Current and Future Demand for a Digital Curation Workforce

Digital curation is in demand and will be in demand across many sectors, from scientific research to business, health care, and cultural expression. Current demand is difficult to ascertain precisely, because of the dispersed nature of digital curation activities undertaken by many different actors in a broad range of organizational settings and institutional contexts. A lack of basic occupational data covering the field of digital curation also obstructs estimates. Nonetheless, estimates can be made of demand for both the current and future workforce in digital curation. This chapter explores trends in current and future demand and then considers some factors that may affect future demand, particularly automation.

3.1 Difficulties in Estimating Current Demand

Tracking current demand for the workforce in digital curation is difficult for three reasons. One is that the job is dispersed. As discussed in Chapter 1, digital curation is best conceived as a continuum, a set activities that may be accomplished by one or many people, whose professional identification and training may relate primarily to curation — or hardly at all. It may occur in a dedicated data repository, or in very different research, business, or cultural settings. How is a job to be counted, when it exists in so many permutations?

A second factor confounding estimates of the workforce in digital curation is that this is a fairly new field. The job title “digital curator” is only just emerging. Most federal agencies, for example, continue to describe their jobs dealing with the retention, organization, and dissemination of federal records as records managers, a job title that reflects the designation from an earlier time when records were kept as paper documents. Records manager remains an important federal government job title, even as the duties have expanded to deal with digital records. Identifying which jobs, though traditionally identified perhaps as records manager, data analyst, or librarian, have now evolved into de facto digital curator is a challenge.

The third obstacle to estimating current demand for the workforce in digital curation is, ironically, the lack of data. The primary source of statistics on employment is the federal government, principally the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). At this time, the BLS does not track digital curation as a separate occupation.

All three of these factors impede the estimation of current demand for the workforce in digital curation. All three need to be addressed. Regarding the first: conceiving of digital curation as a continuum of activities is an accurate way to capture how the field is actually practiced, but it may be taken to an extreme. When digital curation is defined as the active management and enhancement of the utility of digital

information assets for current and future use—then almost all activities associated with information can be said to be digital curation. A more reasonable account of the continuum of activities might place curation-related jobs in order, from those in which digital curation is the sole activity of a job’s incumbent, to those in which digital curation occurs from time-to-time in a job that is embedded in some other domain. Job data may be sifted with this understanding of the continuum in mind.

The second impediment to estimating the demand for digital curators, that is, the lack of a job with that title, is beginning to recede. For example, a recent opening for the job of data curator and analyst identified by Miller (2012) included the following duties:

- Develop and maintain tools/codes for day-to-day data extraction, curation, and management;

- Extract and provide clean data;

- Measure and track quality improvements in data;

- Increase awareness of value of the data quality;

- Work closely with IT groups and statistical teams; and

- Create and present summary statistics and reports

This job title is clearly for a digital curation occupation as the committee has defined it. Although the title of digital curator has not existed in the past, it is beginning to emerge. This will facilitate the tracking of demand.

The third obstacle to estimating demand—the lack of government statistics—merits further attention. The chief source of data on jobs in the United States is the BLS. Unfortunately, none of the jobs in the BLS Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) is titled “Digital Curation.” This may change as the SOC is revised.

To count the number of workers in an occupation, the BLS uses as its employment measure the number of jobs in a particular occupation, not the number of workers, and defines job growth as the sum of the new jobs created and the number of new hires of replacement workers needed due to turnover. The BLS gathers employment and wage data through its Occupational Employment Statistics (OES), a semiannual survey of approximately 200,000 firms from the 50 states and 4 territories. The BLS sample is selected from about 7 million firms. The self-employed are not included in the survey.

Under the OES program, new occupations are added as they emerge. The expansion of occupations that are listed in the SOC system and that are surveyed and analyzed reflects major changes in the U.S. labor force. The SOC was last updated in 2010, when 24 new detailed occupations and codes were added. Four of these were in computers and mathematical occupations, consisting of (1) information security analysts, (2) web developers, (3) computer network architects, and (4) computer network support specialists (BLS, 2012a).

