4

EVIDENCE FOR DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE INTERVENTIONS FOR PREVENTING PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

The committee was charged with conducting a systematic review and critique of Department of Defense (DOD) resilience and reintegration programs and prevention strategies related to the psychological health of service members and their families. This chapter discusses various DOD policies, programs, and services intended to enhance psychological health and prevent psychological disorders among service members and their families. It describes the nature of the interventions and reports on empirical studies that provide evidence concerning their effectiveness. Given the fast-track nature of the committee’s work, the committee conducted a literature review sufficient to highlight some of the interventions that address the psychological health concerns identified in the statement of task. It did not attempt to create a catalog of all of the DOD prevention interventions in those areas.

The chapter begins with an overview of DOD prevention interventions. It includes findings from a recent comprehensive assessment of DOD psychological health and traumatic brain injury (TBI) programs. The overview also summarizes the interventions that are the subject of this committee’s review. The sections that follow describe those interventions and their evidence and are organized by topical areas defined by the statement of task: resilience-related programs, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide (and depression), substance use disorders (including recovery support), reintegration, military sexual assault, and family-focused programs. The organizational structure aligns with the committee’s statement of task, but it is imperfect as some interventions address more than one health concern. For example, RESPECT–Mil, a primary care program designed to encourage early identification of depression and PSTD, is discussed in the section on suicide prevention as depression and PTSD are both risk factors for suicide.

OVERVIEW OF DOD PREVENTION INTERVENTIONS

Recent Review of DOD Psychological Health Programs

In an effort to develop a systematic list of DOD’s numerous programs that address various components of psychological health along the resilience, prevention, and treatment continuum, the RAND Corporation created a comprehensive catalogue of programs currently sponsored or funded by DOD to address psychological health and TBI. The catalogue, which is available in hardcopy and in an online searchable database, provides detailed descriptions of each program. As of November 2013, the electronic database contained 226 programs (RAND Corporation, 2013). Of the 226 programs, RAND classifies 94 as addressing the area of prevention (which includes resilience) (RAND Corporation, 2013). Appendix H shows RAND’s list of prevention/resilience programs and three classification elements reported by RAND: the

phase of deployment the intervention pertains to, whether it is a family-related intervention, and whether the intervention is based on evidence, as reported by program staff interviewed. RAND did not independently review or assess the strength of the evidence base employed. Fewer than half of the prevention programs shown are reported to be based on evidence.

RAND’s assessment (Weinick et al., 2011) found no centralized mechanism to catalogue all these programs and track which are effective, whether they meet the needs of the target audience, whether there are any gaps in program activity areas covered, and whether the programs need more resources. Furthermore, while there are many programs addressing a wide array of outcomes, many are duplicative in nature (both within and across service branches), few are based on evidence, and few measure outcomes. Programs are evaluated infrequently—according to interviews with program staff, fewer than one-third of the programs in any branch of service had had an outcome evaluation in the previous 12 months. For those programs conducting an evaluation, there was variation in the rigor of the evaluation, including such things as whether it was conducted internally or by an independent party, whether it had a control group, whether it examined both processes and outcomes, and the appropriateness of the metrics used. RAND emphasized that the negative consequences of not having a process to systematically develop, track, and evaluate programs include the proliferation of untested programs that are developed without an evidence base, inefficient use of resources, added cost and administrative inefficiencies, and the increased likelihood of failing to identify a potentially harmful program. Similarly, Meredith et al. (2011), in a monograph on resilience programs in DOD, found no standard measure of resilience or outcomes across programs, a situation that makes it difficult to compare programs and approaches that share a common goal.

The Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCOE) was established in 2007 to “assess, validate, oversee and facilitate prevention, resilience, identification, treatment, outreach, rehabilitation, and reintegration programs for psychological health and traumatic brain injury” (DOD, 2010a) for DOD. The committee did not assess DCOE’s role in psychological health programming across the department.

Selecting a Sample of Programs for Assessment

Deciding that there was little value in duplicating RAND’s efforts and considering the fast-track nature of this study, the committee concentrated its assessment on a sample of DOD prevention programs and interventions. The committee focused on interventions with strong relevance to the targeted areas of this study and for which significant information and research findings were available in the literature. As such, the interventions discussed in the section should not be considered representative of all DOD prevention interventions.

There is no consensus on exactly how “resilience” should be defined (Meredith et al., 2011). Echoing the recent RAND report Promoting Psychological Health in the U.S. Military (Meredith et al., 2011), this committee defines psychological resilience as the ability to cope with or overcome exposure to adversity or stress. However, the use of the term “resilience” in the report reflects the inconsistencies in the state of the evidence within the field and differences across DOD programs.

The capacity for resilience can be supported and enhanced across multiple systems, including within individuals, families, communities and cultural contexts, including the military unit or larger community. Resilience can occur along the continuum of response to stress, from the lack of development of psychological conditions such as PTSD and depression in response to trauma, through the ability to recover from a resultant psychological condition such as PTSD without developing a chronic condition with associated additional comorbidities (such as depression and substance abuse) and chronic functional impairment. Thus, enhancing resilience as a means of prevention can occur prior to exposure to stressors (either at a universal or selective level for those at higher risk), to decrease the development of persistent distress and psychological conditions, or can occur after initial symptoms occur to prevent chronic conditions (e.g., intervening for acute stress disorder to prevent PTSD) or can occur along the early treatment pathways (to prevent chronic disability and comorbid conditions and promote rapid recovery once PTSD has developed). As such, resilience is a concept that potentially comes into play in all phases of the deployment cycle.

In Promoting Psychological Health in the U.S. Military, Meredith et al. (2011) first examined the evidence base for resilience and then looked at the extent to which specific factors were reflected in DOD resilience-promotion programs. They reported that factors promoting psychological resilience can operate at various levels: the individual (positive coping and affect, positive thinking, realism, behavioral control, physical fitness, and altruism), the family (communication support, nurturing, emotional ties, and adaptability), the organization or unit (positive command climate, cohesion, and teamwork), and the community (cohesion, connectedness, belonging, and collective efficacy). Meredith et al. (2011) also reported that, generally speaking, most programs in the military emphasize factors with the strongest evidence in the literature. The resilience-promotion factors found in DOD programs at the individual level are positive thinking, positive coping, behavioral control, positive affect, and realism training. At the unit level a majority of programs incorporate positive command climate and teamwork. Many of the programs use enhancing family communication to promote resilience; however, there is more empirical evidence for the effectiveness of enhancing family support than for the effectiveness of enhancing family communication. Belongingness (which includes social integration and group membership) was the community factor most widely used by programs.

Concerning measures of effectiveness, Meredith et al. (2011) found no standard measures of resilience or outcomes used across DOD resilience programs. Moreover, although some of the programs have been widely disseminated and shown by research to be effective in non-military populations, by and large there is little evidence that these military programs truly build resilience. Meredith and colleagues reviewed 270 documents and found only 11 with a randomized controlled design. Three programs—Battlemind, Comprehensive Soldier Fitness, and Combat Operational Stress Control—are discussed in more detail below. See Chapter 5, What Should Be Measured?, for additional discussion about measuring the concept of resilience.

Battlemind

Battlemind, which is now called Resilience Training, is an Army program designed to foster resilience by teaching self-confidence and mental toughness in the context of deployment and transitioning home. The term “battlemind” is defined as the soldier’s inner capacity to face fear and adversity with courage. Developed by researchers at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Battlemind is a psycho-educational intervention that uses a cognitive and skills-based

approach to normalize reactions to operational stress, to build resilience, to ease the transition to home, and to promote self-recognition of psychological problems, help seeking, and identification of difficulties in others (Adler et al., 2009a,b). Prior to the widespread implementation of the program, randomized trials showed that the intervention had a positive effect on soldiers’ adjustment from combat, although the effect sizes were small (Adler et al., 2009b). Battlemind was launched in 2007 and mandated Army-wide.

