The Current State of Digital Curation

As the principles and practice of digital curation have developed, it has gained some recognition as a distinct field and garnered the attention of organizations dedicated to its improvement. Shared standards and norms for digital curation are appearing within many different disciplines and sectors and are filtering into other disciplines. Improved practices for ensuring the quality and durability of digital data are being established. The field of digital curation has many inducements to advance further, yet also faces some barriers. The benefits of doing digital curation are increasingly evident, but so are the actual and, often hidden, costs. In this chapter, benefits refer to measurable outcomes, such as the value of persistent access to high-quality and usable digital information products, as well as less tangible benefits, such as more complete and accurate data for decision making. Costs include the hardware, software, storage, and especially human labor of digital curation, as well as the potential costs to individuals, organizations, and society at large of failing to perform essential curatorial activities.

2.1 Evolution and Continuing Development of the Field of Digital Curation

Although processes, institutions, and skill sets for preserving and disseminating digital information have been known and in place in some disciplines for several decades, identifying that assemblage of practices is essential to fully establish the field of digital curation. Thus the field has grown from practices hardly recognized as curation per se—for example, researchers making note of metadata when collecting data—to international consortia engaged in defining shared norms and standards for digital curation.

The earliest organized efforts to curate machine-readable data in the United States began more than 50 years ago, when a few universities and government-supported research institutions established specialized repositories, called data archives or data libraries, to preserve and distribute numeric machine-readable data. The first social science data archive in the United States, the Roper Public Opinion Research Center, was established at Williams College in 1947. The first World Data Centers were created in 1957-1958 as an outgrowth of the International Geophysical Year. In 1962, the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) was founded at the University of Michigan.

During the latter part of the twentieth century, government agencies, national and state archives, and scientific data centers developed further capacity to manage, disseminate, and preserve machine-readable data. Academic libraries, corporate technical information centers, publishers, and others began to share responsibility for long-term curation of published literature in electronic journals and commercial databases. In the early 1990s, research collaboration among federal agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF), Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and some public and private university libraries advanced information architecture, storage, and retrieval techniques. Libraries and cultural heritage institutions also launched large-scale efforts

to digitize their collections and make them accessible to the public through the Internet (Waters and Garrett, 1996; National Research Council, 2000). In this period, much work in metadata, interoperation, shared resources, and discoverability was initiated, forming the foundation of digital library practices.

Organizations devoted explicitly to recognizing and developing the field of digital curation followed. For example, in 2002, the United Kingdom established the Digital Curation Centre (DCC).1 In 2006, the International Journal of Digital Curation2 was launched. In 2010, the National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) was established in the United States as a consortium of organizations committed to long-term preservation of digital information with particular emphasis on staffing needs and capacity building.3 The United States also maintains a strong presence in international organizations with some complementary and growing interests in digital curation, such as the Research Data Alliance (RDA) and the Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA).

The field of digital curation has established a good foundation. Many of the building blocks originated not only in digital repositories and libraries, scientific data centers, and topical archives, but from within the communities of researchers and producers of data themselves. In particular, the digital library community performed much of the foundational work in metadata, interoperation, shared resources, and discoverability. Development of the field of digital curation continues.

An early champion of the development of digital curation as a field was Jim Gray (although commentary on the topic had begun a number of years earlier, e.g., for the Human Genome Database (Fasman et al., 1997)). Gray articulated a “fourth paradigm” of scientific inquiry (Gray et al., 2002, 2005) to take its place beside the experimental, theoretical, and computational paradigms. This fourth paradigm, also known as “e-science,” depends on data-driven methods—and thus on properly curated data. Particularly in “Online Scientific Data Curation, Publication, and Archiving,” Gray and his collaborators (2002) working on the architecture for the Sloan Digital Sky Survey addressed digital curation as professional curators would, that is, as the critical work of annotation, preservation, and expert description of datasets. In doing so, Gray also affirmed that those performing curation would do well to learn, and not reinvent, the relevant concepts and techniques from librarians as they develop close collaboration with experts who have domain-specific expertise (Gray et al., 2002).

Today, the field of digital curation is challenged to keep pace with rapid change in all aspects of digital information. It must accommodate the immense increase in quantity of digital information, the many uses and reuses of that information, changing technology, and a continuum of people handling digital information in an array of organizational settings across all sectors. The continued advancement of digital curation involves not only meeting these challenges, but also maturing as a field. This currently includes the development and dissemination of norms and standards that enable sharing of digital information, best practices for improving and maintaining the quality of digital information, and skills and management techniques to protect and preserve digital information.

_______________

2See http://www.ijdc.net.

2.2 Shared Norms and Standards

Any collection of digital information is apt to be utilized for a great variety of purposes by many different kinds of users in quite different settings. Any collection of digital information is also likely to be aggregated with other collections, and to be shared, accessed, analyzed, and stored using many different kinds of technology. All of this makes shared norms and standards in digital curation imperative. Such norms are emerging, though to different degrees in different contexts. This section reviews some recent efforts to establish norms and standards in digital curation, and then considers some of the current variation in adopting or establishing shared norms and standards for digital curation in government agencies, research communities, and business.

2.2.1 Efforts to Establish Standards for Digital Curation

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), an independent nongovernmental membership organization that develops voluntary international standards, published the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model (ISO 14721:2003) in 2003. The OAIS is a framework for the responsibilities, processes, and functions that any archiving organization needs in order to preserve information and provide long-term access. A set of auditing tools, the Trusted Repository Audit and Certification (TRAC), provides metrics for assessing conformance with the OAIS Reference Model. TRAC formed the basis for another ISO standard, the Trusted Digital Repository, which was adopted in 2012 (ISO 16363:2012). Although these standards do not prescribe a specific set of practices for digital curation, they do provide a common framework for identifying deficiencies in existing repositories and benchmarks against which to measure progress (e.g., Smith and Moore, 2007; Tarrant et al., 2009).

In addition to this international nongovernmental initiative, several national governments have either established some shared standards for digital curation or helped coordinate others’ efforts to do so. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) began in 2002 to provide guidance regarding standards and practices for digital curation and the skill sets and tools it requires. Over a decade later, through products such as the digital curation lifecycle model4 and supporting documentation (frequently asked questions, checklists, etc.), the resource list for curation,5 and the collection of training materials,6 the DCC remains a valuable resource and exemplar for the emerging digital curation profession.

The United States, by contrast, lacks a single national center or association for digital curation. Many separate organizations are working to develop standards and define best practices for digital curation. Sometimes these organizations coordinate their efforts; too frequently they operate with little awareness of each other. Organizations such as the American Library Association’s Association of College and Research Libraries’ Digital Curation Interest Group, the Online Computer Library Center (now known as OCLC), the Coalition for Networked Information, the Library of Congress, the NDSA, and the Digital Library Federation, to name a few, raise awareness of digital curation, promote best practices, and provide professional development. Although some standards that support digital curation7 have been adopted in the United States (e.g., ISO 19115-2 for geospatial metadata and Dublin Core for author, title, and

_______________

4See http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/curation-lifecycle-model.

5See http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources.

6See http://www.dcc.ac.uk/training.

