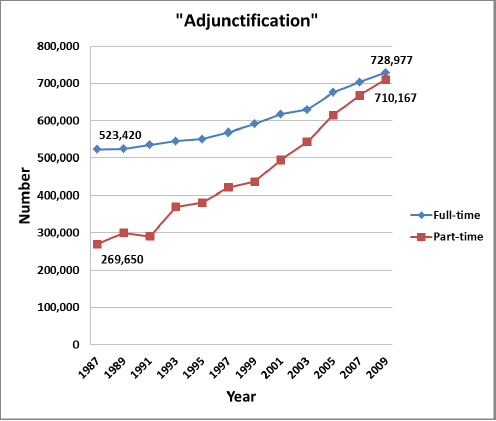

Many of the issues that aspiring academic scientists encounter in graduate school and postdoc days persist and even sharpen as they reach the tenure track. As was noted by many of the participants, some of the former graduate students and postdocs who do not succeed in making this jump of course seek careers in nonacademic fields. Substantial numbers remain in academe, however, as “non-track” or “off-track,” adjunct, contingent, or part-time faculty who are hired on a temporary basis to give either individual courses or full teaching loads. Consisting “disproportionately [of] women Ph.D.s with children,” this “cheap labor force” provides an increasing share of undergraduate instruction nationwide, Mason said. The ranks of the part-time faculty, Valerie Martin Conley, professor of counseling and higher education and co-director of the Center for Higher Education at Ohio University, noted, have grown much faster than those of full-time faculty (see Figure 4-1).

In “2009, we had gotten to a point where we had a one-to-one ratio of [fullto part-time] people who were employed as faculty, [doing] instruction, research, or service, at all postsecondary institutions in the U.S.,” Martin Conley said. “Most research data…[show] that there are now actually more people employed part-time than full-time in the category ‘faculty,’ “ she added. Many part-time instructors entirely lack health, retirement, and other benefits from the universities where they work. Full-time contingent faculty members may receive some or all of those benefits, but often less generous plans than tenured and tenure-track colleagues enjoy.

Those faculty members who have taken the crucial step that offers them the chance of attaining the security, permanence, and status provided by tenure now turn their focus toward winning that goal, an effort that can, depending on the institution, last 7 or even 10 years. Success demands great amounts of time and energy to amass a record of publications and successful grant applications, as

Figure 4-1 Number of full-time (tenured, tenure-track, and non-track positions) and part-time faculty: 1987–2009.

NOTE: For further detail, see Figure 2-3.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Higher Education General Information Survey (HEGIS), Employees in Institutions of Higher Education, 1970 and 1972, and "Staff Survey" 1976; Projections of Education Statistics to 2000; Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), "Fall Staff Survey" (IPEDS-S:87-99); IPEDS Winter 2001-02 through Winter 2011-12, Human Resources component, Fall Staff section; and U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Higher Education Staff Information Survey (EEO-6), 1977, 1981, and 1983., Table 290, (This table was prepared July 2012).

well as effective teaching and institutional service, to meet their particular department’s and university’s standard of productivity.

Because assistant professors are often in their mid-thirties or older, however, most are also coping with the conflicts and contradictions of pursuing demanding careers while fulfilling family responsibilities, often in a household with two working spouses or partners. “We discovered that more than 70 percent of both tenured and tenure-track faculty were partnered and more than 75 percent of those had working partners,” Joan Girgus said. Unlike the faculty

members of Shirley Malcom’s graduate school days, very few today can rely on a spouse at home to manage household and family matters. “Furthermore,” Girgus continued, “more than half our faculty—male and female—reported having ongoing care responsibility for children under the age [of] 18.”

As highly educated professionals, academics and aspiring academics also tend to marry other highly educated people; female scientists show a particular propensity to marry other scientists. This adds the extra complication that the spouses of many academics also have serious careers of their own, whether on campus or off, Girgus noted. Making the move to new universities, which is often needed to advance an academic career, also often requires moving to a new city or region. Accommodating the spouse’s career can thus pose a difficult and even insuperable challenge, both for universities seeking to hire new faculty and for faculty couples wishing to stay together while pursuing both professional interests. These days, two-city academic marriages are far from rare.