The next revision of the SOC will be completed in 2018. The revision is likely to add further computer and mathematical occupations, but it is not clear at this point that digital curation and related occupations will be included. The process for developing a new SOC includes a solicitation for public recommendations of new SOC codes. A Federal Register (BLS, 2014) notice soliciting recommendations for new occupations was issued on May 22, 2014. The public was encouraged to respond to the notice and to

make recommendations and provide justifications for new occupations that should be added to the SOC. Digital curation responsibilities currently incorporated into other occupations could be separated in 2018 or in a later revision. Thereafter, revisions are planned to be made every 10 years (BLS 2012a).

3.2 Estimating Current Demand: Job Openings

While estimating current demand for a digital curation workforce is difficult, it is not impossible. Knowledge of how digital curation is conducted and how occupations are labeled can help in interpreting the job data that are available. Private-sector sources can supplement incomplete or inadequate government data. One very useful source of information is data on job openings.

The data used here come from job postings over the past 7 years, using historical data from the private company Indeed.com, a recruitment advertising network that aggregates job listings worldwide and across the private and public sectors. Indeed.com gathers listings of job openings from thousands of sites, including job boards, individual company career pages, newspaper classified sections, business and professional associations, and blogs. The company’s listings cover the private sector extensively, and also gather openings from federal, state, and local governments. Some details of the methods used by Indeed.com are available on the company’s website.1

Table 3-1 compares a number of traditional computer and mathematical occupations to job titles related to digital curation. As expected, some traditional computer and mathematical occupations have many more job openings than those in most job titles related to digital curation. Yet, despite their small absolute size, most job openings related to digital curation have been growing much more rapidly than the openings for computer and mathematical occupations.

All of the computer and mathematical occupations in Table 3-1 had more openings in 2012 than they did in 2005. The growth rate of these occupations was substantial, but none of the occupations grew by more than 120 percent during the 7-year period. Several of these individual occupations have a substantial share of the job openings compared to all occupations, with two occupations having more than 1 percent of economy-wide job openings—software developers (1.4 percent) and computer systems analysts (1.1 percent).

_______________

Table 3-1 Job Trends from Indeed.com. Job Openings in Computer and Mathematical Occupations and in Occupations Related to Digital Curation, 2005 to 2012.

| Occupation | Percent of Openings 2005 | Percent of Openings 2012 |

| Computer and mathematical occupations | ||

|

Software developers |

0.8 | 1.4 |

|

computer systems analysts |

0.8 | 1.1 |

|

computer support specialists |

0.1 | 0.3 |

|

network administrators |

0.1 | 0.2 |

|

computer programmers |

0.12 | 0.15 |

|

computer research scientists |

0.05 | 0.08 |

|

data base administrators |

0.01 | 0.03 |

|

Occupations Related to Digital Curation |

||

|

Enterprise architects |

0.3 | 0.8 |

|

data governance |

0.1 | 0.4 |

|

enterprise governance architects |

0.01 | 0.08 |

|

data stewards |

0.01 | 0.05 |

|

information curators |

0.001 | 0.01 |

|

Data Curators |

0.0 | 0.002 |

|

Librarians |

0.06 | 0.06 |

|

Archivists |

0.03 | 0.06 |

NOTE: Percentages are rounded.

SOURCE: Data from www.indeed.com/jobtrends. Accessed August 17, 2012.

By contrast, job openings related to digital curation have experienced much larger increases in percentage terms, with all but the librarian occupation at least doubling over the past 7 years. The librarian occupation experienced no growth, although tasks requiring digital curation expertise may nonetheless have increased within that occupation. Despite the rapid growth in job openings related to digital curation, most of these occupations have had few openings recently. Enterprise architect (0.8 percent) and data governance (0.4 percent) occupations, however, have had more job openings than four of the computer and mathematical occupations listed.

