Analytic Issues and Factors Affecting Deterrence and Assurance

This chapter, which responds to Item 1 in the terms of reference (TOR), highlights key analytic issues, questions, and challenges that arise in attempting to deter adversaries and assure allies. It also provides definitions and sets the stage for discussions of analytic approaches in Chapter 3.

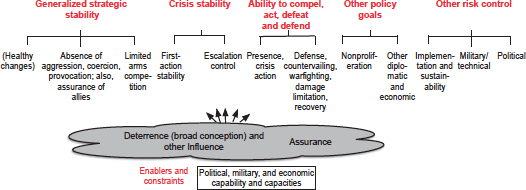

The word deterrence is often used as shorthand for a set of complex matters.1Figure 2-1 draws on classic strategic thinking to infer a set of de facto objectives for U.S. strategic planning including nuclear and other forces.2 These objectives include (1) a generalized strategic stability that includes healthy change without aggression or arms races; (2) crisis stability; (3) the ability of the United States to act militarily as necessary in peacetime and in crisis, and, in the event of war, to fight effectively and limit damage to the United States, its allies, and other interests; (4) nonproliferation and other policy goals; and (5) other kinds of risk control such as those relating to the implementation of strategy, military-technical risks, and political

________________

1 See National Research Council (1997), chaired by GEN Andrew Goodpaster (U.S. Army [USA], retired) for related discussion.

2 The objectives are drawn or inferred from such classic deterrence literature as Kahn (1960), Schelling (1960, 1966), and Morgan (1983, 2003) and from statements of senior officials (Schlesinger, 1974a,b; Brown, 1981; Slocombe, 1981; Brown, 1983; Department of Defense (2010c, 2014). The figure builds on Davis (2011). Other objectives are implicit, such as shaping the postcrisis and postconflict environments.

FIGURE 2-1 Objectives in strategic planning that includes nuclear forces. SOURCE: Adapted from Davis (2011), with permission by the RAND Corporation.

risks. Casual reference to the U.S. objective of deterrence, then, often involves much more than deterrence per se. A sharpened discussion requires tighter definitions.

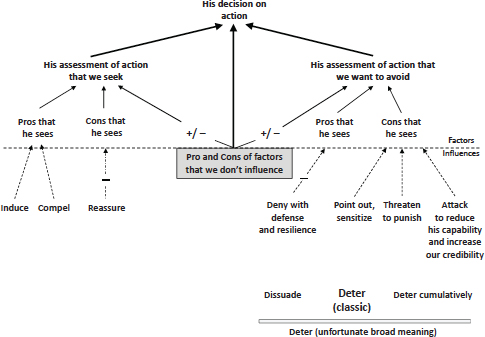

Figure 2-2 illustrates a number of distinctions and subtleties that are reflected in the definitions listed in Table 2-1. The figure shows the adversary comparing two options (top), of which we prefer the one on the left (that might be “no action”) and seek strongly to avoid the one on the right. It is common to refer to trying to “deter” the adversary from the decision on the right, but the adversary’s behavior will actually depend on quite a number of considerations.

The adversary perceives pros and cons to each action, and we may affect those perceptions by various influences (red dotted items), including deterrence.3 Our influences attempt to increase the attractiveness of the preferred option and to decrease (see the negative signs in the figure) the attractiveness of the option to be avoided. The adversary’s decision, however, is subject also to factors that one cannot easily influence, such as his internal politics, nationalism, pride, and rationality.

Influences other than normal deterrence by threat of punishment include inducements or reassurances to an adversary who fears attack; coercive threats or actions to compel action; dissuasion by being able to deny an adversary’s success

________________

3 Seeing deterrence as one element of influence is discussed in Davis and Jenkins (2002) and George (2003). See also George and Smoke (1974).

FIGURE 2-2 Relationships among concepts. SOURCE: Davis (2014a), reprinted with permission by the RAND Corporation.

with defense or resilience or by helping an adversary recognize courses of action more in the adversary’s interest; and punishments for past actions to improve future deterrence—that is, to improve “cumulative deterrence.”4 Discussions sometimes use “deterrence” to refer, with regrettable looseness, to a combination of dissuasion, classic deterrence, and cumulative deterrence. The report recognizes this (bottom right of figure) with the umbrella term “broad deterrence” but attempts to be more specific in the related discussion.

With this background, Table 2-1 shows the key definitions used in this study. Two final observations are significant: (1) deterrent actions may or may not have much effect in “causing” the adversary’s subsequent behavior because of the multiple influences at work simultaneously and (2) actions taken to deter may have unintended side effects, sometimes the opposite of those intended, as when a side’s efforts to deter are seen as aggressive and reckless.

________________

4 Had the United States attacked Syria in 2013, it would have been to “punish now” so as to deter further use of chemical weapons.

TABLE 2-1 Definitions

|

|

|

|

Term |

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

Influence |

Effects on the decisions of another party by, for example, positive inducements, persuasion, dissuasion, deterrence, compellence, and punishment.a |

|

General deterrence |

Deterrence over time in periods of peace. If successful, it will head off crises in which immediate deterrence would be at issue. |

|

Deterrence (classic) |

Convincing an adversary not to take an action by threatening punishment only if the action is taken but not otherwise [see also “broad deterrence,” below]. |

|

Dissuasion by denial (often called deterrence by denial) |

Convincing an adversary not to take an action by having the perceived capability to prevent success adequate justify the costs.b |

|

Cumulative deterrence |

The quality of deterrence at a given time due to the history of prior successful and failed deterrent actions, crises, and conflicts.c |

|

Broad deterrence |

A combination of the previous three. |

|

Direct deterrence |

Deterring an attack on the United States or its immediate interests. Direct deterrence is more likely to succeed than extended deterrence (see below), because the deterrent threat is inherently more credible. |

|

Extended deterrence |

Convincing an adversary not to take an action against the interests of an ally by the methods of broad deterrence. |

|

Dissuasion |

Persuading an actor (such as an adversary) from taking a particular action. |

|

Compellence |

Causing an actor (such as an adversary) to take an action despite its preferences to the contrary, by using or threatening to use military, economic, or political power. |

|

Coercion |

Causing an actor unwillingly to do something by use of force or threat. Deterrence and compellence are different kinds of coercion. |

|

Assurance |

Convincing an ally of U.S. commitment to and capability for extended deterrence for the purpose of dissuading the ally from developing its own nuclear arsenal. |

|

Reassurance |

Reducing fears of potential adversaries regarding U.S. intentions or the intentions of U.S. allies. |

|

|

|

a See George and Smoke (1974), Davis and Jenkins (2002), and George (2003).

b We adjust the concept of deterrence by denial (Snyder, 1961) by expressing it as dissuasion based on adversary perceptions of potential gains and losses (Davis, 2014b). See also Waltz (1990) and Sawyer (forthcoming).

c Cumulative deterrence is important in Israeli strategy (Doron, 2004; Rid, 2012; Adamsky, forthcoming). It overlaps with the credibility component of deterrence but reflects the history of events that also affect psychological appreciation of and distaste for what the punishment would mean. That is, it affects perceived consequences and saliency.

Deterrence and assurance contribute to several higher-level objectives, as indicated by the gray cloud in Figure 2-1. The objectives referring to defense, countervailing, war fighting, and damage limitation may seem more appropriate to Cold War days than to now. However, they remain enduring objectives that are applicable in many military situations. They also apply when deterrence fails. Even if objectives are agreed, how best to build and employ nuclear forces has always been controversial. Presidents have long insisted on employment flexibility, complaining about the narrowness of options provided to them in operations plans. They have been concerned both about the immorality of indiscriminate use and about how overly blunt options undercut the credibility that the United States would use nuclear forces if it had to. Having no option other than Armageddon is, arguably, to have no option.5

As a result of such concerns, limited nuclear options were emphasized as part of flexible-response strategy, and by the end of the 1970s and after extensive analysis across three administrations, the United States settled on an even broader “countervailing strategy.” The term countervailing was a nuance: Although assumptions about warfighting and war winning seem to lose meaning in scenarios involving massive nuclear exchanges, the United States wanted to assure that any Soviet leaders would conclude that no nuclear warfighting strategy could lead to meaningful victory and that the price would be too high.

