Technologies are changing even faster than the hearing health care system is, and in many ways technologies are driving changes in that system. Four speakers at the workshop provided both wide-angle and more narrowly focused perspectives on these changes, including the regulation, standardization, and assessment of technologies.

Cynthia Compton-Conley Compton-Conley Consulting

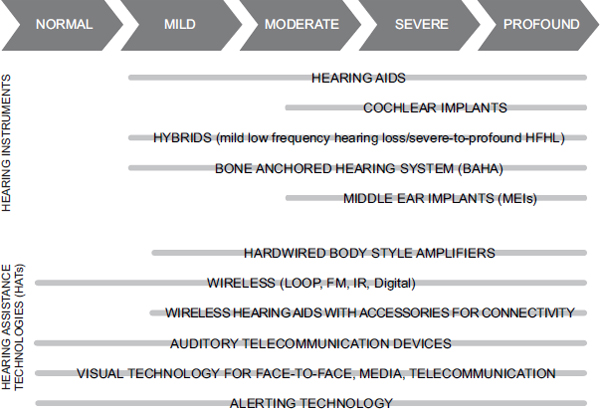

As Cynthia Compton-Conley, chief executive officer of Compton-Conley Consulting, described in an overview of hearing technologies, a wide variety of hearing instruments and hearing assistance technologies are available for people with mild to profound hearing loss (see Figure 5-1). All have become more powerful and sophisticated over time.

Nevertheless, hearing aids and implants do have limitations. First, when microphones are worn on the head, speech understanding is negatively influenced by room acoustics. The target signal, whether speech or music, can become too soft, can be covered up (masked) by noise, and can be smeared by reverberation. Often a combination of these deleterious effects occurs. Directional microphones can improve understanding in some settings, but not in all.

Second, some of the technologies do not work for media such as iPods or telephones. For example, hearing aids and implants need additional ac-

FIGURE 5-1 Range of types of hearing instruments and hearing-assistance technologies available for people with normal hearing to profound hearing losses.

NOTE: FM = frequency modulation; HFHL = high frequency hearing loss; IR = infrared.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission, Cynthia Compton-Conley © 2013.

cessories to provide private listening to music with an MP3 player. In addition, some hearing aids, if held near certain cell phones, will buzz, requiring additional technologies to enhance communication.

Finally, technologies do not always warn people about convenience sounds, security sounds, or other cues. In the past, said Compton-Conley, people only had one ringtone. Now they may have 10 ringtones plus many other sounds alerting them to things that need to be heard or done.

Communication Needs

All people have four receptive communication needs, Compton-Conley said—face-to-face, media, telecommunications, and alerting—and all four of these needs must be met in various venues of a person’s life, whether at home, work, school, play, or volunteer sites. In each venue, an existing technology may need a slight modification, or an entirely different technology may be needed.

One approach to deal with these shifting demands is through a partner-

ship between personal hearing instruments and hearing assistance technologies, said Compton-Conley. Such partnerships can extend the improvement in communication that modern hearing aids and implants make possible. These approaches can be classified into the categories of personal versus private, portable versus stationary, and hardwired versus wireless. With face-to-face communications or the reception of media, for instance, a microphone or other device can pick up a signal and transmit the signal to a receiver that is coupled to a hearing aid or implant, which Compton-Conley described as “binoculars for the ears.” An example is the common portable FM system, in which a microphone/transmitter picks up a signal and transmits it wirelessly to a receiver coupled to a hearing aid, implant, or set of headphones. The selection of coupling depends on the person and situation and would need to be determined through a needs assessment process.

This approach has many different applications and associated technologies. For example, a television may connect wirelessly to a Bluetooth transceiver that then sends the signal wirelessly to a hearing device. Or a signal may travel directly through a wireless connection from a lapel microphone or television to a hearing aid. Such systems can also be used in the workplace, though things can become complicated if more than one employee has a hearing loss and each uses a different wireless hearing aid system, Compton-Conley noted. In some settings where it is important that a signal not leave the room, infrared or encrypted FM transmission can be used.

