist who had started treating him when he was 16 because he trusted her and wanted to continue their relationship. “I am very loyal to my doctor because she understands all the treatment we did that affects me in so many different ways. I am going to stick with her until I get tired of playing with puzzles in the waiting room. I may be the first 50-year-old to still be in a pediatric center,” he said.

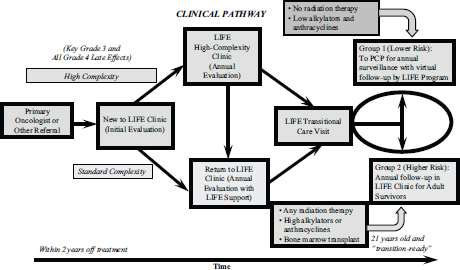

David Freyer, director of the Long-Term Information, Follow-Up and Evaluation (LIFE) Cancer Survivorship and Transition Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) and professor of clinical pediatrics in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, explained that the transition from pediatric to adult care is especially critical for AYA cancer survivors because not only do they need to have more developmentally appropriate care, but they also need extensive follow-up and cancer surveillance by a physician who is aware of the likely chronic conditions and other late effects they are likely to develop from treatment and the risk-based monitoring they need to have.

Unfortunately, studies suggest that this transition is not as seamless as it should be and that many AYA cancer survivors are not receiving adequate follow-up care. The CCSS found that although most respondents had had a general exam within the previous 2 years, less than half had had a cancer-related visit, and 30 percent or less had had a visit at a cancer center (Oeffinger et al., 2004). Another study of the same survivors found that only 14 percent were undergoing general survivorship assessments and only 18 percent were getting the recommended risk-based assessments (Nathan et al., 2008). In addition, in a subpopulation of patients at risk for cardiomyopathy because of anthracycline exposure, within the previous 2 years only 28 percent had had echocardiograms. Only 41 percent of the women at risk for breast cancer had had mammograms.

Freyer listed a number of barriers to health care transitions for patients, providers, family members, and health care systems. Focus groups and small studies find that these survivors often do not seek out appropriate followup, in part due to their geographic mobility or to being unaware of what care is needed. One barrier often cited by these patients, Freyer said, is that they do not know their new providers and do not have a relationship with them as they did with the pediatric oncologists who initially treated them. Parents of adolescent cancer survivors tend to be overprotective and are used to navigating their children’s health care. These family caregivers may also be hesitant to have their children switch to new providers with whom they do not have a prior relationship.

Among primary care providers, Freyer said, studies find a lack of relevant knowledge and experience or comfort level with the AYA cancer patient population and sometimes even an unwillingness to take care of these individuals. “There is some reluctance on the part of these primary care providers in particular to take on the care of these medically complicated patients who they do not know and in the context of a very busy primary care practice that may have difficulty accommodating them.”

Oncologists have their own set of barriers to providing the appropriate transition to survivorship care. Brenda Nevidjon, clinical professor and specialty director of nursing and health care leadership at the Duke University School of Nursing, said that medical oncologists often do not refer their patients to survivorship clinics because they have developed a bond with these patients and want to have the positive experience of seeing them do well. Freyer agreed and added that this behavior does not serve the best interests of the survivors if it interferes with them getting appropriate survivorship care. One study found that pediatric oncologists had low levels

of knowledge of appropriate risk-based screening and survivorship care for a hypothetical female HL patient who had received radiation therapy and anthracyclines. Freyer suggested that as the new generation of oncologists in training become more familiar with survivorship programs, they will be more likely to refer their patients to them.

On the health care system level, there are a variety of impediments to effective care transitions. Cancer patients often lose health insurance coverage, for example, which is a major impediment to follow-up care. There are few seamless referral networks linking treatment centers with survivorship care providers that could aid in care transitions, and medical training generally has little coverage of survivorship care. Another barrier to making the health care transition is a lack of trust on the part of providers. “Pediatric providers need to trust that our adult colleagues will be able to care for these patients appropriately,” Freyer said, “but there is also a need for converse acceptance of responsibility.”

Freyer said that there are currently three basic models for the health care transition: continued care at the original cancer center, care transferred to a primary care community physician, and hybrid care in which care is transferred to community care but with support from the cancer center. For the model in which care is transferred to the community, Rechis said, there is an excellent resource to support primary care physicians providing followup care to AYA cancer patients. The educational program Focus Under 409 has a survivorship module that was created by a partnership between ASCO University and the LIVESTRONG Foundation.

Hudson noted that St. Jude’s Children’s Cancer Center uses another type of hybrid survivorship program in which the original treating physician often consults with physicians in their survivorship care program. Freyer noted that the same type of shared care occurs at CHLA. “The model we use in our institution does not require complete referral and loss of the patient to the cancer survivor program,” he said, adding that many patients are transferred to the survivor program within 2 years of ending therapy rather than the traditional period of 5 years from diagnosis. Consequently, many of these patients in the survivorship program are still on disease-directed follow-up and need scans for disease monitoring, which is not done in the survivorship program. “And if there is an oncologist who really feels it is essential to keep seeing the patient once a year, they are perfectly free to

________________

9 See http://university.asco.org/focus-under-forty (accessed October 8, 2013).

do so and we encourage it if that is what the patient and physician both want,” he said.