“The dual-career issue is a major problem,” said Carol Hoffman, associate provost and director of the Work/Life program at Columbia University, which happens to be in the nation’s largest metropolis. “It is easier in a city like New York than it is in some rural smaller communities.” In more bucolic Princeton, on the other hand, “dual-career issues have been and continue to be the most challenging, both for faculty members and for the university,” Girgus said. Finding acceptable solutions is “crucial for faculty being recruited from other universities.” Indeed, suggests Mary Ann Mason, the complications of pursuing an academic career while part of an academic couple may explain the “odd finding” that “single mothers actually do better than married mothers in terms of getting tenure,” because they are freer than women with spouses to make the moves that are best for their own careers.

In past generations, university nepotism rules often forbade spouses from working in the same department or even at the same institution, and women’s aspirations often took the back seat to their husbands’ careers, Malcom observed. More recently, however, as Girgus and Hoffman noted, universities’ attitudes have changed to match the reality of today’s many two-career households, and now institutions try to help find suitable positions for the spouses of faculty relocating to their campuses, either in their own or neighboring academic institutions or with other employers in the surrounding community.

As female assistant professors undertake the drive for tenure, however, a factor even more important than the quality and quantity of their research can determine their ultimate success: whether or not they have a baby soon after earning their Ph.D.. Between 1979 and 1995, only 53 percent of women on the tenure track with “early” offspring—defined as those born within 5 years of the mother’s Ph.D.—won tenure, said Mason, citing information from the Survey of

Doctoral Recipients. Men with early babies, on the other hand, attained tenure 77 percent of the time, and women with “late” babies—a first child born 5 or more years after the Ph.D.—did so 65 percent of the time. Also, married mothers were 35 percent less likely than married fathers to get onto the tenure track in the first place.

The pattern of long work hours—and extra-long hours for mothers—of course follows scientists onto the tenure track. Among faculty members at the University of California-Berkeley aged between 30 and 50, Mason said, mothers put in the longest work week—just over 100 hours—but spend fewer hours on professional tasks—51.2—than any category of colleague. Faculty fathers come second in working time—just under 90 hours a week in total—but spend 4.2 more hours on professional work than mothers. They also spend 15.2 fewer hours a week on caregiving and 2.7 fewer on housework.

Non-parents of both genders meanwhile keep quite similar, and less stringent, schedules: nearly 80 hours of total work a week, 60 of them devoted to professional work, about 10 to housework, and about 8 to caregiving. “Some things are changing, but…some things aren’t changing very much,” Mason said. “The women are still bearing the brunt of the housework for sure.” As these patterns show, “Research tends to be the piece that you can, in fact, shorten if you run out of time because of family life,” Girgus observed. “That can have serious consequences” for one’s career.

Given the terrible press of time on academic mothers, “One of our science department’s chairs said to me [that] he tells women to wait until tenure before they start having a family,” said Cathy Trower, research director of the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at the Harvard School of Education. But, she added, “if [women] wait to have a baby until they get tenure, if it is 9 years or 10 years on the tenure track, it probably will be too late.”

The intense pressure to achieve tenure is also a probable reason that tenuretrack women have fewer children than comparable men. In 2003, for example, Mason said, 73 percent of female assistant professors at the University of California-Berkeley were childless, as opposed to 61 percent of the males. Similar percentages of women and men had a single child—15 percent and 17 percent, respectively—but men were about twice as likely to have larger families—12 percent with two children and 10 percent with three or more, as opposed to 7 percent of women with two children and 5 percent with three or more.

Recognizing that the quest for tenure and the desire to have children are sometimes in conflict and wanting to increase the diversity of their faculties by hiring and retaining qualified women, many universities have adopted programs to help faculty members balance their career and family responsibilities. These often include the ability to stop the tenure clock for a set period, assistance with child care, and other services (see Box 4-1). At Princeton, which has an extensive range of professional and family policies to aid assistant professors,

and which endeavors to “do all that it can to help assistant professors get tenure,” Girgus said, “men and women assistant professors at Princeton receive tenure at the same rate and have for at least 30 years.” But, as John Tully, Sterling Professor of Chemistry and a professor of physics and applied physics at Yale University, noted, “Many of the possibilities that we have at elite institutions might not be true for most of the academic faculty in academic careers.”