Compton-Conley also described induction loops, which can be used in many settings. A loop of wire goes all the way around a room and is connected to an amplifier that is plugged into a television or other signal source. As soon as a person walks into the room, a signal is sent to a telecoil inside a hearing aid or implant. “You can loop a table, a chair, an office. This room [where the workshop was held] was looped.” FM transmitters are also used in public places such as theaters or schools to send signals to hearing devices. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), for example, theaters and other public venues are required to have acoustic and inductive coupling.

These systems are far from perfect, Compton-Conley said. People going into a theater hand over a driver’s license and are then given a receiver with a neck loop when they really wanted one with earphones. Patrons may also discover that the receiver is dead, so the manager needs to find a new battery. The signal may be intermittent or the volume control broken. “The manager says, ‘I don’t know what to tell you. We are in compliance. We are following the law.’ He gives you your money back, he gives you your ID back. [But] you are really unhappy.”

Then again, such systems can work perfectly, as in the case of a venue that has been looped according to the standards of the International Electrotechnical Commission. In this case, if the listener’s telecoils are perfectly

programmed, then all the listener needs to do is purchase the ticket, walk inside the venue, and flip the hearing aid to telecoil (or MT [for microphone and telecoil]); the listener can then enjoy the show.

A new technology known as frequency-hopping spread spectrum is portable and has the same coupling options as FM. It can be used for one-way or two-way communication and for small-group or large-group settings. “I did a setup one time where there was a Spanish-speaking tour guide speaking to a hard-of-hearing Spanish-to-English interpreter to a group of hard-of-hearing and normal-hearing people who needed to talk back to the tour guide through the interpreter,” Compton-Conley said. What is needed is to assess the needs of the group and set up rules of communication. “It is a mix of technology and training,” she noted. “You can’t solve problems with just technology. People have to know how to use it.”

These many options can seem confusing, Compton-Conley acknowledged, and they can be even more confusing to older people. Systems can be incompatible, and each person’s system must be adjusted to achieve the best signal. Systems requiring receivers also need to be maintained, and hearing aid or implant users need telecoils to access public systems.

Telephones and Alerting Devices

Many different systems also exist to access phones and other telecommunications systems, including add-on amplifiers, hands-free interfaces, and speech-to-text services. In addition to many varieties of hardwired and wireless systems, live captioning is available for phones or teleconferences either by itself or in addition to auditory input. Some people use automatic voicemail transcription services so that voicemail is received as a text or an e-mail. Specialty professional devices such as amplified or visual stethoscopes are also available.

Finally, Compton-Conley covered alerting devices for homes, offices, and public areas, including alarm clocks, doorbells, phones, crying babies, appliance alerts, weather alerts, motion detectors, smoke alarms, and security alarms. These systems, too, can be hardwired or wireless, and they can use an auditory signal, a tactile signal, or both. For example, Compton-Conley once set up a pressure mat for a woman with Alzheimer’s disease so that if she walked out of her bedroom in the middle of the night, the bed of her severely hard-of-hearing daughter and son-in-law would shake. Similarly, a gateway (transceiver) device worn at the waist can pick up a signal from an alerting device and then cause a hearing aid to beep as well as flash lights around the home.

Fire safety is a particular concern, given that individuals older than age 65 have a fire death rate more than twice the national average. Most current smoke detectors have peak sounds at about 3100 hertz, which is right

where many older people have hearing loss. When people are asleep, the alerting signal needs to be about 40 dB louder than when they are awake, Compton-Conley said. Also, many people with hearing loss incorrectly assume that they will be able to hear a smoke detector because they can hear it when they test it. “If you are in a deep sleep, on medication, are sleep deprived, or [have your head] under your pillow, and your smoke detector is behind a closed door, you might not hear it.”1 “Fire safety alerting systems for individuals with hearing impairment need to be recommended more often,” she said.

Disruptive Technologies

Companies are beginning to explore disruptive technologies that could change the paradigm, Compton-Conley reported. First-generation devices are being developed that can stream virtually any signal from a smart phone to wireless hearing aids. People would still need telecoils for large public areas, but eventually signals could be available from such areas that go directly to phones and then to a hearing aid, avoiding receiver maintenance and coupling issues.