Freyer suggested that additional models are needed for transitioning adolescents into adult survivorship care, and he proposed providing tiered care to AYA cancer survivors based on their long-term risks, with the type and intensity of required follow-up differing by group because some patients are at higher risk than others. In the United Kingdom, for example, cancer survivors are subdivided into three different risk groups based on their treatment exposures. These groups are followed by a specialized center, by a primary care physician, or by mail (Eiser et al., 2006). At CHLA, patients are divided into two risk groups based on their treatment exposures and transition to appropriate care at age 21 (see Figure 4). Those with the lowest risk are assessed each year in person by their primary care physicians and virtually by CHLA’s LIFE Cancer Survivorship and Transition Program. Those in the high-risk group are assessed annually at the LIFE Clinic for Adult Survivors. This pilot program will also accept patients from the University of Southern California Comprehensive Cancer Center’s AYA and

FIGURE 4 LIFE Cancer Survivorship and Transition Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

NOTE: LIFE = Long-Term Information, Follow-Up and Evaluation; PCP = primary care physician.

SOURCE: Freyer presentation.

adult survivor programs. “This will offer a lot of opportunity for clinical efficiency and resource sharing as well as research,” Freyer said.

Unlike caregivers for older patients with cancer, most caregivers for AYA cancer patients are parents. The LIVESTRONG online survey found that 82 percent of respondents reported that their parents were their primary caregivers; by contrast, 36 percent of those between 40 and 59 and 3 percent of those older than 60 report their parents as their primary caretakers. About half of the AYAs surveyed reported that their caregivers had to make changes to accommodate their care for a period of at least 2 months; the changes included taking time off of work, switching between full-time and part-time work, and retiring early. “These family members are making changes in their careers and may be the ones that are lending money to pay for the care, so they are definitely being impacted by this cancer diagnosis as well,” Rechis said. “We need to be cognizant of these family members that are supporting AYA cancer patients.”

Communications with AYA Patients

Jacqueline Casillas, director of the University of California, Los Angelese (UCLA) Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Program, Medical Director the UCLA Daltrey/Towshend Teen and Young Adult Oncology Program, and associate professor of pediatric hematology and oncology, spoke about the various factors that health care professionals need to be cognizant of when communicating with AYA patients. For example, health care professionals need to be cognizant that their communication style is AYA age appropriate and emphasizes patient empowerment. Use of diverse channels of communication, such as videos or text messaging, is also important for consideration in this age group. The inclusion of parents and other family members or care givers in the communication channels may be important cultural considerations for diverse groups of AYA cancer patients. Casillas stressed that because a cancer diagnosis often disrupts independence and leads to a young adult living with his or her parents while receiving their cancer care, the traditional patient-doctor dyad may not always be the best way to think about communications. Rather, a patient-doctor-parent triad may be necessary. “The parent may need to be involved in those discussions

about what should be done to promote the health of the AYA patient,” she said.

The degree of involvement of family members in patient communications may differ among ethnicities, Casillas added. For example, her study found that Latino AYAs are more likely to report the need to talk about their cancer care with their families. “Even people who were 35 said they still go back to their family members to help guide them on the type of care that they need,” she said. A major conclusion from her study was that it is critical to include the Latino nuclear family in survivorship care discussions. The study also found that it is critical to include information about health insurance options in a discussion about survivorship care. “The community felt that if we’re not telling them how they can get access to survivorship care, then we shouldn’t be trying to educate them about it,” Casillas said.

Justin Baker, chief of the Division of Quality of Life and Palliative Care at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, said that AYA compliance with medications and procedures can become a battleground as the young patients assert their independence. The proper response, he suggested, is not rigid discipline but rather flexibility with firmness, which builds trust and confidence. In other words, he said, the health care provider should think in terms of partnering, not paternalism.

Casillas described an in-depth qualitative focus group study conducted by Bradley Zebrack in young adults with cancer. This study indicated that patients found it helpful when the provider answered questions, but they considered it hurtful if the provider delivered information in a patronizing manner. This study also found that many AYAs want positive attention and support for feeling more like a normal person again. Consequently, when they are told in a survivorship clinic that they need to maintain a healthy body weight and exercise regularly, they may ask why they are being singled out for healthy behavior that everyone should follow. To respond appropriately, Casillas suggested that care providers put things in context by saying something like, “Yes, we all need to do a good job at this, but there may have been specific treatment exposures that may put you at greater risk, so having a strong healthy heart through regular exercise and healthy eating can be even more important.”

