2

The DHS Workplace and Health System

Consisting of more than 200,000 men and women working to achieve the overarching mission of ensuring that the U.S. homeland remains safe and secure, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the third largest employer in the federal government, after the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs. This large, complex government agency has faced a mix of political, structural, and managerial challenges since its founding that have hindered its maturation into a cohesive and unified organization. An understanding of the historical context of the department and the difficulties it has previously encountered and continues to face is requisite to visualizing a path toward an integrated capability for workforce health protection. This chapter provides a brief history of the agency and describes, in turn, its mission and current organizational structure, the health and safety challenges faced by its workforce, its health protection mission, and the organization of its health system.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush signed into law the Homeland Security Act of 2002,1 creating a new cabinet-level agency—the Department of Homeland Security—whose purpose was to coordinate and unify national homeland security efforts previously scattered throughout the federal government. The Homeland Security Act brought all or part of 22 different federal departments

__________________

1Public Law 107-296.

and agencies together under the DHS umbrella (see Figure 2-1), making the creation of DHS one of the largest—and certainly the most complex—public-sector mergers in American history (Frumkin, 2003; GAO, 2003; Shenon, 2002). Critical functions of the new agency, organized under directorates established by the Homeland Security Act, included information analysis and infrastructure protection, border and transportation security, emergency preparedness and response, research and development, and management of the DHS enterprise.

From its inception, DHS faced two major challenges: (1) the need to merge a disparate set of agencies in different stages of maturity, some of which had long-established cultures; and (2) the very limited amount of time allowed to plan and accomplish this complex merger. The creation of a new government agency through a merger process requires significant strategic planning and resource investment to ensure that missions are not disrupted, responsibilities and authorities are clearly delineated, and employees do not become disengaged but instead are united by shared values and common missions that are actively communicated by leadership (Frumkin, 2003; Partnership for Public Service and Booz Allen Hamilton, 2011). The Homeland Security Act mandated that DHS be up and running within 60 days of the legislation’s enactment. This mandate left little time to merge basic human resources functions (e.g., hiring and payroll systems), and even less to fully integrate existing, ingrained cultures and processes across components (GAO, 2003). A further complication was that some agencies were disaggregated and distributed among several new agencies within DHS, leading to potential disruption in employees’ sense of organizational identity (GAO, 2003; Partnership for Public Service and Booz Allen Hamilton, 2011). For example, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, previously part of the Department of Justice, was split among three DHS agencies—U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The organizational challenges associated with the creation of DHS were recognized from the outset. “It’s going to take years in order to get this department fully integrated—you’re talking about bringing together 22 different entities, each with a longstanding tradition and its own culture,” said Comptroller General David M. Walker, who directed the Government Accountability Office (GAO), in a 2002 New York Times article written shortly after the decision to create DHS was made (Shenon, 2002). More than 10 years later, challenges related to employee dissatisfaction and integration of DHS management functions remain under GAO scrutiny (GAO, 2012a,b). Although every DHS Secretary has strived toward the vision of a unified enterprise, the vision of “one DHS” has not yet been achieved (McCaul, 2012).

Challenges faced by the newly created department did not originate from within DHS alone. Beyond the organizational complexities, the political context in which DHS operated posed additional difficulties. With the Homeland Security Act, Congress sought to streamline homeland protection efforts, but the legislative branch failed to follow suit by streamlining its own oversight functions (NPR, 2010). Although House and Senate Committees on Homeland Security were created and have primary jurisdiction over DHS, many of the components that were assimilated into the new department had previously been associated with other committees, none of which were willing to relinquish jurisdiction and authority (Partnership for Public Service and Booz Allen Hamilton, 2011). In 2004, 88 committees and subcommittees had oversight over DHS (Kean and Hamilton, 2004). Since then, rather than being consolidated, that number has grown to more than 100 (NPR, 2010). In addition to the significant amount of time required to respond to so many congressional committees (for example, more than 5,000 briefings were held in 2007-2008 [NPR, 2010]), the manifold and sometimes opposing direction from the various committees, subcommittees, and caucuses has made it difficult for DHS to identify key priorities to guide programmatic and budgetary decision making. The report of the 9/11 Commission cites the fragmented nature of congressional oversight as one of the largest obstacles to the successful development of DHS (Kean and Hamilton, 2004).

The events of September 11, 2001, irrevocably altered the U.S. approach to homeland protection. The threat of attack on U.S. soil from sources both domestic and foreign necessitated a wide-ranging but coordinated homeland security team to complement the armed forces that had served as the cornerstone of the U.S. defensive strategy. With recognition of the broader nature of threats to U.S. security, the operational landscape for the homeland security workforce has evolved. Securing the homeland against 21st-century threats goes beyond preventing terrorist attacks to include preparing and planning for emergencies; investing in strong early event recognition, response, and recovery capabilities; and protecting the nation’s systems for trade and travel. Box 2-1 presents DHS’s multifaceted mission statement.

