Highlights from the Work of Federal Agencies

Elements of healthy and sustainable communities include access to healthy foods, safe and affordable housing, environmental quality, and safe transportation. For the first workshop panel, representatives from four federal departments or agencies provided examples of successful interagency collaboration in the areas of environmental health, transportation, military health, and housing. Florence Fulk, Chief of the Molecular Ecology Research Branch in the Office of Research and Development at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) discussed how the EPA is linking health impact assessments and community research to decision making. Beth Osborne, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Transportation Policy at the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), discussed the relationship between transportation and health and highlighted several DOT initiatives to evolve transportation. Captain Kimberly Elenberg, Deputy Director of Population Health and Medical Management in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs in the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), described Operation Live Well, a DoD education, outreach, and behavior change initiative to improve the health and well-being of service members and their families. Finally, Jennifer Ho, Senior Advisor in the Office of the Secretary at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Developoment (HUD), described two HUD grant programs aimed at fostering healthy and sustainable communities. An open discussion moderated by Dawn Alley, Senior Policy Advisor in the Office of the Surgeon General at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, followed the panel presentations.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

A sustainable community is one that protects the health and well-being of all residents, is economically vibrant with a return on public investments, provides new business opportunities, and conserves natural resources and open space, explained Florence Fulk. When communities are considering new development (e.g., transportation plans), they often focus on how it will achieve only one of these objectives. The EPA Sustainable and Healthy Communities (SHC) program, one of six key transdisciplinary research programs in the EPA Office of Research and Development (ORD), is based on the principle that a systems approach will improve a community’s ability to address all of these objectives simultaneously. The vision of the SHC program is “actionable science for communities,” Fulk said. The program seeks to inform and empower communities to include human health, economic, and environmental factors into their decisions and policies in a way that fosters community sustainability. Based on input from communities about their needs, the program focuses on four sectors: transportation, infrastructure, land use, and waste management.

Health Impact Assessments in Community Decision Making

One approach to integrating health concerns into policy making is the health impact assessment (HIA) (see Box 3-1). An HIA can provide state and local decision makers with the scientific data, health expertise, and public input that they need to factor public health considerations into the development of non-health plans, policies, or projects. The EPA’s SHC

BOX 3-1

Major Steps in Conducting a Health Impact Assessment (HIA)

- Screening: Identify projects for which an HIA would be useful.

- Scoping: Identify which health impacts to consider.

- Assessing risks and benefits: Identify which people may be affected and how they may be affected.

- Developing recommendations: Suggest changes to proposals to promote positive or mitigate adverse health effects.

- Reporting: Present the results to decision makers.

- Evaluating: Determine the effect of the HIA on the decision process.

SOURCE: Fulk presentation (September 19, 2013) and originally from CDC, 2010.

program can provide the tools, models, and approaches to support HIAs, and data from HIAs can inform SHC research about the issues and decisions communities face, as well as how communities address the issues with regard to health, economic, and environmental factors. Over the past 10 years, Fulk said, HIAs have been used to inform decisions about, for example, mass transit, highway, and bridge design; housing and energy assistance programs; comprehensive planning and growth policies; and energy programs and natural resource management (including fossil fuel exploration and development, renewable energy, and water management policies).

As an example, Fulk described the HIA for the Proctor Creek Boone Boulevard Green Street Project, which is evaluating the potential positive and negative public health impacts of the project design. The city of Atlanta, Georgia, is considering the implementation of a green infrastructure project along Boone Boulevard in concert with a lane reduction project. The green street project will affect two communities that are suffering from a number of environmental problems, including pervasive flooding, impaired water quality, poverty, derelict properties, and aging infrastructure. The HIA is being led by EPA’s Region Four Office of Environmental Justice and Office of Research and Development, in partnership with the Fulton County Health Department, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and others (government agencies, universities, nongovernmental organizations, community organizations) across multiple sectors.

Green infrastructure, Fulk explained, is a nontraditional approach to infrastructure using natural processes (e.g., vegetation, soil filtration, shading, storm water management) to maintain healthy waters, protect the environment, and also support sustainability. Some of the green infrastructure approaches suggested for the Boone Boulevard Project include planter boxes and an urban tree canopy.

From the perspective of the SHC and EPA research, Fulk concluded, this HIA provides a model of interagency collaboration at the local, state, and federal levels. SHC is gaining experience in the application of HIAs in other environmental decision-making processes and helping to create a better understanding of the direct and indirect public health benefits from implementing green infrastructure.