Both written and oral communications are important in fostering appropriate survivorship care, Casillas said. One study that she conducted found that having a written survivorship care plan was associated with AYA cancer survivors being more likely to report that they could actively manage their survivorship care. “Having such a care plan somehow prepares

survivors to be more self-assured about being their own health advocates,” she said. Given how mobile AYAs tend to be and how they tend to get treatment in different health care settings, a written care plan that they can pass on to new providers is especially helpful, Casillas said. “Survivors often say that it is exhausting to have to tell their story over and over again,” she said. Her study also found that ethnic minorities were more likely to report a lack of confidence in managing their survivorship care, and she stressed the importance of addressing language barriers and low levels of literacy among cancer survivors and their families.

Online outreach can also be a valuable way of providing peer social support to AYAs with cancer. “Social media has great potential for enhancing psychosocial support for AYAs,” Zebrack said. Farrish added, “As far as how to reach out to the AYA population, social networking is really a giant—Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc.” For example, she recently posted on Facebook that she got good results on her annual check-up and celebrated 8 years of being cancer-free. “That opened up a lot of doors for a lot of friends,” she said, as friends and friends of friends responded to her post, including those who were recently diagnosed with cancer themselves, and asked if they could speak with her. “It is amazing how far-reaching Facebook and Twitter are,” she added. “I became friends with people I did not really know that well just because they have cancer and I have cancer. It is very beneficial.” She and another AYA cancer survivor also noted that meeting people with cancer through social media sites paved the way for them to form or participate in an in-person cancer support group. Another participant noted that that the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute has a website for young adult patients that fosters peer support and that could be emulated by other centers across the country.

UNMET NEEDS OF AYAs WITH CANCER

Several workshop participants stressed that in addition to their unique medical care needs, AYAs with cancer have a number of informational and psychosocial needs that programs aimed at pediatric cancer patients or older adults with cancer often do not address. These needs include information about their disease, support groups for their age group, preventive health care and fertility preservation, and health insurance. AYAs with cancer also often need financial, practical, and peer support as well as counseling and coping strategies.

Harlan reported that more than one-third of the participants in the

AYA HOPE Study reported an unmet need for service; 16 percent said they needed help with financial planning related to health care; 15 percent needed mental health counseling to address a need that was not met; and 14 percent said they had unmet needs for a support group. More than half of these patients reported six or more unmet information needs, the most common being the need for information about how to handle their concern about getting another cancer. Similarly, in a study using the national MEPS survey data, survivors of AYA cancer were more likely to be unable to get or delayed getting necessary medical care than similar individuals without a cancer history (17.0 percent vs. 12.7 percent).

The CCSS and others have documented “a serious lack of important knowledge that is health related and includes what the previous diagnosis was as well as elements of cancer treatment they have received, what their current state of health and health risks are, and what disease prevention and wellness practices they should follow,” Freyer said. “Many of these survivors really crave knowledge about what their health risks are, what is likely to happen to them, and what they can do to help themselves. If they are not accessing that information by follow-up, they are missing out.”

Zebrack’s unpublished study of AYAs with cancer found that at 12 months after diagnosis, 57 percent indicated that they wanted or needed information not just about their cancer but also about long-term followup, including information about diet and nutrition and fertility. Forty-one percent reported an unmet need for counseling, and 39 percent reported unmet practical support needs such as assistance with health insurance, transportation, and child care. Zebrack noted that a 2010 National Health Interview Survey of 1,177 survivors of adult-onset cancer found that 90 percent reported the reason they were not getting their psychosocial care needs met was because they did not know what services were available to provide them (Forsythe et al., 2013).

“It’s important to pay attention to these psychosocial needs,” Zebrack said, “because they may influence outcomes by affecting adherence to treatment, completion of therapy, and quality of care received.”

Zebrack also stressed the importance of providing peer support to AYAs with cancer. Although people of all ages with cancer need peer support, such peer support is especially critical for AYAs, he said, because of their developmental stage. AYA cancer survivor Chris Prestano concurred, saying, “It’s different for young adults. In my first support group for people with head and neck cancer, I was the same age as these people’s grandkids and great grandkids and half the age of the facilitator.” She finally found a young

adult support group on her own via an Internet networking site called Stupid Cancer.10 “Stupid Cancer focuses more on socializing,” she said. “They do not meet in hospital settings but in restaurants or movie theaters, and sometimes cancer is talked about, but sometimes not.”

Farrish said that the nurses caring for her who were her age provided the peer support she needed. “They turned out to be a bigger support group than the support group I had to attend,” she said. “It is extremely important at our age of diagnosis to have somebody to turn to, to talk about things that are difficult to talk about with your 60-year-old oncologist.”

Rubinstein added, “I seek support in unique ways. I just do not call it support. Social gatherings are the way to do it, or adventure trips, like those offered by First Descents,11 an organization that sends young survivors on free trips. If I had been offered the opportunity to hang out with other cancer survivors at a Redskins game or the movies, I think I would have done it.”

AYAs with cancer also need information on health insurance and other financial support mechanisms. The CCSS found that many insured survivors had difficulty both obtaining health insurance and using it. Most had a lack of knowledge about what their insurance would cover and expressed a willingness to attend an educational program to learn about their health insurance coverage and rights, reported Elyse Park, associate professor of psychiatry at the Harvard Medical School Mongan Institute for Health Policy.