Selected Discussion of Tools, Methods, and Approaches for Deterrence and Assurance

The committee reviewed analytic tools, methods, and approaches (collectively referred to henceforth as “methods”) to address deterrence and assurance problems. It drew on members’ prior expertise and previous reviews and held as information-gathering meetings. This chapter summarizes by identifying—with caveats—methods that have significant potential. Some general observations include the following:

1. None of the methods are “commodities” to be purchased to find “answers.” Rather, they are merely aids to research, analysis, and decision making.

2. The value of analysis depends primarily on the talent, education, and experience of the analysts and their work environments.

3. Analysis quality is greatly improved if the people involved have been exposed to an interdisciplinary range of methods in the course of their careers through classroom learning, experiential learning (e.g., gaming), analysis, and practical experience.

4. Analytic organizations need method suites—a plentiful kit bag. For a particular purpose, the analyst may use intellectual capital, draw from the kit bag, or reach out to experts in applying the methods well.

5. Significant improvements in deterrence and assurance analysis are possible with synthesis using hybrid methods. The analysis community has tribes that do

not routinely interact, but much can be gained by forcing interactions (e.g., among gamers, modelers, empiricists, and analysts).

6. In looking back to 20th-century developments in deterrence and assurance theory, the biggest payoffs were insights, frameworks, and strategies rather than the nuts and bolts of methods. The primary benefit of game theory, for example, was facility not in solving academic game-theory math problems but in conveying concepts such as how to recognize prisoner-dilemma-type tensions, opportunities for a non-zero-sum game approach, and the pressures creating Chicken-game behavior.

Observation 3-1. Building Air Force Subject Matter Expertise. Improving analysis of deterrence and assurance problems will depend on the systematic education and nurturing of experts that exposes them over time to a rich suite of methods.

Finding 3-1. Long-Term Career Development. Education and nurturing of experts in deterrence and assurance will not happen without a management plan to do so in the Air Force (and other services, particularly the Navy), partly in coordination with joint assignments but also bearing in mind longer-term career development and assuring adequate expertise (a Service responsibility).

After considering a much broader range of methods, the committee pruned to the still-sizable list in Table 3-1. The leftmost column groups the methods in three major classes: those that help to collect, organize, or analyze data; those that involve knowledge structuring, model building, and theory building; and those for analysis to aid decision making. The committee did not include methods regarded as simply part of the baseline (e.g., operations research, statistics, quantitative political science, simulation, standard game theory, and standard decision analysis) or as having less potential for deterrence and assurance. Subsequent columns in Table 3-1 connect to the issues identified in Chapter 2 as particularly important for the study. The committee identified some methods relevant to all of those issues. The number of bullets shown in the table cells convey a rough sense of relative strength with no pretense of rigor.

The following sections cover the individual methods in the left column in the order shown (readers may wish to proceed in a different order). Level of discussion varies based on the methods’ relative familiarity, their significance to the study, and the committee’s use of appendixes for detail. The issue of validation is discussed along the way.

TABLE 3-1 Selected Methods to Address Issues in Analysis of Deterrence and Assurance

| Methods | General Deterrence | Test Cases for Planning | Beyond Rational Actor | Planning Under Uncertainty | Anticipating the Unexpected | Safe, Secure, and Effective |

| Empirical and quasiempirical | ||||||

|

Data collection |

•• | •• | •• | •• | •• | |

|

Crowdsourcing |

||||||

|

Data mining |

||||||

|

Social science analytics |

•••• | •• | •••• | •• | •• | |

|

Case studies and narratives |

||||||

|

Content analysis and profiling |

||||||

|

Social network analysis |

||||||

|

Gaming and computational experimentation |

•••• | •• | •••• | •• | •• | |

|

Human gaming |

||||||

|

Computational experimentation |

||||||

| Knowledge organization, modeling, and theory | ||||||

|

Frameworks and qualitative modeling |

•••• | •••• | •••• | •••• | •• | •• |

|

Broadened framework of decision making |

||||||

|

Complex adaptive systems |

||||||

|

Causal system depictions |

||||||

|

Qualitative system modeling |

||||||

|

System diagrams |

||||||

|

Factor trees, cognitive maps and models |

||||||

|

Qualitative game theory |

||||||

|

Computational modeling |

•• | •• | •• | |||

|

System dynamics, Bayesian nets, influence nets |

||||||

|

Game-structured agent-based modeling |

||||||

|

Modeling of limited rationality |

||||||

| Analysis | ||||||

|

Analysis methods |

•••• | •••• | •••• | •••• | •••• | •••• |

|

Leadership profiling |

||||||

|

Analyzing receptivity issues |

||||||

|

Exploratory analysis and robust decision making |

||||||

|

Strategic portfolio analysis |

||||||

| Synergy across methods | •••• | •••• | •••• | •••• | •••• | |

NOTE: Number of bullets indicates subjectively assessed relative applicability.

EMPIRICAL: DATA COLLECTION AND SOCIAL SCIENCE ANALYSIS

The committee begins with empirical methods for crowdsourcing and mining of big data.

Crowdsourcing taps into the knowledge of a group of people with diverse perspectives, sources of information, or ideas about an issue of interest. It reflects the Aristotelian view that wisdom is to be found in the mean: that querying numerous individuals with knowledge of different aspects of a problem will produce the most comprehensive and truthful picture. Crowdsourcing is most commonly associated with extraction of knowledge from geographically distributed groups, especially via the Internet. It has a different purpose and character than usual public polling.

One approach to crowdsourcing uses a wiki-type collaboration information system that allows knowledgeable people to modify information until the crowd reaches relative consensus. Another approach has “information markets” in which invited or self-selected participants bet on the likelihoods of future events or responses to those events. This approach can yield on-the-ground information from, for example, locals, aid workers, journalists, and others. Web-based methods, especially where immediacy and absolute precision are unnecessary, can be significantly less costly than other collection methods

Caveats. The cautions in interpreting crowd-sourced results are similar to those for interpreting public opinion polling. What types of individuals contributed? Did they have good information? What were their likely biases and how representative were they for the information asked? Second, variation is important. Were there significant outliers or a bimodal distribution, in which case the aggregation could be misleading? A problem related to the first caution is that it can be difficult to identify, check, and incentivize the most appropriate individuals to contribute. In particular, government-run crowdsourcing may be viewed with suspicion. For this or other reasons, private companies can sometimes do better in this regard.1

Experiments, observations, and numerical simulations in science and business are currently generating terabytes of data, verging on petabytes and beyond.2 In contrast to traditional isolated analysis, the paradigm for “big data” is often for

________________

1 Companies offering crowd sourcing analyses include Monitor 360 and Wikistrat. RAND researchers have also developed a system Called ExpertLens (Dalal et al., 2011).

2 Terabyte, petabyte, and exabyte correspond to 1012, 1015, and 1018 bytes, respectively.

highly distributed groups to share data routinely.3 Analyzing such information has led to breakthroughs in such fields as genomics, astronomy and high energy physics. The scientific community and the defense enterprise have long generated and used large data sets, but the commercial sector is now a major player. Google, Yahoo!, and Microsoft have data in exabytes. Some social media (e.g., Facebook, YouTube, Twitter) have hundreds of millions of users.

Data mining is transforming the way one thinks about “crisis response, marketing, entertainment, cybersecurity, and national intelligence” (National Research Council, 2013). It is also transforming how one thinks about information storage and retrieval. “Collections of documents, images, videos, and networks are thought of not merely as bit strings to be stored, indexed, and retrieved but also as potential sources of discovery and knowledge”—although exploiting the potential requires “sophisticated analysis techniques that go far beyond classical indexing and keyword counting”—such as finding relational and semantic interpretations of the underlying phenomena (National Research Council, 2013).