There are several Battlemind modules,1 the most prominent of which are Battlemind Debriefing and Battlemind Training. Battlemind Debriefing is used at various intervals during combat deployment and sometimes post-deployment to deal with deployment’s cumulative effects. Among its goals are to identify the traumatic events that have placed a significant demand on unit members; to normalize thoughts and reactions; to discuss anger, withdrawal, and sleep problems; and to emphasize what individuals can do for themselves and their comrades. The debriefing seeks to restore a sense of duty and honor to the participants in order to enable them to proceed with their mission (Orsingher et al., 2008). Unlike other types of psychological debriefing, Battlemind Debriefing minimizes the degree to which traumatic events are recounted in order to avoid re-traumatization (Adler et al., 2009a).

Battlemind Training, on the other hand, is expressly designed for the post-deployment period. Based on Walter Reed Army Institute research (Adler et al., 2009a), it is a 1-hour psycho-educational intervention led by a psychological health professional which takes a cognitive and skills-based approach to informing military personnel about the post-deployment transition. It reinforces the point that specific skills that serve individuals well in combat need to be reframed and adapted for the transition home.

Several studies have evaluated the effectiveness of Battlemind. A randomized controlled trial involving 2,297 soldiers looked at Battlemind Debriefing and Battlemind Training interventions that were held 1 month post-deployment. The study found that Battlemind had positive effects on psychological health when compared to stress education, but only for those with high levels of combat exposure. More specifically, the study found that at 4 months followup both modules of Battlemind led to fewer symptoms of PTSD, less depression, and fewer sleep problems in those with high levels of combat exposure (Adler et al., 2009a). Another controlled trial of a 1-hour Battlemind training module carried out at 1 to 6 months post-deployment found fewer PTSD and depression symptoms at the 6-month follow-up; these benefits applied to participants as a whole, were of a small to medium effect size for PTSD symptoms (d=0.3 for PTSD Checklist (PCL) change score compared to a survey-only control condition), and were not restricted to those with high levels of combat exposure, although there was a high rate of loss to follow-up at 6 months (67 percent), which limited conclusions (Castro et al., 2012). The study also found less stigma surrounding help seeking immediately after the Battlemind session but not at follow-up. A UK version of Battlemind Training, described as more didactic in nature and lasting about 45 minutes, was studied in a cluster randomized controlled trial and showed no difference in PTSD and other psychiatric symptoms, although it did find a modest lowering of self-reported binge drinking (Mulligan et al., 2012). The control group was a standard postdeployment stress and homecoming brief and thus was more active than the survey-only condition used in the Castro et al. (2012) study; limitations of the study included relatively

____________________

1 Modules have been created for delivery at different stages of deployment (e.g., pre- or post-deployment) and for different personnel (e.g., soldiers, leaders, spouses).

minimal PTSD symptoms overall (mean PCL 23.6) and some crossover between the conditions. Some of the Battlemind modules have been converted from a standalone program into components of Comprehensive Soldier Fitness.

Comprehensive Soldier Fitness

In 2009 the Army launched the $125 million Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program (U.S. Army, 2009), the largest universal prevention program of its kind. At present it has already reached 1 million soldiers (Lester et al., 2011b). The goals of the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness (CSF) program are to prevent adverse psychological health consequences of trauma exposure—most notably, PTSD and depression—by increasing resilience in service members before deployment. The CSF program is based, in part, on the Penn Resiliency Program, which was developed by Martin Seligman at the University of Pennsylvania (Cornum et al., 2011). The Penn Resiliency Program is based on positive psychology as well as on cognitive behavioral theories of depression, and it includes training in assertiveness, negotiation, social skills, creative problem solving, the use of optimism and positive explanatory approaches, and decision making.

The CSF resilience-building program has four components that are designed to enhance service members’ mental, spiritual, physical, and social capabilities: (1) master resilience training, a 10-day, hands-on, face-to-face training course that includes the principles of positive psychology (Reivich et al., 2011); (2) comprehensive resilience modules (formerly known as Battlemind), which are training modules that focus on specific resilience skills using precepts of positive psychology, cognitive restructuring, mindfulness, and research on posttraumatic stress, unit cohesion, occupational health models, organizational leadership, and deployment in order to prepare service members for military life, combat, and transitioning home; (3) the global assessment tool (GAT), a confidential online 105-question survey that must be taken annually; and (4) institutional resilience training, which is expected to occur at every level of the Noncommissioned Officer Education System and the Officer Education System (U.S. Army, 2013b). Master resilience training for noncommissioned officers and mid-level supervisors is a “train the trainer” component of CSF for sergeants to use with their troops. Versions of the program are also available for military families and Army civilians, although this committee found no evidence of their implementation with these groups. The CSF GAT measures psychosocial well-being in four domains: emotional fitness, social fitness, family fitness, and spiritual fitness. Results of the GAT are used to refer soldiers to programs aimed at enhancing their strengths and addressing their weaknesses, for example, training in flexible thinking if scores in this area are lower than the norm. A similar instrument, the Family GAT, is being developed for soldiers’ spouses and partners to provide advice about possible resources for building emotional assets.

Internal Evaluation of CSF

Although evaluations that were conducted by CSF staff and were not subject to peer review have demonstrated statistically significant improvement in some GAT subscale scores, the effect sizes have been very small, with no clinically meaningful differences in pre- and posttest scores. Accordingly, it is difficult to argue there has been any meaningful change in GAT scores as a result of participation. For example, in The Comprehensive Soldier Fitness Program Evaluation Report #3: Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Master Resilience Training on Self-Reported Resilience and Psychological Health Data (Lester et al., 2011b), in a pre–post

comparison the maximum effect size (partial η2) of any outcome measured by the GAT was found to be 0.002 after exposure to the intervention. The only resilience or psychological health measures that saw significant improvement post-exposure were emotional fitness (a 1.31 percent improvement; 0.002 partial η2) and social fitness (a 0.66 percent improvement; 0.000 partial η2) (Lester et al., 2011b).

While Lester et al. (2011b) cite these figures as evidence of CSF’s effectiveness for prevention, this committee does not find these results meaningful, given the low level of improvement and the very small effect size. External reviews, discussed below, have raised similar questions concerning the effect sizes of reported findings and related problems in accurate interpretation of the impact.

More recently, in another internal non–peer-reviewed report, The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program Evaluation Report #4: Evaluation of Resilience Training and Mental and Behavioral Health Outcomes, Harms et al. (2013) examined psychological health diagnosis outcomes for 7,230 soldiers who received the GAT before Master Resiliency Training was initiated (October 2010) and again approximately 6 months later (about April 2011) and who consented to use of their data for research. The researchers compared five psychological health diagnoses recorded in the U.S. Army Medical Department’s Patient Administration Systems and Biostatistics Activity (anxiety, depression, PTSD, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse) 3 months after return from deployment or completion of the second GAT for the 4,983 who had received the training (80 percent of whom had deployed) versus the 2,247 who had not (72 percent of whom had deployed). Findings revealed no change in the GAT factors and no difference in diagnosis among those receiving the intervention. Therefore, the subsequent mediation analysis performed by the authors cannot be interpreted as evidence of intervention/program impact.