The breadth of the DHS mission is reflected in the diversity of its component agencies. The five core DHS missions described in Box 2-1 are carried out by the department’s seven operating component agencies (CBP,

BOX 2-1

Department of Homeland Security Missions

- Prevent terrorism and enhance security: Protecting the American people from terrorist threats is our founding principle and our highest priority. The Department of Homeland Security’s counterterrorism responsibilities focus on three goals: (1) Prevent terrorist attacks; (2) Prevent the unauthorized acquisition, importation, movement, or use of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear materials and capabilities within the United States; and (3) Reduce the vulnerability of critical infrastructure and key resources, essential leadership, and major events to terrorist attacks and other hazards.

- Secure and manage our borders: The Department of Homeland Security secures the nation’s air, land, and sea borders to prevent illegal activity while facilitating lawful travel and trade. The department’s border security and management efforts focus on three interrelated goals: (1) Effectively secure U.S. air, land, and sea points of entry; (2) Safeguard and streamline lawful trade and travel; and (3) Disrupt and dismantle transnational criminal and terrorist organizations.

- Enforce and administer our immigration laws: The department is focused on smart and effective enforcement of U.S. immigration laws while streamlining and facilitating the legal immigration process.

- Safeguard and secure cyberspace: The department has the lead for the federal government for securing civilian government computer systems and works with industry and state, local, tribal, and territorial governments to secure critical infrastructure and information systems. The department works to: analyze and reduces cyber threats and vulnerabilities; distribute threat warnings; and coordinate the response to cyber incidents to ensure that our computers, networks, and cyber systems remain safe.

- Ensure resilience to disasters: The Department of Homeland Security provides the coordinated, comprehensive federal response in the event of a terrorist attack, natural disaster or other large-scale emergency while working with federal, state, local, and private sector partners to ensure a swift and effective recovery effort. The department builds a ready and resilient nation through efforts to bolster information sharing and collaboration; provide grants, plans, and training to our homeland security and law enforcement partners; and facilitate rebuilding and recovery along the Gulf Coast.

SOURCE: http://www.dhs.gov/our-mission (accessed January 17 2014).

USCIS, the U.S. Coast Guard,2 the Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], ICE, the U.S. Secret Service, and the Transportation Security

__________________

2The Coast Guard’s primary missions are domestic in nature (e.g., drug interdiction, maritime law enforcement, environmental stewardship, search and rescue), but the Coast Guard also is one of the five armed forces of the United States. During wartime or at the pleasure of the President, the Coast Guard can be called upon to operate as a component service of the

BOX 2-2

Brief Descriptions of the Missions of Selected DHS

Component and Subcomponent Agencies

Components:

- Customs and Border Protection: Keeping terrorists and their weapons out of the United States, securing the nation’s borders, and facilitating lawful international trade and travel while enforcing hundreds of U.S. laws and regulations, including immigration and drug laws.

o Office of Border Patrol: Securing the nation’s border from the illegal entry of goods and people outside of officially established entry points.

o Office of Field Operations: Enforcing customs, duties, and tariffs to support the lawful operation of official ports of entry and to prevent all types of smuggling and unauthorized entry.

o Office of Air & Marine: Operating an extensive network of aviation and marine interdiction and surveillance assets to supplement and support the work of other Customs and Border Patrol operations.

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement: Promoting homeland security and public safety through the criminal and civil enforcement of federal laws governing border control, customs, trade, and immigration.

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: Helping to realize America’s promise as a nation of immigrants by providing accurate and useful information as needed, granting immigration and citizenship benefits, promoting awareness and understanding of citizenship, and ensuring the integrity of the nation’s immigration system.

- U.S. Coast Guard: Safeguarding U.S. maritime interests in the heartland, in the nation’s ports, at sea, and around the globe. By law, the Coast Guard has 11 missions: ports, waterways, and coastal security; drug interdiction; aids to navigation; search and rescue; living marine resources; marine safety; defense readiness; migrant interdiction; marine environmental protection; ice operations; and other law enforcement.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency: Supporting citizens and first responders to ensure that the nation works together to build, sustain, and improve its capability to prepare for, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate all hazards.

- U.S. Secret Service: Safeguarding the nation’s financial infrastructure and payment systems to preserve the integrity of the economy, and protecting national leaders, visiting heads of state and government, designated sites, and national special security events.

- Transportation Security Administration: Protecting the nation’s transportation systems to ensure freedom of movement for people and commerce.

