4

Co-Administration of Research and Services

OVERVIEW

This study was conducted against a background of shifting opinion within Congress and among constituency groups about the roles, responsibilities, and organization of federal agencies that administer health-related research and service programs. Congressional legislation over the past five years has increased federal oversight of block grant and demonstration programs. Increased funding and authorization of new demonstration programs, as well as large increases in block grant funding for drug abuse treatment programs, brought with them increasing interest by Congress to ensure that funds were reaching their target populations. New offices and programs were created within the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA) to administer a complex of treatment and prevention programs for drug abuse. In another example, a new agency was created in the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) as recently as the spring of 1991 to provide a focus for federal demonstration and block grant activities related to children and families.

As noted in the introduction to this report, the committee agreed at its inception to conduct a study that would explore the pros and cons of co-administration of research and services programs at different levels of the Public Health Service (PHS): the institute, bureau, or office level; the agency level; and the level of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. The committee sought to determine the effects of co-administration of research and service programs in three areas: (1) organizational goals and level of funding at the institute and agency level, (2) clarity of the missions of the PHS as a whole and of individual agencies, and (3) relationships with constituency groups.

However, the effectiveness of the organization of research and service activities is also expressed (4) in management functions such as planning, priority setting, and budgeting; (5) in the creation of mechanisms to allow for timely response to new information and policies such as research information and service problems; (6) in the development of mechanisms for effective dissemination of research findings into clinical practice, as well as for identification and translation of clinical issues into research priorities; and (7) in mechanisms for recruitment and retention of talented leadership. The committee evaluated each of these functions for ADAMHA and, as appropriate, for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), as well as for the Public Health Service (PHS) as a whole.

This chapter begins with a discussion of the goals and missions (including funding) of the PHS and its agencies and then moves to a discussion of the research–services continuum—the relationship between research and services programs in the PHS. It continues with a discussion of management issues, including planning, priority setting, and budgeting; timeliness of response to new information and policies; and dissemination. It then discusses organizational effectiveness as seen in research, demonstration, and services development programs and concludes with a discussion of organizational capacity and program placement.

RESEARCH AND SERVICES MISSIONS OF THE PHS

Congressional authorizations and statements of mission strongly influence the “culture” and activities of government organizations. Within DHHS, in some instances, the management of programs is assigned to a specific agency. In other instances, management is assigned to the Secretary, who may delegate primary program responsibility to one or more specific DHHS components. A department or an agency's mission is the purpose for which it was established. However, missions are more than statements of task. Goals and missions “describe what it is hoped the organization 's activities will do and produce; they say something about what and who is important. . . .” 1

While goals and missions, in and of themselves, do not define the organizational structures that are required to carry them out, they do define the arena within which government organizations can operate and the activities for which they will be held accountable. As

statements of purpose, missions heavily influence both the culture of federal organizations and their structures. Controversy over the goals that a government organization should pursue, however, can create significant obstacles for the performance of a government organization.

To many current federal administrators and constituency groups interviewed for this study, the missions of NIH and ADAMHA are the same. To others, the greater apparent broadness of ADAMHA's mission (which includes dealing with “health problems and issues associated with the use and abuse of alcohol and drugs, and with mental illness and mental health” 2 ) suggests significant differences from NIH in its responsibilities related to clinical applications and funding of services. Interviews with current agency and institute directors, as well as with constituency groups, point out that the basic biomedical and clinical research mission of NIH and ADAMHA is in little doubt. A review of the history of the PHS and its agencies suggests that clarity about the research mission of the PHS has been a critical factor in the growth and development of research programs and structures within NIH institutes and, increasingly, within ADAMHA institutes.

Interviews conducted with current agency and institute directors suggest that the ability to achieve a coherent federal mission at the agency, institute, or bureau level is important for a number of reasons. Primary among them is that a coherent mission allows for the consistent recruitment of institute and agency executives with similar backgrounds. Achieving such a mission can be impeded, however, by external factors that have an impact on how the organization perceives its mission. Differences of opinion among multiple and often fragmented health constituencies as well as the political autonomy of state and local governments (combined with grants-in-aid, e.g., formula grants over which secretaries and directors have little direct control) can affect the way an agency defines its purpose. During the 1980s, for example, the priorities of ADAMHA, in the view of most constituency groups, shifted from services to research. Interviews with constituency groups indicate that the shift has been viewed positively by the constituent community with research interests. It has been viewed negatively, however, by a number of services-related groups that have continued to look to ADAMHA for national leadership on such policy issues as reimbursement for mental health and substance abuse services. These groups expressed particular concern that, as the institutes within ADAMHA redefined their missions, previously assumed leadership roles in services policy have diminished or disappeared and have not been

taken up structurally at other levels of the organization. As ADAMHA institutes have become more focused on biomedical research, therefore, services-related constituency groups have shifted their efforts either to other organizational units within ADAMHA that are more directly related to their concerns (e.g., the Office of Treatment Improvement [OTI], the Office of Substance Abuse Prevention [OSAP]) or to agencies outside of the PHS.

Interviews conducted for the committee's analyses of demonstration and block grant programs confirm the finding of the Lewin Report of 1988: the shift to block grant funding of most health-related services in the early 1980s resulted in a decrease, if not total elimination, of the federal role in transforming the way basic services are provided at the local level and in ensuring that monies directed toward populations with special needs indeed reach them. There remains significant confusion about the PHS mission with regard to services development, especially regarding expectations for services funded through block grants that are administered by the states. Although it is well known among the states that federal oversight of block grant programs (particularly with regard to drug abuse) has increased in the past several years, officials in OTI and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) have noted, for instance, that many state program directors seem bewildered by and resistant to planning and needs assessments related to block grant programs.

The problems that arise for federal agencies from conflicts between the agendas and expectations of Congress and the administration can be formidable. The administration and Congress often fail to define their goals clearly, and when they do define their goals with some precision, they often conflict. Even when the administration, Congress, and the agencies are in some agreement about their goals, they may disagree about how to accomplish what they want to accomplish. Although the administration and Congress are powerful in setting the agenda for federal agencies, “they do not necessarily control the alternatives among which authoritative choices might be made. 3 ” These conflicts can result in insufficient resources being applied to a problem, inability to develop appropriate organizational structures for implementation, simple failure to initiate a program, or a deluge of demands for clarification of new legislation in the face of established, perhaps long-standing, policies that move in the opposite direction.

Interviews for the study also revealed that confusion exists among both constituency groups and federal administrators about the direction and importance of block grant programs in relation to other parts of ADAMHA's mission. On the one hand, the block grant pro-

gram is viewed in OTI and in ADAMHA as part of a research–services continuum and as an important step in the process of implementation of demonstrations. On the other hand, agency officials point out that the purpose of block grants is to reduce federal oversight and provide autonomy in planning and priority setting to states and localities.

