2

Extending the Comparability of International and Domestic Economic Data

Different classification systems, collection methods, and levels of detail are currently used to compile data on U.S. international trade in goods and services and capital flows. Still other classifications, collection methods, and levels of detail are applied to collect data on domestic production, employment, services, and financial activities. The disparateness of data sets has limited the analytical usefulness of existing data, especially for assessing the impact of international transactions on the domestic economy and its various sectors (Maskus, 1992). Comparability of domestic and international data is essential for maximal usability, particularly now that domestic and international economic activities have become increasingly connected.

COMPARABLE DATA: NEEDED BUT LACKING

Although detailed data on U.S. exports and imports are of considerable interest in themselves, business decision makers, government officials, and researchers often want to relate international trade data to domestic economic data. Domestic producers of a given product, for example, want to know not only the quantities of competing products that are imported, but also what share of the total domestic consumption of that product is represented by those imports. They also want to know what share of the total consumption of comparable products in various foreign countries are represented by their exports. And they are interested in the

changes in these import and export shares over time. Similarly, in considering whether to reduce tariffs and nontariff measures that protect a particular industry or whether to grant increased protection to an import-injured industry, public officials need to know both the volume of imports in the industry and its level of employment and production.

Private-sector and government researchers trying to understand the reasons for the competitive strengths and weaknesses of various industries need economic data that are classified on the same sectoral basis. They need information, for example, about physical capital, human capital and skills, and educational levels of labor in import-competing and export-oriented product industries, as well as information about such market features as the degree of concentration among firms and the importance of scale economies in different economic sectors. Furthermore, as the globalization of production continues, there is an increasing need for such comparable national and international information as the extent of trade in services, the value of U.S. direct investment abroad and of foreign direct investment in the United States, and volume of goods and services production by affiliates.

In the changing world economic environment, policy makers also need to know the extent to which the structure of U.S. industry has been affected by increased internationalization of the economy. How widespread is “the global factory”? How much has the mix of goods and services supplied by the United States to the world changed over time? To what degree has specialization shifted in today's markets? How well have U.S. industries adapted to the increased internationalization? What has been the impact on employment and occupational patterns by industry and regions of the country? Are there new or changed educational or skill requirements for U.S. workers? How well have public and private U.S. institutions met and responded to changes? Obtaining answers to these and to other questions about the performance of the U.S. economy requires that U.S. foreign trade and domestic data be comparable over time; comparable data among countries are also vital to understanding the increasingly global world economy.

U.S. FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC DATA

In contrast to the clear need for comparable domestic and international U.S. economic data is the reality of different classification systems for almost every data set. For example, data on U.S.

merchandise trade are currently classified under the international Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS), while domestic production is classified by the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes, which are unique to the United States. One major difference is that data on merchandise trade are classified by product, and many data series on domestic economic activity are classified by industry of establishment. Although comparisons of data on trade in goods and domestic production are possible through the use of concordances that artificially bridge the data sets, there are still significant differences between merchandise trade data and domestic economic data.

For services and financial transactions, it is extremely difficult to make any comparisons. Cross-border trade in services, for example, is broken down into only about 25 service categories, compared with 125 for domestic services. And sales of services by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms are classified by the industry of the affiliate: there is no detail by type of service. Meanwhile, some types of services —for example, transportation, communications, finance, and insurance —that are covered in international services data are not even covered in domestic data.

Other differences exist at almost every level of data collection and classification. For example, domestic production data are collected on an establishment basis, but direct investment data are obtained from enterprises. Also, data on sales of goods by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms and U.S. affiliates of foreign firms, on U.S. direct investment abroad, and on foreign direct investment in this country are recorded at one level (two- and three-digit) of the SIC, while data on merchandise trade and most domestic activities (such as production and employment) are available at a different level (four-digit) of the SIC. Moreover, although some direct investment data are classified by “industry of sales,” most data are available only by the primary industry of the affiliate. These differences in the level of detail and classification schemes at which disparate data are compiled mean that different sectors of the internationalized U.S. economy can be related to one another only at a fairly aggregate level, not at the level most needed by public and private decision makers.

Adequate data are also lacking on the trade in goods and services used as intermediate inputs in domestic production activities. Analysts to date have only been able to make imprecise estimates from the current input-output table of the value of intermediate inputs used by any industry that are not produced

domestically. The input-output tables do not distinguish between imported products and domestically produced products used as intermediate inputs. Yet having accurate information about the foreign content of any product is becoming increasingly important not only as an indicator of the rising trend in affiliated transactions and a guide in bilateral and multilateral trade negotiations, but also in understanding the transformation of the economy.

