1

Supplementing the Balance-of-Payments Framework

Data on U.S. international transactions are currently grouped into three major categories: merchandise trade, international services transactions, and capital flows. Merchandise trade statistics, which cover U.S. imports and exports of goods, are assembled by the Bureau of the Census of the U.S. Department of Commerce on the basis of information contained in import and export documents. Those documents are collected primarily by the Customs Service of the U.S. Department of the Treasury as goods enter and leave the United States. Merchandise trade data are tabulated in detailed commodity categories and geographical breakdowns and are published monthly by the Census Bureau.

Data on U.S. international services transactions cover travel, transportation, and other services (royalties and fees; reinsurance and direct insurance; construction, engineering, architectural, and mining; and business, financial, medical, and educational services). Most of the data presently available on U.S. international services transactions are collected and compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) of the Department of Commerce on the basis of periodic surveys of establishments engaged in those services. U.S. international services transactions are published by BEA in broad categories and include limited country breakdowns on a quarterly basis.

Data on capital flows cover transactions on direct investment and portfolio investment, as well as on incomes and earnings gen-

erated from them. BEA collects information on both U.S. direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in the United States on the basis of periodic surveys of U.S. firms investing abroad and U.S. affiliates of foreign corporations in the United States. BEA publishes quarterly estimates of these activities.

The Department of the Treasury, using the Federal Reserve banks as agents, collects information on portfolio investment. Treasury International Capital (TIC) forms capture sales and purchases of long-term securities and amounts of outstanding claims and liabilities reported by banks and nonbanking concerns. Banks, financial institutions, brokers, dealers, corporations, and other entities in the United States that engage in portfolio transactions are required to file TIC forms. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York consolidates the data and makes them available to the Treasury Department, which publishes the data on a quarterly basis.

BEA compiles data on incomes and earnings on direct investment from its surveys of direct investment. It also estimates incomes and earnings on portfolio investment, using its calculations of selected rates of return and information on portfolio investment provided by the Treasury Department.

EXISTING STATISTICAL FRAMEWORK

These enormous quantities of data are compiled largely under the balance-of-payments framework. Underlying these compilations of data on U.S. international transactions are the concepts of residents and nonresidents and the separation of domestic and international economic activities. International transactions are defined to involve the transfer of ownership of goods, services, and capital flows between U.S. and foreign residents, with national boundaries establishing the distinction between residents and nonresidents. Under this framework, U.S. residents are persons residing and pursuing economic interests in the United States, and nonresidents are those residing and pursuing economic interests outside the United States. (Exceptions include members of the U.S. armed forces serving abroad, who are considered U.S. residents). The term “residents” is broadly defined to include individuals, business enterprises, and governments and international organizations.

These concepts are used because one common purpose of these statistics compiled by Census, BEA, and Treasury is to provide data for the nation's balance-of-payments accounts. The accounts represent a summary statistical statement during a given period of trans-

actions in goods, services, and capital flows between U.S. residents and those of the rest of the world. Components of the balance-of-payments accounts, in turn, are incorporated into the national income and products accounts (NIPA), which measure the production, distribution, and use of output in the United States by four economic groups: persons, businesses, government, and “the rest of the world.” BEA estimates both the U.S. balance-of-payments accounts and the NIPA on a quarterly basis. (For a detailed description of the concepts, data sources, and estimation procedures used in the balance of payments, see Bureau of Economic Analysis, 1990c.)

A country's economic transactions with the rest of the world are believed to be a function of fundamental economic conditions—such as relative levels of domestic and foreign prices, incomes, exchange rates, interest rates, and savings rates, and rates of economic growth between the country and the rest of the world. The balance-of-payments framework is valuable, therefore, for understanding changes in the nation' s general price level, and domestic output and employment. (The extensive use of the dollar abroad, however, has reduced the direct link between the U.S. balance of payments and the exchange rates of the dollar.)

