Important Points Made by Speakers

• Straightforward measures such as eliminating sugary drinks from schools, promoting the drinking of tap water, and providing calorie information to consumers can improve the food and beverage environments for members of vulnerable populations. (Story)

• A combination of media campaigns, menu labeling laws, school nutrition policies, and incentives for food and beverage outlets in Philadelphia has contributed to a recent decline in obesity among the city’s children. (Schwarz)

• The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 was a significant step forward in improving the quality of the foods and beverages offered in schools and child care settings. (Fox)

• Other local, state, and federal initiatives, many of which originate with local advocacy, can help reduce obesity rates and population disparities. (Fox)

The second goal of Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention (IOM, 2012a) focuses on the food and beverage environments that people encounter every day (see Box 3-1). As the report notes, major changes have occurred in recent decades in the nation’s food system and in food and eating environments, driven by technological advances; U.S. food and agriculture policies; population growth; and economic, social, and lifestyle changes. These environmental changes have influenced

BOX 3-1

Goal 2 from Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention

Goal: Create food and beverage environments that ensure that healthy food and beverage options are the routine, easy choice.

Recommendation: Governments and decision makers in the business community/private sector should make a concerted effort to reduce unhealthy food and beverage options and substantially increase healthier food and beverage options at affordable, competitive prices.

what, where, and how much Americans eat, and they have had disproportionate impacts on vulnerable populations.

Three speakers addressed food and beverage environments in the context of health disparities. Mary Story, professor in the Division of Epidemiology and Community Health in the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, described ways of pursuing the strategies offered in Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention (IOM, 2012a) for reducing such disparities. Donald Schwarz, deputy mayor for health and opportunity and health commissioner for the City of Philadelphia, described steps taken in the city that serve as a case study for approaches to halting and reversing the rise in obesity among minority populations. Finally, Tracy Fox, president of Food, Nutrition and Policy Consultants, detailed some of the policies affecting the food and beverage environments in schools, restaurants, and neighborhood stores.

STRATEGIES FOR CHANGING FOOD AND BEVERAGE ENVIRONMENTS

Summary of Remarks by Mary Story

The availability of healthy foods is limited in some areas, especially in low-income and minority communities (Larson et al., 2009). These communities tend to have small grocery stores and convenience stores with higher prices than those of large suburban supermarkets (Larson et al., 2009). Unhealthy foods also are marketed more prominently in these communities (IOM, 2012a). And Hispanic and black students are more likely than white students to attend schools surrounded by convenience stores and fast food restaurants (Larson et al., 2009).

The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity states that “individual behavior change can only occur in a supportive environment with accessible and affordable healthy food choices and opportunities for regular physical activity” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001, p. 16). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research makes a similar point: “It is unreasonable to expect that people will change their behavior easily when so many forces in the social, cultural, and physical environment conspire against such change” (IOM, 2000, p. 4).

Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention (IOM, 2012a) outlines five strategies for changing food and beverage environments. The first for governments and decision makers in the business and private-sector community to make a concerted effort to adopt comprehensive strategies for reducing overconsumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. This strategy runs counter to some powerful trends, Story noted. On any given day, 70 percent of males and 60 percent of females between the ages of 2 and 19 consume sugar-sweetened beverages,1 with higher rates of intake among black and Mexican American adults and low-income youth and adults (Ogden et al., 2011). Although the amount of calories consumed in sugary drinks among children and adolescents has declined somewhat over the past decade for almost all age and racial and ethnic groups (the exception being black children aged 2-5), marked disparities persist (Kit et al., 2013). For example, the most recently available data show that black preschoolers consume 114 calories per day from sugary drinks, compared with 61 calories for their white and 72 calories for their Mexican American counterparts (Kit et al., 2013). As an example of how to implement this strategy, Story mentioned efforts to promote the drinking of tap water. Measures such as clean drinking fountains, convenient hydration stations, and signage near beverage outlets identifying sources of tap water could help reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (Patel and Hampton, 2011).