Why is this relevant today when the Cold War is so long gone? The core reason is that the imperative to avoid nuclear war at all costs is not now, nor has it been, an inviolate and universally accepted principle of nature. During the Cold War, both the Soviet Union and the United States regarded nuclear weapons as valuable for coercive diplomacy.6 They also developed first-nuclear-use options for scenarios that were deemed conceivable.7 The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) developed and practiced operational doctrine for initiating nuclear use as needed to re-establish deterrence in the event of a Warsaw Pact invasion that could not be defeated with conventional forces. Despite an ostensible no-first-use policy, the Soviets had war plans for massive first use, which they characterized as preemptive.

________________

5 See Burr (2005) for archival data, including Henry Kissinger’s comment that “To have the only option that of killing 80 million people is the height of immorality.” The comment reflected President Nixon’s strong discontent with the options provided him. He found the all-or-nothing options appalling and, according to an interpretation of a comment by Henry Kissinger, expressed unwillingness to order the war plan’s execution (Mastny et al., 2013, p. 121).

6 See Delpech (2012, pp. 61-80) for a comprehensive review.

7 See a recent review (Long, 2008).

Finally, during the Cuban missile crisis, Fidel Castro had urged the Soviet Union to use nuclear weapons if Cuba was invaded, even though he presumably knew it would lead to the destruction of Cuba.8 We now we know that the world was lucky to have escaped that crisis.9,10

Today, Russia regards nuclear weapons as a core element of its ability to deter China and NATO from nuclear or conventional attack11 and has well-developed options for using them on the battlefield and geo-strategically with escalation control as a centerpiece. Pakistan regards nuclear weapons as a key to deterring a conventionally dominant India. Its programs appear to include tactical nuclear weapons, and its planning presumably includes preparing for at least limited nuclear warfighting.12 Although Indian nuclear policy is ambiguous, Indian officials have spoken of being at liberty to use conventional force given their nuclear capability. Additional observations could be made regarding Israeli, North Korean, British, and French perspectives. The overall point is that nuclear weapons have played an important role in nations’ foreign policies for a number of different reasons: Nuclear weapons have on occasion been considered usable, even when the condi-

________________

8 Castro apparently saw the potential invasion of Cuba in apocalyptic terms, an attack of “Imperialism on Socialism.” In a telegram to Khrushchev, he appeared to urge a nuclear strike on the United States in the event of such an invasion. See Garthoff (1992) and the original telegram at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/114501.

9 See Nathan (1992), Fursenko and Naftali (1997), Dobbs (2008), and Kokoshin (2012).

10 Robert McNamara once said

Had Khrushchev not announced publicly on the 28th of October—a Sunday—that he was removing the missiles, I believe that on Monday the majority of President Kennedy’s military and civilian advisers would have strongly urged air attacks, with the likelihood of a sea and land invasion …. Some of us thought then the risks were very, very great. We underestimated them. We didn’t learn until nearly 30 years later, that the Soviets had roughly 162 nuclear warheads on this isle of Cuba, at a time when our CIA said they believed there were none…. Had we … attacked Cuba and invaded Cuba at the time, we almost surely would have been involved in nuclear war.

(National Archives Project, undated).

11 According to Russian scholars (Arbvatov and Dvorkin, 2013, p. 16), the official Russian statement is that

the Russian Federation reserves the right to use nuclear weapons in response to the utilization of nuclear and other types of weapons of mass destruction against it and (or) its allies and also in the event of aggression against the Russian Federation involving the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is under threat.

12 See Khan (2005). Feroz Khan, a Pakistani, was writing while serving as a visiting fellow at the Stimson Center and has since written on the history of the Pakistani bomb (Khan, 2012).

tions of mutual assured destruction exist, and nuclear weapons have been “brandished” as part of strategic communication.13 There has never been a clean break between deterrence and warfighting, or between counterforce and countervalue attacks. Scenario details have matured and likely will continue to matter greatly. To reiterate, and despite successes in establishing international nonproliferation regimes and pressures in some areas of the world to eliminate nuclear weapons altogether, it is likely that some countries in some circumstances will in the future have powerful incentives for using or credibly threatening to use them.

What Do Nuclear Forces Help to Deter?

One of the most important contributions of nuclear strategic thinking in the 20th century was recognizing how the deterrent challenge varies with circumstances. Myriad scenarios should be considered, with certain distinctions being particularly important: (1) extended versus immediate deterrence; (2) direct versus extended deterrence; (3) deterring nuclear attacks versus deterring conventional attacks; (4) deterring small rather than large attacks; (5) deterrence before, during, or after war; and (6) deterring different countries or leaders (i.e., personalities, cultures, and mindsets matter).

What about today? Is the only significant role of U.S. nuclear forces to deter an adversary’s use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), as some believe? Or, do nuclear weapons have a continuing, albeit less direct role to play in deterring conventional aggression against U.S. allies by creating a “shadow”? The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) takes a view somewhere in the middle, observing that the role of nuclear weapons in deterring conventional, chemical, or biological aggression continues but has declined.14 Most recently, some have argued—quite controversially—that deterrence should also extend to preventing high-end versions of cyberwar—that is, cyberattacks so broad and destructive as to have massively destructive effects analogous in some respects to nuclear war. 15,16

In fact, all extensions of scope beyond deterring use of nuclear weapons continue to be controversial. One view is that the other classes of attack are in a lesser league and can be deterred or countered without resort to nuclear weapons. Another view is that the most destructive but not-implausible versions of biological attack especially would be catastrophic. The Soviet Union had a massive biological

________________

13 See Bracken (2012) and Delpech (2012).

14 See Department of Defense (2010b, p. 15).

15 The report interprets “existential deterrence” as “deterrence due to fear of attack so catastrophic as to make details of both pre- and postconflict power balances irrelevant.” To some, referring to existential deterrence is “getting real.” To others, it seems like a cessation of critical thinking.

16 See Defense Science Board (2013b) and rejoinders (Clarke and Steve, 2013; Colby, 2013).

warfare program,17 Iraq pursued biological capabilities under Saddam Hussein (Zilinskas, 2000), and North Korea may have biological weapons (Bennett, 2013). Such weapons are extremely lethal.18 It is well to note here that heuristics such as “nuclear weapons only deter nuclear use” are examples of how people have sought to categorize weapons neatly. If history is a guide, however, nations, regimes, and commanders will not respect categorical boundaries, especially if stakes are high enough.

What Should Be the Basis of Nuclear Employment Planning?

Modern discussion of nuclear matters, including possible reductions to very small numbers or even to zero, typically does not address what operational nuclear planning should focus on—even if merely deterrent options that, presumably, would never be triggered. The question is this:

If deterrence requires credibility and if credibility requires operational capability, then employment planning is necessary. But what should the targets be and what capabilities are needed?

Perhaps some, such as proponents of depending solely on “existential deterrence,” would argue that it is only “arsenals” that must be kept “safe, secure, and effective,” without need for ready forces or ready-to-implement targeting plans. Even if this is so, it would be necessary that forces could be brought to high readiness quickly and that actual operational targeting could be decided at the time (with some preplanning). For that to be viable, however, the substantial background work, training, and development of alternative targeting plans would still have to deal with the same issues faced by U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) today. Thus, the question cannot be avoided: What should be targeted by nuclear weapons and what does this imply for planning and operations?

The targeting question might be addressed from diverse perspectives. Some observations are as follows:

1. Despite the precedents in the Second World War that included carpet bombing, fire bombing, and atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, attacking population centers raises enormous moral and legal concerns, even if the attacks are nominally on collocated industry.

