3

Oversight of Gene Transfer Research

In any area of biomedical research, many scientific and regulatory challenges stand between promising ideas generated from basic research and the approval of a therapeutic product. Among these emerging technologies, gene transfer research, in particular, stands out as a highly regulated area of scientific investigation. Because clinical gene transfer trials involve both recombinant DNA (rDNA) and human subjects, investigators must submit clinical gene transfer protocols to the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (RAC) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at the federal level and institutional review boards (IRBs) and institutional biosafety committees (IBCs) at the local level before human subjects can be enrolled. This chapter summarizes the current regulatory, oversight, and policy context of this area of research in the United States with a focus on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the RAC, followed by a briefer consideration of the roles of FDA, IRBs, and IBCs, noting relationships among the oversight bodies.

NIH AND THE RECOMBINANT DNA ADVISORY COMMITTEE

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the rapid progression of the concepts and technology that led to the first intentional creation of rDNA molecules (Berg and Mertz, 2010). The RAC was established by then–NIH Director Donald Frederickson in 1974 in response to scientific, public, and political concerns about the potential use and misuse of rDNA technologies, as well as the associated and unknown risks (described later in this chapter). In the original formulation of the RAC

membership, Frederickson proposed that one-third of members be nonscientists or so-called public members. These nonscientists, among whom were ethicists, theologians, and university presidents, were to offer a broader public perspective on the emerging technology. Over time, RAC membership and responsibilities have evolved in response to scientific developments and public concerns.

Early Activities of the RAC

Early actions by the RAC included defining certain conditions for the awarding of grants for rDNA research pending adoption of more comprehensive guidelines. One of these conditions was that every research institution create a “biohazard review committee” (later renamed an “institutional biosafety committee”) to review risks and certify the presence of adequate safety measures. The major initial task of the RAC was the drafting of guidelines for rDNA research as advised by the National Academy of Sciences committee. The RAC was guided in considerable measure by the conclusions from a second conference at Asilomar in February 1975 (Berg et al., 1975). Those conclusions provided a framework for

- identifying and categorizing types and risks of different types of experiments,

- defining protective strategies tailored to the expected risks presented by an experiment, and

- deciding what research should continue to be postponed pending more knowledge and better safeguards.

The guidelines, first published in 1976 (Recombinant DNA Research Guidelines, 1976) and amended through the years, have provided a comprehensive description of facilities and practices to prevent unintended release of or human exposure to genetically modified organisms and material. They define the procedures for the RAC and outline requirements for research institutions’ oversight of rDNA research, including the creation of IBCs. Although some officials within what was then the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare argued that the guidelines should be issued as formal regulations, in the end they were not. NIH also established what is now the Office of Biotechnology Activities (OBA) to facilitate the operation of the RAC, the

implementation of the guidelines, and the coordination of rDNA-related activities at NIH (Rainsbury, 2000). Today, OBA describes its role as promoting “science, safety, and ethics in biotechnology through advancement of knowledge, enhancement of public understanding, and development of sound public policies” (OBA, 2013).

The guidelines are now formally known as the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (but are commonly referred to within the field as simply the “NIH Guidelines”) (NIH, 2013c) and remain a key vehicle for NIH oversight of rDNA research. The guidelines are applicable to all rDNA research that is conducted by or sponsored by a public or private institution that receives NIH funding for any such research (NIH, 2013a). In addition, many other U.S. government agencies and private institutions require that their funded research be conducted in accordance with the NIH Guidelines (Corrigan-Curay, 2013).

Changes in the Role of the RAC

Initially, the RAC reviewed and approved all gene transfer research protocols included in proposed research at institutions receiving NIH funds for rDNA research, advising the NIH director in issuing official approvals (technically, official approvals came from the director of NIH, based on the RAC’s decision (Freidmann, 2001). As discussed below, there have been several attempts to reshape the RAC’s scope and oversight, including legislative proposals by members of Congress, a report by the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical Research and Behavioral Research, Splicing Life (President’s Commission, 1982), evaluation by the congressional Office of Technology Assessment (OTA, 1984), and an ad hoc committee appointed by the NIH director (Verma, 1995).

As rDNA technology developed and understanding of its risks accumulated, the role of the RAC has evolved in a number of ways, as have the rDNA guidelines. In the 1990s, after a brush with termination, the RAC shifted into an advisory capacity and initiated the first of many revisions to the NIH Guidelines to ease constraints on rDNA research, including the implementation of an accelerated review process in 1993 (Rainsbury, 2000).

During the 1970s, however, as scientists were convening to establish the RAC, public interest and concern, even alarm, about rDNA research

grew (see, for example, Rainsbury [2000]). Both the Senate and the House of Representative held hearings in the 1970s and early 1980s. Members of Congress proposed various pieces of legislation that would have replaced the guidelines with regulations, extended the NIH Guidelines to include privately funded research, and created a national commission that would have diminished the role of NIH and scientific experts in overseeing rDNA investigations. Ultimately, no legislation along these lines emerged.

The controversy surrounding rDNA research was not eased in 1980 by the discovery that an U.S. investigator had conducted the first gene transfer experiment (which was not successful) in Italy and Israel in order to avoid RAC oversight (discussed in Chapter 2). The investigator was later censured (for misleading foreign regulators) and barred from NIH funding (Rainsbury, 2000).

Parties outside Congress also called for modifications in the public oversight of rDNA research. For example, in 1982, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical Research and Behavioral Research submitted to President Reagan and Congress a report titled Splicing Life (President’s Commission, 1982). The report reviewed public concerns and moral issues in genetic engineering and made recommendations for greater oversight related to ethical issues in gene therapy. Overall, however, the panel found that although some “have suggested that developing the capability to splice human genes opens a Pandora’s box, releasing mischief and harm far greater than the benefits for biomedical science, [t]he Commission has not found this to be the case” (President’s Commission, 1982). Two years later, the congressional Office of Technology Assessment concluded that existing oversight procedures were adequate for cell therapy that does not create changes that can be inherited (OTA, 1984).

One response at NIH to the Splicing Life report was the creation in 1984 of what became the Human Gene Therapy Subcommittee (RAC, 1990). The next year, the subcommittee, which was chaired by an ethicist, Leroy Walters, drafted guidance (“Points to Consider”) for the preparation and review of protocols for human gene transfer studies (somatic cell research only) (Points to consider, 1985). The guidance, which was revised after public comment and later integrated into the NIH Guidelines, identified more than 100 questions that covered both scientific and ethical aspects of protocols. This oversight framework was in place well before the first protocols for human trials were submitted.

The first protocol approved by the RAC (in 1988) involved a gene marker study. The approval was delayed by investigators’ reluctance to produce requested data on the safety of the procedure for fear of compromising their publication prospects (Rainsbury, 2000). The second approved protocol (1989) involved a test of gene transfer for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) (Wolf et al., 2009).

Initially, the RAC (through a subcommittee) reviewed all gene transfer research protocols. As the amount of research accelerated in the early 1990s, however, and a large number of similar protocols came under review, the review process became strained, which, in turn, increased criticism of the process. This strain occurred in the context of multiple other phases of protocol review, including reviews by IRBs, IBCs, and FDA. (For research involving investigators at different institutions, several IRBs and IBCs could be involved.) Among other responses (including attempts to expedite the review process), NIH and FDA agreed in 1995 that NIH would limit its public reviews to novel protocols, while FDA would assume primary responsibility for reviewing gene therapy protocols (Rainsbury, 2000; Wolf et al., 2009).