Caveats. The potential of the big data approach is undeniable. At the time of its study, however, the committee did not yet see successful unclassified applications clearly relevant to deterrence and assurance, although it noted opportunities as mentioned in the later section on Content Analysis. Further, the committee noted that inquiry seems to be strongly data-driven without adequate grounding in theory and with “validation” often discussed only in statistical terms. The committee did not look into intelligence efforts, such as those of the National Security Agency (NSA), where the situation may be different.

Some of the most important social science methods relevant to deterrence and assurance involve comparative case studies or the somewhat related approach of cultural narratives. Although not new, both are underused in DoD’s work on deterrence and assurance.

Comparative Case Studies

“Structured, focused comparison of cases” (George and Bennet, 2005) can illuminate how deterrence, assurance, dissuasion, and compellence actions and messages have been handled in real-world crises. Scholars working with such diverse sources as memoirs, declassified archives, oral histories, public statements

________________

3 This discussion is based on a National Research Council report (2013).

and documents, and with secondary literature as well, describe with a high degree of fidelity and texture the context for and activities in cases, including cases in which the background of nuclear weapons played a role. It is of particular value to compare studies chosen to be different along important situational dimensions. Doing so converts descriptive explanations of case outcomes into analytic causal but contingent explanations: a form of inductive theory building rather than raw empiricism. It identifies the “real” factors that appear to have been at work (e.g., sometimes personal and emotional, sometimes political) rather than restricting discussion to easily measured abstractions (e.g., population or force ratios).

Caveat. The final history is never written. Case studies must be revisited as new information arises that alters the inferred story, to include perceiving how deterrence was attempted and how signals were perceived.4 Comparisons and debates are important because results can depend on both methodology and assumptions.

Cultural-Narrative Case Studies

A narrative is a spoken or written account of connected events. Cultural narratives are about a society’s ideas, customs, and social behaviors. Understanding them may improve deterrence and assurance by allowing better messages to be crafted for a particular population or leader. Narratives are defined by their sequence and consequences with events selected, organized, connected, and evaluated as meaningful for a particular audience (Riessman, 1993). They shed light on such aspects of culture as values, morals, and perspectives (Chay, 2013). Narratives are seen as produced by people in a specific social, historical, and/or cultural context, and as devices through which individuals represent themselves and the world around them (Griffin, 2013). An example of where narrative analysis may be useful for deterrence and assurance is when it reveals “sacred values,” defense of which may cause behaviors that would appear irrational to those from another culture.

Narrative analysis includes thematic, structural, interactional, and performative aspects. Thematic analysis focuses on the “what”—that is, on the meaning rather than the language used. It looks across stories in different styles to find common elements of meaning. Structural analysis focuses on how a story is told—examining syntax, rhythm, and pattern of words and sounds. It is currently arduous for long narratives. Interactional analysis emphasizes the process of teller and listener—that is, the exchange between storyteller and listener; it usually requires transcripts of conversation. Performative analysis examines the method of transmission, including who is involved, who persuades, and who does the storytelling.

Caveats. Understanding narratives is unquestionably important (as has long been recognized by intelligence services), but even a valid narrative for a society

________________

4 See Gerson (2010) for an example mentioned also in Chapter 2.

may not be characteristic of how leadership will reason or act. To some extent, leaders choose among themes or even modify them (think of Anwar Sadat in 1977 or Vladimir Putin in 2014). It is also possible to detect a valid theme but exaggerate its importance in determining actions. It follows that narrative analysis is probably more valuable for identifying factors and possible reasoning patterns than in reliably predicting actions.

Related Methods

The committee considered a number of other methods that, broadly speaking, are in the same category as case studies and narrative but are not discussed here. In particular, the committee was briefed by William Casebeer of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) on a program concerned with narratives, neurobiology, and implications for subjects such as radicalization and messaging strategies. See particularly Post (2003), including articles by Margaret Hermann and others.

Content Analysis and Profiling

Content analysis is the systematic retrieval of contents from a picture or a text. The content may be fact or fiction and may be manifest or latent (obvious or inferred). It may be keyed to different units such as words, phrases, sentences, or paragraphs. The assumption in content analysis is that the material studied contains information about the source’s state of mind or information. Content analysis draws on data from, among other things, dreams and diaries, feelings and thoughts, and behavior and events in human societies (McClelland, 1961; Carney, 1972; Holsti, 1969). As discussed later in this chapter under “Analysis Methods” and in much more detail in Appendix E, modern quantitative content analysis can be a powerful tool in developing and updating leadership profiles directly useful for deterrence and assurance.

Information retrieval more generally may be qualitative or quantitative and may be recorded in narrative, statistical, or visual formats. Related tools are ordinarily based on theoretical constructs that help interpret the results. Several constructs categorize behaviors in world politics. The basic categories of behavior are (1) types of words and deeds and (2) types of cooperation and conflict behavior. Evidence on the behaviors is retrieved from sources such as newspapers and other media. Trends are then observed regarding the variety, sequence, volume, and intensity of actor behaviors in interactions with others. Speeches and interviews are analyzed to retrieve thoughts, beliefs, emotions, and motivations (Post, 2003). Well-validated tools are available, some of them automated (Smith, 1992; Post, 2003; Young, 2001).

TABLE 3-2 An Example of a Taxonomy and Scale for Interactions

| Conflict | Cooperation | |||

| Deeds | Words | Words | Deeds | |

| Force (−10) | Threaten (−5) | Approve (+1) | Yield (+6) | |

| Seize (−9) | Warn (−4) | Consult (+2) | Grant (+7) | |

| Expel (−8) | Demand/accuse (−3) | Request (+3) | Reward (+8) | |

| Reduce relations (−7) | Protest (−2) | Propose (+4) | Agree (+9) | |

| Demonstrate (−6) | Reject/deny (−1) | Promise (+5) | ||

NOTE: Numbers in parentheses illustrate values of escalation and de-escalation of conflict or cooperation behavior.

SOURCE: Data from McClelland (1972, pp. 96-97; 1968, p. 168).

Prominent examples in world politics use scales developed some years ago (McClelland, 1966; Schrodt, 1994; and Goldstein, 1992). All of these base their categories on word/deed and conflict/ cooperation distinctions. The automated descendants of these early coding schemes employ dictionaries of synonyms for various transitive verbs. They retrieve not only verbs, but also nouns representing the relevant subjects and objects of the verbs in the text. It is now possible to conduct a huge quantitative content analysis of electronic text quickly.

Table 3-2 illustrates a scale stemming from such work. Such a scale might describe evidence relating to escalation, de-escalation, or cooperation over a crisis period. The scale uses event categories from the World Event Interactions Survey (McClelland, 1972; see also McClelland and Hoggard, 1969). They distinguish cooperation and conflict by rankings along a continuum of words and deeds, with deeds ranked as more intense instances of cooperation or conflict than words. The scales used (−10 to 10, with protocols for assigning values) have been subjected to both conceptual and empirical scrutiny for reliability and validity (e.g., McClelland and Hoggard, 1969; Hermann 1971; Kegley, 1973; Beer et al., 1992). The assessments report good reliability except for some problematic distinctions among categories at the upper end of the cooperation continuum (Beer et al., 1992).

Scholarly controversies exist over whether these categories should be seen as measuring intervals, measuring ordinal rankings, or simply indicating nominal but independent categories. Thus, the methods may be seen as quantitative or qualitative (McClelland, 1983; Howell, 1983; Vincent, 1983; Beer et al., 1992), which affects the mathematical sophistication that can be used. However, even the more qualitative versions allow monitoring activities for changes in indicated trends toward escalation, de-escalation, or cooperation, and perhaps what actions may

be expected of an adversary or ally (Walker et al., 2011; Walker, 2013). Again, see Appendix E for more details relevant to deterrence and assurance.

Caveats. Practitioners have varied skill—for example, in extracting valid insights in the midst of boilerplate and sometimes hypocritical prose. Also, certain kinds of evidence can be manipulated (a country may, for example, release materials intended to threaten and scare without the intention of action, or may release materials intended to soothe despite actual malintent).