One outcome of the discrepant views of the administration and Congress about the importance of block grant programs to the missions of ADAMHA and HRSA seems to be unstable organizational placement of services demonstrations and block grant administration. In a number of instances, the agencies and organizational units that administer services development and block grant programs are not congressionally authorized (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control [CDC], HRSA, and OTI). Since the enactment of block grant legislation for funding of services programs in 1982, the organizational unit within ADAMHA responsible for administration of block grants has shifted eight times. Within HRSA, an apparent lack of political agreement on the services mission of the PHS has led to great difficulty in integrating diverse service delivery programs as well as confusion and disagreement among the administration, Congress, constituency groups, and agency staff about the appropriate balancing of priorities. During the eight years of HRSA's existence, programs have been added and deleted, changes in direction have been proposed by the administration and Congress (only occasionally in the same direction), and bureaus have been added and deleted, split and combined. “In part . . . organizations such as HRSA are more bureaucratic in nature and need competent bureaucratic/administrative leadership because their mission comes largely from the political process. Their job is to execute political programs efficiently.” 4

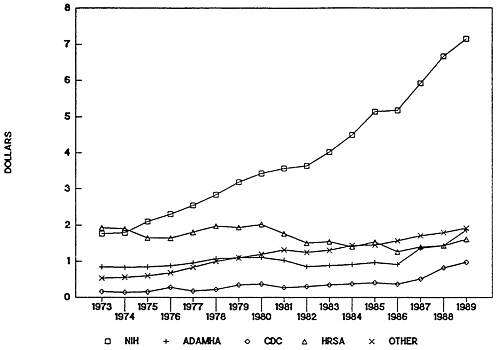

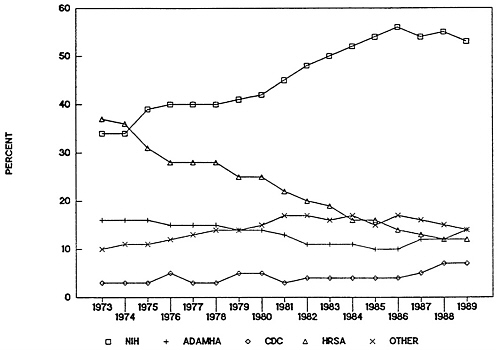

These constant programmatic changes appear to indicate ambivalence about the services mission of the PHS. Whether this ambivalence emanates from Congress, the administration, or agency leadership and personnel themselves, the result has been a failure to develop adequate, appropriate organizational capacity and mechanisms for enacting services development and demonstration programs. Allocations for HRSA, for example, have declined steadily beginning in 1977 and at an increasing rate since the passage of block grant legislation in 1982 (Figure 4-1 and Figure 4-2 ). No clear evidence could be found to support a cause-and-effect relationship, but some relationship is suggested between the decline in allocations and ambivalence about the services development and demonstration mission of the PHS. Also seemingly related to this trend is the lack of health services research capacity within HRSA that has made it difficult for that agency to

FIGURE 4-1 Public Health Service budget obligations in constant dollars, 1973–1989. Abbreviations: NIH, National Institutes of Health; ADAMHA, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; CDC, Centers for Disease Control; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration.

SOURCE: Public Health Service Budget Office.

FIGURE 4-2 Public Health Service budget obligations as percentage, 1973–1989. Abbreviations: NIH, National Institutes of Health; ADAMHA, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; CDC, Centers for Disease Control; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration.

SOURCE: Public Health Service Budget Office.

evaluate and defend the effectiveness, efficiency, and outcomes of its programs.

Interviews conducted with constituency groups suggest that shifts in the organizational placement of programs have made it difficult for services-related constituency groups to maintain contact with federal agencies on specific issues related to their areas of interest or to build working relationships and trust with agency and institute programs. In many instances, constituency groups have expressed dismay about changes in organizational arrangements that are perceived as eliminating or reducing the standing of programs that had served as focal points for their concerns.

The committee believes that clarity of mission is critical to accountability and to the exercise of programmatic responsibility. To facilitate accountability within the PHS regarding the objectives of services development and demonstration programs, the committee recommends that the Secretary of Health and Human Services further clarify the services mission of the PHS (and of the agencies that administer programs related to development of the structure and delivery of services). Services programs should be given stability, including stability of organizational location, financing, personnel, and other resources.

When responsibility for research and services development and demonstration programs for a single problem (such as substance abuse among pregnant women) is divided among several agencies, the difficulties of communicating and collaborating across agency boundaries can also inhibit success in addressing the problem. The case study of substance-abusing pregnant women pointed out that federal agencies tend to work alone unless forced to do otherwise, or unless a well-defined need presents itself. The case study notes, as a case in point, the lack of relatedness, until quite recently, between ADAMHA institutes and offices and HRSA 's maternal and child health programs.

Federal legislation requires maternal and child health agencies to work collaboratively with Medicaid and other federal programs. Until very recently, however, neither Congress, nor the Maternal and Child Health Bureau in HRSA, nor ADAMHA had considered the need for collaboration between the two agencies in relation to substance abuse and pregnant women. Further, although HRSA has direct responsibility for funding primary care programs in states and localities, where a significant majority of substance-abusing pregnant women are likely to be seen (if they are seen at all), little effort was made within

the PHS until this past year to incorporate substance abuse programs into primary care settings.

Agencies may develop effective programs in isolation from each other, but implementation will probably be fragmented unless due attention is paid to settling jurisdictional disputes and creating mechanisms (at the level of DHHS) to increase collaboration across agencies. For example, a recent General Accounting Office report on drug-exposed infants made a number of recommendations that cut across agency lines: at least two related to block grant services administered by ADAMHA; two others related to support services administered by HRSA; and another related to reimbursement of services by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA).

There is no guarantee that several agencies working on a common problem, such as drug-exposed infants, will develop an integrated approach to the problem. The committee believes that integration of the programmatic objectives of services development and demonstration programs within the PHS is vital to the success of these programs. Attempts to integrate programmatic objectives related to science and research within the PHS (e.g., the Council on Alzheimer's Disease) seem more impressive than efforts to integrate the objectives of services development and demonstration programs. The committee recommends that the Assistant Secretary for Health take responsibility for assessing and enhancing the integration of program objectives related to the services mission across agencies in the PHS.

THE RESEARCH–SERVICES CONTINUUM

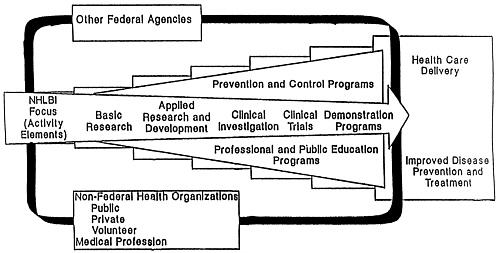

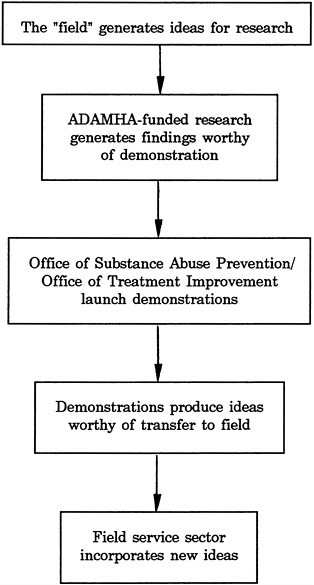

The ultimate goal of biomedical research is improved health of the population. One presumption that seems to lie behind questions about the effectiveness of co-administration is that biomedical research and services development and demonstration programs exist along a continuum, the end result of which is nationwide diffusion of clinical practices, technologies, and system innovations (Figure 4-3 ).

FIGURE 4-3 The classic research and development continuum.

In theory, a continuum does exist between research and services provision, but in practice, it is difficult to find mechanisms within any of the PHS agencies for carrying it out. Some models of this continuum move from basic research to clinical trials; other models include movement from basic research to changes in the structure and delivery of health care services. The utility of both kinds of models is that once the notion of stages is established, one can address the question of how to transfer knowledge from the beginning of the process through to the end. However, there are no fixed criteria to distinguish between basic research, applied research, and development, nor does the naming of these stages assist in understanding the actual processes involved in moving from one stage to another.

