CHAPTER FIVE

Building Knowledge and Solving Problems

We want to understand the wonder of the world around us. We want to use what we learn to improve our circumstances, to support human well-being and dignity. We want to mitigate harmful impacts where possible and adapt as best we can to changing conditions. We want to anticipate what lies over the horizon so that we are better prepared to meet future challenges (Box 5.1). All of these motivations apply to Arctic research, as scientists study the inherent fascination of a rapidly changing region dominated by ice in many forms and as society figures out how best to face the challenges and pursue the opportunities emerging there.

Curiosity-driven research and problem-oriented research are often held up as competing and even mutually exclusive approaches. This dichotomy is a reflection more of agency funding priorities and mechanisms and less a fundamental property of the research enterprise itself. In practice, and as demonstrated by the many examples described in this report, our understanding of the Arctic benefits from both approaches, and the ability to act on Arctic matters requires insights from all points on the research spectrum. Because this dichotomy is misleading, we should not seek to identify an “optimal balance” between research on fundamental questions versus that on specific, urgent problems. It is more productive to think about the ways in which decision makers and communities can draw on the results of all types of research to find appropriate paths for action as well as the innovative research that emerges when researchers direct their inquiry toward what decision makers need to know.

Natural and social scientific study can provide an objective basis for developing a common understanding of the phenomena and processes that define and shape the Arctic. It has the potential to provide lines of evidence for making decisions about how to live and work in the Arctic, recognizing that our knowledge will never be complete but that using the best available information can support decisions that meet our goals now while leaving us better prepared for, and resilient to, future shocks.

For all regions of the planet where accelerated impacts of climate change are occurring, it is well recognized that, if action had been taken earlier to tackle global warming using the science available at that time, the results would likely have been different, with more positive environmental outcomes. This lack of action strongly suggests

BOX 5.1 LAST SEA ICE REFUGE

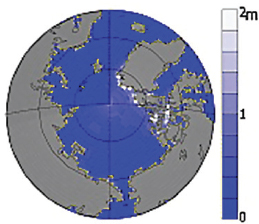

The record-setting losses of sea ice in 2007 and 2012 resulted in widespread attention to the question of when the Arctic will be ice free in summer. But a closer look at the model results leads to an important finding: After most of the ice is lost, many projections show some sea ice cover extending far into the latter half of this century. The modeled ice distributions (Figure) project that this last remaining summer sea ice will be located north of Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago, in a region known as the last sea ice refuge or the last ice area (Pfirman et al., 2009; Wang and Overland, 2009; WWF, 2012). Because winds drive winter ice into this region, it is expected to continue having contiguous ice cover in summer for decades after sea ice is lost throughout the rest of the Arctic. This means that polar bears, ringed seals, and other species dependent on sea ice will likely find supportive habitat in this region throughout much of the 21st century (Durner et al., 2009; Kelly et al., 2010).

FIGURE Model projections of sea ice thickness when the Arctic is nearly ice free in September, within 30 years. Units for sea ice thickness are meters. SOURCE: Wang and Overland, 2009.

that the science-policy-practice link is broken (Weichselgartner and Marandino, 2012). These authors point to a need to improve the ways in which science is used to develop policies and other tools for managing marine environments, but this need also applies to the Arctic. They also suggest that, in general, improving how science is translated to knowledge, synthesizing existing local knowledge, and engaging regional communities to develop decision support systems are some of the important ways in which this broken link can be repaired.

Arctic research is already an important underpinning of U.S. investments in resource exploration, wildlife management, and social services (e.g., Huntington et al., 2011; Meek et al., 2011; Shanley et al., 2013). Alaska provides half the nation’s commercial

Knowing that there will be a region with persistent summer sea ice poses many challenges: As there is less and less ice, forecasting the location of the sensitive region will become more important (Lovecraft and Meek, 2010; Meek and Lovecraft, 2011). How large will it be, and for how long? How will the ice characteristics change over time (i.e., from multiyear ice to mixed multiyear and first-year ice, to largely first-year ice)? How much and what types of ice are needed to support key species, such as polar bears and ringed seals? Projections indicate that the refuge will be located largely within the exclusive economic zones of Canada and Greenland, but research indicates that the ice supplying it will come from the central Arctic, and with increasing ice speeds (Kwok et al., 2013; Rampal et al., 2009), from the Siberian continental shelf (Pfirman et al., 2009). Given the dynamic nature of the ice cover, what issues are raised by oil development, commercial shipping, and tourism? What would be needed to manage this special region—at local, national, and international scales—so that the quality of habitat is maintained for as long as possible? Will this become a region of cooperation, for example, designated internationally as a special area (Lovecraft and Meek, 2010; Meek and Lovecraft, 2011; Pfirman et al., 2008) or will it become a region of conflict? Establishment of public-private partnerships (see Chapter 4) may be the key to co-management of this region.