Sometimes deterrence requires understanding groups and networks rather than just individuals. An element of doing so is social network analysis (SNA). In the popular psyche the notion of tracing complex networks of social connections shows up in the common acceptance of the idea that any two people on Earth are separated by no more than six degrees of separation, as popularized in the Broadway play by John Guare and the popular Kevin Bacon game.5

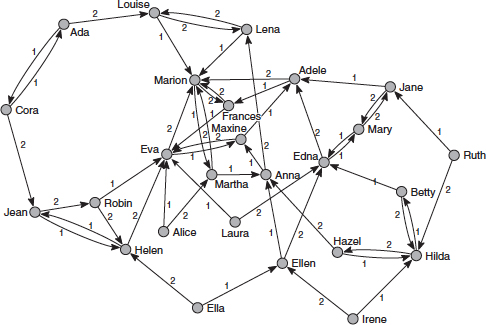

SNA refers to an application of network theory to the study of complex, formal and informal social systems.6 SNA views the links between actors as the “channels for transfer or ‘flow’ of resources (either material or nonmaterial)” (Wasserman and Faust, 1994, p. 4).7 The unit of analysis is not the actor itself but the network that consists of the actors and the linkages between them. SNA can be applied to vastly different networks, such as national-leadership groups, graduates of military academies and exchange programs, academic researchers, or to church and neighborhood groups. Typically analysts begin an SNA analysis by constructing an adjacency matrix or a sociogram to visualize a social structure in which people or organizations are represented as “nodes” and the relationships or linkages as “edges” (see Figure 3-1). Linkages can be direct (e.g., brothers, sisters, coworkers), or indirect, as in a common demographic such as age or sex or some other shared attributes (graduation from the same college).

Once the network has been defined, metrics can be calculated to aid in analysis and interpretation. Centrality measures characterize the relative importance of a node in a network—for example, “degree centrality” which calculates the number of direct ties to a node; “betweenness centrality,” which measures the relative importance of a particular node by how many other nodes it connects to; and

________________

5 To play the Kevin Bacon game, players search for the shortest connections between a chosen individual and the actor. For example, an individual’s Bacon number would be 6 if his or her second cousin was Anne Bancroft, Anne Bancroft was in Waking Ned with Ian Bannen; Ian Bannen was in Braveheart with Mel Gibson; Mel Gibson was in Bird on a Wire with Goldie Hawn; Goldie Hawn was in Housesitter with Steve Martin; and Steve Martin was in Novocain with Kevin Bacon.

6 Sociogram source: de Nooy et al. (2005, p. 5).

7 Wasserman and Faust (1994).

FIGURE 3-1 Nodes and edges in a social network. SOURCE: de Nooy et al. (2005), copyright 2005, reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

“Eigenvector centrality,” which measures a node’s influence by the number of its connections while giving greater weight to high-value connections.

SNA has been widely applied in sociology and other social sciences. It has proved useful in applied settings such as law enforcement, threat finance, counterinsurgency, and counterterrorism. In the area of deterrence- and assurance-related assessment, SNA can be used to test models and hypotheses about relational structures or networks. It would be an appropriate tool for addressing questions of the following types: Which nodes (individuals, organizations, etc.) in a network are the most critical to its operation? What is the structure, density, and size of a human network? What is the nature of the power relations? How has a group gained and retained its power? How can a leader be influenced by threatening to or actually affecting those to whom he is linked and on whom he is dependent for power?

Caveats. The compilation and coding of network information can be long and tedious. Moreover, while relatively simple in concept, analytic interpretation of centrality and other measures requires knowledge and technical expertise. Also, SNA’s scope is limited. It would not be an appropriate method to assess, for example, the substance of an actor’s intention and world view, leadership style, decision-making style under threat or stress, or other nonnetwork-related attributes and behaviors.

QUASIEMPIRICAL SOURCES: GAMING AND COMPUTATIONAL MODELING

This section discusses important sources of what we have called quasi-empirical information in the categories of human war-gaming and computational modeling.

Human war-gaming has been used for centuries in a variety of ways, as discussed in a book by Peter Perla (1990). The perspective and observations made here are more narrow, reflecting certain types of military war gaming conducted by the Services and major commands, sometimes through war colleges (Downes-Martin, 2013).

Seminar War-Gaming

The goal of a war game is to provide insights by identifying hypotheses for testing by other means. There are three main challenges when using seminar war-gaming within military organizations to explore strategic nuclear deterrence.

First, unlike tactical conventional kinetic warfare, there is no long history of understandable results with credible statistically valid data for activities related to strategic nuclear deterrence. War-game adjudicators therefore have no rules determining the possible outcomes between protagonist players’ decisions. The second challenge stems from the first in that the need to develop rules at the time means that the adjudicators are de facto decision makers or players—even dominant players—something very different from their ostensible role as impartial referees. This suggests that war games dealing with strategic nuclear deterrence should collect data and information from adjudication teams as from traditional player cells. This is not usually possible because it would mean additional and time-consuming overhead, making it difficult to have an effective game within the usual one-week time period allocated by major commands for a war game.

A third challenge is that decisions made during game play are probably poor proxies for decisions that even the same players would make in real life.8 Fortunately, strong evidence from psychological research, as well as observation of games, indicates that their beliefs about a situation and their reflexive decision-making styles and preferences are more stable, even when they are confronted with credible evidence.9

________________

8 Jervis (2006, pp. 3-52); Wilson (2002); Pronin (2007); Nisbett and Wilson (1977, pp. 231-259).

9 Ross and Anderson (1982, pp. 129-152); Ross et al. (1975, pp. 880-892); Anderson et al. (1980, pp. 1037-1049).

Observation 3-2. Effective War-Gaming. It is more fruitful to design war games to understand player beliefs and perspectives, than to treat decisions within games as reliable information. The focus should be on the reasons for decisions, the messages sent and received, and the interpretations and misinterpretation of messages.

If these reasons are understood, then it should be possible to embed the underlying belief systems in models, simulations, and analysis for subsequent research (see also the section on synthesis). Seminar gaming is also conducted in other settings, such as civilian think tanks. The purposes are then different, as are their challenges. In some cases, members of the adjudication team may reflect deep knowledge (sometimes from prior real-world experience) regarding how decision makers would reason and about possible political and economic consequences of decisions not so evident to more typical adjudicators. So also for members of the country teams. Even so, the games are likely to provide better insights about factors, considerations, and beliefs than about what decisions would actually be.

Lessons To Be Learned from War-Gaming

War games as practiced at the Air University and the Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC) in recent years have had some severe limitations. Annual end-of-the-year Air War College and Air Command and Staff political–military games have often not had the objective of representing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) play. Controllers have often outlawed early use of WMD because it would stop the game, thereby ruining the opportunity for participants to go through the learning of routines that are the purpose of the games. This may have communicated the wrong lessons on WMD play because of artificial restraints.

War games involving nuclear exchanges conducted by AFGSC may err in the opposite direction. These exercises usually begin with early use of nuclear arms and do not include decision makers who have political or diplomatic roles. Each exercise thus is a walk up the escalation ladder without remedy to diplomatic or political means of arresting the conflict. These games have also omitted use of chemical and biological weapons in conjunction with nuclear employment, even though possible U.S. adversaries have a combination of such WMD assets.

AFGSC games are designed to start with early nuclear use. Such games avoid the problems of the Air University games because nuclear weapons employment is not arbitrarily prohibited. Indeed, the games are designed to acquaint participants with the nuances of nuclear warfare. However, the lack of a means of achieving a diplomatic end to such conflict in games may lead participants to the dubious belief that they can play nuclear chess. This remains highly speculative since there exists no historical record by which to judge. There is also no way to know if real decision makers in actual future crises and conflicts would act in reality as they act in games.