A good transportation system can support active living, reduce air and water pollution, and give people safe access to the things they need, including health care, jobs, and other opportunities, said Beth Osborne.

Although this is well understood, these considerations are not always taken into account in our transportation systems, she said.

Eighty percent of DOT program funding goes to state DOTs, which have discretion on how that money is spent, Osborne said. State DOTs oversee state highways, but some will also oversee transit programs, and some even ports and airports. State transportation planners and engineers are focused on transportation efficiency (generally long distance rural routes that are straight, clear, and fast) and, in most cases, do not involve land-use authorities. Local governments are focused on development around the state-developed roadway system, often in a way that was never envisioned by the transportation planners.

For five decades, people traveled extensively by car, but since the late 1990s, people are making different transportation choices. Osborne said the system is not supporting these changes because land-use decisions are being made at the local level, and transportation decisions are being made at the state level, and the two levels do not always communicate. The way roadways are designed has a huge impact on behavior. People in one community may walk for many blocks to a grocery store, while in another neighborhood they may drive to a grocery store only a block away because it is across a very busy road that is too dangerous to cross on foot. People may wish to bicycle to work, but have no safe route to take. Lifestyles have changed and the transportation system has not.

Osborne described several DOT initiatives to evolve transportation systems (reiterating that the majority of funding and decision making resides at the state level). The DOT Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) Program awards competitive, discretionary grants for infrastructure projects. In Boston, for example, TIGER funds are being used to redesign and retrofit streets to move more people by bicycle and on foot. DOT is profiling best practices of metropolitan planning organizations and the work of some states that have developed system performance measures. DOT has also joined with HUD, EPA, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in coordinating agency programs that support livability in a community, which is defined as having transportation choices, housing choices, and destinations close to home.

These types of livable communities support healthy living, Osborne said, but they also save people and the government money. An emerging problem is that property values in these communities can increase rapidly, resulting in the functional exclusion of the people who most need non-motorized transportation. Supply and demand are still not balanced, she noted, as the transportation solutions being put into place are still not meeting market demand. To help inform both planners and residents, DOT is working with HUD on a Housing Plus Transportation Afford-

ability Index, a tool to assess the affordability of a home relative to both the cost of the home and the transportation costs for people to get where they need to go from that home. Similarly, DOT is working with CDC on a Transportation and Health Index to look at the impact of different transportation types on health.

In closing, Osborne noted that in the reauthorization of DOT, Congress has put a new focus on performance. The performance measures put forth are focused on issues such as reliability of the system, congestion, and air quality, but there are no health performance measures.

Operation Live Well

Similar to national statistics, approximately 65 percent of the health care costs for the DoD are related to noncommunicable diseases, said Kimberly Elenberg, and many of those are aggravated by behavior choices, obesity, and tobacco use. These conditions not only drive up health care costs, they directly affect the ability of DoD to meet its mission,1 impacting resiliency and readiness. Concerns about the health of a family member also affect a service member’s ability to focus on his or her mission.

Operation Live Well is DoD’s education, outreach, and behavior change initiative designed to improve the health and well-being of members of the defense community. This multiyear strategy was influenced by, and aligns with the U.S. National Prevention Strategy and is specifically tailored to the unique environments and circumstances of military service. Operation Live Well brings together all of the resources and capabilities of the entire military community to promote health, Elenberg said. The strategy is divided into three phases. Phase 1 is an information, education, and outreach campaign, including the Healthy Base Initiative (discussed on p. 18). Phase 2 involves rigorous evaluation of programs, services, and tools and expansion of those that are shown to be most effective in supporting a healthy lifestyle. Phase 3 will be the implementation of a long-term effort to institute sustained behavior change, such that healthy living is the easy choice and the social norm.

________________

1 The mission of the U.S. Department of Defense is “to provide the military forces needed to deter war and to protect the security of our country” see http://www.defense.gov/about (accessed March 10, 2014).

Healthy Base Initiative

The Healthy Base Initiative is a demonstration project being conducted at 14 military installations around the world (including Air Force, Army, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard). The results of this initiative will inform the strategy implemented in phase 3, Elenberg explained. The primary objectives of the Healthy Base Initiative are to optimize health and performance, improve readiness and reduce health care costs, and provide DoD with the framework for best practices that support improvements in population health. As many service members do not live on base, the initiative is conducted in partnership with communities surrounding installations.