FDA first asserted a role in the oversight of gene therapy products—and therefore the research undertaken to develop such products—in 1984 (Wolf et al., 2009). The agency began to assert a greater role in regulation of gene therapy products in 1986 (Statement of policy for regulating biotechnology products, 1986), and in 1995, NIH and FDA agreed that primary regulatory responsibility for review of gene therapy protocols would rest with FDA (Rainsbury, 2000; Wolf et al., 2009). As a result, the RAC became an advisory body. FDA issued its own document, “Points to Consider in Human Somatic Cell Therapy and Gene Therapy,” in 1991 and issued guidance for industry on gene therapy in 1998 (FDA, 1991, 1998). FDA categorized these therapies as involving a type of biological drug1 and assigned oversight responsibility to what is now the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). By 1993, FDA had reviewed hundreds of clinical research proposals involving somatic cell and gene transfer technologies (Kessler et al., 1993).

At the behest of a RAC member in the early 1990s, the RAC began to review adverse event reports as part of semiannual reviews of NIH

______________________

1A synthetic oligonucleotide is regulated as a drug, not a biologic. See Intercenter Agreement Between the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, available at http://www.fda.gov/CombinationProducts/JurisdictionalInformation/ucm121179.htm (accessed November 1, 2013).

data management reports on gene transfer trials. Since 1997, tables of adverse event reports from gene transfer trials have been posted with the RAC meeting minutes. The summary descriptions vary significantly in the extent to which they include specific statements about the likelihood that a reported event can be linked to the gene transfer procedure.

In 1995, an ad hoc committee appointed by the director of NIH to advise on the future role of the RAC concluded that gene transfer research was different enough from other research to deserve continued public scrutiny. The committee concluded that the RAC should, however, no longer review every protocol; rather, its reviews should focus on protocols raising special concerns (e.g., those using novel vectors) (Verma, 1995).

In 1996, NIH published a notice in the Federal Register proposing to eliminate the RAC entirely (Notice of intent, 1996). The notice observed that NIH “has continuously relinquished oversight of various elements in the field of recombinant DNA research, as such elements reached maturity” (Notice of intent, 1996, p. 35775), and it proposed to transfer all responsibilities for approving gene transfer research to FDA. In the face of public resistance to this proposal, NIH did not eliminate the RAC, but it did end the RAC’s role in approving individual research protocols (Rainsbury, 2000; Wolf et al., 2009). Although the RAC thus became an advisory body, NIH still required and continues to require that NIH-supported investigators submit gene transfer protocols for advisory review. The RAC’s public reviews are selective, limited to protocols that present certain safety or ethical issues.

Concern about the conduct of gene transfer trials reached a new level of intensity after the death of Jesse Gelsinger in 1999. Subsequent investigations identified shortcomings in trial oversight and transparency related to reporting of serious adverse events in the trial, FDA’s sharing of information with NIH and the RAC, and investigator conflicts of interest. NIH’s response to the findings of the investigation included the creation of a working group to review NIH’s oversight of gene transfer trials (Advisory Committee to the Director, 2000). FDA and NIH also agreed on steps to coordinate adverse event reporting and expand public access to reports of serious events, for example, through the creation at NIH of the Genetic Modification Clinical Research Information System (GeMCRIS) (NIH, 2004), discussed further below. Congress again held hearings on rDNA oversight but did not act further (Rainsbury, 2000).

In 2000, NIH shifted the timing of the public reviews undertaken by the RAC so that they would occur before, rather than after, protocol re-

views by IRBs and IBCs. This would allow these entities to benefit more fully “from the expertise, broad perspective, and the experience of the RAC” (Recombinant DNA research, 2000, p. 60329). For example, the RAC could help IRBs and IBCs identify deficiencies in the informed-consent approach proposed by investigators.

Today, the RAC has responsibilities in addition to its advisory role in reviewing gene transfer protocols. As described in its updated charter, “as necessary, and with the approval of the Designated Federal Officer, the Committee and its subcommittees may call upon special consultants, assemble ad hoc working groups, and convene conferences, workshops and other activities” (NIH, 2011, p. 1). In recent years, OBA has sponsored or cosponsored meetings on gene transfer and rare diseases, vector and trial design challenges in studying retroviral and lentiviral vectors for long-term gene correction, challenges in trial design in research with gene-modified T cells, and future directions for gene therapy (NIH, 2011).

Current Role of the RAC

The RAC is currently administered and supported by OBA, located within the Office of the Director of NIH, as part of OBA’s responsibility to oversee federally funded rDNA research. The current charter of the RAC describes its role as providing “advice to the Director, NIH, on matters related to: (1) the conduct and oversight of rDNA, including the content and implementation of the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant DNA Molecules, as amended, and (2) other NIH activities pertinent to rDNA technology” (NIH, 2011, p. 1). The current guidelines also specify that research proposals involving the deliberate transfer of recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules, or DNA or RNA derived from such nucleic acid molecules, into human subjects (human gene transfer) are to be subject to a review process involving both NIH/OBA and the RAC (NIH, 2013c).

Within the entire gene transfer research oversight system, the RAC is the only oversight or regulatory body that provides a public venue for the review of a protocol. FDA, IRBs, and IBCs all convene in private; however, IRBs and IBCs often include nonscientists as members of their committees. Therefore, gene transfer protocols are one of very few areas of emerging human subjects research that receive additional oversight, and the only area for which that review occurs through an additional oversight body—even though, as previously discussed, its risk portfolio

is similar to other areas of emerging science. The public nature of the RAC is due to its status as a public advisory committee under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) of 1972. In order to comply with FACA regulations, the RAC must have open meetings with advance notice of the time and place, provide detailed transcripts, and allow public participation at meetings (Steinbrook, 2004). Thus, the RAC is an advisory body with oversight defined in NIH guidelines that require NIH-supported researchers and institutions to submit gene transfer protocols for advisory review. Human gene transfer trials conducted at or sponsored by institutions receiving NIH funding for rDNA research must be registered with OBA and reviewed by the RAC (NIH, 2013c). Completion of the RAC review process is compulsory based on adherence to NIH guidelines.

Currently, the RAC is “a panel of up to 21 national experts representing various fields of science, medicine, genetics, ethics, and patient perspectives that considers the current state of knowledge and technology regarding research with recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules” (NIH, 2013a, p. 2). A majority of the 21 voting members must have expertise in relevant scientific fields, such as molecular genetics, molecular biology, and rDNA research, including clinical gene transfer research. Further, at least four voting members must have expert knowledge in fields dealing with public health and safety, such as human subjects protection, environmental safety, ethics, and law. An FDA CBER representative is also an ex-officio member of the RAC. Terms for the chair and committee members, who are appointed by the director of NIH, are 4 years. The RAC meets in person quarterly in an open forum, with a webcast of the full meeting and the meeting transcript later posted online.

The RAC also may form ad hoc working groups, and currently it has several. For example, the Gene Transfer Safety Assessment Board consists of clinical members of the RAC who meet quarterly to review all serious adverse events that may possibly be trial-related as well as summaries of more than 400 amendments and annual reports filed on active protocols (Corrigan-Curay, 2013). The safety board reviews safety information from gene transfer trials for the purpose of assessing toxicity and safety data across trials and identifying significant trends or single events, and it reports such findings and aggregated trend data to the full RAC (Corrigan-Curay, 2013; NIH, 2013c). OBA considers this role as being akin to a “national Data Safety Monitoring Board,” responding in real time to emerging information (Corrigan-Curay, 2013).

The RAC also continues to sponsor public symposia on important scientific and policy questions related to rDNA research (Friedmann et al., 2001), providing a public forum for scientific experts to discuss emerging issues in the field of gene transfer. Along with the RAC’s protocol review and mechanisms to inform institutional oversight bodies, this transparent system is intended to optimize the conduct of individual research protocols and to advance gene transfer research generally (O’Reilly et al., 2012). In this way, the RAC serves as an important mechanism for scientific debate, informing institution-level oversight, increasing transparency, and promoting public trust and confidence in the field of gene transfer.