Caveats. War gaming must be integrated with other methods of inquiry and analysis since such war games by their nature do not prove or validate anything; any specific war game is a single trajectory through the space of possible scenarios defined by the interactions of all players in a game. Even the broader insights gained from post-game “hot washes” discussing both a particular game and what might have been must be regarded as tentative. That said, they can be quite valuable. Further, players learn a great deal about the relevant strategic “chessboard.”

Significance

Computational experimentation systematically harnesses a causal model of a phenomenon to conduct “experiments” over much of the model’s operating domain, generating substantial “data.” In some problem domains (e.g., in some engineering applications), the model may be validated, in which case the data can treated as empirical. More relevant to this study is computational social science in which the model in question is afflicted with uncertainties of two primary types: (1) parametric (i.e., input uncertainty) and (2) structural (i.e., uncertainty about the model’s content, such as completeness of its variables and the algorithms by which they interact).

Computational modeling will be discussed primarily in later sections relating to knowledge and theory development, but its data-generating role has become important with the advent of new technology, computer power, and conceptual approaches to analysis. This section discusses the vexing and cross-cutting problem of validation. Some of the points apply more broadly to validation of qualitative models as discussed in the next section.

Validation

Given the uncertainties typically associated with social-science computational models, a fundamental question is how they can be “validated” and what that should mean. A modest but thoughtful literature exists on this subject.10 It is inappropriate to see the models as “predictive,” as are models in the physical sciences

________________

10 See McNamara et al. (2011) and Bigelow and Davis (2003), which discuss validation for an analogous class of computational exploration. For results of an National Research Council (NRC) workshop, see National Research Council (2011b) and the unedited proceedings at http://sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/BOHSI/DBASSE_071321. An earlier NRC report discusses the different classes of uncertainty (National Research Council, 1997).

and engineering. Even so, exploration with such models can yield valuable insights. A natural and common rejoinder is, What good is a model if it can’t predict? How can the insights allegedly gained be valid? The answers begin with the observation that qualitative models have long been useful in all walks of life. For example, they may characterize the system, its parts, and the ways in which the parts interact with each other and the external environment. Even if the consequences of the interactions depend on unknown at-the-time details, the models may provide a structure for understanding the system and adapting to developments.

The word “may” applies because the model must be sufficiently solid “structurally,” and there must be some understanding of the range of plausible values for the variables within it.11 That is, the model must incorporate the most important variables at work—the right “factors.” Also, the model must convey a roughly right sense for how the factors affect system behavior. Fortunately, and despite their notorious shortcomings, experts in a given subject area usually have a strong sense of what variables matter and some sense about how they interact qualitatively.12 It is possible to “validate” their judgments by, for example, consulting different experts; conducting case studies to see whether the variables that they identify appear to have been important and whether other variables had been omitted; and evaluating the qualitative theories logically.

Caveats. Computational experimentation can be a good source of tentative insight about subtle possibilities, including possibilities against which deterrent strategies should hedge. If the models have sufficient structural validity and uncertainties can be bounded, exploratory analysis can yield nontrivial insights. Those, however, must then be assessed separately, as are, for example, potential insights from war gaming or experience.

FRAMEWORKS AND QUALITATIVE MODELING

In this section, we start with two subsections providing frameworks for thinking about deterrence and assurance. The subsequent subsections then describe particular qualitative methods for modeling or building theory.13 Some of these discuss qualitative aspects of what are more typically seen as quantitative methods.

________________

11 A model can be useful even if based on assumptions known to be false. For example, a useful rational-actor model may claim that behavior will be as though reasoning followed rational-actor prescriptions (an argument first made by Milton Friedman).

12 See Tetlock (2005 and earlier works).

13 Whether a model is qualitative or quantitative is murky in both theory and practice. Included here as qualitative are models that may use numbers that are merely mapped from subjective measures such as “low” and that emphasize problem structure and logic rather than computations.

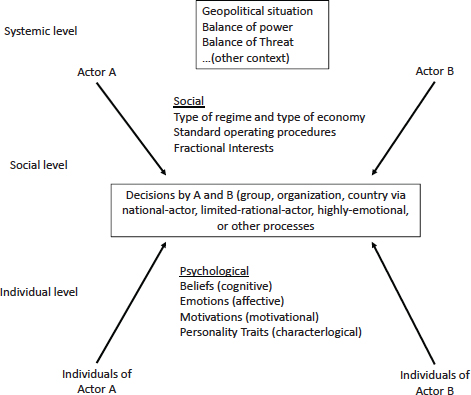

Deterrence and assurance depend fundamentally on psychological matters. Those are often strongly affected by “objective” situational considerations, such as geography and relative power. However, to be deterred or assured involves a state of mind. As discussed in more detail in Appendix D, which draws on a rich multidisciplinary literature, it is useful to have a broad framework for discussing such issues.14 The framework in Figure 3-2—for the simplified case of actor A and actor B—highlights a number of important concepts. First, the decisions the actors make (box in center) occur in an “external level” of context that includes the geopolitical situation, the relevant balances of power and threat, and so on. Second, decisions are ultimately made by some decision unit that may be a predominant individual, group, organization, or country and that may arrive at decisions based on any of a variety of processes characterized by rational-actor, limited-rational-actor, highly emotional, or other labels.

As if this were not enough complexity, the decision units of A and B are influenced by (note left column) systemic-, social-, and individual-level considerations. Here “social” includes type of regime and political system, standard operating procedures, factional interests, and related social psychology. “Individual-level” refers not just to the idealized thinking of the economic rational actor, but to psychological considerations such as beliefs, emotions, motivations, and personality traits.

Finding 3-2. Psychological Framework. Deterrence and assurance are largely psychological concepts. Thus, a proper evaluation of proposals for them will rely not only on the balance of military forces but also, whenever possible, on an understanding of the mindset and decision making of the adversary or ally.

As a corollary, the modern concept of “tailored deterrence” should be devised accordingly. As discussed at more length in Appendix D, a key element of this is how “messages” are passed and interpreted between or among parties (“messages” may range from diplomatic exchanges to signals accomplished with military or other actions). A substantial base of research describes just how complex and subtle such communication matters often are.

Finding 3-3. Tailoring Key Messages. To elicit the intended response, it is important for the sender to have methods and tools that can detect opportunities and send messages tailored to a recipient that is open (willing and able) to make a

________________

14 As discussed in Appendix D, the construct uses the levels of analysis of Waltz (1959), alternative images of decision making introduced by Allison (1969) and supplemented by Post (2003), and ideas from, for example, Campbell et al. (1960) and Kegley and Witkopf (1982) among others.

FIGURE 3-2 A broad framework for thinking about human decision making.

response based on available information rather than on motivational, affective, or cognitive biases in a deterrence or assurance situation.

This finding means that the deterrer needs to diagnose the situation, identifying the adversary’s decision unit and elements within it, understanding when one or more elements is likely to be open or closed, what might be causing “blockages,” how channels could be opened or open channels found, how messages of different types will be interpreted and how the likelihood of correct interpretations can be increased. Appendix D includes a relatively simple heuristic method (requiring analytic artistry, of course) for thinking through such issues.

Complex Adaptive System Theory

Figure 3-2 provides a kind of conceptual framework. An analytically richer scientific framework is provided by the theory of complex adaptive systems (CAS). CAS are usually described as hierarchical or nearly hierarchical collections of interacting entities that are adaptive in responding to each other and the external environment. Macroscopic system characteristics may “emerge” as a result of the interactions. Although CAS theory is quite general, it has been strongly motivated by such biological systems as the human body with its cells, tissues, organs, and functional systems. Most interesting social systems are examples of CAS, including a system of state and nonstate actors interacting in crisis.