One way suggested by Story to help achieve equity in health opportunities would be to eliminate access to sugary drinks in schools and other settings where children spend their time. According to recent

___________________

1Sugar-sweetened beverages are defined to include all beverages containing added caloric sweeteners, including, but not limited to, sugar or other calorically sweetened regular sodas, less than 100 percent fruit drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, and ready-to-drink teas and coffees (IOM, 2012a).

data, only 12 percent of elementary schools offered access to sugary drinks, compared with 63 percent of middle schools and 88 percent of high schools (Turner et al., 2012). Extending bans from elementary schools to middle and high schools would reduce consumption of these beverages, Story observed. Also, as was pointed out in the discussion session, labels indicating the amount of sugar added to foods, in addition to the sugar already in such foods as milk and yogurt, would help parents, students, and other consumers make informed choices.

The second strategy in Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention for changing food and beverage environments is to increase the availability of lower-calorie and healthier food and beverage options for children in restaurants. Story explained that this strategy is important since low-income and minority neighborhoods are surrounded by fast food restaurants.

The third strategy for changing food and beverage environments is to apply strong nutritional standards for all foods and beverages sold or provided through the government. In addition, business community and private-sector entities operating venues frequented by the public2 should ensure that these healthy options are available at all times. Simply making standards known can have a dramatic effect on consumption, Story noted. For example, providing calorie information about sugary beverages in four corner stores in low-income black neighborhoods in Baltimore reduced purchases of these beverages among youth. Especially effective was a sign saying, “Did you know that working off a bottle of soda or juice takes about 50 minutes of running?” (Bleich et al., 2012).

The fourth strategy is to introduce and utilize health-promoting food and beverage retailing and distribution policies. In this area, Story mentioned incentives, such as taxing strategies, to purchase healthier foods.

The final strategy is to broaden the examination and development of U.S. agriculture policy and research to include implications for the American diet. As Story noted, this strategy involves large-scale food systems and agricultural policies that currently are not aligned with obesity prevention efforts.

___________________

2“Places frequented by the public” include, but are not limited to, privately owned and/or operated locations frequented by the public such as movie theaters, shopping centers, sporting and entertainment venues, bowling alleys, and other recreational/entertainment facilities.

“[When] the City of Minneapolis created what they called Tap Minneapolis … they had blind taste tests, and most people couldn’t tell the difference between tap water and bottled water. In fact, many people preferred the tap water.” —Mary Story

CASE STUDY: OBESITY PREVENTION INITIATIVES IN PHILADELPHIA

Summary of Remarks by Donald Schwarz

Philadelphia is the poorest of the 10 largest cities in the United States, and among those cities for which data are available, it has the highest rate of obesity among adolescents (CDC, 2012; Census Bureau, 2011, 2012). Among counties with more than 1 million residents and the highest population density, Philadelphia county also has the third highest rate of adult obesity, exceeded only by the counties of Bexar, Texas, and Wayne, Michigan (CDC, 2013b; Census Bureau, 2013a).

Responding to these high obesity rates and building on previous initiatives, the city of Philadelphia initiated the Get Healthy Philly program in 2010. Among respondents to a survey of approximately 500 caregivers in the city, the majority did not consider their children overweight or obese, but many were concerned about diabetes (Jordan et al., 2010, 2012b). Approximately 70 percent of respondents understood the health risks of sugar-sweetened beverages and perceived these beverages as an important contributor to obesity (Jordan et al., 2010).

A media campaign used this information to formulate messages that rang true and were salient for minority populations (Jordan et al., 2012b). These messages were seen or heard 40 million times over 15 months, Schwarz stated, and 78 percent of caregivers, who were exposed to a message once every 2 days on average, recalled them. Exposure to a particular television ad called “The Talk” was associated with the belief that consumption of sugary drinks is linked to weight gain and diabetes (Jordan et al., 2012a). Exposure to a radio advertisement called “Jump Rope” targeting African Americans was associated with greater recognition of the sugar content of sugary drinks and increased intentions to replace such drinks with healthier options (Jordan et al., 2012a). In 2012 the Philadelphia City Council reinforced the campaign by passing a

law limiting advertising to 20 percent of window and door space and smaller portions of wall space, Schwarz stated. The consumption of one or more sugary drinks per day in the city has fallen by 20 percent among teens since 2007 and by approximately 5 percent among adults since 2010.3