RAC Review of Individual Clinical Trial Protocols

Although the RAC no longer has formal approval authority, all human gene transfer protocols that are directly funded by NIH or conducted at institutions that receive NIH funding for rDNA research must submit responses to Appendix M of the NIH Guidelines for RAC review (see the following section for more information on Appendix M) (NIH, 2013a). One criticism of RAC oversight is that it does not apply to privately funded research. Private institutions, however, often voluntarily submit protocols and comply with NIH guidelines (Corrigan-Curay, 2013), in part because any NIH-funded institution involved in gene therapy clinical trials needs RAC approval. Consequently, there are very few gene transfer protocols that are not initially reviewed by the RAC (personal communication, Amy Patterson, OBA, August 21, 2013).

Public review of protocols is intended to achieve two purposes: (1) to disseminate information so that other scientists may incorporate new scientific findings and ethical considerations in their research, and (2) to enhance public awareness and build public trust in gene transfer research, allowing for a public voice in the review of the research (Scharschmidt and Lo, 2006). According to OBA, protocol review by the RAC serves many functions (Corrigan-Curay, 2013), including

- optimizing clinical trial design, increasing safety for research subjects, and, in some instances, strengthening biosafety protections necessary for researchers, health care workers, and close contacts of research subjects;

- improving the efficiency of gene therapy research by allowing scientists to build on a common foundation of new knowledge emanating from a timely, transparent analytic process; and

- informing the deliberations of FDA, the NIH Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP), IRBs, IBCs, and other oversight bodies, whose approval is necessary for gene therapy research projects to be undertaken.

Appendix M of the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules

Appendix M of the NIH Guidelines is a “Points to Consider” document that details the process and guidelines for information submission to the RAC for gene transfer protocols and describes the oversight employed by the RAC for clinical trials (NIH, 2013c). The guidelines stipulate that the RAC will not accept either clinical research protocols involving germ-line modification or procedures involving in utero gene transfer. This means, in practice, that NIH does not fund these lines of clinical research.

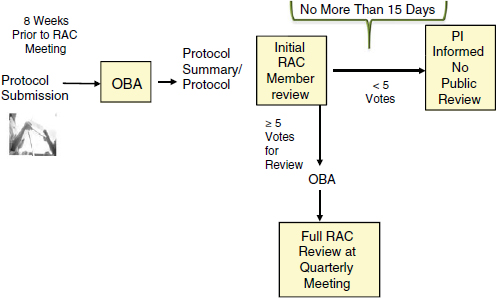

After an investigator submits a protocol, including responses to the points listed in Appendix M, OBA sends a summary to the RAC members for an initial review. During this preliminary review, the individual RAC members may request additional information or clarification or make specific comments or suggestions about the protocol design, the informed-consent document, or other matters. Any individual RAC comments of this nature are then conveyed to the investigator (NIH, 2013a). Based on the materials submitted by the investigator, including responses to Appendix M, only a subset of submitted protocols is selected for additional review by the RAC in its public forum (see Figure 3-1). Appendix M of the NIH Guidelines provides guidance to the RAC members about general characteristics that warrant public RAC review and discussion. Currently, the guidelines state that the RAC reviewers should

examine the scientific rationale, scientific content, whether the preliminary in vitro and in vivo safety data were obtained in appropriate models and are sufficient, and whether questions related to relevant social and ethical issues have been resolved. Other factors that may warrant public review and discussion of a human gene

transfer experiment by the RAC include: (1) a new vector/new gene delivery system; (2) a new clinical application; (3) a unique application of gene transfer; and/or (4) other issues considered to require further public discussion. (NIH, 2013c)

As an outcome of this initial review, each RAC member makes a recommendation as to whether the protocol raises important scientific, safety, medical, ethical, or social issues that warrant in-depth public discussion at the RAC’s quarterly public meetings (NIH, 2013a).

All comments by the RAC members are conveyed to the investigator (NIH, 2013a), and within 15 days of submission of the protocol, the investigator is notified as to whether the protocol has been selected for public review and discussion by the RAC. The in-depth, public review of a protocol may occur when either (1) the OBA director initiates a review following recommendations from at least three RAC members (current practice is at least five votes) (personal communication, J. Corrigan-Curay, OBA, September 1, 2013), or a federal agency other than NIH; or (2)

FIGURE 3-1 Summary of the human gene transfer protocol review process.

NOTE: PI = principal investigator.

SOURCE: Corrigan-Curay, 2013.

the NIH director initiates a review. All correspondence with the investigator is part of the public record for the protocol in question and is available to the investigator, sponsor(s), IRB(s), IBC(s), FDA, and OHRP (NIH, 2013a).

Prior to a scheduled public review, RAC members (and sometimes ad hoc members chosen for their expertise in the field) pose a series of questions in writing to the investigator about the gene transfer protocol. The investigator’s written responses are required to be submitted to the RAC prior to public meeting. At the meeting, the investigator responsible for the design and conduct of the trial makes a 15- to 20-minute presentation about the gene transfer protocol. The investigator will often bring colleagues to the meeting to help answer questions from the RAC members.

The current process is highly transparent. The OBA website posts protocols that are to undergo public review, and the protocols themselves are made available to members of the public upon request (OBA, 2013). Also, as mentioned previously, all correspondence between the RAC and investigators is also part of the public record for the protocol and is available to the investigators, sponsor(s), IRB(s), IBC(s), FDA, and OHRP (NIH, 2013a). However, according to OBA, in the past decade, there has been a decreasing emphasis on individual protocol review by the RAC; the percentage of protocols selected for public review dropped from 100 percent in 1992 to 37 percent in 2002 to 20 percent in 2012 (Corrigan-Curay, 2013).

Protocols Exempt from RAC Review

There are policy exemptions in place for certain types of human gene transfer protocols that are exempt from the RAC review. Appendix M Section VI-A of the NIH Guidelines details exemption for protocols for certain gene transfer vaccines against infectious diseases, specifically, those using plasmids and other vectors that usually do not persist (e.g., adenoviral vectors) and usually are administered intradermally or intramuscularly. The RAC does, however, review vaccine protocols that include a recombinant or synthetic construct that is not a microbial antigen, such as a gene to express a cytokine. It also reviews cancer vaccines for which the goal is not an immune response to a microbial antigen (NIH, 2013a).

Results of RAC Public Review

The RAC process of public review is defined as complete when, after the public review, the investigator receives a letter summarizing the RAC findings. A similar letter is then sent to the relevant IRB(s) and IBC(s) (NIH, 2013a). Minutes of the RAC meetings and webcasts of the meetings are made available on the public website. Neither investigators nor IRBs or IBCs are required to follow any of the RAC’s recommendations. Rather, a protocol’s approval comes from a collection of other regulatory bodies. A protocol must be approved by the relevant IBC(s) and IRB(s) before research participants can be enrolled in a clinical trial. These bodies often rely on the RAC recommendations in order to make their decisions, but the RAC’s approval per se is not required for the research to move forward (Wolf et al., 2009). FDA, the agency responsible for regulatory approval, considers the RAC recommendations as a basis for review decisions in its investigational new drug (IND) application process (described later in this chapter) (Takefman, 2013).

OTHER ENTITIES WITH REGULATORY OVERSIGHT OF GENE TRANSFER RESEARCH

In addition to the RAC oversight, gene transfer research faces several layers of federal and local oversight and regulations, which are required to initiate clinical gene transfer research protocols. This section briefly describes other entities with authority over gene transfer research and summarizes their interactions with the RAC, including each body’s legal establishment, roles and responsibilities, membership, and transparency, and notes any independent evaluation or assessment of impact of each body. This section also describes the relationship of each oversight body to the RAC and the timing of the work of each (in cases where this is dictated)—relationships that are important for assessing continuing need for the level and type of oversight currently provided by the RAC.

