3

PTSD Programs and Services in the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs

Both ansnumerous Affairs the Department programs (VA) have of comprehensive and Defense services (DoD) designed health and the careto Department prevent, systems thatscreen of include Veter- for, diagnose, and treat for PTSD, and to rehabilitate service members and veterans who have or are at risk for PTSD. Many of the programs and services are under different commands and authorities in the departments, which make it difficult to identify and evaluate them. This is particularly true for DoD, where various mental health programs are under the authority of the DoD central office and dispersed across the service branches, installation commanders, and medical commanders. In VA, policy and oversight for PTSD programs are managed from the central office, but regional and local health care directors have responsibility for day-to-day operations and program or service innovations.

DoD and VA have acknowledged the need for a more integrated approach to mental health care and, in 2011, began development of the collaborative DoD/VA Integrated Mental Health Strategy (IMHS) (DoD/VA, 2011). The strategy uses a public health model to improve DoD and VA mental health care for all active-duty service members, National Guard and reserve component members, veterans, and their families. The IMHS has four strategic goals: expand access to mental health care in DoD and VA; ensure quality and continuity of care across the departments; advance care through community partnership, education, and successful public communication; and promote resilience and build better mental health care systems. According to the strategy, these goals are to be achieved within 3 years by developing and implementing 28 strategic actions. The strate-

gic goals will include both operating plans and performance metrics. The IMHS is a good beginning to a comprehensive approach to better mental health management in the departments, but it is not PTSD-specific. There is also a lack of information on whether the strategy has been implemented across DoD and VA and what progress has been made on achieving the goals and the strategic actions, to date.

In this chapter, the organizational structure of the mental health care systems in DoD and VA are briefly described. The chapter then presents various programs and services for PTSD that are available in DoD and VA, with particular emphasis on PTSD programs that are available to service members at Fort Hood and Fort Bliss, Texas, and at Fort Campbell, Tennessee (as required by the committee’s statement of task). Where data are available on the effectiveness of a program, this information is noted. The chapter concludes with a summary of DoD and VA PTSD or mental health program evaluations that are being, or have recently been, conducted by the departments or by other organizations.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

DoD has worked to prevent, diagnose, and treat for PTSD for many years. PTSD-related or -focused services are offered at military treatment facilities (MTFs), embedded mental health clinics, and primary care clinics. Responsibility for developing, implementing, and evaluating PTSD programs and services resides in several offices in DoD and the service branches. The next section provides an overview of the organization of the DoD health care system followed by a description of the prevention programs, screening and diagnostic assessments, and treatment and rehabilitation programs that are available to service members. This section also includes descriptions of PTSD programs that are available in the community if they treat a large number of service members or provide a service that is not available on the military installation.

Organization

Overseen by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs [OASD(HA)], the military health system (MHS) is responsible for maintaining the readiness of military personnel by promoting physical and mental fitness, providing emergency and long-term casualty care, and ensuring the delivery of health care to all service members, retirees, and their families. MHS coordinates efforts of the medical departments of the Army, Navy (includes the Marine Corps), and Air Force; the joint chiefs of staff; the combatant command surgeons; and private-sector health care providers,

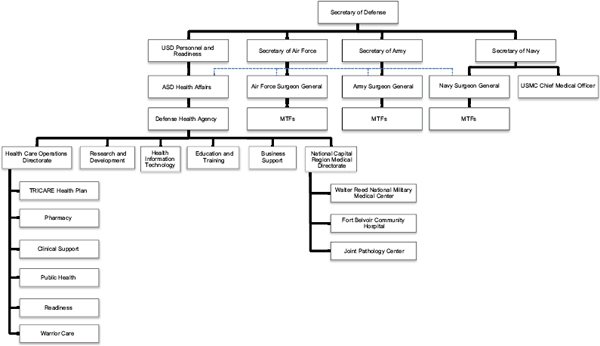

hospitals, and pharmacies. Figure 3-1 shows the organizational structure of the major health care components in DoD.

How mental health care is provided within DoD varies greatly among its service branches. Mental health care is provided to service members in garrison primarily in MTFs and affiliated mental health clinics that are on or near military bases. The affiliated mental health clinics operate under the direction of regional Army or Navy medical commands of the military departments or Air Force air-base wing commanders. The Navy provides the majority of mental health service to the Marine Corps. Because each installation has its own unique arrangement of medical facilities—including hospitals, clinics, dispensaries, and aid stations—it is not possible to make generalizations regarding the availability of facilities on each installation. Many military facilities are now under joint commands, for example, Joint Base Langley-Eustis (Air Force and Army).

A large component of the MHS is the TRICARE network. Although TRICARE is sometimes used to describe only purchased care, the committee uses the term in a broader sense: as a wide-reaching health care provider for DoD beneficiaries that includes service members, retirees, and their families and delivers direct care through MTFs and purchased care through network and non-network civilian health professionals, hospitals, and pharmacies (TRICARE Management Activity, 2013). The DoD TRICARE Management Activity contracts with community purchased care providers when direct care providers are not available or supplemental service is required. In 2013, it is estimated that about 9.66 million beneficiaries1 were eligible for DoD medical care—15.2% were active-duty service members and 3.7% were members of the National Guard or reserves—and 5.5 million beneficiaries were enrolled in TRICARE. According to TRICARE Management Activity, a network of 56 hospitals and medical centers and 361 ambulatory health clinics provide direct care in the MHS, and more than 3,300 network acute-care hospitals and 914 behavioral health facilities provide purchased care (TRICARE Management Activity, 2013).

The organization of health care services, as depicted in Figure 3-1, provides a sense of where PTSD management services reside in the department and the service branches. PTSD management programs and services are implemented by each service branch, and by the OASD(HA) through its management of the TRICARE contract programs. Both the OASD(HA) and the service branches have issued policy directives and instructions that pertain to the prevention of, assessment of, treatment for, or management of PTSD, such as ASD(HA) memorandum “Clinical Policy Guidance for

________________

1 Beneficiaries include sponsors (active-duty, retired, and National Guard and reserve members) and family members (spouses and children who are registered in the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System); in some situations, other people may be considered beneficiaries.

FIGURE 3-1 Organization of health care services provided by DoD in the continental United States. Health care in theater is under a different command structure from that in garrison and is not included in this figure. The OASD(HA) oversees force health protection and readiness programs and the Defense Health Agency. It has an administrative and policy relationship to the MTFs, which report to the surgeon general for each service branch. All medical facilities in the national capital region of Washington, DC, regardless of the service branch to which they belong, are under the jurisdiction of the Defense Health Agency. NOTE: ASD = Assistant Secretary of Defense; MTF = military treatment facility; USD = Under Secretary of Defense; USMC = U.S. Marine Corps.

Assessment and Treatment of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder” (August 24, 2012) and DoD Instruction 6490.09, “Directors of Psychological Health” (February 2, 2012). Many of these policies have been implemented recently or are in the process of being implemented, so compliance with them and their effects on improving PTSD management have not yet been assessed.

Prevention Programs

Each service branch has developed and implemented training, services, and programs intended to foster mental resilience and to preserve mission readiness and effectiveness, and mitigate adverse consequences of exposure to stress (DoD, 2011b), but none is PTSD-specific. While there is overlap in the goals of these programs, the content of each one is tailored to a particular service branch.

Army

Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness (CSF2) is a resilience-building program designed to enhance the performance of soldiers, their families, and Army civilians. CSF2 has five dimensions—physical, emotional, social, family, and spiritual—and consists of four components: master resilience training, comprehensive resilience modules, the global assessment tool, and the Army Center for Enhanced Performance (U.S. Army, 2012b; Weinick et al., 2011). The master resilience training for noncommissioned officers and midlevel supervisors is a “train the trainer” model, in which master resilience trainers pass on lessons from their training to the soldiers in their units. The effectiveness of this program is discussed in Chapter 7.