Initially, the project will assess the physical environment, existing health and wellness initiatives, and current health behavior of the population. The focus will be on initiatives that improve nutritional choices, increase physical activity, promote healthy weights, and decrease tobacco use. For example, can the walkability or bikeability of the military installations be improved? Can the selections at the dining facilities be improved, or can the open hours be extended so that people do not have to resort to using vending machines or fast food after hours? The bottom line is how, from a systems perspective, to make the healthy choice the easy choice.

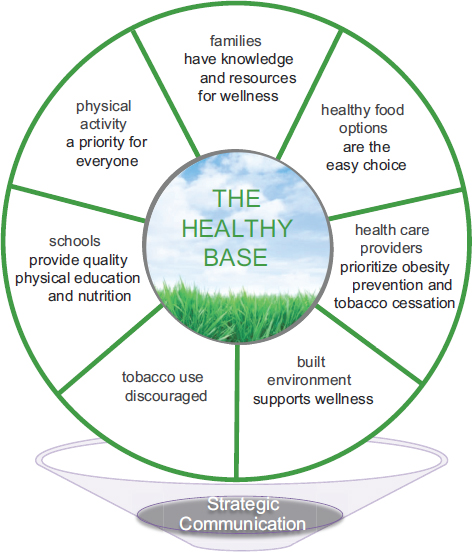

The framework for the initiative (see Figure 3-1) is complemented by a strategic communication campaign. The key to success is a Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach, and intersectoral and cross-sectoral collaborations, with the goal of making this initiative meaningful to many different people, Elenberg said. Those who are highly motivated, and have a high ability to lead a healthy lifestyle, can serve as leaders in the community and work at a grassroots level to help motivate and mentor others.

Elenberg highlighted a few of the initiative’s findings to date. Military food and nutrition services require major changes to provide healthful offerings. Onsite facilities, vending, and fast food outlets need to offer more healthy choices, and to offer them more prominently, she said. With regard to active living, there are well-equipped and conveniently located fitness centers and recreational programs for military personnel and their families. There are opportunities to increase physical activity in schools and to improve the ability to make healthy choices in the cafeterias. Although there are many primary prevention activities already occurring in military communities, Elenberg stated that increased communication and strategic coordination among them are expected to lead to more effective use of resources. Community understanding of and access to these services and resources needs to be improved through strategic communication and mobilizing for action through planning and partnership with health promotion councils.

FIGURE 3-1 Framework for the Healthy Base Initiative.

SOURCE: Elenberg presentation, September 19, 2013.

Our home is where we live, it is a part of the community in which we live, and everything that is going on in the community around us affects our health and our well-being, said Jennifer Ho. Housing is a means to health and well-being, and health comes into play in many of the activities of HUD. Ho quoted HUD Secretary, Shaun Donovan, who said that

“sustainability means tying the quality and location of housing to broader opportunities, like access to good jobs, quality schools, and safe streets. It means helping communities that face common problems start sharing solutions. It means being a partner to sustainable development, not a barrier.” As mentioned by Osborne, HUD is working in partnership with DOT and EPA to foster healthy, sustainable communities.

Ho described two grant programs administered by the HUD Office of Sustainable Housing and Communities. Regional planning grants, totaling $170 million in 2010 and 2011, were awarded to improve regional planning efforts that integrate housing, land use, economic and workforce development, and transportation and infrastructure investments to address economic competitiveness and revitalization; social equity, inclusion, and access to opportunity; energy use and climate change; and public health and environmental impact. Communities participating in the regional planning grant program complete the Fair Housing and Equity Assessment, which helps them assess where people live according to race and economic status, and integrate those data with data on access to community assets, to understand the potential effect of policies on community members.

Community Challenge Grants, totaling $70 million in 2010 and 2011, enable communities to foster reform and reduce barriers to achieving affordable, economically vital, and sustainable communities, stated Ho. For example, grants promote mixed-use development and repurposing of existing buildings. Funded activities have included amending or replacing local master plans, neighborhood plans, corridor plans, zoning codes, and building codes. Between the 2 grant programs, HUD is currently supporting work in 48 states and the District of Columbia that covers areas where more than 133 million Americans live.

In assessing the sustainability of communities, HUD looks at a variety of flagship indicators. Examples described by Ho included

- Transportation choice: percentage of workers commuting via walking, biking, transit, or rideshare.

