3

Assessing the Costs and Benefits of Interventions

At the heart of conducting a benefit-cost analysis is assessment of the benefits and costs of an intervention. Both of these dimensions are challenging, but could benefit from greater standardization in the field. Two speakers at the workshop looked specifically at the costing of interventions, while one explored the valuing of benefits.

AN INGREDIENTS APPROACH TO COSTING PREVENTIVE INTERVENTIONS1

Benefit-cost analyses tend to use calipers to measure effects and witching rods to measure costs, said Henry Levin. In many cases, costs are all but ignored because analysts are so focused on finding effectiveness results. This includes not just overt cost transactions but other costs that together represent the true costs of an intervention. For example, a budget is not necessarily a full or accurate metric for determining costs, Levin observed. Nor do administered prices in a hospital or grant support for a community intervention provide accurate pictures of the resources required to produce benefits.

In determining costs, important questions include

• What are the criteria for determining costs?

• How complete are the costs? Do they cover all of the requirements needed to produce the effects on which benefits are based?

___________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Henry Levin, Ph.D., Columbia University, New York, New York.

• Do the costs use comparable prices for comparison (e.g., local versus national prices for goods and services can vary dramatically in price)?

• Is the information adequate for an observer to replicate results?

Standards for benefit-cost analyses will not be easy to develop, Levin acknowledged, but they may help answer these questions.

The Ingredients Cost Method

Levin uses what he called the “ingredients cost method” to determine costs. It relies on the use of competitive market prices or shadow prices based on markets. Its goal is to ascertain the cost of all the resources required to replicate an effectiveness result.

The method has several major steps. First, for each alternative, an intervention and its theory of action need to be described. This enables a benefit-cost analysis to reflect what was being attempted and how and why outcomes occurred.

Second, the specific ingredients or resources used to implement the intervention need to be described in terms of both quantity and quality, irrespective of how they are financed, Levin said. A volunteer can be self-financed, but a volunteer is not simply free, because in another setting the market cost for that input must be paid. Documents, interviews, and observations can identify these ingredients or resources, although these sources of information may not be fully available for interventions conducted in the past.

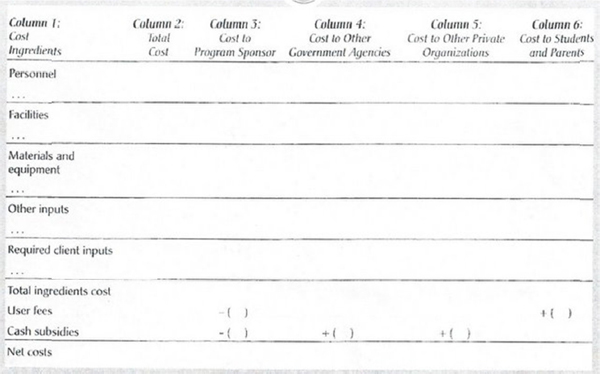

Third, market or shadow prices are assigned to all ingredients based on opportunity costs. This is done independently of funding sources, including in-kind resources such as volunteers. Finally, the costs are analyzed in different ways to make them amenable for analysis and comparison. For example, marginal costs or average costs may be calculated. These costs can be presented in the form of worksheets that identify the categories of program ingredients and the constituencies who are paying for those ingredients (see Figure 3-1). Developed during the past four decades, this method has been computerized and includes a database of prices, discount rates, and other data, Levin said. For example, the Poverty Action Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has adopted this method to do cost-effectiveness studies of its randomized controlled trials.

FIGURE 3-1 Worksheet identifies types of costs and the groups on which costs are imposed.

SOURCE: Levin, 1975. Reprinted with the permission of Sage Publications.

Levin particularly pointed out that the identification of costs needs to be done separately from a program’s financing. For example, over time, a program may not be able to sustain volunteer efforts, in which case it may be necessary to look for financing to cover those costs. Separating financing from costs is a bedrock principle of cost accounting.

Levin also pointed out that doing a cost analysis can sensitize people to the assumptions made in that analysis, just as with analyses of benefits. For example, a question that can arise is what does the time and effort that a student is putting into a program displace? That is not an easy question to answer. Some interventions may argue that they cost nothing or very little, but the ingredients cost method demonstrates that their cost may be fairly high. For example, some interventions simply reallocate resources from one program to another (e.g., from health prevention to educational enrichment) and argue that there is no cost. Of course, the cost is determined by the value of what is sacrificed by abandoning the initial program rather than assuming that such transfer is “free.” Figuring out what these opportunity costs are is important, said Levin.

