INTRODUCTION

Can behavioral science research into the local knowledge of the personalities and cultures of state and non-state actors provide actor-specific knowledge for tailoring a U.S. communications strategy designed to deter adversaries, assure allies, and dissuade both adversaries and allies from developing, expanding, and using weapons of mass destruction (WMD) capabilities? This chapter discusses how actor-specific knowledge and the tools that can inform it—for example, leader personality profiling and both automated and expert-intensive content analysis, are useful for doing so, particularly in helping tailor communications with both adversaries and allies. They can help (1) assess whether the “decision unit” (predominant leader, single group, or multiple autonomous actors) is “open” or “closed” to receiving a deterrence or assurance message and (2) whether the decision unit is relatively risk-averse or risk-acceptant in its strategic orientation toward action.

WHICH COMMUNICATIONS CAPABILITIES DETER AND WHICH ASSURE?

The basic stimulus-response behavioral model of communications and information theory is relatively clear as a descriptive model (Shannon and Weaver, 1964;

Holsti et al., 1968). A message in the form of an action (e.g., a threat or promise) is sent by Actor A as the stimulus (S). Actor B receives this message and follows with a response (R) in the form of cooperation or conflict behavior. Social scientists have scales and indices that can measure (S) and (R) to see if there is congruence between them, i.e., whether S and R “match up” (correlate) in the way intended by Actor A. If so, then the outcome is deterrence or assurance success, and if not, then the outcome is deterrence or assurance failure.

However, it is not so clear what the intervening causal processes are that account for the correlation between S and R, or how these explanatory models can be specified and measured. The conventional model in the classical deterrence literature assumes a causal mechanism of “economic rationality,” in which costs (c) and benefits (b) are calculated by Actor B. For the simple case of B having only the choices of escalating or deescalating, then if (c) > (b) regarding escalation (e) and if (b) > (c) regarding de-escalation (d), then Actor B will choose deescalation (d) (see Ellsberg, 1961; Robbins, et al., 2013). Unfortunately, it is difficult both conceptually and empirically to define and measure (c) and (b) with reasonable reliability and validity. In addition, there are problems, discussed in Chapter 2 of this report, such as the actors may not in fact have stable utilities and may not base their actions on “expected-value” calculations as assumed by the original notions of economic rationality.

Another basic assumption in rational choice models of deterrence and reassurance is that the both Actor A and Actor B understand the costs and benefits in the same way. These assumptions are at best first approximations and, at worst, they are radically wrong under real-world circumstances in which threats and promises may be exchanged between Actor A and Actor B but are communicated or interpreted ineffectively. Motivational and emotional biases, such as fear, anger, or mistrust, and cognitive biases, such as ideological beliefs or cultural norms, may distort the identification, weighting, and calculation of costs or benefits.

The result is a choice that follows rational procedures in the sense of actors trying to relate ends and means, but it may be unwise because of distorted perceptions at the point of decision (Post, 2003a; Downes-Martin, 2013; see also Holsti et al., 1968; Zinnes, 1968; Holsti, 1972; Jervis, 1976; Fiske and Taylor, 1991; Davis and Arquilla, 1991; Steinberg, 1996). The influence of these actor-specific factors is heightened under certain stressful decision-making conditions when a crisis situation, defined as a surprise involving high stakes with a short time in which to respond, is the occasion for decision (Hermann, 1969, 1972; Brecher and Wilkenfeld, 2000).1

________________

1 Deterrence theorists also recognize shortcomings of the rational choice mechanism connecting threats and responses (Morgan, 2003). It is often argued that the value of the rational choice model lies in its value as a normative standard against which to assess what is actually occurring in strategic

These problems are compounded when the mechanisms connecting S and R are social as well as psychological. If multiple actors are involved rather than a single predominant leader, then results may depend on complex interactions among the various individual cost-benefit equations, as well as the effects of imperfect communications and power relationships. The results may therefore be unpredictable. To put it differently, trying to open the black box and understand the intermediate causal mechanisms leading to a decision inside a predominant leader, within a single group, or among a coalition of autonomous actors may not be feasible by outside observers, especially if they lack the tools for decoding their interactions and organizational context (t’Hart et al., 1997; Schafer and Crichlow, 2010; Allison and Zelikow, 1999).

A strategy of tailored deterrence and assurance attempts to reduce the gaps between the rational model implying desired results and the psychological and social mechanisms that generate the actual results. The particular emphasis in this chapter is on the psychological mechanisms of object appraisal, mediation of self–other relations, and ego defense identified in Appendix D (see Figure D-1).2 The basic communications problem to be solved is reducing the problem of uncertainty in the decision-making environment for Actor A in dealing with Actor B as an adversary or an ally. There may be uncertainty about the capabilities, goals, or intentions of Actor B. In the absence of direct and updated evidence (new information) about these items, decision makers in Actor A may substitute beliefs (old information) inferred vicariously from lessons learned in previous personal encounters or analogous situations (Jervis, 1976; Neustadt and May, 1986; Larson, 1985; Vertzberger, 1990).

The recall of this information may be accompanied by undesirable emotional tags in the form of the arousal of motivations or feelings that were actually stimulated earlier by the actions of the other actor and shaped the recall of inappropriate analogies (De Rivera, 1968; Jervis, 1976; Zajonc, 1980; Steinberg, 1996; Post, 2003a; Marcus, 2003; Neumann et al., 2007; Downes-Martin, 2013). Therefore, it can be important for Actor A to know B’s psychology as well as B’s sense of power balances and utilities, in order to tailor the communication of a threat or promise

________________

interactions and then taking steps to share more information and thereby increase the chances of a rational response and outcome in subsequent interactions (Fearon, 1994a,b; Zagare and Kilgore, 2000; Glaser, 2010). The debate over whether and how the actual mechanism needs to be specified correctly in order to understand how deterrence works is the subject of a symposium in World Politics (Downes, 1989), an edited volume by Geva and Mintz (1997), and a book by Morgan (2003). As discussed in Chapter 2, another view is that the economic-rationality model is not necessarily a good normative model and is certainly not descriptive: Different decision styles are appropriate, not just common, in different types of circumstances.