External Reviews of CSF

In their review of CSF, Steenkamp et al. (2013) observed that the program that served as the blueprint for CSF, the Penn Resiliency program, did not, according to a meta-analysis, produce powerful effects in its own target, preventing depression in civilian adolescents and schoolchildren. The meta-analysis found that although the program reduced symptoms of depression, the effect size was small, and the program did not prevent, delay, or lessen “the intensity or duration of future psychological disorders” (Brunwasser et al., 2009, p. 1051). Prevention trials in adolescents and children find that an improvement in subclinical levels of depression is a more likely outcome than the prevention of a depression diagnosis in the future (Stice et al., 2009). With regard to the prevention of PTSD, Steenkamp and colleagues assert that no data at all support the effectiveness of the Penn Resiliency Program for adults; instead, they say, the best evidence for PTSD prevention can be found not in universal prevention programs like CSF, but in selective and indicated prevention programs, whose strongest effects are in preventing chronic PTSD in those who are already self-reporting clinically diagnosable stressrelated symptoms (Bryant et al., 1998). Steenkamp and colleagues also criticized the GAT as not being designed to assess PTSD symptoms; it assesses only strengths and problems in emotional, social, family, and spiritual domains. “Thus the program evaluation could not adequately assess CSF’s success in preventing PTSD” (Steenkamp et al., 2013, p. 509). Steenkamp and colleagues also question the underlying assumption of the program that increasing resilience prevents onset of PTSD, noting that “it is possible to be psychologically high functioning and still develop PTSD” (p. 510).

In their article “The Dark Side of Comprehensive Soldier Fitness,” Eidelson and colleagues (2011) emphasize that CSF was initiated without the use of pilot testing to determine program effectiveness. Like Steenkamp and colleagues, they criticize the application of the Penn Resiliency program in the face of the small effect sizes found in the meta-analysis by Brunwasser et al. (2009). Eidelson and colleagues also criticized the lack of CSF review by an independent ethics board, especially in light of the mandatory nature of the program. They assert that resilience training may “harm our soldiers by making them more likely to engage in combat actions that adversely affect their psychological health” (Eidelson et al., 2011, p. 643).

Smith (2013) critiques the CSF program as potentially causing harm. She observes that CSF’s emphasis on positive emotions and reducing the frequency of negative emotions could be detrimental. Service members experiencing negative feelings could feel “marginalized and demoralized for failing to cope using CSF’s strategies” (p. 244). To support this view, Smith cites a study by Norem and Illingworth (2004) finding that when a positive mood is induced, individuals who are pessimists display decreased ability to problem-solve. Smith also argues that CSF shifts responsibility for psychological health away from external causes, such as multiple deployments and prolonged periods of combat stress, and onto the individuals, who blame themselves for not preventing their own disorder. She points out that service members who experience self-blame are at risk for further mood disturbances and poorer quality of life (Smith, 2013).

Combat Operational Stress Control

During the past decade the Marine Corps has pioneered the development of the Combat Operational Stress Control (COSC) program whose goals are to prevent, identify, and treat combat and operational stress problems. Although the COSC program is being implemented in the Marine Corps and Navy, the generic concept of combat operational stress control informs activities in other service branches, albeit with different approaches. This section describes the Marine Corps and Navy program only. The program is taught and reinforced at multiple points during careers and deployment cycles. Its three major components are

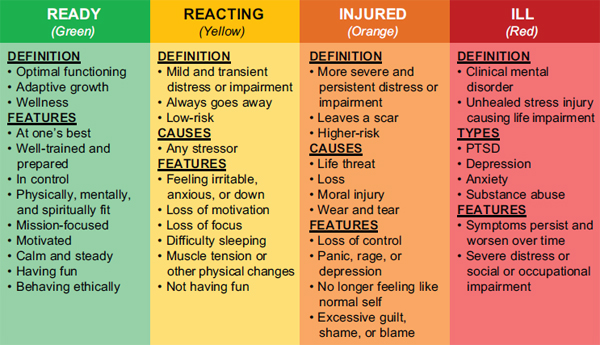

1. The perception of stress as a continuum, according to a model that uses a color-coded tool to identify who is ready (green zone), reacting (yellow zone), injured (orange zone) and ill (red zone) (Nash, 2011). See Figure 5-1. The goal of COSC is to keep soldiers in the green zone or to treat them so they can return to the green zone.

2. The promotion of five core leadership functions: to strengthen service members; mitigate stressors; identify stress reactions, injuries, and illnesses; treat stress injuries and illnesses; and reintegrate stress casualties (Nash, 2011).

3. The oversight of combat operational stress first aid, a toolkit for non-medical care of stress injuries.

The Marine Corps requires that a percentage of leadership personnel in each operational unit be trained and certified in all three components of COSC under the related OSCAR (Operational Stress Control and Readiness) program. OSCAR is carried out by three different types of trained individuals: OSCAR “mentors,” leaders who are strong role models and are ready to intervene and mentor other Marines with stress problems; OSCAR “extenders,” who are chaplains, medical staff, and religious support specialists who can spot operational stress and provide a bridge to treatment by the third type of trained individual; and OSCAR psychological

health personnel, who are embedded in operational units to provide formal psychological health services to troops and to provide training, oversight, and consultation to commanders. OSCAR is not an intervention per se, but rather the use of trained professional and leadership teams that promote healthy social norms and facilitate access to treatment.

FIGURE 4-1 Stress continuum model sponsored by the Marine Corps.

SOURCE: Nash, 2011.

The only formal study of the COSC program is a baseline assessment of 553 Marines from 4 different bases who were participating in COSC (Momen et al., 2012). In this baseline assessment, 43.5 percent of the sample reported that their most recent deployment was still causing stress, and 31 percent reported that the stress affected their job performance. The most common views of combat stress reactions were that they are treatable (70.5 percent), normal (68.2 percent), can be managed (57.4 percent), and are harmful to career (46.7 percent). The survey also reported on attitudes toward help seeking and the treatment of stress-related disorders and found that fears of treatment seeking included a lack of confidentiality, a loss of trust from their unit or being treated differently by members of their unit, harming their careers, and having a preference to solve their own problems. A formal evaluation of COSC/OSCAR, including its impact on Marine mission readiness, unit cohesion, stigma, and stress burden, is being conducted by the RAND Corporation and will be published in Spring 2014.

BOOT STRAP

BOOT STRAP (Bootcamp Survival Training for Navy Recruits—A Prescription) is a program designed to help recruits cope with the emotional challenges of training. There are two studies that have examined the effectiveness of BOOT STRAP. Interestingly, one study (Williams et al., 2004) randomly assigned delivery of a psychologist-led weekly 45-minute group intervention for only half of the 25 percent of recruits who scored at higher risk based on the Perceived Stress Scale (30 or above) or the Beck Depression Inventory (18 or above) at baseline. The manual uses a cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) approach to enhance coping skills, belonging, team building, and stress management and to reduce the thought distortions associated with depression. The remaining high- and low-risk recruits participated in a control condition with weekly education (e.g., on personal hygiene) but lacking CBT strategies or a focus on support. Among the high-risk group, a greater proportion of the intervention group (86

percent) than the control group (74 percent) completed basic training; the completion rate among the intervention group was comparable to the 84 percent completion rate among the remaining 75 percent of recruits who had been deemed lower risk (Williams et al., 2004). In a follow-up study (Williams et al., 2007) of 1,199 Navy recruits cluster-randomized to either intervention or control status, the researchers did not find significantly different separation rates at 2 years or significantly different symptoms by the end of basic training (with differences in rate but not endpoint change in both studies), but they did find that those who trained in the more competitive summer “surge” recruitment months completed basic training at a significantly higher rate (10.3 versus 5.2 percent separation) (Williams et al., 2007). This program does show some feasibility and potential efficacy for the targeting of skills for those identified at risk upon initial entry into the military.

This section summarizes a body of research on several clinical interventions designed to prevent the onset of PTSD after the traumatic exposure has occurred, some of which interventions have been demonstrated to be effective. These interventions can resolve PTSD symptoms effectively, possibly decreasing the likelihood of chronic and disabling outcomes in service members.

