INTRODUCTION

The changing international security environment since the end of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union has created incentives to revisit with new approaches, methods, and tools the Cold War doctrine of strategic deterrence as the cornerstone of U.S. national security strategy. The principal change that has prompted a reassessment is the transformation of the international system from a bipolar world in which the Soviet Union posed the only major threat of an armed attack on the United States with nuclear weapons to a world of multiple potential adversaries with different cultures and decision-making processes and armed with nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

Does this more complex strategic environment demand a more complex strategy of nuclear deterrence for the Air Force, the Department of Defense (DoD) and the other elements of the U.S. national security community (Morgan, 2003)? A comprehensive answer to this question appeared in a review of U.S. deterrence strategy by DoD in 2006, summarized as follows by Bunn (2007, p. 1):

In its 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) Report, the Bush administration set forth a vision for tailored deterrence, continuing a shift from a one-size-fits-all notion of deterrence toward more adaptable approaches suitable for advanced military competitors, regional

weapons of mass destruction (WMD) states, as well as non-state terrorist networks, while assuring allies and dissuading potential competitors.1

Bunn (p. 1) pointed out that this official U.S. document was the one in which the term tailored deterrence first appeared but without explaining what it means in detail or how this strategy might be carried out. However, 7 years later it is the term of art to describe the joint strategy of deterrence pursued by the United States and South Korea in dealing with the threat posed by North Korea (Parish, 2013) and has become the focus of increased attention in the academy and by analysts in the policy community (Post, 2012; Schneider and Ellis, 2012; Lowther, 2013a).

Bunn (2007) identified three aspects of any deterrence strategy and specifically highlighted a fourth aspect in a tailored deterrence strategy. Any deterrence strategy has a focus on (1) the adversary’s action to be deterred, (2) the agent’s military capabilities necessary to deter the action, and (3) the communications capabilities necessary to provide the adversary with information about the action to be deterred and the agent’s military capabilities. A tailored deterrence strategy highlights specifically the situation-specific knowledge and actor-specific knowledge required to communicate this information to the adversary and thereby deter the action.

In Bunn’s words (p. 1), “Deterrence aims to prevent a hostile action (for example, aggression or WMD use) by ensuring that, in the mind of a potential adversary, the risks of action outweigh the benefits, while taking into account the consequences of inaction.” This statement is not the whole story, since adversaries do not always do a rational cost-benefit calculation and act accordingly. Further, success in deterrence often depends on a broader set of influences, such as the organizational and societal characteristics of the deteree, as described below.

To take account of these complexities, a tailored deterrence strategy in the current strategic environment requires actor-specific knowledge about a variety of actual and potential adversaries whose culture and cost/benefit calculus may differ, depending on the type of decision unit (predominant leader, single group, or a coalition of multiple autonomous actors) that defines the governmental decision units of different adversaries and the cultures of the societies in which these governments are located (Allison, 1969; Hermann and Hermann, 1989; Post, 2012).

Tailoring deterrence and assurance strategies calls as well for situation-specific knowledge. The external position of the adversary or ally in the regional or global strategic environment needs to be taken into account to implement a tailored strategy of deterrence or assurance. Are the adversaries and allies peers and near-peers, regional actors, or non-state actors? Do they have weapons of mass destruction and the means to use them (Bunn, 2007; Schneider and Ellis, 2012)? Is the occasion

________________

1 Bunn’s summary is taken from Department of Defense (2006, p 2). She notes additional discussion of tailored deterrence in this document is on pages 4, 27, and 50-51.

for making decisions a general deterrence or assurance situation; an immediate deterrence or assurance situation; or an extended deterrence or assurance situation (Morgan, 1983, 2003)? Also, is it a crisis or noncrisis situation in which the task is to establish credibility and dissuade adversaries or allies from escalating a conflict (Hermann, 1969; Brecher and Wilkenfeld, 2000)? Is it a potential proliferation situation in which the arms control task is to strengthen trust and dissuade allies or adversaries from taking independent action to acquire or increase their nuclear capabilities (Morgan, 2003; Bunn, 2007)?

In summary, tailoring a strategy must account for myriad details, ranging from the objective and emotional stakes of affected parties, internal domestic politics in all of the parties involved, to the operational military capabilities of all parties. What follows draws on political science research in the area of comparative foreign policy analysis to highlight and integrate these considerations that operate at different levels of analysis. The goal is to provide a clear and concise analytical framework for identifying how adversaries and allies see and think about the strategic environment, in order to reduce uncertainty and anticipate their responses to U.S. deterrence and assurance decisions. The analytical framework focuses specifically on the “human factors” involved in deterrence and assurance decisions, which need to be factored into the deployment and use of weapons and delivery systems in the complex strategic environment of the 21st century.

TAILORED DETERRENCE AND ASSURANCE: THE ANALYSIS OF HUMAN FACTORS

Kenneth Waltz (1959) has identified three main levels of analysis, which identify the locations of different causal mechanisms for the analysis of decisions to deter or assure and their consequences. Psychological mechanisms such as belief systems, motivational biases, and personality traits are located at the individual level of human nature. Social mechanisms, such as the type of government or economy, are domestic-level mechanisms at the level of society, while systemic mechanisms, such as the distributions of economic and military power among states, are located at the external level of the international system. In this appendix, the focus is primarily on social mechanisms and external situations that define situation-specific knowledge, while Appendix E will focus on the psychological mechanisms and internal dispositions of decision units that specify actor-specific knowledge.