7See http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/metadata-standards/list.

subject tracking,8) many standards have not been implemented—even down to basic time encoding (ISO 8601). The specific reasons vary, but usually include absence of software implementations, inadequate documentation, or lack of an experienced community of peers from whom to seek guidance regarding the application of standards (Greenberg, 2009; Mize and Habermann, 2010).

2.2.2 Digital Curation Standards in Government Agencies

The degree to which government agencies adopt and follow standards for digital curation varies greatly. As noted in Chapter 1, the federal, state, and local governments create a massive flow of administrative documents as well as a large volume of statistical data for policy research. Government-sponsored scientific agencies also collect huge quantities of digital information. The curation of all this digital information is far from uniform. The extent to which scientific agencies have developed or adopted standards and policies for digital curation varies among agencies and between programs within a single agency.

Some of the best examples in the federal government include the three National Data Centers of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Earth Resources Observation and Science Center of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NASA established a federated set of data centers in the 1990s that collect, curate, and preserve data. Other agencies, such as the Department of Transportation, are now starting to develop repositories for their information assets.

Across government agencies that collect digital information and that fund scientific research, there has been an effort to draw attention to digital curation. Many have adopted policies that indicate a concern with the practice of proper curation of digital information. For instance, the NIH adopted a policy in 2003 that required all sponsored projects with more than $500,000 in direct costs to provide data management plans for sharing their data or to state why data sharing is not possible.9 NSF similarly requires all grants submitted after January 18, 2011, to provide a data management plan. In February 2013, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued a memo to heads of executive branch departments and agencies that asked them to submit plans intended to increase access to the results of federally funded scientific research, where results were defined to include peer-reviewed publications and data (Holdren, 2013). The federal government has been pressing hard for agencies to present properly curated . data for analysis with the creation of data.gov in 2009. Other high-level government reports (e.g., National Science Board, 2005; Interagency Working Group on Digital Data, 2009; Blue Ribbon Task Force on Sustainable Digital Preservation and Access, 2010) and publications by experts (e.g., Lord and Macdonald, 2003; Swan and Brown, 2008; Auckland, 2012; Lyon, 2012) have explored and illuminated digital curation and its many issues.

2.2.3 Digital Curation Standards in the Sciences

A number of changes are occurring in how researchers in the sciences aggregate, use, and share data. The gathering of original data has long been a hallmark of scientific research. The tradition of creating or collecting new data, analyzing the data, publishing the results, and often then abandoning the raw data is being displaced. The process of inquiry instead often begins with the selection of existing data followed by the application of new analytical

_______________

9See http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/data_sharing_guidance.htm.

techniques, such as data integration, data mining, text mining, modeling, simulation, and visualization, to those data. It concludes with new discoveries that are documented not only in publications, but also in derived or integrated data products, new analytical tools, and contributions of new data to reference datasets.

This new pattern of data usage has many implications (Parsons and Fox 2013). It puts a much greater imperative on the standardization of digital curation practices, so as to facilitate sharing. One of the best examples of this is the field of biodiversity informatics, a relatively new field that is devoted to the management and analysis of data concerning organisms, species, and biological communities. Its principal data types are:

- Natural history specimens in museums, herbaria, and other repositories;

- Observations of organisms in nature;

- Taxonomic names attached to these specimens and observations;

- Geographic distributions of species based on specimens and observations; and

- Character traits of organisms and species, including but not limited to morphology, behavior, and genetics.

As shown in Table 2-1, different data repositories relevant to the field of biodiversity informatics have utilized very different data standards.

Faced with this plethora of data standards, Biodiversity Informatics Standards (formerly, the Taxonomic Database Working Group, or TDWG10) undertook to develop standards to bring these databases into alignment. TDWG began operating in 1985 as an informal group of botanists interested in developing the ability to exchange data on taxonomic names and specimen data among botanical gardens and herbaria. The effort was formalized in 1994 as an activity of the International Union of Biological Sciences. Since that time, TDWG has collaborated with a variety of other professional groups to develop a range of ontologies and standards. Participants in these activities have come from taxonomy, evolutionary biology, computer science, philosophy, library information schools, and other fields. Together they have created a new community of practice devoted to data curation in biodiversity-related research. Perhaps the most important and far-reaching outcome of TDWG is the Darwin Core, a body of standards for data related to biological species, specimens, samples, observations, and events.11

_______________

11A similar set of activities for genomic data began under the auspices of the Genomic Standards Consortium (GSC) in 2005. Representatives of TDWG and GSC are now engaged in an exploration of how the Darwin Core and genomic standards can be integrated. See http://www.gensc.org.

Table 2-1 Variety of Data Standards in Biodiversity Informatics

| Major Data Repositories | Data Standards | |

| DNA and genes | International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaborationa (GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ) | Gene Ontologyb Genomic Standards Consortiumc |

| Species | Global Biodiversity Information Facilityd | Darwin Core Standardse |

| Populations | Global Population Dynamics Databasef | Ecological Markup Languageg |

| Ecological communities | DataONEh | Ecological Markup Languagei |

| Coastal and marine environments | Digital Coastj | Coastal and Marine |

| Ecological Classification | ||

| Standardk | ||

| Habitats | European habitatsl | EUNIS Habitat |

| Classificationm | ||

| Geospatial landscape data | U.S. National Geospatial Programn; European Environment Agency data/mapso | Open Geospatial Consortiump |

bhttp://www.geneontology.org/.

chttp://gensc.org/gc_wiki/index.php/Main_Page.

fhttp://www3.imperial.ac.uk/cpb/databases/gpdd.

ihttp://knb.ecoinformatics.org/software/eml/.

jhttp://www.csc.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/data.

khttp://www.csc.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/publications/cmecs.

lhttp://eunis.eea.europa.eu/related-reports.jsp.

mhttp://eunis.eea.europa.eu/habitats.jsp.

ohttp://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps.

phttp://www.opengeospatial.org/standards/is.

Standardization of digital curation in biodiversity informatics has helped that field advance. The biodiversity network, VertNet,12 is prospering. The Biodiversity Data Journal began accepting submissions of datasets in 2012. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)13 is also well established and contributing to setting curatorial standards in the field of biodiversity informatics. GBIF is an intergovernmental organization created in 2001 after several years of planning conducted through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Megascience Forum (now the Global Science Forum). GBIF provides a portal through which distributed databases of species and museum specimen information can be searched with a single query. National and regional node programs engage hundreds of data providers and assist them in complying with the standards for data transfer that are now established within the field of biodiversity informatics.

_______________

Although standards for sharing data and curating digital information are well developed in biodiversity informatics, they certainly are not unique to that field. Standards relating to the sharing and curating of data have also, for example, redefined the ecological sciences (Hunt et al., 2009), enabled major advances in astronomy (Goodman and Wong, 2009), and transformed research in the proteomics (see Box 2-1).