Some PHS agencies and institutes operate on only a portion of the research–services continuum, while others span most or all of the spectrum. Six NIH institutes (the National Cancer Institute [NCI], the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [NIDDK], the National Institute of General Medical Sciences [NIGMS], the National Institute of Dental Research [NIDR], and the National Institute on Aging [NIA]) have statutory authority to support basic and applied research, clinical investigations and trials, and demonstrations. This authority sets them apart from the more limited missions of other NIH institutes.

Although NIH has often been under pressure to expand its activities to include greater emphasis on applications, it has successfully resisted numerous attempts to alter its basic mission as a biomedical research agency. Most NIH institutes, for example, provide very limited funding for health services research. This was attributed, in many interviews and discussions, to the functional organization of much of the PHS, in which the mission of health services research is primary to another unit, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR).

One of the expectations in the creation of ADAMHA in 1973 was that the administration of research and services development or demonstration programs in a single agency would result in easier information transfer to the health delivery system. ADAMHA has a statutory mission to administer both (1) basic and clinical biomedical and behavioral research and (2) demonstration and services development programs. All of the ADAMHA institutes (NIMH, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], and the National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA]) are authorized to support and conduct basic and clinical research, research training, and demonstrations. In addition, NIMH is authorized to support and administer

service development programs such as the Community Support Program (CSP) for adults with severe, long-term mental illnesses, and the Child and Adolescent Service Support Program (CASSP).

Critics object that this linear model of the continuum is not a useful concept. As a previous study of research and development programs in NIH noted:

Trying to capture important technical and social complexities in a one-dimensional continuum oversimplifies and obscures some critical organizational processes such as transferring knowledge produced in one part of the organization to other parts, or the organization 's response to the concerns of groups in the environment. 5

Exclusive reliance on the classic, linear model has also been responsible, at least in part, for the lack of explicit attention to coordinating the various objectives of federal research and services programs.

Most of the scientific community believes that, to protect the creativity of investigators and the vigor of research, planning of research should be done by scientists using scientific criteria. For others, however, the best way to ensure progress is through targeted research efforts, maximizing immediate returns on invested tax dollars. Previous studies of medical science have been critical of this narrow, short-term approach on the basis that scientific break-throughs often come where least expected:

Planning for future clinical advances must include generous support for [basic, fundamental, undirected, nontargeted research] that bears no discernible relation to a clinical problem at the time . . . [of its inception] . . . because it pays off in terms of key discoveries almost twice as handsomely as other types of research and development combined. 6

Or, as former NIH director James Shannon argued, an overemphasis on the immediately practical tends “to limit the likelihood of an ultimate solution of the more important problems of medicine within any reasonable time frame.” 7

These differing views have led to tension between “those who advocate increased funds for basic research, those who feel more work is needed in applying more fully the knowledge and technologies that exist, and those who believe that it is important to examine what is already in place to determine how it is working and how to make it work better.” 8While the importance of applied research has not been

at issue, a good deal of debate has occurred about the appropriate amount of resources to devote to applied research relative to basic research. The need for applied research, at a particular time and in a specific area of research, is often dependent on the basic knowledge that is available to be applied.

The relationships among applied research, applications, and implementation are less clear than the relationship between basic and applied research. As Beryl Radin notes in her background paper on linkage mechanisms, “The specific formulation depends on the nature of the policy area, the difference in federal policy roles related to the area of concern, the nature of the population with the problem, and the type of research required.” 9

In the last decade, as pressure has mounted for tangible results of biomedical research, Congress has expressed its clear intent that demonstrations, information dissemination, and technology transfer be an important part of the activities of all federal agencies engaged in research. For example, the Stevenson-Wydler Act of 1980 mandated that all federal agencies with significant research and development budgets set aside 0.5 percent of those budgets for technology transfer activities. The Technology Transfer Act of 1986 created additional incentives for the transfer and application of technologies developed from federally funded research to scientists and health professionals as well as to industry.

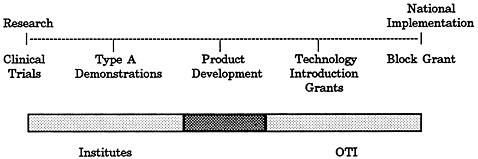

Models of this process (basic research leading to applications, demonstrations, information dissemination, and implementation) have been developed by a number of NIH institutes (among them NHLBI [Figure 4-4] and NCI) as well as by ADAMHA (Figure 4-5 ) and one of its offices, the Office for Treatment Improvement (OTI) (Figure 4-6). Each of the models represents the desirable sequence of component stages, but the process is far less linear or systematic than the models imply. Demonstrations and control programs occupy a critical position in the models for testing the feasibility of widespread use of new practices and systems innovations prior to dissemination. The effectiveness of these models in providing a framework for the development of administrative mechanisms within agencies and institutes is discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

CO-ADMINISTRATION OF RESEARCH AND SERVICE PROGRAMS

As noted in Chapter 1 , the recent reorganization of ADAMHA (with the formation of OSAP and OTI and the increased focus of

FIGURE 4-5 Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration research-services “paradigm.”

SOURCE: R. Schmidt, “Research Planning and Priority Setting in the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration,” paper prepared for the IOM Committee on Co-Administration of Service and Research Programs of the NIH, ADAMHA, and Related Agencies, 1991.

FIGURE 4-6 OTI treatment improvement model.

SOURCE: L. V. Klerman and M. A. Johnson, “Case Studies of Substance-Abusing Pregnant Women,” prepared for the IOM Committee on Co-Administration of Service and Research Prograrrs of the NIH, ADAMHA, and Related Agencies, 1991.

ADAMHA institutes on research) has created, de facto, organizational units within the agency that do not differ significantly in their goals and objectives from the research, prevention, and services goals of NIH, CDC, and HRSA, respectively. Interviews conducted for the case study of substance-abusing pregnant women and for analyses of planning and priority-setting processes indicated that this functional reorganization (which removed responsibility for administration of many demonstrations and much of the block grant program from ADAMHA institutes) has allowed programs housed in NIMH, NIAAA, and NIDA to focus almost exclusively on research and thereby to grow and develop.

The basic biomedical and clinical research missions of NIH and ADAMHA are very clear. The stated mission of NIH is more exclusively focused on research and research-related activities, including a few demonstration and control programs and some dissemination activities. Some view the “narrowness” of NIH's mission as supportive of more effective research programs; of enhanced communication among NIH institutes, constituency groups, and Congress; and of consistent recruitment of talented agency and institute executives. Others view the NIH mission as restrictive: the case studies of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease pointed out that NIH institutes restrict their mission to exclude much-needed health services research related to costs and effectiveness, for example, because it is viewed as falling within someone else's jurisdiction.