Food and Drug Administration IND Review

Although NIH provides funding for gene transfer research and has broad authority to oversee research involving rDNA and therefore gene

transfer research, the agency ultimately responsible for the regulation and approval of gene transfer technologies is FDA (which refers to these technologies as “gene therapy products”). An unapproved drug or, in this case, an unapproved gene therapy product, must undergo FDA review as an IND prior to human use.2 Gene therapy INDs3 are regulated by the Office of Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies (OCTGT) in FDA’s CBER. A key purpose of IND review is to ensure the safety and rights of subjects. The purpose of reviews of phase II and III clinical trials specifically is to help ensure that the quality of the scientific evaluation is adequate to permit determination of drug efficacy and safety. FDA receives approximately 40 to 60 gene transfer INDs each year. FDA’s review follows a regulatory framework in which FDA and the sponsor interact throughout the product’s life-cycle, from pre-IND to post-marketing surveillance. Since 1996, FDA has reviewed 840 gene transfer IND submissions, of which 370 are still active (Takefman, 2013). To date, none of the INDs has progressed to approval for marketing.

CBER regulates cellular transfer products, human gene therapy products, and certain devices related to cell and gene transfer. Within CBER, oversight of gene therapy research and products is the responsibility of the OCTGT. FDA defines gene therapy products as products that “mediat[e] their effects by transcription and/or translation of transferred genetic material and/or by integrating into the host genome … and [that] are administered as nucleic acids, viruses, or genetically engineered microorganisms” (FDA, 2006, p. 4). The general types of gene therapy products that FDA has reviewed to date are non-viral vectors (plasmids), replication-deficient viral vectors (e.g., adenovirus, adeno-associated virus), replication-competent oncolytic vectors (e.g., measles, reovirus), replication-deficient retro and lentiviral vectors, cytolytic herpes viral vectors, genetically modified microorganisms (e.g., Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli), and ex vivo genetically modified cells (FDA, 2013a). According to a statement by Jay Siegel to the U.S. Senate (U.S. Congress, 2000), CBER uses both the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 19384 and the Public Health Service Act of 19445 as enabling statutes for oversight. FDA regulates “all products that mediate […] ge-

______________________

2Investigational New Drug Application. 2013. 21 Code of Federal Regulations 312 § 1.

3A biological product is “any virus, therapeutic serum, toxin, antitoxin, or analogous product applicable to the prevention, treatment or cure of diseases or injuries of [humans]” (21 CFR 600.3[h]).

4Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. 1938. Public Law 75-717. June 25.

5Public Health Service Act. 1944. Public Law 78-410. July 1.

netic material by integration into the host genome, and that are administered as nucleic acids, viruses, or genetically engineered microorganisms” (FDA, 2006, p. 4). FDA also maintains a federal advisory committee, the Cellular, Tissue and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee, which reviews and evaluates available data related to the safety, effectiveness, and appropriate use of human cells, human tissues, gene transfer therapies, and xenotransplantation products that are intended for transplantation, implantation, infusion, and transfer in the prevention and treatment of a broad spectrum of human diseases and in the reconstruction, repair, or replacement of tissues for various conditions (Statement of policy for regulating biotechnology products, 1986).

The FDA approval process for new biologic drugs involves an investigator’s obtaining permission from the agency to commence human subjects research by filing an IND application. Unlike NIH’s regulations, which require the RAC review for all gene therapy protocols funded by NIH or intended to be carried out at institutions receiving NIH funding for rDNA research, the FDA process applies to all gene therapy research, regardless of source of funding. During FDA’s review of INDs and its subsequent review of major steps in the research process (e.g., movement from phase I to phase II studies), the RAC’s preliminary scientific and ethical review of human gene transfer, as well as its public discussion of novel applications, is taken into account (Takefman, 2013). Unlike RAC review, FDA’s review process and approval of INDs are closed to the public until a gene therapy product is licensed for marketing. Although several gene transfer products have progressed to late-stage trials, FDA has not yet approved any gene transfer product for marketing. When it does, the agency will post on its website key documents summarizing the findings of its assessments of the evidence submitted by sponsors.

FDA has a “Points to Consider” document that presents the current thinking of FDA/CBER staff about important issues in gene transfer (FDA, 1991). This document is intended to guide investigators in understanding FDA perspectives and requirements (development and testing) as they prepare their INDs. In 2013, FDA released an updated draft version available for public comment, “Considerations for the Design of Early-Phase Clinical Trials of Cellular and Gene Therapy Products” (FDA, 2013a).

Early Consultation: Pre-IND Meetings

To ensure that all regulatory requirements are met, FDA encourages an early “pre-IND” meeting between investigators and FDA officials

early in the protocol development process to discuss specific questions related to the planned clinical trial design. The meeting also provides an opportunity for the discussion of various scientific and regulatory aspects of the drug as they relate to safety and/or potential clinical hold6 issues, such as plans for studying the gene transfer product in pediatric populations (FDA, 2001). “Pre-IND” meetings are scheduled at least 4 weeks before a formal IND meeting with FDA officials and require investigators to submit information packages that describe the gene transfer product structure; proposed clinical indication; dosage and administration; preclinical and clinical study descriptions and data summary; chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) information; and objectives expected from the meeting (FDA, 2000).

For certain types of protocols—including those involving gene transfer products—it is sometimes necessary to discuss special issues regarding rDNA proteins from cell-line sources, for example, adequacy of characterization of cell banks, potential contamination of cell lines, removal or inactivation of adventitious agents, or potential antigenicity of the product (FDA, 2013a). An investigator is expected to consider and address FDA guidance from the “pre-IND” meeting, or an earlier informal “pre-pre-IND” meeting, for the gene therapy product before initiating the IND meeting with FDA review officials.

IND Process

As a general rule, when reviewing IND submissions, FDA balances potential benefits and risks to participants of gene therapy clinical trials (Au et al., 2012; Takefman and Bryan, 2012). Upon the investigator’s submission of the IND, FDA has 30 days to approve the IND or put it on clinical hold in order to obtain more data from the sponsor.

Content of an IND There are three main content areas covered by an IND: CMC, preclinical studies, and the clinical protocol.7 The CMC section of the IND includes details of product manufacturing, product safety and quality testing, product stability, and shelf life for all the components and procedures used in generating a gene therapy product. The CMC section also covers purity, identity, potency, and cell viability (for cell-

______________________

6A clinical hold is an order issued by FDA to the sponsor that delays a proposed clinical investigation or suspends an ongoing investigation.

7Investigational New Drug Application. 2013. 21 Code of Federal Regulations 312 § 1.

based products). FDA publishes detailed guidance about CMC requirements specifically for gene therapy products (FDA, 2008).

The preclinical studies section covers pharmacological and toxicological testing—both in vitro and in animals—necessary to judge whether the clinical protocol is of sound scientific rationale and reasonably safe and can thus proceed to human trials. Information is also required on absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Safety testing required specifically of gene therapy products includes (1) potential adverse immune responses to the ex vivo transduced cells, the vector, or the transgene; (2) vector and transgene toxicities, including distribution of the vector to germ cells in testicular and ovarian tissues; and (3) potential risks of the delivery procedure (FDA, 2012).

The clinical protocol section includes information about phase I, II, and/or III studies, including start dose, dose escalation, route of administration, dosing schedules, definition of patient population (detailed entry and exclusion criteria), and safety monitoring plans. It also includes information regarding study design, including description of clinical procedures, laboratory tests, or other measures to monitor the effects of the gene therapy product. Because vectors and transgenes of gene therapy products may persist for the lifetime of the research subject, FDA has issued guidance for observing subjects for delayed adverse events (FDA, 2006).