INTERNATIONAL DATA

The situation regarding international comparability of data has improved significantly since January 1989, when the United States adopted the international HS for classifying U.S. merchandise trade. More than 80 other countries have now adopted the HS, making it easier to compare merchandise trade among countries. But comparisons of other U.S. international economic activities with those of other nations remain difficult. International comparability of services data is hampered by differences in definitions, classifications, and coverage among countries. Historically, worldwide compilation of balance-of-payments statistics has focused on certain major categories of services, such as trade and transportation. Data on other services are fragmentary, with little uniformity among countries in the range of services covered. Few countries collect international services data in the same detail as the United States, and no other country currently conducts regular surveys of services sold through affiliates of multinational firms (establishment transactions) (Ascher and Whichard, 1992). These obstacles also apply to international comparisons of data on capital transactions, for which differences in concepts, definitions, and coverage among countries are significant.

Although the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the Bank for International Settlements have established various statistical frameworks to compile data on international trade and finance from different countries, such compilations are often developed only at aggregate levels. Comparable international data at greater levels of detail are not available due to differences in coverage, definitions, concepts, and methodologies.

Work is currently under way to further harmonize the concepts and classifications for international transactions contained in the International Monetary Fund's Balance of Payments Manual

and in the U.N. system of national accounts (SNA). This effort at further harmonization, which began in the 1980s and is now in the final stages of revisions for both systems of accounts, is seen as promoting the consistency and enhancing the analytic potential of both systems. Among major issues that are being addressed are the delineation of resident entities; the distinction among commodities, nonfactor services, factor and property income, and current transfers; the treatment of certain imputed flows, such as reinvested earnings on direct investment; and valuation. Because the United States intends to move its national accounts closer to the SNA and to revise its international accounts in light of the forthcoming new edition of the Balance of Payments Manual, the harmonization of the two sets of international guidelines moves work on the U.S. national and international accounts in the same direction. For the international accounts, it is envisaged that the United States will have considerable work to do to introduce a fully integrated system of stocks and flows, which is a theme of the SNA that is being carried into the new Balance of Payments Manual, and to introduce a more detailed set of accounts for travel, transportation, construction, insurance, finance, other business services, and other personal services.

Meanwhile, attempts to establish a standardized format or classification system for international services, similar to the HS for merchandise trade, are currently being made at the United Nations, where the central product classification (CPC) system is being developed for this purpose. Other efforts to refine concepts and definitions of international services and direct investment are being undertaken by the OECD, the Statistical Office of the European Communities, and the Voorburg Group (organized informally under the auspices of the U.N. Statistical Office to establish a new services unit to coordinate the work on services statistics within the OECD and with other international organizations). OECD also has recently completed a detailed compilation of services trade statistics of member countries covering 1970 to 1987, attempting to put them on a comparable basis.

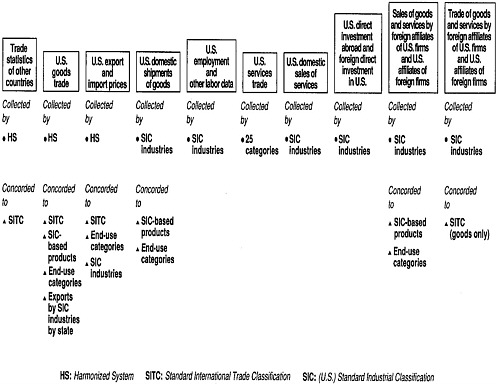

It will be valuable for U.S. public and private decision makers if current international efforts to harmonize economic data among countries are matched by similar pursuits to improve domestic data and make them comparable to data on international transactions. The next sections of this chapter describe data sets that warrant particular attention; their different classification schemes are discussed below and shown in Figure 2-1.

MERCHANDISE DATA

U.S. AND OTHER COUNTRIES DATA

One obvious requirement for an adequate trade data system is the ability to compare a country's own merchandise trade with that of other countries by product and industry categories. Until recently, such comparisons required the use of concordances between the unique U.S. import and export classification systems and a trade classification system developed under United Nations auspices, the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC). The situation changed on January 1, 1989, when the United States adopted a new classification system, the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS), developed by an international group of customs and statistical experts.1 Because many countries also now use the HS, it is possible to directly compare trade among countries in about 5,500 product groups.