Another disruptive technology would be a chip built into hearing aids that could convert signals from any model of hearing enhancement device. Similar sorts of universal design technologies could meet all four hearing needs while also providing hearing protection. Research is under way on self-fitting hearing aids that measure hearing thresholds, create an on-the-fly prescription, and fine-tune a device over time to meet a person’s listening needs. And smartphones could eventually be used as hardwired universal hearing enhancement devices.

The critical question, said Compton-Conley, is what consumers want and need and how best to meet those needs. One obvious thing they want is full communication access for a lifetime, which requires a holistic needs assessment process, including careful assessment of residual hearing using best practices, speech, and noise testing. This assessment process would look at a person’s health, situation, finances, and comfort with technology which would yield a customized set of technologies and training that are verified and validated. “People make the mistake of jumping into the technology before they analyze the needs,” said Compton-Conley. “Or they analyze the needs, they recommend the technology, and they don’t program the telecoil, for example. This needs to stop.”

Compton-Conley concluded with several ideas that she said should be

____________________

1 Specific information related to fire safety may be found at www.soundstrategy.com/tutorials/how-alerting-technology-can-keep-you-and-your-family-safe-and-add-convenience-yourlife (accessed February 26, 2014).

adopted to meet existing challenges. First, she said a required sequence of coursework for hearing health care providers is needed that is standardized across training programs and focused on best practices, along with more rigorous accreditation. She also recommended an open-platform universal design that provides simplified selection and fitting, easier consumer access, and minimal maintenance for venues; instructional applications for personal and public access, including an assistive listening devices locator; and a massive informational campaign, including a checklist for consumers. She added that continued research and development is needed on self-fitting, self-adjustable, open-platform devices. Finally, Compton-Conley supported an open market for both prescribed and nonprescribed hearing enhancement products.

In conclusion, Compton-Conley recalled an elderly patient who came in with his son and his wife of more than 60 years. He had brain stem injuries due to repeated strokes, and hearing aids were not an option. He was also in a wheelchair and had visual problems, so captioning was not an option for him. During the case history, he was unresponsive, so Compton-Conley gave him a set of earphones attached to an FM receiver. When she talked into the microphone connected to her own FM transmitter, Compton-Conley said, the patient “perked up.” She asked him what he had for breakfast, and he answered with animated detail. Compton-Conley said his wife and son were amazed. The man lived 5 more years and was able to communicate easily with his wife, son, and extended family. He was also able to listen to the television, as well as hear his wife, by using the FM receiver equipped with a direct plug-in to the television and a remote microphone placed on the table between him and his wife. Compton-Conley said this case illustrates the importance of assessing a person’s needs first and then applying appropriate technology and training. It also points out that a range of technologies is available to provide communication access.

Eric A. Mann U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) derives its regulatory authority to oversee the safety and effectiveness of medical devices from the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which specifies in section 201 that a medical device is intended to diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent a disease or condition, or is intended to affect the structure or function of the body, and does not achieve its intended use through chemical action or metabolism. This is a very broad definition, said Eric Mann, clinical deputy director for the Division of Ophthalmic and Ear, Nose, and Throat Devices

in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the FDA, but “it does draw a bright line between things that are medical devices and those that aren’t.” By this definition, a hearing aid is clearly a medical device. In contrast, a personal sound amplification product (PSAP), in the FDA’s view, is a product meant to be used by normally hearing people under certain listening conditions. Thus, the FDA distinguishes between a hearing aid, which treats hearing-impaired consumers of any degree, and a PSAP, which is for normally hearing individuals. The FDA recently updated a guidance document in draft form to clarify the types of claims that would be associated with hearing aids and with PSAPs.

Because a huge range of devices fall under its purview, from tongue depressors to pacemakers, the FDA applies a risk-based classification in which the regulatory requirements are matched to the risk posed by the device. Class I devices are considered low risk; Class II, moderate risk; and Class III, high risk. For Class I devices, baselines levels of regulatory requirements that apply across all device types are intended to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the device. For Class II devices, additional special controls are needed, such as a performance standard, points that need to be addressed in a premarket submission, or a postmarket surveillance requirement such as a registry or a device-tracking mechanism. Class III devices must undergo a premarket approval process, which generally requires a well-designed clinical study and information on manufacturing.