Box 4-1

Examples of Family Support Policies

Princeton University

- Maternity leave

- Automatic 1-year extension of the tenure clock for each child

- Work-load relief for the primary caretaker

- Backup care program

- Dependent care travel fund

- Employee Child Care Assistance Program

- Expanding on-campus child care

- Employee Assistance Provider Work/Life Program

- Partner placement assistance

- Tuition grants for college-aged children

Columbia University

- Part-time Career Appointment

- Maternity Disability

- Child Care Leave

- Parental Workload Relief

- Tenure Clock Stoppage (for parental reasons)

- Assistance finding housing, schools, and other needed services, including partner placement

Family-friendly policies also appear to have taken some of the pressure off young faculty at the University of California-Berkeley as well and to have encouraged more women to have children before reaching tenure, Mason suggested. In 2009, the birth of new babies was up two-thirds over 2003 for female assistant professors and up 20 percent for males. Faculty fathers, however, still had larger families.

More detailed information about the effects and utility of family policies, Hoffman told the workshop, comes from a study by Columbia University aimed at seeing both whether its family policies have accomplished their intended purpose and whether complaints that some people abuse the policies are valid. Looking at records from 1990 to 2008 for tenured and tenure-track faculty from across the university (except for the medical center), the study took note of individuals’ department, gender, age, dates when they made use of a policy, how many times they used the policies, and how their careers progressed. The study identified 167 faculty members who had availed themselves of one or more parental policies during those years, 42 of whom were tenured and the rest on the tenure track. Significantly, only 14 percent of users came from natural science departments and 4 percent from engineering, perhaps indicating the low numbers of women in those fields, Hoffman said. Social science departments accounted for 38 percent of the users; professional schools, 23 percent; arts and humanities, 21 percent.

The policy most popular among both tenure-track and tenured faculty is parental workload release, which removes teaching responsibilities for a set period. “Tenure-track women use the workload relief in similar numbers to men,” Hoffman said, noting that this represents “a way greater percentage of women,” because they constituted only 30 percent of the faculty overall. Among people with tenure, however, 31 men and 9 women used teaching relief, numbers “more proportionate” to the mix of genders in the overall faculty.

Men and women both made their first use of teaching relief on average in the middle of their fourth year after being hired. The 51 women who used it while on the tenure track at Columbia “ranged from 29.4 years old to 42.4 with an average of 36.6 for the tenure track, a pretty high age” for a first child, Hoffman said. The nine women past tenure making their first use were an average of 42 years old, and Hoffman observed that “the chance of maintaining fertility at that age is actually quite slim.”

Thirty-two faculty members, 20 of them before tenure, made use of two periods of teaching relief. The numbers for the two genders were “almost the same,” with men forming a small majority. Hoffman believes that this provides further corroboration for “work at Berkeley and other places [showing] that men are having more children than women during their academic career.” More evidence, Hoffman added, appears to come from the 69 faculty parents adding new children to Columbia’s health plan during 2007 and 2008, 54 of whom were men and 15 of whom were women. Only 2 of the mothers had attained tenure and 13 were still on the tenure track. These figures do not provide definite proof, however, Hoffman noted, because some of the parents may have availed themselves of health plans provided by a spouse’s job.

Did teaching relief affect tenure outcomes? The study had no control group, so no conclusion was possible, Hoffman noted. Despite this, “we were pleased to see that a lot of folks, in fact, did proceed with tenure.” When the study closed in 2008, however, 49 percent of the users were still on tenure track

at Columbia or other universities, and another 43 percent have attained tenure, 25 percent at Columbia. But the study also corroborated another conclusion of “the research from Berkeley, that more women than men left their tenure track and tenured positions…and went into research positions,…administrative positions,…adjunct faculty part-time, faculty lecturer positions, but no longer were [on] tenure track or tenured.”

