3

A Comprehensive Framework

for Ensuring the Health of an

Operational Workforce

When Congress passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 19701 with the intent of ensuring safe and healthful working conditions in the United States, it found that “personal injuries and illnesses arising out of work situations impose a substantial burden upon, and are a hindrance to, interstate commerce in terms of lost production, wage loss, medical expenses, and disability compensation payments” (Sec. 2). In recent years, the impacts of poor health and injuries on productivity, profit, and the readiness of a workforce to accomplish its basic mission have been strong driving forces for new workplace initiatives designed to improve employee health and safety. Beyond that motivation, however, the committee asserts that safe and healthful working conditions are a matter not only of workforce effectiveness but also of basic civil rights and expectations.

As described in previous chapters, a significant proportion of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) workforce operates outside of conventional workspaces on a routine or recurring basis, creating challenges to protecting employee health not encountered in most other federal agencies. A comprehensive approach to workforce health protection at DHS must be responsive to these challenges. This chapter delineates a comprehensive framework for ensuring the health of an operational workforce. It then details in turn the key functions that support the two pillars of this framework—medical readiness and medical support for operations. The final section addresses the integration of essential workforce health

__________________

129 USC 651.

protection functions that underpins the entire framework and is vital if the functions are to be carried out successfully.

WORKFORCE HEALTH PROTECTION AND MISSION SUCCESS

Former DHS Deputy Secretary Lute (2013), addressing the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Department of Homeland Security Workforce Resilience, said that homeland security is not about unity of command but unity of effort. The DHS workforce, although highly diverse, is united by its common mission—to create a safe, secure, resilient homeland where the American way of life can thrive (Lute, 2013). The ability to fulfill that mission depends on the mission readiness of the DHS workforce. A workforce that is mission ready is physically capable, mentally prepared, trained, equipped, and adequately supported for the job. Protecting the homeland can be physically and mentally demanding, with many inherent risks. Consequently, mission readiness depends, in part,2 on

- a workforce that is medically ready (free of health-related conditions that would impede the ability to participate fully in operations and achieve the goals of its mission); and

- the capability to provide medical support to the workforce during planned and contingency operations.

Workforce health protection, as an overarching strategy for promoting, protecting, and restoring the physical and mental well-being of the workforce, addresses both of these requirements. It encompasses a broad set of activities focused on promotion, prevention, surveillance, detection, early intervention, treatment, recovery, and reintegration. The health protection program must be more, however, than the sum of its parts. Like the agency itself, workforce health protection must be about unity of effort if it is to be effective.

A FRAMEWORK FOR ENSURING THE HEALTH OF AN OPERATIONAL WORKFORCE

In its statement of task, the committee was asked to identify the key functions of an integrated occupational health and operational medicine infrastructure. It did so by examining and identifying commonalities in the major elements of employee health protection and promotion programs of public and private organizations. While recognizing the limitations of

__________________

2There are many other determinants of mission readiness that are beyond the scope of this report.

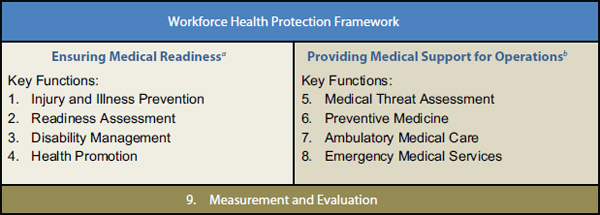

FIGURE 3-1 A two-pillar framework with nine essential functions that support the health of an operational workforce.

aMedical readiness is the extent to which members of the operational workforce are free of health-related conditions that would impede their ability to participate fully in operations and achieve the goals of their mission.

bMedical support for operations consists of preventive and responsive medical and health support services provided outside of conventional workplaces during routine, planned, and contingency operations to employees and others under the organization’s control.

applying Department of Defense (DoD) models to a civilian government agency, the committee found the DoD force health protection concept (DoD, 2004) useful in framing the key functions of workforce health protection for DHS. The committee therefore adapted the DoD force health protection model to derive a framework for ensuring the health of a civilian operational workforce (see Figure 3-1).

The two pillars of this framework reflect the two medical requirements for mission readiness: medical readiness and operational medical support. In total, as shown in Figure 3-1, the committee identified nine essential and interconnected functions of workforce health protection that support an operational workforce. Measurement and evaluation spans both pillars and serves as a foundation for the framework. Without measurement and evaluation, the medical readiness and medical response capability of the DHS workforce cannot be assessed, reported, or improved.

A unified strategy for workforce health protection will integrate and therefore ensure coordination of the nine key functions, resulting in

- a prevention-focused approach to workplace injury and illness that creates a safe, supportive working environment;

- ongoing readiness assessment to ensure an individual’s continued ability to carry out his/her responsibilities fully and safely;

- proactive medical case management to restore employees to a state of health and readiness as rapidly as possible;

- adequate and effective preventive and responsive medical support services available when needed;

- promotion of physical fitness and healthy lifestyle choices to optimize human performance and readiness; and

- ongoing measurement and evaluation for decision making, accountability, situational awareness, and continuous quality improvement.

The underlying infrastructure that serves to integrate these functions includes the doctrine (plans, policies, and standards), organizational constructs (reporting structures, governance mechanisms), and resources (qualified personnel, budgets, information management systems) that enable mission capability.

The subsections below provide a description of the four key functions for ensuring medical readiness that form the first pillar of the workforce health protection framework presented above (see Figure 3-1) and explain their importance. The remainder of the framework is discussed later in the chapter.

Injury and Illness Prevention

In the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, “Congress declares it to be its purpose and policy … to assure so far as possible every working man and woman in the Nation safe and healthful working conditions … by encouraging employers and employees in their efforts to reduce the number of occupational safety and health hazards at their places of employment, and to stimulate employers and employees to institute new and to perfect existing programs for providing safe and healthful working conditions.” To achieve this purpose, it has since 1970 been customary and expected practice for all but the smallest public and private employers to establish and implement comprehensive occupational safety and health programs.

Occupational safety and health programs facilitate risk management—a continuous, multistep process designed to reduce risks to health, mission, and property. The three main elements of risk management are (1) hazard identification, (2) risk assessment, and (3) risk control. Hazards are identified by observation (through workplace inspections and job hazard analyses) or from past experiences (e.g., root cause and trend analyses following injuries and illnesses). Once a hazard has been identified, a risk assessment process is used to determine the likelihood that the hazard

will cause a mishap and the severity (human health and property damage) should a mishap occur. This information is used in the assignment of risk assessment categories, which indicate the level to which risks from a hazard should be managed. Risks can be controlled through (1) engineering controls, (2) administrative procedures/work practices (e.g., training, standard operating procedures, posted signs, vaccination), and (3) the use of personal protective and other safety equipment (USCG, 2013). In operational settings, tension can exist between occupational safety and health objectives and mission requirements. Operational risk management enables risk-based decision making, the goal of which is to control risks to acceptable levels consistent with the organization’s mission—minimizing risk without compromising mission success.

