4

Issues to Consider in Benefit-Cost Analysis

Two sessions at the workshop focused on several of the prominent methodological issues that arise when evaluating preventive interventions. Those presentations are combined in this chapter to explore in greater depth some of the questions that will have to be addressed in developing standards for benefit-cost analyses. During the course of the discussion, a topic that received special attention from several presenters was the kinds of research designs that can generate valid evidence.

IDENTIFYING CAUSAL ESTIMATES BY RESEARCH DESIGN1

Randomized controlled trials are not always possible to conduct when evaluating preventive interventions. In those cases, different experimental designs must be pursued for generating causal knowledge, including regression discontinuity analyses, interrupted time series designs, nonequivalent control group designs, and single case design. Thomas Cook explored the potential of several research designs that can be employed in benefit-cost analyses.

He began by looking at the within-study comparison method, which in the past has often produced results very close to those of randomized controlled trials. In one form, an overall population is selected into a randomized experiment group and a comparison group. The randomized experiment group is then randomly assigned to a control group and a treatment group, yielding a randomized controlled trial. The nonequivalent comparison groups are formed by systematic assignment into the same treatment

___________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Thomas Cook, Ph.D., Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

and control statuses, with individuals most often self-selecting into the treatment or control status or being so appointed by an administrator. An effect size can be calculated for the observational study and compared with the effect size from the randomized experiment.

In the second form, a within-study comparison involves taking a randomized experiment, calculating its effect size and then contrasting a nonequivalent comparison group by self-selection or administrator selection, Cook continued. This nonequivalent comparison group is then linked to the same treatment groups as in the randomized experiment, and an adjusted effect size is created after trying to control for any selection differences between the treatment and nonequivalent comparison group. Then, the effect sizes from the experiment and nonexperiment are compared. If they are similar, the conclusion is drawn that the nonexperimental results were not biased. If they are different, the opposite conclusion is drawn.

Whatever within-study comparison method is chosen, an important goal is to identify the conditions under which a given observational method produces better or worse approximations to the causal estimates from a randomized controlled trial. For example, seven within-study comparisons comparing randomized controlled trials with regression discontinuity studies have produced similar causal estimates at the cutoff, Cook said. Though this is theoretically trivial, since regression discontinuity studies are supposed to produce this result, it is encouraging that the same cutoff-specific results were achieved as in the randomized controlled trials since this indicates that the implementation of the regression discontinuity studies did not produce bias. More important is the one relevant study comparing experimental results to those from a comparative regression discontinuity study that includes pretest values along all the assignment variable and so can serve to index the functional form relating the assignment variable to the outcome without treatment. This one study showed the same results as a randomized controlled trial in all areas away from the cutoff, and not just at it as in the simpler regression discontinuity design with only posttest data (Cook et al., 2008).

In addition, seven studies have compared randomized controlled trials with interrupted time series studies, all but one of which used a comparative interrupted time series with a nonequivalent control group time series. As Cook observed, all showed the same results for treatment-caused changes in the mean and, where tested, for changes in slope also.

Nonequivalent control group designs are more common than regression discontinuity or interrupted time series in actual research practice.

More than 20 within-study comparison studies of such designs exist in many different fields, though they are skewed toward job training and education reform. They show close approximation of randomized controlled trial results when the comparison groups are very local, when pretest measures of outcomes are used to match groups, when there is independent knowledge of all or most of the selection process, and when there is multilevel matching. It also works when there is a hybrid matching strategy that combines local matching where it works well with nonlocal focal matching wherever local matching does not work. These procedures can reduce all bias sometimes and some bias almost always, said Cook. However, none can be guaranteed to reduce all bias all the time. In the future, this line of research will continue to seek a combination of various strategies to improve predictions when randomized controlled trials results are stably, but not invariably, replicated.

Experimental Designs and Clearinghouses

Today, several clearinghouses exist, including the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) (http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc), the Campbell Collaboration (http://www.campbellcollaboration.org), and Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development (http://www.blueprintsprograms.com). Cook limited his remarks to the WWC, but other speakers, as described later in this chapter, spoke more broadly about the stamp-of-approval mechanisms applied by these organizations.