Administration [TSA]) and 18 supporting offices and directorates, each with distinct roles (see Box 2-2). The department is led by a number of

__________________

U.S. Department of the Navy, and authority over its forces can be transferred to the Department of Defense.

o Federal Air Marshal Service: Promoting confidence in the nation’s civil aviation system through the effective deployment of Federal Air Marshals to detect, deter, and defeat hostile acts targeting U.S. air carriers, airports, passengers, and crews.

Major Headquarters Activities

- Science and Technology Directorate: Strengthening America’s security and resiliency by providing knowledge products and innovative technology solutions for the homeland security enterprise.

- National Protection and Programs Directorate: Leading the national effort to protect and enhance the resilience of the nation’s physical and cyber infrastructure.

o Federal Protective Service: Ensuring the physical security of the government’s public buildings and assets.

- Office of Health Affairs: Advising, promoting, integrating, and enabling a safe and secure workforce and nation in pursuit of national health security.

- Office of Intelligence and Analysis: Equipping the homeland security enterprise with the intelligence and information needed to keep the homeland safe, secure, and resilient.

- Domestic Nuclear Detection Office: Implementing domestic nuclear detection efforts for a managed and coordinated response to radiological and nuclear threats, as well as integrating federal nuclear forensics programs and coordinating the development of the global nuclear detection and reporting architecture, with partners from federal, state, local, and international governments and the private sector.

- Federal Law Enforcement Training Center: Training those who protect the homeland by serving as an interagency law enforcement training organization for 91 federal agencies and providing services to state, local, tribal, and international law enforcement agencies.

- Management Directorate*: Ensuring that DHS employees have well-defined responsibilities and that managers and their employees have efficient means of communicating with one another, with other governmental and nongovernmental bodies, and with the public they serve.

______________

*The Management Directorate includes the DHS Chief Administrative Services Officer, Chief Financial Officer, Chief Human Capital Officer, Chief Information Officer, Chief Procurement Officer, and Chief Security Officer.

SOURCES: www.cbp.gov; www.ice.gov; www.uscis.gov; www.uscg.mil; www.fema.gov; www.secretservice.gov; www.tsa.gov; www.dhs.gov; www.fletc.gov.

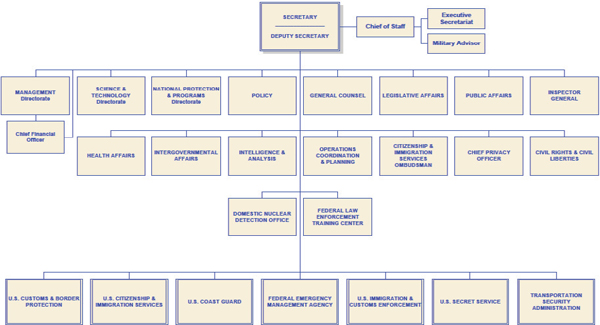

presidentially appointed and Senate-confirmed leaders, including the DHS Secretary, Deputy Secretary, Under Secretaries, Assistant Secretaries, and component agency heads. Figure 2-2 shows the current organization of the DHS superstructure.

FIGURE 2-2 DHS organizational chart.

SOURCE: http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/dhs-orgchart.pdf (accessed January 17, 2014).

Table 2-1 shows the distribution of the more than 200,000 DHS employees by component agency. Notably, these numbers do not include contracted staff, whose number has been difficult to track. In 2011, approximately 100,000 contractors were estimated to work for DHS—about half the size of the department’s federal workforce (Reilly, 2011). This heavy dependence on a contractor workforce has raised concerns that

TABLE 2-1 Workforce Size by Component (as of June 2013)

| Component | Number of Employees | Additional Information |

| Transportation Security Administration | 64,147 | |

| Customs and Border Protection | 59,436 | |

| U.S. Coast Guard | ~46,581 | Includes approximately 38,000 active-duty personnel, but not the 8,000 reservists and 35,000 auxiliary (civilian volunteer) Coast Guard personnel. |

| Immigration and Customs Enforcement | 19,774 | |

| Federal Emergency Management Agency | 15,081 | Only 4,925 are permanent full-time employees. The vast majority of the FEMA workforce are reservists, nonpermanent full- and part-time employees available to assist in disaster response and recovery. |

| U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services | 12,430 | |

| U.S. Secret Service | 6,524 | |

| DHS Headquarters | 3,281 | |

| National Protection and Programs Directorate | 2,801 | |

| Federal Law Enforcement Training Center | 1,116 | |

| Office of the Inspector General | 731 | |

| Science and Technology Directorate | 466 | |

| Domestic Nuclear Detection Office | 112 |

SOURCE: OPM, 2013.

contractors may be performing inherently governmental functions3 and also poses considerable management challenges. For example, special attention must be paid to ensuring that contractors meet minimum requirements set by the department (e.g., fitness-for-duty standards). Although contracted companies are responsible for the health and safety of their workers, DHS still has the responsibility of providing them with a safe and healthful work environment. Specific issues related to contracted medical providers are discussed in Chapter 6 of this report.

