A CHANGING ARCTIC

The Arctic acts as an integrating, regulating, and mediating component of the physical, atmospheric, and cryospheric systems that govern life on Earth. It is also undergoing rapid climate change, the rate of which is projected to accelerate in coming decades (e.g., Serreze et al., 2000; Bitz et al., 2012; Kay et al., 2012; Jeffries and Richter-Menge, 2013). Surface air temperature increases in the Arctic in recent decades are about two to four times larger than observed in the midlatitudes, with evidence that the increase will continue (Overland et al., 2012, 2013). This “Arctic amplification” has been attributed to various complicated interactions between physical mechanisms (NRC, 2014), including albedo (solar reflectance) change due to sea ice and snowline retreat and latitudinal differences in surface energy radiation (e.g., IPCC, 2007, 2013; Francis and Vavrus, 2012; Pithan and Mauritsen, 2014).

The most obvious evidence for Arctic change has been the well-documented retreat and thinning of Arctic sea ice cover (e.g., Stroeve et al., 2012; Wadhams, 2012a,b; Overland and Wang, 2013; Perovich et al., 2013; IPCC, 2014). Between 1979 and 2013, the linear rate of decline of September ice extent was 13.7% per decade. The largest sea ice losses were documented in the Beaufort and Chukchi regions, particularly in the extremely low summer sea ice years of 2007 and 2012.1 Recent increases in surface ocean temperatures in the Arctic, particularly in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, are related to this sea ice retreat (e.g., Perovich et al., 2008, 2011). Mean surface ocean temperatures in the southern Beaufort Sea in August 2007 and 2012 were more than 2°C warmer than the August mean between 1982 and 2006 (Timmermans et al., 2013).

Warming upper ocean temperatures may lead to increased thawing of offshore and coastal permafrost (Shakhova et al., 2010; Portnov et al., 2013; Whiteman et al., 2013) and coastal erosion, which is exacerbated by sea ice loss and increased sea state, as well as sea-level rise (e.g., Jones et al., 2009b; Barnhart et al., 2011). Increased waves are already a feature of the Alaskan coastal zone (e.g., Barnett et al., 2012). Other known climate change manifestations in the Arctic include changing

_____________

1 See http://www.nsidc.org.

atmospheric circulation patterns and increased cloud cover, related in part to the reduced sea ice extent (e.g., Overland et al., 2013).

The feedbacks and transitions occurring in this region will have significant implications for biodiversity, human benefits from the ecosystem, and other important processes within the Arctic and global system (Nilsson et al., 2013). As the Arctic changes, larger areas are becoming more accessible for shipping, exploration, and resource development, which come with increased concerns for oil spills and other types of potentially harmful incidents that could impact U.S. waters. There have been a number of recent efforts that highlight the importance of the Arctic to national interests (e.g., Holland-Bartels and Pierce, 2011; NSTC, 2013; USARC, 2013; USCG, 2013b).

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE U.S. ARCTIC

The Arctic Research and Policy Act of 1984 (P.L. 98-373) defines the Arctic as “all United States and foreign territory north of the Arctic Circle and all United States territory north and west of the boundary formed by the Porcupine, Yukon, and Kuskokwim Rivers [in Alaska]; all contiguous seas, including the Arctic Ocean and the Beaufort, Bering, and Chukchi Seas; and the Aleutian chain.” U.S. Arctic waters north of the Bering Strait and west of the Canadian border encompass a vast area divided into the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). In general, the Chukchi Sea is underlain by a very broad and shallow continental shelf, whereas the Beaufort Sea has a relatively narrow shelf that drops into the deep Canada Basin. These seas are ice covered for much of the year but are increasingly experiencing longer periods and larger areas of open water, with the maximum area of open water occurring in mid-September (Jeffries and Richter-Menge, 2013). Much of this region is located north of the Arctic Circle, experiencing winter months with little to no daylight and summer months with up to 24 hours of daylight.