The balance-of-payments framework was developed when the world economy was much less integrated. It reflects the economic conditions at that time, when sales and purchases by multinationals and their affiliates were much less significant relative to cross-border transactions than they are now. Under this framework, the scope of statistics on international transactions was developed primarily to cover cross-border movement of goods and selected services, the income earned on U.S. investments abroad and foreign investments in the United States, and the volume of capital flows. The balance-of-payments framework is not intended to account for sales of goods and services by affiliates or to distinguish intracompany trade from trade between unrelated parties. Yet key features of the internationalized economy are the significance of foreign direct investment and the close relationship between this investment and trade. As Julius (1990) has stressed, trade and foreign direct investment are twins in the sense that both enable firms in one country to reach markets for outputs or sources for inputs in other countries. Firms have found that they can exploit their own technological and managerial knowledge most profitably by establishing production units in foreign countries rather than just exporting to (or importing from) foreign markets or by permitting foreign firms to use their specialized knowledge for royalties and fees.

BEA estimated U.S. direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in the United States in 1989 at $536 billion and $458 billion, respectively, on a current-cost basis (see Landefeld and Lawson, 1991); on a market-value basis, the estimates are $804 billion and $544 billion, respectively. (Earnings on U.S. direct investment abroad and on foreign direct investment in the United States in 1987, which are recorded in the balance-of-payments accounts, were $55 billion and $10 billion, respectively.) The sales of goods and services by these foreign affiliates of U.S. firms and U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in 1987 were $815 billion and $731 billion, respectively. These transactions contrast with U.S. goods and services exported and imported in that year of $336 billion and $484 billion, respectively. The close connection between foreign direct investment and trade is further evidenced by other statistics. In 1987, goods and services exported by U.S. firms to their affiliates abroad accounted for 26 percent of total U.S. exports of goods and services, and goods and services shipped by foreign firms to their U.S. affiliates in the United States accounted for 30 percent of U.S. imports.

The increase in foreign direct investment and its link to trade has created a new set of policy issues among nations that did not exist when direct investment and intracompany trade were less important (see Cooper [1968:Chap. 4] for an early discussion of the new policy issues created by foreign direct investment). Concerns are often raised in host countries, for example, that affiliates of foreign firms give preference to suppliers from their home countries over local suppliers of intermediate goods and nonfactor services (such as insurance). Even though there is little evidence, it is also said that they neither export as much nor treat workers as well as domestically owned firms and that they stifle scientific research and development in host countries. There is also a fear that the cultural heritage of the country may be undermined. In contrast, concerns are often expressed in home countries that foreign direct investment abroad results in significant losses of jobs domestically and a decrease of tax revenues for the government. In addition, direct investors are concerned about being discriminated against in their economic activities in the host country.

Traditional international economic issues have also been modified by the increased importance of foreign direct investment. The competitiveness of a country's firms in world markets, for example, is no longer just a matter of their ability to export; it is also determined by their ability to sell through their affiliates abroad. New issues of macroeconomic policy, antitrust policy,

and tax evasion also arise with the mergers and acquisitions of U.S. firms by foreign companies, their establishment of domestic production facilities to circumvent import restrictions, and their transfer-pricing activities.

To analyze these issues, a framework that links direct investment and trade is needed: the existing balance-of-payments framework does not do since only earnings of foreign investment are included, and the trade balances do not differentiate the export and import activities of U.S. and foreign firms in the United States.

A SUPPLEMENTAL FRAMEWORK

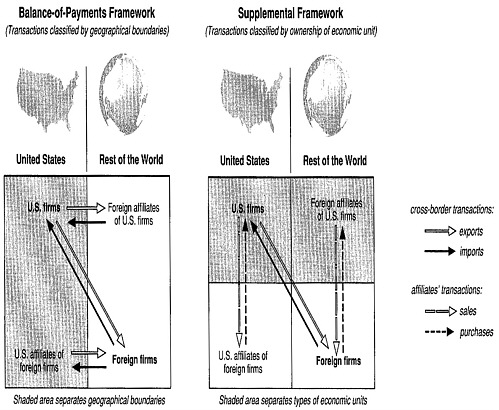

One way to develop a supplemental framework to analyze the new economic issues and the increasingly complex traditional ones is to integrate data on cross-border trade flows (as reported in the balance-of-payments accounts) with those on sales and purchases of goods and services of U.S. direct investors abroad and foreign direct investors in the United States, which are currently collected outside the balance-of-payments framework. Figure 1-1 shows the balance-of-payments framework and the panel's proposed framework.