HEALTH AND SAFETY CHALLENGES AT DHS

With its heavy focus on securing the nation’s borders and protecting critical infrastructure, DHS often is referred to as a “guns, guards, and gates” organization—about half of its workforce is made up of law enforcement and security personnel.4 The number of law enforcement officers at DHS (~50,000) is only slightly smaller than the number employed by the Department of Justice (GAO, 2006); these two departments account for the vast majority of the federal law enforcement workforce in the United States. Within DHS, law enforcement officers are employed by nearly every operational component but are concentrated primarily within CBP (largely the Office of Border Patrol and the Office of Field Operations), followed by ICE. One headquarters component, the National Protection and Programs Directorate, also has a notable law enforcement workforce. The Federal Protective Service, located within the National Protection and Programs Directorate, employs approximately 900 law enforcement security officers, criminal investigators, police officers, and support personnel, in addition to 15,000 contracted guard staff, to secure federal buildings and safeguard their occupants (DHS, 2013a).

The other major operational arm of the DHS workforce comprises rescue and emergency response personnel, employed primarily by FEMA and the Coast Guard. The size of the emergency response workforce is variable. FEMA’s permanent full-time staff is relatively small (~5,000), but its workforce can swell considerably through the activation of its approximately 10,000 reservists5 in the event of a disaster (OPM, 2013). The

__________________

3In a letter to then Secretary Napolitano, Senators Collins and Lieberman voiced such concern, stating that “the sheer number of DHS contractors currently on board again raises the question of whether DHS itself is in charge of its programs and policies, or whether it inappropriately has ceded core decisions to contractors” (HSGAC, 2010).

4TSA’s approximately 50,000 transportation security officers, although considered security personnel for the purposes of this report, are not classified as federal law enforcement officers and do not carry weapons on duty. Contracted security personnel are not included in this statistic.

5Temporary federal employees, previously called disaster assistance employees.

Coast Guard is a hybrid organization that has a strong search-and-rescue function but also has responsibility for carrying out domestic (maritime) law enforcement operations. A comparatively small but essential population within the DHS operational workforce is made up of those working in the area of critical infrastructure protection (e.g., cyber security and protection of financial systems). Nonoperational members of the DHS workforce include policy personnel, who often hold high-level security clearances, and mission support personnel.

The DHS workplace is as varied as its workforce, with employees stationed in all 50 states and more than 75 countries (Napolitano, 2013). Many of those employees operate in the field on a daily basis, often in austere and remote environments, facing a variety of unavoidable hazards while carrying out their missions. Others can be deployed with relatively little notice to areas where working conditions may be more hazardous or medical services less accessible than is the case at their usual workplace (e.g., overseas or a disaster site). From Border Patrol stations stretching across the vast and hazardous expanse of the southwest U.S. border to Coast Guard stations in the remote Alaskan arctic, DHS employees can be found in some of the most challenging work environments, contending with extreme temperatures, dangerous wildlife, communicable diseases, and armed assailants.

DHS’s large operational workforce poses significant challenges for agency programs designed to keep workers healthy and safe. In contrast to more traditional or fixed workplaces, where hazards often can be eliminated through effective planning, engineering, and constant vigilance, threats to employee health and safety are inherent to many operational environments and can be controlled only to a limited extent. In addition to the work environment, demands of the job themselves can present health risks. In addition to predictable risks from firearms and vehicle collisions, research has demonstrated that jobs such as law enforcement are associated with a higher prevalence of suicide, cardiovascular disease, depressive symptoms, and metabolic disorder than are many other occupations (Hartley et al., 2007; Rajaratnam et al., 2011; Violanti et al., 1996, 2008, 2009).

Cultures ingrained in certain workforce populations can add to these already formidable challenges. For example, law enforcement personnel may avoid help-seeking behavior (e.g., utilizing employee assistance programs and other counseling services) because of perceived stigma, and high-level policy personnel may do the same because of concern about losing their security clearance (IOM, 2012, 2013). The critical nature of the DHS mission requires that certain levels of unavoidable risk be accepted. Still, the department cannot fulfill its mission requirements unless those who operate daily on its front lines function at a high level, and it must therefore find

ways to ensure that the health, safety, and resilience of its most valuable asset are protected to the extent possible.