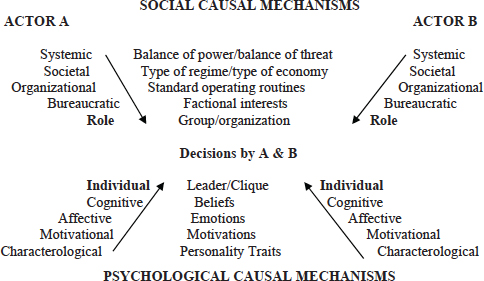

In the top half of Figure D-1 the social psychology of mechanisms located at the external systemic, societal, organizational, and bureaucratic levels of analysis is characterized by roles (in bold) for Actor A and Actor B in which decision units are composed of individuals playing roles within a decision unit and in the larger strategic environment. In the bottom half of Figure D-1 the individual psychol-

FIGURE D-1 Decision units and the funnels of social and psychological causality. SOURCE: Adapted from Campbell, et al. (1960); Waltz (1959); Allison (1969); Kegley and Witkopf (1982); Post (2003).

ogy of mechanisms located within each individual (in bold) are the processes that generate thoughts, feelings, and motives regarding the enactment of their roles in the strategic environment, which are the focus Appendix E. As one moves up the levels of analysis from the individual through the bureaucratic and organizational levels of the state and the society to the regional or global system, the locations of the causal mechanisms become more remote from the decision unit as the site of the decisions by Actor A to deter or assure and the decisions by Actor B to respond. However, they may still act to constrain the range of choices and perhaps even influence the actual choice of action.

Collectively, these mechanisms act as a funnel of causal forces and conditions that interact with mechanisms of the decision units to produce decisions by two actors (A and B), as shown in Figure D-1 (Campbell et al., 1960; Kegley and Witkopf, 1982). The relative influence of each level of social and psychological mechanisms is likely to vary by the type of decision-making situation. The remote social mechanisms may influence strategic decisions of general deterrence and assurance, which involve weapons procurement, development, and deployment and require more resources, time, and planning to implement (Trexel, 2013). The proximate psychological mechanisms may be more influential in crisis decision-

making situations when stress from the situational features of surprise, high stakes, and short response time can influence immediate and extended deterrence and assurance decisions (Brecher and Wilkenfeld, 2000).

Graham Allison (1969) has identified three models of the social mechanisms in the upper half of Figure D-1, differentiated by distinct decision-making processes: rational choice processes at the external and societal levels (Model I), standard operating procedures at the organizational level (Model II), and bargaining processes at the bureaucratic level (Model III). Depending on which of these mechanisms dominates the decision-making process, the decision to deter or assure by Actor A and the decision to respond by Actor B may be the products of the processes of deliberation and choice associated with Model I; the organizational routines associated with Model II; or the consensus-building processes associated with Model III (Allison and Zelikow, 1999).

Post (2012) has suggested an additional decision-making model (Model IV) of the psychological mechanisms in the lower half of Figure D-1, which specifies a predominant leader’s character, combinations of personality traits, and cognitive, affective, and motivational processes as important causal mechanisms. If an individual occupies a role in a decision unit where the individual’s actions are indispensable in producing the decision, and if the decision maker’s choice of action is idiosyncratic— that is, other individuals placed in the same strategic location would choose a different action then the individual’s psychological decision-making mechanisms may be more powerful than the social mechanisms located in more remote sites in the funnel of causality (Greenstein, 1987).

To illustrate Model IV, consider the analysis by Sherman Kent, the founding father of the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA’s) Office of National Intelligence Estimates, who was tasked with understanding the reasons for the intelligence failure during the Cuban missile crisis to understand until too late that the Soviet Union was installing offensive missiles in Cuba. The U.S. government had found it difficult to believe that rational adversaries could take such a risky step. Kent concluded that insufficient attention had been paid to the personalities and political behavior of two key adversaries, Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro. While they were not “irrational,” they were both adventurous leaders with high risk-taking propensities, which were personality traits that were not given sufficient weight in understanding their likely behavior and the decision to install Soviet missiles in Cuba (Post, 2012).

The simplest kind of decision unit that meets the conditions of action and actor indispensability is the predominant leader decision unit, in which the power to decide rests in the hands of a single leader, such as Saddam Hussein in Iraq or Muammar al-Gaddafi in Libya and the Great Leader, Dear Leader, or Great Successor (Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il, or Kim Jong Un) in North Korea. External events and actions by others may also empower individuals: In crisis situations, for example,

decision making may gravitate into the hands of a leader or a small, ad hoc group, which may become indispensable in making decisions insulated from the organizational and bureaucratic constraints associated with noncrisis decisions (Hermann, 1969, 1972; Brecher and Wilkenfeld, 2000; Allison and Zelikow, 1999; Schafer and Crichlow, 2010).2 It is useful, therefore, to distinguish among both the different kinds of decision units and the situations in which they operate as decision units.

Studies of leaders, single groups, and multiple autonomous actors have revealed a common thread connecting their decision-making processes, which scholars have identified with different labels that tap the same variable namely, whether these different decision units are “open” or “closed” with respect to the external strategic environment (Rokeach, 1960; Rosenau, 1966; Kowert, 2002; Hermann and Hermann, 1989). Analyses of leader personalities identify open and closed minded individuals as extroverts or introverts (Rokeach, 1960; Etheredge, 1978; Kowert and Hermann, 1997; Kruglanski, 2004). Other analyses distinguish open and closed leader/advisor systems (Kowert, 2002; Hermann and Preston, 1994; Schafer and Crichlow, 2010; Hermann, 2003).

Analyses of different societies contrast open and closed regimes and economies as outward-looking or inward-looking (Rosenau, 1966; Solingen, 1998, 2007; Schaub, 2013). Analyses of international conflict and cooperation identify periods of relative inattention or attention in the relations between strategic dyads in the regional and global international systems (Deutsch, 1954; Deutsch and Singer, 1964; Waltz, 1959, 1964; Cobb and Elder, 1970; Solingen, 2007; Rasler et al., 2013). All of these studies focus at external systemic, societal, or state levels of analysis on whether the causal mechanisms in the decision unit (predominant leader, single group, multiple autonomous actors, or the state) operate to make it relatively “self-contained” or “externally influenceable” (Hermann and Hermann, 1989; see also Rosenau, 1966, and Solingen, 2007).