Clarity about the research mission of the PHS, according to science administrators and others interviewed for each of the case studies, has protected and supported the development of research programs and structures within NIH institutes and, in the past 10 years, in ADAMHA institutes. These structures, in turn, have permitted the research enterprise to develop. The effectiveness of biomedical research programs within NIH has often been attributed to the ability of the research institutes to defend their boundaries and limit their mission to research. Not surprisingly, therefore, interviews conducted with current institute division directors in ADAMHA for the case studies of schizophrenia and substance-abusing pregnant women, as well as for analyses of demonstrations and block grant programs, indicated that programs administered by research institutes, if they are not directly related to their basic and clinical research missions, are viewed as stepchildren and may not be appropriately incorporated into planning and priority setting. It is the impression of many current science administrators in federal agencies as well as other scientists interviewed for this study that in the last 5 or 10 years the research programs of ADAMHA institutes have benefited from an increasingly singular research focus. In case studies and interviews conducted for other background papers, the suggestion was made (almost uniformly by science administrators as well as policy analysts) that —at the level of institutes, bureaus, and offices—co-administration of research and service programs can retard the productivity of both programs through dilution of time, energy, and financial resources and increased difficulty in leadership recruitment.

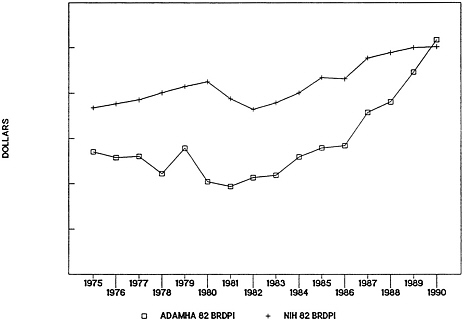

Following the 1982 shift to the block grant for funding service development and demonstration programs, a number of other changes occurred in ADAMHA. Those changes include (1) the reduction of responsibility for administering prevention programs and service development programs in NIMH, NIAAA, and NIDA (with the exception of a few remaining programs in NIMH); (2) increases in research allocations to ADAMHA institutes; and (3) greater differentiation in the organizational structure within institutes. It is tempting to see a direct relationship between the change in funding mechanism and the increases in research funding in ADAMHA (Figure 4-7 ). No firm evidence could be found supporting such a relationship, although a number of current agency and institute staff suggested that decreasing responsibility for services development and demonstration programs and increasing focus on research were positively related to increased allocations to research.

FIGURE 4-7 Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) research appropriations in 1982 constant dollars (1982 Biomedical Research and Development Price Index [BRDPI]).

SOURCE: R. Walkington, “Allocations in the Public Health Service,” paper prepared for the IOM Committee on Co-Administration of Service and Research Programs of the NIH, ADAMHA, and Related Agencies, 1991; adapted from information provided by the National Institutes of Health and the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration budget offices.

The committee recommends that, below the agency level, research and services programs be administered and conducted by separate institutes or offices that have substantial expertise in the specific substantive and functional area. In cases where ADAMHA institutes currently have responsibility for treatment services demonstrations, service development, or block grant compliance programs, for example, such programs might be placed more appropriately in an organizational unit that currently has responsibility for similar programs, along with staff of sufficient expertise in the substantive area to manage the programs effectively.

The organizational shifts that occurred with the enactment of the block grant program seemed to lead ADAMHA away from co-admin-

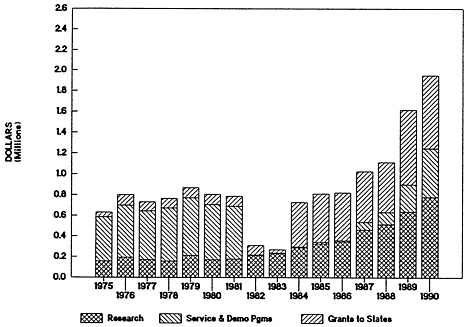

istration during the early 1980s. Block grant funding was viewed as a federal “pass through” to the states; little if any decision-making authority for services development and demonstration programs remained with federal administrators. In the years immediately following the block grant legislation, therefore, ADAMHA construed its mission more narrowly as focused on research. Recently, however, with increases in federal oversight of the block grant program and in funding for demonstrations, the effectiveness of co-administration in ADAMHA has again surfaced as a concern. Questions were raised in the case studies of schizophrenia and substance-abusing pregnant women about whether the increasing service component of ADAMHA might make it difficult in future to ensure stable scientific leadership at the agency level. It was pointed out in the analyses of planning, priority setting, and budgeting that within ADAMHA, block grant and demonstration programs have become increasingly significant responsibilities of the administrator. Allocations data show that funding for demonstration programs in ADAMHA has been increasing since the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 ( Figure 4-8 and Figure 4-9 ). Interviews with current agency administrators and staff attribute this increase to greater congressional concern (beginning in the mid-1980s) about a lack of federal leadership in services development at the state and local levels.

Divergent views exist about how to interpret longitudinal data on research allocations to NIH and ADAMHA. On the one hand, the similarity of increases in funding for biomedical research in NIH and ADAMHA does not support the perception that allocations to biomedical research have suffered in the last 10 years within a categorical agency responsible for both research and services development and demonstration programs, in contrast to a functional agency such as NIH. In fact, in the past 5 years it appears that funding for research has fared somewhat better in ADAMHA than in NIH. On the other hand, over a longer period of time, perhaps 20 years, one might interpret the data as suggesting that during the 1970s research allocations to ADAMHA and its predecessors suffered and only began to recover following passage of the block grant legislation and some internal reorganization of ADAMHA. A number of current science administrators and science policy constituency groups interviewed for this study suggested that research allocations to ADAMHA in the 1970s may have been hurt by negative perceptions of early social research; recent research allocations to ADAMHA may have been helped, on the other hand, by perceptions of drug abuse and AIDS as major social problems. The longer the time span one considers, the more the allocations data are susceptible to contradictory interpretations.

FIGURE 4-8 Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration expenditures by major purpose (in constant dollars): 1982—passage of block grants to states; 1986—passage of Anti-Drug Abuse Act.

SOURCE: R. Walkington, “Allocations in the Public Health Service,” paper prepared for the IOM Committee on Co-Administration of Service and Research Programs of the NIH, ADAMHA, and Related Agencies, 1991; adapted from information provided by NIH and ADAMHA budget offices.

Given the complexity of administering federal research and service programs, functional organization (i.e., the administration of research, services development, and prevention programs by three separate agencies, namely, NIH, HRSA, and CDC) can be helpful in allowing for the development of specialized skills that lead to improved performance. Analyses conducted for this study and previous studies suggested that, while the administrative and political dictates of research and service programs differ (and, therefore, specialization may be useful), these differences often result in conflicting if not mutually exclusive priorities. These analyses pointed out the need to pay attention to jurisdictional disputes and overlapping responsibilities and, to avoid fragmentation in the implementation of policies and

FIGURE 4-9 Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration expenditures by major purpose (as percentage). Expenditures do not sum to 100 percent because training is omitted: 1982—passage of block grants to states; 1986—passage of Anti-Drug Abuse Act.

SOURCE: R. Walkington, “Allocations in the Public Health Service,” paper prepared for the IOM Committee on Co-Administration of Service and Research Programs of the NIH, ADAMHA, and Related Agencies, 1991; adapted from information provided by the NIH and ADAMHA budget offices.

programs, the need for a focused effort to increase collaboration across research and service programs in the PHS.

Other evidence presented in the case studies and in the analysis of planning and priority setting did not suggest that co-administration of research, prevention, and service development programs was a guarantee of any specific relationships among the programs. Nor did it suggest that research findings were translated more effectively or benefited patients more quickly under the organizational structure of either ADAMHA or NIH. At the agency level, no evidence could be found that organizational structure bears any necessary relation to allocations for research or services development and demonstration programs. Because it found no persuasive evidence that overwhelmingly supports any specific agency structure, the

committee recommends that agency-level organization not be used as the basis for deterring or encouraging reorganization. If reorganization of current agency structure is considered, it should be justified purely on policy grounds.