________________

17 See Leitenberg et al. (2012) and Albeck and Handelman (1999).

18 See Lederberg (1999). Terrorist attacks are of special concern, although the application of nuclear deterrence is unclear in such scenarios and higher priority should probably be given to preparing defenses and adaptations (Danzig, 2009).

2. Further, such an attack would virtually guarantee a response in kind, if possible. Thus, would such an attack merely be part of mutual suicide? If so, how could the capability for such an attack provide credible deterrence?

3. Continuing from (2), would such capability be credible for deterrence? Strategists have been extremely doubtful since the 1950s.

4. By analogy with armies attacking armies rather than razing cities (something usually regarded as a momentous advance in civilization’s norms), shouldn’t nuclear targeting focus on threat, notably nuclear and comparably threatening systems rather than innocent civilians?

5. Alternatively, if the counter-nuclear-threat targeting is too difficult, shouldn’t nuclear targeting focus on other military targets with the intent of crippling the ability of the target state to project force or maintain authoritarian control?

6. If presented with the need to actually employ nuclear weapons, wouldn’t any U.S. President seek very limited options—for example, destroying a class of adversary forces or weapons, blunting an invasion, or demonstrating ruthless resolve?

It is not the purpose of this report to resolve these weighty issues but rather to lay them out candidly because they bear heavily on nuclear analysis and the methods that should be brought to bear in such analysis.

What Are the Key Principles for Thinking About Assurance?

Although mostly focused on deterrence, this study considers assurance issues at every stage. The committee heard directly from officials and officers who are intimately involved in related work.19 Many of the methods used to evaluate military issues and the quality of deterrence can be applied to questions of assurance and even shared or conducted with partners (for example, studies, analyses, and political–military gaming) as part of assurance activities.

The committee did not identify a separate class of “assurance methods,” and it is difficult even to characterize a framework or theory for this quintessentially diplomatic activity. Nonetheless, the following can be considered as contributing principles.20

1. Even at its simplest, assurance is complex. Even if deterrence is in fact strong, assurance can be demanding. Diplomats often claim that achieving assurance is

________________

19 This included a session with Bradley Roberts, until recently the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, an earlier briefing by David Stein, Office of the Secretary of Defense (Policy), and an information-gathering session at U.S. STRATCOM in Omaha.

20 This discussion draws in part on unpublished work by Ely Ratner for an earlier STRATCOM-sponsored study, on Wheeler (2010), and—for the last item—on Crawford (2003), which discusses “pivotal deterrence.”

more difficult than deterrence itself because it involves building—and sustaining—trust and confidence among people, organizations, and countries.

2. There is no single definition of “credibility.” Allies are not likely to assess credibility in the same way as the United States. U.S. reasoning often revolves around shared interests, U.S. capability, formal agreements, policy, and intent. Affected allies are rationally sensitive as well to how a nation’s commitments may become slippery when fulfilling them becomes too risky or costly. The degree of assurance that can be achieved, then, is inextricably related to the credibility of extended deterrence.

3. Assurance can have negative side effects. It is possible for efforts taken in the name of assurance to encourage allies to take courses of action contrary to U.S. interests (and perhaps to the ultimate interests of the ally). This is why U.S. assurances have long been deliberately ambiguous on matters relating to China and Taiwan.

4. Assurance involves all forms of national power. U.S. success in assurance efforts often depend as much or more on its capability for coercive diplomacy as on its capability to deter. The strength of a security relationship depends, after all, not just on deterring particular actions but also on its effectiveness in influencing events more generally, sometimes coercively.

5. What assures changes? Assurance success in the current era depends on the United States being seen as successfully adapting to shifting power alignments in ways acceptable to the security partners. This issue is prominent not only in the Asia-Pacific region but also in the Middle East and along the borders of the former Soviet Union.21

The Department of Defense (DoD) is sensitive to these issues and has strived to engage officials and military officers from key countries—with site visits and in-depth discussions, not just exchanges of policy statements. One recurring issue is that influential allied representatives often see great value in forward-deployed systems, including nuclear-capable systems. Such deployments may not seem necessary or appealing to Americans given the demonstrated ability to fly long-distance missions and to redeploy forces if necessary, but they are seen as significantly improving the credibility of the U.S. commitment.

WHAT IS NEW IN THINKING ABOUT DETERRENCE AND ASSURANCE?

The preceding material was largely general. The following sections describe what is new about the current era and what has been learned from the past.

________________

21 See, for example, Research Group on the Japan–U.S. Alliance (2009).

Thomas Schelling (2012) wrote recently about the success of mutual deterrence between the Warsaw Pact and NATO but then observed

What a simple thing that was, that bilateral mutual relationship! Just two parties, fully identified, sophisticated and “rational,” fully reciprocal, with nothing at stake worth a war, no real territorial threats, at least after 1962, no great technological secrets, good diplomatic communication, especially after the “hotline” of 1963.

Schelling went on to discuss differences today. For the particular book, he was stressing issues raised by the terrorist threat, but many of the differences were more general, such as multiple adversaries, multiple motives, poor communications, no collaboration, no confidence in taboos, and no confidence in “rationality.” To be sure, almost nothing is truly new for deterrence theory in that antecedents can usually be found. Nonetheless, as Table 2-2 suggests, some important differences of degree exist and some issues are indeed new. 22 One consequence of change is that it is now more necessary to study the possibilities of very limited nuclear exchanges and limited nuclear war. During the Cold War, the overwhelming emphasis was on general nuclear war (despite the attention to NATO’s flexible response).

Have the Right Lessons Been Learned from the Past?

The lessons some draw from the Cold War are often dubious. It is sometimes argued, explicitly or implicitly, that (1) nuclear weapons are useful only for deterring use of nuclear weapons; (2) that deterrence in the Cold War ultimately came down to nothing more complicated than existential deterrence, which could be achieved with very few nuclear weapons; (3) that defenses are ineffective because the offense-defense competition favors the offense; and that (4) a Third World War was averted because of rational behavior under the reality (rather than the strategy) of mutual assured destruction. The first argument is false; the second is widely (but not unanimously) believed by experienced strategists to be false; the third reflects a judgment that was arguably valid at certain points in history but may not be true now or in the future; and the fourth argument gives only part of the story since the objective motivations for war between the Soviet Union and West were low in historical terms.

________________

22 Keith Payne makes similar points (Payne, 2008, p. 205 ff.), drawing contrasts with the Cold War, during which the United States and the Soviet Union had strong reasons for avoiding conflict. See also Davis and Jenkins (2002) and Lowther (2013), a recent book on deterrence from the Air War College. For discussion of technological issues, see Lehman (2013) in a recent book on strategic stability (Colby and Gerson, 2013).

TABLE 2-2 What Is New or Different?

|

|

|

| Class of Issue | Changed Circumstance |

|

|

|

| Actors | More nuclear-weapon or nuclear-capable states, and bigger arsenals. Violent extremist organizations that may not be deterrable in the same manner as nation-states. |

|

Strategic context |

Potential for n-party arms races. |

|

Weapons and technology |

Long-range precision conventional weapons for strategic attack. Dependence of modern nations on space systems and worldwide networking disruptable by physical attack or cyberwar. |

|

|

Implications of modern science for biological warfare. Accelerated advances and spread of strategic technologies. The expectation of future technologies that may alter basics such as how we think about command and control, air and missile defense, antisubmarine warfare, and survivability against nonnuclear forces. |

|

|

|

What, then, are the better lessons? Some were stimulated by top-level war-gaming in the Reagan administration (Bracken, 2012). Although war games usually did not cross the nuclear threshold because of political sensitivities and the fact that such use would be a game-stopper interfering with other game objectives, the Proud Prophet exercise resulted in general nuclear war growing out of the “seemingly inexorable consequences of nations and organizations implementing their own strategies and doctrine” (Bracken, 2012, pp. 84-89). Bracken believes the exercise had a major, lasting, and sobering influence on the thinking of top officials.