- Housing affordability: percentage of rental units and owner units affordable to households earning 80 percent of HUD area median family income.

- Equitable development: housing plus transportation affordability (proportion of household income spent on housing and transportation costs); access to healthy food choices (percent of total population that reside in a low-income census tract with a supermarket more than 1 mile away for urban or 10 miles away for rural populations); and access to open space (percent of

-

population with a park within 0.5 mile for urban or 1 mile for rural populations).

- Economic resilience: economic diversification; general local government to revenue ratio.

- Growth through reinvestment: net acres of agricultural and natural resource land lost annually to development per new resident.

In closing, Ho stressed that collaboration is essential. Many efforts across agencies and across initiatives have similarities. Interagency activities on homelessness, for example, are similar in some ways to the activities on sustainable communities. There are lessons learned and best practices that can be shared and opportunities to make better use of funding through partnerships. Collaboration across agencies requires commitment and support from leadership, she said, and staff need to become familiar with other programs and identify intersection points. Ho referred participants to the Partnership for Sustainable Communities website for more information about the HUD, DOT, and EPA partnership.2

In the discussion that followed the panel presentations, individual panelists and workshop attendees expanded upon a range of topics, with particular interest in how to foster revitalization without inadvertently furthering inequities, the cost of HIAs, the costs and benefits of intersectoral collaboration, the issue of livability initiatives beyond urban areas to rural areas, the role of communication, and an exploration of leverage points in the decision-making process.

Fostering Revitalization Without Furthering Inequities

Individual participants raised concerns about how revitalization in urban areas is leading to increased costs of rent, food, and other essentials, forcing out many long-time residents. As pointed out by roundtable member Phyllis Meadows, successful initiatives often result in displacement and the furthering of inequities. Ho highlighted the importance of considering the potential impacts of policies in creating geographic segregation. Osborne added that people who work in these sought-after neighborhoods (such as child care providers) are often unable to afford to live close to where they work. There is significantly higher demand for these neighborhoods than there is supply. Policies need to support

________________

2 See http://www.sustainablecommunities.gov/index.html (accessed March 7, 2014).

the retrofitting of more communities as desirable and healthy places to live, she said. Fulk reiterated that one of the core values of the HIA process is equity and that an HIA of a neighborhood development plan or policy should identify potential displacement of lower income families and make recommendations to mitigate that potential. Osborne noted that DOT recently updated its New Starts Guidance for transportation investments and, in collaboration with HUD, is working to put the affordable housing element into the evaluation process for transit projects. The intent is to ensure that people who are transit-dependent will still be able to access the transit as it is planned in the project. A healthy and sustainable community is one that is both racially and economically diverse, Ho said, and that vision should be stated at the outset of any project. Elenberg suggested that there needs to be outreach to let people know that their voices are important and to motivate people to participate in influencing and shaping their communities. Moderator Dawn Alley added that eliminating health disparities is one of the four strategic directions of the National Prevention Strategy, and the other three (promoting healthy and safe community environments, promoting empowered people, and increasing linkages between clinical and community preventive services) each have an equity dimension.

A participant suggested several state- and local-level practical strategies to help establish a balance between gentrification and concentrated poverty in a community. Inclusionary zoning, for example, requires land-use planning to include mixed income housing types (not just single unit homes); state guidelines can require mixed income opportunities for infill redevelopment3; and metrics for transportation plans should focus on ensuring that transportation is available to those with the lowest income. She also suggested the need for incentives for developers to build the equity component into plans. Ho responded that the HUD planning grants and challenge grants do create incentives to change behavior, and thereby change community outcomes. The fundamental issue is support from Congress with funding for the grant programs. Osborne added that while land-use decisions are local the federal government’s role is to make sure that communities have the tools and the data to make the right land-use decisions (through programs such as the Planning Grants). Many communities are working with transportation data that is more than a decade old. Activities such as updating their planning models so they can understand how people are moving around the community, reevaluating their zoning rules, and updating the master plan, all require money and resources. Osborne encouraged participants to make DOT and the other

________________

3 Infill refers to the development of unused or vacant land within existing developed urban areas.

agencies aware of barriers to progress. For example, she cited an administrative rule from the 1970s that multifamily housing could not be built on a former brownfield. Since then, methods for decontaminating brown-fields have advanced significantly, but the rule had not changed indicating a clear need to revise an outdated rule that was impeding progress.