The WWC’s standards for regression discontinuity studies are now being revised, Cook noted, but the currently proposed revisions do not deal with the advantages of comparative discontinuity studies, which “seems odd.” However, steps are being taken to add consideration of such designs as the new standards are worked out. In addition, the WWC does not include interrupted time series or comparative interrupted time series except in single case designs, which seems “short-sighted given the evidence to date,” according to Cook.

Today, the WWC accepts nonequivalent control group designs only if the treatment and control groups do not vary at pretest on measures of the outcome. But this is “naïve,” said Cook, because it does not consider time-varying pretest mean differences by group and because some de-

signs without pretest measures of the outcome still use sophisticated matching techniques. More sophisticated consideration could be given to the WWC standards for accepting nonequivalent control groups as acceptable. However, Cook concluded by agreeing with almost all that is in the WWC, and he generally endorsed its standards. At issue for him are extensions to the current standards more than replacement. In particular, greater consideration could be given to the special status of comparative regression discontinuity studies and to comparative interrupted time series designs into the clearinghouse.

Results also would benefit by an external warrant, said Cook, so they are not the product of an individual researcher’s choice or preferences. Current statistical theory cannot provide this warrant because it cannot specify those features of a given application that meet its assumptions. So when an experiment is not possible, “satisficing” standards could meet a threshold of acceptability. Within-study comparisons seek to generate an empirical warrant for meeting a “satisfying” criterion. Any imperfect design is satisfying if it often produces the same results as a randomized experiment on the same topic.

DESIGNING ERROR-TOLERANT STUDIES2

Sometimes policy makers use the results of benefit-cost analyses well, but in many cases research fails to translate into socially beneficial action, said Jens Ludwig. Part of the problem is the limited scientific literacy of the users of research. It is very difficult to explain to nonspecialists the difference between failing to reject the null hypothesis and accepting the null hypothesis or the difference between a good design and a bad design within a class of research. Furthermore, as Ludwig has learned from living in Chicago, “Politics turns out to be very political.”

As an example of the difficulties encountered when disseminating the results of research, Ludwig pointed to the National Head Start Impact Study, which looked at the impact of Head Start on children at the end of first grade. Magazine reporters and think tank commentators used the results to conclude that Head Start does not work or delivers broken promises (Besharov, 2005; Barnett and Haskins, 2010; Klein, 2011). In

___________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Jens Ludwig, University of Chicago, Illinois.

fact, the results showed positive results in letter identification, spelling, vocabulary, and oral comprehension, but the confidence intervals were wide enough that two of the four results included the possibility of zero. Because the confidence intervals included both effects that were large enough for the Head Start analysis to pass a benefit-cost test, but also included zero, in the final analysis the impact study simply was not able to determine whether Head Start would pass a benefit-cost analysis. Ludwig said that this was a case of misunderstanding basic statistics.

One way to reduce misinterpretations of research results would be to educate the consumers of results. But if even think tank commentators misunderstand such results, said Ludwig, large-scale consumer education seems implausible.

Research Geared Toward the Research Consumer

Researchers need to anticipate the difficulty policy makers and consumers of research have in using research results in socially productive ways, Ludwig said. In fact, according to Ludwig it is very difficult for research consumers to distinguish between good and bad studies even within a given research design. Moreover, it is not all that clear that the existing “stamp of approval” mechanisms are helpful in guiding research consumers. One approach that the research field may consider in order to aid research consumers is to adopt an alternative system that simplifies the process of determining the difference between the good and bad studies by using a high-quality study design bar, which includes fewer classes of research designs. The trade-off for this approach is excluding some good studies that may fall short of the quality bar that is set for research designs. Some suggestions Ludwig made about what researchers can engage in to assist research consumers are mentioned below.