Similar lessons have been drawn over the years stem from the RAND Corporation’s “Day After Exercises” and from political–military war games at the Naval War College and elsewhere. Protagonists (often senior civilians and military officers) routinely “brandish” nuclear weapons ambiguously without intending to use. Misperceptions and miscalculations are common, with both acts of resolve and demonstrations of restraint having unintended results; the most important risks are sometimes ignored until too late, and participants take escalatory actions that might naively have been thought “unthinkable.” Other sources of lessons include historical case studies (see Chapter 3) and often-candid reflections by past practitioners of nuclear strategy.23 A “meta lesson” for today is that those working on deterrence and assurance should draw on diverse sources of knowledge.

________________

23 See Quinlan (2009), Delpech (2012), and observations made in various venues by former Secretaries of Defense James Schlesinger and Harold Brown. The committee received a briefing on such reflections by Larry Welch, a former Chief of Staff of the Air Force and president of the Institute for Defense Analyses. See also two recent studies (Utgoff and Wheeler, 2013; Coe and Utgoff, 2008).

TABLE 2-3 Selected Focus Issues

|

|

|

| Category | Theme |

|

|

|

|

Understanding deterrence and influence in modern contexts |

Increased importance of general deterrence and cumulative deterrence. Need to improve and move beyond rational-actor assumptions. More complex regional/escalatory dynamics. The role of dissuasion by denial. |

|

|

|

|

Planning and analysis |

Dealing with expanded uncertainty. The relationship between defense and assurance. Anticipating the unexpected, geopolitically and technologically. |

|

|

|

|

Attending to basics |

Maintaining safe, secure, and effective forces. |

|

|

|

WHAT ISSUES SHOULD ANALYSIS ADDRESS?

A core task for this study is identifying which issues involving nuclear forces should be of concern, which questions should be addressed analytically, and which methods of analysis might help. The following describes selected issues that appear to merit special attention and have significant implications for the discussion of analytic methods in Chapter 3. The themes fall into groups as indicated in Table 2-3: (1) understanding deterrence and influence in the modern context, (2) planning and analysis for future forces and operations, and (3) attending to basics. They are discussed in turn.

Increased Importance of General Deterrence

General deterrence—that is, peacetime efforts to deter conflict—is especially important because, if successful, it will head off what otherwise could become crises: events that are notoriously difficult to control. It is better for the states in question to avoid actions that take matters into potential danger zones than to plan on cleverly navigating the shoals of near-crisis situations.24 The potential for “small” events to have large impact is worrisome.25 Part of what is needed are called “rules of the road” that govern normal and crisis-time military operations and that can avoid or mitigate the escalatory consequences of more militarily conservative doctrine.

________________

24 See Morgan (1983, 2003).

25 Davis and Wilson (2011) note the possibility of troublesome actions in East Asia such as preemptive island grabs or “incidents” on the high seas. See Colby and Ratner (2014) for arguments about the need for the United States to be more assertive.

Observation 2-1. Norms of Behavior. Because of the escalatory potential of even smallish conflicts, “rules of the road” are vague in important areas such as cyberspace, outer space, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Asia. Better ones are needed.

As an example, when U.S. naval ships were operating recently near the early operations of a new Chinese carrier and its escorts, China maneuvered a warship in such a way as to nearly cause collision with a U.S. missile ship. As for cyberspace, it seems evident that the technology for aggressive actions has proceeded faster than the understanding of likely and potential consequences. The most well-known example involves the Stuxnet worm (Sanger, 2012), which had temporary effects of the sort intended, but which also had subsequent unintended effects broadly. Most recently (Spring 2014), related problems arose as Russia absorbed Crimea and threatened the rest of Ukraine.

While confidence-building measures and rules of the road can have undesirable or unintended consequences, recognized norms of behavior that encourage restraint can be useful. Improving general deterrence and related rules of the road will necessarily involve government-wide discussions, government-to-government negotiations, and military-to-military interactions. However, it should be noted that developing well-understood international norms (rules of the road) favorable to the United States depends on the national leaders of the countries in question seeing some value in more restrained, cautious interactions. That condition may or may not apply to China and Russia in what they think of as their natural spheres of influence.

Improving and Moving Beyond Rational-Actor Assumptions

The dominant paradigm for theoretical discussion of deterrence and even for codification of concepts in doctrine is that of rational-actor decision making. In this paradigm, one deters by convincing the adversary that the risks of the action to be deterred outweigh the benefits, compared to inaction. The degree to which the paradigm relies on the rational-actor model can be seen in the terminology, which refers to affecting the adversary’s “calculus.”26 This paradigm can be powerful when the emphasis is placed on the adversary’s reasoning and conclusions, which in turn are affected by the adversary’s objectives, values, and perceptions. It can even anticipate and explain seemingly irrational behaviors such as suicide bombing by terrorists by understanding martyrdom in behalf of a people, cause, or god. That requires extending the rational-actor calculus to go beyond materialistic values

________________

26 This concept can be found in multiple scholarly and official sources (USSTRATCOM, 2006). The committee was briefed on interpretations by Jonathan Drexel and Lt Gen Robert Elder (USAF, Ret.).

and allow for, for example, nationalism, identity, religious convictions, honor, and self respect.27,28 Substantial success has also been reported in the ability to use rational-actor theory to predict political maneuverings and eventual compromise in organizations and foreign affairs involving multiple actors.29

Although rational-actor approaches can, then, be improved, there are also limitations because people do not always behave rationally and because, even if they do, their reasoning may not be understood. There is a long history of trying to get into the adversary’s head when contemplating deterrence, although the history of efforts to do so has been decidedly mixed. Fortunately, deterrence can sometimes work against adversaries whose reasoning is not understood.

Even with good attempts to understand the adversary, the rational-actor paradigm—especially the version that assumes a desire to maximize expected subjective utility—has serious shortcomings.30 The problems include these: (1) The adversary may not have objectives, values, and a way to evaluate options; (2) Even if he does, they may not be inferable with available information; (3) In many circumstances, stable “utility functions” do not exist: leaders may not know their “true” objectives and values and, in any case, those may change as matters evolve.

The first point has been made by Patrick Morgan, who notes that policy makers often defer deciding on their objectives and value trade-offs, expecting to learn from events and interactions and not wanting to tip their hands early (Morgan, 2003). It is of interest to note how little eventual U.S. war objectives in Iraq and Afghanistan relate to those stated at the outset. More generally, policy research has long demonstrated that many of the most important policy challenges involve “wicked problems” that have no clear solutions. Instead, people work the problems until, as the result of interactions, events, and sometimes weariness, they discover acceptable solutions that reflect history, personalities, and process.31 That is, solutions emerge.

The second item is well illustrated by the case of Saddam Hussein. Only in retrospect is it clear that he had put on hold his nuclear program but kept that

________________

27 See Berrebi (2009) for empirical analysis of terrorist behavior.

28 Henry Kissinger observed, looking back on Egypt’s invasion of Israel in 1973, that “our definition of rationality did not take seriously the notion of Egypt and Syria starting an unwinnable war to restore self-respect” (Kissinger, 2011).

29 The most important work of this type was initiated by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita in the 1980s (Bueno de Mesquita, 1981). Related work continues (see, e.g., National Research Council, 2011, and Abdollahian et al., 2006, with the Senturion model). Similar work at RAND has been led by Eric Larson. Such work, however, is typically not about deterrence per se.

30 The literature on the subject is lengthy: for example, Jervis (1976), Jervis et al. (1985), Green and Shapiro (1994), Lebow and Stein (1989 and other articles in the same issue of World Politics), Morgan (2003), Kahneman (2011), and Davis (2014b).