In a given crisis or conflict any one or a combination of the four models discussed earlier, Allison’s Models I, II, III or Post’s Model IV, may shed light on the manner in which decisions to escalate or de-escalate are made and expected. In addition, in acute international crises characterized by the elements of surprise, high stakes, and short time for decisions, it is likely that Post’s Model IV will be all the more important to explain how decisions are skewed by personality traits, group dynamics, and fuzzy thinking caused by fatigue and acute stress. Crises such as the Cuban missile crisis are characterized by a threat to major values, ambiguous

________________

2 Not all predominant decision units are in autocratic regimes. Some democratic regimes assign this power to a leader on some issues, but the U.S. president has the decision-making authority to use U.S. nuclear weapons but shares power with others (in this case, Congress) on other nuclear decisions, such as acquisition of nuclear weapons.

or incomplete information, short time for decisions, and surprise (see Hermann, 1969, 1972; Brecher and Wilkenfeld, 2000).

Unfortunately, at such times when the smartest decisions need to be made, it is also the most difficult from a psychological standpoint. Crisis stress and fatigue may lead to emotionally distorted decisions. Such decisions under high anxiety are more likely to reflect groupthink, ethnocentric (or we-they) thinking, oversimplification, stereotyping, and premature conclusions before all the facts are considered. High stress can also cause a tendency in some leaders to freeze and become ineffective. Others indulge in mirror imaging and selective perception. Crisis decisions are also often made in small, ad hoc, face-to-face groups that can be influenced by group dynamics and a tendency to exhibit a risky shift phenomenon and conformity to group perspectives (groupthink) as well as decision momentum (Jervis, 1976; ‘t Hart et al., 1997; Schafer and Crichlow, 2010).

INTEGRATING HUMAN FACTORS IN DETERRENCE AND ASSURANCE DECISIONS

It is helpful in diagnosing and prescribing deterrence and assurance strategies and tactics to focus the attention of decision makers on those specific conditions that enhance the effectiveness of deterrence and assurance strategies rather than the conditions that make it more difficult to deter adversaries and assure allies. In order for a deterrence or an assurance message to be effective, it is necessary that the target of the message be receptive to it. Two general conditions of receptivity are that the recipient must be both willing and able to receive the message. If these conditions are weak or nonexistent, then the sender of the message will have to develop strategies to overcome these deficits or somehow work around them in order to deter or assure the recipient.

An effective strategy of tailored deterrence or assurance is designed to meet these two conditions. The first step in tailoring a deterrence or assurance message is to diagnose the situation-specific and actor-specific features of the strategic environment and decision unit, respectively, which indicate whether the relevant systems of interest are “open” (receptive) or “closed” (unreceptive) to the message being sent. The second step is to ask and assess whether or not these conditions effectively block the message. Depending on the answer to this question, the third step is either to send the message “as is” or devise a “work-around” strategy to overcome or otherwise neutralize the blocking conditions in order to communicate the tailored message. If it proves impossible or too costly to do so, then decision units should probably consider another means than deterrence or assurance and/or change their own goals in dealing with the adversary or ally.

It is also important to understand that the same conditions apply in effectively diagnosing and prescribing both deterrence and assurance decisions. The same

decision may have both deterrence effects on adversaries and assurance effects on allies. The interdependence of these decisions has long been recognized by deterrence theorists in extended deterrence situations (Schelling, 1960, 1966; Jervis and Snyder, 1991; Khong, 1992). The most famous historical example of this analytical linkage is articulated by the Domino Theory, coined initially in the Eisenhower administration regarding the threat to the security of SEATO members posed by a communist seizure of power in Vietnam. This move would pose a geographical threat of communist invasion into neighboring states, such as Laos and Cambodia, which would fall like a row of dominos (Wolf, 1967). It also raises the issue of the credibility of U.S. commitments to deter and defend threats to other U.S. allies outside Southeast Asia during the Cold War (Schelling, 1966). These examples underline the interdependence of credible deterrence and assurance commitments: Deterring an adversary assures an ally, and vice versa, assuring an ally deters an adversary (Schelling, 1966).

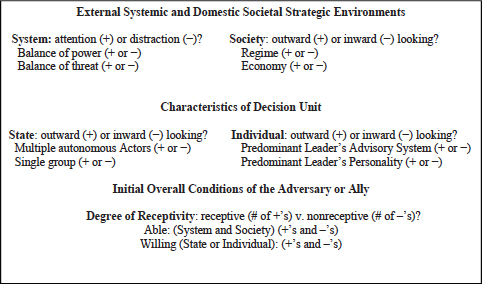

An initial estimate of the degree of difficulty either in deterring an adversary or assuring an ally is a function of the answers to the questions posed in Figure D-2 about the targets of deterrence or assurance. The menu in Figure D-2 is a helpful tool as a decision-making heuristic or checklist in integrating the causal mechanisms to obtain a cross-level understanding of the likely degree of receptivity by the adversary or ally to deterrence or assurance decisions.

FIGURE D-2 Decision-making heuristics for deterrence and assurance decisions. NOTE: Open (+); closed (–). SOURCE: Waltz (1959); Hermann and Hermann (1989); Solingen (1998, 2007).

The mechanisms in the menu can each take two values: plus (+) or minus (−), which represent the binary states of “open” or “closed” for each mechanism. The binary values for each mechanism on the menu act as logic gates for assessing the likely response of the adversary or ally to the U.S. stimulus. The menu identifies potential necessary and sufficient conditions for the stimulus to elicit the desired response under the macrolevel conditions of human nature, domestic society, and the international system that either reenforce or mitigate the effects of the stimulus (Waltz, 1959). The state’s organizational and bureaucratic mechanisms supplement the view of those macrolevel processes with a view inside the state of microlevel processes at the organizational, group and individual levels of analysis (Hermann and Hermann, 1989; Hermann, 2003; Post, 2003, 2012).