FDA Transparency

Federal regulations require that information about many clinical trials be posted at ClinicalTrials.gov, the government’s database for information about a large proportion of clinical trials, or a similar site, but, by virtue of statutory mandates, there is little to no transparency in FDA reviews during the IND stage, including whether the agency is considering an IND for a specific product. After FDA has approved a product, it may post the clinical, pharmacology, and other technical reviews on its website (see, for example, information for Ducord, an umbilical cord–derived stem cell product for use in certain transplantation procedures, as reported by Zhu and Rees [2012]). Although proprietary information is redacted from these posted reviews, the clinical reviews provide considerable information about the trials. They may summarize early-stage discussions about trial design and assessments of whether sponsors conformed to certain ethical and good trial practices standards. Also, as described in the following section, the GeMCRIS, a joint effort

of FDA and NIH, provides additional public information about gene therapy trials (Corrigan-Curay, 2013).

When necessary, FDA can engage its advisory committee (the Cellular, Tissue and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee) to receive public input about a pressing issue of broad applicability. FDA advisory committees can also review issues related to specific products; in fact, FDA clinical reviews of products have a specific section to summarize any advisory committee discussion.

Genetic Modification Clinical Research Information System

One area in which there is strong interplay between FDA and NIH is the GeMCRIS8 system. This database, which became operational in 2004, includes summary information on human gene transfer trials registered with NIH (NIH, 2004). GeMCRIS, a joint effort of NIH and FDA, is a comprehensive information resource and analytical tool for scientists, research participants, institutional oversight committees, research sponsors, federal officials, and others with an interest in human gene transfer research. Included in the GeMCRIS summaries is information about the medical conditions under study, institutions where trials are being conducted, investigators carrying out these trials, gene products being used, routes of gene product delivery, and summaries of study protocols. As of summer 2013, GeMCRIS provided information about more than 1,000 human gene transfer protocols, including type of vector and adverse events, and provided abstracts and links to materials from RAC reviews. In addition, the GeMCRIS system allows investigators and sponsors of human gene transfer trials to report adverse events using a secure electronic interface. As described earlier in this report, this feature was developed in response to the discovery that many investigators were submitting required adverse event reports to FDA but not to NIH.

Role of IRB Review

In addition to oversight by federal agencies, gene transfer protocols are reviewed at the institutional level by IRBs. The purpose of the IRB review is to protect the rights and welfare of research subjects in clinical

______________________

8GeMCRIS is accessible at http://www.gemcris.od.nih.gov/Contents/GC_HOME.asp (accessed September 1, 2013).

investigations. IRB review and approval is required for any research with human subjects supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)9 or regulated by FDA.10 IRB review is required for research conducted or supported by any of the federal agencies subscribing to the Common Rule, for research on products regulated by FDA, and for research conducted by investigators at any institution giving Federalwide Assurance (e.g., universities assuring the federal government that all of their research will conform to federal rules on human subjects research). The origins of IRB review date back almost 40 years to the Belmont Report (National Commission, 1978), which was issued by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in response to a mandate from Congress “to identify the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research.”11 The nationwide infrastructure for local review of research involving human subjects focuses on the protection of human participants in research and the consideration of ethical issues involved in such research. In recent years, the number of IRBs has dramatically increased, from 491 in 1995 to about 4,000 in 2008 (Catania et al., 2008).

For federally funded research, registration requirements and administrative oversight of IRBs is handled by OHRP within HHS. For research supporting applications for FDA approval of products, including privately funded research, FDA also has requirements for IRB review (FDA, 2013b). For gene transfer protocols, IRB approval can occur before or after RAC review (NIH, 2013a).

IRB Roles and Responsibilities

An IRB has the authority to approve, require modifications to (as a condition of approval), or deny approval to research and informed-consent documents. An IRB must also approve amendments to a study and review a progress report at least yearly. Further, an IRB has the authority to suspend or terminate any study for noncompliance. Federal regulations do not specify whether or not an IRB must hold open meet-

______________________

9Public Welfare: Protection of Human Subjects. 2009. 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46 § 101.

10Institutional Review Boards. 2013. 21 Code of Federal Regulations 56 § 101.

11National Research Service Award Act. (July 12, 1974). Public Law 93-348. July 12.

ings or make minutes and other IRB documents available to the public. These are matters for individual institutional policies or state law.

For any given research project, an IRB must have at least five members with varying backgrounds to perform an adequate review of the research protocol.12 An IRB must have sufficient expertise to be able to determine the acceptability of the proposed research in terms of institutional commitments and regulations, applicable law, and standards of professional conduct and practice. It must include at least one member whose primary expertise is in the relevant scientific area and at least one member whose primary concern is in a nonscientific area. It must have at least one lay member who is not otherwise affiliated with the institution and who is not part of the immediate family of a person who is affiliated with the institution. In addition, an IRB has the discretion to invite individuals with competence in special areas to assist in the review of complex issues, but those individuals may not vote. No IRB may consist entirely of members of one profession, and no IRB may have a member with a “conflicting interest”; however, regulations fail to define what a conflicting interest is.

Federal regulations12 require an IRB to determine that all of the following requirements are satisfied:

- Risks to research subjects are minimized.

- Risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to the subjects and the importance of the knowledge that may be expected to result.

- Selection of subjects is equitable.

- Informed consent will be sought from each prospective subject or the subject’s legally authorized representative.

- Informed consent will be appropriately documented.

- The research plan makes adequate provision for monitoring the data collected to ensure the safety of subjects, where appropriate.

- There are adequate provisions to protect the privacy of subjects and to maintain the confidentiality of data, where appropriate.

- Additional safeguards have been included in the study to protect the rights and welfare of vulnerable subjects, such as children, prisoners, pregnant women, and handicapped or disabled persons.

______________________

12Institutional Review Boards. 2013. 21 Code of Federal Regulations 56 § 101.

In order to evaluate a study’s informed consent documents and process, an IRB needs guidance as to the basic elements of informed consent. Those elements, listed in HHS regulations (known as the Common Rule),13 are as follows:

- a description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject;

- a description of any benefits to the subject or to others that may reasonably be expected from the research;

- the disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subject;

- a statement describing the extent, if any, to which confidentiality of records identifying the subject will be maintained;

- for research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation as to whether any compensation and/or medical treatments are available if injury occurs, and, if so, of what they consist and where further information may be obtained;

- an explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions about the research and research subjects’ rights and whom to contact in the event of a research-related injury to the subject; and

- a statement that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled, and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled.

The Common Rule states that the “IRB should not consider possible long-range effects of applying knowledge gained in the research (for example, the possible effects of the research on public policy) as among those research risks that fall within the purview of its responsibility.”13 A centralized IRB is one that conducts reviews on behalf of all study sites that agree to participate in a centralized review process. For sites at institutions that have an IRB that would ordinarily review research conducted there, the central IRB should reach agreement with the institutions and their IRBs about how to apportion the review responsibilities

______________________

13Public Welfare: Protection of Human Subjects. 2009. 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46 § 101.

between local IRBs and the central IRB.14 Arrangements have been proposed in which a central IRB conducts an in-depth review of multisite clinical trials and makes detailed reviews, minutes, and correspondence with investigators available to local IRBs, which can then choose to accept the centralized review rather than perform a full local review (Lo and Grady 2009). For example, the centralized IRB for the National Cancer Institute is designed to help reduce the administrative burden on local IRBs and investigators while maintaining a high level of protection for human research participants.