THE HEALTH PROTECTION MISSION AT DHS

Health protection functions at DHS can be divided into two general categories—externally focused public health activities to protect the American public against weapons of mass destruction, natural disasters, and other health threats; and internally focused activities to protect the health of the DHS workforce and those in their care. As this committee was tasked with evaluating the latter set of functions, the following sections focus primarily on the health protection mission at DHS as it pertains to the DHS workforce and the department’s direct health services, both past and present.

Creation of a Centralized Focus on Health

In 2004, then Secretary Tom Ridge requested a review of DHS’s medical readiness responsibilities and capabilities. The subsequent report (Lowell, 2005) indicated that workforce health programs were fragmented and implemented unevenly across components, lacked visibility and authority, and were inadequately staffed. Specific deficiencies noted in the report included communication and training on occupational safety and health policy and programs, use of and training in personal protective equipment, medical support for field operating units, training in self-aid/buddy care, and evaluations for fitness to deploy. To address these deficiencies, the report called for the development of a centralized medical infrastructure to coordinate the department’s medical activities, serve as a medical point of contact for the DHS Secretary and other federal agencies, facilitate medical risk communications, develop medical policy and oversight mechanisms, and promote consideration of medical issues in operational planning and decision making. The report recommended further that an organizational entity be given responsibilities and resources for oversight of a DHS workforce health protection program encompassing occupational safety and health, medical monitoring, and medical support to field operating units. While progress has been made toward the development of a centralized medical infrastructure with the creation of OHA and the CMO position, the recommended alignment of occupational safety and health and medical programs was never implemented, and the committee found that many of the deficiencies noted in that report have yet to be addressed.

Creation of the DHS Chief Medical Officer Position

In 2005, shortly after succeeding Ridge, Secretary Michael Chertoff undertook a second-stage review of DHS—a systematic evaluation of the department’s operations, policies, and structures. Among the findings of this review was the need to focus and consolidate the department’s preparedness efforts. To this end, Secretary Chertoff (2005) announced the creation of a Chief Medical Officer (CMO) position. This position was codified by the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006,6 which outlined five primary responsibilities for the CMO:

- to serve as principal advisor to the DHS Secretary and the head of FEMA on medical and public health issues;

- to coordinate DHS’s biodefense activities;

- to ensure internal and external coordination of DHS’s medical preparedness and response activities, including training, exercises, and equipment support;

- to serve as the primary DHS point of contact on medical and public health issues for governments (federal, state, local, and tribal), the medical community, and all other relevant parties within and outside of DHS; and

- to discharge DHS’s responsibilities related to Project BioShield7 (in coordination with the Under Secretary for Science and Technology).

Creation of the Office of Health Affairs

On January 18, 2007, Secretary Chertoff announced the creation of the Office of Health Affairs (OHA) as part of a larger departmental reorganization. The mission of the new office was to serve as DHS’s principal authority for all medical and public health matters, working with other federal agencies and the private sector to take the lead in the DHS role in “developing, supporting, measuring and refining a scientifically rigorous, intelligence-based medical and biodefense architecture to ensure the public health and medical security of our Nation” (Krohmer, 2007). One of the goals for the new office was to ensure that DHS employees are supported by an effective occupational safety and health program. Although such a program was already being administered from the Office of Safety and

__________________

6Public Law 109-295.

7Project BioShield was a 2004 legislated initiative to develop and make available medical countermeasures (e.g., drugs and vaccines) to defend against chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear attacks.

Environmental Programs,8 OHA’s Office of Component Medical Services9 sought to integrate occupational medicine into the existing program and act as a high-level advocate for safety and health issues. In the current organization of OHA, these functions now fall under the Workforce Health and Medical Support Division.

In 2008, Secretary Chertoff further clarified the authority of the DHS CMO by issuing Delegation #5001, Delegation to the Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs and Chief Medical Officer (see Appendix B) (DHS, 2008). That document vested authority in the CMO for exercising oversight over all medical and public health activities of DHS, including but not limited to

- leading the department’s biodefense activities;

- providing medical guidance for the department’s personnel programs, including fitness-for-duty and return-to-work programs, drug testing, health screening and monitoring, preplacement evaluations, immunizations, medical surveillance, medical record keeping, deployment physicals, and medical exam protocols;

- performing medical credentialing and developing quality assurance and clinical policy, requirements, standards, and metrics for all human and veterinary clinical activities within DHS;

- ensuring an effective coordinated medical response to natural or manmade disasters or acts of terrorism;

- leading the development of strategy, policy, and requirements for any DHS funding mechanisms for medical and public health activities; and

- entering into agreements and contracts to discharge the authorities, duties, and responsibilities of OHA.