Occupational safety professionals are often focused on the prevention of traumatic injuries and workplace fatalities through mitigation of safety hazards, whereas industrial hygienists provide expertise on the identification and control of health hazards from acute or chronic exposure to chemical, biological, and physical agents. Ergonomists are concerned with ensuring that the design of workspaces, equipment, and work tasks suits the individual worker so as to prevent disorders resulting from cumulative trauma, most notably musculoskeletal disorders (NRC, 2000). Although occupational safety and health program staff have an important role to play in providing guidance and performing evaluations to ensure compliance with policy and regulations, risk management is considered a primary responsibility of those most familiar with their workplace hazards—individuals and operational units at the local level (The Conference Board, 2003). A centralized oversight entity cannot predict safety and health risks for each worksite and so must provide employees with the tools and information to make sound risk management decisions.

Requirements for Federal Agency Occupational Safety and Health Programs

Section 19 of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 requires that all federal employees be provided with “safe and healthful places and conditions of employment.” To this end, the act assigns responsibility for establishing and maintaining “an effective and comprehensive occupational safety and health program” to heads of federal agencies. Further roles and responsibilities for federal agency occupational safety and health programs are delineated in Federal Executive Order 121963—Occupational Safety and Health Programs for Federal Employees (1980)—which requires

__________________

3Executive Order 12196—Occupational Safety and Health Programs for Federal Employees, 45 FR 12769, 3 CFR, 1980 Comp., p. 145. Feb. 26, 1980.

federal agencies to apply occupational safety and health practices that are required of nongovernmental activities regulated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and outlines several basic administrative controls to support this compliance. All of the items delineated in that executive order bear on the subject of the present analysis, but two specific requirements placed on federal agencies merit special mention: “designate an agency official with sufficient authority to represent the interest and support of the agency head to be responsible for the … program,” and “operate an occupational safety and health management information system.” As required by Executive Order 12196, the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 29, part 1960 (29 CFR 1960) specifies the basic program elements that all federal agency occupational safety and health programs should encompass. Provisions built into those elements give agencies the flexibility needed to implement programs tailored to their organizational and mission requirements.

Federal agencies must submit annual reports of occupational injuries and illnesses to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and OSHA. The Bureau of Labor Statistics uses this information to generate aggregated injury and illness data from across the federal government; OSHA uses it to target federal agencies for compliance inspections (29 CFR 1960). OSHA administers citations but does not fine federal agencies for failure to comply with regulations and standards (OSHA, 2013).

Despite the above regulations, tens of thousands of injuries and illnesses, many of which are preventable, continue to occur each year in federal workplaces. The annual government-wide workers’ compensation costs associated with these events total almost $3.0 billion (OWCP, 2013). To address this burden, President Obama established a 4-year Protecting Our Workers and Ensuring Reemployment (POWER) initiative in July 2010 (Obama, 2010). The POWER initiative requires all executive departments and agencies, through aggressive performance targets, root cause analysis, and adoption of proven safety and health management programs, to improve their performance in workplace safety and health in seven areas:

- reducing total injury and illness case rates,

- reducing lost time injury and illness case rates,

- analyzing lost time injury and illness data,

- increasing the timely filing of workers’ compensation claims,

- increasing the timely filing of wage-loss claims,

- reducing lost production day rates, and

- speeding employees’ return to work in cases of serious injury or illness.

Through these objectives, the POWER initiative places shared responsibility for employee health on the occupational safety and health programs designed to prevent injury and illness and on disability management programs responsible for helping injured and ill employees return to work as quickly as possible.

Best Practices in Occupational Safety and Health

Best practices in occupational safety and health can be viewed as features of a systematic approach that leads to highly effective control of injuries, illnesses, and disability and thereby to a healthier workforce. Such a systematic approach—called by some an occupational safety and health management system or, in OSHA’s terms, an injury and illness prevention program—provides a “flexible, commonsense, proven tool to find and fix hazards before injuries, illnesses, or deaths occur” (Hagemann, 2013). OSHA has identified six core elements essential to an injury and illness prevention program: management leadership, employee participation, hazard identification, hazard prevention and control, education and training, and program evaluation and improvement (Hagemann, 2013). The importance of these elements to the effectiveness of occupational safety and health programs is supported by research on the characteristics of an occupational safety and health management system that appear to lead to the greatest improvement in safety and health outcomes (Shannon et al., 1997).

Medical Countermeasures Programs

Medical countermeasures programs, which span the fields of occupational medicine and occupational safety and health, are critical not only to ensuring public health but also to preventing illness among federal employees who serve in operational capacities. The anthrax mailings in 2001, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003, and the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009 highlighted the importance of preparedness planning for large-scale chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear events that can threaten both public health and business operations across the globe. Workplace plans to ensure continuity of business operations are particularly important for those members of the workforce who are considered mission-essential personnel; strategies for distribution and dispensing of medical countermeasures4 to prevent and mitigate the health effects of

__________________

4Medical countermeasures include biologics (e.g., vaccines, antimicrobials, antibody preparations), nonbiologic materials and devices (e.g., ventilators, diagnostic devices, personal protective equipment such as face masks and gloves), and public health interventions (e.g., contact and transmission interventions, social distancing, community shielding).

chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear hazards are critical elements of such contingency plans. Agencies that play a key role in the federal response to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear events, including the Department of Health and Human Services and DHS, are required by executive order (Obama, 2009) to have in place programs that enable the capability to dispense medical countermeasures to their workforce rapidly following such an attack to ensure that mission-essential functions of federal agencies are not disrupted.

Readiness Assessment

Workers in many occupations may, in the course of their daily operations, be required to perform work that is arduous and/or hazardous in nature. Not only must they be capable of performing those duties, but they must be able to so without posing a threat to their own health and wellbeing or that of others. Key to ensuring this capability is readiness assessment, which includes developing medical and physical ability standards and conducting fitness-for-duty and fitness-for-deployment evaluations.

Medical and Physical Ability Standards

There is no one accepted method for the development of medical and physical ability standards; however, two criteria (i.e., fitness-for-duty drivers) generally are considered: (1) essential job tasks, and (2) the environmental conditions and circumstances under which those tasks must be performed. These criteria are identified through a job task analysis, which can be conducted internally or contracted out and ideally involves human resources and medical personnel, as well as individuals currently employed in that occupation. The California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training recommends a variety of techniques for conducting job task analyses, including “review of current job descriptions, interviews with supervisors and employees, development and administration of questionnaires, use of daily job diaries by employees, [and] review of records (e.g., police reports, critical incident reports).” Also recommended is the use of someone experienced in conducting such analyses and consultation with “several employees under a range of conditions” whenever possible (Goldberg et al., 2004, p. 23). Generally, the resulting list of essential job functions is not comprehensive but focuses on those tasks that impact a physician’s determination of an individual’s ability to do the job.

The development of medical and physical ability standards from the results of a job task analysis is not a simple process of identifying disqualifying medical and physical conditions. For most conditions, simply having the condition does not preclude an individual from being able to perform

essential job tasks, as the condition’s impact can depend on its degree or severity. Generally, medical and physical ability standards provide guidance to physicians on how to conduct a thorough examination (by body system) and how to quantify safety risks associated with having a given condition. The standards are subject to much interpretation, and individualized assessments are always required. Additionally, the standards and guidance for fitness for duty need to be maintained as living documents, reviewed and updated periodically, because the evidence base (research and experience) changes over time.