31 See Rosenhead and Mingers (2002). Wicked problems are more heavily studied in Europe than in the United States, but the approaches resonate with many scholars of policy analysis.

fact secret from nearly everyone in order to influence the United States, Iran, and potential domestic rivals.32 The instability of utility functions is a a fundamental but often-undiscussed problem (Davis, 2014b). Everyone does things that, in retrospect, were not in their best interests even though they seemed right at the time. Leaders are no different, and there is ample laboratory evidence of related matters, including the celebrated paradoxes of behavior described below. 33

The failure of U.S. planning that led to the Bay of Pigs fiasco has long been described as a peacetime example of group-think.34 The widely accepted notion that heavy-handed threats of military attack will deter states such as Iran from developing nuclear weapons, or even having virtual weapon-system capability, may be a modern example (however sensible the goal of persuading Iran to do otherwise). The conditions under which threats do or do not work are not always well understood and can change.

It is perhaps surprising that the literature on deterrence theory continues to be dominated by rational-actor theory, but this is changing with the more widespread appreciation of lessons from psychology accumulated over the last half century or so. Which types of approaches can help in going beyond rational-actor assumptions? The answers include leadership profiling, qualitative cognitive modeling, human gaming with role-playing, the use of alternative adversary models to hedge against uncertainty, and—in principle—even agent-based simulation. Most important, however, is doing the “hard thinking.” After all, people like Herman Kahn and Thomas Schelling discussed many ways in which behaviors would depart from what is ordinarily thought of as rationality.

________________

32 A mass of information is now available on Saddam Hussein’s thinking in both 1990-1991 and 2003 from extensive interviewing, his own lengthy discussions with an FBI questioner while in custody (Woods and Stout, 2010; Woods et al., 2011; Woods, 2008), and even audio and video tapes that Saddam recorded of private conversations (Woods, 2012, p. 4).

33 These have been summarized by Nobelist Daniel Kahneman (Kahneman, 2011) and in a popular book on behavioral economics (Thaler and Sunstein, 2009). Decades of research now exists on actual decision making and behavior, on the role of heuristics and biases, and the sometimes-helpful/sometimes-hurtful role of intuitive decision making (Gigerenzer and Selten, 2002; Klein, 2001, 1998). Those who support decision making should seek to achieve the advantages of both the heuristics-and-biases and naturalistic approaches, while mitigating their shortcomings (Davis et al., 2005; Kahneman, 2011). It is also important to reject the false dichotomy of rationality and psychology (Mercer, 2005). Interestingly, some practitioners of rational-actor modeling have found ways to incorporate some of the nonrational considerations while preserving analytic virtues of the earlier methods. See, for example, Bueno de Mesquita and McDermott (2004).

34 See Janis (1972).

Analytic conclusions about deterrence are often dominated by the assumptions of a planning scenario even though such scenarios are notoriously unreliable and the odds of error are great. The challenge of planning under uncertainty has bedeviled decision making for millennia. This is especially the case for situations of deep uncertainty in which we do not know the relevant probability distributions (if they exist), understand the underlying phenomena, or know how to formulate the decision rigorously. Considerable technical progress has been possible due to the confluence of theoretical work, computational advances, empirical psychology, and other efforts. Addressing deep uncertainties need not mean paralysis; instead, it means pragmatically recognizing and bounding them, assessing the relative significance of the many such uncertainties, and identifying hedges and adaptations.35

Less work has been published on deep uncertainty in connection with deterrence and assurance, but a review of modern decision science for the Air Force Office of Scientific Research drew on historical lessons about flaws in top-level U.S. national security planning in crisis and implications from decision science.36 A major conclusion was that it has been common for flawed decision making to be driven by best estimates about the adversary and that it should be a matter of doctrine for high-level decision-aiding to seek strategies that hedge against potential misunderstanding about the adversary. The report suggested using alternative cognitive models,37 as one mechanism for doing so, pointing out that the empirical evidence is that causing people to entertain even two alternative constructs of how the adversary may be reasoning opens minds, which in turn makes hedging and preparing for adaptation easier. In contrast, devil’s advocate methods often fail because the other position is too heavily discounted and discussions become personalized. The recommended approach is to make consideration of alternative assumption sets more routine and analytic, even doctrinal, depersonalizing the discussion.

Finding 2-1. Deep Uncertainty. Planning to support deterrence and assurance with both current operations and longer-term programs to organize, equip, and train is characterized by deep uncertainty, described more fully in Chapter 3. Nonetheless, methods exist for dealing with such uncertainties effectively, primarily by hedging and capabilities for adaptation.38

________________

35 See section on exploratory analysis in Chapter 3.

36 These aspects of the study were not published at the time because of sensitivities, but a published product (Davis et al., 2005) includes suggestions for decision support motivated in part by history as well as psychological research (pp. 83-93).

37 See National Research Council (1997) and Davis (2010) and references therein.

38 See Hallegatte et al. (2012).

The need for tailoring deterrence is hardly new.39 What is more important is deciding on the “difficult cases” on which deterrence studies should focus—especially when it is not known what crises will occur in the future, or even the circumstances of tomorrow’s crises. Ideally, test cases for planning emerge from in-depth examination of possibilities followed by identification of those cases that, if planned for, will likely provide the capabilities needed to deal with actual crises when they arise. Table 2-4 provides key questions suggesting test cases for analysis. The questions are grouped by the committee in the categories of Peer, Near-Peer, Regional (both Responsible and Rogue), and Nonstate Actors (see Table 2-4).40

Reexamining Ballistic Missile Defense with Extended Deterrence in Mind

One theme that emerges from discussion of modern-day deterrence and assurance is the increasing significance of ballistic missile defenses (BMD). This is indicated by the intense and dedicated efforts of Japan and the increasing interest of other states in these systems.41

Those recalling the Cold War often are skeptical about BMD, seeing offense as more cost-effective than defense and ineffective only against moderately sophisticated countermeasures. However, effective defenses against lower-level threats currently exist, and many of these could be substantially upgraded. Further, the technological balance between offense and defense changes over time. Open minds are important. Still, serious doubts exist regarding the technical viability of effective BMD against large, advanced attacks or even against small attacks by “advanced rogues.” These issues are at the center of the credibility of U.S. extended conventional deterrence to critical allies such as Japan and South Korea.42 DoD includes BMD prominently in its comprehensive approach to regional security discussions with Middle Eastern and Asian-Pacific nations (the initiatives also deal with cy-

________________

39 The strategist Fred C. Iklé sometimes observed wryly that one of the big lessons was that it was necessary to remember that there is no Red and Blue, but instead specific actors such as the United States and Soviet Union (Iklé, 2005).

40 Similar questions are expressed by Keith Payne (2008), who draws on disquieting historical events when expressing skepticism about dependence on deterrence. See, for example, 334 ff.

41 See a Japanese-U.S. study (Research Group on the Japan–U.S. Alliance, 2009).

42 One recent study (National Research Council, 2012) strongly criticizes current DoD programs. Other studies have been more optimistic about the theoretical viability of boost-phase defenses against North Korea and more pessimistic about prospects for effective mid-course discrimination (American Physical Society, 2003; Sessler et al., 2000). Still others are quite critical of current programs for many reasons, including inadequate testing (Coyle, 2013).