If the two initial logic gates of external system and society in the strategic environment are open (+), then the background conditions of the target are receptive to a deterrence or assurance message from the sender. These initial conditions at the external and domestic levels of analysis permit the target to receive a message from the sender. If one of the logic gates is open while the other is closed, then a deterrence or assurance message should be tailored toward the open gate. Depending on which gate is open, the message should be a military or an economic threat or promise. If both gates are closed, then it is relatively unlikely that the exercise of hard power based on military or economic resources will be effective, and the exercise of soft power through other means may be needed—for example, appeals to core norms of the target through diplomatic or cultural channels of communication (Nye, 1990, 2011).

The next level of analysis in Figure D-2 is the internal characteristics of the decision unit (multiple autonomous actors, single group, predominant leader and advisory system). It is possible for all three types of decision units to be present in a given society and accessible to messages from the sender (Rosati, 1981). It is also possible for decision makers at one of these levels of analysis to be receptive to a deterrence or assurance message even if the external conditions in the strategic environment are not receptive. The center of decision-making gravity may reside in one of them or be arranged in a hierarchical or a segmented configuration. It is possible as well for different decision units to be associated with different issues or situations.3 Ideally, a deterrence or assurance message is targeted at a decision unit that is in the open condition and has the power to respond to the message.

________________

3 For example, in the U.S. case the separation of powers among executive, legislative, and judicial branches along with a bureaucratized executive branch may make the decision-making process more complex in some situations and more centralized in other situations (Hermann, 1969; Walker and Watson, 1992). In the U.S. case the power to make foreign policy decisions resides in both the White House and the Congress for some issues and situations while in others the White House has the power to make decisions.

The “ultimate decision units” (Hermann and Hermann, 1989) in any state are individuals who may decide alone or with others to respond authoritatively to a deterrence or assurance message.4 It may be the case that a heterodox pattern of open and closed conditions exists inside the state at the levels of different decision units. Some individuals may be receptive to the message while others are not, which makes the exercise of deterrence and assurance power a relatively uncertain enterprise. In the end, it depends on (1) whether the external environmental situation permits a decision maker to be receptive, (2) the condition of the decision unit in which an individual or group resides is in a receptive condition, and (3) whether an individual is also psychologically in a receptive condition.

In particular, the relevant indices from content analysis techniques employed to study predominant leaders may also be useful for studying single groups and multiple autonomous actors as decision units. They may indicate whether these aggregate decision units as well as predominant leaders are in an open or closed condition. Generally, open decision units are more slow and deliberate while closed decision units are relatively fast and frugal in making decisions. Some configurations of decision units and situations can produce interaction effects leading to different types of risky decisions defined as extreme (risk-acceptant) rather than moderate (risk-averse) decisions (Hermann and Hermann, 1989). These possibilities are tabulated in Table D-1 for the four types of decision units.

The relevant indicators of open or closed conditions for predominant leaders are high or low integrative complexity; moderate or extreme needs for power, affiliation, and achievement; symmetrical or asymmetrical beliefs about the control of historical development by self and other; and non-zero-sum or zero-sum subjective games for self and other.5 The analysis in Appendix E of these psychological

________________

4 Hermann and Hermann (1989, p. 363, n.1) define an ultimate decision unit this way: “If there is a decision, it is made by an individual, group of individuals, or multiple actors who have both (a) the ability to commit or withhold the resources of the government in foreign affairs and (b) the power or authority to prevent other entities within the government from overtly reversing their position without significant costs (costs which these other entities are normally unwilling to pay). We refer to the decision unit that has these two characteristics for a given issue at a particular time as the ‘ultimate decision unit’.”

5 Some of these indicators also interact with other personality traits to generate open or closed conditions: low need for power in combination with a low belief in historical control produces respect for external constraints, awhile a high need for power in combination with either a low or high belief in historical control produces challenges to external constraints. Different combinations of conceptual complexity and self-confidence interact to cause variations in openness to information (Hermann, 2003, pp. 188-195). Different combinations of power, affiliation, and achievement motivations are indicators of a decision unit’s risk-averse or risk-acceptant orientations, as are different combinations of the instrumental operational code beliefs I-3, I-4a, and I-4b (Winter 2003; see also Walker et al., 2003). These indicators are discussed and illustrated in Appendix E.

TABLE D-1 Risk Propensity of Different Decision Units in Different States

| Decision Unit | Internal States | Open/Closed System | Risk Propensity |

| Predominant leader | Contextual sensitivity | Insensitive (c) | Extreme Moderate |

| Sensitive (o) | |||

| Single group | Degree of consensus | Agreement (c) | Extreme Moderate |

| Disagreement (o) | |||

| Multiple autonomous actors | Relations among actors | Zero-sum (c) | Extreme Moderate |

| Non-zero-sum (o) | |||

NOTE: Open (o); closed (c).

SOURCE: Adapted from Table 1 in Hermann and Hermann (1989).

mechanisms concludes that these indicators are also likely to be valid for assessing the open or closed conditions of single groups and multiple autonomous actors.

In each instance and at each level within a decision unit, the key questions regarding receptivity are whether the conditions of opportunity (is the decision unit able?) and willingness (is the decision maker willing?) are present (Most and Starr, 1989). It is possible for the environment at each level to permit a response; however, the decision maker(s) may be unaware and/or unwilling (Sprout and Sprout, 1956; Kupchan, 1994; Walker, 2013). These uncertainties pose dilemmas in the form of crises of observation for the sender of the deterrence or assurance message. To whom should the message go and how should it be tailored?

