APPENDIX E-9

American Physical Society Written Testimony

Committee on Minorities in Physics & Committee on the Status of Women in Physics

Trends

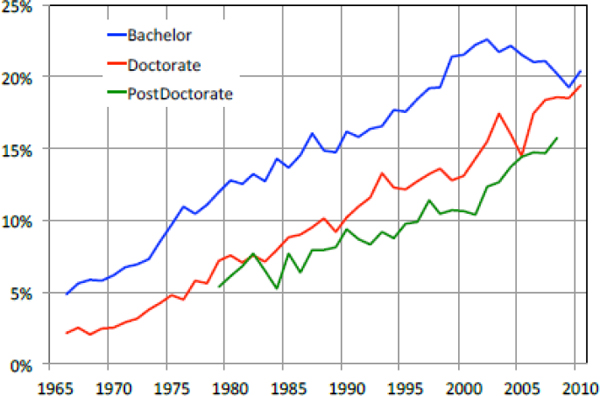

The field of physics has struggled to increase representation of women and minorities into undergraduate and graduate physics programs. Although about 50 percent of the students who take physics in high school are female, the ratio of females to males in the awarding of undergraduate bachelor degrees is only about 20 percent. Further, the percentage of women that take AP physics roughly reflects the ratios seen in undergraduate degrees. Roughly the same percentage of females receives PhD’s in physics. According to Rachel Ivie21 of the American Institute of Physics (AIP), “physics continues to have the lowest representation of women.”

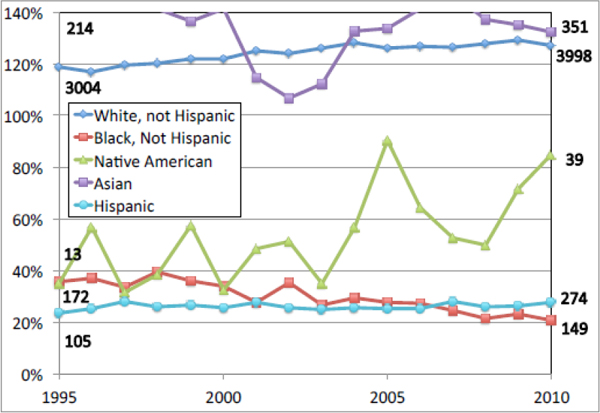

The situation for Hispanics and African Americans is somewhat worse. The fraction of physics undergraduate degrees, when normalized for changes in the US population, shows that these two groups remain woefully underrepresented. Hispanics have increased their numbers significantly in the US population (more than a factor of 2.5x increase in the past 15 years). However, the gains show only a small increase in representation in physics. African Americans, on the other hand, have decreased both in actual numbers and as a fraction of degrees granted. White and Asian students continue to be overrepresented.

Additionally, while 40-50 percent of white and Asian students take at least one physics course in high school, only about 25 percent of the students of color have taken one physics course in high school. Despite the low numbers, there has been a steady increase among all groups in the percentage of students taking physics in high school.

__________________

21 Rachel Ivie and Casey Langer Tesfaye, Women in physics: A tale of limits, Physics Today 65, February 2012.

Figure E-9-1 Percentage of women receiving degrees and postdoctoral positions in the U.S.

Source: National Science Foundation and Department of Education.

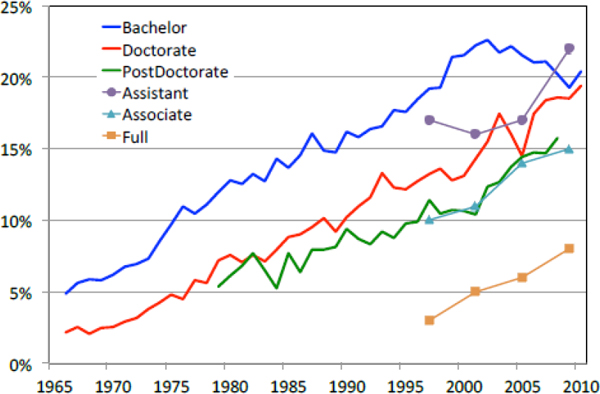

With employment data from the AIP overlaid onto Figure E-9-1, Figure E-9-3 indicates that assistant professors in physics are hired at rates at or above the production rate of PhDs. This is especially apparent when one considers that the data for professors should be moved to the left on the graph to indicate the population of PhDs that feed this crop of professors.

Figure E-9-2 Undergraduate degrees in physics adjusted for the changing demographics of the U.S. 100 percent indicates representation in line with US population fractions.