Box 2-1

Sharing Data in Proteomics

Over the last two decades, the biomedical sector has created several highly curated reference databases for genes, proteins, and other organic patterns. These are now considered an essential part of the life sciences research infrastructure. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) is one such resource. A PDB case study (Curry et al., 2010) observes that “Making available molecular representation, their 3-D coordinates and experimental data requires massive levels of curation to ensure that data inconsistencies are identified and corrected. A central data repository and sister sites accepts data in multiple formats, such as the legacy PDB format, the macromolecular Crystallographic Information File introduced in 1996, and the current Protein Data Bank Markup Language, valid since 2005” (pp. 42-43). The WorldWide Protein Data Bank uses a global hierarchical governance approach to data curation workflow. Its staff review and annotate each submitted entry prior to robotic curation checks for plausibility as part of the data deposition, processing, and distribution. “Distributing the curation workload across their sister sites helps to manage the activity” (Curry et al., 2010, p. 43).

Digital curation standards and practices among academic researchers are of course heterogeneous and vary greatly across fields. Fields such as genomics and proteomics have well-established standards for metadata and annotation (e.g., the Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment and the Minimum Information About a Proteomics Experiment). Such fields also have mechanisms and incentives to reward researchers for producing, publishing, and sharing well-curated information, as well as specialists who support digital curation. Other fields, such as archaeology or psychology, are less advanced in building the standards, infrastructure, and knowledge bases necessary for digital curation in their domain. Even in fields where digital curation is less developed, expectations are changing about the availability and use of data. For example, more journals are requiring that data used as the basis of a published article be available for possible reanalysis by readers.

Another important shift in the sciences with implications for standards in digital curation is the increased relevance of access to digital information across disciplinary boundaries. Epidemiologists now track outbreaks of influenza using the very same data that marketers analyze to target consumers with advertising for flu remedies.14 Literary scholars, computational linguists, and computer scientists all collaborate on crafting algorithms to mine vast bodies of digitized text, generating insights into the evolution of natural languages and the emergence of new concepts in popular culture. Some endeavors, such as the geospatial industry, arise exactly out of the collaboration across disciplines and sectors (see Box 2-2). This unprecedented sharing across not only areas of specialty, but across scholarly

_______________

14For a good example of the limitations of data reuse without a deep understanding of highly curated data, see Lazer et al. (2014).

Box 2-2

The Geospatial Industry

According to Matteo Luccio in the Metacarta Blog, “The geospatial industry consists of individuals, private companies, nonprofit organizations, academic and research institutions, and government agencies that research, develop, manufacture, implement, and employ geospatial technology (also known as geomatics) and gather, store, integrate, manage, map, analyze, display, and distribute geographic information—i.e., information that is tied to a particular location on Earth”15 (Luccio, 2008).

The geospatial industry is using properly created digital information—from sources as dispersed as converted historic paper records and maps to remote sensing platforms registering the Earth’s surface—to address questions as diverse as the introduction of invasive species, the spread of infectious diseases, and biological responses to climate change.

disciplines and even between those disciplines and businesses, governments, and nonprofit organizations also requires the articulation of and commitment to shared standards.

One of the finest illustrations of the datasets and analytical work that become possible when standards allow researchers to transcend the boundaries of disciplines, data platforms, formats, technologies, institutions, and even time is the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set (ICOADS). ICOADS is one of the most complete and heterogeneous collections of surface marine data in existence.16 Begun in 1981, it has been built through a collaborative effort of U.S. and international scientific agencies. The immense curation effort involved in its construction included assembling 261 million individual marine reports from ships, buoys, and other platform types from 1662 to 2007, digitizing the earlier entries, standardizing and normalizing data, detecting and correcting errors, and performing quality control. The collection contains observations from many different observing systems that encompass the evolution of measurement technology over hundreds of years. ICOADS holds a wealth of data that can be used repeatedly for purposes and in ways simply unimaginable at the time of collection. Current uses include providing the base reference of ocean surface temperature, relative humidity, and sea level pressure for historical climate assessment and climate change modeling (Woodruff et. al., 2011). ICOADS has greatly leveraged both the short- and long-term value of the data to stakeholders across the research community and the public. It is also a testament to the maturation of the field of digital curation.

2.2.4 Digital Curation Standards in the Business Sector

In the business sector, as in the sciences, major changes in the use of digital information have led to greater appreciation and advancement of the field of digital curation. Increased reliance on and exploitation of digital information in businesses is a common and well-recognized phenomenon. Corporations utilize digital information to devise business strategies, inform decision making, manage inventories and production, and extend marketing. In the commercial sector, targeted online advertising and retail sales are driven by ever-richer data on consumer interests and behavior extracted from databases of “clicks” or selections. Entire new industries have also developed around producing and distributing

_______________

value-added information products. These include weather forecasts based on data from the National Weather Service17 that are enhanced with special local or historical features; travel sites that aggregate air fares, hotel prices, local maps, and other destination information for travel planning and price comparison; or recommender systems that collect customer reviews for restaurants, stores, and services. Genealogical companies have acquired comprehensive census information on everyone in the United States born between 1790 and 1940 and everyone born in Britain between 1851 and 1911, have added billions of digitized records of births, deaths, and marriages, and have incorporated records on immigration and naturalization to create massive genealogical databases that subscribers can search.

In such a context, it has become understood that “digital curation is not just for curators,” but rather, that it is a core business function. As in the sciences, clear norms and standards in digital curation can facilitate the work. As data become a commodity that is traded and sold, explicit standards and policies regarding security, access, privacy, intellectual property, and reuse of data have become essential elements of data stewardship, as evidenced in the July 2012 symposium organized by the study committee.18 Professional standards for the design and operation of trusted repositories for digital information (ISO 14721:2003) require a governance structure, business and succession plans, designation of responsibility for data management and preservation, preservation policies, and mechanisms (Smith and Moore, 2007) to monitor and respond to changes in the technological, organizational, and financial environments (see the TRAC Audit and certification checklist19). Industry best practices also include the consideration of digital curation in acquisition plans for major systems or system upgrades and in decisions to contract with third-party service providers for storage and other services. Long-term data preservation methodologies are being integrated at executive levels across the entire enterprise (Rappa, 2012), and there has been growth in new positions such as chief data officer (Raskino, 2013).

Within the business sector, the motion picture industry may be exemplary for according explicit attention to digital curation—perhaps because its entire product line is now created, distributed, and stored in digital form. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ 2007 report, The Digital Dilemma, addressed archiving and accessing digital motion pictures from the perspective of the major motion picture studios. It highlighted two key findings:

- Every enterprise has similar problems and issues with digital data preservation.

- No enterprise yet has a long-term strategy or solution that does not require significant and ongoing capital investment and operational expense. (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 2007).

The report concluded that a cross-industry approach is required and that no single department or division could or should address digital curation challenges alone (see Box 2-3). Further, it suggested that collaboration must be fostered among stakeholders, especially to develop common strategies for digital preservation. The report also noted, “Archiving digital

_______________

17See http://www.weather.gov/.

18See http://sites.nationalacademies.org/PGA/brdi/PGA_070217.

19See http://www.crl.edu/content.asp?l1=13&l2=58&l3=162&l4=91.

Box 2-3

Seeking Standards for Digital Curation in the Motion Picture Industry

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ 2007 report, The Digital Dilemma, noted the need for collaboration in devising strategies and standards for digital curation. In particular: “The following questions raised by using digital technologies cannot be answered by any single department or division:

- What is the value of the content?