Different kinds of hearing devices fit into different categories. A typical air conduction hearing aid is considered a low-risk Class I device. Class II devices include such devices as bone-conduction hearing aids, bone-anchored hearing aids, and tinnitus maskers. Wireless air conduction hearing aids can also be Class II devices, not because of risks from the hearing aid but because of the regulatory controls needed to ensure their effectiveness given wireless interference and other issues. Class III auditory devices include technologies such as cochlear implants, implantable middle ear hearing devices, and auditory brain stem implants.

Mann focused most of his remarks on Class I devices, because they were the focus of the workshop. For these devices, the FDA has determined that general controls in and of themselves are sufficient to ensure safety and effectiveness. General controls include the following:

- The prohibition of adulterated or misbranded devices so that labeling is not false or misleading

- The use of good manufacturing practices

- Registration of manufacturing facilities and listing of device types

- Record-keeping requirements

- Provisions for repair, replacement, and refund (though these rarely come into play, said Mann)

When the medical device amendments were first enacted in 1976, there was a requirement for premarket notification, also known as a 510(k), for Class I devices. Since the late 1990s, most Class I devices have been exempt from that requirement for premarket notification. Thus, as long as they comply with the general controls, the manufacturers of air conduction hearing aids would not have to submit a premarket application to the FDA. The exceptions, said Mann, would be if a fundamental change in technology to the hearing aid occurred or if the hearing aid were being indicated for a new population, which would exceed the limitations of the exemption and would require a 510(k).

Provisions for Hearing Aids

A handful of devices at the FDA have separate regulations to ensure their safety and effectiveness, and hearing aids are among those devices. One regulation governs labeling (21 CFR 801.420); another governs the conditions for sale (21 CFR 801.421).

For labeling, the regulations require hearing aid manufacturers to develop a user instructional brochure. The regulation outlines the content of that brochure, requiring, for example, well-defined instructions for use and notification that the hearing aid will not restore normal hearing. A “Warning to Hearing Aid Dispensers” lists what are often referred to as “red flag signs and symptoms,” such as draining from the ear or asymmetric hearing loss. An “Important Notice for Prospective Hearing Aid Users” describes the conditions for sale and the need for a medical evaluation. A technical performance data section is also required as defined by a standard from the American National Standards Institute (ANSI).

For the conditions for sale, the regulations require a medical evaluation by a licensed physician within the preceding 6 months of dispensing a hearing aid. A waiver of the medical evaluation is possible for users more than 18 years of age as long as the patient signs a statement acknowledging that a medical evaluation is in his or her best health interest. The dispenser may not encourage the waiver, and the dispenser must afford patients an opportunity to review the user instructional brochure. Record-keeping requirements for 3 years are also specified.

Both of these regulations were the product of recommendations from an interdepartmental task force and U.S. Senate hearings that were held in the mid-1970s to look into the suboptimal diagnosis and treatment of hearing disorders prior to dispensing a hearing aid, as well as the marketing of hearing aids to vulnerable individuals who did not need them. The regulations are based not on safety issues with the hearing aid but on recognizing medically and surgically treatable causes of hearing loss and providing optimal hearing health care for patients, said Mann.

Discussion

As Mann said, if a PSAP were to make claims about treating hearing-impaired individuals, then it crosses the line and meets the definition of a medical device. The FDA could then take enforcement action to require conformance with the medical device regulations, including the specific regulations for hearing aids.

Frank Lin pointed out that PSAPs are linked with issues of access. Many people do not have enough money to buy a hearing aid. Access to some type of rudimentary PSAP device could improve their lives. “In the field of audiology and acoustic sciences, there is always the pursuit of perfection. We want the absolute best.” But often the best is not necessary, Lin observed. “The way we approach hearing health care right now is that you either have everything or you have nothing.” The gap between a PSAP and a hearing aid is essentially narrowing to nothing, he said. “It is how you market it and how you label it.” Lin argued that something is better than nothing. “My question is, what can we do, from a regulatory point of view, to make access to such devices possible?”