PLANNING, PRIORITY SETTING, AND BUDGETING

The effectiveness of ADAMHA, NIH, and other PHS agencies is dependent on their ability to carry out such management functions as planning, priority setting and budgeting; responding to new information and policies; disseminating research findings; coordinating programmatic objectives; and recruiting and retaining leadership. To balance the needs of research, applications, and services development and demonstration programs, an organization must possess criteria for setting priorities, evaluating work in progress, assessing relationships with other organizations, and guiding action.

Commissioned analyses of institute-, agency-, and PHS-level processes conducted for this study show that planning, priority setting, and budgeting differ according to the culture and organizational structure of each of the PHS agencies. Assertions have been made throughout the history of the PHS that co-administration makes planning significantly more difficult and that priority setting and budgeting exact trade-offs between research and service programs. These discussions have centered on agencies such as ADAMHA and, before its creation, institutes such as NIMH that had responsibility for administering both research and services programs.

An important question for this study of co-administration was whether specific mechanisms existed for relating the program objectives of research, prevention, and service development and demonstration programs within ADAMHA and among the relevant agencies of the PHS. In addition, the committee wanted to clarify the similarities and differences in the programmatic objectives and priorities across research and service programs in the PHS and in ADAMHA.

At the Department and PHS Level

The policymaking system is complex, changing, convoluted, and (since public financing is involved) inherently political. In fact, there are at least two systems operating simultaneously, frequently with only minimal coordination: program planning (i.e., the content of the programs) and the budget planning and review process (which deter-

mines how much money will be available for a particular activity). This dichotomy is particularly evident with regard to the research programs of ADAMHA and NIH, where the budget review process rarely becomes involved with the actual content of the research programs, which is left to the individual institutes, divisions, and disciplinary study sections. The result is constant tension between long-range, science-based planning at the programmatic level within institutes and the yearly, policy-based priority setting conducted by Congress and the administration. This latter process, by its very nature, is political.

There is no single, coherent system that can be labeled priority setting; rather, it is the result of myriad discrete activities involving Congress through its committees, the administration, the research and service communities, and individual program managers. At the level of Congress and the administration, the annual budget is the only plan. Budget decisions are largely incremental, and the most important single factor in determining a current budget is the last year's budget. Exceptions are relatively rare and reflect either major policy issues (such as drug abuse or AIDS) or the specific concerns of key individuals in Congress or the administration.

The budgeting process involves relatively few discussions of trade-offs between programs, especially between programs of different types. The only cross-agency comparison mentioned by any of the individuals interviewed for the planning and priority-setting analyses in this study was a general statement that every effort is made to balance the research increases of NIH and ADAMHA. At no level of budget review, above the programs themselves, was there evidence of an analytic or fact-driven approach to determining resource allocations.

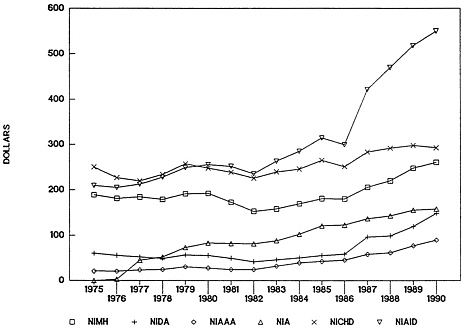

The functional analysis of this subject found that “the budget planning and review process treats research separately from services (block grants, for example) and, in that process, NIH and ADAMHA research programs are treated similarly by the Assistant Secretary's Office and the Department. With regard to budget increases, it is a de facto PHS policy to treat the research programs of ADAMHA and IH similarly” 10(see Figure 4-10 ). Most differences in the final appropriations for the various institutes reflect congressional interests and the effectiveness of various constituency groups.

There is no separate health policy or plan at the DHHS or PHS level to guide the preparation of the budget or to set mutually agreed-upon directions. Planning and budgeting operates on a program-by-program basis. Budget requests are considered in the light of a program' s past history and accomplishments and the effects of infla-

FIGURE 4-10 National Institutes of Health and Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration obligations for research, selected institutes, in constant dollars. Abbreviations: NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health; NIDA, National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse; NIA, National Institute on Aging; NICHD, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: R. Walkington, “Allocations in the Public Health Service,” paper prepared for the IOM Committee on Co-Administration of Service and Research Programs of the NIH, ADAMHA, and Related Agencies, 1991; adapted from information provided by the NIH and ADAMHA budget offices.

tion. Little consideration is likely to be given to the relationship between programs, and comparisons among programs rarely occur. Programs of different types are normally not considered as alternate answers to multifaceted problems; alternative allocation of resources based on a greater ability to solve a problem is seldom considered.

No evidence could be found of trade-offs between the NIH and ADAMHA research budgets or between the research and service budgets within the PHS. For example, discussions at the level of the Assistant Secretary 's and Secretary's offices will tend to focus on one program, such as the maternal and child health block grant program

in HRSA, and then turn to another HRSA program, community and migrant health centers. It is unlikely that the discussions will include careful consideration of whether increasing the maternal and child health block grant in HRSA or increasing the research funds at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) would have a greater impact on infant mortality. Nor is consideration likely to be given to relationships among child development programs such as the research programs of NICHD in NIH, the mental health service development programs of NIMH, and the financing programs of HCFA.

The following statement, while referring to the establishment of a congressional budget, is a realistic description of the entire process:

The final budget resolution is a patchwork compromise of the views of all who participate in the budget process—the different parts of government, the press, the public policy community (think tanks, commentators, former officials), the lobbyists representing a multitude of interests. The final budget's form reflects the deals cut within the executive branch, among the congressional representatives of diverse constituencies, and between the Congress and the administration. Rarely do the January budget and the final resolution match. To understand the budget process is therefore to understand that the budget economies and politics of any federal effort are inextricably entwined, for the budget is fundamentally a political statement. 11

Within PHS Agencies

The various PHS agencies that are addressed in this study (NIH, ADAMHA, and HRSA) differ significantly in their approaches to planning and budgeting. While there are many reasons for these differences, such as history, mission, and leadership, the appropriation structure appears to have a significant effect on the relationships between the agencies and their organizational components. To a much greater degree than in ADAMHA or HRSA, planning and budgeting in NIH is initiated at the institute level and then consolidated at the agency level. Because its mission is research oriented, congressional decisions to increase or decrease health care financing or services-related budgets are largely irrelevant to NIH concerns.