2 The social mechanisms also identified in Figure D-1 were discussed in Appendix D.

accordingly. What are the available profiling methods and tools for accessing this psychological knowledge?

An individual’s basic personality characteristics are relatively stable traits that are inherited genetically and shaped into different configurations or syndromes by childhood and adolescent psychobiographical experiences; they are relatively constant and not likely to change without psychiatric treatment or perhaps genuinely life-altering experiences (Post, 2003a). However, these structural characteristics of the personality system are not all equally relevant for explaining political behavior, as different situations are likely to selectively engage aspects of the basic personality system as causal mechanisms (Funk et al., 2013). For example, an individual with a narcissistic personality syndrome that is characterized by a motivation to seek glory and adulation from others to compensate for underlying self-doubts may be more likely to seek careers in the public arena of politics as well as other venues of social life where a leading role is available.

In immediate political situations these enduring structural personality characteristics may act as unconscious influences that condition the range of options a leader considers, and they perhaps influence the actual choice of actions in ways that outside observers would deem “radically irrational”—that is, as triggered and driven by unconscious emotional and motivational impulses unmediated by conscious thoughts and beliefs and information available from the environment (Simon, 1985). While constant features of a leader’s personality structure may define the character of the leader and influence all of his political decisions, three questions also arise: How exactly do these structural features of the personality system influence a decision? Is it a matter of kind or degree? When (in what situations) do they matter and at which stages in the decision-making process are they relatively unimportant?

There are two ways to answer such questions in linking personality with decisions: (1) pursue a top-down strategy that defines the leader’s basic personality structure from psychobiographical evidence remotely located from the occasion for decision and then examine how proximate processes of cognition, emotion, and motivation associated with an immediate decision-making situation link personality structure with political behavior or (2) pursue a bottom-up strategy that first examines those proximate processes that are direct causal mechanisms of behavior in the immediate decision-making situation and then contextualize these results by linking them with the underlying structure of the leader’s personality.

These two approaches characterize the leadership profiling literature in political psychology and are illustrated in this chapter with their application to the personality of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in the decision-making situations that he faced in the 1990-91 Persian Gulf conflict with the United States and its allies. The example of the Persian Gulf conflict includes efforts by the U.S. government to deter an attack on Kuwait by Iraq and subsequently to coerce Iraq’s withdrawal

from Kuwait. The following analysis presents brief illustrations of several profiling methods for analyzing actor-specific knowledge relevant for making tailored deterrence and assurance decisions. The examples all draw on the case of Saddam Hussein as a predominant leader who was neither deterred from invading Kuwait in 1990 nor persuaded to withdraw voluntarily in 1991.

The first example is a summary of the top-down, holistic study of the Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein by Post (2003b), which was presented in testimony before the House Armed Services and Foreign Affairs Committee in December 1990. The method employed in this study is the use of available historical and psychobiographical sources to construct a political personality profile of a leader’s basic personality type, such as one of the three examples in Table E-1.

TABLE E-1 Examples of Types of Basic Personality Structure and Leadership Styles

| Example of Political Personality Types | |||

| Mechanism | Narcissistic | Obsessive-Compulsive | Paranoid |

| Ego defenses | Grandiose self, sense of superiority, and denial. | Abhorrence of emotionality that implies lack of control. | Suspiciousness and mistrust |

| Externalization | Projects arrogance and grandiose self-image. hypervigilance. | Projects fixation with rules, order, efficiency, isolates, rigid, sublimates, intellectualizes. | Projects hostility and stubborn |

| Mediation of self–other relations | Hunger for reassurance and vulnerability to criticism, lacks empathy. Exploitative, sense of entitlement. | Preoccupied with relative status, is oppositional or domineering. Formal, over moralistic, micro- manages, does not delegate. | Fear of closeness, projection, search for enemies and distrusts all. |

| Object appraisal | Dogmatic certainty and manipulation of information. | Attention to detail and insistence on rational information processing. Less aware of big picture. | Exaggerates danger and capabilities of adversaries. Black and white thinking. |

| Decision-making orientation | Risk-averse and dominated by centrality of self. Identifies self-interest with country. | Risk-averse and perfectionistic with decisions avoided, deferred, protracted, and based on expertise. | Risk-averse and worst-case thinking based on competitive advisors. |

| Leadership style | Search for glory and recognition | Driven, deliberate, myopic, dominated by shoulds, not wants, and search for certainty | Strongly prefers use of force over persuasion. |

| Prototype | Saddam Hussein | Menachem Begin | Josef Stalin |

NOTE: The personality characteristics in this table are representative, but they do not exhaust the defining features of each personality type.

SOURCE: Based on information from Post (2003a).

Iraq under Saddam is an exemplar of a society with a predominant leader. In such situations, it is imperative to have a nuanced personality profile of the leader. As was regularly stated, “Saddam is Iraq, Iraq is Saddam” (Post, 2003b, p. 343). Post diagnosed Saddam Hussein’s basic personality type as “malignant narcissism” (a narcissist with a paranoid outlook, absence of conscience, and a willingness to use whatever aggression is required to accomplish his goals). While psychologically in touch with reality and not “crazy” in a clinical sense, Saddam was often out of touch with political reality. He was surrounded by a group of sycophants who, for good reasons, were reluctant to criticize his decision making and told him what he wanted to hear rather than what he needed to hear. To disagree with Saddam was to lose one’s job or lose one’s life (Post, 2003b).