- Who determines the value of the content?

- What content will be archived?

- Who determines what content will be archived?

- How will the content be archived?

- Who determines how the content will be archived?” (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 2007)

data requires a more active management approach, and a more collaborative partnership among producers, archivists and users to exploit its full benefits.”

While the initial report was from the perspective of the major motion picture studios, a subsequent report, The Digital Dilemma 2 (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 2012), looked at all of the other producers of audiovisual content, such as nonprofits, independent filmmakers, documentarians who create far more content than the major studios (Maltz, 2012). Curation for audio and visual works in this category falls to university-based archives, independent nonprofit organizations, state archives, public libraries, museums, and independent private archives. These lack the funding, technical infrastructure, trained staff, and institutional support that the major studios have at their disposal for digital curation. Consequently, despite a desire for digitization, access, and preservation of material such as documentaries, oral histories, and interviews, only a small portion are being digitized and made accessible and an even smaller portion of born-digital recordings are captured, curated, and preserved. Nonetheless, the report noted an awareness of the significance of digital curation and of the importance of establishing policies and standards regarding digital curation, even among entities without the resources to implement them (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 2012).

2.3 Best Practices for Good Quality

As noted in Chapter 1, not all digital information is an asset. Enhancing information by cleaning data, detecting and correcting errors, and compiling comprehensive metadata can improve its quality and render it valuable. Good-quality digital information requires good-quality digital curation, and developing best practices to ensure good-quality data is another aspect of the maturation of the field of digital curation.

A recent NSF-funded workshop, “Curating for Quality: Ensuring Data Quality to Enable New Science” (Marchionini et al., 2012), yielded insights into the question of data quality and its relationship to digital curation. Quoting directly from the report’s Executive Summary:

- There are many perspectives on quality: quality assessment will depend on whether the agent making the assessment is a data curator, curation professional, or end user (including algorithms);

- Quality can be assessed based on technical, logical, semantic, or cultural criteria and issues; and

- Quality can be assessed at different granularities that include data item, data set, data collection, or disciplinary repository.

The workshop also identified several key challenges (Marchionini et al., 2012):

- Selection strategies—how to determine what is most valuable to preserve;

- How much and which context to include—how to ensure that data are interpretable and usable in the future, what metadata to include;

- Tools and techniques to support painless curation implementation and sharing, and technologies that apply across disciplines; and

- Cost and accountability models—how to balance selection, context decisions with cost constraints.

While the NSF-funded workshop addressed data quality from the perspective of the sciences, other efforts have been made to consider data quality in ways appropriate to the business sector. Curry et al. (2010) identified the following aspects of data quality as most relevant for digital curation to address in the context of business use:

- Discoverability and Accessibility—Users can find and access data in a straightforward manner.

- Completeness—All of the requisite information is available.

- Interpretation—The meaning of the data is unambiguous.

- Accuracy—The data correctly represent the underlying parameters.

- Consistency—The data do not contradict themselves, and values are uniform.

- Provenance and Reputation—The data can be reliably tracked back to their original source, and the source of the data is legitimate (Buneman et al. 2001).

- Timeliness—The data are up to date for the task at hand.

Preserving digital information has become an increasing concern of digital curation as digital information is repeatedly reaccessed to address new questions and as the technology for handling digital information continues to change. The ephemeral nature of digital data poses significant challenges in all sectors. The scientific enterprise needs long-term storage and preservation of digital information, not only so research findings can be confirmed, but so that new methods can be used to analyze existing data, new hypotheses can be tested, and entirely unanticipated questions might be answered.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory is cataloguing its primary collection of about 200,000 space mission tapes, wound on 12-inch reels and stored in airtight metal canisters. The tapes contain data relevant to long-term trends such as global climate change and tropical deforestation, but the tapes' greatest value, researchers say, may lie in the light they can shed on scientific questions that have not yet been posed. For example, NASA scientists ignored ozone data gathered on space flights in the 1970s because the readings were so low they thought they

were erroneous. In the 1980s, after British scientists suggested that a dangerous thinning of the ozone layer was under way, NASA scientists were able to confirm the observation from the old data. Without tomorrow's context, we do not know what is valuable today. Preservation of data, well beyond the original context and purpose of its collection, is a paramount responsibility of curation (Duerr et al. 2004).

Even when that responsibility is embraced, changing technology raises many hurdles to fulfilling it. The cultural heritage sector faces the challenge of preserving its holdings quite starkly. The records and artifacts of cultural, social, and political heritage are increasingly captured in a wide range of media and formats that are not necessarily built with long-term preservation in mind, are subject to rapid deterioration, and depend on software and storage technologies that often become quickly obsolete (ACLS, 2006). This may be a familiar problem for earlier nondigital formats, such as audio recordings (see Box 2-4), but it is not exclusive to those formats.

Box 2-4

The Loss of Cultural Heritage Through Deterioration of Records and Technological Change

Sound recordings are a striking example of cultural heritage data at high risk of loss. These include music, oral histories, and radio broadcasts preserved in a wide variety of formats and media. According to a 2004 survey, an estimated 46 million sound recordings were held by public institutions (such as libraries and archives) in the United States, but the exact number—and more crucially, the condition of these recordings—was not known (Heritage Health Index, 2004). In fact, respondents to the survey noted that roughly 44 percent of those reported sound recordings were currently in “unknown” condition.

The fragility of these data was confirmed in 2010 in a study by the National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress and the Council on Library Information and Resources (Bamberger and Brylawski, 2010). This study also concluded that many historical recordings already have been lost or cannot be accessed by the public. This lost data include many of the recordings of radio’s first decade, from 1925 to 1935.

Other endangered records of cultural heritage include the radio programs of the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS), established by the U.S. government during World War II to provide radio programs to U.S. personnel around the world. Most AFRS programing was distributed regularly on transcription discs and included an edited version of commercial radio broadcasts as well as original programming by the AFRS. The Library of Congress holds more than 100,000 of these discs, making it the second largest collection of radio programs in its collection, and the single largest resource for the study of radio broadcast programming between 1942 and the early twenty-first century. Today, however, the AFRS no longer produces transcription discs and exclusively uses satellite technology to distribute its broadcasts, making it difficult for the Library of Congress—or any other institution—to collect and preserve this important cultural content (Bamberger and Brylawski, 2010).

Cultural records are increasingly created digitally (ACLS, 2006) and initially hosted or stored on e-mail servers, websites, blogs, and social media sites such as Flickr, YouTube, and Facebook. While the common assumption is that digital formats are less vulnerable to loss than older storage formats such as magnetic tapes, wax cylinders, or vinyl records, this is not necessarily the case. The risks to digital formats may be different, but are still substantial. Indeed, a 2010 study by the National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress and the Council on Library Information and Resources (Bamberger and Brylawski, 2010) concluded that new digital audio recordings may actually be more fragile than those held in earlier formats and at risk of being lost even more quickly. This is because digital sound files can be easily corrupted, and widely used media, such as CD-ROM discs, may last only about 3 to 5 years before files start to degrade. To prevent the loss of cultural heritage and other cultural and research resources that result from changes in technology, digital curation attends to the persistence and durability of digital information, rather than the carriers or media on which they are stored. In the case of audio recordings, this involves audio experts actively monitoring, constantly maintaining, migrating, and frequently backing up the archives for which they are responsible.