For legal defensibility, medical and physical ability standards need to be closely linked to the essential tasks of a job; consequently, standards developed by one organization cannot necessarily be applied to the jobs of another. For example, the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine’s consensus guidance developed for medical evaluation of patrol officers may not be universally applicable across all law enforcement officer positions given the diversity of their functions. Essential job tasks for special weapons and tactics (SWAT) team members may be very different from those for patrol officers. Similarly, medical standards for 1811 series5 criminal investigators at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) may or may not be applicable to 1811 series investigators at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) if they are performing different tasks or operating under different conditions. At the same time, however, sharing of medical standards for the purpose of adaptation, particularly for those agencies with employees under the same job series, could reduce the burden (financial and labor) of setting standards and lead to increased uniformity. For example, the FBI and the National Park Service have already developed medical standards for federal law enforcement officers that could be adapted by other agencies. Given that the FBI’s process for developing these standards cost approximately $3.5 million (Wade, 2013), this represents a valuable opportunity for interagency collaboration to improve efficiency across the government.

Medical and physical qualification for federal positions The authority for federal agencies to establish medical evaluation and clearance programs is accorded by Title 5, part 339 of the Code of Federal Regulations (5 CFR 339). Such programs are justified under the regulation as a means of protecting the health of employees whose work poses significant health and safety risks to themselves or others due to occupational or environmental exposures or other demands. The regulation does impose some constraints

__________________

5The 1811 series is the Office of Personnel Management job series for criminal investigators in the federal government.

on federal agencies to ensure that fitness for duty is evaluated on a case-by-case basis:

- The agency is required to grant a waiver when the evidence indicates that an applicant or employee who does not meet the medical or physical standards can, with or without reasonable accommodation, perform the essential functions of the job without endangering him/herself or others.

- Applicants cannot be disqualified from a position based on medical history alone; medical history may be disqualifying only if (1) the medical condition is disqualifying, (2) there is a possibility of its recurrence, and (3) recurrence poses a significant risk of harm to themselves or others.

The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) is responsible for establishing or approving medical standards for government-wide occupations (5 CFR 339). However, when a job series is associated predominantly with a single federal agency (i.e., more than half of all those employed under that job series are employed within a single agency), that agency may establish medical standards for the position without OPM approval. An example of the latter is the border patrol agent job series (GL-1896), which is exclusive to CBP. Agencies do not need OPM approval to establish physical standards, but in accordance with 5 CFR 339, the requirements must be supported by the essential duties of the position and clearly articulated in the position description.

Waivers As noted above, 5 CFR 339 requires that agencies grant a waiver when an individual does not meet medical or physical standards but demonstrates evidence of being able to perform the essential functions of the job safely. Employers can grant waivers but impose restrictions on duty as part of a risk management solution that keeps people on the job who have demonstrated their performance capability. For example, someone diagnosed with major depressive disorder may be granted a waiver on condition of demonstrating active treatment and submitting to annual evaluations (McMillan, 2013)—an important accommodation as the incidence of mental health disorders continues to increase. Waiver processes grant employing agencies considerable flexibility and can help address concerns about how to handle medical issues uncovered during periodic evaluations—concerns that may deter employers from instituting regular medical evaluations. A fair waiver process also can help build trust if employees understand that a diagnosis will not necessarily mean the loss of their job. As described above, line personnel who are intimately familiar with the requirements of the job ideally are involved in decisions regarding waivers, in

consultation with knowledgeable medical authorities. A waiver guide, as is used in some DoD agencies, can help ensure consistency in waiver decisions.

Fitness-for-Duty Evaluations

Fitness-for-duty evaluations compare an individual’s medical status and physical abilities against established medical and physical qualifications. Standards and guidance materials ensure that such practices are transparent, fair, and evidence based. For example, the National Fire Protection Association 1582 Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments6 requires that candidates undergo a medical evaluation (to include a medical history, medical examination, and laboratory testing) prior to employment and annually thereafter, the purpose of which is to identify medical conditions that may interfere with the individual’s ability to perform the essential job tasks safely. The standard divides medical conditions into two categories—those that would preclude a team member from safely performing essential job tasks in training or operational environments, and those that could do so, depending on the degree or severity of the condition. The ability of applicants and incumbents with medical conditions in the latter category to perform essential job tasks safely must be assessed before a determination regarding employment can be made.

Similar guidance materials for medical evaluation of law enforcement officers have been issued by the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM, 2010)7 and the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (Goldberg et al., 2004). Commonalities among such standards and guidance include

- ensuring compliance with applicable law and regulations, most notably the Americans with Disabilities Act;

- linking medical conditions with the ability to perform essential job tasks safely;

- promoting individualized assessments (as opposed to stipulating categorical exclusionary criteria); and

- clarifying the roles of the medical review officer and the hiring authority.

Fitness-for-duty evaluation is a risk management process; evidence regarding the immediacy, severity, and likelihood of a risk must be considered.

__________________

6Because fire departments are completely decentralized and there is no central authority over local jurisdictions, adoption of the standard cannot be enforced.

7The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine’s guidance is still under development and currently addresses only a few of the planned medical evaluation topics.

However, a determination that a candidate is unable to perform an essential job function because of a disability is not sufficient grounds for an unfit determination. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that reasonable accommodations be considered on a case-by-case basis. Such accommodations could include “restructuring a job by reallocating or redistributing marginal job functions; altering when or how an essential function is performed; permitting use of accrued paid leave or unpaid leave for necessary treatment; modifying examinations, training materials or policies; [and] acquisition or modification of equipment and devices” (Goldberg et al., 2004, p. 10). To evaluate risk and the potential for its mitigation effectively, evaluating physicians need to be familiar with the essential tasks and demands of the job. This requirement necessitates highly detailed position descriptions, particularly if the medical evaluation is outsourced to someone unfamiliar with the job requirements.

Fitness-for-duty evaluations for positions with medical or physical qualifications may be conducted prior to employment (postoffer but preplacement), periodically throughout employment, or on an as-needed basis during employment. In the latter case, such evaluations may be performed when indicated by noted declines or failures in on-the-job performance, following notification by an employee of a change in health status (e.g., a new diagnosis), and after occupational or personal injury or illness that may temporarily or permanently affect an employee’s ability to perform essential job functions safely. The latter case provides a good reason for ensuring that fitness-for-duty and disability management activities are integrated. When an individual who is required to meet medical qualification standards is injured (on or off the job), it is necessary to assess whether the injury will result in permanent, partial, or total disability. In the case of personal illness, extended leave of absence (as permitted under the Family and Medical Leave Act) may also indicate a need for fitness-for-duty evaluation (McMillan, 2013).

When a potentially problematic medical condition is identified during a fitness-for-duty evaluation, a common next step is follow-up with the individual’s treating physician regarding medical records related to management of the condition. If the individual is an employee, he/she may be placed on restricted duty until a determination is made. The amount of time an individual is allowed to remain on limited duty before the case is sent for a determination will likely vary depending on the circumstances. In the military, up to 2 years may pass before someone on limited duty is sent before a medical review board. In the FBI, the average interval is closer to 3 years (Wade, 2013).