A strategy of deterrence or assurance in this context refers to sending a message that recognizes the constraints and incentives in the recipient’s strategic environment at the systemic and societal levels of analysis while navigating the organizational and bureaucratic constraints and opportunities inside the recipient’s decision units. The response by a decision unit in the open condition is normally not an extreme decision that radically escalates or deescalates from the status quo. It is instead a pattern of decision making that is risk-averse rather than risk-acceptant and, therefore, is likely to be an incremental rather than a radical departure from the status quo (Braybrooke and Lindblom, 1963; Hermann and Hermann, 1989; see also Walker and Malici, 2011; Tuchman, 1984; Neustadt and May, 1986).

In the open condition a response is based primarily on information about the strategic environment and the sender’s message rather than on structural biases and social mechanisms inside multiple autonomous actors or single groups as the decision units or unconscious psychological mechanisms in the decision-making processes of predominant leaders as the decision unit. Departures from the status quo are governed by the amount of information available to the decision maker; the less information available, the bigger is the uncertainty about the consequences of actions and the smaller is the opportunity and willingness to initiate bigger

changes from the status quo. Conversely, the more information available, the bigger is the possible change because of the increase in certainty in a high-information environment about the consequences of various courses of action.

Since decision units normally operate in a complex environment with a relatively low information-processing capacity, they should be risk-averse and make moderate decisions. However, if decision units are closed and do not recognize the conditions of environmental complexity and low information due to the operation of psychological or social mechanisms, then they are prone to being risk-acceptant and making extreme rather than moderate decisions (Braybrooke and Lindblom, 1963; Hermann and Hermann, 1989; Walker and Malici, 2011).

TOOLS FOR MAKING TAILORED DECISIONS TO DETER AND ASSURE

There are four central research questions about deterrence and assurance strategies: (1) What deters and assures? (2) What military capabilities and optimal force postures are needed to provide deterrence and assurance effects? (3) What are the communications capabilities required to send effective deterrence and assurance messages? (4) What situation-specific and actor-specific knowledge is desirable to tailor effective deterrence and assurance messages? These four questions correspond to the three aspects of any deterrence or assurance strategy and the importance, identified by Bunn (2007), of tailoring the strategy.

In addressing these four questions it is important to recognize that the answers are interrelated. The answer to what deters or assures is that military capabilities can help deter and assure; however, they are neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for deterrence success. As discussed in Chapter 2, a variety of influences may be necessary (diplomatic and economic among them), and, in some cases, deterrent efforts will fail even when the would-be deterer believes they should succeed. Another factor in success is the communications capabilities available to convince both adversaries and allies that military capabilities (and other aspects of influence) are available and ready for use against an adversary and on behalf of an ally.

The possibility of strategic deception in the form of convincing allies and adversaries that one has more military capabilities than is actually the case underlines the psychological character of deterrence or assurance success. A strategic surprise, such as the U.S. discovery after the invasion of Iraq in 2003 that Saddam Hussein did not have nuclear weapons, is always possible. Conversely, deterrence failure may occur even though the distribution of military capabilities may be asymmetrical in favor of the deterring power, because the putative deteree does not believe this information. In turn, the effective communication of military capabilities and the resolve to use them depends on the application of local knowledge of the situation and actors in question. However, admitting these strategic possibilities does not negate the central importance of military capabilities (actual or perceived) in tak-

ing credible deterrence or assurance actions, even if deterrence failure occurs due to domestic imperatives to attack anyway or doubts about the deterring power’s credibility.

What Military Capabilities Deter and Assure?

Specifically, what are the optimal nuclear and conventional force postures for carrying out deterrence and assurance, including toward non-state actors as well as peers or near-peers and regional state actors? Schneider and Ellis identify seven classic elements of the U.S. deterrence strategy directed toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War:

• Having retaliatory forces capable of inflicting a level of damage considered unacceptable to the Soviet leadership,

• Possessing a second strike capability that could survive a surprise attack,

• Having a will to use this nuclear force in a confrontation if necessary,

• Communicating that the United States had both the will and the capability described so the U.S. threat was credible.

• Having an intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance system able to identify the origins of any attack, thereby answering the “who did it?” question,

• Having the capability to identify and strike a target set of the highest value to the Soviet Union and its leaders,

• Having a rational adversary leadership who preferred to live and stay in power rather than die in order to inflict destruction on the United States (Schneider and Ellis, 2012, pp. 462-463).

With the end of the Cold War and the emergence of multiple new nuclear powers led by decision makers with different cultures, personalities, historical experiences, and military capabilities, this Cold War deterrence strategy may not be optimal for all possible rivals, especially those far different from the Soviet Union, including some non-state actors (Lowther, 2013b; Trexel, 2013).

In particular, non-state actors like al-Qaeda may be significantly more difficult to deter than state actors since the former may have no known return address. Some of their followers may also be willing to martyr themselves in order to strike a blow against the far enemy—that is, the United States. A policy of deterrence by denial may be the most effective means of deterring a non-state actor’s use of WMD. By keeping chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons out of the hands of such radical groups, they will be unable to strike a WMD blow.

Thus, it is desirable to deter such groups from acquiring WMD capabilities by adopting security measures to lock down so-called loose nuclear material, to make it more difficult to smuggle materials out of nuclear facilities worldwide, to increase

surveillance of threatening groups, to take offensive actions against terrorist rings, and to provide a layered defense in depth against the transfer of WMD materials, WMDs, and persons of concern into the continental United States and allied territories. By making it more difficult to acquire WMD materials, to acquire the ability to transport and manufacture weapons from it, and to transport such arms and penetrate to significant targets, the U.S. can deny terrorists and other non-state foes the ability to destroy targets with such weapons.6

The Use of Game Theory

What if these kinds of efforts fail and nuclear proliferation occurs so that peers or near-peers, regional powers, and non-state actors acquire nuclear weapons? Game theory has long been a traditional tool for answering this question about capabilities along with operations research and systems analysis (Schelling, 1960; Ellsberg, 1961). Together with gaming possible scenarios in man/machine simulations, the representation of the logic of maximizing benefits and minimizing costs in strategic interactions with game theory is still a desirable research strategy for investigating the logic of deterrence and assurance against peers and near-peers, regional actors, and non-state actors in the 21st century security environment.