TABLE 2-4 Key Questions Suggesting Test Cases for Analysis of Deterrence

|

|

|

| Type of Adversary | Stressful Question |

|

|

|

| Peer | Could Russia find itself providing nuclear deterrence enhancement to regional players such as China or the DPRK, which could transform regional escalatory calculations into global deterrence dynamics? |

|

Near-Peer |

Might China, in a crisis involving Taiwan, see the issues as raising core values (what might even be seen as “sacred values”) about the very nature of China and her place in the world, rather than as disputes about a small island nation with different attitudes but good economic relations with the Mainland?a |

|

Would Chinese military figures interpret events in terms of the United States attempting to squelch China’s natural and proper aspirations as a great power, in which case the stakes would loom larger than might seem “reasonable?” |

|

|

Regional |

Might a future authoritarian leader of a rogue state, analogous to a Saddam Hussein, prefer going down with destruction of his enemies to accepting an island retirement or public hanging?b Would he see events apocalyptically rather than pragmatically? |

|

Might a future leadership of a state such as North Korea see its only possible route to success being to deter the United States, and the only route to success in that being willing to use nuclear weapons on a limited basis against our regional allies, our forces deployed forward such as aircraft carriers, or even the U.S. homeland such as submarine or bomber bases? |

|

|

Might the United States be self-deterred from decisive intervention in protection of an ally because of the credible threat of nuclear attack? What would the nuclear deterrence implications be for the United States of the breakout of nuclear use between India and Pakistan, especially if China were to support Pakistan, etc.? |

|

| Nonstate | How might extremist nonstate actors such as an al-Qaeda use or brandish weapons of mass destruction? What role can deterrence and assurance play in such cases? |

|

|

|

a Sacred values have been addressed with deep social science research (Atran and Axelrod, 2008; Atran, 2010). Such values often lead to behaviors that appear to others as irrational; they are “ignored only with peril when discussing deterrence. Significantly, such matters interact with politics, as when Slobodan Milošević recreated ancient ethnic tensions in firing nationalistic emotions. Another example is how China’s Communist Party has “created” sacred values with respect to Taiwan’s relationship to China.

b Such possibilities were discussed at the end of the Cold War (Watman et al., 1995; Wilkening and Watman, 1995).

bersecurity, space resilience, and other matters).43 It is important to resolve the technical questions to inform both investment and policy.

Observation 2-2. Missile Defense. Because regional and intercontinental missile defenses have become so important to extended deterrence and assurance, a new

________________

43 The comprehensiveness of the approach can be seen in some recent Department of Defense reports (2014; 2010a, pp. 31-35; 2010b).

round of intensive research and debate is needed—with the best science and independent assessment available—to assess what is truly feasible.

Observation 2-3. Extended Deterrence. As during the Cold War, there are inherent credibility problems when the United States seeks to extend deterrence to allies by using nuclear threats against nations that also possess nuclear weapons and could strike the United States. Reassurance efforts, however zealously attempted, may not be persuasive to allies for understandable reasons.

This observation may surprise some readers, but longstanding U.S. allies are having public discussions that include advocates of exploring nuclear weapons options.

Observation 2-4. Dissuasion by Denial. Dissuasion by denial is especially important for the era lying ahead. Relying entirely on the threat of punishment, especially nuclear threat, is fraught with risks—more so than in the past.

What methods might be useful in addressing such matters? In-depth scientific and engineering-level analysis is needed, along with gaming and game-structured modeling, among others. Chapter 3 discusses a number of these.

Anticipating the Unexpected: Technological and Other Drivers of Change

The pace of technological change increases the likelihood of technological surprise with strategic consequences.44 The synergistic advances in information technology (IT), computation, materials, advanced manufacturing, exotic sensors, enhanced energetic materials and fuels, and the like may have direct effects in the areas of air and missile defenses, advanced conventional munitions, ballistic and cruise missiles, antisubmarine warfare, cyberwarfare, counter-space capabilities, and others which could undermine traditional nuclear deterrent forces. These are familiar and enduring challenges for U.S. planners and need no elaboration.

A rather different great challenge is that technologies such as ubiquitous sensors, the Internet, and smartphones are opening the world with the prospect of great situational awareness and communication. At the same time, cyberattack, electromagnetic pulse, and critical infrastructure vulnerabilities raise the prospect of suddenly losing awareness and connectivity. Rapid changes from one state to another are possible, creating a new kind of potential instability.

________________

44 For more background, see Lehman (2013), from which some of the committee’s discussion draws, Bracken (2012), and Defense Science Board (2009, 2010).

In contemplating strategy to avoid or mitigate strategic surprise, past lessons should be recalled. These include (1) nations and nonstate actors do not always follow the paths taken by the United States; (2) silver bullet technologies are rare, but accretion of lesser capabilities can have similar effects; (3) the variety of technologies available, many close to military application, increases the chance of surprise; (4) many military technologies have different values for different players or scenarios; and (5) in a complex world, precise predictions of events and timing is difficult, and, even when predictions are correct, responses are seldom timely and often ineffective (Lehman, 2013).

What can be done? A principle is that strategy should at once seek vigorously to effectively anticipate possible major developments and lay the groundwork for mitigating consequences and exploiting opportunities. History shows that surprise often has badly adverse effects not because events were unforeseeable, but because nothing was done even when warnings were observed or because the ability to adapt to surprises proved poor, or both. Which methods might help? Modern simulations, exploratory analysis, and studies can help by generating a richer understanding of possibilities and consequences, and perhaps by helping to find ways to prepare or hedge. So also, certain types of human gaming can be very helpful, as illustrated by the years of experience with such games by DoD’s Office of Net Assessment, “Foresight exercises” used in planning social policy and various scenario-based methods used in both national security work and private enterprise. These and others are discussed in Chapter 3.

Maintaining the Reality and Perception of Safe, Secure, and Effective Nuclear Forces

Perceptions and Assurance

Deterrence and assurance depend on both the reality and perception, by ourselves and others, of the safety, security, and effectiveness of nuclear forces. Perceptions vary on what nuclear weapons and their delivery systems and infrastructures can do, what they are for, and how others perceive them (a core element of assurance). For example, some allies feel more assured by local deployments while others feel less secure. Some allies have wanted systems that they see tangibly as “their nuclear umbrella,” such as the TLAM-N sea-launched cruise missile, while others have been satisfied seeing central system components such as sea-launched ballistic missiles. Even the nature of individual nuclear warheads can be controversial. The value of reducing the yields of warheads is emphasized by some as a sign of restraint or an act to increase their credibility as a deterrent.

Potential adversaries may also have different perceptions of the significance of force characteristics. The Soviet Union placed a greater emphasis on geographical location of forces than did the United States, with NATO’s forward-deployed forces seen as strategic because they could hit the Soviet homeland. While the United States emphasized the robustness, flexibility, survivability, and agility of a strategic triad, the Soviet Union relied heavily on the coercive power of its highly multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV)ed, liquid-fueled heavy missiles. The United States has eliminated battlefield nuclear weapons and keeps only a small force of air-delivered tactical weapons. In contrast, Russia has shown renewed interest in modern, low-yield tactical and battlefield weapons. Other measures on which perceptions vary include fast versus slow flyers, alert rates, unit versus force survivability, day-to-day versus generated force postures, individual versus force performance, dependence on warning, and safety and security measures. This study did not examine such issues in detail but thought that they should be highlighted in future Air Force and DoD efforts to address safety, security, and effectiveness.

Efforts to assure that forces are safe, secure, and effectiveness should recognize and deal explicitly with alternative perspectives on how to measure them, thereby anticipating and dealing with perceptions crucial to both deterrence and assurance.

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) within the Department of Energy has the responsibility for maintaining a safe, secure, and effective nuclear weapons stockpile without underground nuclear testing. It provides an annual report to the Congress (Department of Energy, 2013). The current weapons stockpile and the design technology within it are old. According to the NNSA website,

Most nuclear weapons in the U.S. stockpile were produced anywhere from 30 to 40 years ago, and no new nuclear weapons have been produced since the end of the Cold War. At the time of their original production, the nuclear weapons were not designed or intended to last indefinitely.45

The absolute and relative ability of different nations to sustain existing nuclear weapons, or perhaps to design and deploy reliable “new” nuclear weapons without testing, is subject to debate. Although what is meant by “new” or “modernized” nuclear weapons involves a range of definitions and considerable debate, many scientists believe that it is possible to develop and deploy some “new” or “modernized” nuclear weapons without full-scale testing. Indeed, China, Pakistan, and Russia have taken that course.

________________

45 For additional information, see NNSA, “Maintain the Stockpile,” http://nnsa.energy.gov/ourmission/managingthestockpile, accessed January 29, 2014.