Data regarding job openings listed by Indeed.com also furnish the information presented in Figure 3-1. This figure illustrates the trend of an increase in job postings that seek digital curators from 2005 to 2012.

Figure 3-1 Job openings containing a “digital curator” job title, 2005 to 2012. Percentage of job openings found by Indeed.com that contain the term “digital curator.”

SOURCE: Indeed.com (2012).

Figure 3-2 Trends in posting for positions that used the term “information steward” in the job description.

SOURCE: Data extracted from Indeed. com (2012).

Similarly, Figure 3.2 uses data from Indeed.com to illustrate the increase in postings for positions that used the term “information steward” in the job description. The colored arrow represents the upward trend, determined by the low point, the high point, and an estimate of the mean.

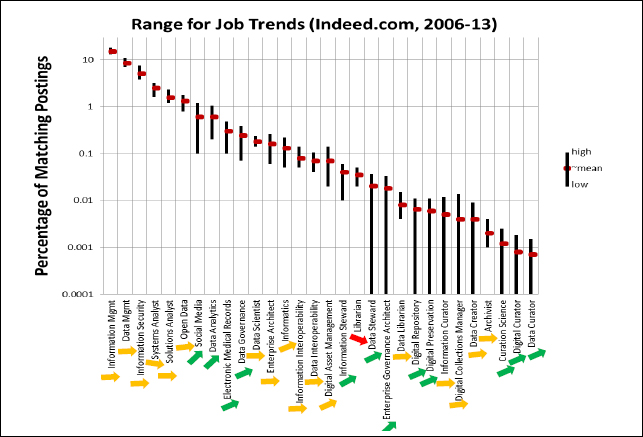

Figure 3-3 summarizes these parameters for a collection of 30 terms related to digital curation in one logarithmic chart. The arrow colors relate to the trend—green indicates a substantial upward trend, yellow a flat or more gradual change, and red indicates a significant downward trend.

One can observe from this figure that application areas such as social media, data analytics, and electronic medical records are experiencing substantial rates of growth, as are some of the core digital curation areas such as “data governance,” “data steward,” “digital repository,” and “digital preservation.” It is also worth noting that of these 30 terms, a third of them began to appear in position descriptions only after 2006.

Figure 3-3 Percentage range and trend of jobs that contain identified terms. Green indicates a substantial upward trend, yellow a flat or more gradual change, and red a significant downward trend.

SOURCE: Indeed.com (2012).

A new study by the Conference Board identifies librarians, archivists, and curators as occupations that are likely to experience labor shortages in the next 10 years (Levanon et al., 2014). That study used government data and estimates of retirements by baby boomers, projected demand for employment, current unemployment and labor participation rates, percentage of positions in an occupation filled by immigrants, and projected productivity increases in 266 industries and 464 occupations in the U.S. The report found that most occupations with a high risk of labor shortages are projected to

either experience high employment growth or have few new entrants to replace those who leave, but not both. For librarians, archivists, and curators the report projects an average employment growth of 8 percent over the decade, but an inadequate supply of new entrants to replace those who retire or leave the occupation (Levanon et al., 2014, p. 21). The study does not explicitly mention the implications of digital curation for the employment outlook for librarians, archivists, and curators, but it is worth noting that labor markets for occupations with knowledge and skills that are essential for digital curation, such as computer-related occupations, also are projected to be tight.

3.3 Estimating Current Demand: Placements

Other sources of information provide data helpful for estimating current demand for the workforce in digital curation. Students are now graduating from library and information science (LIS) schools, information schools (iSchools), and some management information systems programs in business schools with credentials in information management that fit the committee’s definition of digital curation. The ease with which these recent graduates are placed in jobs and the initial trajectories of their careers provide indirect indicators of current market demand. The trends revealed by these indirect indicators are consistent with the trends presented above using data on job openings.

Interpreting these indirect data requires attention to the current state of professional training. Because digital curation is an emerging field, relevant professional training may not be reflected in the formal titles of final degrees. Rather, it may be found in the various programs, subspecialties, and certificates associated with professional degrees in library science, information science, and even business.