First, researchers should not conduct underpowered experiments, Ludwig said. In particular, their experiments should have adequate power to tell whether an intervention passes a benefit-cost test. Second, research should be reported in a way that the consumers of research are able to adjudicate between a good and bad study within a given research design class. One way for the research field to enable such judgments is through a stamp-of-approval mechanism. Today, several such mechanisms exist, Ludwig observed, including the WWC. At the moment, however, none of the existing mechanisms does exactly what is needed

to aid the consumer of research. These systems could be studied to determine whether they are constraining claims about evidence in ways that are helpful or unhelpful, though this determination is likely to differ from one policy area to another. An interesting question is whether all stamp-of-approval mechanisms could cohere on a given standard and whether that would solve the problem.

Ludwig stated that research consumers like having mixed results within a class of research designs. For instance, if policy makers or advocacy organizations know what they want the answer to be, they can look at a broad class of research studies to find the results that meet their expectations. Perhaps one way to solve this problem, said Ludwig, is to establish tight standards for research design quality.

One approach could be to include as evidence only the results of randomized controlled trials or regression discontinuity studies. A limitation to this approach, admitted Ludwig, is that such a decision would throw away good information from other kinds of studies. Another approach would be to develop a checklist that studies must satisfy. For public debates, the idea that some sort of checklist is going to constrain the kind of evidentiary claims that are made is probably not realistic.

Focusing on the errors made by the users of research results could yield important advances, Ludwig concluded. A useful step may be to do retrospective reports of how benefit-cost analyses are used, and abused, in the real world to identify problems that then could be mitigated. This could perhaps guide the field in how to move forward.

DECIDING WHAT EVIDENCE TO INCLUDE3

Rebecca Maynard discussed four key considerations surrounding what evidence to include in benefit-cost analyses: (1) overall relevance of the study, (2) relevance of the impact estimates that are reported, (3) causal validity of the impact estimates, and (4) adequacy of reporting.

___________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Rebecca Maynard, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Overall Relevance of the Study

The first question is whether the intervention is relevant to the policy or practice decisions under consideration, said Maynard. Studies may address important interventions, but those studies may not be relevant in a particular setting or at a particular time. In a health intervention, for example, a set of medications or foodstuffs that need refrigeration have little or no relevance in areas where refrigeration is not available.

Another question regarding the overall relevance of a study is what an intervention is being compared with. For example, a social and emotional behavior program is going to have quite different effects in a functioning family than in a family in chaos. Knowing the counterfactual is important in judging whether or not a given set of impact estimates is relevant.

A third question involves the context. Was a study conducted in a place and time relevant to a conclusion? For example, Maynard argued that the Perry Preschool Study does not have great relevance today because the world is so different. Though it was one of the field’s greatest impact evaluations, Ypsilanti, Michigan, in the mid-1960s was a very different place than today’s world, where 70 percent of mothers are in the workforce and early childhood programs are much more common.

The Relevance of the Impact Estimates

Even if a study has relevance to a policy or practice problem, there may be issues that affect whether and, if so, how one might apply the findings. For example, does the reference period for the impact estimates match the intervention being considered, whether by a local school board, a state legislature, a parent group, or the federal government? The benefit-cost analysis could hone in on the benefits and costs that are of interest to a particular group.

A related issue is the relevance of particular estimates to the desired mission, Maynard pointed out. Does an estimate match the programmatic or policy goals? For example, someone in charge of child care policy in a state is probably not in a position to advance a program oriented toward crime prevention even if that program has good child care elements. Studies may also be relevant to a higher-level organization or may consider only the marginal treatment impacts rather than the overall impacts. It mat-

ters whether an impact estimate pertains to a primary or a secondary outcome of a study. For instance, results for secondary outcomes are more likely than those for primary outcomes to be selectively reported if the findings are favorable and ignored if the findings are null or unfavorable.

Exploratory analyses of data can inform theory and the next generation of research, but they are risky as a guide to the development of a logic model, Maynard observed. Some differences between treatments and controls will show statistical significance simply by chance. It is risky to include those measures in the same category as the outcome measures that were front and center in the original analysis.