The Current Health Protection Mission at DHS

The focus of OHA, mirroring that of the entire department, has shifted from protection against acts of terrorism to a broader all-hazards approach. This shift is reflected in OHA’s mission and goals. Today, OHA’s mission is “to advise, promote, integrate, and enable a safe and secure workforce and nation in pursuit of national health security” (DHS, 2013b). Notably

__________________

8Initially, a departmental occupational safety and health program, as required by presidential executive order, was located in the Office of Administration under the oversight of the Under Secretary for Management, who was the Designated Agency Safety and Health Official.

9In its initial configuration, OHA was divided into three offices—Weapons of Mass Destruction and Biodefense, Medical Readiness, and Component Services—with the first two being focused on public health activities relating to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear attacks and natural disasters. The Office of Component Services was responsible for medical oversight of health care delivery throughout the department.

BOX 2-3

OHA Goals and Strategic Objectives

Goal 1: Provide expert health and medical advice to DHS leadership

Strategic Objective 1.1 Anticipate, inform, and advise the Secretary, FEMA Administrator and other DHS officials on medical and health issues

Strategic Objective 1.2 Provide the Department with expertise in medicine, public health, veterinary medicine, toxicology, and biological sciences

Strategic Objective 1.3 Provide policies and guidance to DHS Components regarding the quality and standards of health care offered by DHS

Goal 2: Build national resilience against health incidents

Strategic Objective 2.1 Mitigate consequences of biological and chemical events through early detection

Strategic Objective 2.2 Enhance preparedness through capabilities development

Strategic Objective 2.3 Inform national planning and policy

Strategic Objective 2.4 Provide situational awareness of health incidents, specifically unusual biological events

Strategic Objective 2.5 Engage international partners in focused health security priorities

Goal 3: Enhance national and DHS medical first responder capabilities

Strategic Objective 3.1 Facilitate the integration of the emergency medical services (EMS) community into federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal disaster preparedness activities

Strategic Objective 3.2 Provide standards and guidelines to DHS EMS providers for delivery of EMS services

Goal 4: Protect the DHS workforce against health threats

Strategic Objective 4.1 Unify and standardize occupational health and workforce protection activities across the department

Strategic Objective 4.2 Build resilience across the DHS workforce

Strategic Objective 4.3 Support DHS operational medical forces

SOURCE: OHA Strategic Framework (DHS, 2010).

absent from OHA’s current mission and goals is the strong language that previously described its role as the “principal medical authority” for DHS.

A 2010 strategic framework released by OHA defines four overarching goals, each with strategic objectives, to help guide its mission (see Box 2-3). Although Goal 2 is focused solely on the externally facing public health activities of OHA, the other three goals relate to the medical infrastructure within DHS and therefore were of interest to this committee. In addressing its task, the committee sought to examine the current capability of DHS to achieve these goals.

ORGANIZATION OF THE DHS HEALTH SYSTEM

Although DHS headquarters has an oversight and facilitation role, management and administration of occupational health and operational medicine programs is decentralized such that each component agency controls its own organizational structure and assets. The subsections below describe the organizational structure of the DHS health system at the headquarters and component levels. Component-specific descriptions of health program organization, including organizational charts, are included in Appendix A.

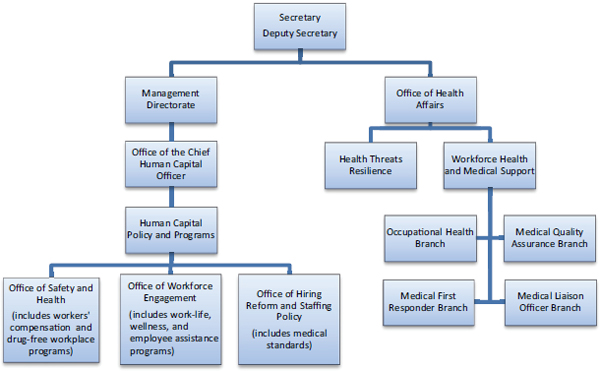

Headquarters Level

Although the 2008 Delegation to the Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs and Chief Medical Officer assigned the CMO authority for exercising oversight over all medical and public health activities of DHS, responsibility for workforce health protection functions at the department level is divided between two mission support offices: OHA and the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer (OCHCO), with the latter being located within the Management Directorate. OHA, led by the CMO, consists of two divisions: (1) Health Threats Resilience, which focuses on externally facing public health activities such as BioWatch; and (2) Workforce Health and Medical Support. The latter division is further divided into four branches: the Occupational Health Branch, which focuses on the medical aspects of department-wide occupational health, including medical countermeasures, medical standards, implementation of a DHS-wide electronic health information system, and workforce resilience; the Medical Quality Assurance Branch, which provides medical guidance, credentialing, and quality assurance standards; the Medical First Responder Coordination Branch, which facilitates operational medical support for mission-essential personnel, coordinates medical first responder readiness for catastrophic incidents, and represents DHS to the medical first responder community (DHS, 2013c); and the Medical Liaison Officer (MLO) Branch, which was created only recently and supports the MLO program, and was implemented to facilitate coordination between OHA and the components (Patrick, 2013). The MLO program is discussed further in Chapter 4.