Despite the lack of public access to comprehensive survey data, some trends in the experience of LIS graduates can be discerned.2 A 2011 survey of recent graduates of LIS programs in the United States, with respondents from 35 percent of alumni (N = 2,162) from 41 programs, support a possible trend in digital curation positions: “LIS programs and graduates alike reported an increase in the number of emerging job titles, including … digital curator.” Graduates also reported new responsibilities in digitization, data collection, and analytics (Maatta, 2012).

A survey of 2010 graduates in LIS by Library Journal showed that 78 percent were employed (Maatta, 2011). The titles for the digital curation–related positions accepted by graduates included:

- Data management specialist,

- Data management librarian,

- Data curator,

- Data librarian,

- Data services specialist,

- Data research scientist,

- Data curation specialist,

- E-science librarian,

_______________

2The Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE) compiles information on LIS graduates and their placement, but these data are available only to ALISE member organizations.

- E-research librarian,

- Science data librarian, and

- Research data librarian.

However, of the 1,346 respondents to this survey, only 80 (about 6 percent) listed positions explicitly related to digital curation (automation systems, database management, electronic or digital services, information technology), though many other positions may involve digital curation activities.

Information on the career directions of recent graduates from Syracuse University’s Certificate of Advanced Study (CAS) in Data Science is also available. Launched in 2008, the CAS is a 15-credit graduate certificate that may be pursued either as a specialization within a master’s degree or as a stand-alone program. The following information (Elizabeth Liddy, 2012) although numbers are small, illustrates the range of career paths that are becoming open to graduates with credentials in digital curation. Within 3 months of graduating, six of the eight graduates had accepted employment or entered graduate study as:

- A science research support librarian at a university-based research center;

- A digital curation librarian at a large public university;

- A metadata librarian at a small private college;

- A data coordinator at a private consulting and design company;

- A data, network, and translational research librarian at a university-based health sciences center; and

- A medical school student at a private university.

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign also began a specialization in data curation within its library and information science master’s degree program in 2007, with 63 graduates completing the specialization as of December 2012. Placement data for 83 percent of these graduates also confirms that curation professionals are filling positions in many types of organizations in a range of roles. Just under half have taken positions in academic settings in libraries at colleges and university across the country. The next largest group has been placed in the corporate sector, followed by a segment working in museums and other cultural heritage institutes, national data centers, and digital humanities and scientific research institutes. The more than 50 position titles are suggestive of how curation jobs are being formalized, ranging from data curator, data management consultant, research data librarian, and digital preservation librarian to data analyst, digital asset manager, and information architect (Palmer et al., 2014). A few graduates from Indiana University’s School of Informatics have been placed in explicitly data-oriented positions with titles such as data analytics consultant and database and systems manager, with a range of other types of positions, many of which are designated software and systems developers and designers (Fox, 2012).

Data on placement from students who have completed certificate programs and professional LIS degrees is incomplete. Even less is known about the impacts of continuing education programs, short courses, and workshops on participants’ careers. Further, digital curation education and training programs are so new that while some data on initial job placements for graduates are available, data on long-term career trajectories

are lacking. More information on placements will contribute to estimates of demand for the workforce in digital curation.

3.4 Estimating Future Demand: Government Statistics

The effort to estimate future demand for the workforce in digital curation is again stymied by the lack of complete government statistics. However, some insight can be gained by studying the BLS data that are available. BLS makes occupational projections for over 700 job categories and 300 industries every 2 years, for the upcoming 10 years. As discussed in Section 3.1, none of the jobs in the BLS SOC is titled “Digital Curation.” As a result, future demand for the digital curation workforce can only be approximated by examining employment projections for computer occupations and a few other occupations that are strongly related to digital curation.