Strategic planning for science has been important in many NIH institutes. Many of the institutes use selected portions of their

strategic plans to contribute to agency and PHS plans and to guide preparation of budgets. Strategic planning has functioned more effectively in institutes with an established knowledge base and stable mission (e.g., the National Eye Institute [NEI], NIDR) than in institutes where the science is in a state of flux (e.g., the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID]) or in an agency such as HRSA where both the science base and agency mission are subject to dispute. 12NEI's strategic plan is an example of a structured, ordered planning and priority-setting process:

This five-year plan will be the latest in a series of national vision research plans that began in 1974 and have been updated at roughly three- to five-year intervals as a joint effort of the [Advisory] Council, the NEI staff, and leading representatives of the vision research community. Among their many uses, the Plans have served the Council in its oversight of the NEI program and provided the NEI staff a guide for day-to-day management as well as long-range forecasting of the appropriate level of federal support for vision research. 13

NIAID, by contrast, is in a state of evolution and conducts only short-term tactical planning. This appears to reflect a realistic response to a rapidly changing and developing field of research. ADAMHA's budgeting and planning process recognizes that the agency is unique in its mix of research and services development and demonstration programs. ADAMHA's budget attempts to implement the concept of an integrated mission, in which progress depends on linking (1) research, (2) treatment, (3) prevention, and (4) national leadership and advocacy and which relies on the notion of program balance rather than trade-offs among alternatives. This balancing act is made somewhat easier by the recent unwritten but widely understood PHS policy that ADAMHA and NIH research budgets will be treated similarly. In a sense, ADAMHA research is protected by this policy. 14

The FY 1992 preliminary budget presentation of ADAMHA to DHHS, for example, makes the following points:

Striking what we believe to be the appropriate balance between expansion of research activities and the need to expand and improve treatment capability . . . [l]inking treatment improvement programs and Office for Substance Abuse Prevention (OSAP) prevention programs to studies of the research institutes, using categorical grants to test hypotheses through field trials. 15

Historically, however, ADAMHA's budget has been driven by the political perception of the importance of the social problems underlying its programs. The early growth of its mental health program was the result of dismantling the archaic state hospital structure. Its more recent growth is driven by perceptions of problems arising from substance abuse and AIDS. In both cases, budget growth was triggered by presidential and congressional needs for visible action.

ADAMHA yearly budgets, unlike those of NIH, are prepared and sent forward as a package, grouped according to goals determined by the ADAMHA administrator, senior staff, and institute leadership. However, no evidence could be found that long-term strategic planning is used in ADAMHA or HRSA as a major planning tool. Instead, as was noted in planning, priority-setting, and budgeting analyses conducted for the committee, planning proceeds differently:

Planning in the Office of the ADAMHA Administrator and within institutes or their equivalents has been integrated in recent years with the budget process. The integration has the advantage of making planning more relevant since it is directly tied to the resources needed for implementation. It also has the advantage of making budget documents more cohesive. The negative side of this integration is that planning may acquire some of the characteristics of the budget process: fragmentation, short-range orientation, and the need to mirror current administration policy including shifts in focus. While the integration is too new to assess, an early impression is that the benefits accrue to the budget process more than to the planning process. 16

HRSA, the newest of the major PHS agencies, was created in 1982 and has had a difficult time in articulating its mission, which includes a wide range of disparate activities and discrete programs. The planning process in HRSA is centralized, in that regard more like ADAMHA' s planning process than NIH's. Budgeting, however, tends to be program specific rather than thematic and goal oriented as in ADAMHA. The focus of HRSA's current planning activities, as its budgeting process, is to develop a comprehensive agency mission and increase linkages with other PHS agencies.

Based on interviews in HRSA and ADAMHA, the planning processes in these agencies appear less ordered, and linkages with agency and PHS plans less structured, than in NIH. Although institute planning processes within ADAMHA appear admirably flexible, “with continuing review and revision as circumstances

dictate,” 17 a number of current science administrators and policy analysts pointed out that flexibility also allows the planning process to be subject to frequent changes of direction and focus. Plans that have been developed at the institute or bureau level often appear to have been prepared in an ad hoc manner and are frequently disregarded. As a result, they fail to provide continuity of direction and focus to institute and bureau programs, as they have in NIH. 18The committee recommends that all agencies within the PHS and each research institute be mandated to develop five-year plans, the process for which shall be reviewed by the Assistant Secretary for Health, and that plans be updated (with changes only) on a yearly basis. The committee notes that it is as important that five-year plans specify program goals and objectives as that they be linked with and revised according to an annual budget.

In summary, each of the three agencies discussed above has a very different management style and organizational ethos:

-

NIH is scientific, collegial, and consensual, with the role of individual institutes highlighted.

-

ADAMHA is centralized and thematic with the roles of individual institutes deemphasized.

-

HRSA, which has been administratively centralized but programmatically disparate, is attempting to integrate its programs thematically.

EFFECTIVENESS OF DEMONSTRATION AND INFORMATION DISSEMINATION PROGRAMS

The committee understands information dissemination and knowledge transfer to be the process by which the results of biomedical and behavioral research are moved from their creation to their application in clinical practice (i.e., new knowledge into new practices) through applied research, clinical education and training, and demonstrations. The committee wanted to know whether, within a single agency such as ADAMHA, there were fewer obstacles to the translation of research findings into service programs.

As described earlier, within the ADAMHA model of the so-called research –services continuum, more than in other models, demonstrations provide a theoretical link between the findings of clinical research and the introduction of innovations into the structure and delivery of services. 19However, few of the models include replication

of demonstrations in multiple sites (a critical component of any evaluation of the effectiveness of the new technology or knowledge being “demonstrated”). The case studies revealed that very little funding was available specifically for replication of demonstrations, and very little if any replication was being carried out. In addition, epidemiologic research and education and training (which has been noted in previous studies to be indirectly related to technology transfer) are completely omitted from the models. For several years in the 1980s, after the majority of demonstration programs were consolidated under the block grant program, ADAMHA administered no demonstrations at all. Most of the other demonstration programs in the PHS are administered by HRSA. Demonstration programs are also administered in other parts of DHHS (for example, the Office of Human Development Services [OHDS], the Family Support Administration [FSA], and the Health Care Financing Administration [HCFA]).

Within ADAMHA and elsewhere in the PHS, research and service demonstrations serve different functions; in most instances within ADAMHA they are administered by different organizational units. Four types of demonstrations were identified:

-

Research demonstrations are hypothesis-driven demonstrations based on previous basic and applied research. They employ experimental or quasi-experimental designs (including either control groups or comparison groups) to develop, test, and foster the application of existing knowledge gained from basic and clinical research for the control of categorical diseases or behavioral dysfunctions. Research demonstrations may also evaluate the feasibility, productivity, or outcomes of treatment approaches in community-based settings. Use of research demonstrations as a method for testing treatment models is consistent with the scientific research focus of the other major activities of research institutes.

-

Service demonstrations, on the other hand, focus on demonstrating the ability to develop and provide a set of new services targeting a specific population or disease. In contrast to research demonstrations, service demonstrations are not typically hypothesis driven, nor do they employ comparison or control groups. However, service demonstrations most often include (or should include) either process or outcome evaluations or both. Service demonstrations, if properly evaluated, can be a first step in development of community-based models that later can be rigorously tested as research demonstrations.

-

Technology introduction or treatment diffusion demonstrations at present have been defined as part of the research–services continuum only by OTI. Such demonstrations are designed to replicate successful demonstrations across multiple sites to establish the feasibility of broad implementation of models and to evaluate costs and benefits in a variety of settings.

-

Services systems development demonstrations are often used to build services capacity in states and localities. The funds provided through these demonstrations can act as a catalyst or provide an incentive for making programmatic changes at state and local levels that would not be possible without this funding.