A Call for a Civil Union

Levin urged setting standards for cost analysis that are equally rigorous as those for both effectiveness and benefits analysis. Costing should not be an afterthought, he said, but should be closely related to and done simultaneously with benefits analysis, with the sharing of data for a complete evaluation.

Analyses also need to incorporate a strong ethnographic component that documents the intervention process and ingredients, Levin added. Such analyses, which could be done parsimoniously with periodic visits and data gathering, can reveal what really happened during an intervention, not just what theory would predict should happen. Qualitative analyses also can help explain differences in site results.

Finally, retrospective cost analysis should be avoided, Levin said. Though sometimes necessary because costs were ignored at the time of the intervention, such analyses irretrievably lose much information. If done retrospectively, it is important for cost analyses to be as timely as possible.

COST ANALYSIS FOR PLANNING PURPOSES2

Whether with expanded home-visiting programs, school violence prevention efforts, or early learning initiatives, robust cost estimates are needed to support prevention efforts that can effectively meet public health needs and reduce the strain on overburdened service systems, said Max Crowley. In particular, by demonstrating the resources needed for prevention, cost analyses are inextricably linked to efforts to take interventions to scale. “Even basic cost estimates can end up having greater utility for program planning than some of our best estimates of program cost-effectiveness or benefit-cost ratios,” Crowley said.

Crowley discussed three key issues related to the process of costing prevention programs. The first involves the resources needed to ensure adequate programming infrastructure is in place. Many estimates of prevention costs capture only the most immediate resource needs of programs. In particular, they often neglect crucial elements of infrastructure.

___________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Max Crowley, Ph.D., Duke University, Raleigh, North Carolina.

For example, local knowledge about how to adopt and implement preventive programs can vary tremendously on the ground. Many programs now use manualized training to teach program facilitators how to deliver a specific prevention curriculum, but few programs seek to train the managers overseeing those facilitators to ensure programs are delivered as they were intended and with quality. Nor are these managers generally taught how to enable themselves to fend off threats to the sustainability of a prevention effort, even though such training is often crucial to replicating the effects of an evaluation trial. These skills are often assumed to be available in the existing labor market, but the reality is that these skills may be in very short supply, especially in rural or impoverished areas. To successfully deliver preventive programs and replicate the effectiveness of trials, this local capacity must be deliberately built through training and technical assistance, Crowley said, which can require significant resources. “If we don’t budget for infrastructure, we can undermine the whole prevention effort.”

Infrastructure building can be divided into three main areas: adoption capacity, implementation capacity, and sustainability capacity. Adoption capacity refers to the ability of a local community to attract or train a labor force with the ability to adopt an evidence-based prevention program. This involves local capacity to understand the needs of the target population as well as the fit of a program in that community (Lutenbacher et al., 2002). Prevention delivery and support systems such as the PROSPER (PROmoting School–community–university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience) Network and Communities That Care (see Chapter 2) seek to supplement this local capacity when it is lacking. These systems also allow for different programs to be deployed depending on local needs. Such “plug and play” systems allow program evaluators to include infrastructure development in their cost analyses with less research burden than if a program were implemented in isolation.

Implementation capacity refers to the ability to deliver the program from manualized curricula and to ensure program quality. Many communities lack existing quality assurance systems that are compatible with many of the prevention programs currently available in the marketplace. Developing these systems can take time, but they are essential to ensure prevention services are delivered with fidelity (Durlak and DuPre, 2008).

Sustainability capacity refers to the ability of a prevention effort to integrate a program into the existing service infrastructure and develop robust funding streams. Developing this capacity requires training and

ongoing technical assistance around fundraising and management of in-kind and volunteer resources.

Volunteer and In-Kind Donations

The next issue Crowley discussed involves volunteer and in-kind donations. Because they attempt to avert a future outcome, prevention programs often require substantially greater buy-in than do downstream solutions that seek to triage existing and visible problems (Elliott and Mihalic, 2004). As a result, prevention initiatives often rely heavily on local volunteer and in-kind donations. Securing these resources not only solidifies buy-in from the community but also can help alleviate resource scarcity (Feinberg et al., 2008).