The Alaskan coastline north of the Bering Strait is sparsely inhabited. According to 2010 census data, the total population of the North Slope Borough was less than 8,000 persons.2 The largest coastal communities in the Northwest Arctic and North Slope Boroughs are Kotzebue and Barrow, which respectively have more than 3,000 and 4,000 residents. All other villages in the boroughs have populations of fewer than 1,000 residents. The indigenous culture is primarily Iñupiat along the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. The coastal and some inland communities rely extensively on marine subsistence resources, together with revenues from onshore oil development in the Prudhoe Bay area and commercial chum salmon fishing in Kotzebue Sound.

These seas are home to ecosystems with a wide diversity of marine life. Many marine mammals and seabirds migrate seasonally to the Chukchi and Beaufort areas, with some permanent resident populations of polar bears and seals. Owing to the rapid warming of the Arctic and the associated decrease in sea ice, significant changes are occurring in the habitat, range, and behavior of the marine species that inhabit these waters (CAFF, 2013).

The communities of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas have limited infrastructure and no deepwater ports. None of the communities have permanent road infrastructure connected to the main

_____________

2 See http://www.north-slope.org/departments/mayorsoffice/census_data_2010.php; http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/02/02188.html; http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/02/02185.html.

Figure 1.1 Location map of Alaska and the continental United States, and surrounding countries and water bodies. The red box shows the location of inset maps that are referenced throughout the report (beginning with Figure 1.2). Bathymetry, geopolitical boundaries, capitals, and select Alaskan cities are also shown.

highway systems or large communities in Alaska, although some communities are seasonally connected by ice roads. Instead, the communities are largely dependent on air and seasonal marine transport for the movement of people, goods, and services outside their regions. All coastal communities receive barge shipments during the summer and early autumn open water months. Industrial activities of the region include commercial fishing in Kotzebue, Port Clarence, and Norton Sound;3 the Red Dog lead and zinc mine north of Kotzebue; and oil and gas fields on the North Slope.

_____________

3 See http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=fishingCommercial.main.

Figure 1.2 Location map of Alaska and U.S. Arctic waters, focused on the Bering Strait, Chukchi Sea, and Beaufort Sea. Geopolitical boundaries, principal coastal communities, cities, and bathymetry are also shown. Map area corresponds to the red box in Figure 1.1.

INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES: OIL, GAS, AND SHIPPING

The global ocean has long been exposed to a significant quantity of petroleum hydrocarbons from natural seeps of oil and gas, marine oil transportation accidents, and operational discharges (NRC, 2003; Yakimov et al., 2007). The Arctic marine environment is rich in oil and gas. There are an estimated 30 billion barrels of technically recoverable undiscovered oil4 in the U.S. Arctic, which equals approximately one-third of the total resource found in the entire circum-Arctic region (Bird

_____________

4 “Technically recoverable” undiscovered oil refers to reserves that could be produced using current technology, without consideration of economic viability. “Economically recoverable” refers to the amount of technically recoverable oil whose price can cover costs of production (BOEM, 2011; also see http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2011/1103/).

et al., 2008). The subsurface Chukchi Sea Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) is estimated to contain 11 billion barrels of undiscovered economically recoverable oil and 38 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, while the subsurface Beaufort Sea OCS is estimated to contain 6 billion barrels of undiscovered economically recoverable oil and 11 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (at $110/barrel and $7.83/ thousand cubic feet of gas; BOEM, 2011). It is estimated that 80 to 90% of petroleum hydrocarbon entering the Arctic marine environment is from natural seeps (AMAP, 2008). Becker and Manen (1988) reported the presence of oil seeps in the coastal regions of Alaska and estimated submarine seepage to be approximately 1,000 tons/yr. As crude oil seepage has been estimated to be 600,000 metric tons/yr globally (Kvenvolden and Cooper, 2003; NRC, 2003), natural seeps may be among the most important sources of oil entering the ocean.