Navy and Marine Corps

The foundation for psychological health promotion and mental disorder prevention in both the Navy and Marine Corps is their Combat and Operational Stress Control (COSC) Program, in which unit leaders are directly responsible for protecting the mental health of their service members and families (Marine Corps Combat Development Command and Navy Warfare Development Command, 2010; Nash, 2011). Navy–Marine Corps COSC trains leaders to use three tools for assessing and promoting mental health: the “stress-continuum model” (a color-coded tool for identifying levels of stress and discriminating normative from at-risk stress states), five “core leader functions” (strengthen, mitigate, identify, treat, and reintegrate), and Combat and Operational Stress First Aid, a military-specific version of psychological first aid for early, preclinical management of acute stress (Nash and Watson, 2012).

The Marine Corps developed the Operational Stress Control and Readiness (OSCAR) program as a means to disseminate Navy–Marine Corps COSC principles and practices throughout its operating forces. OSCAR is intended to prevent, identify, and manage stress reactions at the level of operational units through two simultaneous efforts: training OSCAR mentors (small-unit leaders) and extenders (chaplains, corpsmen, and non-mental-health medical providers). OSCAR mentors and extenders monitor and manage the stress of unit members by using the COSC tools and embedding OSCAR providers (mental health professionals) directly in combat units throughout their deployment cycles to provide clinical support (Nash, 2006).

Air Force

In 2008, the Air Force began Airmen Resilience Training to enhance resilience, increase recognition of stress symptoms, and connect airmen with information on when, how, and where to access mental health and other support services. It has predeployment and postdeployment reintegration education components that all airmen are required to take, and a master resiliency training component, similar to that of the Army’s CSF2 program (U.S. Air Force, 2012a; Weinick et al., 2011). The Air Force requires that all its installations have traumatic stress response teams to offer resilience education for those likely to experience traumatic events, followed by education, intervention, screening, psychological first aid, and referral as necessary (U.S. Air Force, 2006). Exposed airmen can seek up to four one-on-one education and consultation meetings with a team member. The meetings, however, are not considered to be treatment for exposure to a traumatic event and, therefore, often are not documented.

Screening and Diagnosis Services

DoD has a series of screenings and assessments for mental health during the deployment cycle for all service members—the pre-deployment health assessment, the post-deployment health assessment (PDHA), and the post-deployment health reassessment (PDHRA) (DoD, 2011a). The predeployment health assessment is administered within 60 days before deployment and documents general health information on each service member. There is only one mental health question: “During the past year, have you sought counseling or care for your mental health?” As noted in the phase 1 report, this question is of questionable usefulness for the assessment of predeployment mental health concerns. An affirmative response to the question may result in referral to a medical provider for further assessment for deployment.

The PDHA is given to service members within 30 days after they leave their assigned posts or after their return from deployment and the PDHRA is administered 3–6 months after return from deployment. Both the PDHA and the PDHRA ask the same four standardized questions related to PTSD symptoms. On the basis of responses to the questions, a service member may be referred for further evaluation (GAO, 2008). Each service has its own process for administering the assessments. For example, the Marine Corps administers the PDHA and the PDHRA in deployment health clinics along with other screening tools, such as automated neuropsychological assessment metrics for traumatic brain injury. As noted in the phase 1 report, symptoms of PTSD may be underreported on the PDHA and PDHRA, and as a result, the true prevalence of PTSD in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) veterans may be higher than estimated.

Not everyone who is given a referral seeks treatment; 32% of those who receive referrals for outpatient mental health care do not activate them (Dinneen, 2011). As of the first quarter of 2010, data indicate that about 65% of those referred for mental health consultations actually received treatment (Dinneen, 2011). Updated information on the number of mental health referrals that get activated was requested from DoD but was not received for this report. At a visit to a Marine Corps base, the committee heard that 59% of all mental health referrals were activated, compared with 78% of referrals for traumatic brain injury (TBI), 83% for substance abuse, and 77% for neurological problems.

Treatment Programs and Services

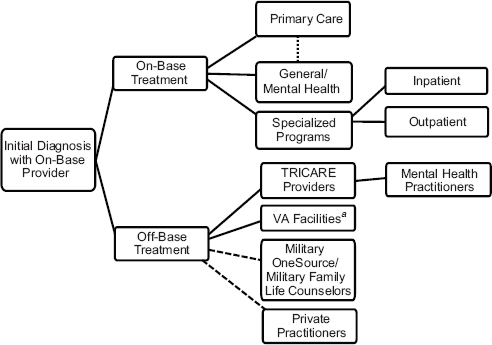

Although early interventions for stress management may occur while a service member is serving in theater, most PTSD treatment is delivered in garrison, on and off base. In addition, most treatment for PTSD is outpatient and occurs in general mental health clinics or primary care settings. Figure 3-2 illustrates the treatment pathways available to service members who have PTSD. For example, service members who have mild symptoms or subsyndromal PTSD may be treated in primary care clinics. DoD has adopted the patient-centered medical home model (PCMH) to provide mental health services in primary care settings to improve patient access to mental health care, provide coordinated care for comorbidities, and decrease overall health costs (DoD, 2013a; TRICARE Management Activity, 2013). The PCMH also provides a mechanism for primary care sites to receive patients back from specialty mental health care and to coordinate maintenance treatment with mental health and rehabilitative services. Case facilitators assist primary care clinicians with follow-up, symptom monitoring, and treatment adjustment (medication, counseling, or both) (Engel et al., 2008).

FIGURE 3-2 PTSD treatment pathways available in DoD. Dotted line between primary care and general mental health denotes that many service branches are moving to the PCMH model in which mental health practitioners are embedded in primary care teams. On-base providers may recommend that some service members seek counseling from Military OneSource and MFLC counseling for co-occuring conditions such as relationship problems, although a referral is not required to seek that counseling. Service members who seek care from private practitioners who are not part of the TRICARE network do not need a referral from an on-base provider.

a Treatment for active-duty service members in VA facilities is rare, but it is an option in some locations.

The Army, Air Force, and Marines are all implementing some form of integrated mental health care. The Army’s Re-engineering Systems for Primary Care Treatment of Depression and PTSD in the Military (RESPECT-Mil) model of integrating mental health care in primary care settings has been replaced by a PCMH network of over 40 embedded behavioral health clinics that support combat brigades, expand intensive outpatient programs, and standardize case management (U.S. Army, 2013b). The Air Force Behavioral Health Optimization Program also integrates mental health and primary care services to reduce stigma and enhance access to mental health care (DoD, 2013b; U.S. Air Force, 2011). The Navy is integrating mental health personnel within its Medical Home Port programs, and the Marine-

Centered Medical Home is currently under development with collaboration from the Navy and the Marine Corps deployment health clinics (DoD, 2013b).

In the Army, mental health care providers are in both MTFs and mental health clinics embedded in brigades (3,000–4,000 soldiers). MTFs provide both outpatient and inpatient treatment, whereas embedded clinics are limited to outpatient care. Embedded mental health care providers also serve as advisers to the commanders of their operational units. The Army has established 44 embedded clinics in brigades and plans to establish them service-wide (U.S. Army, 2013a). Embedded health teams consist of 13 providers and staff, including at least one uniformed officer who is a mental health care provider (Blakeley and Jansen, 2013).

Outpatient care for marines and Navy personnel is provided mainly through mental health clinics close to the units, but MTFs also provide some PTSD treatment. OSCAR providers can also treat marines who have PTSD. As full members of the operational units to which they are assigned, OSCAR providers increase access to mental health services in garrison, during training, and during deployment. Marine Corps deployment health clinics also have embedded providers to treat for mild to moderate mental health conditions in a timely manner and thus reduce the need for referrals. During 2005–2012, 5,390 marines had PTSD encounters in primary care clinics, 16,483 had encounters in mental health settings, and 1,496 had encounters in other clinics. Of Navy personnel, 2,714 had PTSD encounters in primary care clinics during 2005–2012, 13,320 had encounters in mental health clinics, and 1,371 had encounters in other clinics (U.S. Navy, 2013). For many years, the Navy has stationed a full-time clinical psychologist on each of its aircraft carriers for the duration of their overseas deployments.