The set of accounts being proposed measures the sales and purchases of goods and services by U.S.-owned firms (whether located in the United States or abroad), the U.S. government (but excluding military sales), and the households of U.S. residents to and from foreign-owned firms (whether located abroad or in the United States), foreign governments, and the households of foreign residents. (In estimating the set of accounts, no attempt is made to distinguish either between households of U.S. citizens and foreigners residing abroad or between households of U.S. and foreigners residing in the United States.) Since sales of goods and services are mainly undertaken by firms, for simplicity, the following description ignores sales by governments and households: see Appendix A for a complete description of the selling and buying activities between U.S.-owned firms, the U.S. government, and U.S. households and foreign-owned firms, foreign governments, and foreign households. To show the essential difference between the proposed framework and the balance-of-payments framework, Figure 1-1 is further simplified by assuming that purchases, as well as sales, are undertaken entirely by firms.

Under the proposed framework, total sales of U.S.-owned firms to foreign firms, foreign governments, and foreign households (referred to hereafter as “foreigners”) are computed in three steps.

First, exports of U.S.-owned firms to their foreign affiliates abroad and exports of U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in the United States to foreigners are subtracted from the total U.S. export figure, since they represent within-firm transactions between U.S.-owned firms and between foreign-owned firms, respectively.1 The net figure represents cross-border sales of U.S.-owned firms to foreigners. Second, to this figure are added sales to foreigners by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms abroad. Third, sales by U.S.-owned firms to U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in the United States are added.2 The sum, combining the three sources of sales, represents the total sales of U.S.-owned firms to foreigners.

Purchases of U.S.-owned firms, the U.S. government, and U.S. households (referred to hereafter as “Americans”) from foreign-owned firms are computed in three comparable steps. First, from total U.S. imports are subtracted imports from foreign affiliates of U.S. firms abroad and imports by U.S. affiliates of foreign firms located in the United States. The net figure represents cross-border purchases by Americans from foreign-owned firms. Second, to this figure are added purchases by Americans from U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in the United States. Third, purchases by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms abroad from foreign-owned firms are added.3 The sum of all three sources of purchases represents total purchases by Americans from foreign-owned firms.4

Components of the proposed set of accounts can be rearranged to yield related concepts that are of interest to policy makers.

|

1 |

A foreign (U.S.) firm is one that is organized, operated, or incorporated abroad (in the United States). An affiliate is a business enterprise located in one country that is owned or controlled by a single person or firm of another country to the extent of 10 percent or more of its voting stock. An unaffiliated firm is one that neither owns nor is owned by other firms in the 10 percent voting-stock sense. |

|

2 |

The data needed to obtain the latter figure are unavailable; it is only possible to obtain sales by all firms located in the United States to U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in the United States. |

|

3 |

The data needed to obtain the latter figure are not available; it is only possible to obtain sales by unaffiliated firms abroad to foreign affiliates of U.S. firms. |

|

4 |

After we developed our broadened framework, we discovered the work of DeAnne Julius, who developed a somewhat similar set of accounts; see Julius (1990, 1991). An important difference between her set of accounts and the one discussed here is that she includes payments to direct productive factors, for example, wages and capital costs, in her estimates of purchases of U.S. affiliates of foreign firms within the United States and purchases of foreign affiliates of U.S. firms abroad. As Guy V.G. Stevens of the staff of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve points out in an internal memo (July 25, 1990), this methodology leads to the result that the Julius measure reduces to the sum of the trade balance, other services (net), and net direct investment income (exclusive of capital gains). These figures can be obtained directly from the balance of payments. |

The value added in the United States by U.S. affiliates of foreign firms (that is, the gross domestic product of U.S. affiliates of foreign companies) can be calculated from their sales and purchases data. Similarly, the value added abroad by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms can be calculated from the data on the sales and purchases of those firms. The percentage of the local content of sales of U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in the United States (that is, the sum of value added and purchases from local firms divided by total sales of U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in the United States, expressed in percentage terms) can also be calculated, as can the foreign-content percentage of sales by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms. Appendix A discusses in detail the various components of this supplemental framework and presents estimates of sales and purchases of goods and services by U.S. firms to and from foreign firms for 1987.