Program evaluators often seek to estimate the cost of a program retrospectively (Crowley et al., 2012). But institutional knowledge of what group donated which resources and which people volunteered their time is often lost in such analyses. This is particularly a threat for programs that rely on existing service infrastructures to house their programming. While there will always be a place for retrospective analyses, Crowley acknowledged, the issue is planning for cost analyses up front in a project. By building an overall data architecture, costs can be captured in more naturalistic settings so the process is less burdensome.

As an example, Crowley noted that the education system has often been the natural home for preventive interventions targeting adolescent populations. The opportunity costs of such a program may be small when they are delivered within trials, but when they are delivered at scale, they often require sizable investments from local education systems. These investments include not only the more visible teacher time but also the less visible administrative and staff time. When these costs are not captured, they can threaten program planning and place an unexpected burden on service systems, possibly derailing an entire program.

Participant Costs

When prevention programs seek parental support, as is often the case with family-based programs, this support represents a cost, Crowley pointed out. Parents are also the targets of many preventive programs.

Thus, participant costs can include the cost to a child, the cost to a parent, and the cost to a family.

Participant costs require special handling, Crowley observed. Sometimes costs are incurred up front, often through losses in time, but sometimes they are incurred as part of programs themselves. For instance, preventive programs that improve parents’ success in the labor market can produce a cost to children. The hope is that child participants will gain an overall benefit from the program. But the cost to a parent of not being able to provide child care can be important for recruitment and participation in a program and can inform program planning.

Self-report interviews can identify losses of service, but they can fail to capture the complexity of program costs, especially in the context of increasingly dynamic preventive efforts that are delivered across substantial periods of time. However, with the development of more robust data collection systems, particularly through new technological supports, the field can dramatically extend the science around prevention costs, Crowley observed. For example, the geographic information systems being deployed by many community prevention efforts can capture such costs as participant travel time to participate in a family-based program. Looking farther into the future, e-health technologies could collect large quantities of data to quantify participant costs.

Potential Best Practices

Crowley concluded by pointing to several best practices that can guide the development of standards for cost analyses. First, he said, cost analysis should always be prospective. Failing to include a cost analysis at the beginning of a trial makes the process of estimating costs much more difficult and increases the likelihood that cost estimates will be incomplete. Ideally, funders and reviewers will someday expect a program evaluation to include capturing opportunity costs.

Another best practice, Crowley observed is to use the ingredients-based approach described earlier by Levin to capture a full economic accounting of a program and deconstruct the resource needs into specific cost categories. Such an approach would yield more standardized protocols for cost collection and would link resource consumption to program activities.

Third, cost analyses should always seek to estimate the full economic costs of implementing the program, Crowley said. Cost estimates need to move beyond simple budgetary review and include all of the resources needed to replicate a program’s effects. These resources include those needed to build local capacity, the cost of donating time and goods, and a full accounting of participant costs.

Fourth, Crowley pointed to the need to explore uncertainties in cost estimates. Sensitivity analyses could test the robustness of cost estimates under a variety of assumptions. Monte Carlo analyses can be applied to the costs of a program as well as to the benefits to yield confidence intervals around point estimates.

Crowley also identified four areas that could benefit from greater standardization:

1. Identify essential cost categories that all cost analyses should strive to include.

2. Develop guidelines for appropriate handling of costs that are not reflected in program budgets.

3. Establish minimum levels of sensitivity analysis to explore uncertainty in cost estimates.

4. Ensure consistent reporting of cost estimates to enhance transparency and utility.

Prevention programs, especially for children, youth, and families, are increasingly in the spotlight, Crowley observed. Well-done cost analyses can describe these investments and help communities decide which investments to make. But cost estimates need to capture all of the resources needed for a program to avoid jeopardizing the quality of the services being delivered and the sustainability of a program.

VALUING THE OUTCOMES OF INTERVENTION3

When a preventive intervention is evaluated, the headline is often the total economic return the program will generate. But this headline

___________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Damon Jones, Ph.D., The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania.

obscures a number of important questions about what is included in the total dollar amount, said Damon Jones, including

• Is the return based mostly on one sector?

• Does it involve a combination of many sectors?

• Who is receiving the economic benefits—participants, taxpayers, other nonparticipants?

• When does the savings or benefit occur?

• Is the benefit based on projections?