A famous characteristic of complex adaptive systems is that—in some circumstances—small changes can have large and essentially unpredictable effects, sometimes with the system moving into one of two or more alternative states, to include peace or war. Describing a system in crisis this way is different from using a deterministic model that sees inexorable and predictable outcomes.15

CAS theory is a natural paradigm for work on deterrence and related matters and even for research on military matters more generally. Earlier NRC studies have urged DoD’s modeling and analysis to embrace the CAS paradigm (National Research Council, 2006). Doing so should also be part of the basic education of analysts seeking to describe or understand phenomena such as deterrence.16 Complexity thinking affects many of the other sections of this report, including that on computational modeling.

Caveats. As with many “new” and important subjects, CAS research is sometimes afflicted with breathless popular accounts, amateurish attempts to apply its concepts, and exaggerated claims about the usefulness of related models and the validity of their predictions.

The subject of deterrence is both complex and “soft” because it is about the thinking and behavior of people influenced by myriad interacting factors. Qualitative system modeling can be quite fruitful in understanding situations and evaluat-

________________

15 Books by pioneers are still especially illuminating (Holland and Mimnaugh, 1996; Gell-Mann, 1994). Some texts on CAS and agent-based modeling are Bar-Yam (2003) and North and Macal (2007).

16 See Robert Jervis on applying complexity theory to war-and-peace issues (Jervis, 1997a,b).

ing strategies.17 It can have many of the virtues of system modeling generally: (1) representing the “whole,” (2) characterizing influences, (3) representing interactions and feedback effects, and (5) conveying a coherent albeit complex story. In contrast with many quantitative models, however, these do not purport to predict or forecast—something arguably beyond the pale in the presence of deep uncertainties, as discussed later in the analysis section. The following subsections discuss three classes of qualitative model.

System Diagrams of System Dynamics, Bayesian Nets, and Influence Nets

MIT-style system dynamics is more fully described in a later section under computational modeling, but a key element is its use of causal-loop and stock-flow diagrams that convey a “system map” or “system view.”18 Somewhat analogous “influence diagrams” stemming from Carnegie Mellon research by Granger Morgan and Max Henrion serve similar purposes.19 System Dynamics is especially good at representing dynamical developments in systems with feedback loops. The Morgan-Henrion style has advantages for uncertainty analysis, multiresolution modeling, and decision aiding.

Other approaches using diagrams for visual modeling are Influence Nets and Timed Influence Nets, which stem from earlier work in Bayesian inference networks and related influence diagrams (with a different meaning of the term).20 Belief networks and related influence diagrams are directed graphical representations for models of probabilistic reasoning and decision making under uncertainty. They capture important relationships among uncertainties, decisions, and values. Applications of Bayesian-net and influence-net methods abound, many of them in risk-related subjects and some related to national security (Caswell et al., 2011). Bayesian-net analysis requires a great many input assumptions such as conditional probabilities. Influence nets use an approximation that greatly reduces this

________________

17 The committee considered quantitative political science and was briefed on recent interesting work related to nuclear matters. However, such research has limited value for its purposes because the historical data are and hopefully will remain sparse, and such work is usually about correlations, not the causality that decision makers often care about. Approaches that combine in-depth case studies and quantitative analysis would probably have more potential (Sambanis, 2004), as concluded also in a study of social science for understanding intervention operations (Davis, 2011).

18 Sterman (2000) is a text. Specialized software tools include STELLA (from ISEE Systems) and VENSIM (from Ventana Systems, Inc.). A broad discussion of system thinking is in Senge (2006).

19 See Morgan and Henrion (1992), a textbook on uncertainty analysis. The associated software is Analytica, developed and sold by Lumina Corp. Its use of the term “influence diagram” is different from some decision-analysis subdomains, where diagram nodes have probabilistic meanings.

20 A tutorial is available from the vendor for Netica, one of the tools available for such work at http://www.norsys.com/tutorials/netica/nt_toc_A.htm. A simple description from an authoritative volume is in Schachter (2007).

burden. An extension to “timed influence nets” has been used for some years in work at George Mason University, including simulation of crisis developments and deterrence.21

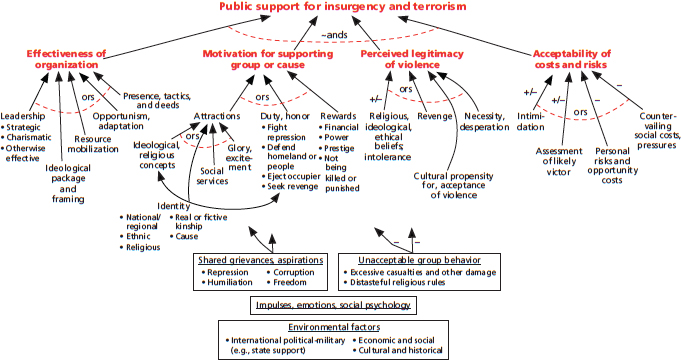

Factor Trees, Cognitive Maps, and Cognitive Models

Recent DoD-sponsored research introduced deliberately simpler diagrams, factor trees, which show the factors influencing something of interest at a slice in time, such as whether an individual will become a terrorist or whether a population will support an organization that uses terrorism. 22 Factor trees have proven effective for interdisciplinary discussion involving social scientists, officials, and military officers. They have been used in both unclassified and highly classified work. Factor trees can be turned into modular computational models that exploit more social science knowledge. However, because of uncertainties, they should be used for exploratory analysis, as described in the later section by that name, rather than forecasting.23An example, Figure 3-3, shows a factor tree for public support for insurgency and terrorism. The structure of this qualitative model was developed in one project and then subjected to validation testing in a study using new case histories involving al-Qaeda, the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (known by its Kurdish acronym, PKK) in Turkey, and the “Maoists” in Nepal. The validation testing was encouraging; it led to modest refinements and sharpening but nothing new structurally.24 The factor-tree approach should be directly useful in modeling deterrence and assurance issues.

Other qualitative diagram-based methods also deal with the thinking of individuals and groups. One method is cognitive mapping, as in the work of Robert Axelrod25 and subsequent efforts.26 A different kind of cognitive map appears in several strands of British work, including some that use such qualitative extensions of game theory as hypergames and drama games, which apply to problems involving confrontations and misperceptions. Participant may effectively be “playing

________________

21 See Levis et al. (2010) and earlier work referenced therein. Some of the Wagenahls-Levis work supplemented human play in war games at the Naval War College. SAIC (now Leidos Corp.) has developed proprietary tools called SIAM and Causeway for applications to government and industry, including crisis simulation work. An overview is available at http://www.inet.saic.com/inet-public/inet-intro.htm.

22 Davis and Cragin (2009).

23 Davis and O’Mahony (2013).

24 Davis et al. (2012).

25 Axelrod (1976).

26 The term “cognitive map” has many meanings with related streams of literature. It did not seem appropriate to discuss most of them here.

FIGURE 3-3 Factor tree for public support of insurgency and terrorism. SOURCE: Davis et al. (2012), adapted with permission by the RAND Corporation.

different games” and thus not even be sharing the same “gameboard,” emotions, and other complications—all relevant to deterrence research.27

More specific to deterrence, simple qualitative cognitive models expressible in diagrams and hierarchical decision or outcome tables have been used to understand the potential reasoning of adversaries such as Saddam Hussein in 1990-1991,28 Kim Jong Il in the mid-1990s, and terrorist leaders in recent times. These can aid coherent discussion of different ways in which adversaries may reason and aid development of related hedged strategies. Such hedging is important because best-estimate assessments of adversary thinking have often been quite wrong (a problem highlighted in Chapter 2).29 Such cognitive models can be informed by a combination of strategic thinking, personality profiles, as discussed later in this chapter and Appendix E, and additional inputs from regional/cultural experts.

Caveats. As with other methods, the value of qualitative modeling depends on the particular modelers and analysts, their access to relevant information, and exposure to peer review. Considerable knowledge and sophistication are necessary, even though some of the methods appear simple.