After exposure to a traumatic event, although rates vary based on many factors—approximately one-third of men and one-half of women—develop PTSD (North et al., 2005). Although symptoms may begin in the immediate aftermath of exposure to the traumatic event, PTSD is not diagnosed until at least 1 month later, most typically in the 1 to 3 months posttrauma. Frequently, PTSD is preceded by acute stress disorder (ASD), which can be diagnosed in the first 4 weeks post-trauma, after which PTSD criterion may be met (APA, 2013). This time separation is meant to separate those for whom symptoms are transitory from those who develop PTSD, which can become more chronic, and it affords the opportunity for early intervention to prevent PTSD in trauma-exposed individuals. Most prevention trials have tested interventions in trauma-exposed civilians. The main outcome measures have been either prevention of PTSD diagnosis or a reduction in PTSD symptomatology. This section evaluates the evidence for psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy interventions for the prevention of PTSD. For more information about PTSD prevention and treatment programs in DOD and VA, see Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Military and Veteran Populations (IOM, 2012). A second volume of that report, which will include an assessment of PTSD programs, will be released in summer 2014.

Psycho-Social Interventions

The strongest evidence for prevention of PTSD comes from studies of individuals with ASD who are given trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Eighty percent of individuals with ASD proceed to develop PTSD (Harvey and Bryant, 1998). Three randomized controlled trials in Australia by Bryant and colleagues (Bryant et al., 1998, 2003a, 2005) found that CBT prevents onset of PTSD in trauma-exposed individuals2 who meet the criteria for ASD. The CBT

____________________

2 Individuals were civilians who had experienced motor vehicle accidents, industrial accidents, nonsexual assault, or mild traumatic brain injury.

consisted of five to six sessions of individual therapy that included education about trauma reactions, progressive muscle relaxation training, exposure to traumatic events, cognitive restructuring of fear-related beliefs, and graded exposure to avoided situations. Individuals were started on CBT within 2 weeks of trauma and were followed until 6 months post-trauma, at which point structured diagnostic interviews were conducted. In the first study Bryant and colleagues found fewer cases of PTSD in the CBT group (17 percent) than in the supportive counseling group (67 percent) (Bryant et al., 1998). Similar findings were reported in the second study, with fewer cases of PTSD in the CBT group (17 percent) than in the supportive counseling group (58 percent) (Bryant et al., 2003a). In the third study, subjects were randomized to supportive counseling, CBT, or CBT with hypnosis (including focused attention and muscle relaxation) for 15 minutes just prior to the imagined exposure exercises, the purpose of which was to help patients engage fully in the trauma exposure (Bryant et al., 2005). Although not significantly different at end of treatment or at 6 months post-treatment in the intent to treat analysis, fewer subjects in the CBT and CBT–hypnosis groups developed PTSD than subjects given supportive counseling; the findings were limited by a small sample size and a higher dropout rate in the CBT conditions. CBT–hypnosis yielded greater reduction than CBT in reexperiencing symptoms at post-treatment. These studies figured prominently in a meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration, which concluded that individual trauma-focused CBT was effective at PTSD prevention for individuals with acute traumatic stress symptoms (Roberts et al., 2012). Still, the authors suggested additional study in the form of larger, high-quality trials with longer follow-up intervals. Other types of psychotherapy, such as trauma-focused group therapy, eye movement desensitization, and non-trauma-focused CBT, were not found effective in prevention of PTSD.

Two subsequent studies by the Australian research team are noteworthy. A 4-year followup of patients studied in an earlier trial (Bryant et al., 1998) found that PTSD rates continued to be lower in patients treated with trauma-focused CBT than those treated with supportive therapy (Bryant et al., 2003b). A separate randomized controlled trial compared the efficacy of the two main elements of trauma-focused CBT—exposure therapy and cognitive therapy—and found exposure therapy to be superior in preventing cases of PTSD in subjects with ASD (Bryant et al., 2008). In contrast, another study comparing exposure therapy and cognitive therapy found them to be similarly effective in reducing the prevalence of PTSD (Shalev et al., 2012). One difference between these two studies is that Bryant and colleagues (2008) required ASD at the time of recruitment, while Shalev et al. did not require dissociation or avoidance, but rather required at least two of the three DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis clusters without the 1-month time criterion.

Psychotherapy for civilians exposed to trauma—a group composed of people with and without ASD—shows less impressive results than psychotherapy for patients with ASD. In a meta-analysis for the Cochrane Collaboration, Roberts and colleagues (2010) evaluated eight randomized controlled trials of multi-session psychotherapies and found no evidence of PTSD prevention. In fact, they found that a trend for increased PTSD symptoms at 3- to 6-month follow-ups. Because of the potential for harm and the lack of evidence of a main effect, the authors concluded that no psychotherapy intervention can be recommended for routine use. The psychotherapies under study were trauma-focused CBT individual therapy, stress management/relaxation, trauma-focused CBT group therapy, eye movement desensitization, and non-trauma-focused CBT group therapy.

Psychological debriefing, including critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), was created for use with rescue workers in the aftermath of potentially traumatic events. It includes a variety of single-session individual and group interventions that involve revisiting the trauma for the purpose of encouraging trauma-exposed persons to talk about their experiences during the trauma; to recognize and express their thoughts, emotions, and physical reactions during and since the event; and to learn coping methods. Specially trained debriefers lead the sessions, which usually focus on normalization of symptoms, group support, and provision of psychoeducation and information about resources (IOM, 2012). Most randomized controlled trials that have examined psychological debriefing for the prevention of PTSD have used onetime debriefings of victims of motor vehicle accidents or crimes, such as rape. Numerous reviews and meta-analyses of these studies have determined that this treatment is ineffective and occasionally harmful because it can cause re-traumatization or secondary exposure to trauma through forced discussion of trauma details experienced by the individual or others in group format (McNally et al., 2003; Rose et al., 2002). A more recent study (Adler et al., 2008) randomized 1,050 soldiers who served in Kosovo as peacekeepers into 62 groups that were subjected to 3 conditions: critical incident stress debriefing (the most common form of psychological debriefing), stress education, and wait list. No differences were found between groups in any of the measured psychological health outcomes, although it should be noted that soldiers in the study experienced relatively few traumas. In summary, psychological debriefing has not been shown to prevent PTSD, and the VA/DOD guidelines (VA and DOD, 2010) and the Cochrane review of this topic (Rose et al., 2002) have stated that compulsory psychological debriefing is contraindicated.

A different approach, prolonged exposure therapy, is based on fear-extinction models of PTSD and combines imagined and situational exposure through repeated confrontation of traumatic memories and avoided reminders to allow processing of the trauma, fear extinction (reduction in fear responses to trauma memories and reminders), and reduction in overgeneralization of fear contexts over time (e.g., learning that darkness alone does not mean another attack will occur) (VA, 2013). A key difference between this and psychological debriefing is that the exposures are repeated and maintained until anxiety diminishes. Rothbaum et al. (2012) examined whether an early intervention with a three-session modified version of prolonged exposure therapy following a traumatic event could reduce the onset of PTSD. Participants were trauma survivors found in an emergency department and were assigned to receive either prolonged exposure therapy or a symptom assessment only within 12 hours of experiencing the traumatic event. At 4 weeks following the intervention, there was no statistical difference in PTSD diagnosis (using the PTSD Symptom Scale Interview, PSS-I) between the two groups: 54 percent of the intervention group and 49 percent of the assessment-only group did not meet the criteria for PTSD at 4 weeks (p=.60). A treatment difference did emerge over time, however, as 74 percent of the intervention group and 53 percent of the assessment-only group (p=.04) did not meet the criteria for PTSD at 12 weeks. The effectiveness of the intervention varied according to the type of trauma. Those in the prolonged exposure group who had experienced sexual trauma saw significantly more improvement at both four (p=.004) and 12 weeks (p=.05) compared to the assessment-only group. Among those who experienced a transportation trauma or a physical assault, the prolonged exposure group did not see a significantly better outcome than the assessment only group at either 4 or 12 weeks (Rothbaum et al., 2012). These data provide a preliminary indication that the evidence-based approach of prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD may also be helpful as an early intervention strategy to

prevent chronic PTSD development; additional research is needed to clarify the optimal length of treatment and target population for this approach.

