2

Benefit-Cost Analyses: Examples from the Field

Three speakers at the workshop provided compelling examples of the use of benefit-cost analyses to inform policy decisions. Though the examples are quite different, they reveal many of the issues that arise in gathering, analyzing, and disseminating benefit and cost data. They also demonstrate both the opportunities and the challenges of creating greater standardization in the field.

THE WASHINGTON STATE INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY1

In 1983 the Washington State legislature created the Washington State Institute for Public Policy to carry out practical, nonpartisan research at the direction of the legislature or the institute’s board of directors. A major activity of the institute is to conduct benefit-cost analyses of policy changes being considered by the state. As the institute’s director, Steve Aos, said at the workshop, the institute essentially functions as an investment advisor for the spending authority of government. It produces “buy and sell information” that legislators can use to make policy decisions.

The institute has looked at the benefits and costs of a very broad array of policies, including those affecting

• crime,

• education and early education,

• child abuse and neglect,

______________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Steve Aos, M.S., Washington State Institute for Public Policy, Olympia, Washington.

• substance abuse,

• mental health,

• health care,

• developmental disabilities,

• teen births,

• employment and workforce training,

• public assistance,

• public health, and

• housing.

The institute goes through a three-step process to determine benefits and costs. First, it examines what works to improve outcomes and what does not work. It applies a meta-analytic approach to all of the rigorous evaluations that it can identify of policies designed to improve public outcomes of legislative interest. It then combines studies that would be relevant to the state of Washington, a procedure Aos described as not only good science but good politics. Legislators can be suspicious of results based on a single study, he said, but if the results derive from every relevant study done in a particular field, those results have resonance.

Next, the institute examines the return on investment by computing the benefits, costs, and risks to the people of Washington State of a policy change (Lee et al., 2012). It uses a consistent framework to enable comparisons among options. This framework has developed over time, starting from a simple spreadsheet and evolving into a much more comprehensive evaluation.

Finally, the institute uses this information to help form budgets by exploring how a combination of options would affect statewide outcomes. This portfolio approach raises the analytic bar by considering such issues as diminishing returns when the beneficiaries of a policy are affected by multiple programs. All three steps are necessary, said Aos. In particular, the development of a portfolio of programs is just as much in need of standards as the evaluation of costs and benefits.

The product of this three-step process is a list of evidence-based policy options ranked by return on investment. The institute tries to present these in a Consumer Reports style, so the results look the same for a legislator working on K–12 education as for a legislator working on the juvenile justice system. Over the years, legislators have become accustomed to the format of the presentation and to being able to compare

across programs. “That has proven to be very fruitful across a wide number of areas,” Aos said.

The Nurse–Family Partnership as an Example

Aos looked in depth at the Nurse–Family Partnership program as an example of the institute’s approach. The costs of the program are derived from the costs of hiring nurses in Washington State labor markets, with the costs of instruction, service, and other activities included. Outcomes include reduced child welfare and victim costs, lower criminal justice costs, and savings in public assistance and health care. For example, the lower child welfare costs take into account the proportion of cases placed out of their homes and the marginal costs for foster care and other services provided to these youth.

Evaluations of the Nurse–Family Partnership program have found that educational attainment increases both for the children and mothers in the program, Aos stated. This increases K–12 costs as these individuals receive more schooling, including special education services. The reduced criminal justice costs are based on a detailed model that tracks every step from arrest through incarceration to community supervision upon release. According to the institute’s most recent results, the program produces a net benefit of almost $17,000 per family (see Table 2-1). The benefit to cost ratio is 2.73, and the return on investment is 8 percent.

Accounting for Uncertainty

Each of the estimated benefits and many of the costs have a standard error. The institute uses a Monte Carlo simulation with these errors to calculate the likelihood that a program will be beneficial in any individual case. For example, with the Nurse–Family Partnership, the net benefits are positive 76 percent of the time and negative 24 percent of the time. Though this is more risk that many people associate with the program, it still indicates the program is a solid investment, Aos observed.