Independent Evaluation of IRB Impact

The IOM committee did not identify many evaluations of IRB performance in reviewing gene transfer protocols specifically. More generally, editorials and commentaries have criticized IRBs as slow, unnecessarily burdensome, inconsistent, and lacking expertise needed for reviewing clinical research (Emanuel et al., 2004; Silberman and Kahn, 2011; Straight, 2009). Otherwise, there is relatively little empirical study of IRBs.

The Gelsinger case provides the most in-depth assessment of one IRB’s performance with gene transfer research (the University of Pennsylvania’s IRB) (Riley and Merrill, 2005). To better understand the circumstances surrounding Gelsinger’s death and what might be learned and improved, the RAC created a working group and had further discussions of the protocol and related issues in December 1999 and March 2000. Other groups—including FDA, the University of Pennsylvania, and OHRP—also investigated. Collectively, they identified a number of shortcomings in the trial and its administration. These shortcomings included investigator conflicts of interest, unapproved changes in the trial protocol, omissions in informed-consent documents and procedures, insufficient resources for the IRB, problems in trial record keeping and monitoring by the investigators, and deficient reporting of adverse events. Among subsequent regulatory responses to reporting deficiencies were a strengthening of requirements for prompt reporting of adverse events, review of reports by independent analysts, sharing with NIH of FDA adverse event data from gene transfer trials, creation of an improved reporting system for adverse events in gene transfer trials, and

______________________

14Institutional Review Boards. 2013. 21 Code of Federal Regulations 56 § 101.

more public access to safety data from trials (Finn, 2000; Raper et al., 2003; Steinbrook, 2008).

In a 2002 assessment of the RAC as an oversight model (and the oversight of clinical gene transfer research general), Nancy King noted a need for increased education for investigators and local oversight bodies. King points out that “IRBs that review a lot of gene transfer research have a relatively limited experience of gene transfer review in comparison with other fields, simply because the overall volume is small. Thus, what IRBs need to know about gene transfer presumably needs to be relearned periodically” (King, 2002, p. 384). A 2011 review attempting to define the actual burden of IRB review found that IRBs presented with identical protocols did not always make recommendations consistent with each other or even necessarily consistent with federal policy guidance (Silberman and Kahn, 2011).

Role of IBC Review

IBCs are mandated by the NIH Guidelines, Section IV-B-2, to undertake review of safety risks at the level of the investigators’ own institutions (e.g., universities and research centers) for all forms of research utilizing recombinant (or synthetic) DNA. Because an IBC is a type of local review developed specifically for rDNA research, it has been suggested that because they are “developed specifically to provide additional review of rDNA research—[IBCs] should be considered part of ‘extra,’ not basic, review’” (Wolf and Jones, 2011, p. 6). Furthermore, OBA—the entity that administers the RAC—has official authority over IBCs as directed by the NIH Guidelines.

An IBC is required to have no fewer than five members with experience and expertise in rDNA technology. Two of the five members cannot be affiliated with the institution and must represent the interests of the surrounding community regarding health and environmental protection. Depending on the types of research conducted at an institution, these two members may need specific types of expertise (e.g., plant experts if research on plant rDNA is being conducted). The institution must ensure that the IBC has adequate expertise and training, using ad hoc consultants as necessary (NIH, 2013b). The NIH Guidelines encourage institutions to open IBC meetings to the public when possible and when consistent with the protection of privacy and proprietary interests (NIH,

2013c). The guidelines also require institutions to make meeting minutes available to the public upon request.

At each research institution covered by the NIH Guidelines, an IBC is charged with assessing risks to the environment of rDNA research and ensuring that the research is conducted safely and in compliance with the NIH Guidelines. The specific roles and responsibilities of the IBC are to

- provide independent assessment of containment levels required by the NIH Guidelines;

- provide assessment of facilities, procedures, practices, and the training and expertise of personnel involved in the research;

- ensure that all aspects of Appendix M of the NIH Guidelines have been addressed by the principal investigator;

- ensure that no research subject is enrolled in a human gene transfer experiment until the RAC review process has been completed and IBC approval has been obtained;

- for human gene transfer protocols selected for public RAC review and discussion, consider the issues raised and recommendations made as a result of review and consider the principal investigator’s response to the RAC recommendations; and

- implement contingency plans for handling accidental spills and personnel contamination.

Under the NIH Guidelines, IBC approval of a gene transfer protocol is necessary regardless of whether the RAC elects to publicly review the protocol. Moreover, although IBCs were created “to provide local review and oversight of nearly all forms of research utilizing recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules” (NIH, 2013a, p. 3). OBA notes that many institutions—at their own discretion—have expanded the scope of IBC review to cover “a variety of experimentation that involves biological materials (e.g., infectious agents) and other potentially hazardous agents (e.g., carcinogens)” (NIH, 2013a, p. 3).

RAC RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER GENE TRANSFER REGULATION AND OVERSIGHT BODIES

An analysis of whether a line of research warrants special review depends on what is special about it in relation to what regulatory and oversight functions already exist. In the RAC’s capacity to review individual

clinical gene transfer protocols, it has functions that complement and partially overlap those of FDA and institutions’ IRBs and IBCs (Ertl, 2009). All four entities review the safety of gene transfer protocols (Ertl, 2009). However, they differ with regard to the extent to which they discuss broader social and ethical implications of these new technologies in their deliberations, have broad stakeholder representation, and allow public access and participation in their meetings and deliberations (Ertl, 2009).

RAC and FDA

At the time of the original chartering of the RAC in 1974, there was little overlap in the responsibilities of the RAC and FDA for gene therapy studies (Friedmann et al., 2001). Since FDA was given jurisdiction over human gene therapy products in 1986, however, there has been increasing interaction through dual agency review of human gene therapy trials. More recently, it has been suggested that the RAC has strong redundancy with CBER in terms of expertise; CBER has specialized experience and a regulatory mandate (Ertl, 2009). When the RAC was formed 40 years ago, experience in FDA was limited and it was reasonable to assume that FDA reviewers might not have the requisite knowledge base in rDNA technology. Currently, however, FDA has increased expertise, particularly with establishment of the CBER Office of Cellular, Tissue and Gene Therapies. FDA is staffed by professional reviewers whose expertise in the areas of cell and gene therapy, and whose knowledge of drug development, is broad and deep. FDA staff have authored a number of well-reasoned and well-annotated guidance documents that address critical aspects of drug development within the field of gene therapy (see, for example, FDA [1998, 2006, 2013a]).

There are a number of similarities in types of data required by FDA and the RAC, particularly surrounding gene transfer product characteristics, preparation, and safety (preclinical studies and adverse events), and proposed clinical procedures. As a general rule of thumb, FDA requires far more detail about preclinical studies (e.g., specification of acute, sub-acute, and chronic toxicity testing) than does the RAC, and it requires details of manufacturing and chemistry that are largely omitted in the NIH Guidelines.

Differences remain between the RAC’s and FDA’s approach to oversight of gene transfer research. FDA, as the sole federal regulatory agency for biomedical products in the United States, focuses on safety and efficacy when evaluating gene transfer products, from the first time they

are used in humans through their commercial distribution (Kessler et al., 1993) and over the lifetime of their use. FDA regulation includes many steps that, by statutory provision, are confidential due to the presence of proprietary information (Wolf et al., 2009). In contrast, the RAC reviews address broader scientific, social, and ethical issues raised by gene transfer research, and the RAC is permitted to address these broader questions in its review of individual protocols as well (NIH Guidelines, see Section IV-C-2-e). In addition to scrutinizing a clinical trial’s safety, the RAC assesses its scientific value (Ertl, 2009). Lastly, RAC review is conducted publicly by a number of experts who are not necessarily employed by the government (Wolf et al., 2009).