Prohibiting actual weapon-detonation tests has, under the Strategic Stockpile Management Plan, forced U.S. reliance on subcomponent and noncritical nuclear tests, analysis, and scientific modeling and simulation. The program includes life extension efforts, updating subsystem technology and components to improve reliability and safety, and replacing end-of-life components. An alternative approach, the Reliable Replacement Warhead program, a program to develop a family of “new” warheads embodying advanced technologies and designs intended to be highly reliable and more sustainable (Congressional Research Service, 2005) was terminated in 2009. Consequently, the Life-Extension Program (LEP) remains the main mechanism for achieving sustainability. This program is expensive, which is why the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Program 2014 (Department of Energy, 2013) calls for a reduction in the types of nuclear warhead designs in the inventory that need to be sustained. This plan calls for reducing the B61 series to just the new B61-12, which will consolidate the B61-3, -4,-7, and -10, completing the W76-1 LEP earlier, and a W88 Alteration program. The long-term plan is the so-called “3+2 vision,” which calls for shrinking the stockpile to just three ballistic missile warheads and two air-delivered warheads. Although this would limit flexibility for future systems and increase some risks associated with common-mode failures (while perhaps reducing others), it would greatly reduce the cost of maintenance, safety, and support of the inventory, while retaining a strategic-upload hedge in the ballistic missile force at lower numbers and cost. Whether this strategy can be sustained with adequate funding over the long term remains to be seen.

Are these judgments valid today? Are things better or worse? The committee did no independent research on these matters, but committee members were concerned about patterns of decision and behavior on weapons (described in briefings to the committee) that are at odds with what would ordinarily be expected for critical systems that are supposed to be safe, secure, and effective. Proponents of the current approach point to past testimony and reports from officials, general officers, and scientists, which would seem to provide confidence in such matters. However, in the committee’s reading they underplay troubling judgments. Five years ago, a congressional commission chaired by William Perry and James Schlesinger (United States Institute of Peace, 2009, pp. 40-41) reported as follows:

The possibility of using this approach [current policy] to extend the life of the current arsenal of weapons indefinitely is limited. It might have been possible to do so had the United States designed differently the weapons it produced in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. But it chose to optimize the design of the weapons for various purposes, for example, to maximize the yield of the weapon relative to its size and weight. It did not design them for remanufacture. This approach also requires that the United States utilize or replicate some materials or technologies that are no longer available. Designs constraints also prevent the utilization of advanced safety and security technologies…. The process of remanufacturing now underway introduces some uncertainty about the expected operational reliability

of the weapons. So far at least, the directors of the weapons laboratories have been able to certify that they retain confidence in the remanufactured (and other stockpiled) weapons. But there are increasing concerns about how long such confidence will remain as the process of reinspecting and remanufacturing these weapons continues. Indeed, laboratory directors have testified that uncertainties are increasing.

Again, the committee did not have the time or budget for independent research on these matters, which relate strongly to the subject of its report and are important to the Air Force. It seems likely that at some point—despite the sensitivity related to these topics and the likely disruptive effects—the nation will review all of these matters and either reaffirm or alter stockpile-related policies and programs. If a clean-sheet-of-paper approach is taken, the committee believes that, while new analytic methods will be useful and internal peer review should be strengthened, it would also be valuable to give a major role to scientific and technical experts from outside of the current nuclear enterprise. Such experts would have fresh eyes and would have more independent perspectives with respect to the feasibility, wisdom, and affordability of continuing to repair and replace components developed decades ago.

Another crucial subject that the committee was unable to look into during its short study was nuclear command and control. Logically, this deserves to be covered in a study of nuclear deterrence and assurance. Further, it is an important and troubled subject area. DoD initiatives in the last several years, championed by Ashton Carter while he was Deputy Secretary of Defense, sought vigorously to remedy problems of technological obsolescence and various other problems at the nuclear-enterprise level. Little public information is available as yet about what progress has been made and what remains to be done. This report can only highlight the problem area as one worthy of top-level attention, especially by the Air Force, the Navy, and DoD. The relevant analytic methods already exist, so the subject is not addressed in Chapter 3 or the remainder of the report. Nor are issues related to management of the nuclear enterprise, as discussed in a report chaired by James Schlesinger in the wake of weapon-mishandling incidents that led to the dismissal by Secretary Gates of the Secretary and Chief of Staff of the Air Force.46

Given the breadth of challenges involving the nuclear enterprise and particularly the Air Force role within it, there is need not only for improved policies and management, which has been discussed elsewhere (as in the references cited above and DoD directives), but also on the analytic front.

________________

46 See Schlesinger et al. (2008a,b) and a follow-up by the Defense Science Board on response by the Air Force (Defense Science Board, 2013a).

Finding 2-2. Analytic Framework. Because the U.S. approach to strategic deterrence and assurance needs to be continually adapted, a management plan is required that defines comprehensively the set of continuing analytic foci, which includes nuclear command and control; air and missile defense; cyber, space, geostrategic, and technological changes; and the challenges of tailoring deterrence and assurance to adversaries and allies. This analytic management plan is in addition to tasks related to weapons, forces, personnel, and the nuclear enterprise in general.

This chapter has sought to lay out the issues and challenges. Chapter 3 discusses methods and tools that seem valuable for future study of, planning for, and operations of nuclear forces. It prefaces that discussion with strong words emphasizing that the expertise and sophistication of analysts is more important than improvement in methods.

Abdollahian, M., M. Barnick, B. Efird, and J. Kugler. 2006. Senturion: A Predictive Political Simulation Model. National Defense University Center for Technology Security Policy, Washington, D.C.

Adamsky, D. Forthcoming. “Deterrence by Denial in Israeli Strategic Thinking” in Deterrence by Denial: Theory, Practice and Empiricism (A. Wenger and A. Wilner, eds.)

Albeck, K., and S. Handelman. 1999. Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World—Told From Inside by the Man Who Ran It. Random House, New York.

American Physical Society. 2003. Report of the American Physical Society Study Group on Boost-Phase Intercept Systems for National Missile Defense. College Park, Md.

Arbvatov, A., and V. Dvorkin. 2013. The Great Strategic Triangle. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Washington, D.C. http://carnegieendowment.org/files/strategic_triangle.pdf.

Atran, S. 2010. Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un) Making of Terrorists. Eco Press, New York.

Atran, S., and R. Axelrod. 2008. In theory: Reframing sacred values. Negotiation Journal (July):221-245.

Bennett, B. 2013. The Challenge of North Korean Biological Weapons. RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif. http://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CT401.html.

Berrebi, C. 2009. “Economics of terrorism and counterterrorism: What matters and is rational-choice theory helpful?” Pp. 151-208 in Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together (P. Davis and K. Cragin, eds.). RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Bracken, P. 2012. The Second Nuclear Age: Strategy, Danger, and the New Power Politics. Henry Holt and Company, New York.

Brown, H. 1981. Annual Report FY 1982. Department of Defense, Washington, D.C.

Brown, H. 1983. Thinking About National Security: Defense and Foreign Policy in a Dangerous World. Westview Press, Boulder, Colo.

Bueno de Mesquita, B. 1981. The War Trap. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., and R. McDermott. 2004. Crossing no man’s land: Cooperation from the trenches. Political Psychology 25(2):271-287.

Burr, W. 2005. “The Nixon Administration, the SIOP, and the Search for Limited Nuclear Options, 1969-1974.” In National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 173. http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB173/.

Clarke, R., and A. Steve. 2013. Cyberwar’s Threat Does Not Justify a New Policy of Nuclear Deterrence. Washington Post. June 14. http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/cyberwars-threat-does-not-justify-a-new-policyof-nuclear-deterrence/2013/06/14/91c01bb6-d50e-11e2-a73e-826d299ff459_story.html.

Coe, A., and V. Utgoff. 2008. Understanding Conflicts in a More Proliferated World. Institute for Defense Analyses, Alexandria, Va.

Colby, E. 2013. Cyberwar and the nuclear option. National Interest. June 24. http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/cyberwar-the-nuclear-option-8638.

Colby, E.A., and M.S. Gerson, eds. 2013. Strategic Stability: Contending Interpretations. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press, Carlisle, Pa. http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=1144.

Colby, E.A., and E. Ratner. 2014. Roiling the waters. Foreign Policy. January 21. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2014/01/21/roiling_the_waters.