Costs of HIAs

A participant raised a question about the costs, both financial and time, of conducting HIAs. Fulk responded that there are different levels of rigor for an HIA. The Green Street project (described previously by Florence Fulk on p. 15) is one of two HIAs that EPA is undertaking. The fact that EPA is involved means that these HIAs will be more elaborate, and will employ more resources, than what would typically be done, she said. The majority of the funding for these HIAs has gone toward bringing people together in community and stakeholder meetings and developing a document and the literature review to support it. In contrast, she described a rapid HIA to assess a prolonged heat policy that was completed in about 3 weeks by a work group for the Cincinnati Health Department. One of the goals for EPA is to level the playing field for all communities by providing freely accessible literature so they can better understand the relationships between the built and natural environments and public health, and Web-based tools and models to increase the rigor of community assessments. An HIA does not have to be an onerous, costly process, Fulk said.

Costs and Benefits

Roundtable co-chair David Kindig raised the issue of return on investment and the possibilities of achieving co-benefits in collaboration with other sectors, rather than each sector working on competing, marginal interventions. Ho explained that, according to the federal budget guidelines in the Deficit Reduction Act, a discretionary program that creates a cost offset in a mandatory program may not view the savings realized by the mandatory program as justification for investing in the discretionary program. In other words, she said, housing is not an entitlement, and there are rules that limit department options with regard to federal budgetary issues. For example, if housing provides a health impact and if, with Medicaid expansion, it has a significant federal dollar impact, it is not possible to work with the Office of Management and Budget or the Congressional Budget Office to justify an increased investment in housing based on a cost offset to Medicaid. In a state budget, however, these types of conversations can come into play. She noted that New

York and Ohio are considering the relationship between investments in housing and the potential for Medicaid savings. Elenberg recommended looking beyond return on investment to economic models that can assess the costs avoided, which are just as important as returns. Osborne said that DOT requires applicants to the TIGER program to conduct a full benefit-cost analysis on their project, specifically, whether the project can improve safety, economic competitiveness, livability, sustainability, and state of repair. Applicants are encouraged to look at and compare overall benefits and overall costs that often go well beyond the transportation sector. Elenberg noted that military installations are small communities in themselves, and some have asked for training on making such assessments (e.g., how to look cross-sectorally, what is the difference between an output and an outcome).

Livability in Rural and Urban Areas

In response to a question about expanding livability initiatives to rural areas, Osborne noted that there is often the perception that the elements of livability discussed only apply to urban areas. In fact, many of these elements (e.g., a town center where people can meet, a walkable community) originated in rural America, and it is a rural sense of community that these initiatives are trying to reintroduce to urban areas. That said, these initiatives could certainly apply to rural areas that need revitalization.

Communication

Roundtable member Sanne Magnan raised the issue of developing messaging that can appeal to both political parties and help to establish common ground on the importance of population health. Osborne said that many people like the concept of livability because it is good for the environment, for public health, and for access to opportunity, but the issue that resonates the most with federal policy makers is that it saves money. Fulk noted that the Office of Research and Development at EPA is focusing on helping people understand the beneficial link between human health and ecosystem goods and services. Elenberg stressed the importance of a good strategic communication campaign for helping to motivate people to participate in a public health initiative.

Leverage Points at Different Levels

Moderator Dawn Alley asked the panelists about approaches or leverage points to be considered at different levels of decision making. Osborne

noted that policies that will affect how the built environment affects day-to-day living in a community involve very localized decisions. At the state level, the governor can require coordination across departments, for example, coordination of public health and transportation initiatives. At the federal level, decision makers think more broadly. Elenberg observed that sometimes when the focus is on large changes, such as overhauling the food options available in a cafeteria, very simple interventions to foster health are overlooked, such as turning off the soda machines during breakfast hours.

Performance Measures

A participant asked whether the forthcoming federal MAP-214 performance measures consider transportation choice as a measure. Osborne responded that Congress prohibits DOT from defining any performance measure not specifically listed in MAP-21, but states are not limited in developing performance measures locally. Baltimore, for example, has accessibility performance measures that include distance between residential areas and public transit.

________________

4 Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21) is a long-term highway authorization providing funding for federal surface transportation programs. MAP-21 establishes national performance goals for federal highway programs. See http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/map21 (accessed March 10, 2014).