Game theory has long been important background for strategic thinking and practice with the basic concepts providing insights and language, such as Prisoner’s Dilemma or Chicken. These are useful even in real-world problems that are far more multidimensional and otherwise complex than can be dealt with convincingly by mathematical game theory. The committee does not review game theory here, instead regarding it as part of the baseline of methods. As discussed in Appendix D, however, it is useful to highlight certain advances in qualitative game theory that are valuable and simple enough to be understood and used, if only for background. Appendix D illustrates these by discussion of advances in the 2 × 2 “ordinal” game in which players have only two strategies and four possible qualitatively expressed outcomes to consider. This is by contrast with having more options, quantitative evaluations, and the need to make sometimes tricky mathematical calculations.

The primary innovations with significant value for drawing insights include using (1) sequential games in which the sides alternate in their moves until play stops and (2) allowing for asymmetric and perhaps incorrect information. In contrast with traditional game theory, results are seen (realistically) to be very dependent

________________

27 See British work (Bennett, 1985), including some applied to understanding and succeeding in operations other than war (Howard, 1999).

28 These grew out earlier work that built massive “analytic war games” with optional agents for decision making by U.S. or Soviet leadership. One conclusion was that the cream could be skimmed in representing adversary reasoning with drastically simpler qualitative models.

29 See National Research Council (1997), which drew on previous work (Davis and Arquilla, 1991).

on where the game begins, what sequencing occurs, and who has the “move power” to end the game. It follows that game outcomes include some worrisome situations that are not the familiar Nash equilibria of static game theory: they reflect dilemmas analogous in significance to, say, the Prisoner’s Dilemma or the game of Chicken. Game theoretic methods are valuable not only because of their insights but because, despite their simplicity and unpretentiousness, they add important aspects of realism that can readily be communicated and learned.

Earlier discussion covered some of the same tools but emphasized their qualitative-modeling aspects. Here the discussion is about computational capabilities.

System Dynamics, Bayesian Nets, and Influence Nets

MIT-style System Dynamics, mentioned above, was introduced about a half-century ago (Forrester, 1963, 1969, 1971) and is well described by a modern textbook with examples and problem sets (Sterman, 2000). It was remarkable in part for taking on “soft” social problems of great significance and bringing to bear mathematical and computer methods familiar from other disciplines. One stumbling point was Limits to Growth (Meadows, 1974), a book that was contentious for both good and bad reasons. The book and the related controversy, however, stimulated constructive counterstudies and considerable progress in understanding how to use model-based analysis and how to improve the modeling itself (Greenberger et al., 1976). A 30-year retrospective is a well-regarded cautionary piece about the potential for societal “overshoot” due to the interactions between human development and other matters such as sustainability.30 System Dynamics has been used extensively over the years and the approach remains vibrant. Other studies have used somewhat similar methods but different modeling tools.

A good deal of computational modeling has been used for defense work, much of it DARPA-funded science and technology.31 Some has dealt with the road from crisis to conflict and escalation, as in work briefed to the committee by Alex Levis and Kathleen Carley from George Mason and Carnegie-Mellon universities. They used multimodels that combine timed influence nets, agent-based modeling, and system dynamics. Somewhat analogous multimodeling research is ongoing at other universities.

________________

30 The Australian government’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization published a balanced review that compares actual developments over the 30 years with scenarios examined in the original work (the work held up rather well).

31 See Popp and Hen (2006).

Caveats. If studies involve major uncertainties, then models should be used for exploratory analysis, as discussed in the later section on the subject, rather than using just best-estimate cases and some excursions. Another caution is that the models in question often have buried structural shortcomings, as in assuming independence of events and ignoring some nonlinear effects. Finally, it is not customary as yet for such models to undergo the substantive peer review that would be necessary in strategic applications. So far, studies have often been better in their computer science than in the depth of their social science. Hopefully, that will change and there are great opportunities to be exploited.

Game-Structured, Agent-Based Modeling

Example from the 1980s

Lessons can be learned from a game-structured simulation that was developed in the Cold War as the RAND Strategy Assessment System (RSAS).32 This was a global analytic war game covering conventional war through general nuclear war. It allowed for independent decisions by NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and individual nations such as Britain and France with their independent nuclear deterrent. Human teams or models (agents) could be used interchangeably.

Rather than trying dubiously to “optimize,” the agents used heuristic artificial-intelligence devices. Higher-level models drew on escalation-ladder structures and the current and projected status of combat and conflict levels to make decisions. Operational war plans were modeled with what in artificial intelligence circles were called branched scripts (what a commander would call branches and sequels).

The RSAS had alternative versions of the top-level agents to embody different “mindsets.” This innovation was significant because then, as today, experts argued about how the sides’ leaderships would reason and act. Further, no one knew. In stereotype, one Red model was a determined “warfighter” reflecting Soviet military doctrine; another reflected the more pragmatic image many Sovietologists had of political leadership. Both models intended, however, to make rational decisions. Thus, the agents departed from their stereotypes: The warfighter might compromise and the “pragmatic” model might escalate.

________________

32 See Davis and Winnefeld (1983) and Davis (1989). “Game-structured” means that the model was organized around decision-making entities (agents) as in a human war game. One simulation run was analogous to a single human war game. Only some game-structured models are “game-theoretic.” For example, some combat models have the simulated commanders allocate their air forces and even ground forces so as to optimize simulation results, taking into account that the adversary model might be trying to do so also. See Hillestad and Moore (1996). Such methods are valuable for analysis dominated by physical phenomena such as conventional combat.

As one relevant example from 30 years ago, RAND conducted experiments with limited nuclear options. Blue had a model of Red, which had a simpler model of Blue, which had an even simpler model of Red. In some cases, Blue would use a limited nuclear option to “re-establish deterrence,” as in NATO doctrine. Red, however, would perceive the act as Blue having initiated nuclear war and would immediately engage in all-out general nuclear war. In other runs, depending on details and model, Red would de-escalate or continue even though not having “won.” This study cast doubts on NATO’s concepts and plans for nuclear use shortly before collapse of its conventional defenses (Davis, 1989), suggesting that such late use might be especially ill-advised. The insights were similar to those from sensitive high-level U.S. war games conducted in the 1980s (Bracken, 2012). Another observation drawn by RAND was that many (most?) of the insights to be gained can be obtained with simpler models and even simpler methods, such as described elsewhere in this report (e.g., qualitative cognitive modeling).

Observation 3-3. Alternative Adversary Models. Because of irresolvable uncertainties, disagreements among experts, and the need to open decision maker minds to non-best-estimate possibilities, it is important to use alternative adversary models rather than relying on best estimates, however carefully developed.

This finding reinforces the need for leadership profiles as discussed later and in Appendix E, but with some tension because it emphasizes having alternative assessments.

Modern-Day Options?

Analogous game-structured computational models could be built today with more advanced technology.33 The value of such work would still depend on the models representing deep knowledge of political and military issues and of human and organizational decision making. They would be even more complex because of needing to represent economic instruments of power, the interaction of multiple nuclear powers (some with chemical and biological weapons as well), and the consequences of precision weapons and the cyber and space domains. The classic escalation ladder could no longer be used as an organizing principle because the types of war have become intermingled. Such an enterprise would be a daunting and sizable undertaking, as was the 1980s effort, which stemmed from

________________

33 Relevant technologies include agent-based modeling, multimodeling that combines models of different types (Fishwick, 2007), more powerful graphics, and mechanisms for exploratory analysis.

a recommendation of the Defense Science Board and was funded by the Secretary of Defense’s Office of Net Assessment.34

Caveats. If one were contemplating a modern-day construct, it should be noted that, while the RSAS was technically successful, afforded insights, and became the basis for a number of studies, it proved too difficult for inside-government work, despite heroic efforts to make it comprehensible and modular (Hanley, 1991). The reasons included the sophistication needed, personnel turnover, and something more subtle: Effective use required independent thinking against the grain of conventional wisdom and with not too much respect for “best estimates.” Such thinking is often not the strong suit of military or other government organizations.

