As is occurring in other major sectors of society, innovation is reshaping the hearing health care system. New technologies, new ways of delivering hearing health care, new policies, and new ideas about design are changing how people access, use, and pay for hearing devices. This chapter brings together five presentations at the workshop that examined these innovations, which together have the potential to transform how people around the world confront and overcome age-related hearing loss.

THE COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKER MODEL1

Prepared by: Nicole Marrone, University of Arizona Presented by: Theresa Chisolm, University of South Florida

Community health workers are front-line public health workers who are trusted lay members of the community they serve, observed Theresa Chisolm, professor and chair of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at the University of South Florida on behalf of Nicole Marrone, assistant professor and James S. and Dyan Pignatelli/Unisource Clinical Chair in Audiologic Rehabilitation for Adults at the University of Arizona. Community health workers serve as a liaison or intermediary between health or social services and the communities to facilitate individuals’ access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of

____________________

1 This presentation was written by and based on the work of Nicole Marrone, but presented on her behalf by Theresa Chisolm.

service delivery. They have many titles, including community health worker, community health advisor or aid, promotora, community health representative, peer health promoter, lay health educator, and patient navigator. Their core competencies include communication, interpersonal skills, service coordination, capacity building, advocacy, teaching, and organizational skills. They provide cultural mediation between communities and health and human services systems, advocate for individual and community needs, and ensure culturally appropriate health education and support.

Community health care workers do not provide clinical care and generally do not hold professional licenses. Nevertheless, they have expertise about the communities they serve because they share cultures and life experience with the members of those communities. They rely on relationships and trust and relate to community members as peers rather than purely as clients or patients.

Previous research has shown that community health care workers can improve access to care, enhance successful chronic disease prevention and management, improve the use of health services (such as reducing the inappropriate use of emergency rooms), help to control costs, and produce a positive return on investment (Ingram et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2012; Reinschmidt and Chong, 2008; Sabo et al., 2013; Staten et al., 2012; Viswanathan et al., 2009). Research has also demonstrated their effectiveness in addressing health disparities for minority populations, increasing health care utilization, providing culturally competent health education, and advocating for patients’ needs (Rosenthal et al., 2010).

Chisolm said that according to Marrone, collaboration with community health workers may be a way to reach people in the community who are otherwise not seeking audiological services. Among Hispanics, for example, far fewer of those who could benefit from hearing aids use themas compared with hearing aid use among the general population. To address this disparity, Nicole Marrone and her colleagues at the University of Arizona are developing a community health worker intervention adapted from her current community-based audiologic rehabilitation program to identify untreated hearing loss in the Hispanic population. Results from that intervention showed that of the adults tested in the community, approximately 76 percent of this urban sample had hearing loss but never had access to care. The program has placed some of these individuals into Spanish-language community-based audiologic rehabilitation groups, which were compared with a group of English-language audiologic rehabilitation participants. Preliminary analyses found that both groups showed improved outcomes in terms of enjoyment of life and daily use of communication strategies even without the use of hearing aids.

As the population ages, all groups will have a growing prevalence of chronic health conditions, including hearing loss. In addition, there are

social determinants of health that affect different groups in different ways. Marrone wrote that achieving the goals of Healthy People 2020 requires a commitment to reduce health inequities across all populations, Chisolm observed.

In collaboration with community providers and community health workers, Marrone is seeking to identify barriers and resources in the community and collaboratively develop an efficacious community health worker intervention in a rural community that is generally underserved and facing great health disparities. This effort includes the development of culturally and linguistically relevant materials and testing of a community health worker model of intervention for older adults with hearing loss. Extensions of this research could evaluate the effectiveness of this model in other geographic regions or with other populations facing health disparities.

Gabrielle Saunders National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research, Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Teleaudiology is the delivery of audiology services and information via telecommunications technologies, said Gabrielle Saunders, associate director of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation Research and Development National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research in the Portland, Oregon, VA Medical Center. She emphasized that teleaudiology is not a separate subspecialty of audiology. Rather, it is the use of technology as the means to the end of good hearing health.