The changeover has created problems, however, for those who want internationally comparable trade figures over a long period of time. While trade on an HS basis has been estimated by the Census Bureau and the International Trade Commission for the period 1983-1988, this series is only a rough estimate of actual trade during these years classified according to the new system. For example, in allocating shares when goods within a former product group are distributed among more than one product group under the HS system, the allocation weights based on the world trade in the products are applied to each individual country.

PRICE INDEXES FOR IMPORTS AND EXPORTS

Users of time series of merchandise import and export data invariably want price indexes for traded goods in order to compare real changes in trade over time. Other users are interested in price data for analyzing changes in a country's terms of trade. For imports, price indexes have been available only since September 1982; for exports, price indexes have been available since September 1983 (for details, see Alterman, 1992). The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) now collects quarterly import and export price data on about 22,000 products from more than 8,300 companies.

|

1 |

The pre-1989 import classification system was the Tariff Schedule of the United States Annotated (TSUSA), while the export system was the Statistical Classification of Domestic and Foreign Commodities Exported from the United States (Schedule B). |

Since January 1989 it has published import and export price indexes on a monthly basis.

Before monthly import and export price indexes became available, time series of trade in real terms were usually constructed by deflating figures using unit-value indexes produced by the Census Bureau as a by-product of the collection of U.S. merchandise trade data. The problem of shifts in the composition of industry products over time and the differences among the sets of goods produced, exported, and imported in an industry made this an unsatisfactory procedure. Many years ago, the Interagency Committee on Measurement of Real Output (1973) recommended that price data from the BLS wholesale and industrial price index programs be used more for deflation in the absence of import and export price indexes than the export and import unit-value indexes.

The BLS publishes import and export price indexes by three classification structures: SITC, SIC, and BEA end-use categories.

DOMESTIC PRODUCTION AND IMPORT AND EXPORT DATA

Another basic requirement for an adequate trade data system is the classification of imports and exports on the same basis as the classification of information on domestic production. In the United States, this is accomplished by rearranging the classification system on which production data are collected and reclassifying trade data by that system.

The basic unit for collecting production data is an establishment, an economic unit located at a single physical site. The Standard Industrial Classification (SIC), which is used by the United States to classify establishments by industry, classifies largely on the basis of two factors: the specific activity performed by the establishment and the nature of the customers served. The general objective is to establish industries that are relatively homogeneous in both their inputs and outputs. The latest classification system (1987) divides economic activities by agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and various service sectors (the first digit of the code) and then into more detailed breakdowns, ending with 1,005 four-digit industries. Since a particular establishment assigned to a specific four-digit industry may produce more than one product—for example, a plant producing mainly aluminum castings may produce some copper castings—the Census Bureau has developed an SIC-based system (up to eight digits) that classifies by product. Unlike the four-digit SIC industry data, the four-digit SIC-based product data consist only of shipments of the primary

products of the industry, including sales of these products by establishments classified in other industries, but excluding secondary products of establishments in the industry.

Since import and export data are classified by product under the HS, trade data can be related to the product codes of the expanded SIC system. Nonetheless, trade codes frequently lump together products that bridge two or more of the five-digit SIC product codes. When it appears that assigning the entire amount of the traded good to a single product code would significantly distort the import or export data, five-digit product codes are combined, and trade in the good is assigned to the more comprehensive code. The resulting combination of one or more five-digit SIC product codes yields the “SIC-based trade classification system.” Obviously, classifying import and export data by this system produces a far from perfect match with domestic output data.

The Census Bureau's periodical U.S. Commodity Exports and Imports as Related to Output presents the results of classifying trade and output data by the SIC-based trade system at the four-and five-digit level. The latest edition, issued in June 1990, covers 1985 and 1986. For some import-sensitive industries, however, the Census Bureau publishes comparisons of exports, imports, and production at the seven-digit level of SIC-based detail in its perodical Current Industrial Reports, and these reports appear monthly, quarterly, and annually, depending on the industry. The International Trade Administration (ITA) of the Department of Commerce also constructs series of imports, exports, and domestic shipments at the four-digit SIC-based level and has calculated ratios of imports to new supply (domestic shipments plus imports) and exports to shipments back to 1972. These data are published in part in its annual U.S. Industrial Outlook.