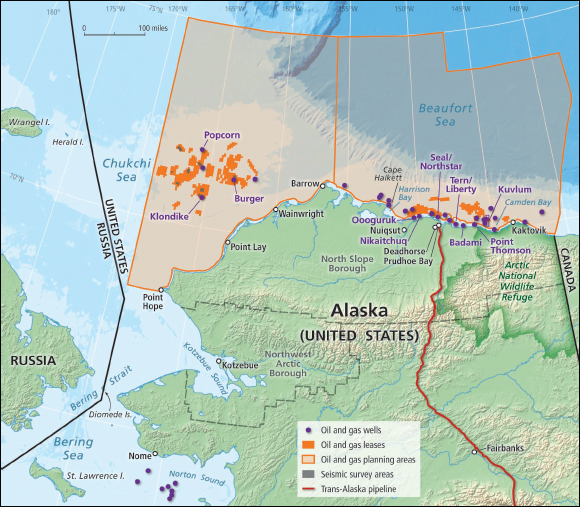

In the Chukchi Sea, most of the exploration activity occurs relatively far offshore (greater than 80-120 km), roughly equidistant from the villages of Point Lay and Wainwright (Figure 1.3). For this

Figure 1.3 Oil and gas planning areas in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. Oil and gas lease areas are shown in orange, with seismic survey areas shown in gray. Selected oil and gas wells, some in Alaskan state waters and some in federal waters, are shown as purple dots. Some coastal communities and cities are also shown.

region, most of the resupply and support vessel traffic is between the offshore and points of origin of the exploration vessels (e.g., Dutch Harbor, and/or Nome). Crew change-out and some resupply also take place through Wainwright and Barrow. In the Beaufort Sea, oil exploration is primarily located between Kaktovik and Cape Halkett, especially near Camden Bay, the Colville River Delta, and Harrison Bay. Beaufort Sea exploration is closer to shore (~15-30 km), between Kaktovik and Nuiqsut. As with the Chukchi exploration effort, vessels arrive in the Beaufort Sea by traversing the Bering Strait and Chukchi Sea and rounding Point Barrow or, to a lesser degree, via Canadian waters to the east. Additional material resupply, crew change-out, and other vessel traffic are routed between the exploration areas and Prudhoe Bay.

Most of the existing Alaskan North Slope oil production infrastructure is located within a 120×40 km area between the Sagavanirktok and Colville Rivers along the central Beaufort Sea coastline. Pipelines extend approximately 30 km farther to the east, to BP’s Badami and ExxonMobil’s Point Thomson projects. Of the oil fields in this area, the Northstar, Oooguruk, and Nikaitchuq fields are produced from offshore facilities, with buried pipelines transmitting oil to facilities onshore. Other facilities are along the coast or in nearshore waters connected by a causeway (e.g., the Endicott Development, which was built on an artificial island). The location of these fields and pipelines influences the risk faced by communities and biological resources. Many villages are located along the coast, in large part because these areas are used by a variety of important subsistence species, especially marine mammals and birds.

Exploration drilling in the U.S. Beaufort and Chukchi Seas OCS began in the early 1980s, with 20 exploratory wells drilled between 1980 and 1989. The first discovery of oil in the Beaufort Sea OCS came in 1983 at the Tern (Liberty) field, and the largest discovery to date was made in 1993 at the Kuvlum field. Northstar was the first field to be developed in federal waters in the Beaufort Sea (although the development area spans state and federal waters), beginning production in 2001 (Holland-Bartels and Pierce, 2011). To date, 30 exploration wells5 have been drilled in the Beaufort Sea OCS; only three of those were drilled since the mid-1990s.6 In the Chukchi Sea OCS, five exploratory wells have been drilled.7 All were drilled between 1989 and 1991, and several discovered hydrocarbons (USDOI, 2013).