TABLE 2-1 Return on Investment for the Nurse–Family Partnership in Washington State

|

Benefits per Family |

Main Source of Benefits |

|

|

Reduced child abuse and neglect |

$1,096 |

Lower CW & victim costs |

|

Increased ed. attainment (child & mother) |

$24,131 |

Increased earnings |

|

Reduced crime (child & mother) |

$5,333 |

Lower CJ & victim costs |

|

Increased K–12 costs |

–$1,738 |

Higher K–12 costs |

|

Other |

$2,854 |

Pub asst, health care $ |

|

Deadweight cost of program |

–$4,933 |

|

|

Total Benefits per Family |

$26,743 |

|

|

Cost per Family |

$9,788 |

|

|

Net Benefits (NPV) |

$16,956 |

= $2.73 B/C = 8% ROI |

NOTE: B/C = benefit/cost; CJ = criminal justice; CW = child welfare; NPV = net present value; ROI = return on investment.

SOURCE: Aos, 2013.

The analysis of the Nurse–Family Partnership program still could be improved, Aos said. He is eager to see more evaluations of the program, especially in situations comparable to those in Washington State and by evaluators who are not associated with the design or delivery of the program. Replications of programs may not be as effective as its initial implementation, which suggests that it may be necessary to discount results of evaluations done by a program’s developers.

Lessons Learned

Aos drew several broad conclusions from the experiences of the Washington State Institute for Public Policy. First, the results of benefit-cost analyses need to compare apples to apples, not apples to oranges. Aos tries to give legislators several options to meet a particular policy goal. So long as they are evaluated the same way, legislators can make decisions based on consistent evidence.

Second, results have to be understandable by all 147 members of the Washington State legislature—or, said Aos, at least by the committee chairs, the majority leader, and the ranking members. For that reason, methods need to be both intuitive and scientifically justifiable. Legislators also need to know about the uncertainty of results. If results cannot be explained in an understandable way to legislators, they might get published in a journal, but they will not affect policy.

Third, the institute’s results are calculated on an annual cash flow basis from three perspectives: that of taxpayers, that of participants in the program, and that of others who are affected by the program, such as the victims of crime. Different legislators can be interested in different aspects of the results, Aos pointed out, depending on whether they are on the fiscal committee, for instance, or the juvenile justice committee.

Fourth, the effect size of a program is important, but so is the risk associated with that estimate, said Aos. Legislators need to know about the uncertainty of results from benefit-cost analyses. Aos also warned against the tendency to double-count benefits. For example, some outcomes measure the same human capital construct, such as higher test scores and increased high school graduation. The institute uses trumping procedures to avoid constructs that end up measuring the same thing.

Fifth, because local conditions vary in the United States, the results of benefit-cost analyses will, too, indicated Aos. The same program that reduces crime in Texas will save more taxpayer money than it will in Washington State where fewer people go to prison. State-specific numbers are needed to reflect local conditions. In addition, results and methods need to be updated at least annually. These ongoing updates can incorporate new studies, model refinements, and better data.

Sixth, Aos recommended greater use of longitudinal research to estimate benefits and costs. For example, child abuse and neglect are linked to later outcomes such as a failure to graduate from high school or increases in crime. Longitudinal research using large datasets is now drawing these linkages, which need to be incorporated into the results of benefit-cost analyses.

Finally, Aos urged practitioners to borrow the best current thinking on the valuation of outcomes. In this way, work does not need to be redone, but it may need to be adapted to local circumstances.

The state budget in Washington State has been affected by the institute’s results, said Aos. As an example, he mentioned forecasts of the number of prison beds that will be needed in the state, which draw on

results from the institute (Aos et al., 2006). Uptake has been faster in some areas than others, but it is gratifying to be perceived as an honest broker and to supply information that makes a difference.