Over time, the study revealed, the use of teaching relief has become “normalized” at Columbia; in 2008 alone, 28 individuals used it. Though the earliest users of family policies were “a handful of brave women in the seventies and eighties, and early nineties,” Hoffman said, it is now “just sort of understood that if you have a child, you use teaching relief.”

But even if family policies help women achieve tenure, the effort “must be [taking] a greater toll on their own selves and well-being because they have [fewer] hours for themselves overall,” because of the heavy load of child care and household responsibilities that so many bear. “It doesn’t look like women aren’t getting tenure, but,” Hoffman asked, “what is it that it is taking out of them?”

“In the United States,…we don’t have [national] maternity or parental leave policies, and we don’t have affordable early child care starting at the earliest stage,” Hoffman continued. “Most developed countries have either lengthy initial year or two of time off when you have a child, or have free and early child care. For scientists, full-time long-day full-year child care is absolutely imperative, because your labs run like that. You don’t get summers off…[Child care] is a national issue. Universities can’t solve it alone.”

The demands involved in caring for children may, in fact, account for what Girgus called “one of the very few differences between men and women faculty that we have at Princeton”—an extremely wealthy institution with superior career and family supports for faculty—“women spend longer as associate professors than men do” before winning advancement to full professor. One possible reason, she suggested, may be that “they are more reluctant to stand for promotion.” But another plausible explanation could be that “a lot of women faculty, a fair percentage, do wait until they have tenure before they have children,” she said.

Apart from that, though, associate professor status generally constitutes “a continuation,” Girgus said. Professors continue with their research and other duties. And it is now clear that an individual will likely be at the institution until retirement, unless lured away by a more attractive offer from elsewhere. For this reason, “we believe it is crucial that faculty begin seriously planning for retirement at this point,” although, she said, many decline to do so.

At the same time, promotion to associate professor is also the point when invitations to move to other institutions begin to arrive in earnest. “Once they get tenure, that is when they get heavily recruited. We have a big spike up in

outside offers around age 40, 45,” said Marc Goulden, the director of data initiatives in the Office for Faculty Equity & Welfare, University of California-Berkeley, who conducted a study of the University of California’s Voluntary Early Retirement Incentive Program. When this happens, Girgus notes, “dual-career issues get, if anything, more challenging.”

For those who remain at their original institution, however, “a rule of thumb is roughly 6 years on the tenure track, and then another 6 at associate before standing for full professorship,” Trower says. “However, research shows that many faculty remain at the rank of associate either because they never apply for full, or because they do and they are denied, and they stay.”

Research also shows that the longer people remain in associate status, the less satisfaction they feel about their working conditions and workplace, according to Trower, who reported on a study from the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education (COACHE) of 1,263 tenured associate professors in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields at a range of universities.7 The findings indicated that “people are pretty happy right after they get tenure,” she said. “Then, as they go through at associate, …at 7 to 12 years in”—at the point, in other words, where promotion to full professor may be expected—“there is a lot less satisfaction with the workplace.” Across the arc of a career, she said, “faculty job satisfaction follows a U. It starts high and it drops, drops, drops, drops in this trough. Then, it picks up again toward the end of one’s career.”

During the associate professorship years, she continued, faculty members often also begin to receive requests to take on serious service and leadership roles, such as chairing an important committee or the department. Such duties, while significant to the institution, take time from research and do not add to the person’s scientific reputation or grant support. Women in particular often report feeling that they must bear an inequitable share of the load and sense a “certain cultural taxation on women in the academy to do committee [or other] service,” she said. Research shows that men “will say no to leading the department until they get to full. Many women, [on the other hand], are tapped to be a director or a department chair.”

A “counterintuitive but interesting finding,” given all the research about the stress of academic motherhood, is that childless women associate professors express less satisfaction than those who are mothers. Possibly, Trower suggested, there might “actually be a pendulum shift, with all the focus now on people with kids,” leaving those who are not parents feeling overlooked. Or perhaps, having given up family for career, they feel disappointment in the outcome.