Using COMPRO, a computerized database on U.S. foreign trade maintained by ITA, federal government analysts could obtain SICbased import and export data at up to the eight-digit level for the period 1978-1988. From 1989 onward, however, data in this bank are available only on a four-digit SIC-based level. The Census Bureau stopped supplying post-1988 SIC-based import and export data at up to the eight-digit level because of problems in data quality associated with the conversion to the HS. COMPRO also provides time-series trade data classified on the basis of the HS, TSUSA, SITC, and end-use categories.

Nongovernment officials and researchers have had difficulty in recent years in matching imports, exports, and production at the four-digit SIC-based level. Through 1984, the Census Bureau pro-

vided import and export data at a detailed SIC-based level in two volumes, but they were discontinued for budgetary reasons; the data are available on microfiche. Some users report it is so difficult to read the data on microfiche that they cannot be used for developing comprehensive time series. The Census Bureau plans to provide trade data at the four-digit SIC-based level on CD-ROMs (compact disk-read only memory).

In the Annual Survey of Manufactures, the Census Bureau has asked establishments since the 1960s to report a single figure for the value of products shipped for export during the year. These data are then adjusted for underreported exports by using the trade data collected directly by the Customs Service and the Census Bureau to derive establishment exports of manufactured goods by three-digit SIC industry codes. The data are also reported by state on a two-digit SIC industry basis. Efforts to obtain export data by state have also been facilitated by including a question relating to state of origin on the shippers' export declarations (SEDs) collected by the Census Bureau. A similar question was included for the state of imports, but, because the state of the importer or broker office responsible for the paperwork was being listed rather than the state for which the merchandise was destined, the reporting of this information was suspended pending improvements in collection methodology. Since July 1991 the Customs Bureau has required that import documents report the state to which imported merchandise is destined.

IMPORT AND EXPORT DATA AND EMPLOYMENT, CAPITAL, AND OTHER ESTABLISHMENT DATA

When BLS collects data on employment in its monthly survey, it does not ask establishments in a particular SIC four-digit industry code to list the number of employees by product or product type, probably because employers usually do not keep employment records on this basis. The same is true with respect to figures on capital stock. Thus, it is not possible to relate trade data (classified on a four-digit SIC-based level) to data on such economic variables as employment, skill levels, wages, hours of work, earnings, turnover rates, productivity, unemployment, investment, and capital stock.

Other rich sources of data on the economic and social characteristics of the labor force by SIC industries are the Current Population Survey (annual) and the decennial census. These data provide a variety of information on characteristics of employees, such

as educational level, age, occupation, income, sex, race, and marital status. But the level of industry detail has changed considerably over time. Even today, data for agriculture, mining, and construction are presented only at the two-digit SIC level. Information for other sectors are generally given at the three-digit level.

CLASSIFICATION OF INTERMEDIATE INPUTS

As national economies become increasingly internationalized, a greater proportion of imported goods are used as intermediate inputs in the production of other goods and services rather than as final goods and services by consumers, investors, or governments. Unlike a number of industrial countries, however, the United States does not collect information on the extent to which industries use as intermediate inputs imported goods that are substitutable for domestically produced goods. Imports are not distinguished from domestically produced substitutes in the input-output tables constructed by the Department of Commerce that indicate the intermediate and final uses of the primary products of more than 500 SIC industries. Consequently, it is possible neither to determine exactly the domestic content of any product nor to estimate the direct and indirect increase in imports associated with a given increase in demand for that product.

Such information is important not only for determining the extent of the internationalization of domestic production, but also for the successful implementation of policies aimed at protecting domestic industries subject to injurious import competition and at helping domestic industries become more competitive. Although it is not feasible to determine the country source of every intermediate input, a significant share of the imports used as intermediate inputs could be allocated to the proper industry by relying on the import records of major industry producers and their main suppliers. These companies could report these allocations as part of the 5-year economic censuses and their annual updates.

SERVICES DATA

Until 1987, information on cross-border transactions in services was limited to a comparatively small number of categories, such as royalties and licenses fees, travel, passenger fares, freight, port services, reinsurance, telecommunications, and film rentals. As of 1987, however, data on trade in services are available for about 25 separate categories, covering various types of business, professional, and technical services in particular detail. As discussed in

Chapter 5, continued efforts are needed to develop more detailed descriptions of traded services codes. Additional work is also needed in the ongoing efforts to develop price indexes for internationally traded services.