Communities That Care is a preventive intervention that takes a public health approach to promoting positive youth development and reducing problem behavior. As described by Margaret Kuklinski, Communities That Care relies on coalitions of diverse stakeholders, including mayors, police chiefs, teachers, and parents, who receive training and carry out Communities That Care in their communities. The intervention begins with a survey of the youth in a community to understand where risk factors are elevated and where protective factors are depressed. The coalition then selects and implements evidence-based prevention programs to reduce the most widespread elevated risks. The coalition monitors fidelity of implementation, assesses efficacy, and makes course corrections when needed to achieve the community’s overall prevention goals, with a coordinator overseeing these diverse activities.

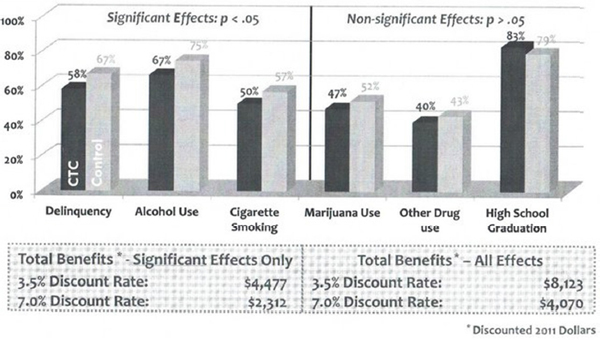

To determine the efficacy of the intervention, a randomized controlled trial was conducted involving 4,407 students in 24 communities and 7 states. The communities were matched in pairs within states and then randomized to condition, with no significant differences at baseline on important sociodemographic characteristics. Students were followed annually for 10 years, from fifth grade through age 19, with more than 90 percent of youth being followed over that period. Youth exposed to the program reported significantly lower rates of initiation community wide with respect to delinquency, alcohol use, and cigarette smoking, Kuklinski reported. Youth showed nonsignificant results for high school graduation, marijuana use, and other drug use initiation, but the observed changes were in the expected direction.

The program invested an average of $745,000, measured in discounted 2011 dollars, in each community over the course of 5 years in training, technical assistance, monitoring, preventive programs, and coordination. However, the costs varied across the 12 communities in the

______________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Margaret Kuklinski, Ph.D., University of Washington, Seattle.

study, Kuklinski observed, from $283 per youth to a high of $5,730 per youth, partly because of the differing sizes of the communities involved in the program and economies of scale in the implementation of Communities That Care. In deciding on a single estimate for the cost per youth, evaluators initially used an average cost of $1,159 as providing a conservative estimate. Later they determined that a weighted average of $556 per youth was a better estimate of the cost in communities in the sample as well as those likely to implement the program. They also used a range of 35 percent around that point estimate in Monte Carlo analyses to account for the variability in cost.

The Communities That Care program relied heavily on board members, volunteers, and teachers donating their time, which raises additional questions about how to value these nonbudgetary economic resources, Kuklinksi pointed out. One approach would be to assume that the time cost is fully offset by the benefits volunteers and teachers receive, in which case the net opportunity costs would be zero. A second approach is to value that time at the appropriate wage rate plus a fringe benefits rate for that position. A third option would value the time at the volunteer’s own wage rate plus a fringe benefits rate. The evaluators found the first and second options most compelling. This meant that the opportunity costs could range from zero to as high as an additional $89 per youth on top of the weighted average cost estimate.

In calculating benefits, Kuklinski continued, evaluators had to decide whether to monetize significant intervention effects only or all effects and what discount rate to apply to the benefits projections. If only significant effects were considered, the total benefits were $4,477 per youth at a discount rate of 3.5 percent (see Figure 2-1). At a 7 percent discount rate, the value was nearly halved to $2,312. If all effects were considered, the benefits were $8,123 and $4,070 at the respective discount rates, though the confidence intervals were greater around the point estimates when all benefits were considered.

Kuklinski showed that different viable assumptions lead to a range of conclusions. At the low end of assumptions, the benefit-cost ratio is 3.58, while at the high end of the assumptions, the ratio is 14.70 (see Table 2-2). In its analysis, the Social Development Research Group opted to include only significant effects, assumed no opportunity costs incurred for volunteers, and used a discount rate of 3.5 percent, arriving at a benefit-cost ratio of 8.22.