Source: Department of Education, IPEDS; US Census.

Figure E-9-3 Data on the fraction of professors at each level is overlaid on data from Figure E-9-1. Since these are total numbers in each category, the represent a hiring average over a number of years. To match the group with the supply, each one should be “slid” left the number of years representing the mean number of years since their PhD.

Source: AIP.

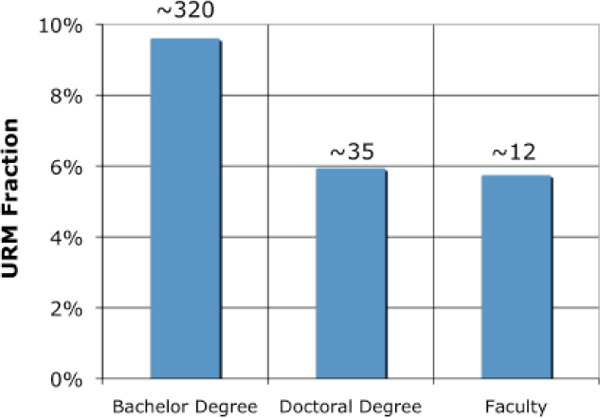

Although women are hired at a rate consistent with their graduation rate, it is also clear that they remain underrepresented in physics. Minority women suffer from the combined factors of underrepresentation as women and as minorities. Figure E-9-4 shows that only about 5-6 percent of all PhDs granted to US citizens are given to underrepresented minorities (African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans). The numbers of these individuals are exceedingly low, amounting to only about 30-35 PhDs per year. When this is coupled with the roughly 20 percent of PhDs given to women, we are counting only 6 or 7 PhDs given to women of color each year in physics in the entire US. The good news is that it appears that minorities are hired as Assistant professors at the same rate as they receive PhDs, and given the similar data for women, one can probably assume that women of color are hired at roughly the same rate as their majority colleagues.

Figure E-9-4 Percentage of degrees and appointments at the assistant professor rank for underrepresented minorities. Numbers on each bar represent roughly the number each year.

Challenges

When considering these data, there are two clear issues to consider when discussing possible actions to improve the situation faced by underrepresented women in physics:

1) Isolation

2) Representation

There are a number of studies that indicate isolation as a factor that significantly impacts women of color as well as minorities and women more generally. If only 6 PhDs are granted each year to women of color, and only a third of these seek academic positions (based on the averages for the field), then these two women are unlikely to see themselves as much of a cohort or peer group. Some APS programs begin to address this issue, and we also have recommendations of possible avenues to pursue to lessen the impact of this concern.

Second, minority women PhDs are produced in very small numbers, so an obvious set of solutions seeks to address how to increase these numbers. Again, there are numerous studies and papers addressing potential remedies. These typically address “STEM” (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) as a single discipline, but clearly this is not the case as representation of these various groups varies considerably between disciplines. In biological sciences, the rate of graduation of PhDs is roughly equivalent between men and women, and in fact bachelor’s degrees in this field are overrepresented in women. Any reasonable set of solutions needs to take this into account.

As US colleges are already majority female (57 percent) and are increasingly enrolling more minority students (44 percent), women — especially those living in the intersection of race and gender — represent a growing source of untapped domestic talent to help meet the nation’s STEM needs. Moreover, although policies aimed at increasing women of color should be based on empirical research on women of color pursuing STEM educations, there is a documented paucity of such work.

Programs of the American Physical Society

The American Physical Society (APS) is the largest organization of physics in the country and has long been a supporter of increasing diversity in the field of physics. There are two committees in the APS who focus on this particular mission. The Committee on Minorities (COM) and the Committee on the Status of Women in Physics (CSWP). COM works to increase the number of historically underrepresented minorities, notably African Americans, Hispanic, and Native Americans, who earn degrees in physics and pursue successful careers in physics in the United States. COM conducts site visits and offers a minority scholarship for undergraduate physics majors. The APS is also beginning a major effort to build sustainable bridge programs throughout the country that will help improve the pipeline of minority undergraduates into graduate school and beyond. Other programs include the annual Edward A. Bouchet Award, travel grants, and a roster that provides names and qualifications of several hundred women and minorities in physics. (aps.org/programs/minorities/).