In an attempt to encourage communication between the agencies, the RAC charter calls for a member of FDA’s OCTGT to be one of the nonvoting federal representatives to the RAC (NIH, 2011). This FDA representative keeps the RAC apprised of relevant new regulatory developments, including FDA’s receipt of gene therapy protocol INDs for review. In 2001, NIH and FDA harmonized reporting of adverse events, an issue cited in the aftermath of Gelsinger’s tragic death. The same forms now must be submitted to both agencies, and the reporting must adhere to the same definitions of the various types of adverse events—such as life-threatening, serious, expected, and unexpected adverse events.15 Adverse events must also be communicated to the appropriate IRB[s] and IBC[s].) (Adverse events can be reported through GeMCRIS. FDA collaborated with the RAC and NIH on the development of GeMCRIS (discussed earlier in this chapter). Finally, upon FDA approval of an IND, the principal investigator must submit a written report to NIH that includes any modifications to the protocol as required by FDA (Beach, 1999).

RAC and IRBs

Unlike the RAC, the IRB review protocols are part of a formal approval process for conduct at the sponsoring institution. One benefit of the RAC process noted by OBA is that it informs discussions these other bodies will undertake in making certain determinations about the protocol (Corrigan-Curay, 2013). In addition, not only does the RAC have a larger membership than most IRBs (and IBCs as well) and offer more diverse expertise, it also is governed by even more stringent conflict-of-

______________________

15Investigational New Drug Application. 2013. 21 Code of Federal Regulations 312 § 1.

interest rules (Ertl, 2009). The RAC members who are associated with the institutions involved in the clinical trial in any fashion are not permitted to participate in the discussion of the protocol, nor are they allowed to cast a vote (Ertl, 2009). Lastly, although IRB members may have concerns about potential long-term social implications in protocol review, federal regulations strongly discourage IRBs from considering them in their review decisions (Fleischman et al., 2011).

To guide local IRBs, NIH issued additional guidance on informed consent in gene transfer trials specifically intended to help investigators, IRBs, and others understand and follow the NIH Guidelines and regulations on rDNA research (NIH, 2002). IRB review is independent of and can occur after or before approval by the RAC. If a protocol is selected for public review by the RAC, however, the resulting RAC recommendations are communicated to the IRB, as well as to the IBC, FDA, and investigators (NIH, 2013a).

RAC and IBCs

The study sponsor must complete the research protocol and responses to Appendix M of the NIH Guidelines, which are then reviewed by the local IBC and OBA—the entity that administers the RAC and has official authority over IBCs. Before final IBC approval of a gene transfer protocol, the protocol must be submitted to OBA. Although no stipulations are made regarding what to do with the RAC recommendations, final IBC approval can only be granted after the RAC review process is complete (NIH, 2013c), and the local IBC is ultimately accountable to OBA (Kresina, 2001, p. 314).

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH OVERSIGHT AND REGULATIONS

Given the international and multisite nature of clinical trials and the increasing drive for transparency across clinical trials, it is important to note that the NIH Guidelines apply only to research for which at least one of the sponsoring institutions has received NIH funding. According to one recent review of gene transfer trial information from regulatory and other sources, as of June 2012, more than 1,800 trials have been approved, initiated, or completed in 31 countries (Ginn et al., 2013). The review reported that 65.1 percent of the trials were based in the Americas

(compared to 64.2 percent in 2007), 28.3 percent in Europe (compared to 26.6 percent in 2007), and 3.4 percent in Asia (compared to 2.7 percent in 2007). (Recent data for a number of countries are less complete than earlier data because some countries have stopped specific tracking of gene transfer trials.) More than half of all trials (63.7 percent, or 1,174) are associated with U.S. investigators or institutions (Ginn et al., 2013). For products for which FDA approval is sought, FDA review applies regardless of trial site and funding source.

Internationally, the regulation of gene transfer research is based on national policies, most of which apply to clinical research more generally. Many countries have voluntarily adopted international guidelines for the conduct of clinical research, and some have adopted special policies for the review of gene transfer trials. In the European Union, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has the responsibility to evaluate and supervise human and veterinary medicines and thereby protect and promote public and animal health (EMA, 2013).

In 2007, EMA established the Committee for Advanced Therapies as the unit responsible for assessing the quality, safety, and efficacy of medicines made from genes and cells, medicines that are termed “advanced-therapy medicinal products.” This committee provides a centralized procedure for the assessment and approval of medicines for marketing in the European Union. This process is mandatory for biologics (including gene and cell therapy products) and a number of other product categories, including medicines for the treatment of HIV/AIDS and cancer (Cichutek, 2008).

EMA, however, does not have authority to review and approve protocols for clinical research, including gene transfer research (Pignatti, 2013). Rather, that authority resides with national regulatory agencies. Every European Union (EU) state has, however, adopted the EU Directive on Clinical Trials (Kong, 2004), which requires states to adopt a system for the review of clinical research consistent with internationally recognized standards for good clinical practice for the ethical and scientifically valid design, conduct, and reporting of trials (Kong, 2004). FDA, which participated in the international process for developing these standards, also recognizes these standards and publishes them as guidance documents (FDA, 2012).

ASSESSING GENE TRANSFER RESEARCH OVERSIGHT

Assessments of the RAC Review Process

Some claim that the current mandate of the RAC adds another layer of non-regulatory review to protocols, thereby increasing time and expense (Breakefield, 2012). However, others note that in most public reviews of individual protocols, the RAC has recommended ways to improve safety. Examples of recommended protocol changes include tightening exclusion criteria for study participants with increased risk of complications, making safety end points more specific, and increasing efforts to detect serious adverse events (Lo and Grady, 2009). One analysis of the RAC review examined 53 full public reviews of gene transfer clinical trial protocols performed by the RAC between December 2000 and June 2004 to determine what trial design concerns or suggestions the RAC members raised during written review or public discussion or in a formal letter to investigators post-review (Scharschmidt and Lo, 2006). The analysis found that the selection of subjects was the most-frequently-raised issue related to study design (particularly the need to exclude patients at greater risk for adverse events), followed by dose escalation scheme, the selection of safety end points/adverse events, the overall design analysis, and biologic activity measures. Because this assessment was looking only at protocols that had been publicly reviewed, not all protocols submitted to OBA in that time frame, it is likely that fewer issues of trial design would have been found among protocols exempted from full public review (Scharschmidt and Lo, 2006). Further, the seriousness of the concerns was not noted, nor was how many RAC members shared the concerns. There was no examination of clinical trials employing other technologies matched for stage of development to assess whether concerns regarding trial design were specific to gene transfer or would also be found with other innovative clinical interventions (Scharschmidt and Lo, 2006).

In another study, Kimmelman analyzed an example of a public RAC review, a gene transfer protocol for Parkinson’s disease, to describe the ethical issues in complex translational clinical trials (Kimmelman, 2012). Kimmelman noted that often absent from the conversation about the risks of gene therapy are the risks of delivering and administering the gene transfer product, which includes the surgical procedure itself and the needle tracks. Kimmelman noted, however, that the RAC review did, in

this case, focus on surgical procedures—recommending a procedure while the patient is awake, rather than general anesthesia (Kimmelman, 2012).

CONCLUSION

The RAC and the complex array of regulatory infrastructure surrounding it was developed in response to a new technology that, like many emergent technologies, presented a special challenge to the protection of human subjects and raised an array of complex social and ethical issues. At the outset, the RAC review of individual protocols and the opportunity for public discussion were deemed necessary to shepherd in the new medical intervention in a responsible manner. Furthermore, at the time of the formation of the RAC, other regulatory entities were not yet in place to properly oversee the safety and ethical consideration of gene transfer research.