The Causal Validity of the Impact Estimates and Reporting

Even studies that start out as well-executed randomized controlled trials can suffer from attrition (including differential attrition), measurement shortfalls, and analysis and reporting shortfalls. Matched comparison groups may differ because of untestable assumptions. Even with randomized controlled trials, the method of creating the intervention and control groups may be flawed. Finally, are the analysis methods appropriate to the sample design? Do they adequately address selection issues? “You will be surprised what happens,” said Maynard. “Really smart people sometimes do really silly things.”

Outcome measures should be based on meaningful metrics like dollars or percentile rankings, Maynard emphasized. They also need contextual information, such as the characteristics of the study sample, the intervention characteristics, and intervention context, Maynard said, along with information about the implementation of the intervention to know the fidelity with which it was carried out.

Maynard’s final plea was to eliminate standardized mean differences from reports of impact estimates. An effect size is a unit of currency, she said. An effect size that uses the standard deviation for a national sample of children is not in the same units as an effect size that uses all of the children in the bottom income quartile or who are English language learners.

Clearinghouses for the Results of Benefit-Cost Analyses

One function of clearinghouses is to reflect standards as to the kinds of studies and results that are judged to have credible evidence on particular topics. In that respect, said Maynard, it is important and useful to build on the standards being applied by existing clearinghouses. For example, the review process for the WWC includes development of a review protocol to ensure alignment and consistency, identification of the relevant literature to promote consistency and completeness, screening and reviewing of the studies using a consistent format, summarizing the findings, and archiving the findings in a shareable format. Sharing coded data and studies is particularly important, said Maynard, so that information is available to others. The WWC has been in operation for 10 years and is gaining acceptance. Researchers are designing their studies to the higher end of the standards to avoid reservations about the credibility of the reported findings. Studies are being reported out better, and data-sharing agreements are facilitating the reuse of data. It may be interesting to adopt something like the WWC standards as a “base” on which other agencies could build their evidence databases. Other agencies or those who use the standards could then tailor the standards for their own use and dissemination.

Maynard also pointed out that an interagency workgroup in the federal government is now thinking about whether there should be a common evidence platform where coded studies could be housed and information made available. Standards differ somewhat from one organization to the other. Should they be reconciled? How should their characteristics be formatted? Every standards-setting organization does not need to be the same, but where they differ should be known so differences could be mediated if necessary.

ISSUES WITH RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL DESIGNS

Several of the speakers discussed randomized controlled trials during the question-and-answer sessions. Basu expressed his concern about calling randomized controlled trials the “gold standard” for benefit-cost analysis. Such trials can have many problems, he noted, both in their design and in the data they produce. Perhaps one approach would be to

identify a checklist of criteria that alternative study designs would need to meet to be accepted.

Cook agreed that randomized controlled trials are not a gold standard if a gold standard implies being infallible. They have their own assumptions, and even a randomized clinical trial does not guarantee internal validity. Bias can arise from small selection differences, from small violations of the separate condition, and from other factors. Cook asserted that they are better than the alternatives, at least in terms of internal validity. All the other alternatives, except for regression discontinuity require full knowledge of the selection process.

Maynard agreed that the term “gold standard” is inflammatory and should not be used. Randomized controlled trials are not necessarily perfect or even better than some alternative designs, she said, because they require much more than just effective randomization. The real question is how good is the evidence. Standards could help determine whether a study is relevant or not relevant to the question at hand.

INCREASING THE COMPARABILITY OF BENEFIT-COST ANALYSES4

The ultimate goal of benefit-cost analysis is not just to look at a given program and decide whether it has a favorable economic return, said Lynn Karoly; it is to compare programs across sectors. In the early childhood sector, for example, policy makers have choices among different early childhood programs, but they also are making choices among early childhood programs, school-based programs, and prevention programs versus remediation programs. In this way, they can develop a portfolio of investments that can yield an optimal investment strategy. One of the reasons for developing standards for benefit-cost analyses is to enable such choices.