Patients often take months or years to seek treatment for their PTSD (Kessler et al., 1995). Thus Zatzick and colleagues (2013) sought to deliver psychiatric care soon after the traumatic injury occurred in order to determine the ameliorative effects of such immediate treatment. Their study, which looked at 207 hospitalized injury survivors, was a stepped-care intervention trial of psychopharmacology and cognitive behavioral therapy. The CBT component included psychoeducation, muscle relaxation, cognitive restructuring, and graded exposure. Stepped care consists of case management targeted to the intensity of need and coordinated across different care settings by a team of psychological health professionals, including those with a master’s degree in social work and nurse practitioners. Participants were initially screened in the hospital by the PTSD Checklist Civilian version (PCL–C). Patients with a score of at least 35 on the PCL–C were rescreened with a second PCL–C in the days and weeks post-discharge. Patients who again scored at least 35 were randomly assigned to stepped care or usual care. Symptoms of PTSD and functional impairment were assessed at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months postinjury. At the 6-, 9-, and 12-month assessments, recipients of stepped care had clinically and significantly reduced symptoms of PTSD as determined by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Recipients of stepped care also exhibited significant improvements in physical function as measured by the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Physical Component Summary. The study concluded that a stepped-care intervention lowers PTSD symptoms and improves physical functioning during the first year post-injury, and provides an example of systematically adapting interventions based on screening.

Pharmacotherapy

The beta-adrenergic antagonist propranolol has been tested as a preventive intervention under the rationale that excessive noradrenergic activity is associated with PTSD. Although initial data in a small randomized trial of propranolol compared to placebo led to some suppression of physiologic reactivity to trauma cues when delivered in the emergency department 6 to 12 hours post-trauma and continued for the next 10 days, propranolol showed no significant reduction in PTSD symptoms 1 and 3 months thereafter (Pitman et al., 2002). Furthermore, a follow-up randomized controlled trial by the same group (Hoge et al., 2012) with propranolol dose maximized up to 240 mg/day for 19 days failed to find a significant difference in PTSD diagnosis, symptoms, or physiologic reactivity at 4 and 12 weeks post-trauma, and the authors concluded that propranolol could not be recommended as a PTSD prevention strategy in the acute aftermath of trauma. These findings were consistent with Stein and colleagues (2007), who also failed to find evidence for efficacy in PTSD prevention of 14 days of propranolol or gabapentin administered within 48 hours of traumatic injury compared to placebo in a small randomized controlled trial.

Hydrocortisone also has been tested under the rationale that low cortisol levels are associated with PTSD. Two small clinical trials found lower rates of PTSD at long-term followup (Schelling et al., 2001, 2004). In a third study by the same group, hydrocortisone given over a 4-day taper resulted in better postoperative adjustment after cardiac surgery, on the basis of measures of quality of life, stress, and PTSD (Weis et al., 2006). A small placebo-controlled randomized control trial (RCT) of 25 civilians with acute stress symptoms found the best results

at 1-month and 3-month follow-up with a single high intravenous dose (100–400 mg) of hydrocortisone given within 6 hours of trauma (Zohar et al., 2011).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) also have been proposed to prevent PTSD by virtue of their established efficacy for PTSD and their anti-anxiety affects. Shalev and colleagues (2012) tested the SSRI escitalopram versus placebo given over 8 weeks, initiated within 1 month post-trauma. There was no difference between escitalopram and placebo in PTSD rates. The study also randomized patients to exposure therapy and cognitive therapy, which were found similarly effective in preventing PTSD in initially symptomatic patients, and more effective than medication, suggesting that CBT approaches may be more effective for PTSD prevention than this class of medication.

In a medical record study, the use of morphine during early resuscitation and trauma care of 696 wounded soldiers in Iraq was significantly associated with a lower risk of PTSD (odds ratio 0.47; p <0.001) (Holbrook et al., 2010). The association continued to be significant after controlling for injury severity. The study was not randomized and was not designed to determine if the effect stemmed from pain reduction, antagonism of noradrenergic activity, or both. Another non-randomized study of trauma patients admitted to a hospital found that patients who met criteria for PTSD 3 months later received significantly less morphine at the time of hospitalization than those who did not develop PTSD (Bryant et al., 2009). The predictors of PTSD severity at 3 months were acute pain and mild traumatic brain injury after adjusting for injury severity, gender, age, and type of injury. The authors concluded that administration of morphine may attenuate fear conditioning. It is unclear whether morphine would be effective in the absence of physical injury and pain, although some animal data support attenuation of fear conditioning after a severe stressor (Szczytkowski-Thomson et al., 2013); additional randomized controlled trials are needed.

It should be noted that many patients receive benzodiazepines acutely, and there was early interest in benzodiazepines as an anxiolytic to prevent PTSD. Available data, however, suggest that benzodiazepines may impair extinction learning, lack efficacy for PTSD, and may even increase rates of PTSD when administered in the aftermath of trauma (Gelpin et al., 1996), leading the 2010 VA/DOD guidelines to list them as contraindicated.

Summary

PTSD may be preventable in patients at greatest risk—those with ASD or acute symptoms—who are given trauma-focused individual CBT, and one recent study suggests intervention starting within the first day post-trauma may be beneficial. It is less clear whether patients who are less symptomatic can have significant benefit from these types of early intervention strategies. Psychological debriefing is ineffective and possibly harmful; it is believed that required single-session debriefing with a review of trauma details is contraindicated and should be avoided. Although SSRI antidepressants have demonstrated efficacy for PTSD, a recent randomized controlled trial failed to show efficacy of escitalopram for PTSD prevention. The most promising pharmacotherapies with positive preliminary support are hydrocortisone and morphine given around the time of trauma, but large randomized clinical trials targeting individuals with a range of traumas, including trauma that does not include physical pain due to injury, are needed before definitive conclusions may be drawn.

The types of DOD suicide prevention interventions profiled here include crisis lines, gatekeeper training, primary care training and services, restricting access to lethal means, and a comprehensive suicide prevention program. When efficacy data are not available from DOD, the committee draws on efficacy data from similar programs in civilians. This section also describes a large-scale research effort that aims to inform ongoing health promotion, risk reduction, and suicide prevention efforts.

Suicide Crisis Lines

Each of the services prominently posts on its suicide prevention website the 800 number for the Military Crisis Line. Renamed the Military Crisis Line in 2012, the Veterans Suicide Crisis Line was launched in 2007 as a toll-free, confidential resource that links service members in crisis (or families and friends) to qualified responders. Two years after being launched, the Crisis Line added an anonymous online chat service and, in 2011, a text messaging service. The Military Crisis Line is a joint undertaking of DOD, VA, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The rationale for a suicide prevention crisis line is that suicide is often associated with stressful life events, and it is surrounded by psychological ambivalence; those surviving a suicide attempt often claim that their wish to die coexists with a wish to be rescued (Shaffer et al., 1988).

While the committee is aware of an National Institute of Mental Health–funded project to assess the feasibility of evaluating the Military Crisis Line (NIH RePORT, 2013), to date, the efficacy of the Military Crisis Line has not been evaluated. However, a descriptive study of the crisis call centers reported that the call volume to this national veterans crisis line, which is available 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, reached 171,000, with 70 percent of callers being male. It is worth noting that this service’s advertising has been targeted at overcoming stigma and the resistance among service members to seeking help, with slogans such as “It takes the courage and strength of a soldier to ask for help.” Over several years of implementation, the calls generated 16,000 referrals to care as well as referrals to services for homelessness and substance abuse (Knox et al., 2012).