An examination of Saddam’s career reveals a number of occasions when he reversed course, considering himself a “revolutionary pragmatist” (Post, 2003b). Why then was Saddam, who was characterized as risk-averse, not deterred from invading Kuwait? Further, why was he not responsive to coercive diplomacy by the United States in the form of a massive military buildup and threatened air campaign as the January deadline approached for him to withdraw Iraqi forces from Kuwait? Why did he not reverse himself as he had in the past and withdraw from Kuwait? 3

With intelligence indicators and warnings that Saddam was planning an invasion of Kuwait and Iraqi troops massing on the border, U.S. Ambassador April Glaspie was instructed to inform Saddam that the United States considered the territorial dispute between Iraq and Kuwait to be an Arab-Arab dispute and that the U.S. government did not take a position on it. She was to be clear in expressing the hope and expectation that Iraq and Kuwait would settle their differences peacefully. There was no overt threat of a U.S. military response should Kuwait be invaded. Glaspie’s message did not represent a clear cease-and-desist message (Schneider, 2012). Although Saddam did not see the demarche as a green light to invade Kuwait, he also did not calculate accurately the risk of a massive U.S. response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait (Freedman and Karsh, 1993, pp. 47-61). 4

________________

3 Saddam’s past course reversals include (1) yielding on the Shatt al Arab issue with Iran to quell Kurdish rebellion; (2) attempting to end the Iraq-Iran war; (3) yielding to Iran on the Shatt al Arab waterway issue to end their war; (4) releasing all foreign hostages during Persian Gulf crisis. See Post (2003b, pp. 340-342).

4 It was not only that the Glaspie message contained no threat. The United States had not deployed aircraft carriers to the region, and it seemed unlikely that even if it wanted to act militarily, it could not do much because the Saudis would not accept U.S. forces. Further, it seemed that the United States did not have much stomach for casualties, as evidenced by Vietnam and the pull-out of forces from Lebanon. Saddam also greatly underestimated the effects of modern air power and had no idea how totally over-matched his ground forces were. Even though he seems to have rationally contemplated risks, he underestimated them greatly while at the same time having grandiose ambitions. For other discussions of Saddam’s potential and actual thinking, see Davis and Arquilla (1991), Stein (1991), and Brands and Palkki (2012). The analysis of Saddam Hussein’s perceptions and misperceptions by

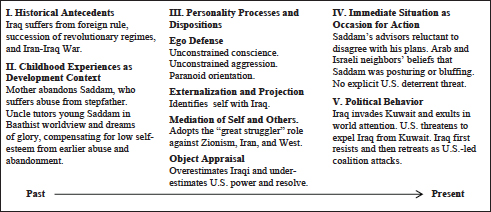

FIGURE E-1 Map of Saddam Hussein’s political personality and behavior. NOTE: The map’s narrative locations are numbered left to right in temporal order from I to V. SOURCE: Based on information from Post (2003b); map adapted from Smith (1968) in Greenstein and Lerner (1971, p. 38).

Following Iraq’s invasion and occupation of Kuwait, however, U.S. intentions were not ambiguous. If Iraq did not withdraw from Kuwait, the United States threatened the massive destruction of Saddam’s military might. This threat was communicated not only with mere words, but with evidence on the ground in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf of a massive U.S. buildup preparing for military action. To understand why Saddam stood fast in the face of this imminent threat, one must consider the psychodynamic effects of the conflict thus far on Saddam, and the psychobiography-based political personality profile predicting Saddam’s likely behavior summarized in Figure E-1 and discussed below.

As the map in Figure E-1 shows, this perspective highlights Saddam‘s background as one of a deeply traumatized individual, a wounded self, dating back to the womb. Saddam’s father had died of cancer during the fourth month of his mother’s pregnancy with Saddam. In the eighth month, her first born son died under a surgeon’s knife. Understandably deeply depressed, Saddam’s mother first tried to abort herself of the pregnancy with Saddam and then made a suicide attempt. When Saddam was born, she turned away from him and finally gave his care to her brother Khairallah, who raised Saddam for the first two and a half years of his life, when his mother remarried and the new step-father was physically and

________________

Woods and Stout (2010) reflects extensive documentary material gathered after the 2003 war with Iraq.psychologically abusive to young Saddam. At age 8, when his parents refused Saddam’s request to go to school, he fled back to his uncle Khairallah (Post, 2003b).

His Uncle Khairallaha filled young Saddam with dreams of glory, telling him some day he would be listed among the great heroes of Iraq and the Arab world, Saladin and Nebuchadnezzar. The dramatic invasion of Kuwait, which drew the attention of the world to the Iraqi leader, consummated his aspiration to be an important world leader, nurtured since childhood and accompanying his rise to regional prominence in the Middle East. It was dreams of glory fulfilled. As a narcissistic personality he could not then easily reverse himself without opening old psychological wounds unless there was a way that he could declare victory and withdraw (Post, 2003b).

So the notion that Saddam Hussein would respond to threatened military action and, humiliated, retreat from Kuwait to his previous obscurity was not intuitively obvious. He had reversed himself in the past; however, these reversals had only occurred when he could do so without loss of face while retaining his power.5 By mid-December, 1990 Saddam Hussein was adamant and had resolved to stand fast. When Secretary of State Baker had his last-minute diplomatic visit with Iraqi Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz, he found that Saddam Hussein was no longer open to complying with a U.S. compellent threat to withdraw or face expulsion by military force (Post, 2003b; Schneider, 2012).