Between 2008 and 2011, there were delays in additional exploration. In 2010, following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (see Box 1.1), Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar suspended proposed exploratory oil drilling in the Arctic.8 In 2011, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) conditionally approved Shell’s 2012 Exploration Plans for both the Beaufort9 and Chukchi10 Seas, and the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) permitted Shell to begin drilling

_____________

5 See http://www.boem.gov/uploadedFiles/BOEM/About_BOEM/BOEM_Regions/Alaska_Region/Historical_Data/OCS%20Wells%20Drilled%20by%20Planning%20Area%20-%20AK.pdf.

6 See http://www.boem.gov/uploadedFiles/BOEM/About_BOEM/BOEM_Regions/Alaska_Region/Historical_Data/Exploration%20Wells%20Beaufort%20Sea.pdf.

7 See http://www.boem.gov/uploadedFiles/BOEM/About_BOEM/BOEM_Regions/Alaska_Region/Historical_Data/Exploration%20Wells%20Chukchi%20Sea.pdf.

8 See http://www.doi.gov/news/pressreleases/Salazar-Calls-for-New-Safety-Measures-for-Offshore-Oil-and-Gas-Operations-Orders-Six-Month-Moratorium-on-Deepwater-Drilling.cfm.

9 See http://www.boem.gov/BOEM-Newsroom/Press-Releases/2011/press0804a.aspx.

10 See http://www.boem.gov/BOEM-Newsroom/Press-Releases/2011/press12162011.aspx.

in 2012. Drilling was limited to two surface holes, due to issues with readiness of their dome containment device as well as the lack of a fully compliant spill response barge. Despite further hurdles, including the grounding of the Kulluk drilling unit (see Box 1.1), Shell continued to pursue drilling activity in early 2013, focusing their drilling activities at the Burger prospect in the Chukchi Sea and near the Kuvlum and Hammerhead fields in the Beaufort Sea. In February 2013, Shell announced that it was halting further exploration activities until 2014, at which point it planned to drill in the Chukchi Sea only. In its most recent announcement on January 30, 2014, Shell again postponed its drilling activities, citing as its reason a decision by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals11 regarding a flawed environmental impact statement for lease sales in the Chukchi Sea.

Drilling operations in Arctic waters have been and continue to be highly controversial. The National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill (2011) noted that “[t]he stakes for drilling in the U.S. Arctic are raised by the richness of its ecosystems.” Many individuals and conservation organizations advocate a halt to drilling in the region. Their concerns are primarily centered around inadequate baseline and monitoring data, especially for sensitive and important ecological areas; limited infrastructure available to address oil spills; challenges presented by little daylight in winter, rough weather, sea ice, and remoteness; and a lack of effective methods for responding to oil spills (Oceana, 2008; WWF, 2010; Pew Charitable Trust, 2013). Some of these concerns are based on experiences and environmental impacts from previous oil spills in the region, notably the Exxon Valdez accident (discussed in Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 briefly describes four oil spills and marine transportation accidents that have relevance for the U.S. Arctic—the Exxon Valdez, Deepwater Horizon, Kulluk, and Selendang Ayu. These incidents are referenced throughout the report.

Large commercial vessel traffic through the Bering Strait to Alaska’s northern regions has typically been dedicated to servicing the nearshore and onshore oil production facilities on the North Slope, transporting zinc and lead from the Red Dog mine through its port on the Chukchi Sea, and delivering fuel, equipment, and supplies to coastal communities (Figure 1.3). However, the vessel traffic situation in the region has recently changed noticeably. There has been an increase in seasonal maritime traffic from increased oil and gas exploration, ship-based oceanographic research missions from a variety of nations (including some that are newer to Arctic research, such as South Korea and China), tourism vessels, and shipping of oil and other commodities from Russia through the Northern Sea Route (Arctic Council, 2009). These trends are expected to continue, with additional traffic potential from the development of large-scale mineral deposits in the Canadian and Russian Arctic and the development of new oil fields in the Alaskan OCS. More than 300 vessels transited the Bering Strait in 2012, up from approximately 260 in 2009, according to Automatic Identification System data.12 Of these, bulk carriers, tugs and barges, and research vessels constitute the largest categories.