Table 1-1 summarizes the difference in U.S. international economic performance under the balance-of-payments framework and the supplemental framework and also presents value-added and local-content estimates. The balance-of-payments framework in 1987 shows a U.S. trade deficit of goods and services of $148 billion; the supplemental framework shows that the sales of goods and services by U.S.-owned firms (located either in the United

TABLE 1-1 A Comparison of U.S. International Economic Performance Under Two Frameworks, 1987 (in billions of dollars)

States or abroad) are only $64 billion less than purchases from foreign-owned firms (located either in the United States or abroad). The value added in the United States by U.S. affiliates of foreign firms was $152 billion in 1987; in contrast, the value added abroad by foreign affiliates of U.S. companies was $244 billion. The local-content percentage was also higher for these latter firms (89 percent) than for U.S. affiliates of foreign firms (81 percent).

It should be emphasized that the figures derived from the supplemental framework do not mean that the usual macroeconomic concerns about the U.S. balance-of-payments accounts should be discounted. However, the supplemental framework provides additional perspectives on the impact of both foreign direct investment and trade on the economic performance of the U.S. economy; it should be used to supplement the balance-of-payments accounts. For some purposes, especially analyses of contributions to national output and employment, the resident-based statistics are appropriate. For other purposes, however, statistics based on ownership will be more useful to policy makers.

USES FOR PUBLIC AND PRIVATE DECISIONS

The supplemental framework can lead to improved decision making in several specific policy areas. Consider the issue of market access, for example. Today, managers of international firms are interested not only in improving the opportunities for their exports to enter foreign markets, but also in ensuring that the foreign sales of goods and services produced by their affiliates abroad are free of discriminatory rules and regulations within foreign markets. In the ongoing Uruguay Round of negotiations under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the negotiators are seeking to liberalize trade-related investment issues (TRIMS) and sales of services. The issues are likely to become more important in future negotiations. The supplemental framework, in measuring sales from home and abroad by both U.S. firms and foreign firms, would enable policy makers to assess the extent of market access of U.S. and foreign firms in the United States and in foreign markets.5 (Of course, for bilateral negotiations, sales information by country would be needed.)

|

5 |

BEA recently has presented a set of accounts for nonfactor services that provides such a picture by presenting data on the delivery of services to foreign and U.S. markets through cross-border transactions and through sales by affiliates; see DiLullo and Whichard (1990). |

Another key aspect of market access concerns the extent to which the sales of U.S. affiliates of foreign firms increase total wages and other forms of income and employment in the United States, in contrast to simply increasing wages, profits, and employment in foreign countries where their parent firms are located. In other words, what is the value added or gross domestic product contribution of U.S. affiliates of foreign companies to the total gross domestic product of the United States?6 In addition, policy makers may want to know the extent to which these firms purchase intermediate goods and services from producers in the United States rather than importing these goods and services. More specifically, they are interested in knowing the domestic content of the sales of U.S. affiliates of foreign firms, which consist of the gross domestic product of these firms and their purchases of U.S.-produced goods and services from other firms. (An accurate measure of the domestic content, however, would require the collection of data on imported immediate goods by U.S. firms and related improvement in the U.S. input-output tables; see Recommendation 2-2 in Chapter 2.) The contribution of foreign affiliates of U.S. firms to the gross domestic product of foreign countries and the foreign content of the sales of these companies are also of interest and can be obtained from the proposed supplemental framework.

The proposed framework also sheds light on the international competitiveness of U.S. firms, a topic that has received considerable attention since the early 1980s. Because indicators of a country's international competitiveness have commonly involved only measures of cross-border trade, the decline in the U.S. share of world exports from the 1960s through the mid-1980s signaled to many that the United States was faring poorly relative to many other countries. One popular explanation for this loss in competitiveness stresses that U.S. firms have lost their lead in technology and managerial skills. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 states, for example, that there has been inadequate growth in the productivity and competitiveness of U.S. firms and industries relative to their overseas competitors. This legislation contains various provisions aimed at increasing U.S. international competitiveness, including changes in trade policy, measures to promote technology competitiveness, and steps to encourage better education and training for American workers. But the international performance of U.S.-owned firms relative to foreign-owned firms is indicated better by comparing the total cross-border and

|

6 |

BEA has recently estimated this figure as a separate exercise; see Lowe (1990). |

affiliates' sales by U.S. firms with those of their foreign counter-parts—and noting the relative growth rates of the various sources of sales —than by just comparing exports and imports.