The second type of analysis is a bottom-up approach that focuses on the proximate causal mechanisms of ego defense, externalization, mediation of self–other relations, and object appraisal under Personality Processes and Dispositions in Figure E-1 that connect a leader’s personality traits, motivations, and cognitions

________________

5 This condition was not met when U.S. President George H.W. Bush pounded on a table, declaring, “There will be no face saving,” and a leak from a U.S. general (subsequently forced to retire early) indicated that the U.S. contingency plans were to kill Saddam. In this context, it was not irrational for Saddam to believe that he did not have a way out of the conflict with the United States. Moreover, his decision to absorb the anticipated massive airstrike was buffered by his belief that the United States still suffered from a Vietnam syndrome, and if he could withstand the airstrike and get involved in a ground campaign, the specter of U.S. troops being returned in body bags would lead to massive U.S. protests against the Pentagon and White House, leading to a political stalemate. Saddam, by having the courage to stand up to the U.S. superpower, would win a hero’s mantle. Indeed, on the fifth day of combat, Saddam held a press conference and declared victory. It was explained to the incredulous press that it was widely believed that Iraq could not withstand more than 3 days of the air attack with smart bombs and guided missiles, and had already survived for 5 days. Each further day would only magnify the scope of the victory (see Post, 2003b). Saddam Hussein had stated previously in an interview on German television the belief that the United States would end the conflict once they had lost 5,000 or more killed in action, which unfortunately for the Iraqi leader did not happen (see Schneider, 2012, p. 217). RAND work at the time also foresaw Saddam’s being willing to fight but, if necessary, to find a way to exit later if need be. The analysis was influenced by the belief that Saddam would assume that the U.S. would violate any agreement; other considerations were also part of the analysis (Davis and Arquilla, 1991, pp. 53-61; see also Brands and Palkk, 2012).

with decisions and leadership style within the boundaries set by the leader’s character. The method employed to study these mechanisms is quantitative content analysis, which detects variations in the operation of these causal mechanisms, in contrast to qualitative content analysis, which identifies character structure as a constant in a leader’s personality. The tools associated with quantitative content analysis are scales and indices that summarize the central tendency and range of variation over time in the cognitive, motivational, and other psychological traits in a leader’s personality.

In contrast to a leader’s character, these features of the leader’s personality are relatively more plastic features that change shape over time in response to changing environmental conditions. While different leaders may have different structural configurations of personality traits that transcend situations and define character, a leader’s individual personality traits also become aroused in different degrees and combinations, depending on environmental stimuli. So Leader A’s significant difference from Leader B in self-confidence may remain robust across situations, but the intensity and influence of self-confidence in combination with other personality traits on behavior may vary for each leader in the same situation.

Similarly, different situations arouse different motivations within a leader’s personality—for example, a conflict situation with adversaries may engage a leader’s need for power, while a cooperation situation with allies may arouse a leader’s need for affiliation (Winter, 2003a). The same is true for a leader’s cognitions, because different configurations of beliefs and levels of cognitive complexity may be triggered as mechanisms to assist a leader’s information processing and decision-making in different situations (Suedfeld et al., 2003; Walker, 2013).

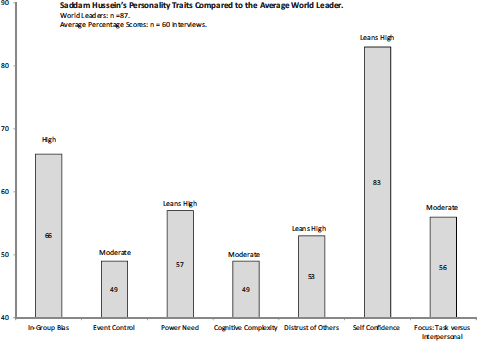

Saddam Hussein’s personality traits associated with the externalization of his leadership style via his motivational and cognitive processes associated with the mediation of self–other relations and object appraisal displayed these variations across different periods and situational contexts preceding, during, and following the 1991 Gulf war. In Figure E-2, his mean scores on seven personality traits differentiated him from the average Middle East leader and the average world leader: “Saddam Hussein is different from the two samples of leaders on over half of the traits—nationalism, need for power, distrust of others, and self-confidence. He is like other leaders with regard to his belief that he can control events, conceptual complexity, and his focus on accomplishing something versus focusing on the people involved…” (Hermann, 2003b, p. 376).

The four traits that distinguished the Iraqi leader from others also varied significantly across contexts. His conceptual complexity was significantly lower (.27) in the 1991 Gulf War period in contrast to the pre-Iranian War (.50) and Iran-Iraq War (.55) periods. The nationalism trait was significantly higher (.72) in the Gulf War than in his relations with either Arabs or non-Arabs (.58). His need for power (.39) was strikingly lower in domestic politics and during the Gulf War than the

FIGURE E-2 Fluctuations in Saddam Hussein’s personality profile. SOURCE: Based on Post (2003a); data from Table 17.1 in Hermann (2003b).

range of his need for power scores (.53 to .69) in dealing with the Kurds and relations with both Arabs and non-Arabs. His distrust of others was elevated during the Gulf War (.68) and the Iran-Iraq War (.66) periods and in dealing with the Kurds (.65), in contrast to domestic politics (.39) and relations with both Arabs (.44) and non-Arabs (.49), which had lower scores (Hermann, 2003b, p. 383).

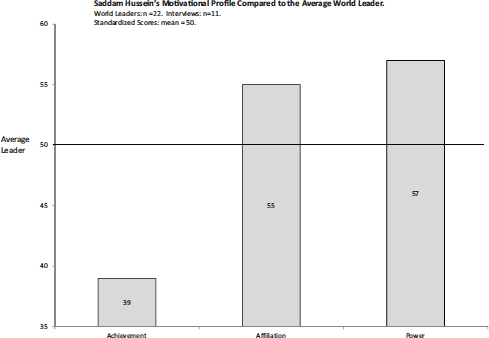

Saddam Hussein’s motivational profile regarding the needs for power, affiliation, and achievement over a 17-year period between 1974 and 1991 showed that he had a “quite high power motivation, above average affiliation motivation, and very low achievement motivation” in comparison with the average world leader in a sample of 22 world leaders from a variety of geographical regions occupying different political roles (Winter, 2003b, p. 371). The results in Figure E-3 from a content analysis of 11 interviews are relatively stable when broken down by different sources (more versus less spontaneous interviews). The results are consistent with Post’s structural personality profile that emphasizes Saddam’s “extreme narcis-

FIGURE E-3 Saddam Hussein’s motivational profile. SOURCE: Based on Post (2003a); data from Table 16.2 in Winter (2003b).

sism, exalted and extravagant rhetoric, aggression as an instrument of policy, and a paranoid fear of enemies” (Winter, 2003b, p. 372).