_____________

11 Native Village of Point Hope v. Jewell, No. 12-35287 (9th Cir. filed Jan. 22, 2014).

12 Marine Exchange of Alaska, Record of Recorded Transits, Bering Strait, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012.

BOX 1.1 Select Oil Spills and Maritime Accidents of Interest

Exxon Valdez — On March 24, 1989, Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker headed for Long Beach, California, struck a reef in Prince William Sound, Alaska. The collision with the reef punctured 8 of the tanker’s 11 cargo tanks. The damaged tanker spilled approximately 10.8 million gallons of North Slope crude oil. It was estimated to be carrying approximately 53 million gallons when it was wrecked. At the time, it was the largest single oil spill in U.S. coastal waters. Oil from the spill reached nearly 2,100 km of coastline, approximately 200 of which were considered heavily oiled. The other 1,750 km were either lightly or very lightly oiled. The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council estimates as many as 250,000 seabirds, 2,800 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 bald eagles, and 22 killer whales died as a result of the incident.

Deepwater Horizon — On April 20, 2010, there was an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil platform as it drilled the Macondo Well in the Gulf of Mexico. The uncontrolled oil flow from the wellhead led to a release of about 205 million gallons at a depth of ~1,500 m. The DWH oil spill is, to date, the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. Although a final Natural Resource Damage Assessment has not yet been released, preliminary status updates provide some insight into the damage caused by the spill. Approximately 1,750 km of coastline were oiled, 220 of which were heavily oiled. As of April 2012, field teams had collected 8,567 live and dead birds, of which 1,423 were rehabilitated and released. They collected 536 live sea turtles, of which 469 were later released, and 613 dead sea turtles. An Unusual Mortality Event for cetaceans in the northern Gulf of Mexico was declared prior to the spill, in February 2010, and is still in effect.

Kulluk — On December 27, 2012, the Kulluk, Shell’s conical drilling unit, was being towed from Dutch Harbor after drilling in the Beaufort Sea to Seattle for maintenance when its tow connection to the Aiviq separated. Although an emergency tow line was established between the Kulluk and both the Aiviq and the Nanuq, the Kulluk’s connections with both ships ultimately separated again on December 30. On December 31, the Kulluk grounded off of Sitkalidak Island, Alaska, due to strong winds and rough seas. On January 2, 2013, a salvage assessment team noted that the Kulluk had sustained some damage, but that it was stable and no sheen was visible. At the time that it grounded, the Kulluk was carrying approximately 139,000 gallons of ultra-low-sulfur diesel in addition

COMMITTEE PROCESS

The National Research Council’s Committee on Responding to Oil Spills in Arctic Marine Environments was formed to address the Statement of Task in Box 1.2. The committee’s work was sponsored by eight agencies and organizations—the American Petroleum Institute, the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, BSEE, BOEM, the U.S. Coast Guard, the Marine Mammal Commission, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Oil Spill Recovery Institute. The committee represents a broad spectrum of knowledge and expertise related to oil spill response or the Arctic environment; committee membership is listed in Appendix A. Rosters for each of the National Research Council boards involved in the study are in Appendix B.

Committee meetings were scheduled in different locations to afford opportunities for participa-

to the 12,000 gallons of combined lube oil and hydraulic fluid needed for onboard equipment. Approximately 316 gallons of ultra-low-sulfur diesel fuel were released from the Kulluk’s lifeboats. On January 6, the Kulluk was refloated and moved to nearby Kiliuda Bay. Multiple salmon-bearing streams are located near the grounding site and Kiliuda Bay. Sitkalidak Island and Kiliuda Bay are within the area designated as critical habitat for Steller sea lion and southwest sea otter populations. These areas also provide habitat for waterfowl and shorebirds (including the Endangered Species Act-listed Steller’s eider), as well as harbor seals. Fin and humpback whales may also have been in Kiliuda Bay. However, no specific impacts to wildlife have been reported.