Modeling of Limited Rationality

A cross-cutting issue in computational modeling (and, also in the qualitative modeling described earlier) is the type of reasoning assumed. Regrettably, too many modern computational models give their agents simplistic rational-actor algorithms. Fortunately (see also Chapter 2), the rational-actor model has been embellished and other steps taken to go beyond it by focusing on, for example, perceptions rather than reality, recognizing that utility functions (to the extent that utility functions exist and are stable) vary across individuals and groups and are often poorly understood by others, that individuals have only limited rationality, that agents in multiagent situations will assess their power positions relative to others and adjust their positions accordingly to improve their overall prospects, and that risk aversion is an important consideration.

One element of such work has been to represent rather predictable behavioral considerations demonstrated in experimental psychology35 and discussed by some political scientists. 36 The most well-known consideration is described as “prospect theory,” which asserts that a decision maker evaluates options differently depending on whether he is in the “domain of losses” or the “domain of gains.” This explains why deterrence is easier than compellence: The perceived value from possible gains is seen as less than the perceived value of maintaining gains already achieved. Some such work is cross-cutting and discusses how rational-choice theory can perhaps accommodate prospect-theory effects (essentially by recognizing that utilities are

________________

34 One modern game-structured simulation is the British Peace Support Operations Model (PSOM), used to support operations in Afghanistan. It was not designed to deal with nuclear issues or deterrence. See Body and Marson (2011) and accompanying articles.

35 The work was pioneered by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. See Kahneman’s Nobel address (Kahneman, 2002) and a recent accessible synthesis (Kahneman, 2011).

36 See, for example, Jervis et al. (1985).

not stable and correcting for predictable situation-dependent effects, including risk-taking).37

In contrast to thinking in the 20th century, it is now increasingly recognized that the rational-actor model is not always appropriate, even as a normative standard. That is, it is not only not descriptive; it is sometimes not appropriate. This stems from recognition of the value of “naturalistic,” heuristics-driven human adaptivity using cognitive short cuts.38 Some of the literature discusses the need to synthesize the perspectives of rational-analytic and naturalistic reasoning, emphasizing that both classes have their place (Davis et al., 2005). Someone in the heat of battle should rely on heuristics, while someone in peacetime should take the time for more deliberate and rational-analytic reasoning. However, the heuristics should reflect knowledge informed by rational analysis and rational analysis should allow for creative thinking, which is often intuitive. This balanced perspective has recently been described by Kahnemann (2011), dissipating earlier controversy between the heuristics-and-biases and naturalistic schools.39

Observation 3-4. Modeling and Limited Rationality. Both qualitative and computational modeling in support of deterrence and assurance should incorporate aspects of “limited rationality” and even more strongly emotion-driven behaviors.

ANALYSIS METHODS FOR DECISION AIDING

The committee did not review methods seen as part of the baseline.40 A number of advancements, however, are relevant to modern-day analysis of nuclear-force issues.41 What follows highlights four methods with direct implications for deterrence and assurance studies. They deal with (1) leadership profiling), (2) analyzing

________________

37 One often-cited paper was specifically undertaken to cross the intellectual divide between rational-choice and behavioral-theory perspectives (Bueno de Mesquita and McDermott, 2004). The article appears in one of two special issues of Political Psychology devoted to related matters (Volumes 2 and 3 in 2004).

38 See Klein (1999, 2006a,b), Gigerenzer and Selten (2002), and Suedfeld et al. (2003).

39 See Bueno de Mesquita (1997); National Research Council (2011a) and references therein, and DoD work with the Senturion model (Abdollahian et al., 2006).

40 Examples include operations research, systems analysis, statistics, and classic game theory as described in, for example, Powell (2005), Washburn (2003), and Poundstone (1992). The first two are texts; the last describes game-theory history and its implications for arms races.

41 One example showed attacking mobile launchers has more leverage than intercepting missiles in flight (Shaver and Mesic, 1995). A second example showed that optimizing resources to protect infrastructure has a different character when the infrastructure is large and attackers are limited (Brown et al., 2005). Third, optimizing to assure resilience involves sequential non-zero-sum games with three phases: (1) initial defense preparations, (2) an attacker observing the preparations, and (3) the postattack adapting with what remains.

receptivity of adversaries, (3) exploratory analysis and robust decision making, and (4) strategic portfolio analysis. The method of sequential ordinal games discussed earlier (under qualitative game theory) is also relevant.

Motivation Approaches

As discussed in Chapter 2 and earlier in this chapter, deterrence and assurance depend strongly on the psychology of those to be influenced. It follows that we should be quite interested in developing profiles of both adversaries and allies. What profiling methods are available? As discussed in considerable length in Appendix E, drawing on substantial literature, two distinct approaches exist (each with many variations). The first may be seen as top-down and is based on developing a subject’s psychobiographical background and then using the insights to assess current circumstances. The second approach may be seen as bottom-up and draws on more proximate evidence to infer characteristics such as openness and risk-taking propensity. This second approach emphasizes quantitative content analysis, as also discussed briefly early in this chapter. Methods have been developed and substantially refined that allow significant inferences to be drawn from, among other things, speeches, interviews, news conferences, diplomatic exchanges, and (in principle) classified documents. Changes in the inferred behavior over time can be particularly valuable. Appendix E describes both approaches in moderate detail and illustrates them by working through the example of Saddam Hussein, on whom a great deal of peer-reviewed research has been published illustrating the approaches.

Selected Observations

When decisions are made, psychological and social processes act as causal mechanisms of cognition, emotion, and motivation, which Ledoux (2002) calls the “trilogy” of the mind. Contemporary neuroscience focuses on how the brain’s physiology generates these mechanisms (Schafer and Walker, 2006: 49, n. 2; see also Ledoux and Hirst, 1986). In this model, the brain sends and receives messages along neural networks containing information in the form of cognitions, emotions expressed as feelings, and motivations directing action (Ledoux, 2002).

Learning and adaptation reflect such stimuli and information stored in the brain: they are emergent properties of human decision-making. Beliefs and belief systems, in turn, reflect these properties as higher-level and relatively conscious knowledge networks that are activated and modified by such environmental stimuli as threats or promises, These knowledge networks are linked with more primitive,

lower level, unconscious elements of the trilogy outside the full awareness of the decision maker (Schafer and Walker, 2006, pp. 29 and 30). Observing the operation of these networks is difficult even if one has access to the decision maker and, certainly, if one does not (Schafer, 2000; Schafer and Walker, 2006).

While it is difficult to access and then assess the decision-making processes of a single leader, it is not impossible. The “at a distance” approach in political psychology infers subjective thoughts, emotions, and motivations of leaders and groups from the language that they use to express them. The assumption is that these sentient features of an individual or group can be modeled and tested (measured repeatedly) for accuracy with the aid of this information. These efforts yield a deeper understanding of the system of interest and its causal mechanisms. They may enable some predictions about future behavior under different assumptions about its evolving relationship to other objects. Fortunately, much can be done, as described in Appendix E.

Finding 3-4. Tailored Deterrence. The methods of content analysis and leadership profiling in conjunction with other methods have the potential to help meet requirements of actor-specific knowledge for a strategy of tailored deterrence. An alliance among content analysis, leadership profiling, abstract modeling, and gaming and simulations as a suite of methods is possible in order to solve the complex problems associated with studying the decision-making dynamics of single groups and multiple autonomous actors as decision units.

Understanding and Affecting Receptivity to Messages

As discussed earlier in “Content Analysis and Profiling,” an important aspect of tailored deterrence must be understanding whether and how adversaries and allies receive “messages.” The need to so has long been understood, but modern social-science methods provide a number of valuable ways to help. These are discussed in more depth in Appendix D, which includes a heuristic model (Figure D-2) that can be used artistically to diagnose the receptivity of the target, differentiating among different elements within the target, and to then identify priorities for “unblocking” channels when blocks exist (as is common). Although systematized and based on extensive theoretical and empirical scholarly research, the tactics and stratagems of the method relate well to real-world concepts familiar (if less systematically) to diplomats.