Telemedicine methodologies can be divided into four categories, Saunders continued. Store and forward technologies collect patient data at a remote site and transmit those data to a health care professional to review. Synchronous or real-time teleaudiology uses videoconferencing or other means to conduct hearing tests, hearing aid fittings, audiologist-directed real-ear measures, hearing aid counseling, tinnitus management, or other services. Remote monitoring involves the patient wearing a device that gathers data that are sent remotely to a health care provider. Finally, mobile health teleaudiology, which is the category on which Saunders focused, includes online auditory training programs, tinnitus management, hearing tests, and counseling. It is patient driven and independent of the practitioner. It also raises the largest unknowns for the field because patients are in charge of the technology rather than specialists.

As examples of successful telehealth programs, Saunders mentioned the Alaska Federal Health Care Access Network, established in 1998, which provides services to patients across Alaska at a great cost savings compared

with personal services. This program has dramatically decreased wait times for appointments and has produced high patient and provider satisfaction. The VA also has a very active telehealth program that includes audiology services, with more than 1.6 million veterans needing services. This program, too, has produced levels of satisfaction with teleaudiology encounters as high or higher as those of in-person encounters, said Saunders.

Mobile Health

Technology has already made it much easier to access a hearing test, Saunders observed. Online hearing tests, hearing applications, and telephone screening can all test a person’s hearing, though each approach raises questions. The first is whether the data are accurate and valid, which at this point is not generally known. “Some of these measures are well designed, and they have been proven to be valid, but not all of them,” said Saunders. False negatives can also be a problem if patients are told that they have normal hearing but in fact have a hearing loss. And whether people understand the results from applications and online tests is unclear. In a face-to-face interaction, the patient can ask a question if he or she does not hear or understand what the physician has said, but that generally cannot be done with remote tests.

The bottom-line question, said Saunders, is whether self-conducted tests motivate behavior change. According to a study conducted in Australia, of 193 individuals who failed a telephone-based screening, only 70 sought help; of the 26 who were recommended hearing aids, only 13 obtained them; and of the 13 who obtained hearing aids, only 6 used them more than 4 hours per day (Meyer et al., 2011). These numbers seem very low, Saunders acknowledged, but similar findings are found with face-to-face screening (Yueh et al., 2010). “The issue isn’t teleaudiology per se,” she said. To overcome these barriers, she noted, the field needs to know more about the attitudes and beliefs underlying hearing health behaviors. In addition, public health messages could be targeted for different age groups to bring awareness of hearing and hearing loss to the whole population, not just to those with increased likelihood of hearing loss.

Assistive Technology

Technology has also made it easier to access hearing assistive technology. Saunders diagrammed some of the distribution systems that exist today for hearing technologies. These include traditional systems (from manufacturer to end user via a private practice), direct distribution (from manufacturer to the end user via a storefront), and semi-direct distribution (wherein a medical doctor and an online hearing aid retailer are involved).

There are also pathways involving online retailers that do or do not also involve local support (e.g., audiologists, other hearing professionals). Most of these pathways involve hearing professionals, but online retailers without local support typically do not. These new models are controversial, she acknowledged, “but they are inevitable, especially with the increased availability of personal sound amplification systems.” The field will need to figure out what role audiologists will play if large numbers of consumers start bypassing their services. “We don’t know yet, so we need to be conducting that research to find out how these alternative models are going to impact outcomes,” Saunders said.

Another way of using technology to acquire hearing assistance is by using a smartphone as a hearing aid. Systematic research will be needed to determine the pros and cons of this approach, Saunders said. Applications and telephone technologies are also available for tinnitus management, with a telephone tinnitus education program for veterans being evaluated in a study at the National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research. In addition, technology permits home-based, online computerized auditory training, as discussed earlier in the workshop. Although large randomized studies have not demonstrated benefits from such training, some people in these studies benefited from the training. If those people could be identified in advance, the training could prove useful for at least a subgroup of the population, though the question remains regarding how much they could benefit.

Technology has also spawned online hearing-related support groups, counseling programs, and other online gatherings. Although little work on the value of these groups has been conducted, one study showed positive outcomes (Thorén et al., 2011).