The 2 × 2 ordinal game (two players with two choices) is a mature tool in the repertoire of rational choice theories of decision making, including decisions for war or peace. It focuses on the deliberations and decisions of two rational players who realize that the outcomes of their decisions depend significantly on each other’s choices and capabilities. Classical game theory models of this kind assume that both players make their choices based on the condition of two-sided information, i.e., that each knows the capabilities and preference rankings of both self and other for the four different outcomes generated by the intersection of their respective choices. With this information each player can calculate the optimum

________________

6 There are about 20 steps a non-state group would have to take to get and use a nuclear weapon in the United States. Such a group would have to acquire WMD material and then transport it outside of the state where it was stolen. Then the group would have to manufacture such an explosive and transport it to the United States passing through several layers of defenses designed to detect and intercept it. Finally they would have to successfully transport the finished nuclear weapon to the target area and employ it against a continental U.S. target. If the probability of each such step is assumed to be independent of the others in the process and if each step is reduced to just a 50 percent probability of success by taking defensive measures at each point in the 20-step process, then the chance of a successful terrorist nuclear attack would be reduced to less of than one in a million. If each step is assumed to be necessary, then failure at any one of the 20 steps could prevent the attack by itself. Of course, if the terrorist group were to steal a finished nuclear weapon and acquired an ability to detonate it, then the risk to the United States and allies would be much higher (see Mueller, 2010).

outcome and choose simultaneously on the basis of the two-sided information available to them.

Recent modeling efforts have analyzed theoretical solutions to the 2 × 2 game under conditions of incomplete information, when the players do not share accurate information about each other’s preference rankings. Each is instead playing a different subjective game, and the outcome of their strategic interaction is the intersection of their choices based on their respective subjective games (Maoz, 1990; Walker et al., 2011). The rules of play also stipulate alternating rather than simultaneous moves based on information from revealed preferences inferred from prior behavior or pre-play communication between the players.

These two changes increase the likely external validity of the model and its usefulness for understanding adversaries and allies in deterrence and assurance situations in real-world interactions. The results of these more realistic games can identify the distribution of risk-acceptant and risk-averse paths forward for the United States and its adversaries and allies regarding the problems of deterring the escalation of conflicts and dissuading the spread of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction. A world of nuclear-armed powers in several regions increases the risk of escalation to a nuclear war from a conventional war and makes it desirable to focus increased attention on general deterrence and the dissuasion of nuclear proliferation, so that the occurrence of crisis and near-crisis situations involving extended and immediate deterrence actions are minimized.

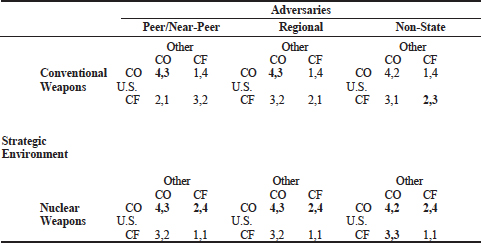

Game theory provides a set of abstract models to represent the types of adversaries and allies that are possible in these security environments. The possible situations with the three types of actors (peers/near-peers, regional, and non-state actors) shown in Figure D-3 are represented as having different distributions of military capabilities in two types of strategic environments. The two players (U.S. and Other) rank their preferences from (4) highest to (1) lowest for the four outcomes (cells) where their choices of Cooperate (CO) or Conflict (CF) intersect as possible solutions to the game: mutual cooperation (CO,CO), mutual conflict (CF,CF), domination by one player and submission by the other player (CO,CF) or (CF,CO). For example, in the United States, peer/near- peer game, the (CO,CF) outcome of (1,4) is the lowest-ranked outcome of submission (1) for the United States and the highest-ranked outcome of domination (4) for Other. Conversely, the (CF,CO) outcome of (4,1) in the same game is the highest-ranked outcome of domination (4) for the U.S. and the lowest-ranked outcome of submission (1) for Other.

In a world of conventional weapons with peer/near-peer, regional, and nonstate actors, the United States has the military capabilities to dissuade allies who are not assured by the U.S. strategy toward adversaries and, if necessary, dominate (CF,CO) or block (CF,CF) an adversary or ally if the other player refuses mutual cooperation (CO,CO) as the equilibrium solution. However, in the world of nuclear

FIGURE D-3 U.S. games with types of adversaries in different strategic environments. The solutions from the Theory of Moves (TOM) are in bold (Brams, 1994). Cooperation (CO) and Conflict (CF) are the choices for each player, which can intersect and result in the following possible outcomes: mutual cooperation (CO,CO); row submits and column dominates (CO,CF); mutual conflict (CF,CF); row dominates and column submits (CF, CO).The logic of these conflict games also applies to allies who disagree with the U.S. strategy of ranking (CO,CO) as the highest outcome. Two players who agree on the highest-ranked outcome play a no-conflict game, with that outcome as the game’s solution. SOURCE: Brams (1994, Appendix).

capabilities in Figure D-3 the U.S. ability to dominate (CF,CO) is in question, and deadlock (CF,CF) is a very risky outcome as both players in each game rank deadlock as the lowest-ranked outcome. In this strategic environment the risk of deadlock is nuclear war as the final outcome of a conflict, which would pose an existential threat to what each player wishes to protect.7

The solutions for all of these games with alternating moves and prior communication between players as the rules of play represent the logical outcomes in these two worlds if the United States chooses deterrence and assurance as its strategy

________________

7 This existential deterrent effect may have different referents in addition to or instead of the existence of the decision unit, such as family members, religious institutions, or a revolutionary movement that members of the decision unit hold dear. A deterrent threat will by definition not work against a completely nihilistic adversary who does not care whether anyone or anything survives a war.

for managing and resolving conflicts.8 It is important to understand as well that deterrence/assurance is not the only strategy available to the United States in these two worlds. The focus here is on the logical consequences of a deterrence/assurance strategy, because this strategy is the current strategy of the United States and the mission of the U.S. Air Force.