Benchmark data on domestically produced services by 174 fourdigit SIC service industries are provided in the quinquennial economic censuses, which cover retail trade, wholesale trade, and selected other services. Yet some major services are excluded from these economic censuses, such as transportation, communications, finance, and insurance. 2 Data collected in the economic censuses cover employment, value of output, capital stock, investment, and cost of materials used.

Employment and payroll data for service sectors are available on an annual basis from the BLS monthly survey of establishments, as are data on the value of services provided, based on records of the Internal Revenue Service and the Annual Survey of Selected Service Industries. BEA also annually estimates real GNP originating in selected two-digit service sectors.

The classification system for collecting data on traded services does not directly match the SIC industry basis on which information on domestically produced services is assembled. For some traded services categories, such as royalties and license fees, matching would not be appropriate. For many traded services, however—especially business, professional, and technical services—it would be valuable to compare the volume of international trade in services with the domestic output of those services, just as trade in goods is compared with the domestic production of these goods.

At present, the relatively small number of traded services categories does not make it too difficult to compare these with broad SIC domestic service groups, but as more and more traded services are distinguished, the comparability issue will become more important. In particular, data on the production of domestic services should be classified by SIC-based product codes so that they can be easily compared with data collected on traded services.

To improve domestic services data, the Census Bureau has expanded its quinquennial economic censuses and its annual sample surveys to cover a greater number of services. In addition, the Federal Reserve Board has recently developed experimental output indexes for services, similar to its indexes of industrial production. Extension of these efforts to cover U.S. international

|

2 |

The Committee on National Statistics of the National Research Council has recommended that benchmark data for these services be developed; see Helfand et al. (1984). |

services transactions would enhance comparability of domestic and international data on services.

OTHER DATA

SALES OF GOODS AND SERVICES BY FOREIGN AFFILIATES

In its surveys of U.S. direct investment abroad and foreign investment in the United States, BEA collects data on the sale of goods and services by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms abroad by two- and three-digit SIC industries and also the sales by U.S. affiliates of foreign firms in the United States by two- and three-digit industries. Data on employment, capital stock, investment, etc. are also collected on affiliates. Detailed information is provided every 5 years, with annual surveys being used to augment the benchmark surveys. Data on merchandise (but not services) trade between affiliates and the home country of the parent are collected only at the level of one-digit SITC codes in benchmark surveys. Although trade between foreign affiliates and their home countries at this level can thus be compared with total U.S. imports and exports of these products, trade data at a much more detailed level are needed in view of the economic importance of foreign affiliates (30 percent of U.S. exports are to foreign affiliates of U.S. firms). Of course, U.S. merchandise trade must be reclassified on an SITC basis, too. The HS rather than SITC would be a better basis for collecting trade data. The Census Bureau currently collects information on merchandise exports between related parties on the SEDs, but funds have not been appropriated for tabulation or analysis of the data.

DIRECT INVESTMENT

Data on U.S. direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in the United States are collected by BEA in detailed quinquennial surveys and in less detailed annual and quarterly surveys. Such information as the total value of foreign investments, annual investment, and employment by foreign affiliates is available for both U.S. direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in the United States from these surveys on a two- and three-digit SIC industry basis that covers both goods and services sectors. These data, together with data on domestic investment, can be used to measure the extent to which the capital stock of the United States is being internationalized as well as the extent to which the United States is penetrating foreign markets through investment activities.

Comparing growth rates of direct investment and goods and services trade is also useful in understanding the internationalization of national economies. To obtain more information, the data on investment need to be collected on a four-digit SIC industry basis. The possibility of reclassifying those data to four-digit SIC product basis should also be explored.

NATIONAL TRADE DATA BANK

The National Trade Data Bank (NTDB) is a depository database containing trade and export promotion information from 15 federal agencies. Established by the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, the NTDB assembles economic, demographic, social, and other statistics of the United States and other countries that are of use to promote U.S. exports. In addition to the Census Bureau's merchandise trade data, the NTDB provides data on international transactions and the quarterly NIPA compiled by BEA; data on exchange rates and foreign interest rates gathered by the Federal Reserve Board; international labor and price statistics prepared by BLS; and other data series on the U.S. industrial outlook. Figure 2-2 shows the information programs accessible through