FIGURE 2-1 Including all effects or only significant effects and varying the discount rate have a substantial effect one the estimated benefits of the Communities That Care intervention.

SOURCE: Kuklinski, 2013.

Lessons Learned

Kuklinski drew several conclusions from the benefit-cost analysis conducted on Communities That Care. First, several important decisions have major implications for the bottom line of any such analysis. In the case of Communities That Care, the benefits included, the opportunity costs for volunteers, and the discount rate all had a substantial influence on the calculated benefit-cost ratio.

Standards for making some of these decisions would increase the value of findings in policy formation and improve comparability across studies, Kuklinski said. These standards could apply to research design, the assessment of costs, and the estimation of benefits. For example, in complex multisite trials where costs vary, the assessment of costs has implications for disseminating preventive interventions. Similarly, in some cases, it may be useful to specify different sets of outcomes to be included in benefit-cost evaluations within a specific program area. The logic models behind interventions can point to the important

TABLE 2-2 Different Viable Assumptions Lead to a Range of Benefit-Cost Ratios for the Communities That Care Intervention

| Range of Estimates* | SDRG Analysis |

||

| Low | High | ||

| Assumptions | Significant Effects, Opportunity Costs = $89, 7% Discount Rate | All Effects, Opportunity Costs = $0, 3.5% Discount Rate | Significant Effects, Opportunity Costs = $0, 3.5% Discount Rate |

| Benefits | $2,312 | $8,123 | $4,477 |

| Costs | (635) | (556) | (556) |

| Net Present Value | $1,667 | $7,617 | $3,920 |

| Benefit-Cost Ratio | 3.58 | 14.70 | 8.22 |

* Discounted 2011 dollars.

SOURCE: Kuklinsky, 2013.

outcomes to assess rather than focusing on the most broad set of outcomes to be monetized.

The field has not been clear about best practices, Kuklinski said, which raises the need for standards. Moreover, the need for standards has increased as the number of studies and applications has increased. The results of benefit-cost analyses can include many types of information, including internal rates of return, cash flows, investment risks, discount rates, and benefits and costs organized by various stakeholders. Adherence to best reporting practices may be needed for the users of information to have confidence in what they are reading.

A challenge for a future study of standardization in benefit-cost analyses would be to identify areas where common ground exists. For example, the appropriate discount rate, or a range of rates, may be an area where consensus could be achieved. Where consensus is less clear, the major alternatives need to be delineated. Greater standardization “would be of great use to researchers like me, to policy makers, and to practitioners who use this work,” Kuklinski said. “It would increase methodological consistency and help us be able to make meaningful comparisons of results from different studies.”

Charles Michalopoulos described several evaluations that MDRC has done of preventive interventions. First, the Minnesota Family Investment Program is a welfare-to-work program that provides work incentives to welfare recipients in Minnesota and a range of supports such as child care. Study of the program found that it increased employment and income among participants. At the same time, evaluators found that the program had benefits for children whose parents were in the program. In particular, children’s academic achievement rose, especially among young children. The program cost the government about $2,000 per participant per year. However, the evaluations did not monetize all of the benefits, such as improvements in child well-being, increases in the rate of marriage among program participants, and distributional effects. Also, the analysis did not present a measure of uncertainty.

A second example is a study of the Foundations of Learning program, which is an intervention to help Head Start teachers in their classroom management and to provide classroom mental health consultants. Results suggested that the program improved teachers’ ability to manage their classrooms and reduced problem behavior, but it did not have other benefits for children once they entered school. In particular, it did not increase their mathematics and reading skills. The costs of the program were $1,750 per child, but the benefits, such as reduced problem behavior, could not be easily monetized. In contrast, a goal such as avoiding special education, which is quite expensive, could be monetized, Michalopoulos observed.