The results in Figure D-3 illustrate the continued value of game theory as a tool to specify conflict situations with potential adversaries in which assumptions are made about the preferences of each player for the possible outcomes to the game. They show that if hard power (military capabilities) really matters, then the games (strategic interaction situations) against different types of adversaries have different outcomes for a deter/assure strategy of threats and promises by the United States. The U.S. outcomes depend as well on whether it is a world of conventional or nuclear weapons, even if the power position of the United States in the world changes or if the United States changes its strategy toward potential adversaries, because the introduction of nuclear weapons alters the ranking of each player’s preference rankings for the possible outcomes of their games.

Finally, the results in Figure D-3 demonstrate how if the two players are truly strategic, that is, open to the information about their respective power positions in the world and aware of the nature of the outcomes of a nuclear war between them then when a CF,CF deadlock risking nuclear war is ranked lowest (1), the asymmetrical conventional superiority of the United State does not guarantee the outcomes of either settlement (CO,CO) or U.S. domination (CF, CO) as a solution to the strategic interaction problem. In a game of multiple equilibrium solutions, therefore, it is not always desirable in some cases for the United States to confront a nuclear adversary.

For example, a projection of the submission outcome (2,4) in Figure D-3 for the United States as the equilibrium solution in a nuclear strategic environment is a sufficient condition for the United States to consider disengaging militarily from this type of conflict situation under certain conditions of play against any type of

________________

8 In sequential game theory a strategy “is a complete plan that specifies the exact course of action a player will follow, whatever contingency arises” (Brams, 1994, p. 227). Strategies are distinguished and specified further here by the rank order of the four outcomes: mutual cooperation (CO,CO); mutual conflict (CF,CF); U.S. domination (CF,CO), U.S. submission (CO,CF). There are four families of strategies whose members share one of these four outcomes as the top-ranked outcome; members within each family of strategies are differentiated by variations in the rankings of the remaining three outcomes. For example, a deter/assure strategy ranks CO,CO as the highest ranked outcome. In Figure D-3, the U.S. deter/assure strategies in a strategic environment of conventional weapons rank CO,CO highest (4), CF,CF (3), CF,CO (2), CO,CF lowest (1) toward peers/near peers; the rankings are CO,CO (4), CF,CO (3), CF,CF (2), CO,CF (1) against regional and non-state actors. More generally, variations in rankings are specified by assumptions about differences in the distributions of power and interests between players (Walker, 2013).

adversary—peer/near-peer, regional, or non-state actor. 9 Instead, it should pursue its interests indirectly with soft power (diplomatic and economic tools of statecraft) to assure allies and isolate the adversary rather than employ hard power (military tools of statecraft) directly in an attempt to deter an adversary or dissuade an ally.10

It is important as well to acknowledge that these abstract, game-theoretic models may not have external validity. In the real world of historical cases between the United States and the three types of actors in Figure D-3, the assumptions in the model may not always be present. Each player may instead rank the four possible outcomes differently than the ones specified in this figure, or they may make decisions that are not based on information about all possible outcomes and the distribution of military capabilities between them. Specifically, if an adversary armed with nuclear weapons is not open (receptive) to deterrent threats, especially if backed into a corner with no way out, then it might elect to use those weapons first in a conflict for four reasons. First, the United States is very likely to win a conventional war, and defeat would mean the adversary state’s leadership would lose power and perhaps their lives. Second, U.S. and allied airstrikes likely would force the adversary’s leaders into a use-or-lose dilemma regarding their nuclear and other WMD capabilities. Third, the adversary might be tempted to use nuclear explosives to create electromagnetic pulse effects that would help level the playing field against a technically superior U.S. force. They might believe that since EMP was relatively bloodless, it might not provoke a nuclear response from the United States. Fourth, if an adversary was about to go down to defeat, it could elect to launch a revenge nuclear strike on U.S. forces, allies, and—in the future—against the U.S. homeland.

REFERENCES

Allison, G. 1969. Conceptual models and the Cuban missile crisis. The American Political Science Review 63(3):689-718.

Allison, G., and P. Zelikow. 1999. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, 2nd Ed. Longman, New York.

Brams, S. 1994. Theory of Moves. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York.

Braybrooke, D., and C. Lindblom. 1963. A Strategy of Decision. Free Press, New York.

Brecher, M., and J. Wilkenfeld. 2000. A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

________________

9 In the games in the nuclear strategic environment shown in Figure D-3 with multiple equilibria as stable outcomes, the actual final outcome depends on the order of play (who has the next move) from each possible initial state (cell) at the beginning of the game, whether preplay communication of threats and promises is allowed between the players, and whether the game is likely to be repeated between the two players (Brams, 1994). These conditions may not always favor the United States in an actual historical situation.

10 The logical implications of these two strategies for exercising power directly or indirectly against an adversary are modeled with game theory in Walker and Malici (2011, Appendix, pp. 303-304).

Bunn, E. 2007. Can deterrence be tailored? Strategic Forum 225(January).

Campbell, A., W. Miller, and D. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Cobb, R., and C. Elder. 1970. International Community; A Regional and Global Study. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York.