BLS provides occupational outlook information to the general public and to analysts; the latest Occupational Outlook Handbook was published in March 2012, based on the period from 2010 to 2020. Data used for the occupational projections are gathered for 22 major occupational groups and 749 occupations based on the SOC. Digital curation is likely to be concentrated in four major occupational groups: (1) Business and Financial Operations (Matrix Code 13-0000); (2) Computer and Mathematical (15-0000); (3) Life, Physical, and Social Sciences (19-0000); and (4) Education, Training, and Library (25-0000).

These four major occupational groups are expected to experience above-average growth (see Table 3-2). The fastest growth in employment (22 percent) and the highest median wage ($73,720) is projected for Computer and Mathematical occupations, but Education, Training, and Library occupations (10.60 million) will employ more workers, as will Business and Financial Operations (7.96 million) (Lockard and Wolf, 2012). These data do not directly indicate a growth in digital curation jobs, but do suggest that growth will occur.

Table 3-2 Employment and Wages of Four Major Occupational Groups and All Occupational Groups, 2010 and Projected 2020

| Occupation | Employment 2010 (millions) | Employment 2020 (millions) | Projected change (%) | Median Annual Wage ($, May 2010) |

| Business & financial operations | 6.79 | 7.96 | 17.3 | 60,670 |

| Computer & mathematical | 3.54 | 4.32 | 22.0 | 73,720 |

| Life, physical, and social science | 1.23 | 1.42 | 15.5 | 58,530 |

| Education, training, & library | 9.19 | 10.60 | 15.3 | 45,690 |

| Total, all occupations | 143.07 | 163.54 | 14.3 | 33,840 |

SOURCE: Data from Lockard and Wolf (2012).

Table 3-3 Employment Data by Occupation, 2010, and Projections for 2010-2020

| Occupation | Jobs 2010 (thousands) | Employment Change 2010-2020 | Median Annual Wage | |

| (%) | (thousands) | 2011 ($) | ||

| Computer and mathematical | ||||

| occupations | ||||

|

Computer support specialists |

607.1 | 18.1 | 110.0 | 47,660 |

|

Computer systems analysts |

544.4 | 22.1 | 120.4 | 78,770 |

|

Software developers, applications |

520.8 | 27.6 | 143.8 | 89,280 |

|

Software developers, systems software |

392.3 | 32.4 | 127.2 | 96,600 |

|

Computer programmers |

363.1 | 12.0 | 43.7 | 72,630 |

|

Network and computer systems administrators |

347.2 | 27.8 | 96.6 | 70,970 |

|

Computer and information systems managers |

307.9 | 18.1 | 55.8 | 118,010 |

| Information security specialists,web | ||||

|

developers, and computer |

302.3 | 21.7 | 65.7 | 77,970 |

|

network architects |

||||

|

Database administrators |

110.8 | 30.6 | 33.9 | 75,190 |

|

Computer and information |

||||

|

research scientists |

28.2 | 18.7 | 5.4 | 101,080 |

| Digital curation-related occupations | ||||

|

Librarians |

156.1 | 6.9 | 10.8 | 55,300 |

|

Archivists |

6.1 | 11.7 | 0.7 | 46,750 |

SOURCES: Data from BLS (2012b); Csorny (2012).

Note that each of these four major occupational groups is growing more rapidly than the aggregate of all occupations. They also have higher median wages than the aggregate of all occupations.

Table 3.3 presents BLS projections for the various categories of computer and mathematical occupations, many of which may incorporate digital curation functions, as well as for librarians and archivists.

Many of the categories of computer and mathematical occupations employ large numbers of people, and many are expected to grow by greater than the 14.3 percent national average of all occupations between 2010 and 2020. All of these occupations have median wages of greater than the U.S. median wage of $33,840, and all but one have wages at least twice the median wage. The occupations of librarian and archivist, both related to digital curation, have a smaller number of jobs. Their projected rates of growth between 2010 and 2020 are less than average, while their median annual wage is greater than average but less than twice the median wages for all occupations.