All Air Force MTFs have mental health outpatient clinics. During 2005–2011, 7,028 Air Force personnel who had PTSD were treated in outpatient clinics, 6,413 in specialty mental health clinics, and 3,347 in primary care clinics. Those in the outpatient clinics received an average of 9.4 psychotherapy sessions (range of averages 8.1 sessions in 2005 to 10.9 sessions in 2011); however, 64% of airmen attended seven or fewer psychotherapy sessions (U.S. Air Force, 2012b). The Air Force has mental health care providers in its intelligence and remotely piloted aircraft units as well (U.S. Air Force, 2013).

Each service branch also embeds mental health care providers in especially high-risk units, such as special operations units and units in which personnel are involved in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Although the goals of embedding are to shorten the physical distance between patients and providers, to enhance mutual trust and understanding, and potentially to decrease barriers to care for PTSD, no studies have confirmed

the efficacy or effectiveness of the embedded mental health programs in the service branches.

Service members in need of more intensive PTSD treatment may be referred to a specialized program. There are 21 such programs in DoD: six intensive outpatient programs, eleven partial hospitalization or day treatment programs, and four residential treatment facilities. Intensive outpatient programs operate 3–4 hours per day and 3–5 days per week, and generally run 4–6 weeks. Patients in those programs remain with their units during treatment (O’Toole, 2012). Criteria for admission to these programs are variable; for example, some programs accept patients who have substance use disorder in addition to PTSD and others do not.

Some military installations offer intensive outpatient treatment programs that include evidence-based psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy as recommended in the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress (VA/DoD, 2010), as well as such complementary and alternative therapies as meditation, recreational therapy, and biofeedback. One example of an intensive outpatient PTSD program is the Army Warrior Resilience Center (WRC; originally the Restoration and Resilience Center) at Fort Bliss, Texas. This 4-week, 35-hour/week program treats 3 concurrent cohorts of 10 soldiers who have combat-related PTSD; cohorts are distinguished by medical board evaluation status. Referrals to the WRC generally come from the embedded mental health clinics or the Family Advocacy Program. Participation in the program is voluntary but the soldiers must be willing to try all therapies offered in the program. Every soldier has at least one complementary and alternative therapy session daily to calm down and relax after psychotherapy. WRC also offers family and partner support groups. Patient outcomes are tracked with the PTSD Checklist-Military (PCL-M), Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and a generalized-anxiety disorder assessment tool at entry, midpoint, and completion of the program. WRC offers aftercare services for soldiers who need additional individual or group therapy and has drop-in yoga, art, and meditation classes and spousal support activities. WRC providers reported that when outcomes were tracked in the original Restoration and Resilience Center program, 80% of soldiers planning to return to duty were able to do so, but current numbers were not available. Although the WRC staff reported that they collect data on patient outcomes, they had not published any results.

Another example is the Army Warrior Combat Stress Reset Program at Fort Hood, Texas, which was modeled after the Fort Bliss Restoration and Resilience Center and the Walter Reed Army Medical Center complementary and alternative medicine programs and includes a program evaluation plan. The program consists of 3 weeks of intensive daily treatment for groups of 12 soldiers that uses evidence-based individual therapy; group therapy; acupuncture; relaxation techniques; a variety of complementary

and alternative interventions, such as yoga, meditation, neurofeedback, and cranial electrical stimulation; and occupational therapy. That treatment regimen can be followed by 8 additional weeks of therapy if necessary. The current wait list for the program is about a year, and priority is given to soldiers who want to remain on active duty. Soldiers who have substance use disorders are not eligible for the program and are referred to a dual-diagnosis intensive outpatient program. The PCL-M and depression and anxiety measures are given before and after the program along with patient satisfaction surveys, to measure outcomes and changes in PTSD symptoms (Wesch, 2011), but results have not been published. Although the Reset leaders would like to expand the program to accommodate more soldiers, there is no space available at Fort Hood for them to do so.

Partial hospitalization (programs associated with a hospital) and day treatment programs (programs that are usually outpatient) for PTSD are similar to intensive outpatient programs. They have highly structured environments and activities—similar to residential settings, but without crisis stabilization or acute detoxification services—and generally operate a minimum of 6 hours per day, 5 days per week. Treatments promote functioning in home and work and typically include peer socialization, group support, psychoeducation, life skills training, medication management, individual and family therapy, and complementary and alternative therapies. Although the Army, the Navy, and the Marine Corps have partial hospitalization programs for PTSD, the Air Force does not have any specialized residential, partial hospitalization, or day treatment programs for PTSD and it refers its personnel to other programs if necessary (U.S. Air Force, 2012b).

One example of a civilian partial hospitalization program is Freedom Care, at the University Behavioral Health hospital in El Paso, Texas. Freedom Care treats active-duty service members from Fort Bliss and elsewhere who have combat PTSD, addiction, or a dual diagnosis of PTSD with addiction, military sexual trauma, or other psychiatric diagnoses. The program runs 6 hours per day, 5 days per week; the average stay is 2 weeks. The program offers evidence-based treatments, process and educational group therapy, and other interventions such as art therapy, pet therapy, aquatics, and rock climbing, as well as family therapy and individual therapy for spouses and children, which are offered after hours. On the average, 20 service members participate in the program at any time. Patient outcomes are assessed by using the clinician-administered PTSD scale and the PCL-M, but no program results have been published.

Residential PTSD treatment programs offer 24-hour intensive care with medication management, group psychotherapy, individual and family therapy, and complementary and alternative therapies (O’Toole, 2012). One example is the Overcoming Adversity and Stress Injury Support (OASIS) program at Naval Base Point Loma in San Diego. At any time, there are

two groups of 10 participants in the 10-week program. The program aims to return more than 25% of participants to duty or to an equivalent of satisfactory civilian functioning. The 23 program staff members, including a chaplain, offer a broad array of evidence-based and complementary and alternative therapies in both individual and group formats. Chaplains are an integral part of the OASIS program, where they help with counseling for the moral injury, guilt, and shame that often accompany PTSD (Naval Medical Center San Diego, 2013). OASIS also offers posttraumatic growth classes, couples counseling, and canine therapy, in which service members help to train service dogs for others. Participants who have PTSD and an alcohol problem have daily Alcoholics Anonymous sessions and receive treatment for compulsive behavior. Program leaders report that there are statistically significant differences between pretreatment and posttreatment PCL scores (mean scores, 69 and 58, respectively), and on the before and after assessments, 99% and 82% of patients, respectively, met the diagnostic threshold for PTSD (Naval Medical Center San Diego, 2013).

Most inpatient mental health treatment in DoD focuses on stabilizing a service member in the acute or crisis phase (for example, when people are expressing suicidal or homicidal ideation or attempts). The MTF psychiatric wards visited by the committee generally had fewer than 15 beds. The average number of inpatient bed days per soldier admitted for PTSD was 11.3 (U.S. Army, 2012a) and 10.5 days for Air Force personnel (U.S. Air Force, 2012b).

Finally, each service branch also has a Wounded Warrior program to help service members who need long-term medical support to transition back to active duty (about 2%) or separate from the military. Many service members in these programs have received a diagnosis of PTSD and many have comorbidities, such as TBI, although precise numbers are not available. Case managers coordinate service members’ medical appointments and treatments. Some of those programs, such as the Marine Corps’ Wounded Warrior Battalion, have long-term follow-up designed to monitor the needs and outcomes of program alumni in the years after discharge, but how often such follow-up occurs and whether it is successful in connecting those in need with effective services are unknown.

Rehabilitation Programs and Services

As noted in Chapter 2, PTSD is often accompanied by other psychiatric, medical, or psychosocial conditions, such as alcohol dependence, anxiety, obstructive sleep apnea, lumbago, depression, and rehabilitation procedures that require treatment (Kennell and Associates, 2013). Although treatment of comorbidities is vital for the effective management of PTSD, there is a lack of evidence on how best to treat for PTSD and comorbid conditions.