Department of Defense. 2006. Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) Report. Washington, D.C., p 2.

Deutsch, aK. 1954. Political Community at the North Atlantic Level. Doubleday, Garden City, N.J.

Deutsch, K., and J.D. Singer. 1964. Multipolar power systems and international stability. World Politics 16:390-406.

Ellsberg, D. 1961. The crude analysis of strategic choices. American Economic Review 51:472-478.

Etheredge, L. 1978. A World of Men. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Greenstein, F. 1987. Personality and Politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Hermann, C. 1969. Crisis in Foreign Policy. Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, Ind.

Hermann, C., ed. 1972. International Crises. Free Press New York.

Hermann, M. 2001. How decision units shape foreign policy. International Studies Review 3:47-81.

Hermann, M. 2003. Assessing leadership style: Trait analysis. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Hermann, M., and C. Hermann. 1989. Who makes foreign policy decisions and how? International Studies Quarterly 33:361-388.

Hermann, M., and T. Preston. 1994. Presidential advisors and foreign policy. Political Psychology 15:75-96.

Jervis, R. 1976. Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Jervis, R., and J. Snyder, eds. 1991. Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Great Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland. Oxford, New York.

Kegley, C., and E. Witkopf. 1982. American Foreign Policy. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Khong, Y. 1992. Analogies at War. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Kowert, P. 2002. Groupthink or Deadlock? SUNY Press, Albany, N.Y.

Kowert, P., and M. Hermann. 1997. Who takes risks? Journal of Conflict Resolution 41:611-637.

Kruglanski, A. 2004. The Psychology of Close-Mindedness. Psychology Press, New York.

Kupchan, C. 1994. The Vulnerability of Empire. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Lowther, A. 2013a. Thinking about Deterrence. Air University Press, Maxwell, Ala.

Lowther, A. 2013b. Deterring non-state actors. In Thinking About Deterrence (A. Lowther, ed.). Air University Press, Maxwell, Ala.

Maoz, Z. 1990. National Choices and International Processes. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Morgan, P. 1983. Deterrence: A Conceptual Analysis. Sage, Beverly Hills, Calif.

Morgan, P.M. 2003. Deterrence Now. Cambridge University Press, London.

Most, B., and H. Starr. 1989. Inquiry, Logic, and International Politics. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, S.C.

Mueller, J. 2010. Atomic Obsession. Oxford University Press, New York.

Neustadt, R., and E. May. 1986. Thinking in Time: The Uses of History for Decision Makers. Free Press, New York.

Nye, J. 1990. Bound to Lead. Basic Books, New York.

Nye, J. 2011. The Future of Power. Public Affairs Press, New York.

Parish, K. 2013. U.S., South Korea announce ‘tailored deterrence’ strategy. American Forces Press Service. http://www.defense.gov/newsarticle.aspx?id=120896.

Post, J., ed. 2003. The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Post, J. 2012. Actor-specific behavioral models of adversaries. In Tailoring Deterrence (B. Schneider and P. Ellis, eds.). USAF Counterproliferation Center, Maxwell, Ala.

Rasler, K., W. Thompson, and S. Ganguli. 2013. How Rivalries End. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa.

Rokeach, M. 1960. The Open and Closed Mind. Basic Books, New York.

Rosati, J. 1981. Developing a systematic decision-making framework. World Politics 33:234-252.

Rosenau, J. 1966. Pre-theories and theories of foreign policy. In Approaches to Comparative and International Politics (R. Barry Farrell, ed.). Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Schafer, M., and Crichlow, S. 2010. Groupthink v. High-Quality Decision Making in International Relations. Columbia University Press, New York.

Schaub, G. 2013. Deterring rogues: Modeling the intent of revolutionary actors. In Thinking about Deterrence (A. Lowther, ed.). Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala.

Schelling, T. 1960. Strategy of Conflict. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Schelling, T. 1966. Arms and Influence. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Schneider, B., and P. Ellis. 2012. Tailoring Deterrence, 2nd ed. USAF Counterproliferation Center, Maxwell, Ala.

Solingen, E. 1998. Regional Orders at Century’s Dawn. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Solingen, E. 2007. Nuclear Logics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Sprout, H., and M. Sprout. 1956. Man-Milieu Relationship Hypotheses in the Context of International Politics. Princeton University Center for International Studies, Princeton, N.J.

‘t Hart, P., E. Stern, and B. Sundelius, 1997. Beyond Groupthink. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Trexel, J. 2013. Tailored deterrence, smart power, and the long-term challenge of nuclear proliferation. In Thinking about Deterrence (A. Lowther, ed.). Air University Press, Maxwell, Ala.

Tuchman, B. 1984. The March of Folly. Random House, New York.

Walker, S. 2013. Role Theory and the Cognitive Architecture of British Appeasement Decisions. Routledge, New York.

Walker, S., and A. Malici. 2011. U.S. Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif.

Walker, S., and G. Watson, 1992. The cognitive maps of British leaders, 1938-39. In Political Psychology and Foreign Policy (E. Singer and V. Hudson, eds.). Westview, Boulder, Colo.

Walker, S., M. Schafer, and M. Young. 2003a. Profiling the operational codes of political leaders. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Walker, S., M. Schafer, and M. Young. 2003b. Saddam Hussein: Operational code beliefs and object appraisal. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Walker, S., A. Malici, and M. Schafer. 2011. Rethinking Foreign Policy Analysis. Routledge, New York.

Waltz, K. 1959. Man, the State, and War. Columbia, New York.

Waltz, K. 1964. The stability of a bipolar world. Daedelus 93:881-909.

Winter, D. 2003. Measuring the motives of political actors at a distance. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Wolf, C. 1967. United States Policy and the Third World: Problems and Analysis. Little, Brown and Co., Boston, Mass.