The two-point difference between the Iraqi leader’s power and affiliation scores is also consistent with Hermann’s observations of fluctuations in Saddam’s personality traits aroused in his relations with different “others” in different situations. His high need- for-affiliation score indicates a capacity to cooperate with an in-group of like-minded people from his own family and village and be defensive and “prickly” in the wider world of Iraqi politics and foreign strangers. The same dynamic characterizes Saddam’s relations with “brother” Arabs and his defiant and hostile relations with adversaries in stressful crisis situations (Winter, 2003b, p. 373).

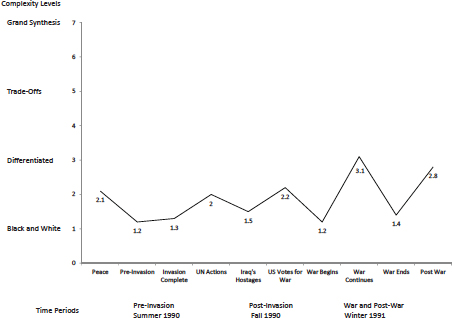

The same patterns of and volatility and stability that characterize the externalization of personality traits and the mediation of self–other relations regarding motivations are evident in the object appraisal patterns displayed in the cognitive complexity patterns of Saddam Hussein in Figure E-4. The processes of object ap-

FIGURE E-4 Saddam Hussein’s Gulf War patterns of cognitive complexity. SOURCE: Data from Table 18.2 in Suedfeld (2003).

praisal are the most conscious causal mechanisms in the leader’s personality system and reflect how overt decisions are reached to pursue or maintain goals and select the means to achieve or protect them.

Saddam’s cognitive complexity scored lower during the Gulf crisis (not shown in Figure E-4) leaders of other less-involved nations. “This finding supports the disruptive stress hypothesis, which states that severe and/or prolonged stress leads to reduced complexity because of a depletion of psychological and other resources” (Suedfeld, 2003, p. 393). However, prior to the Gulf crisis, Saddam’s complexity was relatively high. It then dropped immediately prior to the decision to invade Kuwait, before rising after the invasion was successful and his stress level had decreased (Suedfeld, 2003, p. 393).

The cognitive complexity indices for Saddam Hussein in Figure E-4 continued to be relatively volatile during the ensuing confrontation with the United States and UN coalition forces. The overall pattern is consistent with Post’s “great struggler” finding as Saddam’s political role in Middle East and global politics. “New actions against him, rather than motivating him to search for compromise, buttress a uni-dimensional strategy; more cognitive investment in a differentiated and integrated

viewpoint occurs when it becomes obvious that the simple strategy is unavailing” (Suedfeld, 2003, p. 395).

This pattern of stubborn resilience, as shown in Figure E-4 during the run-up to war following his invasion of Kuwait, was punctuated by sharp drops in complexity levels with the onset of the air and ground war attacks on Iraq and the defeat of the Iraqi army by coalition forces before rising to a prewar level with the beginning of postwar restructuring inside Iraq. Overall, the cognitive complexity results in Figure E-4 express his cognitive style and reflect variations in Saddam Hussein’s level of cognitive effort during the Persian Gulf conflict, as he attempted to reconcile stimuli from the environment with the cognitive dispositions in his belief system (Suedfeld, 2003).

An example of the contents of the Iraqi leader’s beliefs is in Table E-2 and identifies a snapshot of his “operational code”—that is, his state of mind at a particular point in time regarding the exercise of power by Self and Others. It also contains an index of Saddam’s risk orientation regarding interaction with others in the political universe plus his beliefs about risk management tactics and the utility of different forms of political power as means in the pursuit of goals. The analysis in Table E-2 compares Saddam’s beliefs to a sample of world leaders from a variety of historical eras and regions. These scores are expressed in terms of standard deviations from the sample’s average for each belief.6

The results show that Saddam believed that the most effective strategies (I-1 = −1.24) and tactics (I-2 = −1.08) for exercising power were definitely conflictual; however, he was very risk averse (I-3 = −1.71) and controlled the risks of escalation by being extremely flexible in shifting between cooperation and conflict tactics (I-4a = +2.40) and very flexible in shifting between word and deed tactics (I-4b = +1.60) in the exercise of power. He believed that the utility of exercising rewards and punishments was somewhat high (I-5a = +0.40) while the utility of exercising promises (I-5b = −4.67) and threats (I-5e = −3.00) was extremely low. His belief in the utility of opposition and resistance tactics was very high (I-5d = +1.71) while his belief in the utility of appeal and support tactics (I-5a = 0.00) was the same as that of the average world leader (Walker et al., 2003b pp. 388-389).

The VICS indices for I-1, P-1, and P-4 are the basis for constructing a formal model of strategic interaction, which expresses the leader’s definition of the strate-

________________

6 A deviation is the distance between a leader’s score and the average score for the norming group sample. A standard deviation is the distance around the sample mean within which two-thirds of the scores for the entire sample fall. When a leader’s score has a standard deviation above (+) or below (−) the sample mean greater than one standard deviation, it indicates that s/he has a score higher (+) or lower (−) than two-thirds of the sample. The words “Somewhat”, “Definitely”, “Very”, and “Extremely” to describe the standard deviation scores are applied in Table E-2 to half-standard deviation intervals above or below the mean score of the norming group sample for each VICS belief index (see Walker et al., 2003a).