In 2008, Philadelphia passed the nation’s most comprehensive menu labeling law, which requires that menus provide not just calorie content but also information on sodium, fat, and carbohydrates. Although the law was preempted by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law 111-148, 111th Cong., March 23, 2010), it was implemented in January 2010. Even though Philadelphia cannot enforce the law because of its preemption, compliance among restaurants has been high. Philadelphia also has implemented comprehensive school nutrition policies since 2004 (Robbins et al., 2012). The city’s schools no longer offer sugary beverages in vending machines, they are subject to snack and á la carte standards, and nutrition education is now provided in classrooms through funds from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Schools also have removed fryers from their kitchens and have switched to 1 percent milk. The city created wellness councils in 171 schools in 2010 and has assessed school food procurement and contracting processes (Get Healthy Philly, 2011). In 2012 it become the first school district in Pennsylvania to implement new federal school nutrition standards.

Of the more than 2,400 corner stories in Philadelphia, more than 600 are offering and promoting healthier products in exchange for modest incentives, marketing materials, and training (Get Healthy Philly, 2011). Schwarz stated that more than 150 stores have received shelving or refrigeration units with which to display and store perishables. The city’s new zoning code also encourages the incorporation of fresh food sales into commercial and mixed-use developments by offering density bonuses that do not count the square footage of produce display areas against the maximum area for commercial activity. In corner stores, while the availability of healthy foods has improved, purchases have not yet changed. Improving awareness of healthier choices through school

___________________

3Based on data for teens in grades 9 through 12 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (2007-2011) and data on adults from the Public Health Management Corporation’s Community Healthy Data Base 2012 Southeastern Pennsylvania Household Health Survey (2010-2012).

and community nutrition education could alter this lack of response, said Schwarz.

Schwartz mentioned additional changes in the city, including

• Ten new farmers’ markets have opened in low-income communities in partnership with The Food Trust (Get Healthy Philly, 2011).

• Participating farmers’ markets offer an incentive to SNAP recipients by providing $2 of free fruits and vegetables for every $5 of SNAP benefits spent at the market. Between 2010 and 2012, this program contributed to a 335 percent increase in SNAP redemption at farmers’ markets citywide (Get Healthy Philly, 2011).

• A universal feeding pilot program in 200 public schools has been carried out in Philadelphia since 1990, which eliminates the need for distributing and collecting income eligibility paperwork. Under this program, eligibility for the school breakfast and lunch programs is based on the proportion of low-income children in schools. Participation in both programs has increased as a result, Schwartz said.

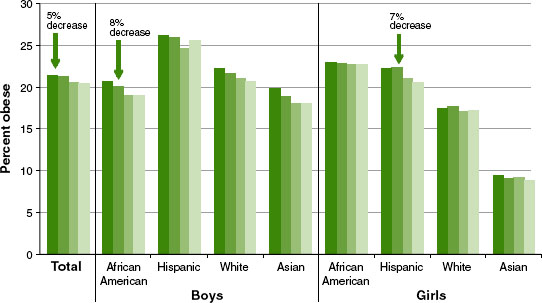

The above changes have been associated with a decline in obesity among schoolchildren in Philadelphia from 2006-2007 to 2009-2010 (see Figure 3-1), Schwarz reported. He added that the city has also seen a slight reduction in adult obesity as measured by the prepregnancy weight of women on birth certificates.

From his experiences, Schwarz drew several conclusions:

• Cross-sectoral collaboration is key both within and outside of government.

• Effective programs should be scaled up when funding allows.

• Citywide and organizational policies must undergird programmatic efforts.

• Policies and programs take time to have a cumulative effect.

• Evaluation is critical. Not all interventions will succeed as initially designed.

To these conclusions, Schwarz added, during the discussion session, that people need to be given a voice and that ways of accomplishing this differ across jurisdictions. As members of minorities become population

majorities in many jurisdictions, their preferences eventually will be heard and make themselves felt.

Schwarz also listed several questions that need increased attention:

• How can school food programs be supplemented when public school budgets are being slashed?

• How can the marketing of unhealthy products be reduced or eliminated?

• How can physical activity be promoted, especially for girls?

• How can federal public health funding for prevention and nutrition assistance be sustained in a period of deficit reduction?