Estimating demand for the workforce in digital curation is difficult, whether for the current period or in the future. Given the nature of digital curation activities—occurring along a continuum, and conducted by many different kinds of workers holding many different job titles and undertaking those activities either as primary professional focus or as a very limited subset of their jobs—the difficulty is not surprising. The lack of direct statistics is also a challenge. Nonetheless, estimates may be made, and they reveal a clear increase in the demand for a skilled workforce in digital curation.

3.5 Automation and Future Demand

The scale of future demand for a workforce in digital curation will be affected by many factors. Some of these—the overall health and growth of the economy, governments’ increased requirements for digital curation, the continued transfer of historic records to digitized formats—need no further reflection here. One other factor invites more consideration. That is the impact that automation of curatorial tasks may have on the demand for human capital in digital curation.

Automation is already integral to digital curation, in all disciplines, domains, and sectors. Most digital curation involves some combination of human decisions and manual effort as well as automated tools and processes. How much of curation is automated and how that automation is integrated with manual tasks along the whole continuum of the workflows of curation varies a great deal. Variability in the automation of digital curation tasks derives from many sources, including the size and resources of the organizations in

which digital curation occurs, the types of systems they have in place, the volume and types of information to be curated, and the degree to which curation tasks have been integrated into other workflows and business processes. These variations can be found not only between different sectors (e.g., financial, retail, entertainment, manufacturing, health care, research, and education), but also within organizations in the same sector.

Automation is already a common element of digital curation, and it has been increasing. As the field of digital curation matures and advances, the development and adoption of standards, norms, and best practices have enabled more automation of manual curation tasks. Investments in technology, software, and system enhancements—and in the people with the requisite knowledge and skills to design and build such systems—have also furthered automation.

How will automation affect future demand for a workforce in digital curation? Clearly, effective and long-term curation of digital information is a massive and complex undertaking. It could absorb an enormous amount of human capital. Manually mediated curation is labor intensive, sometimes prone to errors or bias, and therefore ultimately expensive. Automation of more aspects of digital curation may reduce dependence on manually mediated tasks, and thus reduce some of the increase in demand for human capital, in some areas of digital curation.

The creation of metadata is a prime candidate for automation. It is an immense and essential task. In some cases, the volume of metadata required for effective documentation greatly exceeds the volume of the data being described. Yet complete metadata are crucial for the analysis of data, as well as being a research resource itself. Despite its value, manual creation of comprehensive metadata has often been disdained by data producers, seen as a distraction from the main pursuit of research or analysis. Because of the volume of metadata needed, the costs of its manual creation, and both the feasibility and appeal of automated metadata creation, this is a very likely area for further automation in digital curation.

As digital curation becomes more systematized, with the emergence of standards, software, workflows, and other tools that reduce the need for human manual effort, other curatorial tasks are increasingly automated. Naming datasets, assigning identifiers, checking for and correcting errors, and maintaining redundant copies for backup and security are other digital curation tasks that have been and are increasingly automated (e.g., Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe [LOCKSS]3 and Digital Record Object Identification [DROID]4).

Automating some digital curation activities has many advantages. Labor is by far the largest component of curation costs (see KRDS model in Section 2.8). Automation may also decrease curatorial errors and improve data quality. Automation may not only lower the cost and professional burden of metadata creation, but may even lessen the need for metadata. As artificial intelligence and other techniques get better at inferring or uncovering meaning, the required level of metadata tagging may decrease. It may be important as well to develop tools that implement standards at the time of data capture or creation, for example, electronic lab notebooks, and this might also affect the need for further curation.

_______________

4See http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/projects-and-work/droid.htm.

More automation of metadata capture, unique identification of digital objects, error detection and correction, format migration, and the like will be necessary to contain the costs of curation. It is worth noting, however, that automation of digital curation within existing research or business processes and automation of repository functions will only go so far if the process of moving data from an active system to a repository, data center, or cloud service, is not addressed at the same time. Most efforts at automating digital curation to date have focused on either building automated digital curation workflows for business and research processes or for repository functions, but not both. As studies based on the KRDS model discussed above show, the largest expense for repositories are the processes of acquisition and ingestion.