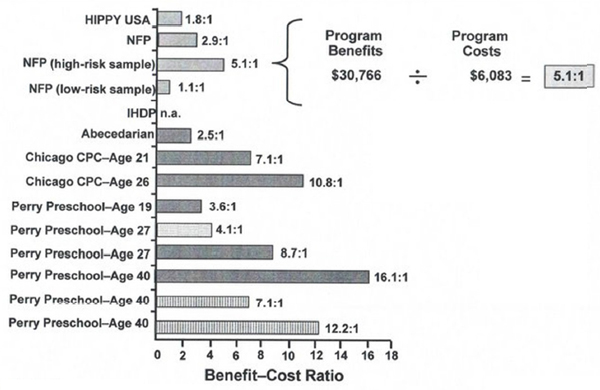

The lack of standards in benefit-cost analyses can result in the creation of differing messages. In the area of early childhood education, for example, benefit-cost analyses for six early childhood programs show a broad range of returns (see Figure 4-1). Even for the same program

___________________

4 This section summarizes information presented by Lynn Karoly, Ph.D., RAND Corporation, Arlington, Virginia.

FIGURE 4-1 The reported benefit-cost analysis ratios for early childhood interventions vary substantially.

NOTE: CPC = Child-Parent Center; HIPPY = Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters; IHDP = Infant Health and Development Program; NFP = Nurse–Family Partnership.

SOURCE: Adapted from Karoly, 2012.

following subjects to the same age, results can vary markedly when different methods are used.

A basic question is how much of the differences derive from choices the analysts are making in performing benefit-cost analysis, Karoly observed. The studies differ along a number of dimensions, including the age at follow-up, discount rate, discount age, whether the results are disaggregated by stakeholder, and whether standard errors are reported (see Table 4-1). For example, some of the studies discount the benefits and costs to age three, while others discount them to birth. The studies also use a wide range of discount rates. Further, studies do not always disaggregate the results by stakeholders, such as the government, taxpayers, or society as a whole.

All of the studies have performed some kind of sensitivity analysis, Karoly continued. For example, they may have disaggregated estimates of benefits to show the different sources of benefits, such as the benefits

TABLE 4-1 Variation in Methods in Application of Benefit-Cost Analysis to Early Childhood Programs

| Program | Age at FU |

Discount Rate(s) |

Discount Age |

Disaggregate by Stakeholder |

SEs | Sensitivity Analysis |

| HIPPY | 6 | 3 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Some |

| NFP (WSIPP) | 15 | 3 | 0 | Yes | Yes | Some |

| NFP (RAND) | 15 | 4, 0–8 | 0 | Yes | Yes | Some |

| IHDP | 8 | 3 | 0 | Yes | Yes | Some |

| Abecedarian | 21 | 0, 3, 5, 7, 10 | 0 | No | No | Some |

| Chicago CPC | 21 | 3, 0–7 | 3 | Yes | No | Some |

| Chicago CPC | 26 | 3, 0–7 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Some |

| Perry–Age 19 | 19 | 3 | 3 | Partial | Yes | Some |

| Perry–Age 27 | 27 | 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11 | 3 | Partial | No | Some |

| Perry–Age 27 (RAND) | 27 | 4, 0–8 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Some |

| Perry–Age 40 | 40 | 0, 3, 7 | 3 | Partial | No | Some |

| Perry–Age 40 (Heckman) | 40 | 0, 3, 5, 7 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Some |

NOTE: CPC = Child–Parent Center; FU = follow-up; HIPPY = Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters; NFP = Nurse–Family Partnership; SEs = standard errors.

SOURCE: Adapted from Karoly, 2012.

to be gained by a reduction in crime. Decision makers then can adjust their use of the results based on the sensitivity analysis. In other cases, sensitivity analyses look at the effects of basic assumptions in the model, such as the size of the dead weight loss from taxation. Similarly, most of the studies report standard errors, though some also report the percentage of time that a positive net benefit would be expected.