The National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) on the campus of the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center was established in 2010 to provide state-of-the-art care for service members who have severe mental health problems and TBI. NICoE offers both evidence-based psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy and such complementary and alternative therapies as animal-assisted therapy, biofeedback, journaling, recreation therapy, and mind–body skill building. The program is 4 weeks long and service members are given six clinical evaluations before and after treatment. Of the 293 patients who completed the PCL-M during 2011–2013, 46% had clinically significant improvement (a change of 10 points or more), 32% had improvement below clinically significant levels, 4% had no change, 14% reported worsening of symptoms, and 3% reported clinically significant worsening of symptoms (NICoE, 2013). Those values must be viewed with caution, however, as there is no comparison group. Satellite NICoEs are being built at military installations around the country such as Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

The Navy has some outpatient and inpatient treatment programs that treat for co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders, such as the substance abuse rehabilitation program at the San Diego Naval Base and the OASIS program. Some MTFs, such as that at Fort Campbell, have nearby or colocated clinical services to address PTSD and TBI. However, many military substance use disorder programs do not treat for PTSD. Other medical departments, clinics, and programs that focus on treating such medical conditions as chronic pain, amputations, spinal cord injuries, and severe burns have embedded psychologists, social workers, or other mental health personnel to provide collaborative care for PTSD and comorbid mental health conditions.

One example of a collaborative care program is the Comprehensive Combat and Complex Casualty Care (C5) program at Naval Medical Center San Diego for severely injured service members. An interdisciplinary team provides inpatient clinical management; orthopedics; amputee care and prosthetics; physical, occupational, and recreational therapy; and mental health assessment and treatment, including specialized treatment programs for both PTSD and mild TBI. Each 8-week intensive PTSD treatment cycle has a maximum of eight patients who receive cognitive processing therapy (CPT), group sessions, trauma bereavement, and complementary and alternative therapies (such as art therapy). C5 also involves families in patients’ recovery and offers pastoral care and counseling as well as career transition services. A VA federal recovery coordinator can help patients with the transition to VA care if they are leaving the military. About 2,000 patients have been through C5 since it began in 2006 (Weinick et al., 2011). Patient outcomes are measured with the PCL-M, the Brief Symptom Inven-

tory, and a patient satisfaction survey, but resources for tracking outcomes are not available.

Psychosocial problems (considered to be part of rehabilitation)—such as uncontrolled anger, intimate partner violence, and child maltreatment—may also occur with PTSD. Each service branch has programs and providers to address those issues, but concurrent treatment of PTSD is not required. The programs are staffed by civilians and are generally under the authority of the installation commander, not the MTF. For example, the Marine Corps Community Services program offers nonmedical counseling to marines and their families for marital conflicts, child welfare concerns, and anger management. Family advocacy programs focus on relationship issues and offer marriage and family therapy but not PTSD treatment, although they may make referrals. This lack of integration between PTSD treatment programs and those for co-occurring psychosocial issues may make it difficult to comprehensively treat them both.

Evaluations of DoD Programs and Services

The increase in PTSD-related programs available to service members and their families has prompted DoD to initiate several evaluations of them, both internal and external. The DoD Task Force on Mental Health (2007) found that although a great variety of mental health services and programs were offered at military installations—including family, medical, and religious programs—there were “various degrees of segregation of these programs and no consistent plan for collaboration in promoting the psychological health of service members and their families.” The report also noted that “the services are stovepiped at the installation and service levels.” This section discusses some of the most recent and comprehensive evaluations of DoD programs and services for PTSD.

Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoEs)

DCoE was established to lead and streamline DoD efforts to coordinate the prevention of and care for mental health conditions and TBI for service members and their families (GAO, 2012). Previously, no organization or entity had coordinated or monitored all such existing DoD activities (Weinick et al., 2011). DCoE can only make recommendations to the ASD(HA); it does not have authority to establish or enforce policies (GAO, 2011a).

In a review of 211 DoD mental health and TBI programs, Weinick et al. (2011) found that only about 23% of them had conducted an outcome evaluation in the previous year, and only 45% had collected any outcome data. In response to that review, in 2012, DCoE launched its own review

of 166 DoD mental health, suicide, and substance abuse programs to identify those programs believed to have the highest-quality care and the best outcomes as well as programs in need of assistance and those that could be eliminated. The evaluation report was completed in 2013 but is not available for review.

To assist DoD mental health leaders in determining the effectiveness of their programs, the RAND Corporation developed a Program Evaluation Guide for DCoE, a step-by-step how-to manual for conducting standardized program evaluations (DCoE, 2012). Although the guide is comprehensive, its use by DoD program managers is neither required nor monitored by DCoE (Carleton Drew, DCoE, personal communication, January 9, 2014), and there is no information as to whether it is being used by any DoD PTSD or other mental health program managers to assess their programs.

The Deployment Health Clinical Center (DHCC), a component of DCoE, is involved in clinical care, health services delivery research, and clinical education and outreach. It has a specialty care program specific to PTSD, deployment-related stress, and difficulties in adjusting to postdeployment life. The Tri-service Integrator of Outpatient Programming Systems (TrIOPS) activity within the Deployment Health Clinical Center is evaluating and attempting to synchronize the treatments offered in the 21 PTSD intensive outpatient programs among the service branches (O’Toole, 2012). The TrIOPS survey indicated that outcomes are typically assessed by using the PCL (80%), but no outcome data were reported and a formal evaluation of the programs is not available.

Institute of Medicine

In March 2014 the IOM released its report Preventing Psychological Disorders in Service Members and Their Families that evaluated risk and protective factors for mental health in these populations and suggested that prevention strategies are needed at multiple levels—individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and societal. The report reviewed and critiqued DoD reintegration programs and prevention strategies for PTSD, depression, recovery support, and prevention of substance abuse, suicide, and interpersonal violence. Although an array of programs exists, the report found that DOD’s current infrastructure does not support optimal programming. It recommended that DoD implement evidence-based resilience, prevention, and reintegration programs and eliminate non-evidence-based programs; use a systematic approach to existing evidence-based measures; use validated psychological screening instruments and conduct systematic targeted prevention annually and across the military life cycle (from accession to separation) for service members and their families; implement comprehensive universal, selective, and indicated evidence-based preven-

tion programs targeting mental health in military families; and use existing evidence-based community-level prevention interventions.

RAND Corporation

The RAND Corporation has conducted several in-depth program and service evaluations for DoD, including assessment of selected prevention and resilience programs to determine those that incorporate evidence-informed practices (Meredith et al., 2011). It has also estimated the prevalence of mental health conditions in service members and identified gaps in DoD’s mental health care services, especially for PTSD, depression, and TBI (Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008).

During 2009–2011, RAND developed a comprehensive catalog of psychological health programs sponsored or funded by DoD. It identified 211 programs of which 103 were PTSD-related (Weinick et al., 2011); those programs are listed in Appendix C of the committee’s phase 1 report. However, the survey only cataloged the programs, using a very specific definition of a program, and did not assess their effectiveness or efficacy. The report also did not assess traditionally delivered clinical services for PTSD, including treatment modalities, offered in MTFs. The authors of the report stated that, in general, the programs did not collect data on their effectiveness and that, even when they did, such data were not publicly available for assessment. Most of the programs were relatively new, few service members had completed them, and long-term follow-up data were not collected. The report also concluded that knowledge and materials are seldom shared between programs, no single authority within DoD or any of its service branches maintains a complete listing of current or developing programs, and their uncoordinated proliferation may lead to substantial inefficiencies (Weinick et al., 2011).

RAND conducted an in-depth program evaluation of the Real Warriors Campaign (Acosta et al., 2012), a DoD-wide multimedia program to build and promote resilience, facilitate recovery, and support the reintegration of returning service members, veterans, and their families. The evaluation found several problems with the website and campaign materials; for example, communication metrics are not being used to guide strategic decisions about the campaign, there are no progress or outcome evaluations, and there is no feedback on the website or review of the site’s usability. A similar evaluation of the DoD inTransition program is expected to be completed in 2014.