The geospatial domain provides an example of some of the benefits and also the limitations of automation. In this domain, substantial efforts have been made over the past two decades to automate some of the functions of digital curation. Early geospatial pioneers spent large amounts of time in painstaking manual digitizing, but by the 1990s automated methods had become sufficiently sophisticated and reliable. Massive collections of paper documents, including maps and images, have been successfully digitized using automated methods. Today, manual digitizing techniques are no longer taught in most courses on geospatial technology. This curatorial task has been entirely automated.

Another task in digital curation in the geospatial domain, registration to the Earth’s surface, has also been increasingly automated. The task arises frequently when images captured from satellites or aircraft must be registered accurately to allow their contents to be analyzed and combined with other data, thus greatly enhancing their value. To accomplish this task, a number of registration points are selected from the image and their Earth coordinates (often latitude and longitude) are entered into a geographic information system (GIS). A variety of techniques for rubber-sheeting, that is, stretching the image to match the Earth, are available. The task is especially difficult at global scales when registration points are not available, such as when a landscape lacks easily recognized features, as for example over the oceans or large areas of forest. Today, well-tested methods are widely available and capable of accurately warping something as crude as a photograph shot from a moving helicopter so that it matches existing maps or databases.

Other tasks of digital curation in the geospatial domain are less susceptible to automation. For example, it would be of great value to the community of scientists conducting research across many borders and languages if the systems of land classification used in different countries could be made interoperable. This is important in many domains, including research on global climate change, biological conservation, and agriculture. Toward that end, the INSPIRE (Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community) project of the European Commission is attempting to harmonize the land classification systems of each member state. Simple cross-walks (Class A in Country 1 is the same as Class B in Country 2) are easy to do, but reality is often rather more complex (Class A in Country 1 is somewhat like Class B in Country 2). Standard methods and tools for this process, often termed semantic reasoning, are being adopted, but it is likely that the task will never be fully and satisfactorily automated.

Thus, some tasks of digital curation in the geospatial domain have been successfully automated; others will continue to require expert human judgment well into

the future. Research has also produced a better understanding of the types of digital curation tasks that are not amenable to automation, such as those that require complex semantic reasoning, depend on inference to compensate for incomplete or inaccurate information, or anticipate novel ways to analyze or exploit digital resources. More broadly, the variability of progress toward automation in different aspects of digital curation in the geospatial domain suggests that progress beyond automation of generic curation tasks (metadata capture, integrity checks, error detection, etc.) may advance more effectively if handled on a domain-by-domain basis.

What, then, is the potential for automation and how will increased automation affect future demand for the workforce in digital curation? In the view of this committee, this will ultimately depend on how the work of digital curation is organized, which technical and organizational models for digital curation prevail, and what level of resources are invested in the development of the field. Clearly, the degree of human versus automated tasks in curation has important implications for the types of careers and jobs associated with digital curation and the education of the future workforce. If routine curation tasks can be automated, then it is possible that digital curation will require a smaller number of employees engaged in manual curation tasks. The experience in other areas where information technology is applied to traditional tasks, however, suggests that far from reducing employment, automation both allows specialists to advance to more sophisticated tasks and increases the overall level of employment. To achieve a high degree of automation in digital curation during the next decade, investments in standards and software development are essential. Those investments, in turn, are likely to generate demand for specialists who can design and build systems and applications that support digital curation, develop and implement standards, create and promulgate effective policies and best practices, and design and deliver the next generation of digital curation services.

3.6 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusion 3.1: Jobs involving digital curation exist along a continuum, from those for which almost all tasks focus on digital curation to those for which digital curation tasks arise occasionally in a job that is embedded in some other domain.

Conclusion 3.2: Although digital curation is not currently recognized by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in its Standard Occupational Classification, other sources of employment data identify the emergence and rapid rise of digital curation and associated job skills.