Establishing Base Cases

One way to increase the comparability of benefit-cost analyses, both within the early childhood domain and across policy areas, would be to identify a base case or standard case on which analysts could agree, Karoly said. Researchers then could make the case for an alternative analysis of the data but only after presenting results for the base case. For example,

regarding the appropriate real discount rate, a base case can be used along with a sensitivity analysis using alternative discount rates. A similar approach could apply to the preferred age to discount costs and benefits. With regard to uncertainties, in addition to reporting standard errors, the percentage of simulations with positive net benefits could be reported in the base case, a useful and intuitive result for decision makers. Other areas of uncertainty, such as the methods for projecting future benefits, assumptions about the efficacy of scale-up, or distributional weights, could be better addressed with sensitivity analyses.

Karoly also urged that attention be given to the proper outcomes or summary measures from benefit-cost studies. If only a benefit-cost ratio is reported, it can be difficult to recover the numerators and denominators. In addition, measures like the internal rate of return or benefit-cost ratios will not necessarily order projects in the same way as would net benefits. These issues could be addressed by the use of a reliable internal rate of return or by adjusting the benefit-cost ratio for projects of different size.

Karoly emphasized that the analysis of costs produces value in its own right, even if it does not lead to a benefit-cost analysis. If a good cost analysis were done as part of every program implementation, it would be available should a benefit-cost analysis be warranted. She also emphasized the role that administrative data can play, both in short-term evaluations and in learning about long-term impacts. If assessment of potential long-term impacts is built into a program evaluation from the beginning by linking to administrative records, evaluation costs would be lower.

Standardization may be easier in some areas than in others, Karoly acknowledged. The easier issues to address include valuing program costs, the discount rate, the age to discount to, accounting for uncertainty, sensitivity analysis, disaggregation by stakeholder, and reporting results. Harder issues to address include the right baseline to use, the length of follow-up, the outcomes measured, the use of shadow prices, and the projection of future outcomes for participants, family members, peers, and descendants.

EXPRESSING UNCERTAINTY IN BENEFIT-COST ANALYSES5

As Anirban Basu pointed out, expressions of uncertainty are rare in policy analysis. In particular, both cost-effectiveness and benefit-cost analyses often report their results as point estimates without expressions of uncertainty. Yet policy predictions often rest on unsupported assumptions or leaps of logic, rendering expressions of certitude not credible (Manski, 2011).

Though no empirical evidence exists on the issue, researchers tend to assume that policy makers do not want to know about uncertainties. As Lyndon Johnson once said, “Ranges are for cattle. Give me a number.” But even if a decision maker does not want to know about uncertainty, the uncertainty remains important, Basu insisted, because the production function for the data is often nonlinear with respect to its many inputs. With a nonlinear function, the expectation of the function is not equal to the function of the expectation of inputs. Thus, using point estimates as the input to a model can generate a very different result than when incorporating the uncertainties around those inputs.

Forms of Uncertainty

Another way to look at a production function is to recognize that it is inherently heterogeneous, said Basu. This heterogeneity can be divided into scientifically known heterogeneity, such as age effects or gender differences, and scientifically unknown heterogeneity (the unknown unknowns), which is known to exist but cannot be explained. The scientifically known heterogeneity can in turn be divided into heterogeneity that is directly observable for the decision maker or analyst (the known knowns) and heterogeneity that cannot be observed (the unknown knowns).

The unknown unknowns and unknown knowns together create stochastic uncertainty, parameter uncertainty, and structural uncertainty in a model, Basu observed. Stochastic uncertainty is used to study random variation across individual outcomes, often using Monte Carlo techniques. Parameter uncertainty is used to study variation in expected outcomes through probabilistic approaches, especially second-order Monte

___________________

5 This section summarizes information presented by Anirban Basu, Ph.D., University of Washington, Seattle.

Carlo simulations. Finally, structural or model uncertainty is used to study variation in expected outcomes and individual outcomes. There is no clear consensus on how to study such uncertainty, though common approaches are sensitivity analysis and model averaging.