There is no standardized clearance process for fitness for duty. The party that makes determinations regarding reasonable accommodation and employability varies across organizations. In some cases, it may be

an occupational health nurse or a medical review officer (internal or outsourced), and in other cases, a medical review board. A medical review board is used by DoD, the FBI (which calls it a Medical Mandates Evaluation Board), and the Secret Service to make determinations on reasonable accommodation and employability. Notably, medical personnel frequently advise such boards, but voting members often are senior line officers and administrative personnel. It is important to note that fitness-for-duty determination is a process that spans human resources and medical responsibilities, and consequently it requires significant coordination between these two entities.

Concerns Regarding Medical Standards and Fitness-for-Duty Evaluations

Throughout its information-gathering process, the committee heard of several concerns regarding fitness-for-duty evaluations from both organization and employee perspectives. Medical and administrative personnel often are concerned about the constraints and liabilities associated with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) or the Rehabilitation Act (for federal agencies). Both laws prohibit discrimination against those with handicaps or disabilities and have significantly impacted fitness-for-duty evaluations. For example, ADA prohibits preemployment evaluations; instead, employers must make a job offer contingent on meeting medical and/or physical qualifications. ADA also requires an employer to consider whether reasonable accommodations can be made for otherwise qualified individuals with disabilities (employees or applicants) without causing undue hardship for agency operations. ADA and the Rehabilitation Act allow employees to sue8 federal agencies if they are removed from their position on medical grounds, and if the agency fails to meet the burden of proof demonstrating that the employee has a disqualifying medical condition and that the condition poses a reasonable probability of substantial harm.9 These concerns were discussed with the committee by FBI Medical Director Dr. David Wade (2013), who noted that to protect the agency from that litigious environment, a solid job task analysis must be implemented with rigor and with a scientific methodology.

Employees are concerned about protection of their personal medical information and the application of fitness-for-duty evaluation for punitive purposes. For example, psychological fitness-for-duty evaluations sometimes

__________________

8The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is the entity responsible for enforcing federal laws against employment discrimination. Equal employment opportunity suits can be filed if employees feel they have been subjected to discrimination based on their disability status (EEOC, 2013).

9Slater v. DHS, 2008 MSPB 73 (U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 2008).

are ordered as a means of dealing with disruptive behavior (Spottswood, 2013). Union representatives from the Border Patrol and the Federal Protective Service expressed concern about the potential for uneven application of fitness-for-duty evaluation based solely on performance (Shigg, 2013; Wright, 2013). However, they agreed that performance-based standards are necessary to ensure that an employee can capably perform on the job when decreased performance is noticed or upon return to duty following an injury. Both also expressed concern that regular medical examinations have led to systematic abuses in the past and do not accurately gauge an employee’s ability to do the job; from the union’s perspective, they stated, regular medical examination would be a nonstarter. Acknowledging psychological fitness-for-duty evaluations as a serious intrusion into employees’ privacy, Dr. Wade (2013) indicated that policies have been put in place at the FBI prohibiting the use of psychological fitness-for-duty evaluations for punitive purposes.

Consistent, transparent processes, detailed position descriptions, and clear policies that set expectations from the start of employment can help address concerns regarding uneven or punitive use of fitness-for-duty evaluations. More important, to build trust and employee engagement, it is critical that fitness-for-duty programs be designed and promoted as part of an overarching strategy for protecting the health and safety of the workforce and ensuring mission success.

Fitness-for-Deployment Evaluations

Given the health and safety risks faced by workers during deployment to remote and/or hazardous settings (e.g., disaster sites), 5 CFR 339 grants federal agencies the authority to require medical evaluation and clearance prior to deployment for disaster response and recovery work and other planned or contingency operations. For some positions, medical clearance may be a condition of employment, but predeployment clearance programs can also be instituted and applied to employees whose positions are not subject to medical standards.10 The Department of State, for example, has a medical clearance program that determines the posts to which members of the Foreign Service can deploy, but does not have medical standards per se (Rosenfarb, 2013). Predeployment evaluations are particularly critical for volunteers or those in positions not subject to medical standards because no prior information on the health status of such individuals may be known. Multiple organizations examined by the committee, including the Texas Task Force One urban search and rescue team (Minson, 2013) and

__________________

10A relevant example at DHS is predeployment screening and clearance for federal employees who volunteer to deploy as part of the DHS Surge Capacity Force.

the American Red Cross (Smith, 2013), conduct predeployment health assessments using questionnaires.

To mitigate health risks to volunteers, the American Red Cross has developed a system for prescreening volunteer responders. During the application process, potential responders provide an overview of their general health by completing a health status record, which is reviewed and compared with a Physical Capacity Grid that details the capacities necessary for successfully performing 30 different basic tasks entailed in relief operations (Smith, 2013). This process determines the type of job a volunteer can do. The American Red Cross also has developed 15 hardship codes describing common physical, environmental, and emotional situations that may affect individuals on a relief operation. Specific assignments that match the responder’s hardship code need to be discussed with the individual before assignment. Medical restrictions also may be applied that limit the types of disasters for which the responder can be deployed (Smith, 2013). Prior to deployment, a preassignment health questionnaire, consisting of yes/no questions, is completed to ensure that health status records are up to date. Any “yes” response is referred to a reviewer who conducts a health interview with the responder; the responder may then be cleared for deployment or denied for medical reasons.

In May 2010, Federal Occupational Health (FOH)11 proposed a similar program for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to address medical clearance for deployment. Viewing deployment readiness as a safety issue as opposed to an accommodation/employability issue, FOH asserted that environmental conditions (including medical infrastructure at disaster sites, power status, accessibility for those with handicaps, expected ambient temperature, and international sites/ability to medically evacuate) should serve as the major determining factors in clearance for specific deployments. FOH proposed a color-coded system as a means of indicating the types of environmental conditions under which a person can deploy based on the results of a health assessment (FOH, 2010). The proposed system takes into account environmental changes that can occur at disaster sites, enabling employees who may not be cleared to deploy under harsh environmental conditions to deploy later when the environment is more suitable to their status. FOH (2010, p. 1) believes that this approach “would satisfy ADA concerns while helping to ensure we are safely using all skilled employees.” To date, such a program has not been implemented.

__________________

11FOH is a nonappropriated agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the largest provider of occupational health and wellness services to the federal government.

Disability Management

Disability management has been defined as “a set of practices designed to minimize the disabling impact of injuries and health conditions that arise during the course of employment” (Hunt, 2009, p. 1). Emerging as a tactic for combating rising workers’ compensation costs, disability management has two primary goals: ensuring continued employment for workers with disabilities and lowering employers’ disability costs (Hunt, 2009). Whereas the provision of workers’ compensation benefits addresses the administrative process of ensuring the financial protection of employees who acquire a disability in the course of performing their job, disability management focuses on preventing the worsening of an injury or illness and turnover for disability reasons (Hunt, 2009). The ultimate goal is to ensure timely reintegration of employees into the workforce (return to work). Since the introduction of this concept in the 1970s, principles of disability management have become increasingly commonplace in existing workers’ compensation programs to help organizations meet these goals.