Several key health functions that intersect with personnel programs, including occupational safety and health, workers’ compensation, return-to-work/disability management, and health promotion, are being administered and overseen by the Chief Human Capital Officer, who is the DHS Designated Agency Safety and Health Official. The division of occupational health functions between OHA and OCHCO is described in Table 2-2. As shown in Figure 2-3, the Designated Agency Safety and Health Official

TABLE 2-2 Division of Responsibilities for Occupational Health Activities Between the Office of Health Affairs and the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer

| Responsibility | Office of Health Affairs (OHA) | Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer (OCHCO) |

| Occupational safety and health | OHA provides guidance and support for medical aspects of DHS health and safety programs, and consults as needed for accident investigations. | OCHCO leads the development of policy, standards, requirements, and metrics related to DHS health and safety programs. It also conducts trend analyses and evaluations of component agency programs. |

| Workers’ compensation/return to work | Despite having delegated oversight authority for return-to-work programs, OHA is currently inactive in this area. OHA is not involved in the administration of workers’ compensation programs. | The DHS Workers’ Compensation Program Manager and Policy Advisor within OCHCO provides guidance to component agencies on workers’ compensation programs, and recently initiated a contracted DHS workers’ compensation medical case management program to facilitate return to work. |

| Fitness for duty | OHA has responsibility for developing medical standards and recently established a medical review board to discuss standards and potentially to adjudicate cases. To date, OHA has issued no fitness-for-duty standards. Although a process was initiated to develop a “gun carrier” minimum medical standard, the process stalled and has yet to be revisited. | All medical standards for employment that must go to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management for approval go through the Office of Hiring Reform and Staffing Policy within OCHCO. |

| Wellness and resilience | OHA created the DHSTogether program in 2009 in response to a charge from Secretary Napolitano to develop an employee resilience program. This program has been reviewed elsewhere (IOM, 2012, 2013). | Human Capital Policy and Program staff provide information and guidance to component agencies on the implementation of wellness programs and are in the process of issuing a policy on baseline requirements for such programs. |

FIGURE 2-3 Organization of DHS headquarters health functions.

NOTES: There are six primary offices within Human Capital and Policy Programs, but only those with health-related functions are included in this figure. The Chief Human Capital Officer serves as the Designated Agency Safety and Health Official, and the Chief Medical Officer leads the Office of Health Affairs.

and CMO are in different reporting chains that do not intersect until the Deputy Secretary level.

Several headquarters-level directorates and centers have health and medical staff or programs specific to their needs. The National Protection and Programs Directorate’s Human Capital Office has both medical (e.g., fitness-for-duty) and occupational safety and health programs. The Science and Technology Directorate has an Environmental Safety and Health Branch, and one of its facilities, Plum Island Animal Disease Center, has its own fire department that is integrated with the local emergency medical services system. The Federal Law Enforcement Training Center has an Environmental and Safety Division, an Office of Organizational Health, and health clinics at each training center that provide services to students and staff.

Component Agencies

Component agencies have evolved different organizational structures to support occupational health and operational medicine functions. Described in more detail in Appendix A, workforce health protection programs are segregated in some components and centralized in others, with

organizational placement differing across the components. Although occupational health programs tend to fall within organizational units dealing with management issues (often human capital or administration), operational medicine programs at DHS are divided between management units and operational units, such as the Office of Border Patrol at CBP or Response and Recovery at FEMA. Even when all health and medical programs fall within a single management unit, programs often are segregated among different offices, and, with the notable exception of the Coast Guard, the committee found that generally no single person has sole responsibility for oversight and coordination of all health, safety, and medical programs. The implications of this segregation of health programs within and across agencies for the integration of health protection functions at DHS are discussed further in Chapter 4.

Chertoff, M. 2005. The Secretary’s second-stage review: Re-thinking the Department of Homeland Security’s organization and policy direction. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Homeland Security. 109th Congress. July 14, Washington, DC.

DHS (Department of Homeland Security). 2008. Delegation to the Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs and Chief Medical Officer. Delegation Number 5001. Washington, DC: DHS.

DHS. 2010. The Office of Health Affairs strategic framework. Washington, DC: DHS.

DHS. 2013a. About the Federal Protective Service. http://www.dhs.gov/about-federal-protective-service (accessed December 12, 2013).