Congressional Research Service. 2005. Nuclear Weapons: The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program. Washington, D.C.

Coyle, P.E. 2013. Back to the drawing board: The need for sound science in U.S. missile defense. Arms Control Today. January/February. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2013_01-02/Back-to-the-Drawing-Board-TheNeed-for-Sound-Science-in-US-Missile-Defense.

Crawford, T.W. 2003. Pivotal Deterrence: Third-Party Statecraft and the Pursuit of Peace. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Danzig, R.J. 2009. A Policymaker’s Guide to Bioterrorism and What to Do About It. Center for Technology and National Security Policy, National Defense University, Washington, D.C.

Davis, P.K. 2010. Simple Models to Explore Deterrence and More General Influence in the War with Al-Qaeda. RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Davis, P.K. 2011. “Structuring Analysis to Support Future Nuclear Forces and Postures.” RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Davis, P.K. 2014a. “Deterrence, Influence, Cyber Attack, and Cyberwar.” WR-1049. RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif. http://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR1049.html.

Davis, P.K. 2014b. “Toward Theory for Dissuasion (or Deterrence) by Denial.” WR-1027. RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif. http://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR1027.html.

Davis, P.K., and B.M. Jenkins. 2002. “Deterrence and Influence in Counterterrorism: A Component in the War on Al Qaeda.” RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Davis, P.K., and P.A. Wilson. 2011. “Looming Discontinuities in U.S. Military Strategy and Defense Planning,” RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Davis, P.K., J. Kulick, and M. Egner. 2005. “Implications of Modern Decision Science for Military Decision Support Systems.” RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Defense Science Board. 2009. Capability Surprise Volume I: Main Report. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, Washington, D.C.

____. 2010. Capability Surprise Volume II: Supporting Papers. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, Washington, D.C.

____. 2013a. Air Force Nuclear Enterprise Follow-on Review. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, Washington, D.C.

____. 2013b. Resilient Military Systems and the Advanced Cyber Threat. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, Washington, D.C.

Delpech, T. 2012. “Nuclear Deterrence in the 21st Century: Lessons from the Cold War for a New Era of Strategic Piracy.” RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Department of Defense. 2010a. Ballstic Missile Defense Review Report. Washington, D.C.

____. 2010b. Nuclear Posture Review Report. Washington, D.C.

____. 2010c. Report of the Quadrennial Defense Review, Washington, D.C. http://www.defense.gov/qdr/qdr%20as%20of%2029jan10%201600.pdf.

____. 2014. Report of the Quadrennial Defense Review. Washington, D.C. http://www.defense.gov/pubs/2014_Quadrennial_Defense_Review.pdf.

Department of Energy. 2013. Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan. Washington, D.C. http://nnsa.energy.gov/sites/default/files/nnsa/06-13-inlinefiles/FY14SSMP_2.pdf.

Dobbs, M. 2008. One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Doron, A. 2004. Cumulative deterrence and the war on terrorism. Parameters (Winter):4-19.

Fursenko, A.A., and T.J. Naftali. 1997. One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964. Norton, New York.

Garthoff, R.L. 1992. The Havana conference on the Cuban missile crisis in Cold War international history. Project Bulletin No. 1. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C.

George, A.L. 2003. The need for influence theory and actor-specific behavioral models of adversaries. Pp. 271-310 in Know Thy Enemy: Profiles of Adversary Leaders and Their Strategic Cultures, 2nd. ed. (B.R. Schneider and J.M. Post, eds.). USAF Counterproliferation Center, Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., and Washington, D.C.

George, A.L., and R. Smoke. 1974. Deterrence In American Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice. Columbia University Press, New York.

Gigerenzer, G., and R. Selten. 2002. Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Green, D.P., and I. Shapiro. 1994. Pathologies of Rational Choice Theory: A Critique of Applications in Political Science. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Hallegatte, S., A. Shah, R. Lempert, C. Brown, and S. Gill. 2012. “Investment Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty: Application to Climate Change.” World Bank Policy Research Paper 6193. http://econ.worldbank.org.

Iklé, F.C. 2005. Every War Must End. Columbia University Press, New York.

Janis, I. 1972. Victims of Groupthink; A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Mass.

Jervis, R. 1976. Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Jervis, R., R.N. Lebow, and J.G. Stein. 1985. Psychology and Deterrence. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Md.

Kahn, H. 1960. On Thermonuclear War. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Khan, K. 2005. Limited War Under the Nuclear Umbrella and Its Implications for South Asia. Stimson Center, Washington, D.C.

Khan, F.H. 2012. Eating Grass: the Making of the Pakistani Bomb. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif.

Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

Kissinger, H. 2011. Henry, Years of Upheaval. Simon and Schuster, New York.

Klein, G. 1998. Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Klein, G. 2001.The fiction of optimization. Pp. 103-121 in Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Tookit (G. Gigerenzer and R. Selten, eds.) MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Kokoshin, A. 2012. “Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis in the Context of Strategic Stability.” Discussion Paper 12. Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center, Cambridge, Mass.

Lebow, R.N., and J.G. Stein. 1989. Rational Deterrence Theory: I think, therefore I deter. World Politics 41(2): 208-224.

Lederberg, J., ed. 1999. Biological Weapons: Limiting the Threat. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Lehman, R.F. 2013. Future technology and strategic stability. Pp. 147-200 in Strategic Stability: Contending Interpretations (E.A. Colby and M.S. Gerson, eds.). U.S. Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, Pa.

Leitenberg, M., R. Zilinskas, and J.H. Kyhn. 2012. The Soviet Biological Weapons Program: A History. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Long, A. 2008. Deterrence: From Cold War to Long War. RAND Corp., Santa Monica, Calif.

Lowther, A., ed. 2013. Thinking about Deterrence: Enduring Questions in a Time of Rising Powers, Rogue Regimes, and Terrorism. Air University Press, Air Force Research Institute, Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala.

Mastny, V., S.G. Holtsmark, and A. Wenger, eds. 2013. War Plans and Alliances in the Cold War: Threat Perceptions in the East and West. Routledge, London, England.

Mercer, J. 2005. Prospect theory and political science. Annual Reviews of Political Science 8:1-21.

Morgan, P.M. 1983. Deterrence: A Conceptual Analysis, 2nd. ed. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, Calif.

Morgan, P.M. 2003. Deterrence Now. Cambridge University Press, London.

Nathan, J.A., ed. 1992. The Cuban Missile Crisis Revisited. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

National Archives Project. Undated. Interview with Robert McNamara. Episode 11 Vietnam. George Washington University. http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/coldwar/interviews/episode-11/mcnamara4.html. Accessed February 11, 2014.

National Research Council. 1997. Post Cold War Conflict Deterrence. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

____. 2011. Intelligence Analysis: Behavioral and Social Scientific Foundations. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

____. 2012. Making Sense of Ballistic Missile Defense: An Assessment of Concepts and Systems for U.S. Boost-Phase Missile Defense in Comparison to Other Alternatives. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

Payne, K.B. 2008. The Great American Gamble: Deterrence Theory and Practice From the Cold War to the Twenty-First Century. National Institute Press, Fairfax, Va.

Quinlan, M. 2009. Thinking about Nuclear Weapons Principles, Problems, Prospects. Oxford University Press. Oxford, U.K.

Research Group on the Japan-US Alliance. 2009. A New Phase in the Japan-US Alliance. Institute for International Policy Studies.

Rid, T. 2012. Deterrence beyond the state: The Israeli experience. Comparative Strategic Policy 33(1):122-147.

Rosenhead, J., and J. Mingers. 2002. A new paradigm of analysis. Pp 1-19 in Rational Analysis or a Problematic World Revisited: Problem Structuring Methods for Complexity, Uncertainty and Conflict (J. Rosenhead and J. Mingers, eds.). John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, U.K.

Sanger, D.E. 2012. Confront and Conceal: Obama’s Secret Wars and Surprising Use of American Power. Crown Publishing, New York.