This is not the only region in the Arctic that is special; other refugia for cold-dependent species and hotspots are important because of either their vulnerability or their resilience in the face of change, and they need to be managed carefully. How do we predict and then set research and management priorities for regions of high ecological and cultural importance?

fish catch by weight (NMFS, 2012), holds vast reserves of oil and natural gas, is home to indigenous peoples who continue traditional practices on land and sea that are critical to culture and community, serves as a bellwether for rapid environmental change and its impacts, and has a critical role in the regulation of global climate (Euskirchen et al., 2013). The management of Alaska’s fisheries is recognized around the world for its commitment to sound stewardship based on sound science. The regulation of oil and gas activities relies on scientific understanding to uphold the high standards needed to meet the nation’s commitment to conservation of wildlife and ecosystems. Natural and social scientific research supports the pursuit of sustainable futures for Arctic communities.

At the same time, research designs in general are not crafted with decision support for practitioners in mind, and many scientists are ill-prepared to engage substantively and ethically with these processes (e.g., Sutherland et al., 2013; Tyler, 2013). The role of research leading to action with knowledge is complex. Knapp and Trainor (2013) compiled results from a wide range of stakeholders on ways to improve this science-policy link. They found that there is strong decision-maker support for making improvements. Their results are consistent with this report: Among other recommendations, they suggest improvements to broad access to data, knowledge sharing and mobilization, regional scale and community-engaged science, and interdisciplinary research training.

Because of the interdisciplinary nature and the geographic focus of Arctic research, the scientific community is well poised to improve knowledge mobilization and its integration in governance and institutions. It is critical in this time of rapid change, as opportunities for economic development, capacity building, and ecological conservation interact, that Arctic research seeks and implements best practices in supporting knowledge integration in governance. These practices need to address the boundaries between policy-relevant science and policy making (Turnpenny et al., 2013), actively consider the timescales on which decisions are made (Tyler, 2013), and produce knowledge that is, and is perceived as, salient, credible, and legitimate (Cash et al., 2003). In times of rapid change, all of these characteristics can be challenging and thereby prevent scientific knowledge integration or delay policy implementation (Tonn et al., 2001).

Providing useful information for Arctic communities is a good example of the importance and difficulty of connecting research to action (e.g., Gerlach and Loring, 2013). The current and future well-being of those communities depends on, among other things, the ability to respond effectively to the myriad social and environmental changes that are happening. Information is one part of this equation. Human capacity to act on that information is also required, from individual ability to systems of governance that foster adaptation and learning. Collaborations with researchers have great potential to help, but community ownership of both the process and the results is essential. Communication with other communities can help share ideas and successes, building a network of support. These outcomes require understanding of the ways communities operate, and they also need input beyond that which researchers provide. In other words, research and researchers can be part of the solution, while supporting and expanding the community’s capacity to learn and act (Audla, 2014).

The bottom line is this: How can we do a better job of initiating, supporting, and conducting research that seeks to incorporate salient, legitimate, and timely scientific advice into Arctic decision making? Funding agencies that collaborate to produce op-

portunities that incentivize the integration of curiosity-driven and problem-oriented research will motivate such research.

Second, how can we help to promote incorporation of decision support in the broader research community? In the United States “many public agencies still advocate the traditional approach best characterized by the phrase ‘invite, inform, and ignore’” (Karl et al., 2007). There is growing awareness that consultative processes are more effective, particularly in the Arctic context of high costs of field programs and a mobilized and knowledgeable resident community. To maximize opportunities for knowledge integration in decisions while ameliorating the potential for conflict and violations of intellectual property, research programs require decision-maker participation, support for local research capacities, and investments in education and capacity building.

Decision making based on scientific knowledge tends to be more effective when the stakeholders and researchers communicate at all phases of the process: from planning to knowledge generation to assessments of the effectiveness of the decision. Funding of this sort of work, therefore, should include activities that foster engagement among the various entities involved.

Connecting research with decisions is in many respects beyond the capacity of an individual researcher or project. What is needed is more support, both from agencies that fund research and from agencies that make decisions that could benefit from the results of such research. Although short-term decision needs cannot drive all aspects of Arctic research, neither can they be ignored. And although scientific results are not the only factor considered in decisions (e.g., Tyler, 2013), they are an important component, and the Arctic research community as a whole needs to acknowledge the importance of communicating and working with decision makers. We urge scientists and decision makers to look for models to emulate and to work together to find new ways of understanding one another, for the long-term benefit of the Arctic and its inhabitants.

Addressing the challenges that stem from what is happening in the Arctic in the Anthropocene requires a greater degree of cooperation, both among researchers from different disciplines and between researchers and decision makers. In other words, getting more from Arctic research may best be pursued by enhancing the ways in which we make use of that research. We need to support more collaboration among scientists and among nations. We need to improve the application of results by society by creating more ways to interact and fostering a sense of shared purpose to manage change to the best of our abilities. The United States has the resources to invest in such a range of research undertakings throughout the entire Arctic. A will to apply the results of research is needed, as is a continued commitment to studying what exists, what is emerging, and what awaits us in the Arctic.