2.5 Further Advancement in the Field of Digital Curation

The field of digital curation has evolved and matured. It now faces inducements to advance, yet also many impediments to further development. Some of these inducements and impediments are outlined here.

2.5.5 Inducements to the Advancement of Digital Curation

Among the surest inducements to improved digital curation are the scientific discoveries that have been made possible because of it, through the sophisticated use and reuse of properly curated digital information. Similarly, gains in the business sector that have been possible only through its myriad data-driven strategies and extensive digital assets provide a strong incentive to the further development of digital curation. A few other specific inducements to the advancement of digital curation as a field are reviewed here.

2.5.5.1 Inducement: Organizations

One impetus to the advancement of the field of digital curation is the existence of many organizations dedicated to the purpose of building the field, either generally or within a specific discipline. The DCC is an example of an organization whose efforts are to further the field of digital curation generally, while TDWG and GBIF, all discussed above, are facilitating the improvement of digital curation in their own disciplines. Numerous other organizations, universities, and data centers are developing guidance and training to help investigators manage their data effectively (e.g., DataONE, ICPSR,20 and the Federation of Earth Science Information Partners21). The existence of such organizations does not guarantee advancement of the field, however. Both the patrons of these programs and the programs themselves could benefit from assessing their offerings and committing to more coordination to reduce overlap as well as gaps.

_______________

20See http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/datamanagement/index.jsp.

21See http://wiki.esipfed.org/index.php/Data_Management_Workshop.

Nonetheless, these initiatives indicate a recognition of the value of advancing the field of digital curation and a willingness to devote organizational resources to that end.

2.5.5.2 Inducement: Government Requirements

Concern for digital curation is increasing across government agencies, resulting in requirements to perform digital curation as well as resources for the field. The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), for example, is actively encouraging and assisting federal agencies to transition from paper to electronic records. As federal agencies receive approval to convert to digital records, the flow of those records considered important enough for temporary or permanent storage by NARA is increasing rapidly. As a result, NARA has been adding new job titles to deal with digital records: digital imaging specialist, dynamic media preservation specialist, and information technology specialist.22

As noted earlier, a number of government funding agencies, including NSF23 and NIH,24 have also instituted requirements for data management plans as a condition for applying for research support from the federal government. The Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) is providing general terms and guidance for its grant applicants.25 The purpose of the data management plans is to ensure that research results and data collected and produced with public funds are available to the public, to encourage individual investigators to assume responsibility for managing their information assets, to promote good data management practices, and to facilitate data sharing and reuse—all of which should help to advance the field of digital curation.

At the time of this report, the committee was unable to identify any published formal assessment of the NIH data management plan requirement on improvements in data management. In the case of NSF and IMLS, data management plan requirements were put into place only in the past 2 to 3 years, so it is premature to measure their impact on data management. Nevertheless, the NSF plan appears to have fostered awareness of the importance of digital curation of data, as evidenced by numerous reports and plans26 and the emergence of tools to support the development of data management plans (e.g., DMPtool by the California Digital Library and DataONE).27

_______________

22See http://www.archives.gov/careers/jobs/positions.html (accessed 20 August, 2012).

23See http://www.nsf.gov/bfa/dias/policy/dmp.jsp.

24See http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/.

25See http://www.imls.gov/applicants/projects_that_develop_digital_content.aspx.

26See http://www.arl.org/focus-areas/e-research/data-access-management-and-sharing/nsf-data-sharingpolicy#.VRvPTxaNw5h.

2.5.5.3 Inducement: Protection of Assets

While the proper curation of digital information assets is of unquestioned value for the business sector, this extends beyond the digital information assets that businesses themselves control. At the BRDI Symposium on Digital Curation in the Era of Big Data: Career Opportunities and Educational Requirements, Steve Miller of IBM noted that, with the rise of social media, the general public is becoming the curator of many companies’ reputational assets, affecting their ongoing reputation and performance. As a result, companies find themselves struggling with curation issues for information that they do not own, but that is about them (e.g., Wikipedia,28 Yelp29) and may be factually incorrect or even fabricated (Miller, 2012).

2.5.5.4 Inducement: Professional Recognition

Explicit recognition of the work done by trained digital curators may also be an impetus to development of the field. That recognition comes in many forms. Citation practices are beginning to credit curators. Citation recommendations for the Federation of Earth Science Information Partners, for example, help “data stewards define and maintain precise, persistent citations for data they manage and provide fair credit for data creators or authors, data stewards, and other critical people in the data production and curation process.”30 Formal job titles for digital curators, whether in the research, government, or private sectors, are also bringing recognition to the field.

2.5.5.5 Inducement: Openness and Transparency

Another impetus to the continued development of digital curation as a field is a public concern for consistency and transparency in organizations of all types. In part, this concern is reflected in governments’ commitment to enable broad access to digital information to a wide range of researchers and to allow the private sector and individual citizens to benefit from research findings and data funded through tax revenues. This is viewed as an essential means to stimulate further scientific discovery and maximize return on publicly funded investments in research. For example, the Obama administration issued its Open Government Directive in December 2009, indicating that providing and maintaining data from all U.S. federal agencies in digital and accessible form is a central priority (Orszag, 2009). This commitment was underscored in February 2013 when the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy issued the aforementioned policy directive on public access to research information and data (Holdren, 2013). That directive instructed U.S. federal agencies to create plans for maximizing the accessibility of digital data and results from federally funded research, noting that increased accessibility facilitates productive reuse of data. The directive states that “policies that mobilize data for re-use through long-term preservation and broader public access” significantly enhance the impact of the federal investment in research. Greater access or reuse of these resources also “accelerates scientific breakthroughs and innovation, promotes entrepreneurship, and enhances economic growth and job creation.” The directive covers data and information resulting from research in all disciplines. Federal agencies that generate or fund a significant amount of cultural heritage data—including the Smithsonian Institution, the National Endowment for the

_______________

28See http://www.wikipedia.org.

30See http://wiki.esipfed.org/index.php/Interagency_Data_Stewardship/Citations/provider_guidelines.

Humanities, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services—are included in its scope.

Other research funders also now seek to ensure openness and transparency through digital curation policies that make the outputs of funded research, including data, readily accessible. Such policies are proliferating nationally and internationally, driven by the perceived potential that greater, long-term accessibility of data can increase the return on the initial investment in research (Houghton, 2011; Zuniga and Wunsch-Vincent, 2012, Beagrie and Houghton, 2014). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Principles and Guidelines illustrate this approach, noting: “Sharing and open access to publicly funded research data not only helps maximize the research potential of new digital technologies and networks, but provides greater returns from the public investment in research” (OECD, 2007). In recent years, research sponsors have recognized that communication of results is an essential, inextricable part of the research process and have explicitly earmarked funds to cover some of the costs of dissemination (e.g., the Wellcome Trust Open Access Policy31 was released in 2006 and strengthened in 2012 [Wellcome Trust, 2012]).

