In the course of addressing specific aspects of an academic career, all of the speakers contributed to a description of the overall structure of an academic research career. Before drilling down into the details, it is useful to sketch this general framework and see the big picture.

STRUCTURE OF THE ACADEMIC RESEARCH CAREER

Implicit in all the workshop discussions was a shared understanding of how a traditional academic career progresses. Basic to this system is tenure, a promise of lifetime employment as a faculty member at a particular institution. Once earned, tenure is very rarely lost, and then only for severe misbehavior by the individual or extreme financial difficulty of the institution. Attaining tenure makes an individual a participant in certain aspects of the institution’s governance, including decisions about hiring and granting tenure to others.

Only particular job slots that the institution designates as belonging to the so-called tenure track carry the possibility of providing tenure. Positions not on the tenure track may involve similar duties, such as teaching, research, advising students, and serving on certain committees, but they do not offer a promise of permanence or provide the status within the academic community that tenure does. In former times, tenure constituted the institution’s promise to provide all or at least part of the faculty member’s salary until he or she elected to leave or reached retirement age. In many institutions today, however, tenure often provides only a platform from which faculty members can engage in the competition for funding to support their work and provide their own salaries. The extent of dependence on outside support differs considerably across disciplines.

To have a chance of winning tenure, a scholar must first secure a position that is explicitly designated as part of the tenure track. Positions in this sequence carry one of three ranks: assistant professor, which is the lowest;

associate professor; and full professor, which is the highest. Tenure is not automatic and successful candidates must win the approval of both departmental colleagues and the higher administration of their institution. Assistant professors serve a probationary period that can last up to 7, or sometimes 10, years. During this time, the candidate strives to amass a record of research publications and successful grant applications—and, to a much lesser extent, of teaching and service to department and university—that the institution deems acceptable. Unsuccessful candidates must leave the university and seek employment elsewhere. The years preceding tenure therefore constitute a make-or-break period of great tension, long hours, and hard work.

Appointment to a tenure-track assistant professorship certifies the individual as an independent investigator who has the institution’s backing in the competition for research grants.2 In fields that require laboratories, equipment, and workers to produce research results, universities provide new assistant professors start-up money to establish their laboratories. In return, the new assistant professor is expected to start providing money to support the laboratory within a few years by winning competitive grants, usually from the federal government.

The decision about whether to grant tenure comes after a predetermined number of years, with a symbolic “tenure clock” marking the time to one of the most fateful moments in the assistant professor’s life. Attaining tenure generally coincides with promotion to the rank of associate professor, which brings higher pay and greater status and recognition. Above that, only the rank of full professor remains, although within that rank, many universities award additional recognition in the form of distinguished, University, or named professorships. Reaching that highest rank places a scholar among the senior faculty members of the institution and, for many, indicates attainment of a successful career. This final promotion decision is again made by the candidate’s departmental colleagues and the higher administration, and again, the decision overwhelmingly depends on their estimation of the quantity and quality of the candidate’s research. The requirement to do top-tier research is paramount at doctorate-granting, research-intensive universities.

Attaining a full professorship has no set time limit, and some faculty members never reach that rank and remain associate professors throughout their careers. At retirement, both full and associate professors may receive emeritus status, a largely honorific title that indicates a continuing connection to the department and may, depending on the university’s resources, include such perquisites as use of an office and lab, computer accounts, administrative support, and the like.

Given the stringent requirements for advancement at middle- and upper-tier institutions, competition marks most stages of a topflight academic career—competition to be hired into a tenure-track position, to win funding, to make

_____________________

2 Many universities also have research faculty positions that might enable independent research but that typically do not provide access to tenure and are considered less prestigious.

discoveries that will make one’s name, to be first to publish them. Although this competition for top people occurs in all fields, the need to attract external research funding is particularly important in the sciences and engineering. Particularly successful competitors—those who consistently receive substantial research support and achieve publications in prestigious journals and build eminent reputations within their fields—can win prestigious and lucrative honors and receive appealing offers to move to other institutions, bringing their productive labs and attendant grants with them to their new academic homes. Leading researchers in a field may make several such moves.