During the discussion period, standing committee member Thomas Robinson, Irving Schulman, M.D., Endowed Professor in Child Health at Stanford University, noted that the advocacy and public health communities are ahead of researchers in knowing what programs are effective in changing public attitudes and behaviors. Schwarz responded that much still remains to be learned about interventions at the environmental level, where both politics and the diversity of population groups are prominent factors.

FIGURE 3-1 Obesity rates among Philadelphia schoolchildren (aged 5-18), 2006-2007, 2007-2008, 2008-2009, and 2009-2010.

SOURCE: Robbins et al., 2012.

“Small programs that have been piloted are incredibly important tests, but government has to be courageous and have the resources to scale them for the whole population. It’s the only way to ultimately reach disadvantaged populations.” —Donald Schwarz

Summary of Remarks by Tracy Fox

Vulnerable populations have fewer opportunities than others to make healthy choices (RWJF, 2012). The foods to which they have ready access often are of poor nutritional quality (RWJF, 2012). Fast food marketing targets these populations (Kunkel et al., 2013), and their neighborhoods tend to have more fast food restaurants and convenience stores (RWJF, 2012).

Students in schools in these neighborhoods also are disadvantaged. They are less likely to attend a school with a wellness policy or nutrition education and to have access to healthy foods and beverages (Bridging the Gap, 2013). They are less likely as well to participate in school sports programs or attend a school that shares its recreational facilities outside of school hours (Bridging the Gap, 2013).

Given this background, Fox explained that the passage of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (Public Law 111-296, 111th Cong., December 13, 2010) was a significant step forward in improving the quality of the foods and beverages offered in schools and child care settings. The act improves the nutritional quality of the meals served in these settings, increases access to school meals, establishes nutrition standards for all foods sold in schools, strengthens local wellness policies, expands the after-school meal program, and reduces the administrative burden in child nutrition programs. School meals now have less unhealthy fat, less salt, fewer calories, more low- and nonfat dairy, more fruits and vegetables, and more whole grains. Fox explained that under proposed standards for the Smart Snacks in School program, which were about to be finalized at the time of the workshop, students would consume more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and lean proteins; less fat, sodium, and sugar; fewer sugar-sweetened beverages; and more water.

Other federal nutrition programs also have gained a new emphasis on obesity prevention, Fox pointed out. The food packages under the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) were revised in all states by 2009, and retail outlets that accept WIC vouchers are now providing healthier products. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is working to update the meal patterns in the Child and Adult Care Food Program. And at the time of the workshop, the Food and Drug Administration was working on a final ruling on menu labeling and updating the nutrition facts panel on packaged goods.

Also at the time of the workshop, Congress was debating the Farm Bill, which has a major impact on the nutrition of vulnerable populations, Fox noted. Historically, about three-quarters of the funding under the Farm Bill has gone to SNAP, in which approximately 46 million people have participated since June 2012 (CBO, 2012).4 More than 90 percent of SNAP participants are children, the elderly, or those with disabilities, and the program has one of the lowest fraud rates of all federal programs, yet it often is subject to political attack, Fox observed. The Farm Bill also features several incentive-based approaches that would help SNAP participants use their benefits in nutritionally sound ways, said Fox, including support for farmers’ markets and financing for healthy food.

Fox noted that states and localities, as well as the federal government, have instituted innovative programs designed to reduce obesity rates. For example, many cities are promoting the development of healthier public places. The idea is that when people are playing outside or returning from a hike, they should not be confronted with an array of unhealthy snacks and beverages. The City of San Antonio has limited sugary beverages in county government offices (Bauch, 2010). The New York City Department of Health has been emphasizing procurement policies that promote health, as has the federal government—for example, the Department of Defense through its Healthy Base Initiative.5

Many of these programs, even at the federal level, started with local advocacy. Good ideas percolate up from the local level and then can spread nationally through federal legislation, Fox noted. These programs have been influential in reducing disparities. If funding levels for such

___________________

4See http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/29snapcurrpp.htm for details by state.

5Details are available at http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=15867.

programs are reduced, the vulnerable populations they serve will be negatively affected, said Fox.

“The reason why we need these programs protected is because the target populations are those … that really need these programs. Threats to funding levels will significantly impact these populations.” —Tracy Fox