Conclusion 3.3: There is a paucity of data on the production of trained digital curation professionals and their career paths. Tracking employment openings, enrollments in professional education programs, and the placement and career trajectories of graduates from these programs would help balance supply with demand on a national scale.

Conclusion 3.4: The pace of automation and its potential impact on both the number and types of positions that require digital curation knowledge and skills is a great unknown. Automation of at least some digital curation tasks is desirable from a number of perspectives, and its potential has been demonstrated in several domains.

Conclusion 3.5: Enhanced educational opportunities and new curricula in digital curation can help to meet the rapidly growing demand. These opportunities can be developed at all levels and delivered through formal and informal educational processes. Digital learning materials that are accessible online, for example, may achieve broad exposure and possible rapid adoption of digital curation procedures.

Recommendation 3.1: Government agencies, private employers, and professional associations should develop better mechanisms to track the demand for individuals in jobs where digital curation is the primary focus. The Bureau of Labor Statistics should add a digital curation occupational title to the Standard Occupational Classification when it revises the SOC system in 2018. Recognition of digital curation as an occupational category would also help to strengthen the attention given to digital curation in workforce preparation.

Recommendation 3.2: Government agencies, private employers, and professional associations should also undertake a concerted effort to monitor the demand for digital curation knowledge and skills in positions that are primarily focused on other activities but include some curation tasks. The Office of Personnel Management should issue guidelines for specifying digital curation knowledge and skills that should be included in federal government position descriptions and job announcements. Private employers, professional associations, and scientific organizations should specify the digital curation knowledge and skills needed in positions that require them.

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). Federal Register Notice. 2014. “Standard Occupational Classification (SOC)—Revision for 2018; Notice.” Volume 79. Number 99 (May 22).

BLS. 2012a. Bureau of Labor Statistics Standard Occupation Classification. http://www.bls.gov/soc. Accessed August 16, 2012.

BLS. 2012b. Employment Projections 2010-2020. Last modified February 1, 2012. http://www.bls.gov/emp/.

Csorny, L. 2012. Computer occupational employment statistics and projections. Presented at public session of the Study Committee for Future Career Opportunities and Educational Requirements for Digital Curation, Board on Research Data and Information, National Research Council, Washington, DC, May 3.

Fox, G. 2012. Data analytics and its curricula. Presented at Microsoft eScience Workshop, Chicago, October 9.

Indeed.com. 2012. Job Trends. www.indeed.com/jobtrends. Accessed August 17, 2012.

Levanon, G., B. Colijn, B. Cheng, and M. Paterra. 2014. From Not Enough Jobs to Not Enough Workers: What Retiring Baby Boomers and the Coming Labor Shortage Mean for Your Company. Research Report R-1558-14-RR. The Conference Board, Inc., September.

Liddy, E. 2012. Digital curation as a core competency. Presented to the Symposium on Digital Curation in the Era of Big Data: Career Opportunities and Educational Requirements, Board on Research Data and Information, National Research Council, Washington, DC, July 19.

Lockard, C. B., and M. Wolf. 2012. Occupational employment projections to 2020. Monthly Labor Review (January):84-108.

Maatta, S. L. 2011. Explore the data. Library Journal. http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2011/10/placements-and-salaries/2011-survey/explore-the-data-2/.

Maatta, S L. 2012. A job by any other name| LJ’s placements and salaries survey 2012. Library Journal. http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2012/10/placements-and-salaries/2012-survey/a-job-by-any-other-name-ljs-placements-salaries-survey-2012/.

Miller, S. 2012. The future of work. Presented to the Symposium on Digital Curation in the Era of Big Data: Career Opportunities and Educational Requirements, Board on Research Data and Information, National Research Council, Washington, DC, July 19.

Palmer, C. L., C. A. Thompson, K. S. Baker, and M. Senseney. 2014. Meeting data workforce needs: Indicators based on recent data curation placements. In iConference 2014 Proceedings, March 4-7, 2014, Berlin, Germany. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/47308.