The Federal Employees’ Compensation Act (FECA) provides workers’ compensation benefits (including wage-loss benefits and vocational rehabilitation) to all civilian federal employees who are injured or become ill in the course of performing their job. The act is administered by the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs (OWCP) in the Department of Labor (DOL), which is the sole entity with the authority to approve or deny a workers’ compensation claim. For traumatic injuries, claims generally are adjudicated by OWCP within 45 days of receipt; this 45-day period is called the continuation-of-pay (COP) period. During this time, employing agencies are responsible for continuing to pay an employee’s salary without requiring the employee to charge sick or annual leave. COP does not apply to occupational disease or recurrence cases (DFEC, 2012). Employing agencies are responsible for advising employees on the process for completing and submitting claims.12

In addition to the administrative aspects of helping injured and ill employees navigate the workers’ compensation claims process, employing agencies are responsible for those aspects of the medical case management process focused on limiting disability and reintegrating injured and recovering employees into the workforce. Support for reintegration may entail providing “light”-duty work when possible or helping to find a new position for employees that are unable to continue carrying out the duties of their old position. OWCP roles in this area include assigning a nurse case manager to ensure provision of appropriate medical care and assist

__________________

12Many agencies have begun using eCOMP, a free, Web-based portal provided by DOL, for the electronic filing of FECA claim forms.

in return to work, providing referral to a medical specialist for a second opinion as necessary, and providing referral for vocational rehabilitation services when an employee is unable to return to his/her previous position (DFEC, 2013).

Return to work can prove difficult under FECA, and more so the longer an employee is away from work. As explained to the committee, FECA “was set up intentionally to be ‘non-adversarial,’ but in return gives enormously generous benefits to the injured worker” (Crowley, 2013), in most cases providing 75 percent of the worker’s date-of-injury salary tax free, with no cap on the amount of compensation or the time for which it is provided. Under FECA, employees have the right to choose their own physician, who determines their ability to work. While an agency can request that DOL refer an injured worker for a second opinion with a physician of DOL’s choosing, it is up to DOL to determine whether doing so is warranted. When a second opinion contradicts the initial determination and is contested by the primary physician, it must then go to an independent medical examiner—a process that can take years (Crowley, 2013). Additionally, following a “total person concept,” if workers have not returned to work and suffer a non-work-related injury, they are eligible to remain on workers’ compensation (Crowley, 2013).

As described earlier, President Obama’s POWER initiative was established to help address the burden of occupational injuries and illnesses on employees, agencies, and the federal government as a whole, in part through return-to-work efforts. The last four of the seven performance areas under POWER relate to workers’ compensation and return to work: increasing the timely filing of workers’ compensation claims, increasing the timely filing of wage-loss claims, reducing lost production day rates, and speeding employees’ return to work in cases of serious injury or illness (Obama, 2010). Although the first two of these areas would appear to be solely administrative in nature, early filing of workers’ compensation claims may translate to earlier intervention to support return-to-work efforts (Tritz, 2013).

The 14 agencies subject to the speeding return to work POWER goal (including DHS) must participate as members in the POWER Return To Work Council, which was chartered to assist OWCP in identifying strategies that could help federal agencies increase return-to-work rates. Council members generally are senior officials with oversight of agency workers’ compensation programs. As part of these efforts, DOL initiated a study on best practices in return to work. The Council reviewed the results of that study, and the following five practices it deemed useful to the

greatest number of agencies were developed into a DOL (2013) guidance document13:

- [have] early contact with injured workers,

- provide modified work positions for short-term injuries,

- communicate within the agency,

- review periodic roll cases and discuss with OWCP, and

- present disability costs to directors and operational managers.

Increasing evidence from the literature shows that early intervention programs can improve return-to-work outcomes for injured workers (Carroll et al., 2010; DOL, 2013; Hoefsmit et al., 2012). In a quantitative study of FECA cases from 2005 to 2010, Maxwell and colleagues (2013, p. x) found that “injured workers who did not return to work quickly (without wage loss relative to their pre-injury earnings) were unlikely to return to work within three years of the reported date of the injury or illness.” The Washington State Department of Labor and Industries found that while most injured workers return from disability within 6 weeks, those who remain on disability at 3 months are already 50 percent more likely to remain on disability at 1 year (Franklin, 2013).

Different agencies have established different methods for ensuring early intervention, including 24-hour hotlines for reporting and the use of agency nurse case managers who initiate contact with an injured or ill employee weeks before a DOL nurse case manager is assigned to the case. Agency nurse case managers may be able to help identify limited-duty positions, which can reduce the COP period and associated workers’ compensation costs (Mitchell, 2013). In Chapter 4, a case study of the Federal Air Marshal Service expands on how agency nurse case managers can also serve to integrate workers’ compensation, medical, safety, and operational programs.

Health Promotion

A medically ready workforce must start with employees who are fit and healthy, both physically and mentally. The process of ensuring a fit and healthy operational workforce begins prior to employment with the setting of expectations and, when appropriate, through physical fitness testing, and continues until retirement through organizational health and wellness programs. For most civilian jobs, participation in health promotion programs is voluntary, but mandatory periodic fitness testing and health

__________________

13Additional information on return to work is available at http://www.dol.gov/odep/returnto-work/index.htm (accessed January 22, 2014).

screening may be justified and legally defensible for certain safety- and security-sensitive positions.14

Elements of Workplace Health Promotion Programs

Workplace health promotion programs often are tailored to the needs of the workforce, and consequently their elements may vary. However, a comprehensive worksite health promotion program is described in Healthy People 2010 (HHS, 2000) as including the following elements:

- health education that focuses on skill development and lifestyle behavior change in addition to information dissemination and awareness building, preferably tailored to employees’ interests and needs;

- supportive social and physical work environments, including established norms for healthy behavior and policies that promote health and reduce the risk of disease, such as worksite smoking policies, healthy nutrition alternatives in the cafeteria and vending services, and opportunities for obtaining regular physical activity;

- integration of the worksite program into the organization’s administrative structure;

- related programs, such as employee assistance programs; and

- screening programs, preferably linked to medical care service delivery to ensure follow-up and appropriate treatment as necessary and to encourage adherence.

Health screening programs, which may include a health risk assessment,15 identify an individual’s health risks based on physiological data (e.g., weight, blood pressure, cholesterol) and lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol intake, exercise, diet). Educational materials, recommendations for lifestyle changes, and implementation plans can then be developed based on those risks, taking into consideration the person’s current life circumstances.

__________________

14Safety- and security-sensitive positions include “positions that involve law enforcement, national security, the protection of life and property, public health or safety, or other functions requiring a high degree of trust and confidence” (Executive Order 12564).

15A health risk assessment is a tool or process for “the assessment of personal health habits and risk factors (which may be supplemented by biomedical measurements of physiologic health); a quantitative estimation or qualitative assessment of future risk of death and other adverse health outcomes; and provision of feedback in the form of educational messages and counseling that describe ways in which changing one or more behavioral risk factors might alter the risk of disease or death” (Soler et al., 2010, p. s238).