The value of consistent, transparent, and open practices of digital curation is not limited to the return on investments in research. Such practices may also assuage public concerns about privacy, confidentiality, and security. Several high-profile events, such as exposure of the National Security Agency’s PRISM program that captures metadata on private e-mail and telephone messages, security and data breaches at large commercial firms such as Target, and the electronic recordkeeping challenges associated with the Affordable Care Act, have all exacerbated this concern. Transparent practices and shared standards in the field of digital curation could help allay public concern.

2.6 Impediments to the Advancement of the Field of Digital Curation

Although the gains that will result from the continued development of the field of digital curation seem sufficient to compel that trajectory, nonetheless there are barriers to continued advancement. Some of the policies and practices discussed above regarding adherence to standards and sharing of digital information may not be universally welcomed. Researchers may be reluctant to share data for fear of being scooped or be unwilling to invest time and effort to curate their own data when the reward system recognizes publication of results more than publication or deposit of data (Hedstrom and Niu, 2008; Koch, 2009). Many disciplines have not developed a culture of data sharing (Borgman, 2010; Tenopir et al., 2011; Thessen and Patterson, 2011), and the forms of data that researchers are most willing to release are not necessarily fit for new applications (Cragin et al., 2010). In the private sector, data are often tightly held because they are a resource that provides a competitive advantage (Maltz, 2012; Miller, 2012). While public concerns might lead to more open data and transparency, misuse of digital information and real or perceived invasions of privacy could also result in a backlash against the use of digital information. Statutory requirements and social norms for confidentiality and privacy could thwart the prospect of using many types of personally identifiable information for research (Dwork, 2007). Best practices and effective techniques for balancing openness and privacy protection might enhance the value of digital curation as a field.

Beyond these potential barriers briefly sketched here, one other merits further discussion. That is the lack of financial resources. A lack of funding for digital curation will threaten not

_______________

31Position Statement in Support of Open and Unrestricted Access to Published Research, http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/About-us/Policy/Spotlight-issues/Open-access/Policy/index.htm.

only the digital information that curatorial practices are meant to protect and preserve, but will also threaten the development of the field, for example, through an insufficiency of training programs to prepare a properly skilled workforce. Concerns over available resources—particularly monetary constraints—are fairly commonplace (Tenopir et al., 2011). Systematic investments in digital curation, including educating and training a workforce capable of tackling the complex challenges of the field, have been proposed to accelerate the transition to data-intensive science (Hey et al., 2009) and to a data-driven economy, although the nature of the latter is still poorly understood or measured (Mandel, 2012).

An example of acutely insufficient financial resources for digital curation is the National Biological Information Infrastructure (NBII; USGS, 2011). The NBII was begun in 1994 to establish a single, online source of biological resource data and information from vetted sources. In 2001, the NBII established regional and thematic nodes on the web, providing access to the information resources most important to their individual geographic or scientific niches. The NBII provided visible benefits to the biological resource community, enabling data owners to maintain critical assets that might not otherwise be made broadly available and providing a single, web-based source of data from numerous organizations to facilitate search. It also provided users with direct access to data resources deeply embedded in structured databases relevant to biology that might not be accessible via a nonspecialized search engine (USGS, 2011).

Despite its demonstrated value to the research community, the NBII (like many federally funded projects) suffered a series of deep budget cuts. Funding for NBII fell from a high of $7 million in fiscal year (FY) 2010 to $3.8 million in FY 2011, and to $0 in FY 2012, resulting in its mandated termination. As a result, the main NBII website (originally at http://wdc.nbii.gov/ma), along with all of its associated nodes, was taken offline in January 2012. The public face of these data was effectively lost. Behind the scenes, though, the USGS and the Socio-Economic Data Application Center32 staff at Columbia University have been working with partners to identify ways—to the extent possible—to try to fill the gap left by the loss of the NBII program and to further curate the data from the decades-long, multimillion-dollar investment by taxpayers, scientists, and the federal government for widespread use.

2.7 Measuring the Benefits of Digital Curation

The value of active management and enhancement of digital information assets for current and future use may be evident in the abstract, but further efforts to measure the benefits and costs of digital curation are also part of assessing the current state of the field. This section considers aspects of measuring the benefits of digital curation. The following section will address the measuring of costs.

Benefits from digital curation accrue in a variety of ways: through efficiency gains, reductions in operating costs, opportunities to create value by doing things in new ways, and opportunities to market new products or offer new services. Precisely how much value curation adds to digital information and for whom are impossible to measure in the absence of an explicit market for digital products with differential pricing for curated and uncurated data. A further impediment to measuring the benefit of digital curation activities is that these activities do not map neatly to specific job titles or occupations with known ranges for prevailing salaries or wages. Moreover, the workforce demands for people with digital curation knowledge and skills

_______________

and the nature of the tasks they will be expected to perform will be contingent on the level of investments that organizations make in automating digital curation processes. The benefits of digital curation thus include many unknowns that defy estimation. Nonetheless, a framework may be constructed, defining different dimensions along which benefits of digital curation can be identified, examined, and eventually measured.

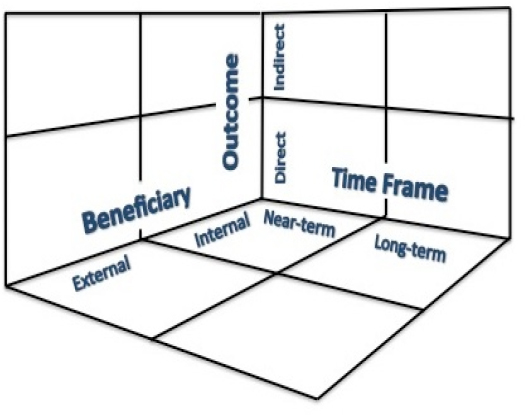

The work of Beagrie et al. (2010) provides one such framework. They propose a high-level taxonomy consisting of three dimensions (Outcome, Time Frame, and Beneficiary) along which the benefits of digital curation may be placed (see Figure 2-1). The outcomes of digital curation fall along a spectrum from direct through indirect. The time frame in which benefits are realized could range from near term to long term. The beneficiaries of digital curation could be internal to the curating entity or external, such as to a funding sponsor, another organization entirely, or some combination of them. Different metrics might be developed for measuring the types of outcome (direct and indirect), the time frame in which the benefit is realized, and the type of beneficiary (stakeholders internal to or affiliated with the organization undertaking the curation activity, and stakeholders external to or not affiliated with the organization undertaking the data curation activity). This is not an exhaustive list of dimensions; other dimensions could be added. The framework is a mnemonic to help ensure that no benefits are overlooked when assessing digital curation.

Figure 2-1 Framework for measuring the benefits of digital curation. Recast of the Beagrie et al. (2010) taxonomy into three dimensions (rather than sides on a triangle). In the process of assessing a digital curation project, benefits would be identified and located in each cell.