These are the kinds of questions that need to be addressed to measure the economic outcomes of an intervention, Jones stated.

Previous benefit-cost analyses of early childhood interventions have found benefits in a variety of economic and societal sectors. For example, evaluations of the Perry Preschool Project have found lower crime rates, less retention and special education use in school, and increased lifetime earnings (Belfield et al., 2006). Study of the Chicago Child Parent Centers revealed increased earning and tax revenues, reduced costs associated with crime, and reduced need for special education services (Reynolds et al., 2011). The Abecedarian Program demonstrated increased lifetime earnings for participants, increased maternal earnings, decreased school costs, and decreased smoking-related costs (Barnett and Masse, 2007).

An important question with these and other studies is how these outcomes were monetized, said Jones. For example, shadow prices for valuing interventions are often a critical element of this process. Shadow prices evaluate the return on such interventions as increasing high school graduation or test scores or reducing criminal acts or early substance use. Shadow prices are harder to determine for outcomes measured at younger ages, Jones observed. Shadow prices also are easier to apply with some sort of categorical result, such as a diagnosis. And the more projection required to determine a price, the more uncertainty needs to be accounted for in the methodology.

Standards for Valuing Benefits

Currently there are no established standards for valuing benefits, Jones noted, especially with preventive interventions in the behavioral

sciences. Instead, economic evaluations are carried out in widely varying ways with respect to approach, measures, outcomes, and the structure of the assessment. In thinking about how to monetize benefits, a decision has to be made between determining how to value key study outcomes that may be indirectly linked to dollar amounts and focusing on the extent to which a program affects true economic outcomes. The answer to this question depends largely on the nature of the program, the age of the participants, and the outcomes that are targeted. Studies of preventive programs for children and families, for example, vary widely in terms of what outcomes are monetized. Many outcomes are left out because of a lack of precedence for how to monetize them, such as mental health outcomes, social skills, child behavior, and parenting skills.

Great variation also surrounds how effects are projected into the future. Some studies look only at the low-hanging fruit, which may lead to greatly underestimating economic impacts. But the difficulties involved in measuring the harder-to-obtain outcomes can lead to errors in estimates. At the same time, evaluators need to consider the full set of possible outcomes (both observable and those projected to occur) to achieve adequate coverage of economic impact.

A critical step for any evaluation is to think about what is left out, Jones added. When interventions are evaluated for economic impact retrospectively, the lack of planned measures may lead to incomplete assessment of benefits. But this could also be partly a matter of the inability to capture costs within a set of measured outcomes.

What may be particularly underestimated is the value of factors linked to long-term personal success, such as the development of interpersonal and intrapersonal skills, said Jones. The complexity of the interrelationship among different factors—such as cognitive and noncognitive skills, as well as context of these factors—is not easily represented in assessments of economic benefits. Even when the importance of certain skills for long-term personal success is recognized, the challenge is determining how to capture those skills in measuring outcomes that are not currently included. Possible approaches can build on prior research, but a standard methodology for modeling more complex associations is unlikely.

Valuing Outcomes

Although there are no clear standards for carrying out economic evaluation in preventive interventions, certain steps could be taken to increase consistency across studies. For instance, the first step in developing standards for valuing outcomes is to plan ahead, said Jones. As with the evaluation of costs, the economic evaluation component needs to be considered before establishing plans for the overall program evaluation, he observed. This requires consulting with economists who can provide expertise on how to structure an evaluation. It also requires reviewing prior research to learn what has been done, with what population, and in what context, and also checking whether any standards already have been established for economic evaluation.

The second step is to consider the scope and reach of a program’s effects. What outcome domains will be affected? How far over time will these effects extend? Who will be affected? These questions reflect the logic model of the intervention, and while it is possible to include too many different effects, more is preferable to less, Jones said.

The third step is to determine the best measures for economic evaluation based on the intervention’s logic model, Jones continued. Measurable outcomes as well as program benefits that cannot be measured need to be identified. Prior research may have used measures that can be applied or used in models. Deciding how to represent the uncertainty in valuations is also part of this step.

The fourth step in the process is to assess what key program outcomes cannot be valued, Jones said. Evaluators then need to determine whether the evaluation should incorporate other methodologies to determine economic benefits for these outcomes. If the outcome is a primary variable in the program evaluation, should the evaluation incorporate a cost-effectiveness component? Current or future research may help determine the possible valuation of these outcomes so they can be incorporated into later retrospective assessments.