Unexplained variations in expected outcomes lead to decision uncertainty, said Basu. Decision uncertainty can be expressed in different ways, depending in part on what a decision maker wants to know. One approach is to give 95 percent confidence intervals for a benefit-cost ratio. Another is to give a 95 percent confidence interval for net monetary benefits. A third is to provide acceptability curves, which relate the probability of acceptance of an intervention to the willingness to pay for a given benefit at a given cost. Each of these three methods provides exactly the same information about uncertainty in benefit-cost or cost-effectiveness analyses. Which is chosen depends on the research and on the decision maker’s comfort in understanding heterogeneity.

Acceptability curves can be linked directly to decision making for future research, Basu pointed out. The expected value of perfect information about a policy is the product of a probability that a decision made today is wrong multiplied by the loss due to a wrong decision. This simple product provides an upper bound on the value of future research and can be used to inform many decisions, such as whether to fund future research, how to prioritize across future research proposals, and how to design future research studies.

THE POTENTIAL COMPENSATION TEST AND DISCOUNT RATES6

Richard Zerbe discussed two contentious topics in the area of benefit-cost analysis. The first is the idea of the potential compensation test and the second is on discount rates. The first holds that if the winners from a project could in theory compensate the losers, without considering interpersonal comparisons of utility such as income distribution, then the project is beneficial. This criterion is not satisfactory, said Zerbe, for several reasons.

___________________

6 This section summarizes information presented by Richard Zerbe, Ph.D., University of Washington, Seattle.

First, the idea that such compensation could exist is clearly a fiction, Zerbe pointed out. In fact, the cost of compensating losers in a particular project would in many if not most cases be greater than the net value of the project itself. Second, Zerbe explained that the potential compensation test does not always work in the realm of law. When disputes arise, the sum of the expectations of the parties generally exceeds the total value available. A potential compensation test therefore would not succeed. Nevertheless, benefit-cost principles can be used to make decisions in that case without becoming hung up on the potential compensation test. Third, the potential compensation test leads to what are known as Scitovsky reversals, in which moving from state A to state B is beneficial, but moving from state B to state A also is beneficial.

Finally, a better alternative is available, Zerbe stated. When considering a portfolio of benefit-cost projects, a person who loses and pays taxes to support one project can gain from another project. Because each project can be expected with a probability greater than 50 percent to have net gains, in the end almost everyone wins. This is true even if some projects do not pass a benefit-cost test or if some gaming of the system occurs.

Discount Rates

The second topic Zerbe discussed is discount rates. A wide range of discount rates can be justified, from 0 to 30 percent or more, according to Zerbe. Furthermore, the literature on discount rates is confusing and disparate.

One rate that has been suggested is the rate of return to private investment, which Zerbe and his colleagues have calculated to be about 8.5 percent in real terms. Other approaches are to use a weighted average of the rate of return and time preference rates, a social welfare function, or a time-declining rate, which can be combined with the other approaches. Investment in a public project displaces some private capital, and some of the investment comes from a reduction in consumption. The proportions that come from private capital and the proportions that come from a reduction in consumption can be used to calculate a rate that represents the opportunity cost of capital, which Zerbe has calculated to vary between 6 percent and 8 percent.

Zerbe added that the consumption rate of interest, which can be thought of as a pretax private return to individuals, is generally calculated to be about 3.5 percent. It is too expensive to anticipate for each project where the funding is coming from exactly, so 6 to 8 percent is a project average. Zerbe indicated that a case can be made for rates as low as 3.5 or as high as 8.5 for particular projects.

The only way to develop a rough consensus on discounting, Zerbe concluded, is to develop fundamental principles that can be used to decide on the rate. One such principle is that ethical considerations and other extraneous considerations, such as environmental goods or the value of life, should be excluded from the discount rate. These factors can be included in values and thus in benefit-cost analyses through willingness to pay tests, but they should not be included in discount rates. A second principle is that a discount rate should require that no project be accepted if its return is less than the return available on alternative projects. This is a straightforward opportunity cost rationale, Zerbe said.