FIGURE 2-2 National Trade Data Bank (NTDB) Information Programs

|

Central Intelligence Agency Handbook on Economic Statistics The World Factbook Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Services Foreign Production Supply and Distribution of Agriculture Commodities Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration (ESA), Bureau of the Census Exports from Manufacturing Establishments Merchandise Trade—Imports (Country-Commodity) Merchandise Trade—Exports (Country-Commodity) Merchandise Trade—Imports (Commodity-Country) Merchandise Trade—Exports (Commodity-Country) Total Mid-Year Populations and Projections through 2050 Trade and Employment Department of Commerce, ESA, Bureau of Economic Analysis Fixed Reproducible Tangible Wealth Estimates Foreign Direct Investment in the U.S.: Position, Capital, Income International Service National Income and Product Accounts, Annual Series National Income and Product Accounts, Quarterly Series Operations of U.S. Affiliates of Foreign Companies |

|

Department of Commerce, ESA, Bureau of Economic Analysis—continued Operations of U.S. Parent Companies and Their Foreign Affiliates U.S. Assets Abroad and Foreign Assets in the U.S. U.S. Business Acquired and Established by Foreign Direct Investors U.S. Direct Investment Abroad: Position, Capital, Income U.S. Expenditures for Pollution Abatement and Control (PAC) U.S. International Transactions (Balance of Payments) U.S. Merchandise Trade (Balance of Payments Basis) Department of Commerce, ESA, Office of Business Analysis NTDB BROWSE Manual Sources of Trade Information and Contacts Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration (ITA) Business America A Basic Guide to Exporting Domestic and International Coal Issues and Markets EC 1992: A Commerce Department Analysis of EC Directives, Volumes I-III Foreign Traders Index Market Research Reports Country Marketing Plans Industry Sector Analyses Foreign Economic Trends North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) Information Understanding U.S. Foreign Trade Data U.S. Industrial Outlook Department of Commerce, National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) GATT Standards Code Activities of NIST Organizations Conducting Standards-Related Activities Standards, Certification and Metric Information Program Department of Energy International Energy Database Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics International Labor Statistics International Price Indexes Department of State Reference Guide to Doing Business in Central and Eastern Europe Export-Import Bank of the United States Export-Import Bank of the United States, Quarterly Report Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Foreign Spot Exchange Rates Foreign 3-Month Interest Rates Stock Price Indices for the G-10 Countries U.S. 3-Month CD Interest Rates Weighted Average Exchange Value of the Dollar U.S. International Trade Commission Trade Between the U.S. and Non-Market Economy Countries Overseas Private Investment Corporation OPIC Program Summaries Office of the U.S. Trade Representative National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers Trade Projections Report to the Congress University of Massachusetts, MISER State of Origins Exports |

the NTDB. Although this data bank has undoubtedly eased problems of data access for trade analysts, other data are needed to gauge the international positon of the U.S. economy and its various sectors. Such data include measures of productivity, costs, profit rates, capital costs, and overall competitiveness and measures of tariffs and other trade barriers. The data are particularly needed to facilitate valid international comparisons.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 2-1 The United States should take the lead in international cooperative efforts to build coherent comparable worldwide accounts through standardizing data concepts and methodologies on production, trade, employment, and investment and establishing a statistical framework that captures changing international commercial relations.

Recommendation 2-2 As part of the quinquennial surveys, the Census Bureau should collect data on purchases of imported goods and services. The Bureau of Economic Analysis should use the data to strengthen its program on the compilation of the U.S. input-output tables.

Recommendation 2-3 Data at the four-digit SIC industry level, compiled in most cases on a four-digit SIC product basis, should be collected not only on the domestic production of goods, but also on the domestic production of services, the production of goods and services by foreign affiliates, and foreign direct investment so that data on international trade in goods and services can be related to these data. Quantitative and qualitative information about the use of labor, capital, and intermediate inputs in producing goods and services should also be collected at the four-digit SIC level. Data on the trade of affiliates should also be collected in greater detail.

Recommendation 2-4 COMPRO should be made available to all users through its inclusion in the National Trade Data Bank.

Recommendation 2-5 Measures of productivity, costs, profit rates, capital costs, and overall competitiveness and other measures of tariffs and trade barriers should be included in

the National Trade Data Bank to facilitate valid international comparisons.

Recommendation 2-6 Efforts to measure traded services in greater detail should continue along with efforts to develop price indexes for internationally traded services. The United States should participate fully in international efforts to develop a common classification system for traded services for all countries.