Mann responded that the FDA does not distinguish between a rudimentary hearing aid and a more advanced hearing aid. The regulations define a hearing aid as a wearable instrument that is intended for hearing-impaired individuals. He also pointed out, however, that the regulations are not incompatible with a direct-to-consumer marketing model, as long as the labeling requirements are met and a waiver is signed. “We have been fairly liberal in terms of interpreting this,” he said. “As long as the patient has the opportunity to review the user instructional brochure, and as long as the record-keeping requirements are complied with, a manufacturer can directly market to a consumer.” Many people are using these waivers, he acknowledged, but signing the waiver could be of some benefit to patients by informing them of conditions that could be treatable. If a hearing aid then does not solve their problem, or if they encounter progression of their hearing loss, they may be more likely to see a physician as a result of that counseling process. “It is a complicated issue,” he said. “We are willing to listen to different perspectives on this. There certainly is a process—kind of a cumbersome one—to change regulations, but it exists.”

Still, he also noted that hearing aids are different from reading glasses, where it is much easier for individuals to self-diagnose their conditions and to decide whether magnifying eyeglasses are an appropriate solution for their particular health situation. Hearing loss can result from a large variety of serious health conditions that could potentially be detected by a medical evaluation, Mann said.

Stephen Berger TEM Consulting

Standards are tools that can serve a variety of purposes, said Stephen Berger, president of TEM Consulting:

- They can be multiparty contracts.

- They can be vehicles for knowledge transfer.

- They can be specifications to ensure different kinds of interoperability.

- They are a vehicle for facilitating conformity assessment and management.

- They can be a tool for technology planning.

Berger described each of these purposes in turn.

Multiparty Contracts

As an example of a multiparty contract, Berger cited the ANSI C63.19 standard governing the compatibility of hearing aids with mobile phones. The standard, on which work started in 1996, is mandated by the Federal Communications Commission and recognized by the FDA. “In general, we have been successful,” said Berger. “Obviously, we didn’t get it perfect out of the box. We are on standard version four and are actively talking about what we might need to do in version five. Also, in both industries, technology has changed.”

One lesson learned from this experience is that consensus is almost impossible when costs and consequences are not aligned. It is not unusual to encounter a circumstance where if one industry were to pay a little more, another industry would benefit. But “how are you going to make that happen?” asked Berger. “It is not easy.” At the beginning of the development of the C63.19 standard, both industries, which are quite different, accused the other of being the source of the problem. The impasse was broken when one of the phone companies sent several engineers to a hearing aid chip manufacturer to show how to make a chip immune from interference. This gave the chip manufacturer and any phone company that bought the chips a way to differentiate their products from those of their competitors. “All of a sudden, market forces started kicking in,” said Berger. “We got a consensus and finished the standard.”

Knowledge Transfer

This process created a lot of knowledge transfer, said Berger. Bodies of experts exchanged knowledge and sought to understand each other’s landscape enough to find consensus solutions. That is happening today in the hearing aid industry as the move to digital technologies shifts attention from simply raising the volume of sounds to issues of signal quality. Similarly, the standard for radio frequency interference is now based on the amount of interference created in the hearing aid rather than just the amount of potential interference from radio frequency sources.

Interoperability

Different kinds of interoperability exist. One is simply that if two devices are close together, they do not interfere with each other’s operation. Another is that two devices may rely on different equipment, but their measures and outputs mean the same thing. A third is that units from different vendors work with each other, either for core functions or for all functions. Achieving interoperability can have both positive and negative effects, said Berger. For example, bringing people together to create interoperability can have the effect of stifling innovation.

An effective feedback system is almost always necessary to create interoperability, Berger said. If laboratories do not test a device properly, even a wonderful standard will not produce a desired outcome. Similarly, market experiences typically need to feed back into a standard to get the outcomes sought by the standard.