The committee is aware of limited research in the biomedical literature that evaluate the efficacy of civilian crisis lines. Gould et al. (2007b) completed a study of 1,085 callers to a civilian hotline targeting suicidal adults in 2003–2004. This study assessed suicidality not only during the call, but also an average of 2 weeks afterward. It found that 50 percent of callers were indeed suicidal—they had a plan in place—and 8.1 percent had already taken some action to harm themselves immediately before calling the crisis line. The study also found a significant reduction, over the course of the call, in intent to die, hopelessness, and psychological pain. In the subsequent weeks hopelessness and psychological pain continued to decrease. The caller’s intent to die by the conclusion of the call was the strongest predictor of subsequent suicidality (i.e., suicidal thinking, plan, or attempt). The findings underestimated the effects of the hotline because they screened out callers whose suicide risk status was deemed by the counselor to be “too high,” according to their clinical criteria, to participate in the study. A subsequent study by the same team of investigators found that 50 percent of suicidal callers subsequently utilized psychological health referrals obtained by calling the crisis line (Gould et al., 2007a). A study of

a suicide prevention program for adolescents succeeded in reducing the suicidality of callers over the course of the consultation (King et al., 2003).

In a study of 14 call centers in the 1-800-SUICIDE network, Mishara et al. (2007) found great variability in adherence to protocol among volunteers receiving the calls. Most volunteers did not ask the most basic questions about suicidal ideation, such as how the caller intended to commit suicide or if the caller had the means to complete the suicide. Similarly, in 10 observed cases when a suicide appeared to be in process, the volunteer failed to follow protocol and send an ambulance to the caller’s location. The authors suggest establishing a routine monitoring system would help ensure that minimum standards are met by suicide call centers (Mishara et al., 2007).

Gatekeeper Training

Gatekeeper training is a generic approach that teaches specific groups of people to identify those around them who are at high risk for suicide and then to refer those people for treatment. The two most prominent gatekeeper training programs are sponsored by the Army: Ask, Care, Escort (ACE) and Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST). The former uses peers as gatekeepers, while the latter is generally reserved for health professionals, clergy, or officers.

The ACE program aims to use peers to target at-risk soldiers. Developed by the U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine, the program includes 1.5 hours of formal training with DVDs, PowerPoint files, handouts, and training tip cards. Its specific aims are to

• Train soldiers to recognize suicidality in fellow soldiers, including warning signs;

• Target soldiers who are reluctant to seek care because of stigma;

• Enhance the gatekeeper’s confidence to ask whether a peer is contemplating suicide;

• Train soldiers in active listening; and

• Encourage gatekeepers to take peers directly to the chain of command, a chaplain, or a behavioral health clinician (Ramchand et al., 2011).

The efficacy of the ACE program has not been evaluated, but according to a major review of DOD programs by the RAND Corporation (Ramchand et al., 2011), the program has been reviewed by a panel of three suicide prevention experts and “found to meet standards of accuracy, safety, and programmatic guidelines.”

The ASIST program for gatekeepers uses a 2-day training workshop. Its specific aims are to

• Identify soldiers who have suicidal ideation;

• Comprehend how gatekeepers’ beliefs and attitudes affect suicide intervention;

• Search for a shared understanding of reasons for suicidal ideation and reasons for living;

• Assess risk and develop a plan to increase safety from suicidal behavior for an agreed amount of time; and

• Follow up on safety commitments and ascertain whether additional help is needed (Ramchand et al., 2011).

The Army’s goal is to have at least two ASIST-trained gatekeepers for each installation, camp, state, territory, and reserve support center. The Army’s policy requires training for chaplains and their assistants, psychological health professionals, and Army Community Service staff members. ASIST was founded in 1983 by researchers at the University of Calgary and a decade later was taken over by the company LivingWorks Education. ASIST is being used by the U.S. Army, U.S. Air Force, Canadian armed forces, and many civilian agencies (U.S. Army, 2013c).

The efficacy of ASIST has not been investigated by the Army. The RAND study of military suicide prevention programs identified five evaluations of civilian ASIST programs, but only one was published in the peer-reviewed literature. It was a survey of gatekeeper-trained staff members of a two-site health care facility serving over 1 million residents in Ontario, Canada (McAuliffe and Perry, 2007). The survey, which was conducted before and 2 years after gatekeeper training, found an annual increase of 14 to 21 percent in identification of suicidal risk by patients in the emergency department. It also found a 14.5 percent reduction in the length of stay for admitted patients. Respondents’ knowledge of what steps to take after assessing suicide risk increased from 87 to 97 percent. The percentage of staff endorsing the statement “I am provided with adequate ongoing training in how to assess and respond to patients with suicide risk” increased from 30 to 80 percent. The survey was not designed to evaluate the program’s impact on suicide rates or suicidality.

A systematic review of seven other gatekeeper programs (not including ASIST) found that the programs produced a significant improvement in gatekeeper’s attitudes, skills, and general knowledge of suicide prevention (Isaac et al., 2009). One of the seven programs being reviewed was for the Department of Veterans Affairs. That review found significant improvement in counseling center clinical and administrative staff (n=602) in staff knowledge, self-efficacy, and three gatekeeper skills from pre- to post-training (Matthieu et al., 2008). None of the gatekeeper programs, whether military or civilian, has been evaluated for their impact on rates of suicidality or suicide.

Primary Care Training and Services

Although not expressly intended to prevent suicides, one widespread DOD program designed to encourage recognition and high-quality treatment of depression and PTSD in primary care (using existing evidence-based screens), RESPECT–Mil,3 does have ingredients of effective suicide prevention. That is because the program requires that soldiers who are identified as having depression or PTSD symptoms be screened for suicide risk. Primary care provider education is one of only two effective types of suicide prevention programs according to an influential review article (Mann et al., 2005). Primary care offers a valuable opportunity for suicide prevention because most suicidal patients have contact with their primary care providers in the months before their death (Andersen et al., 2000; Luoma et al., 2002) and because entering primary care is considered less stigmatizing than entering specialty care. No patient outcome data are available for the RESPECT–Mil program, but a research psychologist is working with the program to implement a continuous program evaluation effort (RAND Corporation, 2013). A

____________________

3 RESPECT–Mil stands for Re-Engineering Systems of Primary Care Treatment in the Military. The program trains primary care providers in detection and treatment of PTSD and depression, relies on a nurse facilitator to ensure continuity of care, and has a behavioral health specialist review each case and consult with the nurse facilitator. For details of the program and reporting of efficacy, see Engel et al. (2008).

2009 internal evaluation of the RESPECT–Mil program found that among a convenience sample of service members previously deployed, RESPECT–Mil appeared to detect depression and PTSD problems in up to 5 percent of returning service members who were not detected as having problems during their post-deployment health assessment screening,4 a population-based screening process performed immediately following return from deployment (Military Health System Clinical Quality Management, 2009b). Among a different sample of RESPECT–Mil participants, 43 percent of service members who screened positive for PTSD or depression or received a diagnosis for either condition contacted psychological health services within 30 days (Military Health System Clinical Quality Management, 2009a).

Two of the most prominent primary care programs for civilians give primary care providers depression education or extra support, or both. On the Swedish island of Gotland, a program in primary care education led to a reduction in the suicide rate (Rutz et al., 1989). In the United States, a program5 using a depression care manager in primary care to provide algorithmbased care and monitoring of symptoms, adverse effects of drugs, and adherence to treatment was associated in a randomized controlled trial with less depression, less suicidal ideation, and less mortality (Alexopoulos et al., 2009; Bruce et al., 2004; Gallo et al., 2013). All-cause mortality was studied because the sample size (20 primary care practices) was too small to have the power to detect changes in the suicide rate.