TABLE 3-1 Individual- and Organization-Level Impacts of Workplace Health Promotion Programs

| Individual-Level Impacts | Organization-Level Impacts |

|

• Improve fitness, health, and resilience • Decrease disease risk factors (e.g., body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol) • Prevent occupational injuries • Decrease recovery time from injury and illness • Increase job satisfaction |

• Improve mission readiness • Reduce absenteeism and increase productivity • Reduce health-related costs • Reduce turnover for medical reasons • Improve morale |

Although often neglected, mental health promotion is of critical importance. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, an estimated 19.6 percent of U.S. adults suffer from mental illness16 each year (SAMHSA, 2012). Mental health disorders affect the workplace, and the workplace can affect mental health; such disorders are increasingly becoming a cause of reduced productivity, morale, and engagement (Harnois and Gabriel, 2000; IOM, 2013). A 2009 survey of 34,622 employees from 6 American companies found depression (first) and anxiety (fifth) to be among the top five most costly health conditions to employers in terms of annual medical, drug, absenteeism,17 and presenteeism18 costs (Loeppke et al., 2009). The suffering caused by mental disorders can be exacerbated by the additional burden of stigma associated with such disorders, which may prevent affected individuals from seeking help (IOM, 2013). The workplace also can be a major source of stress on employees. Although stress is not considered a mental health disorder, it, too, can impact productivity, morale, and engagement. Employee stress or work-life management and resilience programs, including employee assistance programs, can help employees manage stress and find additional professional help as needed.19

__________________

16The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2012) defines mental illness as “currently or at any time in the past year having had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder (excluding developmental and substance use disorders) of sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria specified within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.”

17Absenteeism is defined as habitual absence from work (IOM, 2005).

18Presenteeism is defined as “on-the-job productivity loss that is illness related; for example, problems such as allergies, asthma, chronic back pain, migraines, arthritis, and depression; also related to productivity loss resulting from caregiving, lack of job satisfaction, and organizational culture” (IOM, 2005).

19For additional information on such programs and their importance, see IOM, 2013.

Benefits of Workplace Health Promotion Programs

Health promotion programs can provide benefits at both the individual and organizational levels (see Table 3-1). At the individual level, physical fitness and a healthy lifestyle can reduce risk factors, such as high body mass index, blood pressure, and cholesterol, associated with chronic disease. These benefits may be especially important for individuals in occupations associated with higher-than-average rates of chronic illness, such as law enforcement. Healthier workers also may be less likely to be injured on the job, and when occupational injuries do occur, they may be less severe and take less time to resolve in healthy individuals (Musich, 2001). At the organizational level, programs that improve the health of the workforce can reduce occupational injury and illness rates and improve productivity by reducing use of sick leave, presenteeism, and turnover for medical reasons (Chapman, 2012). In addition to the reductions in associated costs (e.g., direct health care, workers’ compensation, and disability costs, as well as costs associated with recruitment and training of replacement staff), the end result is high-functioning personnel who are available for mission duties. An additional potential benefit of workplace health promotion programs—one that is less easily measured but equally important—is improved morale: when employees feel valued and taken care of by their employer, job satisfaction and engagement may increase, driving cohesion, loyalty, and esprit de corps (Berry et al., 2011; Lowe et al., 2003).

Financial constraints often are cited as a major barrier to the establishment of workplace health promotion and wellness programs, but such rationales are short-sighted; the return on investment in worker health can more than justify the costs. Return-on-investment estimates vary across studies and are difficult to derive because of the challenges integrating savings data from multiple cost sources (e.g., absenteeism, presenteeism, health care plan costs, and workers’ compensation and disability costs). Nonetheless, a recent meta-analysis by researchers at Harvard University showed that on average, employers saved $3.27 on health care costs for every $1 spent on health promotion programs (Baicker et al., 2010).

The benefits of health promotion programs may be even greater when such programs target employees in jobs that are physically demanding and inherently hazardous. For example, a study by Leffer and Grizzell (2010) showed that establishment of a physician-organized wellness regime at a county fire department was associated with a statistically significant 40 percent reduction in the injury rate relative to the baseline period during the first 9-month intervention period, and by the second intervention year,

this reduction reached 60 percent.20 Firefighters were encouraged to perform 30 minutes of cardiovascular exercise 4 or 5 days a week (using plans developed according to their life circumstances) and received individualized recommendations for addressing health risks identified during counseling or indicated by biometric data.

Workplace Health Promotion Programs in Federal Government Settings

Federal employees can choose from among more than 200 health plans under the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program. Under FEHB law,21 the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) has the authority to negotiate contracts with private health insurance carriers for the entire federal government. As part of this negotiation process, premiums and benefits are set annually, so federal employers cannot offer such incentives as reduced health plan rates to employees participating in health promotion programs. Although OPM has encouraged contracted carriers to offer health promotion and wellness programs, including health risk assessments (OPM, 2011), such programs may vary significantly among carriers and are neither targeted to specific agency employee populations nor integrated into operations at federal worksites—shortcomings that may diminish their effectiveness. Many agencies therefore are supplementing health plan wellness benefits with worksite health promotion programs. These programs may or may not be comprehensive and can be developed and implemented internally or outsourced. For example, some agencies have established interagency agreements with FOH for an integrated health, wellness, and work-life program called FedStrive. In other cases, agencies outsource specific elements of wellness programs, such as employee assistance program services.

Another important difference between federal health promotion programs and their counterparts in private industry relates to data access. Utilization data on health benefits commonly are used to identify top health risks and cost contributors in employee populations; this information can then be used to target interventions and to measure program impacts. Although OPM recently started collecting health care utilization data from carriers and has created a data warehouse as an initial step in the analysis of such data (OPM, 2010), this information currently is not made available

__________________

20The intervention, which was compliant with National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1582 on a Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments, entailed a stress test, collection of biometric data (e.g., body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol), and one-on-one counseling with the consulting physician.

21Public Law 86-382.

to individual federal agencies.22 Thus, federal agencies cannot use metrics related to health care utilization to target interventions or evaluate the performance of prevention programs. However, return-on-investment models may still be developed from estimated savings associated with changes in population risk profiles (Goetzel, 2013).

PROVIDING MEDICAL SUPPORT FOR OPERATIONS

The second pillar of a comprehensive workforce health protection framework is the capability to provide medical support to the workforce during operations. Activities of the employees of an agency or private organization that are conducted in areas remote from conventional medical support raise the issue of how to provide those services in the event of a work-related illness or injury. Operational medicine programs make occupational safety and health and medical services available to workers operating outside conventional workspaces, and they are essential to mission readiness.

The concept of embedding medical support within operational units stems from practices long used by the military to render initial essential stabilizing medical care for battle injuries during the critical few minutes after an injury occurs so as to preserve life and limb. The military also has long recognized the value of having medical support available to prevent and treat disease and nonbattle injuries in order to maintain the operational status of deployed forces. Although battle injuries are the leading cause of deaths in theater, most hospital admissions in deployed operational settings are associated with disease and nonbattle injuries (DoD, 2004). Thus preventive medicine, urgent care, and emergency or tactical medical services are all essential functions of embedded medical support for force sustainment.