Then, finally, those who reach the top rank and find themselves “professor at last,” enter the “time to give back,” Girgus said. At Princeton, “we really

_____________________

7 More information can be found on the COACHE homepage, available at: http://isites.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=coache&pageid=icb.page307142

begin to jump on our full professors… . The minute you become a full professor, you are departmental representative or you are the director of graduate studies or you are chair of the department. There is a long list because we have a lot of faculty governance and a small faculty.” Beyond that, for academics who have attained eminence in their research fields, invitations to move continue to arrive. “We find dual-career issues here are absolutely crucial, both for recruitment and retention. Bringing people in from other universities or persuading them to stay at Princeton, it is the central piece of what we do in recruitment and retention, the central difficult piece, I should say.”

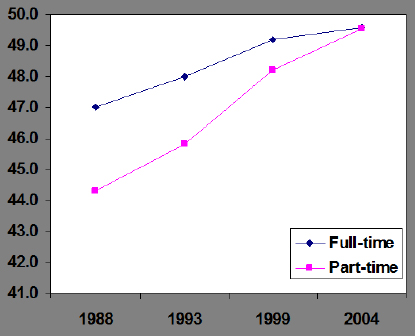

The issues of the later career underline another striking trend in higher education, what Martin Conley called the overall “graying” of the faculty. “Both full-time and part-time faculty are aging, as is the population,” she said. Between 1988 and 2004, “the average age of part-time faculty has increased from 44 to 50 years” and of full-time faculty from 47 to 50 years, according to the National Study of Postsecondary Faculty, she said (see Figure 4-2). In 1987, the percentage of full-time instructional faculty under the age of 40 slightly exceeded that of full-time faculty over 55, at 25.2 and 24.2 percent, respectively. By 2003, the older cohort was almost twice the size of the younger, at 34.9 percent as opposed to 19.2, respectively.

Figure 4-2 Average age of instructional faculty and staff by employment status at 4-year institutions for selected years: 1988, 1993, 1999, and 2004.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Study of Postsecondary Faculty (NSOPF).

One reason may be that people “are living longer, healthier lives” and probably fewer are dying young. But another is that, starting in the 1990s, faculty have been working longer. Between fall 1992 and 1998—with the end of mandatory retirement coming in 1994— the percentage of departures by fulltime faculty because of retirement declined, giving “one of our first clues that faculty were beginning to delay retirement,” Martin Conley said.

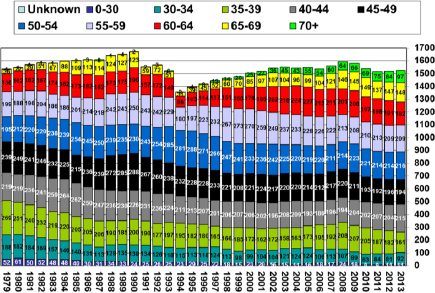

The age structure of the faculty at UC Berkeley, for example, shows an unmistakable trend toward growth among the oldest cohorts, according to data that Goulden supplied (see Figure 4-3). In 1979, faculty members under 34 years of age numbered 140 and those over 60, only 173. In 2013, the 97 faculty members over 70 outnumbered the 92 between 30 and 34, with only 11 aged below 30, as opposed to 52 in that youngest age bracket in 1979. Today, the 342 faculty members between 60 and 69 substantially outnumber the 253 between 30 and 39.

As faculty move into the later years of their careers, “retirement planning…moves to the forefront” in preparation for what Janette Brown, executive director of both the Emeriti Center at the University of Southern California (USC) and the Association of Retirement Organizations in Higher Education (AROHE), calls “the new life stage, which is roughly between the ages of 60 and 85.”

Figure 4-3 UC-Berkeley faculty headcount by age: academic years 1979-80—2013-14.

NOTE: Data for academic year 2013-14 is preliminary.

SOURCE: UCB Faculty Personnel Records, AY 1979-80—2013-14. Prepared by Goulden, September 2013; updated October 2013.