Samueli Institute

The Samueli Institute, a nonprofit research organization supported by DoD, has evaluated several base-specific program initiatives at the Marine Corps Camp Lejeune. Similar to the aforementioned RAND Corporation report findings, the institute found that there is no central resource for tracking or accessing the vast number and different types of mental health programs available on base or in the community; this makes it difficult for anyone to find the best services to meet the need of a marine and his or her family.

RAND and the Samueli Institute conducted a joint program evaluation of the Warrior Optimization Systems at Fort Carson, Colorado. This 4-hour training program helps soldiers to learn stress management and self-regulating skills for coping with combat and operational stresses, enhancing resilience, improving performance, and facilitating reintegration. Soldiers who attended the program reported greater resilience and had fewer PTSD symptoms and better postdeployment reintegration than those who did not (Samueli Institute, 2013a).

The institute has evaluated several studies of specific complementary and alternative therapies to assess their potential for treating PTSD, such as healing touch with guided imagery (Jain et al., 2012) and acupuncture (Lee et al., 2012). The institute is currently evaluating relaxation response training at Fort Bliss to determine whether this program can reduce trauma symptoms in soldiers who have screened positive for symptoms of PTSD (Samueli Institute, 2013b).

DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS

VA offers a broad array of health care services, including primary and specialized medical and mental health services as well as adjunct services that help veterans with employment, housing, and social issues. This section provides a brief overview of the organization of VA mental health offices, followed by descriptions of VA prevention programs and services, screening and diagnostic services, treatment programs, and examples of rehabilition programs available to veterans who have PTSD. The section concludes with an overview of PTSD program evaluations that have been conducted by VA or other organizations.

Organization

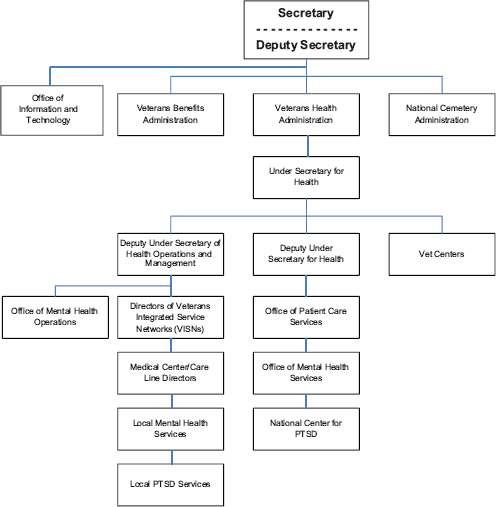

In July 2011, VA announced a reorganization of mental health programs and services in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) central office to enhance oversight and reduce variation in the delivery of mental

health services throughout the VA health care system (Schoenhard, 2011). The Office of Mental Health Operations (OMHO), which ensures the implementation of mental health policies, and the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) directors report directly to the deputy under secretary for health for operations and management (see Figure 3-3). The Office of Mental Health Services, which works closely with OMHO, will continue to develop mental health policy and will also take the lead in working with DoD to develop and disseminate evidence-based practice guidelines for PTSD management. The VA Office of Information and Technology,

FIGURE 3-3 VA organization chart showing PTSD management responsibilities in various mental health departments and services.

which reports to the Office of the Secretary of the VA, provides strategy and technical direction, guidance, and policy for all information technology resources, including the maintenance of the electronic health record system.

VA has issued a number of policies, directives, guidelines, and handbooks on mental health services and programs. Primary among them is the VHA Handbook 1160.01, Uniform Mental Health Service in VA Medical Centers and Clinics (VA, 2008) which establishes the minimum clinical requirements for VA mental health services in medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) and specifies those program components that must be available to ensure that all veterans receive equitable care throughout the VA health care system. PTSD services are also detailed in the VHA Handbook 1160.03, Programs for Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (VA, 2010), which establishes procedures for a continuum of PTSD programs for veterans from screening to rehabilitation.

National Center for PTSD

Many of VA’s PTSD programs and research initiatives originate in its National Center for PTSD, which has several sites around the country. The center focuses on PTSD research; the education of veterans, their families, and professionals; and the promotion of best practices. Best-practices efforts for PTSD include assisting in the 2010 revision of the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress), product development (such as mobile applications for PTSD; websites; the VA CPT manual; and assessment tools, including the Primary Care-PTSD screen and the PCL), professional training, and program support and evaluation. The center is also trains VA mental health professionals in CPT and prolonged exposure (PE) therapy via an onsite clinical training program; mentoring PTSD program managers to promote best practices, continuing education and problem solving; and providing expert PTSD consultation to any VA clinician who treats for PTSD. The public Web page of the National Center for PTSD helps veterans find a treatment facility near them, has testimonials from veterans about the benefits of treatment for PTSD, and links to other resources such as PTSD Coach Online. The provider Web page allows access to the PILOTS database that contains references to the world literature on PTSD and has information on PTSD assessment tools and screens, clinical training tools, and a military culture course.

Prevention Programs and Services

In the forefront of VA prevention activities are the 300 readjustment centers (Vet Centers) that assist veterans in returning to civilian life. Services

include individual, group, and family counseling; employment counseling; counseling related to military sexual trauma (MST)2; outreach; substance use disorder assessment and referral; bereavement counseling; referral for other mental health and medical problems; and guidance on VA benefits. Combat veterans of any era—including current OEF and OIF active-duty, National Guard, and reserve service members—may use Vet Center services. In 2013, almost 200,000 veterans and their families visited a Vet Center and the Vet Center Combat Call Center received almost 44,000 calls. The 70 mobile Vet Centers are used for outreach and to increase access to the estimated 41% of veterans in the VA system who live in rural areas (GAO, 2011c).

Screening and Diagnosis Services

It is VA policy to screen every patient who is seen in a primary care clinic for PTSD, MST, depression, and problem drinking during the patient’s first appointment. Screenings for depression and problem drinking are repeated annually for as long as a veteran uses services, but PTSD screening is repeated annually for the first 5 years and once every 5 years thereafter (Schoenhard, 2011; VA, 2008). Affirmative answers to 3 of the 4 questions on the Primary Care PTSD screen result in an additional screening for suicide. MST is screened for only once, generally at the first appointment, unless new information indicates the need for additional screenings. Vet Centers also screen all veterans for PTSD and MST and veterans may also self-screen through VA’s My Health eVet website (VA, 2012c).

VA policy stipulates that all veterans who receive a mental health referral on the basis of a positive screen must be contacted within 24 hours for an immediate medical needs evaluation, and receive follow-up care within 14 days of referral in nonemergency situations (GAO, 2011c; VA, 2008). The numbers of veterans screened, referred to diagnosis, and referred for treatment could not be determined because such referrals are not coded in a consistent way in the administrative medical record.

Treatment Programs and Services

VA medical centers offer a full array of treatment services for PTSD, including pharmacotherapy, face-to-face mental health assessment and diagnosis, group and individual therapy, and psychotherapy (particularly

________________

2Military sexual trauma is a term used in VA for “sexual harassment that is threatening in character or physical assault of a sexual nature that occurred while the victim was in the military, regardless of geographic location of the trauma, gender of the victim, or the relationship to the perpetrator” (VA, 2012b).

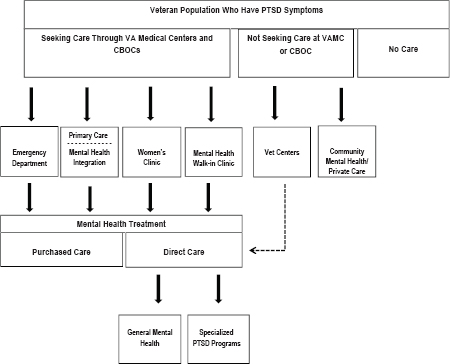

the evidence-based CPT and prolonged exposure [PE] therapy). Figure 3-4 shows the various treatment pathways available to a veteran who is diagnosed with PTSD. The most common treatment setting is in general mental health outpatient clinics, although some veterans may receive care in more than one venue; for example, a veteran who receives psychotherapy from an outpatient PTSD clinical team may continue to receive follow-up care in a general mental health clinic or primary care setting. VA tracks the location (but not the type) of treatment given by assigning a code to every outpatient clinic and every inpatient or residential bed setting.