TABLE E-2 The General Operational Code and Subjective Game of Saddam Hussein

| General Operational Code | VICS Indicesa | ||||||||

| Std. Dev | Descriptor | ||||||||

| Philosophical Beliefs | |||||||||

|

P-1 |

Nature of the political universe | −1.47 | Very hostile | ||||||

|

P-2 |

Prospects for realization of political values | −1.33 | Very pessimistic | ||||||

|

P-3 |

Predictability of the political future | −4.67 | Extremely low | ||||||

|

P-4 |

Control over historical development | ||||||||

| a. Other’s control | −3.80 | Extremely low | |||||||

| b. Self’s control | +3.80 | Extremely low | |||||||

|

P-5 |

Role of chance | +4.00 | Extremely high | ||||||

| Instrumental Beliefs | |||||||||

|

I-1 |

Approach to goals | −1.24 | |||||||

|

I-2 |

Pursuit of goals | −1.08 | |||||||

|

I-3 |

Risk orientation | −1.71 | |||||||

|

I-4 |

Timing of action | ||||||||

| a. Flexibility of coop/conf tactics | +2.40 | Extremely high | |||||||

| b. Flexibility of word/deed tactics | +1.60 | Very high | |||||||

|

I-5 |

Utility of means | ||||||||

| a. Reward | +0.40 | Somewhat high | |||||||

| b. Promise | −4.67 | Extremely low | |||||||

| c. Appeal/support | +0.00 | Average | |||||||

| d. Oppose/resist | +1.71 | Very high | |||||||

| e. Threaten | −3.00 | Extremely low | |||||||

| f. Punish | +0.60 | Somewhat high | |||||||

| Saddam’s Subjective Game | US Deter/Assure Game | Intersection of Two Games | |||||||

| Other | US | US | |||||||

| CO | CF | CO | CF | CO | CF | ||||

| CO | 3,2 | 2,4 | CO | 3,4 | 2,3 | CO | 2|0 | 1|0 | |

| Self | Iraq | Iraq | |||||||

| CF | 4,1 | 1,3 | CF | 4,1 | 1,2 | CF | 2|0 | 2|2 | |

| Self Bluff; Other: Bully | Iraq Bluff, US: Deter | Exp|Act Row Outcomesb | |||||||

a VICS indices are expressed as standard deviations above and below the mean for the 20 world leaders.

b Expected versus actual outcome for row player where 0 is upper-left, 1 is upper-right, 2 is lower-right, and 3 is lower-left quadrant of game matrix. Game solutions are in bold.

NOTE: Speeches: n = 6, world leaders: n = 20 from a variety of historical eras and geographical regions.

SOURCE: Adapted from Table 18.1 in Walker et al. (2003b), copyright 2003, courtesy of University of Michigan Press.

gic and tactical situation between Self and Other as a subjective game (Walker et al., 2011). Saddam Hussein’s negative I-1 (−1.24) and negative P-4a (−3.80) valences for Self (Ego) plus his negative P-1 (−1.47) valence and positive P-4 (+3.80) valence for Other (Alter) specify his subjective strategic interaction game as characterized by a Bluff strategy for Self and a Bully strategy for Other.

These strategic orientations for Self and Other in his belief system make it likely that Saddam Hussein will define Other as an adversary rather than an ally, will pursue bluff tactics and increase them to punish, and will use bully tactics to dominate a weaker opponent unless met with firm resistance by an equal or stronger opponent (Schafer and Walker, 2006; Walker et al., 2011). Deterrent and compellent threats are unlikely to be effective unless made by a stronger adversary that has shown firm resolve to carry out the threat in the event of noncompliance. Then he will back down and retreat, as also predicted by Post’s analysis, which documents historical examples of this pattern prior to the 1991 Iraq War (Walker et al., 2003b, pp. 389-390; see also Post, 2003b, pp. 341-342).

The outcome in Table E-2 for playing the bluff strategy assigned to Self and the bully strategy assigned to Other in the Iraqi leader’s subjective game is (CO,CF) domination for Other (US) and submission for Self (IRQ), which Saddam found unacceptable. If US plays a deter/assure strategy instead of a bully strategy against Iraq’s bluffing strategy, the outcome in Table E-2 is either (CO,CO) mutual cooperation or (CO,CF) submission by Iraq and domination by US. If the subjective game for Iraq is Bluff v. Bully and the subjective game for US is Deter versus Bluff and if each plays their own subjective game, then the outcome is always (CO,CO) mutual cooperation with one exception: if the game begins in the lower-right cell (CF,CF) deadlock and Iraq has the next move, then the final outcome is also (CF,CF) deadlock (Walker et al., 2011 Appendix, p. 289).

The examples of Saddam Hussein’s personality traits, motivations, cognitive complexity, operational code beliefs, and subjective game illustrate how content analysis and leadership profiling can provide insights into the psychology of a peer/near-peer, regional, or non-state actor, which reflect a decision unit’s definition of the situation, strategic orientation, and risk-taking propensity in a general, immediate, or extended deterrence situation. Employed with other methods of assessment, such as qualitative cognitive modeling, gaming, and simulations, the convergent validity of the results from any one of these methods can be tested by comparison with the results from the other methods.

There is an extensive store of information in the form of records from past gaming exercises and decision-making processes within those games, which may be re-analyzed with automated content analysis systems to retrieve the personality traits, motives, beliefs, and cognitive styles reflected in these texts attributed to participants in these games (Mintz et al., 1997; Young, 2001; Downes-Martin, 2013). They can reveal more precisely the personality biases at the individual level of the players, which may either reenforce or qualify the external validity of generalizations based on aggregation from individual to larger decision-making units.

Finally, there are also efforts to extend the models, methods, and tools for studying individual leaders to the examination of their social identities and roles in various group, organizational, and societal settings. Some analyses model the

problem of studying larger units of analysis as the study of different forms of leader-advisor systems. They attempt explicitly to model the impact of a leader’s personality on the decision-making dynamics of these systems (Leites, 1951; George, 1980; Winter, 2003b; Kowert, 2002; Hermann and Preston, 1994; Preston, 2001; Hermann, 2003a). The results of these studies in particular may provide the intellectual capital to eventually bridge the present gap between understanding the decisions of individual leaders and various kinds of group decisions in different cultural contexts.