Restricting Access to Lethal Means

Research shows unequivocal evidence of an association between firearm possession and increased risk of suicide (Freeman et al., 2003). Guns are the primary method of suicide by service members and veterans; these groups are known to have high rates of gun ownership (Claassen and Knox, 2011). A recent population-based study of veterans found that they were twice as likely as non-veterans to die by suicide and 58 percent more likely than non-veterans to use firearms rather than other suicide methods to end their lives (Kaplan et al., 2007). According to the DOD Suicide Event Report program, of the 301 military members in all services who died by suicide in 2011, 172 (60 percent) used firearms to kill themselves. Of those who used firearms, 141 (82 percent) used non-military-issue firearms and only 31 (18 percent) used military-issue firearms (DCOE, 2012a). That underscores the importance of assessing and addressing the access to non-military-issue firearms as well as military-issue firearms by people who are at risk for suicide.

International experts who reviewed the literature on suicide prevention interventions concluded that the restriction of access to lethal means is one of the few suicide prevention policies with proven effectiveness (Mann et al., 2005). In the United States, legislation aimed at tightening handgun control in the general population has been shown to reduce suicide deaths by firearms among some subgroups (Loftin et al., 1991; Ludwig and Cook, 2000).

DOD gun-safety protocols for military-issue weapons exist, but the guidance on lethalmeans counseling and restricting gun access is vague. Current DOD policy does not have provisions for restricting access to privately owned firearms for those believed to be at risk for suicide. In fact, the fiscal year (FY) 2011 National Defense Authorization Act (PL 111-383, Section 1062) prohibits the Secretary of Defense from issuing any regulation or policy on legally

____________________

4 See Chapter 4 for a description of the post-deployment health assessment.

5 The PROSPECT trial (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial).

owned personal firearms or ammunition kept by troops or civilian employees off base as well as from collecting any information on their guns or ammunition.6 More recently, however, DOD military leaders have been quoted in the popular press as stating that they are considering a policy that “will allow separation of privately owned firearms from those believed to be at risk of suicide” (Jordan, 2012). After the Israeli military restricted access to military-issue firearms,7 the suicide rate among adolescents (defined as ages 18 to 21) declined by 40 percent (Lubin et al., 2010). The VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide (VA and DOD, 2013) advocates restriction of lethal means for the suicidal patient.

In a study of National Violent Death Reporting System data, Caetano et al. (2013) found that in the general population alcohol was present in between 23 percent and 47 percent of people who died by suicide, with the percentage varying by race/ethnicity. Among those of Asian/Pacific Islands ancestry, 23 percent had positive blood alcohol, compared with 26 percent of blacks, 33 percent of whites, 38 percent of Hispanics, and 47 percent of American Indians and Alaskan Natives. The authors reported that the percentage of suicides with positive blood alcohol was lower in veterans than in non-veterans, although they did not present that data (Caetano et al., 2013).

In a study for DOD, Luxton et al. (2012) found that among active-duty service members who died by suicide in 2011, 21.3 percent had positive blood alcohol, and 8.7 percent tested positive for drugs. Among active-duty service members who attempted suicide, 64 percent showed evidence of drug or alcohol use. Prescription drugs, largely antidepressants and antianxiety medications, were the most frequently misused psychotropic drugs among service members with known drug use who completed or attempted suicide (Luxton et al., 2012). Restriction of medications commonly used in suicide is an effective method of suicide prevention, according to the systematic review by Mann and colleagues (2005). The military does not have any specific policy on restrictions on prescription drug availability.

Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Program

Responding to a spike in its suicide rate, in 1997 the U.S. Air Force (USAF) leadership implemented a multifaceted suicide prevention program consisting of 11 initiatives (see Box 5-1) (Knox et al., 2003). The broad-based initiatives were aimed at removing the stigma of seeking psychological health care, enhancing understanding of psychological health, and changing policies and social norms to encourage psychological health care and help individuals avoid negative career consequences from seeking help. The innovators who developed the program described it as a shift from viewing suicide as a medical problem to viewing suicide as a community-wide problem. During the program’s first 5 years, investigators found a 33 percent reduction in the rate of suicide, from approximately 12.1 per 100,000 to 8.3 per 100,000. They also found reductions in severe and moderate family violence (54 percent and 30 percent, respectively) and decreased rates for accidental death and homicides. A second report published in 2010 indicated that the lower suicide rates had continued in the years following 2003, except for 2004 when the program was implemented less rigorously (Knox et al., 2003). This USAF

____________________

6 PL 111-383: 111th Congress, Jan. 7, 2011.

7 The study restricted access by preventing soldiers who were going home for the weekend from taking their military-issue firearms with them.

program stands out among all other military prevention efforts for its comprehensiveness and for its evidence-based approach to reducing the suicide rate.

BOX 5–1

Initiatives of USAF Suicide Prevention Program

1. Leadership participation in suicide prevention activities

2. Provision of suicide prevention education in all formal training

3. Education of commanders to encourage help-seeking by subordinates

4. Increasing preventive functions performed by mental health personnel

5. Annual suicide prevention training for all military and civilian employees

6. Changes in policies to ensure that individuals under investigation for legal problems are assessed for suicide potential

7. Trauma stress response teams established to respond to terrorist attacks, serious accidents, or suicide

8. Establishment of a seamless system of services and Community Action Information Board to achieve a synergistic impact on community problems and reduce risk of suicide

9. Increased confidentiality when seen by mental health providers

10. Use of the IDS (Integrated Delivery System) Consultation Assessment Tool to enable commanders to assess unit strength and areas of vulnerability

11. Reliance on Suicide Event Surveillance System that tracks suicide events and facilitates analysis of potential risk factors

SOURCE: Knox et al., 2003.

Army STARRS

Although it is not a program intervention per se, Army STARRS (Study To Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers) is a 5-year research study of risk and protective factors for suicide whose objective is to better understand psychological resilience, psychological health, and risk for self-harm among soldiers. Launched in 2009 through a partnership between the Army and the National Institute of Mental Health, Army STARRS supports an interdisciplinary team of investigators working on five separate study components: the Historical Administrative Data Study, New Soldier Study, All Army Study, Soldier Health Outcomes Study, and Special Studies (NIMH, 2013; U.S. Army, 2013a). Findings from these studies will be used to inform ongoing health promotion, risk reduction, and suicide prevention efforts.

Summary

DOD sponsors numerous types of suicide prevention programs, most of which vary by service (Ramchand et al., 2011). The USAF has the strongest program, and it is the only comprehensive program. Although it is commendable that DOD supports many programs, few have been evaluated. From the civilian literature it is clear that many programs being used by the military—involving gatekeepers, educational campaigns, and hotlines—have some limited evidence of effectiveness. The type of suicide prevention with the strongest evidence of effectiveness—restricting access to lethal means such as firearms and psychotropic medications—is not being undertaken by the military, in spite of the fact that firearms,

particularly non-military-issue firearms, are used in 60 percent of military suicide deaths and psychotropic medications are frequently used in suicide attempts. DOD is sponsoring a largescale research study to better understand psychological resilience, psychological health, and risk for self-harm among soldiers, which may further inform targets for future prevention efforts.