Conformity Assessment and Management

Conformity assessment and management help ensure that products meet their specifications in actual use. The people who wrote a standard know what they had in mind, but the standard needs to be translated to ensure that requirements lead to the right outcomes. If this is done properly, good products get through, and those that are below par get returned for further work. In this way, standards can also facilitate market forces. When consumers do not know how to distinguish an excellent product from a poorly designed product, they cannot make informed choices.

Technology Planning

Finally, standards further technology planning by helping to keep industries synchronized, he said. Thus, as the cell phone industry moves to the fourth generation, standards enable the hearing aid industry to remain

synced with changes in cell phones. Also, different technologies require different metrics, as demonstrated by the history of audio quality standards. And a particularly difficult challenge is how to “end-of-life” a technology and move to a better solution, said Berger. “How do we give incentives for people to move to a new and potentially much better solution while not leaving people isolated and orphaned with what had been the previous solution? It is something we need to map out, or else our regulations end up becoming anti-innovative, which is not where we want to be.”

Interesting work is going on in understanding the relational links between seemingly unrelated areas, Berger noted. The task is to map and then manage the complex ontology surrounding hearing loss. “Most of what we have been talking about is trying to understand what is this ontology that we are all working at? What are the dynamics? What are the relational links? How do we manage it to get to a better future?” Understanding the types of innovation would shed light on this ontology. For example, are innovations disruptive, sustaining, or obstructive? What are both the intended and unintended consequences of innovation?

Standards are not a panacea, Berger asserted. They are “great when they are the right tool for the job. They are lousy when they are mismatched or just a feel-good exercise.” Standards can have the effect of suppressing innovation, and regulators and standards developers need to minimize that possibility. Therefore, both standards and regulations must focus on the required outcomes while being slow to dictate methods for achieving those outcomes. Another challenge is to move from a consensus that has been right for the past to one that is right for the future. Still, standards can also document a multiparty consensus, and “when they do that well, they can be really powerful,” Berger concluded.

HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT: ROLE IN TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT AND USE

Fiona A. Miller University of Toronto

Health technology assessment (HTA) is a field of applied policy analysis designed to support decisions about payment for health technologies, including drugs, devices, diagnostics, procedures, and even different ways of organizing health care. It is “an evidence-informed and a value-laden enterprise that plays an important and growing role in determining what kinds of technologies and services will be available for patients within health care systems,” said Fiona Miller, associate professor of health policy at the University of Toronto’s Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation. It is also increasingly being used to support technology development.

Miller pointed out that, in modern health care systems, health care is not primarily financed through payments by users for their own care. Rather, health care is primarily financed through collective payment mechanisms, whether public or private. The United States is not an exception to this observation. For example, out-of-pocket expenditures on care as a percentage of total health expenditures is actually lower in the United States than in Canada, even though Canada has a single-payer system. “The vast majority of health care is provided collectively,” said Miller. “We pay for each other’s care, not so much for our own.”

Of course, the coverage of hearing aids and other hearing-related technologies, as pointed out by other speakers, varies. The province where Miller lives provides substantial coverage of these technologies, whereas coverage is much more limited in the United States. These coverage provisions can be important, she pointed out, because small things can have a major impact on healthy aging. As people age, hips, knees, and hearts are important, but so is support for living at home, transportation, and meals, said Miller. Supports for simple things like clearing the snow or picking up groceries can help older adults to avoid a fall and the subsequent need for long-term or rehabilitative care. “These are the types of small things that enable people to age healthfully.”

Hearing aids are among the small things that matter, Miller argued. People with chronic and debilitating conditions are by far the largest source of health care expenditures, but most people can be supported through self-care and low levels of supportive care. To the extent that hearing technologies can support healthy aging and avoid the need for higher-cost technologies, they can be an important part of the health assessment conversation.

The Development of the HTA Field

HTA emerged in the United States in the 1970s but is now well developed internationally. The International Network of Agencies for HTA now includes 57 member agencies from 32 countries. In the United States, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality is a major supporter and conductor of HTA.