For example, cultural norms and social identities may constrain leaders in recognizing and following the norms of arms control regimes such as the nuclear nonproliferation treaty (NPT). Therefore, it may be difficult for a general deterrence strategy to prevent proliferation of WMD even in the absence of the security threat posited by Realpolitik models as an incentive to acquire them. Cultural forces at work within societies and deeper, nationalist-based norms about what is legitimate and appropriate for countries that aspire to great power or regional power status may over-ride attempts to dissuade states from becoming members of the nuclear club. 7 France’s creation of a nuclear force de frappe under De Gaulle is an example of these forces at work during the Cold War. Iranian aspirations for enhanced regional status in the post-Cold War era is another potential cause of proliferation, in which the outcome of the struggle in this case between going nuclear and limiting further proliferation is uncertain.

These possibilities also support the measurement and analysis of robust reasons and beliefs from historical case studies. It is possible with content analysis and leadership profiling tools to retrieve and model cultural drives and beliefs from real-world decision units as well as from the participants in laboratory gaming simulations and from the idealized decision units assumed by modeling efforts with game theory.

This step is necessary to assess the external validity of results from the hybrid application of abstract modeling and inductive gaming exercises. The external validity question associated with gaming, simulations, experiments, and math modeling efforts is whether the processes and outcomes created in the labora-

________________

7 The literature on norms and behavior is vast. A good discussion of a norms model, a security model, and a domestic/bureaucratic politics model applied to proliferation decisions is Sagan (1996-1997). An extension of this discussion with case studies of Iraq, China, Yugoslavia, and Argentina is contained in Hymans (2012). Discussions of the insights from models based on, respectively, social identities, status positions and belief systems are Hymans (2006), Larson and Shevchenko (2010), and O’Reilly (2012). A provocative treatment of the issues surrounding the creation and maintenance of international norms and nonproliferation regimes (nuclear, chemical, and biological) is in Joyner (2009). An excellent analysis of the motivations of small states to acquire WMD is in Preston (2007). An important comparative theoretical analysis of the operation of cultural norms in the international relations of different civilizations is contained in Lebow (2008).

tory simulations or math modeling exercises correspond to the behavior of actual decision-making units in the political world.8

CONCLUSION

Deterrence is at heart a psychological concept, resting on understanding the psychology of the deteree—for example, if the deteree is a non-state terrorist group seeking martyrdom, the threat of death will be taken as an incentive rather than a deterrent. Therefore, evaluation of proposals for deterrence and assurance must rest on a nuanced understanding of the mindset and decision-making of the adversary or ally whenever possible. In contrast to during the Cold War era, when the Soviet Union was the main source of a strategic threat to the United States, in the 21st century it is necessary to have an accurate understanding of the leadership styles and decision-making processes of a broad spectrum of dangerous adversaries and a proliferation of threats from very different sources. One can neither effectively and efficiently deter with a threat nor assure with a promise an adversary or ally that one does not understand.

The tools of content analysis and leadership profiling in conjunction with other methods and tools have the potential to meet the requirements of actor-specific knowledge for a strategy of tailored deterrence. An alliance of content analysis, leadership profiling, abstract modeling, gaming, and simulations as a suite of methods and tools is possible in order to solve the complex problems associated with studying the decision-making dynamics of single groups and multiple autonomous actors as decision units.

REFERENCES

Allison, G., and P. Zelikow. 1999. Essence of Decision, 2nd ed. Longman, New York.

Brands, H., and D. Palkki. 2012. Conspiring bastards: Saddam Hussein’s strategic view of the United States. Diplomatic History 36:625-659.

Brecher, M., and J. Wilkenfeld. 2000. A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

________________

8 In a recent review, Downes-Martin (2013) concluded that war games, models and simulations in think tanks and planning cells used to plan strategic deterrence face two problems. The decisions predicted by participants for themselves and the leaders to be deterred are most likely inaccurate; decisions made or implied during precrisis war games are poor proxies for the decisions that will actually occur, even if the evolving situation is accurately predicted. However, cultural drives and, especially, beliefs are remarkably robust, even in the face of proven and credible contradictory evidence. Downes-Martin concludes that war games to address nuclear deterrence problems are more likely to provide credible results under the following conditions: (1) when the focus is on reasons for decisions made and predicted, not the decisions themselves; (2) the focus is on messages sent, and reasons for their (mis)interpretation; (3) the focus is on the beliefs of the players (planners) as well as the beliefs of the players; (4) the focus is on embedding these reasons into the models and simulations.

Davis, P., and J. Arquilla. 1991. Thinking about opponent behavior in crisis and conflict. RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

De Rivera, J. 1968. The Psychological Dimension of Foreign Policy. Charles E. Merrill, Columbus, Ohio.

Downes-Martin, S. 2013. Adjudication: The diabolus in machina of war gaming. Naval War College Review 66:67-81.

Downs, G. 1989. The rational deterrence debate. World Politics 41:225-237.

Ellsberg, D. 1961. The crude analysis of strategic choices. American Economic Review 51:472-478.

Fearon, J. 1994a Domestic political audiences and the escalation of international disputes. American Political Science Review 88:577-592.

Fearon, J. 1994b. Signaling vs. the balance of power and interests: an empirical test of a crisis bargaining model. Journal of Conflict Resolution 38:236-269.

Fiske, S., and S. Taylor. 1991. Social Cognition. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Freedman, L., and E. Karsh. 1993. The Gulf Conflict, 1990-1991. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Funk, C., K. Smith, J. Alford, M. Hibbing, N. Eaton, R. Krueger, L. Eaves, and J. Hibbing. 2013. Genetic and environmental transmission of political orientations. Political Psychology 34:805-820.

George, A. 1980. Presidential Decision Making in Foreign Policy. Westview, Boulder, Colo.