The growth of intracompany trade, which is directly related to the rise in U.S. direct investment abroad and the increase in foreign direct investment in the United States, has also raised new issues concerning macroeconomic policy, the arbitrary valuation of exports and imports, evasion of taxes, and dumping practices. For example, a tighter monetary policy in the United States to curtail inflationary pressures is likely to restrain the investment activities of U.S. affiliates of foreign firms less than those of U.S. firms, since the former firms generally have easier access to foreign capital markets than U.S. firms. In intrafirm trade, there is a tendency to price traded goods to minimize a firm's tax liabilities, which yields misleading trade statistics and creates tax evasion problems for public authorities. For example, as of July 1991, some 30 corporations, including Apple Computer, BASF, Bausch & Lomb, Exxon, Hitachi, Nestl é, and Yamaha, had cases before the U.S. Tax Court that involved improper valuations by the companies to reduce their profits subject to U.S. taxes. It is also possible to carry out dumping under the guise of transfer pricing practices. The supplemental framework, which indicates the relative importance of intrafirm trade, informs public policy making in these areas.

The increased willingness of the United States to enter into special regional agreements with other countries is still another example of the value of the supplemental framework. In regional trade arrangements, such as the North American Free Trade Area, minimum regional content percentages for goods traded among members are established to minimize problems associated with differences in tariffs among member and nonmember countries. The supplemental framework facilitates such calculations for affiliates of foreign firms operating within the free trade area, as well as the enforcement of the negotiated rules.

IMPLICATIONS FOR EXISTING DATA SYSTEMS

Much of the data required for the supplemental framework are readily available from the balance-of-payments data, BEA's bench-mark and annual surveys on U.S. direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in the United States, and BEA surveys on trade in services. Development of the supplemental framework requires that the disparate data sets be integrated.

A key matter that arises in constructing the supplemental framework is how to define an affiliate. In compiling the balance-of-payments accounts, BEA regards a foreign affiliate as a foreign firm in which one person (in the legal sense that includes a firm) in the home country owns or controls 10 percent or more of the enterprise's voting securities. Consequently, under current practices, two or more countries can treat the same firm as a foreign affiliate. This will lead to double counting of the total sales and purchases if an affiliate is assigned to each country with a 10 percent or more ownership interest. One approach would be to allocate the sales and purchases of affiliates in proportion to the ownership interests of the different countries. Another approach is to include only those affiliates that are majority owned: that is, affiliates in which the combined ownership of those persons individually owning 10 percent or more of the voting stock from a particular country exceeds 50 percent. One could assign all sales and purchases of affiliates to countries with majority-ownership interests or only the proportions equal to the ownership interests. The increasing diversification of portfolios by pension funds and other institutional investors raises similar issues. Although these funds sometimes acquire 10 percent or more of the voting stocks of firms, they often do not attempt to exert control by proposing candidates for the firms' boards of directors. According to existing rules for determining foreign affiliates, if a U.S. firm owns 100 percent of a foreign firm, but the U.S. firm is, in turn, wholly owned by another foreign firm, the first foreign firm will be counted as a foreign affiliate by the U.S. firm, and again, indirectly, by the second foreign firm that owns the U.S. firm. These and other related issues should be considered in implementing the supplemental framework to avoid double counting.

Integration of disparate data sets under the proposed framework would parallel ongoing efforts undertaken by the United States and international organizations in improving existing statistical systems to better reflect changing global realities. Work is currently under way in the United States to move its national accounts to the U.N. system of national accounts (SNA) by the end of the 1990s. A central feature of the SNA is that it integrates the recording of the different types of market transactions in an economy. In addition to the income and product accounts, it includes consumption, investment, and saving measures, as well as input-output accounts, flow of funds accounts, and balance sheets (Carson and Honsa, 1990). The SNA is presently being revised to reflect improvements in economic accounting over the past two decades

and the changes in the international economic environment. The U.N. task force is working toward developing concepts, definitions, and statistical methods in the SNA that reflect the growing importance of foreign direct investment and the rise in intracompany trade of multinational corporations, among others. The purpose is to facilitate meaningful economic analysis and forecasting, as well as policy formulations. Other major objectives of the current revisions of the SNA and those of the revisions of the Balance of Payments Manual presently undertaken by the International Monetary Fund are to harmonize concepts and classifications of international transactions; their goals are to facilitate international comparisons, a topic that is further discussed in Chapter 2.

RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation 1-1 A supplemental statistical framework that integrates balance-of-payments data and data on affiliates' operations at home and abroad should be developed to better reflect the link between trade and foreign direct investment.