Michalopoulos also discussed evaluations of programs based on the Nurse–Family Partnership model. Three randomized controlled trials of programs found savings in health care, welfare, and criminal justice costs. The Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy recently declared that the Nurse–Family Partnership program is in the first tier for being an effective program. The success of this program had a substantial effect on the Affordable Care Act, which allocated $1.5 billion for implementing and studying home visiting programs. The program also is currently reimbursed through some state Medicaid programs.

______________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Charles Michalopoulos, Ph.D., MDRC, Oakland, California.

Lessons Learned

Experience with these and other programs illustrates several challenges related to measuring costs, Michalopoulos said. First, one-time costs, such as teacher training in the Foundations of Learning program, can be problematic. Once teachers were trained, they could keep benefiting children as long as they stay in their jobs. Should the initial costs be spread over a period of time? This is an area where standards for benefit-cost analyses would be useful.

A related question relates to the differences between demonstration programs and ongoing programs. Again, with the Foundations of Learning project, teachers already undergo training in the course of their work. If new training could be added to existing training, the costs of administering the program would be reduced.

Many benefit-cost analyses do not devote enough effort to express statistical uncertainties about the results, Michalopoulos said. In a study of benefit-cost analyses for early childhood interventions, Karoly (2012) found only three studies that expressed statistical uncertainty. However, large uncertainties may lead to different policy implications than would small uncertainties.

Michalopoulos also made the point that significance tests are often the wrong choice for making policy decisions. For example, an intervention with an average net benefit of $400 and a standard error of $200 would be statistically significant, but if the standard error were $300, it would not be significant. Yet the second intervention would still have a 91 percent chance of saving money. In addition, an outcome that is not statistically significant can be substantially more important than an outcome with an equal confidence interval. A better measure than statistical significance, said Michalopoulos, would be whether an intervention is likely to save money or meet some other objective.

Including results that are not statistically significant points to the advantages of designing a benefit-cost analysis ahead of time rather than looking at the results of an analysis and deciding which to include in an analysis, Michalopoulos pointed out. However, it may be necessary to omit measures that have large amounts of uncertainty. For example, projections 20 years into the future may be too uncertain to include in a study. Adding a benefit with great uncertainty to more certain benefits may create too much uncertainty for the overall measure of benefits,

reducing the value of a study. Also, some outcomes may be too difficult to monetize, even if they seem important.

These kinds of decisions can be difficult to make Michalopoulos admitted. For example, outcomes that occur in the near term are often more certain than long-term outcomes. As another example, the indirect effects of an intervention on peers of siblings may be important but hard to measure. MDRC studies typically focus on outcomes that are relatively certain while pointing to other factors that may make outcomes better or worse.

Long-term follow-up can reduce uncertainties in benefit-cost analyses, Michalopoulos observed. However, the question has to be asked whether outcomes observed in one context and with one group can be generalized to other contexts or groups. One way to answer this question is simply to assume the benefits will be lower in a different setting; but how much lower? Multisite and multisubgroup studies can help answer these questions, but results may change with the assumptions made. Also, circumstances can change over the course of an extended study and increase uncertainty in overall outcomes. Focusing on a few outcomes with greater certainty can be supplemented by longer-term projections.

Michalopoulos urged against developing standards that exclude good research or codify bad research. For that reason, establishing guidance or principles may be a better approach than defining standards. He also called attention to two areas of tension: the contrast between the complexity of benefit-cost analyses and the simple answers policy makers want and need, and the need to focus on key outcomes while still measuring everything of importance.

The diversity of outcomes from most interventions emphasizes the need to focus on key outcomes that can be monetized with reasonable certainty, Michalopoulos concluded. Many relevant benefits can be measured, but which benefits to monetize remains an important question. For example, the target age of a child may be less important than whether the benefits are monetizable. Also, the intended uses of information can affect the outcomes being measured. For example, a department of health may be more worried about child health outcomes while a department of human services is more worried about cognitive development. However, in comparing programs with similar goals, application of the same standards would be very useful.