Geva, N., and A. Mintz. 1997. Decisionmaking on War and Peace. Lynne Reiner, Boulder, Colo.

Glaser, C. 2010. Rational Theory of Politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Greenstein, F., and M. Lerner. 1971. A Source Book for the Study of Personality and Politics. Markham, Chicago, Ill.

Hermann, C. 1969. International Crises. Free Press, New York.

Hermann, C., ed. 1972. International Crisis. Free Press, New York.

Hermann, M. 2003a. Assessing leadership style: Trait analysis. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Hermann, M. 2003b. Saddam Hussein’s Leadership Style. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Hermann, M., and T. Preston. 1994. Presidential advisors and foreign policy. Political Psychology 15:75-96.

Holsti, O. 1972. Time, alternatives, and communications: The 1914 and Cuban Missile Crises. In International Crises (C. Hermann, ed.). Free Press, New York.

Holsti, O., R. North, and R. Brody. 1968. Perception and action in the 1914 crisis. In Quantitative International Politics (J.D. Singer, ed.). Free Press, New York.

Hymans, J. 2006. The Psychology of Nuclear Proliferation: Identity, Emotions, and Foreign Policy. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Hymans, J. 2012. Achieving Nuclear Ambitions: Scientists, Politicians and Proliferation. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Jervis, R. 1976. Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Joyner, D. 2009. International Law and the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction. Oxford University Press, New York.

Kowert, P. 2002. Groupthink or Deadlock? SUNY Press, Albany, N.Y.

Larson, D. 1985. Origins of Containment. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Larson, D., and A. Shevchenko. 2010. Status seekers: Chinese and Russian responses to U.S. primacy. International Security 34:63-96.

Lebow, R. 2008. A Cultural Theory of International Relations. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Leites, N. 1951. The Operational Code of the Politburo. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Marcus, G. 2003. The psychology of emotion in politics. In The Handbook of Political Psychology (D. Sears, L. Huddy, and R. Jervis, eds.). Oxford University Press, New York.

Mintz, A., N. Geva, S. Redd, and A. Carnes. 1997. The effect of dynamic and static choice sets on political decision making. American Political Science Review 91:553-566.

Morgan, P. 2003. Deterrence Now. Cambridge University, New York.

Neuman, W., G. Marcus, A.C Rigler, and M. Mackuen, eds. 2007. The Affect Effect. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill.

Neustadt, R., and E. May. 1986. Thinking in Time: The Uses of History for Decision Makers. Free Press, New York.

O’Reilly, K. 2012. Leaders’ perceptions and nuclear proliferation. Political Psychology 33:767-789.

Post, J. 2003a. The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Post, J. 2003b. Saddam Hussein of Iraq: A political psychology profile. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Preston, T. 2001. The President and His Inner Circle. Columbia University Press, New York.

Preston, T. 2007. From Lambs to Lions: Future Security Relationships in a World of Biological and Nuclear Weapons. Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, Md.

Robbins, E., H. Hustus, and J. Blackwell. 2013. Mathematical foundations of strategic deterrence. In Thinking About Deterrence (A. Lowther, ed.). Air University Press, Maxwell, Ala.

Sagan, S. 1996-1997. Why do states build nuclear weapons? Three models in search of a bomb. International Security 21(Winter):54-86.

Schafer, M., and Crichlow, S. 2010. Groupthink v. High-Quality Decision Making in International Relations. Columbia, New York.

Schafer, M., and S. Walker, eds. 2006. Beliefs and Leadership in World Politics. Palgrave, New York.

Schneider, B. 2012. Deterrence and Saddam Hussein: Lessons from the 1990-1991 Gulf War. In Tailored Deterrence, 2nd ed. (B. Schneider and P. Ellis, eds.). USAF Counterproliferation Center, Maxwell, Ala.

Shannon, C., and W. Weaver. 1964. The Mathematical Model of Communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Ill.

Simon, H. 1985. Human nature and politics. American Political Science Review 79:293-304.

Smith, M. 1968. A map for the study of personality and politics. Journal of Social Issues 24:15-28.

Stein, J. 1991. Deterrence and compellence in the Persian gulf. International Security 17:147-179.

Steinberg, B. 1996. Shame and Humiliation: Presidential Decision Making on Vietnam. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Suedfeld, P. 2003. Saddam Hussein’s integrative complexity under stress. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Suedfeld, P., K. Guttieri, and P. Tetlock. 2003. Assessing integrative complexity at a distance. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

‘t Hart, P., E. Stern, and B. Sundelius. 1997. Beyond Groupthink. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Vertzberger, Y. 1990. The World in Their Minds. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif.

Walker, S. 2013. Role Theory and the Cognitive Architecture of British Appeasment Decisions. Routledge, New York.

Walker, S., M. Schafer, and M. Young. 2003a. Profiling the operational codes of political leaders. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Walker, S., M. Schafer, and M. Young. 2003b. Saddam Hussein: Operational code beliefs and object appraisal. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Walker, S., A. Malici, and M. Schafer. 2011. Rethinking Foreign Policy Analysis. Routledge, New York.

Winter, D. 2003a. Measuring the motives of political actors at a distance. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Winter, D. 2003b. Saddam Hussein: Motivations and mediation of self-other relationships. In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (J. Post, ed.). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Woods, K., and M. Stout. 2010. Saddam’s perceptions and misperceptions: The case of ‘Desert Storm.’ Journal of Strategic Studies 33:5-41.

Young, M. 2001. Building worldviews with profiler+. In Progress in Communications Sciences (C. Barnett, ed.). Ablex Publishing, Westport, Conn.

Zagare, F., and M. Kilgore. 2000. Perfect Deterrence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

Zajonc, R. 1980. Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist 35:151-175.

Zinnes, D. 1968. The expression and perception of hostility in crisis: 1914. In Quantitative International Politics (J.D. Singer, ed.). Free Press, New York.