DHS. 2013b. Office of Health Affairs. http://www.dhs.gov/office-health-affairs (accessed November 11, 2013).

DHS. 2013c. Workforce health and medical support division. https://www.dhs.gov/workforce-health-and-medical-support-division (accessed November 12, 2013).

Frumkin, P. 2003. Making public sector mergers work: Lessons learned. Washington, DC: IBM Center for the Business of Government.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2003. Major management challenges and program risks: Department of Homeland Security. GAO-03-102. Washington, DC: GAO.

GAO. 2006. Federal law enforcement: Survey of federal civilian law enforcement functions and authorities. GAO-07-121. Washington, DC: GAO.

GAO. 2012a. Continued progress made improving and integrating management areas, but more work remains. GAO-12-1041T. Washington, DC: GAO.

GAO. 2012b. Department of Homeland Security: Taking further action to better determine causes of morale problems would assist in targeting action plans. GAO-12-940. Washington, DC: GAO.

Hartley, T. A., J. M. Violanti, D. Fekedulegn, M. E. Andrew, and C. M. Burchfiel. 2007. Associations between major life events, traumatic incidents, and depression among Buffalo police officers. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health 9(1):25-35.

HSGAC (U.S. Senate Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee). 2010. Senators Lieberman, Collins astounded DHS contract workers exceed number of civilian employees. http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/minority-media/senators-lieberman-collins-astounded-dhs-contract-workers-exceed-number-of-civilian-employees (accessed January 27, 2014).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. Building a resilient workforce: Opportunities for the Department of Homeland Security, workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. A ready and resilient workforce for the Department of Homeland Security: Protecting America’s front line. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kean, T. H., and L. H. Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 commission report: Final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. Executive summary. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Krohmer, J. R. 2007. DHS Office of Health Affairs: Overview briefing. Washington, DC: DHS.

Lowell, J. A. 2005. Medical readiness responsibilities and capabilities: A strategy for realigning and strengthening the federal medical response. Washington, DC: DHS. http://webharvest.gov/congress110th/20081217150105/http://oversight.house.gov/documents/20051209101159-27028.pdf (accessed January 16, 2014).

McCaul, M. T. 2012. Building one DHS: Why can’t management information be integrated? U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Management. 112th Congress, March 1, Washington, DC.

Napolitano, J. 2013. The President’s FY 2014 budget request for the Department of Homeland Security. U.S. House of Representatives, House Committee on Homeland Security. 113th Congress. April 18, Washington, DC.

NPR (National Public Radio). 2010. Who oversees homeland security? Um, who doesn’t? http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=128642876 (accessed November 11, 2013).

OPM (Office of Personnel Management). 2013. Employment cubes—June 2013. http://www.fedscope.opm.gov/employment.asp (accessed November 11, 2013).

Partnership for Public Service and Booz Allen Hamilton. 2011. Securing the future: Management lesson of 9/11. http://www.boozallen.com/media/file/Management_Lessons_of_9-11.pdf (accessed December 13, 2013).

Patrick, R. 2013. Overview of the Medical Liaison Officer program and operational medicine. Presentation at IOM Committee on DHS Occupational Health and Operational Medicine Infrastructure: Meeting 1, March 5, Washington, DC.

Rajaratnam, S. M., L. K. Barger, S. W. Lockley, S. A. Shea, W. Wang, C. P. Landrigan, C. S. O’Brien, S. Qadri, J. P. Sullivan, and B. E. Cade. 2011. Sleep disorders, health, and safety in police officers. Journal of the American Medical Association 306(23):2567-2578.

Reilly, S. 2011. Whoops: Estimate on number of DHS contract employees off by 100,000 or so. http://blogs.federaltimes.com/federal-times-blog/2011/04/11/whoops-estimated-number-of-dhs-contract-employees-off-by-at-least-100000 (accessed December 15, 2013).

Shenon, P. 2002. Threats and responses: The reorganization plan; establishing new agency is expected to take years and could divert it from mission. New York Times, November 20.

Violanti, J. M., J. E. Vena, and J. R. Marshall. 1996. Suicides, homicides, and accidental death: A comparative risk assessment of police officers and municipal workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 30(1):99-104.

Violanti, J. M., L. E. Charles, T. A. Hartley, A. Mnatsakanova, M. E. Andrew, D. Fekedulegn, B. Vila, and C. M. Burchfiel. 2008. Shift-work and suicide ideation among police officers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 51(10):758-768.

Violanti, J. M., C. M. Burchfiel, T. A. Hartley, A. Mnatsakanova, D. Fekedulegn, M. E. Andrew, L. E. Charles, and B. J. Vila. 2009. Atypical work hours and metabolic syndrome among police officers. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health 64(3):194-201.