Each VA medical center has at least one “PTSD specialist” (VA, 2008) who is expected to have expertise in treatment for PTSD. These specialists

FIGURE 3-4 PTSD treatment pathways available in VA. Most PTSD treatment occurs in general mental health clinics or primary care clinics. Veterans may also receive counseling for PTSD symptoms in Vet Centers or from private community mental health care providers or choose to receive no care at all. The dotted line between Vet Centers and Direct Care is to show that some Vet Centers provide psychotherapy for PTSD or may refer veterans to another VA setting for direct care. Primary care and mental health practitioners are moving to a model in which mental health practitioners are embedded in primary care teams. Specialized PTSD programs are available for veterans who require more intensive services.

enter treatment information into the electronic health record by using a special PTSD encounter code; treatment outcomes are not reported. Each VA medical center has also appointed a coordinator to serve as a clinical champion for evidence-based psychotherapies and to promote clinical infrastructures that support their delivery.

Primary Care Centers

Many veterans receive PTSD treatment in VA primary care clinics. In 2011, 10.4% of veterans seen in primary care had a diagnosis of PTSD, compared with 3.5% of all U.S. patients (Klein, 2011). VA has been integrating collaborative mental health and other medical resources into primary care settings to establish patient-aligned care teams (PACTs; originally called Primary Care-Mental Health Integration) (Klein, 2011), a form of the PCMH. As of 2011, integrated care had been implemented in 124 of 140 VA medical facilities (Kearney et al., 2011). Mental health care providers in primary care teams may prescribe medications to manage low to moderate symptoms of PTSD, provide psychological treatments, work as case managers, and provide referrals to specialty PTSD care when warranted. During site visits to VA facilities, both primary care and mental health care providers indicated that the PACT approach was effective in treating veterans who have PTSD and reducing the number of referrals for specialty care.

Specialized Outpatient PTSD Programs (SOPPs)

VA has 166 specialized outpatient and inpatient PTSD treatment programs (VA, 2012a). There are 127 specialized outpatient PTSD programs (SOPPs): 120 PTSD clinical teams, four substance use PTSD teams, and three women’s stress disorder treatment teams. SOPPs may have specific inclusion or exclusion criteria, such as substance use disorder status or legal status (for example, not awaiting trial or sentencing), but there is no uniform, national policy on admission criteria. Services provided by the interdisciplinary PTSD clinical teams include assessment and diagnosis; individual, group, and family therapy; psychoeducation; pharmacotherapy and medication management; supportive therapy; cognitive behavioral therapy, PE, and CPT; and referrals to other services or clinics. There is no standardized approach to treatment although all veterans are to be offered PE or CPT. Substance-use PTSD teams provide assessment, symptom management, and group and individual psychotherapy. Women’s stress disorder treatment teams are similar in structure to the PTSD clinical teams and provide face-to-face and group treatment to female veterans. Treatment approaches are similar to those of other SOPPs.

In 2012, of the 502,546 veterans who had PTSD and used VA services,

146,615 (29.2%) were seen in SOPPs, compared with 81,423 veterans in 2004 (37.5%); 27,904 (26%) of the patients seen in the SOPPs in 2012 were new (VA, 2011, 2012a). Thus, despite a large increase in the number of veterans seen in SOPPs from 2004 to 2012, a smaller percentage of veterans were receiving treatment in them. The frequency of visits (VA uses the term intensity of treatment) also appears to have decreased in the specialized PTSD programs, including the SOPPs, over the last decade. The average number of PTSD-related stops (visits) per veteran who received care in any VA setting declined from 12.53 in 2002 to 10.91 in 2011 (VA, 2011). In 2004, the average number of SOPP visits per veteran was 8.5; it decreased to 7.4 in 2012 (VA, 2011, 2012a). The committee suggests that reasons for the decline may include staffing shortages, high treatment dropout rates, and treatment completion in fewer sessions, but no data are available to confirm this.

Of the 16,736 veterans who entered a SOPP (and for whom data are available) during 2012, 43% had served in OEF or OIF (VA, 2012a) and 34% in Vietnam; 89% were male, 64% were Caucasian, 81% had been exposed to enemy or friendly fire, and 37% were applying for PTSD-related service connection. Comorbidities were high in veterans in the SOPPs: 29% had a concurrent diagnosis of substance use disorder, 54% had a non-psychotic axis I diagnosis,3 4% had a psychotic axis I diagnosis, and 60% had a chronic medical problem (VA, 2012a). Only 1% were currently on active duty, but 5% were still active in the reserves or National Guard (VA, 2012a). MST during time in service was reported by 20%, and 14% reported sexual trauma either before or after their time in service (sex not specified).

Specialized Intensive PTSD Programs (SIPPs)

In 2012, VA had 39 SIPPs that provided care to a relatively small number of patients (3,792, 0.7% of all VA PTSD patients). There are six types of SIPPs: evaluation and brief-treatment PTSD units, PTSD residential rehabilitation programs, PTSD domiciliary programs, PTSD day hospitals, specialized PTSD inpatient programs, and female trauma recovery programs (VA, 2012a). The programs were locally developed and so are different from each other in structure (for example, residential vs day hospital), length of stay (average, 42.1 days; range, 21.7–76.8 days; VA, 2012a), and

________________

3 The American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders uses a five-axis system to diagnose mental health disorders (APA, 2000): axis I includes clinical disorders, axis II includes personality disorders and mental retardation, axis III includes general medical conditions, axis IV includes psychosocial and environmental problems, and axis V includes global assessment of functioning.

treatment approach. Most programs are comprehensive, offering a variety of interventions and treatment options, including evidence-based therapies and complementary and alternative therapies.

SIPPs provide trauma-focused treatment for veterans who require more intense and monitored care. Evaluation and brief treatment PTSD units provide 14–28 days of care for acute cases in inpatient psychiatric units with mandatory follow-up care after a stay. PTSD day hospitals provide intensive outpatient care for 3–6 weeks in individual or group settings (VA, 2010). PTSD residential rehabilitation programs and PTSD domiciliary programs also provide longer-term care, generally for 28–90 days, to prepare veterans to re-enter the community (VA, 2010).

The women’s trauma recovery programs are 60-day live-in rehabilitation programs that include PTSD treatment and coping skills for reentering the community. There are only two such programs in VA, and they served a total of 73 women in 2012. About 6.4% of all VA users, 7% of participants in all SIPPs, and 10% of all patients in SOPPs are female (VA, 2012a).

Most patients in SIPPs have served in OEF and OIF (36%) or Vietnam (32%). The majority of program participants (65%) had a current chronic medical problem, and 18% were participating in a pain-management component of PTSD treatment. In addition, 81% reported that they had been exposed to enemy or friendly fire; of the 1,381 (36%) who had noncombat-related PTSD, 20% reported MST and 16% non-military sexual trauma. SIPP participants have comorbidities that include substance use disorders (47%), axis I nonpsychotic disorders (45%), and axis I psychotic disorders (9%). At admission, 84% were not working (VA, 2012a).

The Readjustment Counseling Service estimates that 36% of all veterans who receive Vet Center services for any reason are not seen in any other VA facility (Fisher, 2014). In 2012 and the first quarter of 2013, a total of 261,998 OEF and OIF veterans who had PTSD were seen in a VA medical center, and 70,044 veterans received service for PTSD in Vet Centers. Of these, 216,090 were seen only in a VA medical center, 24,136 only in a Vet Center, and 45,908 in both kinds of facilities (VA, 2013). Fourteen Vet Centers are colocated with CBOCs.