Selendang Ayu — On November 28, 2004, the Malaysian-registered bulk freighter Selendang Ayu departed Seattle, Washington, and began its trip to Xiamen, China. The vessel was loaded with soybeans and 1,000 metric tons of fuel. On December 6, in the Bering Sea, the vessel experienced engine failure. Despite attempts to fix the engine, it would not restart. Efforts over the next 2 days to tow the vessel were compromised and ultimately failed, due largely to weather. After drifting significantly, the Seledang Ayu ran aground near Unalaska Island, spilling 336,000 gallons of fuel and diesel fuel. Resources that were reportedly damaged from the spill include birds, fish, and vegetation. Following the incident, shoreline cleanup assessment teams identified nearly 115 km worth of shoreline segments that would require additional treatment. Some of the most heavily oiled areas were beaches located at the mouths of streams, which serve as habitat for anadromous fish. The carcasses of approximately 1,700 birds were either recovered or documented.

SOURCES: Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council (http://www.evostc.state.ak.us/); NOAA Office of Response and Restoration (http://response.restoration.noaa.gov/exxonvaldez); NOAA Gulf Spill Restoration (2012); Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (http://dec.alaska.gov/spar/perp/response/sum_fy13/121227201/jic/TimelineAndMap.pdf; http://dec.alaska.gov/spar/perp/response/sum_fy13/121227201/121227201_sr_09.pdf; http://dec.alaska.gov/spar/perp/response/sum_fy13/121227201/121227201_sr_13.pdf); Kulluk Tow Incident website (https://www.piersystem.com/go/doc/5507/1674235/#.UoOk8-LO2M0); National Transportation Safety Board marine accident brief (http://www.ntsb.gov/doclib/reports/2006/MAB0601.pdf); U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (http://www.fws.gov/alaska/fisheries/contaminants/spill/sa_injury.htm).

tion by committee members, stakeholders, interested parties, and the public. Prior to formal committee meetings, committee and staff members attended workshops in Kotzebue and Barrow in order to interact with local stakeholders and decision makers. Committee activities included information gathering through presentations and discussion, small group meetings, and writing sessions. The committee drew on the large volume of recent reports that deal with many aspects of the Arctic, especially those related to ecosystem change, developments in shipping and energy exploration, and policy. They also examined experiences and lessons learned from several oil spills and marine transportation accidents. The committee notes that the report sponsors asked for a specific focus on U.S. Arctic waters of the Bering Strait, Chukchi Sea, and Beaufort Sea. This region is the main focus of the following chapters, with only limited emphasis on U.S. Arctic waters in the Bering Sea and points farther south for context. There is also limited focus on international Arctic waters outside U.S. jurisdiction, except as it pertains to oil that could potentially spread into U.S. waters.

The National Research Council (NRC) will assess the current state of science and engineering regarding oil spill response and environmental assessment in the Arctic region (with a specific focus on the Bering Strait and north), with emphasis on potential impacts in U.S. waters. As part of its report, the NRC-appointed committee will assess existing decision tools and approaches that utilize a variety of spill response technologies under the types of conditions and spill scenarios encountered at high latitudes. The report will also review new and ongoing research activities (in both the public and private sectors), identify opportunities and constraints for advancing oil spill research, describe promising new concepts and technologies for improving the response, including containment (surface and subsurface) approaches to reduce spill volume and/or spatial extent, and recommend strategies to advance research and address information gaps. The committee will also assess the types of baselines needed in the near term for monitoring the impacts of an oil spill and for developing plans for recovery and restoration following an oil spill in U.S or international waters where a spill could potentially impact U.S. natural resources. For assessing the state of the science, the committee will address the following topics:

(1) Scenarios. Identify areas in U.S. or adjacent waters where current or potential activities could lead to an oil spill in the marine environment (marine transportation routes, cruise ships, fishing, pipeline locations, fuel storage facilities, oil and gas exploration and production). The scenarios would include descriptions of oil type (including biofuels and diesel fuel) and possible volume and trajectories of spills, season, and geographic location, including proximity to local communities and highly valued fish, bird, and marine mammal habitats.

(2) Preparedness.

- Describe the anticipated operating conditions, such as ice conditions, currents, prevailing winds, weather, amount of daylight, sea state, and distance/accessibility from responders and resources. This will include an evaluation of the state of hydrographic and charting data for higher risk areas.

- Assess infrastructure (including communication networks), manpower, and training necessary to operate in these conditions.

- Identify avenues for participation of and communication with indigenous communities and regional governmental (e.g., Alaska State) entities during planning and response.

REPORT ORGANIZATION

While the following chapters are roughly divided along the charges within the Statement of Task, there are many areas where the charges are woven together or split apart. Chapter 2 discusses the environmental conditions, baseline needs, and marine activities in the U.S. Arctic. This chapter mainly addresses task 4 on strategies for establishing the types of baseline information needed before a spill, but also addresses part of task 2 regarding anticipated operating conditions. Chapter 3 examines current and ongoing oil spill response research, as required in task 3, to evaluate existing

- Build on existing agreements and identify gaps for international cooperation in establishing locations for incident command management, staffing, and supplying oil spill response infrastructure, recognizing the international interests in navigation and resource exploitation in Arctic environments.

(3) Response and Cleanup. Evaluate the effectiveness and limitations of current methodologies used in response to a spill in Arctic conditions.

- Assess utility of existing and promising new technologies to detect, map, track, and project trajectories of spills under the anticipated operating conditions (e.g., ice conditions, visibility).

- Evaluate the effectiveness of oil spill response technologies under the following criteria:

- Operation under various conditions and time frames (volatile fractions, wind, sea state, temperature, degree of emulsion, oil type and viscosity);

- Spatial and temporal dimensions of the spill and the response;

- Transportation of equipment to remote areas;

- Natural oil degradation rates; and

- Ancillary effects of response operations on the indigenous communities, environment, and marine species.

- Assess the potential response strategies for the separation and recovery of oil from marine waters, on or associated with ice, sediments, and the shore zone, including an assessment of their contributions toward habitat recovery. This assessment will include discussion of constraints in the handling, storing, and disposing of recovered oil in situ or in remote locations, the volume of material to be treated, selection of methodologies for incineration or recycling onboard ship or in a remote location, and the further disposal or transport of the recovered product. The assessment will also include discussion of fate and effects of unrecovered oil left to biodegrade and weather in Arctic environments.

- Assess the capabilities and constraints for minimizing impacts and enhancing recovery of wildlife through deterrence and rehabilitation.

(4) Strategies for Establishing Environmental Baselines for Spill Response Decisions. Characterize the types of baseline information needed in the event of an oil spill. Evaluate existing pre-spill strategies for resource protection and identify additional protection options for resources at risk. Identify sampling and monitoring priorities for establishing baseline conditions and evaluating impacts of a potential spill.

and new technologies available to respond to an oil spill and their effectiveness. Chapter 4 addresses operations, logistics, and coordination in response to an Arctic oil spill, which relates to task 2 on operating conditions and infrastructure, as well as the opportunities to build on existing agreements and partnerships. Chapter 5 deals with evaluation of response technologies and strategies, an element of task 3. To address task 1, the committee introduces some representative scenarios as part of the risk framework discussion in Chapter 3, with further scenario development and discussion in Chapters 4 and 5.