Fry et al. (2008) also address how to measure the benefits of curating and sharing research data. In their view, cost savings are the most direct and directly measurable benefit of digital curation. These savings can accrue to the depositor on the input side or the user on the

output side. Fry et al. (2008) also emphasize that cost savings can accrue to multiple participants in the research process. Research funders and research institutions may realize savings through increased efficiencies in collecting data, greater reuse of existing data, and elimination of redundant effort. Researchers themselves may benefit by their directing effort away from collecting, calibrating, and cleaning new data toward analysis of large pools of available digital resources and the development of new analytical techniques. If high-quality data were available for reuse, the burden placed on less obvious participants in the research process, such as the large numbers of human subjects required for experiments and the large number of respondents needed to produce valid samples for surveys, might be reduced. Authors, reviewers, editors, and publishers of research papers may also benefit from the ready availability of high-quality data to review and substantiate research findings.

Fry et al. (2008) identify other significant benefits in addition to direct cost savings that can accrue from digital curation. These include:

- Increased collaboration and cost sharing;

- Greater use of data in teaching and research training, especially in graduate and postgraduate education projects;

- New opportunities and uses for data, including data mining;

- Creation of a more complete and transparent record of research;

- Improved research evaluation and the direction of research; and

- Creation of new areas of research, new industries, or new support services.

Other benefits might be added to this list, including improved interdisciplinary research and greater opportunities for innovation as data sources not previously available are leveraged. Fry and colleagues have also begun to create a methodology for quantifying the financial value of the benefits of digital curation. That work is in its preliminary stages.

2.8 Measuring the Costs of Digital Curation

Measuring the costs of digital curation involves many variables and some assumptions, but efforts are being made to devise metrics. Guidelines are available to identify cost factors that should be included in any cost-benefit analysis. The guidelines provided by Beagrie et al. (2008) in the Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS) project permit the identification of a large percentage of the digital curation costs of a repository in a research environment. The KRDS model also provides a suite of useful tools, including a detailed description of cost variables and units, and an activity model—known as KRDS2—for identifying research data activities outside the repository, with cost implications for digital curation.

The KRDS model addresses costs in both the prearchive and archive phases of digital curation. The prearchive phase includes activities related to creating research data. In this phase, implications for repository costs are considered and strategies for data collection and creation are designed and implemented. The archive phase consists of the acquisition or disposal, ingestion, storage, and management of data, as well as access and user support. Administrative overhead, support services, common services, and estate costs must be included for both phases. The KRDS2 activity model provides a life-cycle costing method that identifies measurable component activities, variable cost drivers, and resources (e.g., staff time and equipment). It also provides a useful mechanism for understanding the costs of activities (Beagrie et al., 2010).

Using case studies from a variety of disciplines, Beagrie and colleagues (2010) observed the following cost trends associated with long-term curation:

- Acquisition and ingestion activities consistently cost the most.

- The costs of archival storage and preservation activities are consistently a small proportion of the overall costs and are significantly lower than the costs of acquisition, ingestion, or accession activities in all case studies.

- Potential cost-efficiencies can come from development of tools to support automation of ingestion and accession activities for curation and preservation.

- The costs of long-term data curation and preservation are dominated by fixed costs that vary little with the size of the collections.

- Staff members are the major cost component overall, and there is a minimum base level of staff coverage, skills, and equipment required for any service.

- Fixed-cost activities can reduce the per-unit cost of long-term preservation by leveraging economies of scale, using multi-institutional collaboration, and outsourcing as appropriate.

They further noted a trend of relatively high preservation costs in the early years of establishing a particular data collection. These are likely to be reduced substantially over time for longer-lived data collections (Beagrie et al., 2010).

For addressing the concerns of this report, that is, estimating demand for a digital curation workforce and providing sufficient and appropriate training for that workforce, it is highly significant that the KRDS2 model identifies staff costs as the major cost component overall. As the cost of digital storage decreases over time, activities that require human expertise and manual intervention will constitute an even greater portion of curation costs. It is also important to recognize that costs associated with staffing—including investment in the development of the right people, with the right expertise, at the right time—are interdependent and shifting.

Further, a number of strategies exist to reduce these staffing costs, including outsourcing, crowdsourcing, and the economies of scale achieved through collaboration across a community of researchers or among many research institutions. A key conclusion in the Beagrie et al. (2010) cost model is that leveraging such strategies could reduce the per-unit costs of digital curation. Other models helpful for analyzing the costs of digital curation include the Total Cost of Preservation model developed by the University of California Curation Center and the California Digital Library, as well as the Cost Model for Digital Preservation, the LIFE (Lifecycle Information for E-Literature) model, and the DataSpace model. These models focus primarily on the preservation aspect of digital curation. Recent work by Beagrie and Houghton (2014) integrates elements from a number of available cost models and demonstrates the value of synthesizing a range of quantitative approaches.

Two limitations of the existing cost models are worth noting. First, because the models estimate costs from the perspective of the repository, costs borne by the creators of digital information are not included in the model. When the creators of digital information have the foresight, resources, and ability to conform to digital curation standards and best practices, the costs to the repository for acquisition, ingestion, and quality control can be reduced. The extent of digital curation activity that occurs in this phase is easily underestimated. This is particularly so when the producers of digital information are performing the curation activities, such as

adding metadata, keeping track of versions of records, conducting quality assurance, and annotating entries. A strong dependency exists between the extent, quality, and timing of digital curation activities conducted by producers and the eventual costs of curation to a repository. If producers fail to provide contextual information about the content, structure, format, quality, and other aspects of their data, curators and other repository staff must spend time and effort to recover or add that contextual information (Niu and Hedstrom, 2007).

Second, although prearchive curation activities are highly desirable from the perspective of the repository because they accelerate the movement of digital information into preservation infrastructure and can lower costs to a repository, the benefits of prearchive curation activities to data producers are widely variable and not well articulated. Compelling examples of coordinated curation across the entire information life cycle that mutually benefit the producers, stewards, and consumers of digital information could serve as powerful models for the types of coordinated efforts envisioned in this report.

While proper digital curation imposes costs, inadequate digital curation can lead to many risks and even greater costs. Organizations of all types incur costs when they are unable to deliver the right information, in the right form, to the right players, at the right time. For some organizations, investments in digital curation are a form of risk mitigation. Commercial enterprises that collect revenue directly from sale or distribution of data and information products or services need effective digital curation for quality assurance and financial viability. Digital curation can help organizations that depend on access to accurate, timely, and authoritative digital information for business intelligence and decision making to reduce costly mistakes from the strategic level to operations.

The oil spill at British Petroleum’s (BP’s) Deepwater Horizon oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 provides an example of the risks of inadequate digital curation. Real-time data about the causes of the spill, its extent and impact, and the efficacy of efforts to cap the oil well were critical to addressing the situation and organizing a response that would limit damage to marine life, water quality, shoreline and beaches, and recreational activities in the Gulf of Mexico. BP, numerous federal agencies (the U.S. Coast Guard, NOAA, the Department of Energy, the USGS, and others), as well as state and local agencies provided data on the potential environmental and economic consequences of the spill. Disputes over the accuracy of the data provided by BP surfaced quickly and persisted throughout the containment and cleanup efforts. This not only hampered efforts to limit the disaster itself, but also resulted in damage to BP’s reputation and the assessment of fines and penalties on the company. Subsequent multibillion-dollar liability lawsuits against BP included one brought by the U.S. Department of Justice on behalf of multiple U.S. agencies that was settled in early 2012, with BP agreeing to fines of $4.5 billion (Krauss and Schwartz, 2012).