In the early 1970s, as a graduate student looking forward to her future, Shirley Malcom, head of the Directorate for Education and Human Resources Programs, American Association for the Advancement of Science, saw “an expected arc to my life and my career,” she told the workshop in its opening session. She and her fellow Ph.D. candidates, she said, were led to believe that a new Ph.D.’s career would follow the same course as their professors’. “When I finished my Ph.D.,” Malcom recalled thinking, “I would enter a tenure-track position…I would gain research independence [and] get an early first grant,…would get tenure,…would be promoted” and would remain a member of a university faculty until she reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. Deviating from the “pathway [that] was set out” by taking a position outside of academe, she said, constituted “choosing an alternative career.”

Malcom, an African American woman, recalls believing this even though the research university professoriate she hoped to join consisted of people “quite different” from herself: overwhelmingly male and white, with women constituting only 2 percent of the full professorships in science and engineering and minority group members hardly visible in those ranks at all.

From the apparent predictability and stability that students saw four decades ago, “we have moved…to a time of flux and uncertainty in higher education,” Malcom continued. Today’s graduate school students and aspiring scientists, who are the “academic progeny” of Malcom’s generation, need a different set of expectations for the very different world of today and tomorrow, she said. This generation “will likely not have [their] mentor’s career” and should not “even expect it, because things really have changed a lot.”

Change has been so great, she continued, that for today’s graduate students and young Ph.D.s, the traditional progression from graduate student to tenured professorship is now, statistically at least, the “alternative career.” The number of tenure-track positions has increased very little in recent decades, except in engineering, but the number of Ph.D.s awarded in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields has increased very rapidly, far outstripping the availability of tenure-track positions. Edie Goldenberg, professor of political science and public policy at the University of Michigan, and Henry Sauermann, assistant professor of strategic management at the Ernest

Scheller, Jr., College of Business at Georgia Tech, observed that, as the academic job market has become increasingly overcrowded new Ph.D.s in many fields who hope for academic careers now must spend up to 5 or more years as postdoctoral researchers (known as postdocs), gaining training needed to advance their careers. Only then can they even attempt to look for a tenuretrack position, added Mary Ann Mason, co-director of the Center for Economics & Family Security at the University of California-Berkeley School of Law, and the odds of success have steadily declined.

The minority who manage to secure a foothold on the tenure track are in their late thirties to early forties, on average, before they win their first independent grant, which establishes a scientist as an independent principal investigator (PI), Malcom noted. The route to a faculty career has become so protracted, she said, that since 2002 the percentage of PIs older than 61 has exceeded the percentage under age 36, even though the early years of scientific careers are often thought to be the most creative.

A second great change has been the composition of both the graduate student and postdoc populations and the professoriate, as women have entered graduate school and the academic profession in large numbers. Robert Hauser, the executive director of the Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education at the National Research Council and the former director of the Center for Demography of Health and Aging at the University of Wisconsin, who joined Malcom in setting the stage for the issues the workshop would consider, noted that the percentage of women earning STEM doctorates has risen substantially in all fields, but especially in the life sciences. In 2009, women earned 55.6 percent of Ph.D.s in the life sciences, and about 30 percent in the physical sciences, mathematics, and engineering 3

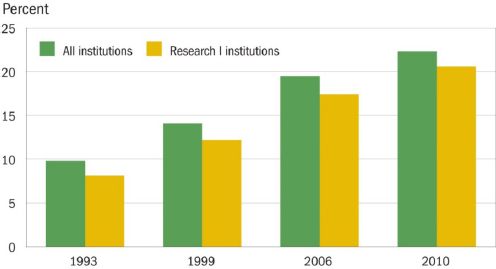

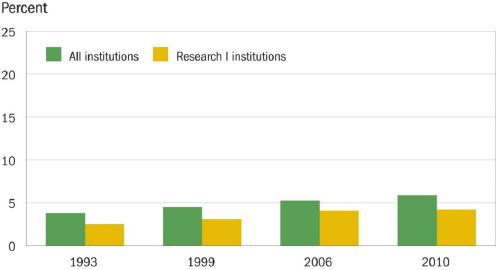

Women have also made striking gains on science faculties, Malcom noted. In 1993, they constituted 8 percent of the full professors in the sciences, engineering, and health fields at research universities and just under 10 percent in all institutions. By 2010, those figures stood at just over 20 percent and nearly 25 percent, respectively (see Figure 2-1). The percentage of full professors in those fields who were members of an underrepresented minority, however, remained below 5 percent at research universities and about 5 percent at all institutions in 2010 (see Figure 2-2).