The IOM committee concludes that the RAC has successfully provided oversight for a complex technology for almost 40 years, and its value has been immense in ensuring safe clinical protocols that benefited from input from diverse experts. During this time, it has served as the primary avenue for public awareness of the scientific and ethical dialogue about the pace and boundaries of gene transfer research. After 40 years of experience, it is time for modernization. Concerns surrounding gene transfer, discussed in Chapter 2, are applicable to all new and emerging technologies. The committee found that although gene transfer research continues to raise important scientific, social, and ethical questions, not all gene transfer research is unique, and the time has arrived to develop an oversight process that has matured along with the science.

REFERENCES

Advisory Committee to the Director. 2000. Enhancing the protection of human subjects in gene transfer research at the National Institutes of Health. July 12. http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/rac/acd_report_2000_07_12.pdf (accessed November 1, 2013).

Au, P., D. A. Hursh, A. Lim, M. C. Moos, S. S. Oh, B. S. Schneider, and C. M. Witten. 2012. FDA oversight of cell therapy clinical trials. Science Translational Medicine 4(149fs31):1–3.

Beach, J. E. 1999. The new RAC: Restructuring of the National Institutes of Health Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee. Food & Drug Law Journal 54:49.

Berg, P., and J. E. Mertz. 2010. Personal reflections on the origins and emergence of recombinant DNA technology. Genetics 184(1):9–17.

Berg, P., D. Baltimore, S. Brenner, R. O. Roblin, and M. F. Singer. 1975. Summary statement of the Asilomar conference on recombinant DNA molecules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 72(6):1981–1984. Breakefield, X. O. 2012. Refocus the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee. Nature Medicine 18(7):1007.

Catania, J. A., B. Lo, L. E. Wolf, M. M. Dolcini, L. M. Pollack, J. C. Barker, S. Wertlieb, and J. Henne. 2008. Survey of U.S. human research protection organizations: Workload and membership. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 3(4):57.

Cichutek, K. 2008. Gene and cell therapy in Germany and the EU. Journal fur Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit 3(Supplement 1):73–76.

Corrigan-Curay, J. 2013. NIH Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (RAC) and gene transfer research. Independent review and assessment of the activities of the NIH Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee—Meeting one. June 4. Washington, DC. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Research/ReviewNIHRAC/Presentations%20Meeting%201/Corrigan-Curay_RAC%20Presentation.ppt (accessed July 1, 2013).

EMA (European Medicines Agency). 2013. European Medicines Agency legal foundation. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/about_us/general/general_content_000127.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580029320 (accessed October 31, 2013).

Emanuel, E. J., A. Wood, A. Fleischman, A. Bowen, K. A. Getz, C. Grady, C. Levine, D. E. Hammerschmidt, R. Faden, and L. Eckenwiler. 2004. Oversight of human participants research: Identifying problems to evaluate reform proposals. Annals of Internal Medicine 141(4):282–291.

Ertl, H. C. 2009. The RAC: Double, double, toil, and trouble? Molecular Therapy 17(3):397–399.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 1991. Points to consider in human somatic cell therapy and gene therapy. Human Gene Therapy 2(3):251–256.

———. 1998. Guidance for human somatic cell therapy and gene therapy. Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/CellularandGeneTherapy/ucm081670.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2000. Guidance for industry: Formal meetings with sponsors and applicants for PDUFA products. Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm153222.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2001. IND meetings for human drugs and biologics: Chemistry, manufacturing, and controls information. Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm070568.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2006. Guidance for industry: Gene therapy clinical trials—observing subjects for delayed adverse events. Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/CellularandGeneTherapy/ucm078719.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2008. Guidance for FDA reviewers and sponsors: Content and review of chemistry, manufacturing, and control (CMC) information for human gene therapy investigational new drug applications (INDs). Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/CellularandGeneTherapy/ucm078694.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2012. Vaccine, blood, and biologics: Sopp 8101.1: Scheduling and conduct of regulatory review meetings with sponsors and applicants. Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ProceduresSOPPs/ucm079448.htm (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2013a. Guidance for industry: Considerations for the design of earlyphase clinical trials of cellular and gene therapy products. Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/biologicsbloodvaccines/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/cellularandgenetherapy/ucm359073.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2013b. Institutional review boards frequently asked questions—information sheet—guidance for institutional review boards and clinical investigators. Rockville, MD: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/regulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm126420.htm (accessed September 1, 2013).

Finn, R. 2000. Why were NIH adverse event reporting guidelines misunderstood? Journal of the National Cancer Institute 92(10):784–786.

Fleischman, A., C. Levine, L. Eckenwiler, C. Grady, D. E. Hammerschmidt, and J. Sugarman. 2011. Dealing with the long-term social implications of research. American Journal of Bioethics 11(5):5–9.

Friedmann, T., P. Noguchi, and C. Mickelson. 2001. The evolution of public review and oversight mechanisms in human gene transfer research: Joint roles of the FDA and NIH. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 12(3):304–307.

Ginn, S. L., I. E. Alexander, M. L. Edelstein, M. R. Abedi, and J. Wixon. 2013. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide to 2012—An update. Journal of Gene Medicine 15(2):65–77.

Kessler, D. A., J. P. Siegel, P. D. Noguchi, K. C. Zoon, K. L. Feiden, and J. Woodcock. 1993. Regulation of somatic-cell therapy and gene therapy by the Food and Drug Administration. New England Journal of Medicine 329(16):1169–1173.

Kimmelman, J. 2012. Ethics, ambiguity aversion, and the review of complex translational clinical trials. Bioethics 26(5):242–250.

King, N. M. 2002. RAC oversight of gene transfer research: A model worth extending? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 30(3):381–389.

Kong, W. M. 2004. The regulation of gene therapy research in competent adult patients, today and tomorrow: Implications of EU directive 2001/20/ec. Medical Law Review 12(2):164–180.

Kresina, T. F. 2001. Federal oversight of gene therapy research. In An introduction to molecular medicine and gene therapy, edited by T. F. Kresina. Wiley Online Library. Pp. 303–317.

Lo, B., and D. Grady. 2009. Strengthening institutional review board review of highly innovative interventions in clinical trials. Journal of the American Medical Association 302(24):2697–2698.

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (National Commission). 1978. Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2002. NIH guidance on informed consent for gene transfer research. Bethesda, MD: NIH. http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/rac/ic (accessed October 1, 2013).

———. 2004. NIH and FDA launch new human gene transfer research data system. Bethesda, MD: NIH. http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/mar2004/od-26.htm (accessed October 1, 2013).

———. 2011. Charter: Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee. Bethesda, MD: NIH. http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/RAC/Signed_RAC_Charter_2011.pdf (accessed October 1, 2013).

———. 2013a. Frequently asked questions about the NIH review process for human gene transfer trials. Bethesda, MD: NIH. http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/ibc/FAQs/NIH_Review_Process_HGT.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

———. 2013b. Frequently asked questions of interest to IBCs. Bethesda, MD: NIH. http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/ibc/FAQs/IBC_Frequently_Asked_Questions7.24.09.pdf (accessed October 1, 2013).

———. 2013c. NIH guidelines for research involving recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules. Bethesda, MD: NIH.

Notice of intent to propose amendments to the NIH Guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules. 1996. Federal Register. 61(131):35774–35777.

OBA (Office of Biotechnology Activities). 2013. Office of Biotechnology Activities welcome page. http://oba.od.nih.gov (accessed September 1, 2013).

O’Reilly, M., A. Shipp, E. Rosenthal, R. Jambou, T. Shih, M. Montgomery, L. Gargiulo, A. Patterson, and J. Corrigan-Curay. 2012. NIH oversight of human gene transfer research involving retroviral, lentiviral, and adeno-associated virus vectors and the role of the NIH Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee. In Methods in enzymology, Vol. 507, edited by F. Theodore. Bethesda, MD: Academic Press. Pp. 313–335.