The relationship between health services research and these types of demonstrations differs. For the demonstrations to achieve the goals described above, however, some form of collaboration among clinical research, health services research, and the structure and delivery of services is critical. For example, if costs, effectiveness, and efficiency of demonstrations or the feasibility of broad dissemination is to be analyzed prior to implementation and national dissemination, decisions about research design need to be made at the outset of demonstrations. With regard to evaluation of effectiveness and outcomes of services demonstrations, a different level of collaboration may be critical to the outcome. As noted in the background paper prepared for the committee's analyses of health services research programs:

There is general recognition that the research component within demonstrations differs as one moves from research demonstrations to treatment diffusion demonstrations and services delivery. This view has led some to suggest that health services research and research demonstrations should be co-administered and that treatment diffusion and services demonstrations that include a health services research component should be co-administered with programs related to the structure and delivery of health care services. 20

The committee's analyses also pointed out that both within and outside government, health services research needs strong links to research settings and to the services community.

Conflicting expectations on the part of Congress and federal agencies have created a number of difficulties in administration of demonstration programs. Congress has not fully appreciated the differences in the functions of demonstrations, “routinely viewing

demonstrations simply as a disguised form of service.” 21 Interviews conducted for an evaluation of demonstration activities in ADAMHA, NIH, and HRSA suggest that one result of this view is a failure to replicate successful demonstrations across multiple sites prior to implementation; another result is the subsequent failure to evaluate the effectiveness of implementation prior to national dissemination. The case study of substance-abusing pregnant women, for example, raised important questions about the transfer of demonstration results into community settings without due attention to evaluations of costs and staffing arrangements. Another illustration of this same point is that until early in 1991, no evaluation component was considered for service demonstration projects funded by OSAP. A number of federal officials have suggested that there is a need for better articulation of the different types of demonstrations and of the appropriateness of translating a demonstration into an operating program. Analyses of many demonstration programs conducted for this study found evidence that the management of demonstration programs has been hampered by differences in agency and congressional objectives. For example, a second cycle of research demonstration grants for an ADAMHA institute was funded by Congress before the first was complete, thus preventing the results of the first cycle from being used to inform the second. In addition, instability in funding for demonstrations seems to have made long-range planning for demonstration programs almost impossible. Interviews conducted for this study indicated that the amount of funds available for replication of demonstrations and evaluation of their implementation affect whether new practices and systems innovations will be disseminated appropriately—that is, after having been shown to be cost-effective and efficacious. The committee recommends that replication, which is vital to basic and clinical research but which has not been considered a central element of most demonstrations, be ensured in new and ongoing research demonstrations following single-site experiments and prior to implementation and national dissemination.

In the ADAMHA and OTI models of the research–services continuum, as well as in the health care system in general, the block grant program serves as an important focal point for the transfer of demonstration results into the structure and delivery of services. Since 1981, virtually all funding for service development programs has been provided through the ADMS block grant program (small exceptions are the CSP and CASSP programs in NIMH). As discussed in Chapter 2, the change to block grants statutorily limited agency involvement in health services and demonstrations, which devolved to

the states. Although Congress seemed to have wanted a larger federal role in the block grant program in the 1980s, it did not appropriate funds to agencies for the purposes of guiding, shaping, or assessing federally supported state programs. According to ADAMHA administrations, it seemed pointless, at the time, to establish structures without resources. The focus of ADAMHA institutes shifted away from services development programs toward biomedical research, as did the focus of the entire agency. In addition, data collection requirements (previously mandated for states to receive federal funds) were eliminated, as was the availability of discretionary funds for services evaluation. “As a result, researchers did not have data, policy planners did not have data, and perhaps most importantly, program administrators . . . did not have data to describe program performance to their political masters.” 22

Discontent with this lack of federal direction and oversight began to surface in Congress by the mid-1980s. Under continued pressure from advocacy groups, Congress has increasingly limited state discretion under block grant programs by mandating setaside requirements for expenditures of funds to target specific populations and health problems (e.g., intravenous drug users, substance-abusing pregnant women, health services for mothers and children, and children with special health care needs). In addition, since 1986, there has been a continuing and massive infusion of funds for service and research demonstrations in ADAMHA and HRSA, targeted at a variety of populations and problems. For some within ADAMHA, the recent infusion of funds for demonstration programs has been viewed as a diversion from the predominant research orientation of the agency. In the last few years, tensions have developed between those who would restrict the mission of the agency to research and those who would create a more integrated agency structure that encompasses research, prevention, and services development and demonstration programs.

A number of officials in ADAMHA, HRSA, and CDC feel that state allocations of block grant funds not only could but should be used to continue the service portion of successful demonstrations and to serve as the means for introducing innovations. However, until 1988, the structure of the block grant system inhibited this process by minimizing the federal role in promoting services innovations. According to program administrators in ADAMHA and CDC, there is no formal link between demonstration and block grant programs funded by those agencies, although many demonstration programs are administered by the same state agencies that administer the block grant program. To ensure that the programmatic objectives of

demonstrations are achieved, the committee recommends that a research program be initiated within the PHS to determine effective dissemination mechanisms for demonstrations and the results of health services research.

Interviews with constituency groups noted that state agency officials often are unaware of the existence of federal demonstration projects in their states, particularly those funded by ADAMHA institutes and offices. The Bureau of Maternal and Child Health in HRSA has a long history of collaborating with and consulting states with regard to demonstration projects. Interviews conducted for the committee revealed that this collaboration has increased the potential of demonstrations being focused on high-priority health problems in each state and has ensured that states are knowledgeable about proposed maternal and child health projects. In ADAMHA demonstration projects, however, such consultation and collaboration with states are less likely to be uniformly incorporated into the application process. In many instances state agencies have been reluctant to appropriate the funds to continue demonstrations, even successful ones, after federal funding is ended. A plan that includes incentives for translating successful demonstration findings into the structure and delivery of services should be accompanied by opportunities for state review and comment on all types of federal demonstration applications. Potential sources of postdemonstration funding for successful demonstrations (i.e., federal, state, local, and private sources) should be explored prior to initiating a demonstration project.

One of the important questions raised in the case studies conducted for this study was how to shorten the time between the “production ” of research findings from basic research and their applications in applied research. In fact, the case study of substance-abusing pregnant women raised serious questions about the lag between findings in basic research (about the effects on pregnant women of alcohol and cocaine) and federal funding of studies on clinical interventions. None of the case study analyses found specific mechanisms in place for identifying the emerging results of clinical research or demonstrations that might serve as a basis for initiating intervention trials. The case studies of substance-abusing pregnant women and schizophrenia found no evidence of established mechanisms for identifying demonstration or other research results appropriate for dissemination and introduction into state programs through the block grant program. In the absence of established policies or mechanisms, program administrators at one ADAMHA institute initiated a campaign to encourage state agency directors receiving block

grant funds to support the service delivery costs associated with demonstrations.

With only one exception (the model developed by OTI), none of the models of the research–services continuum from the NIH institutes or ADAMHA refers to the specific mechanisms required to move research findings through demonstrations to evaluation, introduction, and implementation. Although the theoretical models developed in NIH, ADAMHA, and OTI are useful, they are difficult to implement. As Beryl Radin points out in her background paper on linkages between research and service programs in federal agencies, “even when an agency is convinced that it has developed an understanding of an issue through demonstration programs and/or evaluations, there is significant evidence that the diversity of decision settings and populations within the United States makes it difficult to think of simple dissemination of findings.” 23 The organizational structure that exists in ADAMHA does not seem, by itself, to foster more rapid or improved dissemination.