Exploratory Analysis and Robust Decision Making

With roots back to the early 1980s, a new approach to uncertainty analysis has evolved and been applied in many studies on defense planning, private-sector

strategic planning, and social problems such as climate change and water management.42 The approach deals pragmatically with deep uncertainty43 by better understanding which such uncertainties matter most and where it is feasible, affordable, and fruitful to build hedges into plans, to prepare for inevitable adaptations, or both. The approach calls for exploratory analysis and seeks strategies that will be effective in any of a broad range of futures, although not optimal for any one of them. The methods are highly relevant to deterrence, assurance, and related matters where uncertainties loom large.

The concept of exploratory analysis is seemingly straightforward. If one has a good model representing the problem, but with the variables highly uncertain, then to test strategy options, one should want to know how they would perform throughout the entire scenario space or case space implied by the uncertainties. This goes far beyond sensitivity analysis around a standard case. A good strategy is one that would likely do well for much of the possibility space. Such a strategy would exhibit “FARness”—that is, it would be flexible, adaptive, and robust in the sense that it could accommodate changes of mission or objectives, changes of circumstance, and adverse shocks.

Modern methods allow such exploration, especially if the model is designed with two or more levels of resolution, in which case broad and comprehensible exploration can be made first, followed by more selective exploration of individual issues in more detail. “Scenario discovery” methods have the computer search for regions of case space that are, for instance, favorable or unfavorable.

Caveats. The value of exploratory analysis depends on knowing the primary factors, bounding uncertainties, and making judgments about what portions of the possibility space to plan for (which might be constrained by budget, technology, or plausibility). Tendencies to treat quantitative versions of such analysis as rigorous should be resisted and details of such uncertainty-sensitive analysis should be kept “down in the ranks,” with higher-level discussions being simpler, more nearly qualitative, and unpretentious. The greatest value is in suggesting practical ways to cope with uncertainty with reasonable hedging and preparation for adaptation. If uncertainty analysis is obtrusive or complicated, it can become paralyzing or appropriately off-putting.

________________

42 See Davis (2014), a review (Davis, 2012), Lempert et al. (2003), and a website on robust decision making, http://www.rand.org/topics/robust-decision-making.html.

43 Deep uncertainties (a term apparently introduced by Kenneth Arrow) are those that cannot be treated fruitfully with probabilistic methods because, for example, we don’t understand the phenomena, we don’t know all the factors, or we understand the phenomenon and have the factors but not their distribution functions (Lempert et al., 2003). Deep uncertainty incorporates what has sometimes been called future-scenario uncertainty.

“Strategic portfolio analysis,” as the term is used here, is an approach to analysis with the following features:44 (1) a focus on aiding policy makers; (2) multiple incommensurate criteria, some of them soft and in tension; (3) visual displays facilitating qualitative and quantitative discussion and debate; (4) the ability to examine issues at different levels of detail, and (5) confronting deep uncertainty and, often, disagreement among policy makers, when establishing strategy and allocating resources.

It has a metaphorical relationship to financial portfolio analysis and is logically just another example of multiple-criteria decision analysis. Its character, however, is different from that of most such methods. It is much less about solving a mathematical problem (e.g., “optimizing”) than discovering—amidst strategic uncertainties and disagreements—acceptably balanced strategies that attend adequately to the multiple considerations, in part by hedging. In a defense context, criteria may include acceptable predicted results for test-case scenarios stressing different aspects of capability; dealing with various types of risk and up-side potential; and costs.

Decision makers see option comparisons expressed with policy scorecards showing how well the various options perform by different criteria. This is the level at which strategic decision is encouraged because, for strategic problems, it is seldom that there are well-defined a priori “weights” for the different criteria or that prudent decisions will correspond to taking linear-weighted sums. To the contrary, policy makers contemplate the assessments, ponder, discuss and debate with peers to “discover” their objectives and values. They think about balance and hedging because they must pay attention to all objectives. Further, they must deal with uncertainties and strong disagreements.45 Policy-maker review can include interactive probing to understand in more detail underlying assumptions leading to demands for refined options and criteria and guidance about balance. Such iteration can be rapid rather than requiring repeated extensions of lengthy studies.

It then becomes possible to construct a composite measure of option effectiveness. The de facto “utility function” involved may turn out be nonlinear and is a product of decision making rather than an input. Since it reflects prior iterative discussion, it can be very helpful in constructing better-crafted composite options attending to the multiple criteria. As an example for nuclear forces, a composite option might include adjustments in force structure, force posture (e.g., forward deployment or routine deployments), weapons mix, and changes of employment

________________

44 For highlights, see Davis (2014), which includes references to more detailed work and a related tool.

45 This type of thinking about “balance” was particularly evident in the speeches and actions of Robert Gates when Secretary of Defense.

strategy. These adjustments might be tested for deterrence in scenarios with different assumptions about circumstances and adversary mindset, and for deterrence with different assumptions about what allies find reassuring. New methods exist for considering a vast range of possible composite options and then filtering to retain those that could plausibly meet decision-maker criteria.

Consistent with the general emphasis on coping well with uncertainty and disagreement, cost-effectiveness analysis treats effectiveness and costs as uncertain. Further, it evaluates options using different “strategic perspectives” to highlight how disagreements do or do not affect the relative attractiveness of options. For strategic forces, such alternative perspectives may amount to different relative emphasis on, say, modernization, current operations, robustness of deterrence, reductions of weapons, regional stability, and nonproliferation objectives. Overall, the method is useful for integrative strategic analysis and debate. Its strengths are framing issues and providing insights about balance across multiple objectives, thereby influencing resource allocation.

Caveats. Some aspects of strategic portfolio analysis are familiar and seemingly straightforward. In practice, developing the appropriate structures to support vigorous strategic-level debate and decision is difficult—in part because it requires confronting sensitive uncertainties and disagreements, and raising options and considerations that are contrary to prevailing thought. Useful versions may be impossible without strong support from top policy makers insisting that that the sensitive matters be addressed. In the corporate world, this is sometimes accomplished with outside strategic consultant companies enlisted by top corporate officials.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR SYNERGY ACROSS TOOLS, METHODS, AND APPROACHES

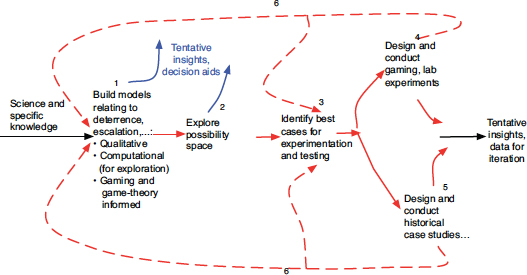

Opportunities exist for synergy among, for example, human gaming, qualitative and computational modeling, historical studies, and game theory—traditionally separate activities. A synthesis would improve the quality of knowledge. As an analogy consider that one lesson from the hard sciences and engineering when dealing with complex systems is that the model becomes the centerpiece of knowledge with experimentation used to test, falsify or affirm, and/or calibrate the model—but with no illusions about it being possible to base reasoning and decision making on experimental data per se because the necessary data cannot be obtained or maintained. The model must then become the workhorse for aiding decision. As a result, experimentation is designed to test the model wisely. Rather than squandering tests on circumstances for which the model can reasonably be expected to be accurate, the experiments are focused primarily where they might yield new information about serious inaccuracies, random instabilities, or magnitudes of effects.

FIGURE 3-4 Synthesis of modeling and gaming approaches.

Figure 3-4 illustrates a concept that could be brought to bear in advancing the analytic study of deterrence-related issues. Some of its elements have precedent, but—overall—Figure 3-4 suggests a radically different approach to inquiry. It assumes that