The laws and regulations that govern medical practice in civilian settings differ substantially from the authorities that can be granted in the military. Military combat medics such as 18 Deltas23 have wide latitude in rendering medical care, whereas civilian emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics must be licensed and work under a directing physician using approved protocols. Despite these differences, the strategy of

__________________

22In the future, agencies may be able to access separate databases containing their own health care utilization and health risk data (Goetzel, 2013).

2318 Delta is the DoD designation for a U.S. Army Special Forces Medical Specialist, a corpsman who can work independently in austere environments and is trained and authorized to perform advanced procedures and provide care. These personnel receive approximately 1 year of additional training; civilian emergency medical services (EMS) personnel typically do not receive this type of training.

BOX 3-1

Operational Medicine at the Federal

Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

The FBI’s operational medical program is housed within the Office of Medical Services’ Health Care Programs Unit. Originally based on the military special forces model, the program was created to provide support to FBI tactical operations. The FBI currently employs approximately 400 operational medicine personnel, with a ratio of 4:1 basic life support to advanced life support capabilities. FBI operational medicine covers three broad classifications of operations:

- Tactical medical operations: The majority of operational medicine activity supports FBI SWAT teams in all 56 field offices and the Hostage Rescue Team based in Quantico, Virginia.

- Specialized team support: A number of teams require embedded medical treatment capabilities, either by statute or by bureau policy (e.g., teams that collect evidence in hazardous environments; teams that deal with chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear agents; aviation assets that transport subjects by aircraft; technical dive team units).

- Baseline capacities: Over the last 3 years, the FBI has instituted a baseline capacity that mirrors the Department of Defense tactical combat casualty care program through the creation of the Care Under Fire course. All new agents receive this training, and an effort currently is under way to provide this training for the remaining 11,000 FBI Special Agents.

The FBI’s operational medical program operates similarly to a low-call-volume emergency medical services department, dependent on a high level of oversight, simulation, and skills currency training. While the Office of Medical Services provides general program oversight, quality assurance for the program is provided through a variety of means. Credentialing of all operational medical staff is documented and monitored through the use of a centralized electronic credentialing system. All medical encounters are recorded on paper, scanned, and reviewed; in the future, an electronic patient care record may be used for this purpose. Reports that involve an employee become part of the employee’s health record; there are separate repositories for nonemployees, depending on whether they are bystanders or subjects of an investigation (Fabbri, 2013).

embedding medical support within operational units has been adopted in several civilian settings, most notably law enforcement.

Characterizations of operational medicine often center on one of its functions—tactical medicine, defined as “the provision of field medical care during high-risk, extended duration and mission-driven law enforcement operations, often rendered under functionally austere conditions” (Tang,

2013). Such care is similar to that delivered by conventional emergency medical services (EMS) personnel, “modified for the realities of the tactical environment” (Heck and Pierluisi, 2001, p. 403). How this support is provided varies; although some organizations employ personnel whose sole job is to provide medical support during an operation, others utilize law enforcement officers who are able to provide medical support as a collateral duty. Within the federal government, the FBI has developed an extensive program for providing operational medical support to its law enforcement workforce, as outlined in Box 3-1.

Operational medicine is not restricted to the practice of embedding medical practitioners in deployable tactical law enforcement teams, and the elements of an operational medicine program can vary substantially depending on the mission requirements. Like tactical law enforcement teams, rescue teams may have embedded staff to provide medical support to team members and members of the public in emergency situations (see, for example, the description of the National Park Service’s operational medicine program in Box 3-2). Physicians, nurses, and physician assistants stationed in fixed facilities in remote duty outposts may also provide operational medical support. GE Energy, for example, has employees stationed in some of the most remote parts of the world and is responsible for their health and safety (see Appendix E for additional details). In such cases, the distinction between operational medicine and travel medicine as part of an occupational medicine program can become blurred and may be merely a matter of semantics.

Although embedded medical personnel generally are employees of the organization in which they are embedded, fixed facilities and the associated medical staff may be owned by the organization or outsourced (to medical services contractors or through agreements with local health system providers). To achieve their mission, some organizations have created advanced-scope positions requiring additional specialized training to fulfill specific needs; examples include the National Park Service’s Parkmedic and Remote Emergency Medical Responder and the Secret Service’s Emergency Services Specialist (Ross, 2013; Stair, 2013). Despite the variability in the composition of operational medicine programs, the key functions are generally the same—threat assessment, preventive medicine, ambulatory medical support, and emergency medical support.

Medical Threat Assessment

As discussed in relation to occupational safety and health, risk management is a continuous, multistep process designed to reduce risks to health, mission, and property. Management of risk also is important in the context of operational medicine and is achieved in part through medical threat

BOX 3-2

Operational Medicine in the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) manages 9.2 percent of U.S. lands, spanning a wide variety of ecosystems, biomes, and climates. Each year, its 28,000 employees and 120,000 volunteers work not only to conserve and protect these lands but also to protect the 280-300 million visitors to U.S. national parks. To the latter end, the NPS Organic Act (16 USC 1-4) grants NPS the authorities to provide emergency services to visitors and employees. Approximately 75 percent of NPS law enforcement personnel are rangers, whose official job duties include not only law enforcement but also search and rescue and emergency medical services (EMS).

To exercise these authorities, NPS has created an EMS system consisting of 137 EMS programs and 2,286 EMS providers, overseen by four national medical directors that provide overall guidance. Within this system, NPS has created six levels of practice—Emergency Medical Responder, Remote Emergency Medical Responder, Emergency Medical Technician, Advanced Emergency Medical Technician, Parkmedic, and Paramedic—with differing scopes of practice. NPS provides specialized training programs for advanced-scope positions—Remote Emergency Medical Responder and Parkmedic—carried out in high-altitude locations, similar to conditions these personnel will face, and all skills testing is conducted out in the elements. Additionally, NPS operates three medical clinics, providing both emergency care for visitors and employees and routine care for visitors; owns 117 ambulances, 290 intercept vehicles, and more than 4,000 automated external defibrillators; and manages more than 290 memorandums of understanding and memorandums of agreement with local hospitals. Each year, NPS responds to approximately 90,000 calls, about 15,000 of which become patient encounters, providing basic and advanced life support and cardiac, trauma, and medical support, and conducts more than 10,000 patient transports via ground, air, and vessel.

In 2008, NPS implemented an electronic patient care record to create a more evidence-based practice. This system has enabled quality assurance and improvement, refinement of existing and creation of new protocols and procedures, epidemiological surveillance, risk management, and increased notification and communication abilities. NPS also engages in operational leadership—its term for risk management—whereby a green-amber-red model is used to help determine risks associated with operations.

While the program is not congressionally funded, Department of the Interior leadership has found it to be an important, indeed necessary component of the agency’s operations. Each year, money is shifted from other operations to ensure consistent funding. In addition, although technically the government is not allowed to bill, the three NPS clinics function as a Blue Cross Blue Shield preferred provider organization, enabling them to seek cost recovery.