Inadequate investment in or performance of digital curation can also be costly in public policy. Insufficient and inefficient management of digital assets can become an issue in policy debates. Accurate and accessible information is critical to defining policy options, evaluating the potential effects of different options, and developing methods for implementing directives and statutes that have far-reaching immediate and long-term consequences for the public.

The importance of high-quality information for policy making was recognized during the health care reform process in the United States. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) worked to ensure that the policy makers considering sweeping changes to U.S. health care statutes were presented with accurate, up-to-date, and easily accessible data. Such data came from myriad sources and covered all aspects of the health care system, including insurance

coverage, care delivery, and outcomes. To meet these extremely broad needs, AHRQ convened a planning group to assess its data provision capabilities and to develop a strategy to optimize the availability of information and data for enactment and implementation of health care reform (AHRQ, 2009). The planning group recognized the need for a long-term effort to collect and analyze new data. It decided, however, that it was more efficient in the short term to focus on making current data more available, linking existing data resources, and in some cases identifying strategies to increase the timeliness of a subset of high-priority data. The planning group emphasized the immediate need for AHRQ to develop a “stand-ready” capacity to provide data that would optimize the effectiveness of the policy-making process, while also noting the ongoing need for data to track the impact of existing or new policies. This range of strategies was meant to mitigate the risks to health policy reform incurred as a result of poorly curated data.

Daunting as it is to estimate the actual costs of digital curation, estimating the costs of not doing digital curation is even harder. And costly as digital curation may be, the cost of failing to undertake these activities may be even greater. If irreplaceable digital information assets are lost, destroyed, or become inaccessible or uninterpretable through inadequate or improper curation practices, how can that loss be quantified? Unfortunately, such losses abound. In the cultural heritage sector, this includes many historic audio recordings and radio broadcasts, as discussed in Section 2.4. In the sciences, the wealth of information contained in the NBII, also discussed above, is at grave risk of being lost. Had not the Magellan Tapes (see Section 2.4) been properly curated, questions regarding ozone depletion could not have been fully addressed, even though such questions had not even been posed when the tapes were made. This would have been a costly loss. The potential for compounded costs due to the failure to conduct proper curation, and the difficulty of estimating those costs, are perhaps best illustrated by ICOADS, discussed in Section 2.2.3. Who, in 1662, conducting a cost-benefit analysis of the value of maintaining and storing ships’ logs, could have foreseen their use, once digitized, by researchers in the twenty-first century?

2.9 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusion 2.1: Demands for readily accessible, accurate, useful, and usable digital information from researchers, information-intensive industries, and consumers have exposed limitations, vulnerabilities, and missed opportunities for science, business, and government, as a result of the immaturity and ad hoc nature of digital curation. There is also a push for greater openness and transparency across many sectors of society. Taken together, these factors are creating an urgent need for policies, services, technologies, and expertise in digital curation. Although the benefits of digital curation are poorly understood and not well articulated, significant opportunities exist to embed digital curation deeply into an organization’s practices to reduce costs and increase benefits.

Conclusion 2.2: There are many inducements that could drive advances in the field of digital curation:

- Organizations that can serve as leaders, models, and sources of good curation practices;

- Government requirements for managing, sharing, and archiving information in digital form;

- Protection of digital assets to build trust and satisfy consumers and to maintain competitiveness in business and scientific research;

- Rewards and professional recognition for the value that curation adds to digital information; and

- Pressure from consumers, citizens, and society at large for accountability and transparency in business and government.

Conclusion 2.3: There are also barriers to developing the capacity for comprehensive, affordable, and effective digital curation. Some impediments, such as attitudes about sharing data and concerns over privacy, competitive advantage, security, and misuse of digital information, are difficult to delineate or measure. Insufficient financial resources for digital curation are a commonplace concern.

Conclusion 2.4: Cost models and studies of digital curation costs consistently identify human resources as the most costly component of digital curation. Current cost models are likely to underestimate the costs of curation tasks performed by the creators and producers of digital information, because no techniques have been developed to segregate or measure curation costs prior to accessioning into a repository. There is a pressing need to identify, segregate, and measure the costs of curation tasks that are embedded in scientific research and common business processes.

Conclusion 2.5: Although standards and good practices for digital curation are emerging, there is great variability in the extent to which standards and effective practices are being adopted within scientific disciplines, commercial enterprises, and government agencies. The absence of coordination across different sectors of the economy and different organizations has led to limited adoption of consistent standards for digital curation and resulted in the fragmented dissemination of good practices.

Recommendation 2.1: Organizations across multiple sectors of the economy should create inducements for and lower barriers to digital curation. The Office of Science and Technology Policy should lead policy development and prioritize strategic resource investments for digital curation. Leaders in information-intensive industries should advocate for the benefits of digital curation for product innovation, competitiveness, reputation management, and consumer satisfaction. Leaders of scientific organizations and professional societies should promote mechanisms for recognition and rewards for scientific and professional contributions to digital curation.

Recommendation 2.2: Research communities, government agencies, commercial firms, and educational institutions should work together to accelerate the development and adoption of digital curation standards and good practices. This includes (1) the development and promotion of standards for meaningful exchange of digital information across disciplinary and organizational boundaries and (2) interoperability between systems used to collect, accumulate, and analyze digital information and the repositories, data centers, cloud services, and other providers with long-term stewardship and dissemination responsibilities.

Recommendation 2.3: Researchers in economics, business analysis, process design, workflow, and curation should collaborate to identify, estimate or measure, and predict costs associated with digital curation. The National Science Foundation, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, relevant foundations, and industry groups should solicit proposals for and fund such research.

Recommendation 2.4: Scientific and professional organizations, advocacy groups, and private-sector entities should articulate, explain, and measure the benefits derived from digital curation, including “after-market” benefits, risk mitigation, and opportunities for private-sector investment, innovation, and development of curation technologies and services. The benefits should include outcomes that generate measurable value, as well as less tangible benefits such as the accessibility of digital information over time for scientific research, organizational learning, long-term trend analysis, policy impact analysis, and even personal entertainment. Such research is necessary for the development and testing of sophisticated cost-benefit (or cost-value) models and metrics that encompass the full range of digital curation activities in many types of organizations.

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Science and Technology Council. 2007. The Digital Dilemma: Strategic Issues in Archiving and Accessing Digital Motion Picture Materials. http://www.oscars.org/science-technology/council/projects/digitaldilemma/.

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Science and Technology Council. 2012. The Digital Dilemma 2: Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofit Audiovisual Archives. http://www.oscars.org/science-technology/sci-tech-projects/digital-dilemma-2.

ACLS (American Council of Learned Societies). 2006. Our Cultural Commonwealth—Report of the ACLS Commission on Cyberinfrastructure for Humanities and Social Sciences. http://www.acls.org/cyberinfrastructure/ourculturalcommonwealth.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2013.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2009. Filling the Information Needs for Healthcare Reform. Expert Meeting Summary and Identification of Next Steps. March 19. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/hinfosum.html. Accessed September 26, 2013.