Rehabilitation Programs and Services

The scope of rehabilitation needs for veterans is broad, particularly for those with some of the most impairing outcomes. For example, veterans who have PTSD are over-represented in incarcerated, homeless, substance-dependent, and chronically unemployed groups. Some VA programs have active outreach to these populations such as the homeless programs and the OEF/OIF/Operation New Dawn teams and OEF/OIF Coordinators who identify and work with these veterans in their catchment areas. VA

offers a full array of rehabilitation services to veterans who have PTSD, including vocational rehabilitation, such as compensated work therapy, the Department of Housing and Urban Development–VA Supportive Housing program for homeless veterans, and a full spectrum of state-of-the-art physical rehabilitation services.

The Veterans Benefit Administration (VBA) evaluates and adjudicates all claims for service-connected PTSD. It also provides rehabilitation services for those who are substantially impaired by service-connected PTSD, including evaluation services, and educational and vocational-training services. VBA staff provides some of the initial evaluation services and act as case managers in the rehabilitation process. Most services are provided through payments by VBA to educational, vocational, and rehabilitation organizations or individual service providers. VBA also provides additional services for patients who have PTSD, such as loans, non-service-connected pensions, and education benefits. Those services are available for all veterans who have PTSD, regardless of whether their PTSD has been adjudicated as being service-connected.

Evaluations of VA Programs and Services

VA conducted a review of the mental health programs and services in its 140 medical facilities during 2012 and provided the evaluation report to the committee in November 2013. VA also sponsored the RAND and Altarum Institute report Veterans Health Administration Mental Health Program Evaluation: Capstone Report (Watkins et al., 2011), which evaluated the quality of care delivered to veterans with PTSD and four other mental health or substance use diagnoses. These reports are discussed in greater detail below.

Veterans Health Administration

A primary VA mental health program evaluation effort is the national baseline assessment of the implementation of the VHA handbook Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics conducted by OMHO (2013). For this effort, the 140 VA health care facilities completed an electronic questionnaire for 19 health care and service domains, including PTSD. Specific qualitative evaluation metrics included whether specialty PTSD treatment was implemented as required by the handbook, the use of prescription medications, and whether the services were being provided in a timely manner. OMHO used the survey responses and site visit interviews to assess the strengths and needs for improvement of all facilities.

The results of the site visits were evaluated with qualitative research methods; specifically, the final summaries of the reports of the site visits

were analyzed by using software that identified key words and phrases. Specific findings from the OMHO report are discussed in other chapters of this report. The percentages reported in the qualitative analysis, although useful for identifying system-wide strengths and weaknesses, are not comparable with quantitative data, and thus the results of the OMHO survey must be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, it cannot be assumed that a failure to mention a specific mental health concern, such as wait times, in the survey indicates that it is not an issue in a particular site (OMHO, 2013).

RAND Corporation and Altarum Institute

RAND Corporation and the Altarum Institute conducted an in-depth 4-year evaluation (2006–2010) of VA mental health care and services for 836,699 veterans who had a diagnosis of PTSD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, or substance use disorder. This effort included the development of 88 performance indicators, 31 of which could be evaluated with administrative data alone, and the other 57 required both administrative and medical record data. There were four categories of indicators: quality and extent of diagnosis and assessment practices, quality and extent of treatment processes, chronic disease management, and rehabilitation. For example, one of the indicators for PTSD was the proportion of veterans with the diagnosis who had a new treatment episode documented for PTSD symptoms with a standard instrument within 30 days of the episode. A medical record review showed that only 5.6% of the PTSD cohort (357,289 veterans) met this indicator (Watkins et al., 2011). Most of the performance indicators did not show significant improvement over the study duration, but a large number of veterans initiated VA services over this period.

Other key finding in the report included lack of standardization and classification of clinical assessment and treatment practices for use in administrative data sets, inadequate development and dissemination of mental health performance measures, infrequent use of outcome measures in clinical practice, and lack of process coordination. Inherent weaknesses in the data systems—such as administrative data that are separate and not linked to pharmacy, laboratory, or cost data sets—seriously impeded the use of the information in these databases to improve quality of care. Although veterans in this cohort comprised only 16.5% of the VA patient population, they accounted for about 41% of acute inpatient discharges, 40% of outpatient encounters, and 34% of total costs. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and specialized services for PTSD were reported to be available at 96–99% of VA medical centers and 64–88% of CBOCs, but only 20% of veterans who had PTSD had documented use of at least one psychotherapy with cognitive behavioral therapy elements. Veterans who had PTSD and received cognitive behavioral therapy had a mean of 13.5 visits (time frame not given).

Government Accountability Office

GAO has conducted several studies of VA PTSD management activities since the beginning of OEF and OIF. In 2005, GAO reported that VA needed to improve PTSD services (GAO, 2005), and in 2011 it found that there were substantial barriers for veterans in accessing VA mental health care (GAO, 2011c). Recently it has assessed VA PTSD research funding and found that “from fiscal year 2005 through fiscal year 2009, intramural PTSD-research funding ranged from 2.5 percent to 4.8 percent of VA’s medical and prosthetic research appropriation.” It noted that VA incorporates research findings into its clinical practice guidelines (GAO, 2011b).

SUMMARY

DoD and VA offer a broad array of programs and services to prevent, screen, diagnose, and treat for PTSD in service members and veterans in military installations and VA medical facilities. DoD puts more emphasis on preventing the development of PTSD than does VA, and each service branch has developed some form of a combat and operational stress control and resilience program with mandatory participation. VA prevention efforts focus primarily on the use of Vet Centers to provide veterans with counseling and referrals.

Most service members and veterans who have mild symptoms of PTSD receive care in primary care or general mental health clinics. Both DoD and VA are integrating mental health providers in primary care clinics to reduce barriers to care. These collaborative care teams can result in fewer referrals to specialty care, better long-term outcomes (after specialty care is complete), and more coordinated care for comorbidities. All the service branches and many VA medical centers have a version of a patient-centered medical home. Those who have more severe PTSD symptoms may be treated in a general mental health clinic. Service members and veterans with the most severe symptoms and those who have not responded to prior treatments may be admitted to specialized outpatient or inpatient programs. In DoD, there are 21 such programs, such as the Warrior Resilience Center at Fort Bliss, and they offer a variety of evidence-based and complementary and alternative therapies. However, these individually conceived and developed programs treat only small numbers of service members each year and their effectiveness is not known.

In VA, the 127 SOPPs and 39 SIPPs treat a relatively small number of veterans who have PTSD, 29% and less than 1%, respectively. They, too, offer a variety of evidence-based therapies, primarily CPT and PE, but many of them also offer complementary and alternative therapies. There are three SOPPs and two SIPPs specifically for female veterans. Despite the

increase in the number of veterans seen in SOPPs from 2004 to 2012, a smaller percentage of veterans who have PTSD are receiving treatment in them, and the number of outpatient visits per veteran also declined during this time. The reasons for this reduction in service are unclear and may be due to a number of factors, but they warrant further consideration. VA also provides rehabilitation and support services to veterans who have PTSD and comorbidities, such as homelessness and unemployment, and other benefits such as disability evaluations and compensation.

Internal and external evaluations of DoD and VA PTSD programs and services have been undertaken by numerous organizations. Virtually all of the evaluations of both departments have found the lack of data on which to make quantitative assessments of the programs’ effectiveness to be a major shortcoming. The most recent evaluation of DoD mental health programs prepared by DCoE is unavailable. The VA collects more programmatic information than does DoD, but outcome data are still scarce. The use of performance metrics to address this issue is discussed in the next chapter.

REFERENCES

Acosta, J. D., L. T. Martin, M. P. Fisher, R. Harris, and R. M. Weinick. 2012. Assessment of the content, design, and dissemination of the Real Warriors Campaign. TR-1176-OSD. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fourth edition-text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Blakeley, K., and D. J. Jansen. 2013. Post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in the military: Oversight issues for congress. Congressional Research Service. R43175. Washington, DC.

DCoE (Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury). 2012. PTSD treatment options webpage. http://www.dcoe.mil/ForHealthPros/PTSDTreatmentOptions.aspx (accessed January 14, 2013).

Dinneen, M. 2011. Military health system overview. Presentation to the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. Washington, DC: DoD Office of Strategic Management. February 28, 2011.