SOURCE: Ross, 2013.

BOX 3-3

Medical Care of In-Custody Individuals

In addition to ensuring the health of those conducting missions and bystanders caught in the mission’s perimeter, medical support during operations extends to ensuring the health and welfare of those taken into custody. This is an ethical imperative, as assuming custody for an individual transfers responsibility for safety from that individual to the agency assuming custody. U.S. legal requirements recognize and safeguard this imperative. Federal courts have held that pretrial medical care, whether in prison or other custody, is required by the Fourteenth Amendment (Wagner v. Bay City, 227 F.3d 316 [5th Circuit 2000]). Further, Mulry and colleagues (2008, pp. 123-124) contend that “the withholding of adequate medical care may be viewed as excessive force, an unconstitutional act in violation of the Fourth Amendment right to be free of unconstitutional seizure.”

NOTE: The definition of operational medicine adopted by the committee encompasses health and medical support provided to persons in DHS care and custody during routine, planned, and contingency operations. However, assessment of health care provided to detainees within Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainment facilities, as well as the adequacy of the facilities themselves, was not considered to be within the scope of this study.

assessment, which involves the creation of a comprehensive mission preplan. The California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (CA POST, 2010, p. 12) recommends that medical threat assessment “be conducted based on available intelligence and information on the nature of the response … [and] incorporated into the tactical plan for the specific mission,” serving as a significant resource for the operations commander. At the committee’s second meeting, Dr. Nelson Tang, Medical Director for ICE and the Secret Service,24 suggested that threat assessment should include examination of a variety of issues, including expected contingencies, expected responses, source of resources, and the destination for casualties resulting from the event (Tang, 2013). Answering such questions prior to an operation will assist in the development of both preventive and responsive medical support plans, protecting the health of the workforce and those affected by operations, including individuals in custody (see Box 3-3).

__________________

24Dr. Tang is Director of the Division of Special Operations and Chief Medical Officer at the Johns Hopkins Center for Law Enforcement Medicine. Several federal agencies, including ICE and the Secret Service, have contracts with this center to provide medical direction for operational medicine programs.

Preventive Medicine and Ambulatory Medical Care

The goal of operational medicine is to support the operational workforce in successful completion of the mission. Operational units often are small, so that illness or injury of members can adversely impact the unit’s mission; thus, the preventive medicine and ambulatory medical care functions are critical to mission success. Preventive medicine functions begin before the mission occurs (e.g., administering predeployment vaccinations, promoting understanding of nutrition issues and sleep/rest cycles), but also continue throughout operations (e.g., food and water hygiene, field sanitation, control of disease vectors). Preventive medicine requirements can be influenced by preoperation threat assessments.

Operational medicine programs often include specialized training in preventive and nonemergency medical care functions because EMS providers traditionally are not trained in these areas. Routine medical problems such as gastrointestinal illnesses, bronchitis, and sports-type injuries (e.g., sprains and strains) usually would be handled through outpatient clinics or hospital visits in traditional work settings, but during operations or when members of the workforce are operating in austere environments, it may be that such resources are absent or cannot be utilized for security reasons.

Emergency Medical Support

Emergency medical support during operations commonly, though not always, is provided by EMTs (basic life support) and paramedics (advanced life support). Notable differences between EMS in conventional settings and during operations include challenging environmental conditions, the length of time until patients can be transferred to definitive care, and in some cases, the requirement to work while “under fire.” Both additional training and expanded protocols are required to provide medical support beyond the conventional role of EMS personnel. Some agencies, including the National Park Service, the FBI, the Secret Service, and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), have developed advanced-capability paramedic positions to ensure the availability of properly trained medical support personnel for the unique challenges and demands associated with their operational missions. This additional training typically includes both simple outpatient treatment skills and more advanced measures to support seriously ill or injured persons when evacuation to a conventional medical facility is delayed. In some programs, all operational team members are trained in “self-care” to provide initial life- and limb-saving treatment prior to evacuation to a definitive hospital facility.

Measurement is critical to understanding organizational needs. However, data collection alone is not enough; the data must be used to drive individual and organizational performance. If impact is not measured, success cannot be distinguished from failure.

Spanning both pillars of the framework outlined in this chapter, measurement and evaluation is essential to developing, implementing, and continuously improving programs designed to address the other eight key functions of an integrated workforce health protection framework (see Figure 3-1). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “a healthy workplace is one in which workers and managers collaborate to use a continual improvement process to protect and promote the health, safety and well-being of workers and the sustainability of the workplace” (Burton, 2010, p. 61). Measurement and evaluation is essential to this process. A system for measurement and evaluation supports multiple key organizational functions, including

- decision making,

- accountability,

- quality improvement, and

- surveillance.

These functions have been termed the “four faces of measurement” (IOM, 2005, p. 151). Processes for measurement and evaluation should be integral to any intervention program, health-related or otherwise. The objective to be met by the measurement will drive the approach to data collection, aggregation, analysis, and reporting.

Needs Assessments

First and foremost, creation and implementation of any new policy or program, including those related to workforce health protection, should be based on a comprehensive understanding of the issues involved; such understanding should be derived from a detailed needs assessment of the current situation. Developing a comprehensive picture of workforce health status and needs will require integration of information from diverse data sets that may include

- human resources data (e.g., absenteeism records or number of resignations);

- occupational health and safety data (e.g., accidents or risk assessments);

- financial data (e.g., the cost of replacing employees who are on long-term disability leave); and

- health data (e.g., common health problems among the workforce) (WHO, 2005).

In addition to enabling the creation of policy and programs based on organizational needs, data derived from such assessments will establish baselines against which program outcomes can be compared to evaluate success and drive continuous improvement.

Approaches to Measurement

The recent IOM report on DHS workforce resilience25 includes the recommendation that DHS “design and implement an ongoing measurement and evaluation process … [which] will support planning, assessment, execution, evaluation, and continuous quality improvement” (IOM, 2013, p. 153). A chapter devoted to measurement and evaluation focuses on the Donabedian (1966) model as an organizing framework for DHS. This model encompasses measurements of structure, process, and outcome and has long served as a standard model for evaluating and assessing health services and quality of care. Structural measures address basic program architecture and critical components, including leadership engagement, policies and procedures, and environmental support; process measures help assess how well the program is being implemented (e.g., utilization and satisfaction); and outcome measures examine the extent to which objectives and goals are achieved within a given period. The present committee identified three primary types of outcome measures that should be monitored in a metric-driven health protection system: health, financial, and productivity. Examples of potential outcomes of interest in each of these categories are provided in Box 3-4.

Within the field of occupational safety and health, a common approach to measurement has focused on lagging and leading indicators. Lagging indicators are retrospective measurements of system performance linked to outcomes; these are the traditional measures of safety performance, such as OSHA statistics and costs (Manuele, 2013). These indicators, however, have a key limitation: “While lagging indicators give information of direct concern to management, the workforce, and the public, they can only be used for improvement after the fact” (NRC, 2009, p. 8). Recent years have seen a shift toward what have been termed leading indicators—in the safety

__________________