Third, the economic robustness of research universities, and of the scientific, scholarly, and educational activities that they support, has noticeably deteriorated. As highlighted by the 2012 National Research Council report on research universities,4 major causes include “unstable federal funding,…an erosion of state funding for higher [education], a dismantling of the large corporate labs by business and industry, [and inadequate] management and [in]efficiency,” Malcom said.

_____________________

3Table 335 Doctorate Recipients From U.S. Universities: Summary Report 2008–09,

4 Research Universities and the Future of America: Ten Breakthrough Actions Vital to Our Nation’s Prosperity and Security. (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012).

Figure 2-1 Women as a percentage of full-time, full professors with science, engineering, and health doctorates, by institution of employment: 1993–2010.

SOURCE: Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2013; www.nsf.gov/statis.

Figure 2-2 Underrepresented minorities as a percentage of full-time, full professors with science, engineering, and health doctorates, by institution of employment: 1993–2010.

SOURCE: Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2013; www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/.

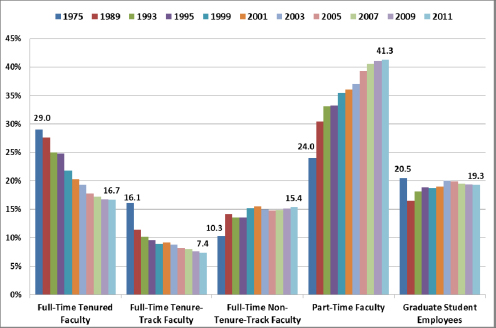

One response to these pressures has been a striking increase in the use of contingent or adjunct faculty, who cost less than tenure-track professors and do not require the start-up packages and lifelong job commitment that tenured faculty receive. The “adjunctification” of university faculties is “a huge change in the nature of academic employment,” Hauser said. Full-time tenured faculty at all U.S. postsecondary institutions declined from 29 to 16.7 percent of instructional staff between 1975 and 2011 and tenure-track faculty, from 16 to 7 percent. Meanwhile “huge increases occurred in full-time non-tenure-track faculty [from 10.3 to 15.4 percent] and especially in part-time faculty,” from 24 to 41 percent, he said (see Figure 2-3).5 “That is a big change in the character of the academic workforce over these years.”

Figure 2-3 Trends in instructional staff employment status, by percent of total instructional staff for all institutions, national totals: 1975–2011.

NOTES: Figures for 2011 are estimated. Figures from 2005 have been corrected from those published in 2012. Figures are for degree-granting institutions only, but the precise category of institutions included has changed over time. Graduate student employee figures for 1975 are from 1976. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, IPEDS Fall Staff Survey. Tabulation by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) Research Office, Washington, D.C. Released April 2013.

_____________________

5 Although this trend is more pronounced in non-research institutions, it is common at research universities as well.

Other important changes now affecting academic careers include the abolition, as of 1994, of mandatory retirement for tenured faculty; the rapid growth of 2-year colleges as a major source of undergraduate instruction; and the advent of online and blended instruction, which carries as yet unknown but potentially significant effects on existing academic institutions.

Together, all these changes have introduced major new issues to campus life. While Malcom’s professors mostly had wives at home to raise their children and run their households, today both female and male faculty members must balance the demands of academic careers and family life. Perhaps most crucially for career success, the current elongated training period and pretenure years overlap women’s prime years of fertility and both genders’ major time for family formation. Today’s faculty members—and their employers—must also negotiate the issues surrounding retirement, which has become discretionary rather than mandatory at a specified age.

The seemingly stable career arc that appeared to lie before aspiring academics during Malcom’s graduate school days has irrevocably shattered. The more complex paths that today’s and tomorrow’s academics must follow, and ways that institutions may help or hinder their journeys, are the topics of the remaining sessions.

This page intentionally left blank.