A 2013 IOM committee—the Committee on Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces—completed a comprehensive assessment of DOD policies and programs to prevent, identify, diagnose, and treat substance use disorders (SUDs) in active-duty service members, members of the National Guard and reserves, and military dependents. That committee’s report, Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces (IOM, 2013b), and other recent literature provide the basis for the following discussion of military policies, programs, and services for SUD prevention and the evidence base for SUD prevention interventions. Appendix G includes a full descriptive analysis of the SUD programs that committee reviewed. This section is organized by the types of DOD substance abuse prevention interventions profiled in that committee’s report—drug testing, community-level education and outreach, service member education and training, screening and brief intervention, environmental strategies—and discusses the available evidence for these interventions.

Drug Testing

DOD and branch-specific policy emphasize drug testing as a SUD prevention strategy. The Military and Civilian Drug Testing Program requires all active-duty members to undergo a urinalysis at least once per year to test for illicit drug use (DOD, 2012b). All urinalyses test for marijuana, cocaine, and amphetamines, but testing for other drugs (LSD, opiates, barbiturates, PCP) is not done uniformly (Miech et al., 2013). Under the current zero-tolerance policy, a positive urinalysis result leads to separation from service. In 2012 DOD expanded the urinalysis drug testing programs to screen for some of the most commonly abused prescription medications, such as hydrocodone and benzodiazepines. Service members who have approved prescriptions will not be subject to disciplinary action for using them within the prescribed dosages and times.

Until recently, none of the branches tested for alcohol. In February 2013 the Navy rolled out an alcohol breath-testing program. Random breath testing is being conducted aboard Navy ships, and positive tests may be used to identify individual who receive assistance through the drug and alcohol program advisor and the Navy Alcohol Abuse Prevention Program (U.S. Navy, 2013).

As a prevention strategy, drug testing has a presumed deterrent effect by increasing awareness of the consequences of testing positive for illicit drug use (i.e., separation from the military). There is no research, however, showing that drug testing is an effective prevention strategy for service members and their dependents. As argued in Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces (IOM, 2013b), reports that cite decreasing rates of illicit drug use as evidence of the effectiveness of drug testing (Bray and Hourani, 2007; Bray et al., 2010; Miech et al.,

2013) do not take into account causality, secular trends, or other factors that affect rates of illicit drug use.

However, results from a recent study suggest that stringent military drug policy and programs may lead to a lifelong reduction in illegal drug use. Using a life-course perspective, Miech and colleagues (2013) examined long-term trends in past-year hallucinogen use among veterans and non-veterans by analyzing self-reported data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health for 1985–2010. The results indicate that among a subgroup of respondents who reported a history of illegal drug use before the age of 18, the prevalence of hallucinogen use was lower among veterans than among non-veterans. The authors concluded that this finding suggests that the policies had their greatest effect by altering substance use trajectories that had already started.

Community-Level Education and Outreach

Aside from drug testing, DOD relies heavily on campaign-style prevention programs, including That Guy and the national Red Ribbon campaign. The That Guy campaign uses online and offline public service announcements, a website with animated risk scenarios and modeling of prevention techniques, and prevention marketing. The overall aims are to increase awareness about the hazards of excessive drinking and to change attitudes about this behavior. Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces (IOM, 2013b) reviewed the campaign and found that it uses evidence-based practices of modeling, rehearsal, discussion, and practice and focuses primarily on negative perceived consequences, negative social consequences, and peer pressure. The committee is not aware, however, of any evaluation of the That Guy campaign.

Red Ribbon Week is an annual campaign conducted every October on military bases and in communities nationwide to raise awareness about SUD prevention and risk factors (National Family Partnership, 2013). The program is a universal prevention campaign aimed at addressing peer pressure and prosocial bonding in youth, as well as parent monitoring. In its review of the program, IOM (2013b) found no published information on Red Ribbon’s theoretical basis and concluded that the program varies in campaign implementation across branches and bases and suffers from a lack of specification of participation requirements.

IOM (2013b) could not determine whether the That Guy or Red Ribbon programs are effective at preventing risky drinking and alcohol misuse among service members. There are at present no published peer-reviewed studies on formal outcome evaluations of these campaigns. Research on media campaigns to prevent drug use in youth has found that theory-based and evidence-based media campaigns can be effective in that population (Crano and Burgoon, 2002). However, the effectiveness of campaign activities within the military is unknown.

There are several notable population-based and community outreach initiatives sponsored by the Air Force. The Culture of Responsible Choices (CoRC) is a commander’s program with emphasis on leadership and individual-, base-, and community-level involvement—underscoring responsible behaviors, including avoiding alcohol and drug abuse; the prevention of accidents; tobacco cessation; decreasing obesity and increasing fitness, health, and wellness; prevention of sexually transmitted diseases; and so on. The program includes annual training of leadership (i.e., commanders and health care providers) in prevention programs. Program implementation targets, in order, service members and their families, military bases, and, finally, surrounding communities. It specifies a clear chain of command regarding leadership, training, responsibility

for implementation, and dissemination from the base to the surrounding community. Although there are no published studies on the efficacy of CoRC, the IOM (2013b) concluded that CoRC provides a good model for standardizing prevention training and delivery across the military branches and that it should be evaluated to determine its efficacy.

The New Orientation to Reduce Threats to Health from Secretive Problems That Affect Readiness (NORTH STAR) program is a community-based framework for the prevention of substance problems, family maltreatment, and suicide. It is an integrated delivery system involving commanders and providers partnered with Air Force community action and information boards at each of the 10 major commands (Heyman et al., 2011). The partners at each command selected the programs that matched their specific risk and protective factor profiles using a guide on evidence-based programs that called for rating the programs according to evaluation outcomes and targeted risk and protective factors. The guide also includes training, implementation, and survey evaluation protocols. The use of a framework, delivery system, and guide to select prevention programs that fit a particular base’s risk and protective factor profile is based on extensive community-based prevention research strategies that have been evaluated in civilian populations (Heyman and Smith Slep, 2001; Pentz, 2003; Riggs et al., 2009). Studies of the effectiveness of the NORTH STAR program indicate that the program is promising. A randomized controlled trial of the program involving 24 Air Force bases and more than 50,000 active-duty military members found reductions in alcohol abuse and prescription drug use (as well as suicidality and partner physical abuse), after controlling for the level of integrated delivery system functioning and command support (Heyman et al., 2011).

In addition to the CoRC and NORTH STAR programs, Enforcing Underage Drinking Laws (EUDL) is another promising Air Force program. EUDL is a pilot program designed to reduce drinking and associated alcohol-related misconduct among underage active-duty Air Force members. The program funds the development of broad-based community coalitions to implement environmental prevention strategies that reduce the availability and consumption of alcoholic beverages by underage service members. The strategies employed include (1) enforcement aimed at reducing the social availability of alcohol, (2) compliance checks at alcohol establishments, (3) driving-under-the-influence checks, (4) education of state legislatures and development of local policies, (5) a media awareness campaign, and (6) provision of alternative activities to alcohol use. (See the section about environmental strategies below for more information about this type of SUD prevention.) Evaluation results from the five sites showed significant reductions in arrest rates for minors in possession of alcohol and for driving under the influence, both within sites and compared with control communities (Spera et al., 2010, 2012). Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces (IOM, 2013b) reported that there are currently no plans to expand it to all Air Force bases; however, some of its components will be implemented within other Air Force–wide initiatives.

Service Member Education and Training

DOD-wide policies (DODD 1010.1 and DODD 1010.4) call for the provision of education to ensure that personnel understand the implications of not adhering to DOD policies concerning the use of alcohol and other drugs. However, the policies provide little or no guidance for prevention strategies involving large-scale efforts to educate individuals on the risks and health consequences of the use of alcohol and other drugs.

Each service has specific policies for providing education and training. Alcohol and other drug abuse prevention curricula are included in the general military training provided by the services. The nature of the information and the frequency with which it is provided vary by service, but generally training entails providing service members with information about substance use policies, responsible behavior, risks and consequences of use, and available SUD programs and services.