In 1988, ADAMHA was authorized to set aside between 5 and 15 percent of the total ADMS block grant allocation to be used for data collection, health services research, and technical assistance to states and localities. This marked a significant shift in federal participation in the block grant program, allowing ADAMHA to begin rebuilding some national analytical capacities. Throughout the 1980s, states were free to evolve their own systems for data collection, systems that are not necessarily compatible with the goal of producing accurate or meaningful national statistics. As noted in a background paper on PHS block grants, congressional legislation in the early 1980s in effect dismantled the data collection systems that had existed under categorical programs, and members of Congress seemed unaware that the effect was to leave federal agencies without information about how federal allocations were being used by states and localities.

Setaside funds are currently available from the ADMS block grant for data collection, health services research, and technical assistance. However, analyses conducted for this study pointed out that the activities supported by the setaside did not seem to be directly tied to the objectives or the administration of the block grant program. A number of federal officials interviewed for this study felt that setaside funds could and should be used (1) to evaluate the feasibility of implementing interventions that have been proved successful in single-site demonstrations in other sites and conditions, (2) to facilitate data collection by the states related to the objectives of the block grant program, and (3) to provide technical assistance to states

and localities necessary for introducing innovations into the structure and delivery of health care services.

With the creation of OTI and a shift toward planning in block grant administration, increased attention is being paid to the technical assistance needs of states in the development of adequate data collection systems. If OTI is to carry out its tasks effectively, however, new and unfamiliar administrative mechanisms may need to be put in place to allow for negotiation across unit boundaries. For example, ensuring that data collection is not duplicative or inappropriate is likely to require central planning and coordinative strategies. Yet none of the case studies or interviews conducted for this study could establish the existence of specific mechanisms or leadership strategies for moving successful services demonstrations from one unit into research demonstrations carried out in the institutes and, subsequently, into a unit responsible for applications and implementation. The case study of substance-abusing pregnant women, for example, noted that in the absence of such mechanisms the “potential for duplication of efforts among the many different services demonstrations is present. ” 24 Although ADAMHA is also responsible for block grant services and for prevention programs for substance-abusing pregnant women, the Office of the Administrator did not appear to have provided policy direction to such efforts.

It was suggested in many interviews with current administrators and grantees that the skills necessary for the effective management of research and service programs are quite different. The research process requires time and autonomy, for which one set of management skills is appropriate. But social and political pressure for immediate results (for problems such as substance abuse) may require targeted efforts to facilitate movement from clinical research to demonstrations and, ultimately, to national dissemination, for which quite another set of skills are needed. Technical assistance and program development require not only another set of management skills but also an understanding of needs assessment, the organization and staffing of clinical programs, financing and reimbursement, and staff development. And because of differences in the level of training of those responsible for providing care at the local level, federally funded service development or demonstration programs are likely to require yet another set of specialized skills and knowledge.

Information dissemination activities commonly cited in interviews for this study include publication in scientific journals, creation of national clearinghouses and telephone information lines, and conferences for health care professionals and constituency groups. In most institutes these activities are well administered. It was suggested in

a number of the interviews with constituency groups, however, that the clearinghouse approach (cataloging information about innovative demonstrations) may make it difficult for users to distinguish between successful and less successful demonstration results. In addition, the case study of substance-abusing pregnant women, as well as analyses of information dissemination activities, suggests that current dissemination activities may be insufficient to promote the use of many new clinical practices or systems innovations.

Articles in scientific journals targeted to researchers may not meet the needs of all those who use research findings. Previous analyses, as well as the committee's case studies, found that the characteristics of individuals and organizations using new practices heavily affect how the results of research are received and used. For instance, nontraditional service providers may require access to training, technical manuals, or technical assistance in order to be able to adopt the results of successful demonstrations. The committee also believes that there are areas in which technical assistance and clinical training are needed if demonstration results are to be effectively disseminated to state and local programs. The committee therefore recommends that the responsibility for technical assistance and clinical training programs of professionals and nonprofessionals (and the resources to carry them out) be part of the explicit mission of agencies that fund and administer operating programs (e.g., HRSA, the Indian Health Service, and ADAMHA).

ORGANIZATIONAL CAPACITY AND PROGRAM PLACEMENT

In the course of gathering information and deliberating on the central issue of this study, the committee reached other conclusions closely related to its primary charge. Analyses of these issues and recommendations are included here as an adjunct to the report. For example, the case study of substance-abusing pregnant women raised serious questions about how decisions are made regarding where to locate programs within the PHS. As noted earlier, analyses of block grant and demonstration programs and of planning and budgeting processes also raised a number of concerns about the effects of frequent movement of programs.

The extraordinary growth in demonstration and block grant funds (particularly for drug treatment) in the past several years has resulted in some increase in organizational differentiation—that is,

separate offices and institutes handling prevention, block grant activities, and research within ADAMHA. On the other hand, the case study of substance-abusing pregnant women suggests that these differentiated organizational units (e.g., OSAP) have had problems in developing the infrastructure necessary to keep pace with the rapid growth of funds. The implementation of some federal programs may be unsuccessful because political agreement about their objectives has never been obtained, funding is not obtained, or political strategies are ill conceived. Other programs may founder because federal organizations fail to develop the necessary organizational capacity to produce results, or because they give insufficient attention to the consequences to the organization as a whole of creating new capacity. The complexity and shifting nature of tasks and programs may call for specialized units with the capacity for discretionary functioning within an agency or institute. It was difficult to determine with assurance the extent to which these difficulties are related to a lack of political consensus about the programs, to inadequate attention to organizational development, or to leadership problems at the office or agency level. It is most likely to be some combination of all three.

The successful implementation of new or greatly expanded programs may entail significant change in standard operating procedures or in the very “culture” of the existing organization and its units. For example, the creation of a new organizational unit within the Office of the Administrator (OTI, and before it, OSAP) gave ADAMHA a new organizational capacity to administer treatment improvement and preventive services and services demonstrations. As noted in the case study of substance-abusing pregnant women and in the analyses of planning, priority setting, and budgeting, the creation of OTI has usefully increased functional specialization within ADAMHA.

Interviews with constituency groups also suggested that specialized organizational arrangements are important because they provide a focal point for group efforts by bringing visibility, expertise, and a concentration of resources to a specific disease or problem. In several interviews, constituency groups questioned the rationale for placement of programs within specific PHS agencies. There was some indication, however, that these arrangements had more of an effect on constituency groups with interests in a substantive area than on those with interests in cross-cutting issues such as science policy.

Specialization comes with a price. Interviews conducted with constituency groups suggest that the creation of new organizational capacity, such as the Center for Medical Effectiveness Research (CMER) in the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research and OTI, has resulted in the need for coordination of programmatic objectives.

As pointed out in the case studies, in the report of the task force on health services research, and in interviews with current administrators of block grant and demonstration programs, the different administrative requirements of research and service programs often result in conflicting priorities that require negotiation and mediation at the most senior agency levels.

Co-location does not guarantee, by itself, any specific relationship between research and service development or delivery programs. Each of the case studies underscores the need for federal executives to understand not only the shared characteristics but also the lines of division, suspicion, and rivalry among organizational units involved in a common effort. Interviews for analyses of block grant and demonstration programs and the case study of schizophrenia reveal a variety of differences, jealousies, and lack of clarity about overlapping responsibilities across organizational units within ADAMHA as it has grown and expanded its scope. In another area, the case study of schizophrenia also points out that a shift in leadership within an institute brought with it a change in the focus of research efforts, resulting in significant rivalry among divisions. Interviews conducted for the case study of Alzheimer's disease point out similar rivalries when a significant number of institutes are responsible for research programs related to the same disease.