A basic premise of the field is that “newly approved” does not always mean new or improved. Health technology regulations ask whether a technology is safe to have on the market, at least for a specific class of patients. HTA asks different questions: Is technology safe and at least as good as the alternatives in the real world? Also, is it worthwhile to invest in this technology?

Today, HTA has a variable role in health care systems, Miller observed. In some health care systems, it is still fairly detached from coverage. It pro-

vides guidance but does not necessarily guide coverage decisions. In other health care systems, it does directly inform coverage. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom reviews technologies and decides whether they will be provided and covered. Within each Canadian province—each of which essentially has its own health care system—health technology assessment often has a fairly close link to the decision to cover a technology. Sometimes the procedure is even more embedded in decision making. In Canada and some European countries, a movement has gained momentum to locate HTA within a regional health authority or hospital to inform decisions on investments within annual budgets.

Forms of Evidence

HTA involves different kinds of evidence. The most important is clinical evidence, which includes the evidence of safety and efficacy that a regulatory authority would demand, as well as evidence of real-world effectiveness and comparative effectiveness. “We want to know how [a new technology] compares to the existing best-case scenario, or at least to another technology or package of services that is being used.”

Another form of evidence is economic. Because health care is primarily paid for collectively, the question is whether a new technology represents a good use of limited resources, in recognition of the opportunity cost of not investing in the next best alternative. “If you bring in five new technologies that cost X, something has to give.” Although the United States has resisted taking this step, said Miller, Canada and most of Europe have been more willing to look at the economic evidence. Value for money, the impact on budgets, and affordability are all relevant issues.

HTA also takes patient and social values into account. It looks at patient preferences, health equity, and transparency and clarity in the actions of agencies, which Miller referred to as “accountability for reasonableness.” Obviously, it is a “fraught and complex exercise,” she said.

HTA Experiments

Historically, HTA has focused “downstream” on the implications of novel technologies for health and health care, assessing whether health technologies warrant adoption; accordingly, HTA has often been seen as a barrier to innovation. Increasingly, however, HTA is looking “upstream” at innovation processes, seeking to support decisions about the design and development of emerging technologies; from this perspective, HTA has a role as a facilitator within productive health innovation systems. Miller described three types of experiments taking place around the world that

position HTA as a facilitator of health innovation. In the United Kingdom, for example, the emphasis has been on innovation adoption. Thus, where a technology is seen to merit investment, concerted attention is given to ensuring that it is used equitably and broadly across the appropriate populations.

A second experiment involves harmonization of evidence requirements across HTA agencies or between regulatory agencies and HTA agencies. With hearing aids, for example, would it be possible to align the evidence that regulators want with the evidence needed for HTA? This question has been much discussed in Europe and elsewhere, Miller reported.

A third experiment involves “early” HTA, where technology assessments are conducted early in the development process to inform technology design and provide decision support for industry. Early assessment helps industry to learn sooner whether a technology will meet the expectations of payers: “Fail fast and fail early if you are going to fail,” Miller said. In Ontario, for example, an initiative with which Miller is involved, called MaRS EXCITE,2 seeks to be a single portal for evidence generation and review early in the design and development phase. “We are working with large multinational enterprises, but also small and medium size enterprises, that sometimes have no idea in the design and development phase what they will need to show to justify payment by Ontario’s health care system.”

HTA can play an important role in analyzing the merits of health care investments, Miller concluded. It can provide both a guide and an incentive for supporting technological innovations that will improve health, including technologies relevant to hearing loss.

In response to a question about whether the demands of regulators and HTA agencies for evidence of safety, efficacy, and effectiveness might stifle innovation, Miller pointed out that this is “the classic countervailing powers question.” Perhaps a small mom-and-pop shop will not be successful, she said, but the question is, do we want the small mom-and-pop shop to be successful if that means items that did not pass any meaningful regulatory hurdle are on the market? For instance, the pharmaceutical industry no longer has mom-and-pop companies as it did at the end of the nineteenth century. The merger of companies is, in part, a response to the regulatory and HTA environment. These demands reflect the reasonable expectation that innovative health technologies will be safe and effective and will address genuine and important health needs.

____________________

2 See http://excite.marsdd.com (accessed February 26, 2014).