The CSWP is committed to encouraging the recruitment, retention, and career development of women physicists at all levels. This is accomplished through a number of initiatives such as the Climate for Women in Physics Site Visit program, organized by the CSWP, which helps physics departments and research facilities assess and improve the climate for women in physics at their institutions. (aps.org/programs/women/) The Blewett Fellowship for Women Physicists enables women to return to physics research careers after a career interruption. The CSWP promotes recognition of women physicists through its Woman Physicist of the Month program (aps.org/programs/women/scholarships/womanmonth/) and publishes The Gazette, the official newsletter of the CSWP, in conjunction with the Committee on Minorities. The APS COM and CSWP have each taken on important roles in the issues that face minorities and the issues that face women in the field of physics.

Policy Recommendations

To address the two issues related above, we recommend the following actions:

1) Isolation

a. Provide networks that allow women to link up and form support networks. These should be discipline specific to allow access to information that is critical to success within the discipline.

b. Develop and support projects that look toward understanding identity in science. There are a number of studies that identify conflicts between identities as women or minorities and identity as science learners. Methods to develop physics identity need to be further studied and implemented.22

2) Representation

a. Improve the transition between undergraduate and graduate studies. The data in Figure E-9-4 indicates that the fraction of underrepresented minorities who receive bachelor’s degrees is nearly twice the fraction who subsequently complete a PhD. We recommend that support be found to plug this significant hole in the

__________________

22 Zahra Hazari, Gerhard Sonnert, Philip M. Sadler, Marie-Claire Shanahan, Connecting High School Physics Experiences, Outcome Expectations, Physics Identity, and Physics Career Choice: A Gender Study, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, December 2009; Angela Johnson, Jaweer Brown, Heidi Carlone, and Azita K. Cuevas, Authoring Identity Amidst the Treacherous Terrain of Science: A Multiracial Feminist Examination of the Journeys of Three Women of Color in Science, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, December 2010

education pipeline by supporting bridging efforts between these degrees. Current examples of such programs in physics exist at Vanderbilt University, Columbia, MIT, and the University of Michigan.

b. Improve retention of students in the introductory courses. As indicated in the recent PCAST report, “Engage to Excel,” a significant loss of talent for this country is dismissed from studying physics by their first course in the subject as an undergraduate. Physics is particularly egregious at this boundary, and education research has demonstrated techniques that have documented success at lowering the drop/fail/withdraw rates particularly for women and minorities using enhanced pedagogical techniques. These active engagement methods e.g., SCALE-UP from NC State, have been tested and successfully implemented at a number of schools, but there are insufficient resources to more widely disseminate the professional development needed to successfully adopt these new techniques in a more widespread manner. These could be successfully enhanced through the NSF Transforming Undergraduate Education in Science (TUES) program, or by other methods through national professional societies. Curriculum revision in introductory physics guided by results from Physics Education Research has also played a major role in increasing the quality of these courses and has promoted better prepared students who are more likely to continue on in physics.

c. Directly address stereotype threat. Stereotype threat has been widely documented as a key factor in reducing the success of women and minorities in a number of studies.23 Straightforward interventions are possible, but again professional development is required to help faculty implement such solutions. The critical point is in the first courses of an undergraduate education, but making known the issues and techniques that can ameliorate these factors at all levels is needed. Programs within NSF’s Education and Human Resources Directorate and especially within the Division of Undergraduate Education have the greatest potential to impact faculty in these areas.

d. Make high quality physics instruction available to every high school student. Currently only 37 percent of all high school students take physics, and less than half of the classes are taught by a teacher with significant background in the subject according to the Department of Education’s Schools and Staffing Survey. In addition, studies have shown that poverty is most strongly correlated with the failure of schools to offer courses in physics.24 Consequently, students, including women of color, who are educated in poor school districts, suffer from a lack of adequate preparation for college and technical jobs. Currently high school physics teachers are in drastically short supply with only about a third of the needed positions filled with adequately educated teachers. Support through the NSF, and Department of Education to address this is needed. The NSF Noyce Program, which supports preservice teachers and places them in high-needs school districts can also aid in providing high quality physics instruction. The APS PhysTEC project, which focuses specifically on physics can also aid in this

__________________

23 A. Miyake, L.E. Kost-Smith, N.D. Finkelstein, S.J. Pollock, G.L. Cohen & T.A. Ito, Reducing the Gender Achievement Gap in College Science: A Classroom Study of Values Affirmation, Science 330, 1234 (2010)

24 Kelly, A.M., & Sheppard, K., Secondary physics availability in an urban setting: The relationship to academic achievement and course offerings, American Journal of Physics, 77(10), 902-906, (2009)