Examples of the Approach

As an example of identifying potential outcomes, Jones described a hypothetical middle school preventive intervention program aimed at improving social skills and decreasing substance use in adolescents. The

program was delivered in the sixth grade through a curriculum occurring 2 days per week. It involved components such as demonstrative video modules, journal writing, and role-playing activities. A pilot study indicated multiple program effects measured at posttest, including fewer class disruptions, lower rates of bullying, increased engagement in class, and lower rates of initiation of substance use.

In subsequent research the evaluators wanted to include an assessment of the program’s economic impact, Jones continued. They planned to assess the full cost and resources needed to deliver the program. They also planned to follow participants into high school to assess longer-term effects of the program. Prior research provided common methods for valuing outcomes in school programs, which helped the researchers determine what measures to include for this age group at posttest and follow-up assessment. These measures included use of special education services, class grades, grade retention, reported substance use, and use of other school services (including disciplinary and counseling services).

For a middle school program, participants can provide outcomes that are more readily monetized than for other populations or programs, Jones said. For instance, academic achievement can be identified at these ages and followed through high school. Moreover, substance use, delinquency, and early involvement in the justice system all can be measured.

Still, Jones observed, several key questions need to be answered. Are only the outcomes listed above valued, some of which also involve direct costs? How much can the costs from effects on current outcomes be projected into the future? For example, should reduced early substance use be projected to reduced longer-term problems? Should improved academic achievement be projected to future earnings? How about the value of outcomes that are not easily monetized? How long should effects be followed? For example, if participants are followed into young adulthood, should things like high school completion, college experience, early employment, longer-term substance use patterns, and longer-term delinquency and criminal activity be assessed? Evaluators also need to assess whom else might be affected by a program, such as teachers, other educators, family members, or the broader society.

The effects of a program can be distinguished by recipient, time frame, and whether they can be monetized. These potential outcomes can be derived from the logic model for a program, Jones stated, including both effects that can be monetized and those that cannot.

Programs for Younger Children

Some programs are at a disadvantage for economic evaluation based on the nature of the processes involved, Jones said. For example, younger children usually cannot be followed much beyond the time frame of program delivery, and outcomes measured at young ages usually cannot be readily monetized. In addition, intervention effects linked to future costs are typically subject to down-weighting through discounting and fade-out.

At the same time, lasting effects may rely on delivering services to children during key developmental periods, and research has demonstrated the importance of early intervention (Cunha and Heckman, 2008; Dodge et al., 2008; Barnett, 2011). The challenge is how to value outcomes with complex processes involving multiple dynamic and interacting factors. For example, important new research is examining the mechanisms by which noncognitive factors and personality influence long-term success (Almlund et al., 2011). Ideally, this research could help explain how these factors collectively influence future adult outcomes and how they are best measured in economic evaluations. For example, noncognitive factors could be more important at older ages and more malleable, making them a better candidate for intervention with older children. Today, however, Jones indicated that the role of noncognitive skills on long-term success is not represented in economic evaluations of programs for children.

The Potential of Research

The field will be greatly helped by research that establishes the links between outcomes in program evaluations and future direct or indirect costs and benefits. This research should be based on robust methodology, include multiple studies, and involve causal associations, Jones said. Once those links are determined, then some consensus is likely to develop as to what measures best represent early skills. If certain domains, such as early aggression or social skills, are found to have a stronger association with economic outcomes controlling for other factors, these areas could be prioritized. Research also could factor in how much these traits may fluctuate over time, the likelihood that they may change as the chronological gap between measured skill and economic outcome is increased, the influence

of different contexts for understanding these associations, and the varying characteristics of different populations.

Variable associations may be represented in terms of likelihoods for later states to occur. For example, an improvement in an early mental health outcome may increase the likelihood for high school completion. Around this likelihood, the potential for variation in causal influence must be understood. In this context, ranges of estimates are good. Policy makers may not like ranges, but they need to be factored into the overall sensitivity analysis of the economic evaluation.

“The future is bright,” Jones concluded. Economic evaluations for family, child, and youth programs will only get better in the coming years. But standards and consistent methodologies are needed to compare across studies, Jones stated, and researchers need to fully consider the possible impacts of effective programs. Thus, some collective organization of determining and promoting appropriate methods and measures would help researchers in the future.