DoD (Department of Defense). 2011a. DoDI 6490.03—Deployment health (certified current as of September 30, 2011). Washington, DC.

DoD. 2011b. DoDI 6490.05—Maintenance of psychological health in military operation. Washington, DC.

DoD. 2013a. DoDI 6490.15—Integration of behavioral health personnel (BHP) services into patient-centered medical home (PCMH) primary care and other primary care service settings. Washington, DC.

DoD. 2013b. Report to Congress on the Institute of Medicine report “Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations: Initial assessment.” Washington, DC: DoD, Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness.

DoD Task Force on Mental Health. 2007. An achievable vision: Report of the Department of Defense Task Force on Mental Health. Falls Church, VA: Defense Health Board.

DoD/VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2011. DoD/VA Integrated Mental Health Strategy (IMHS): Strategic Action Summaries. January 3, 2011.

Engel, C. C., T. Oxman, C. Yamamoto, D. Gould, S. Barry, P. Stewart, K. Kroenke, J. W. Williams, and A. J. Dietrich. 2008. RESPECT-Mil-feasibility of a systems-level collaborative care approach to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in military primary care. Military Medicine 173(10):935-940.

Fisher, M. 2014. Readjustment counseling services response to data request (Vet Center update) from the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. VA. Washington, DC. January 9, 2014.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2005. VA health care: VA should expedite the implementation of recommendations needed to improve post-traumatic stress disorder services. GAO-05-287. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2008. VA and DoD health care: Administration of DoD’s post-deployment health reassessment to National Guard and reserve servicemembers and VA’s interaction with DoD. GAO-08-181R. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2011a. Defense health: Management weaknesses at Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury require attention. GAO-11-219. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2011b. VA health care: VA spends millions on post-traumatic stress disorder research and incorporates research outcomes into guidelines and policy for post-traumatic stress disorder services. GAO-11-32. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2011c. VA mental health: Number of veterans receiving care, barriers faced, and efforts to increase access. GAO-12-12. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

GAO. 2012. Defense health: Coordinating authority needed for psychological health and traumatic brain injury activities. GAO-12-154. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Jain, S., G. F. McMahon, P. Hasen, M. P. Kozub, V. Porter, R. King, and E. M. Guarneri. 2012. Healing touch with guided imagery for PTSD in returning active duty military: A randomized controlled trial. Military Medicine 177(9):1015-1021.

Kearney, L. K., E. P. Post, A. Zeiss, M. G. Goldstein, and M. Dundon. 2011. The role of mental and behavioral health in the application of the patient-centered medical home in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Translational Behavioral Medicine 1(4):624-628.

Kennell and Associates, Inc. 2013. DoD response to data request from the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. Falls Church, VA. September 12, 2013.

Klein, S. 2011. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing patient-centered medical homes in the nation’s largest integrated delivery system. Publication # 1537. New York: The Commonwealth Fund.

Lee, C., C. Crawford, D. Wallerstedt, A. York, A. Duncan, J. Smith, M. Sprengel, R. Welton, and W. Jonas. 2012. The effectiveness of acupuncture research across components of the trauma spectrum response (TSR): A systematic review of reviews. Systematic Reviews 1(1):46.

Marine Corps Combat Development Command and Navy Warfare Development Command. 2010. Combat and operational stress control. Quantico, VA.

Meredith, L. S., C. D. Sherbourne, S. J. Sherbourne, S. J. Gaillot, L. Hansell, A. M. Parker, G. Wrenn, and H. V. Ritschard. 2011. Promoting psychological resilience in the U.S. Military. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Nash, W. P. 2006. Operational Stress Control and Readiness (OSCAR): The United States Marine Corps initiative to deliver mental health services to operating forces. In Human Dimensions in Military Operations—Military Leaders’ Strategies for Addressing Stress and Psychological Support. Meeting Proceedings RTO-MP-HFM-134, Paper 25. Neuilly-sur-Seine, France: North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Research and Technology Organisation. Pp. 25-1-25-10.

Nash, W. P. 2011. U.S. Marine Corps and Navy combat and operational stress continuum model: A tool for leaders. In Combat and Operational Behavioral Health, Textbooks of Military Medicine Series, edited by E. C. Ritchie. Washington, DC: Borden Institute.

Nash, W. P., and P. J. Watson. 2012. Review of VA/DoD clinical practice guideline on management of acute stress and interventions to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 49(5):637-648.

Naval Medical Center San Diego. 2013. Overcoming Adversity and Stress Injury Support (OASIS) program pre-/post-cumulative report: April 21, 2011 to March 31, 2013. Edited by Naval Center for Combat and Operational Stress Control (COSC).

NICoE (National Intrepid Center of Excellence). 2013. The National Intrepid Center of Excellence. Presentation to the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. Bethesda, MD. November 12, 2013.

OMHO (Office of Mental Health Operations). 2013. Draft report: Office of mental health operations FY2012 site visits. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs. May 7, 2013.

O’Toole, J. C. 2012. Tri-service integrator of outpatient programming systems (TrIOPS). Presentation to the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. DCoE. Silver Spring, MD. December 10, 2012.

Samueli Institute. 2013a. Evaluation of WAROPS® (warrior optimization systems) training program—Fort Carson, CO—July 2012. Alexandria, VA.

Samueli Institute. 2013b. Relaxation response (RR) training for PTSD prevention in soldiers. Alexandria, VA.

Schoenhard, W. 2011. Statement to the Senate Committee on Veteran’s Affairs July 14, 2011. http://veterans.senate.gov/hearings.cfm?action=release.display&release_id=796c41ee3006-4647-b461-920653c6425e (accessed April 27, 2012).

Tanielian, T., and L. H. Jaycox (Eds.). 2008. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

TRICARE Management Activity. 2013. Evaluation of the TRICARE program: Access, cost, and quality, FY2013 report to Congress. Alexandria, VA: DoD.

U.S. Air Force. 2006. Air Force Instruction 44-153: Traumatic stress response. Secretary of the Air Force. September 20, 2012.

U.S. Air Force. 2011. Primary behavioral health care services practice manual. Lackland AFB, TX: Air Force Medical Operations Agency (AFMOA).

U.S. Air Force. 2012a. Air Force Instruction 10-403: Deployment planning and execution. Secretary of the Air Force.

U.S. Air Force. 2012b. Air Force response to data request from the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. Washington, DC. May 14, 2012.

U.S. Air Force. 2013. DGS-I take aways (Langley AFB). Washington, DC. November 2013.

U.S. Army. 2012a. Army response to data request from the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. Washington, DC. June 6, 2012.

U.S. Army. 2012b. Comprehensive solder fitness. http://csf.army.mil (accessed January 30, 2012).

U.S. Army. 2013a. Information paper: Army behavioral health service line (BHSL). Washington, DC. October 10, 2013.

U.S. Army. 2013b. Stand-to! Today’s focus: Ready and resilient campaign: Embedded behavioral health (Edition: Tuesday, August 13, 2013). http://www.army.mil/standto/archive_2013-08-13 (accessed October 21, 2013).

U.S. Navy. 2013. Navy and Marines response to data request from the Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of PTSD. Washington, DC. November 18, 2013.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2008. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. VHA Handbook 1160.01. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration.

VA. 2010. Programs for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). VHA Handbook 1160.03. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration.

VA. 2011. The Long Journey Home XX: Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). West Haven, CT: Northeast Program Evaluation Center.

VA. 2012a. The Long Journey Home XXI: Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). West Haven, CT: Northeast Program Evaluation Center.

VA. 2012b. Military sexual trauma. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/military-sexualtrauma-general.asp (accessed January 30, 2012).

VA. 2012c. My HealtheVet–the gateway to veteran health and wellness. https://www.myhealth.va.gov/index.html (accessed January 30, 2012).

VA. 2013. Report on VA facility specific Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans coded with potential PTSD: Cumulative from 1st quarter FY 2002 through 1st quarter FY 2013 (October 1, 2001–December 31, 2012). Washington, DC.

VA/DoD (Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense). 2010. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress. Washington, DC: VA and DoD.