The willingness of patients and providers to use teleaudiology depends on the applications. For example, Saunders stated that recent data show that audiologists are much more willing to use teleaudiology for answering patients’ questions or for counseling than to fit a hearing aid or assess its performance, and they are less willing to use teleaudiology with patients receiving their first hearing aid than with experienced hearing aid users. The willingness of patients to use teleaudiology varies, with some being not at all willing to use teleaudiology, but more than half of patients being moderately to extremely willing to use it. Opinions change with experience, such that after using teleaudiology to fine-tune a hearing aid, about two-thirds of 16 patients and 8 audiologists were more positive about the procedure, according to data collected by the company Phonak, Saunders said. Use “can change attitudes,” she added, “and that is probably good news for teleaudiology.” Nonetheless, the education of clinicians about teleaudiology will need to be approached carefully, she said, to achieve good outcomes.

Teleaudiology raises many other issues, including technology support,

contingency plans, privacy concerns, patient expectations, patient health literacy, billing, licensing across jurisdictions, and the integration of teleaudiology into daily practice. Nevertheless, teleaudiology has been demonstrated to provide easy access to hearing health care at many levels, Saunders concluded. It is generally acceptable to patients and clinicians and could open up hearing health care to a broader demographic of individuals. “The question is not will teleaudiology happen—it will,” said Saunders, “but how will it happen, and what can we do to ensure it yields positive outcomes for both the patient and the professional?” Answering those questions will require research on usability, effectiveness, and methods for changing hearing health behaviors so that people access the many available options.

Thomas J. Powers Lake Havasu City, Arizona

Thomas J. Powers, a family physician from Lake Havasu City, Arizona, helps his patients to “hear life again.” Powers has a small practice in Lake Havasu City, which has a year-round population of 52,000. His wife manages the office. He has two receptionists and one medical assistant. He has about 7,600 active patients, 47 percent of whom are between the ages of 45 and 64 and 47 percent of whom are above the age of 65. In a recent 6-month period, he and his coworkers screened 767 patients for hearing problems, tested 107, and fitted 47 with hearing aids. Of those 47 patients, 79 percent were new to hearing aids, and 86 percent reported that they would not have purchased or would have delayed purchasing hearing aids because of their cost. “Certainly the cost is a big issue for these patients,” said Powers.

Powers stated that he incorporated hearing testing into his practice because it allowed for more comprehensive care of patients. His medical assistant tests every patient over the age of 40 with a simple hearing test that has four frequencies at 40 dB. In addition, patients fill out a form with a scale from 1 to 10 of how bad their hearing is. If they miss two frequencies and report an 8 or less on the form, Powers recommends that their hearing undergo a more rigorous test. His practice uses an automated pure-tone audiometer with high-quality headphones in a quiet room. Patients fill out a simple form to rule out pathological reasons for hearing loss other than age. If the hearing loss is related to a medical issue—which happens in

____________________

2 Data presented in this section were collected by Dr. Powers from his own patient base.

about 20 percent of cases—the patient is referred to an ENT physician or to a hearing clinic in Los Angeles.

If the hearing test demonstrates a significant hearing loss, Powers fits the patient with a demonstration hearing aid in the office. He then assesses comfort and the patient’s perception of hearing. “We give them time with it. We invite them to go out to the lobby to see what the TV sounds like. We invite them to go outside to hear what the traffic sounds like, the air, the wind.” If the patient decides to purchase a hearing aid, Powers’s wife provides information about maintenance and care and goes over the financial part of the transaction. Powers noted that the simplified yet innovative system enables many of his patients to receive hearing health care quickly and efficiently. He added, “we are not going to treat everybody. But we are at least getting a lot of hearing loss taken care of.”

The screenings generally are not expected by the patient, Powers observed. They are not asked whether the initial screening can occur because many would say it is not needed. “They don’t want to know if they have a hearing loss. They are denying it.” The test, which is conducted as part of the vital exams, is simple and takes only a few seconds. Furthermore, the screenings were appreciated by patients, 89 percent of whom were glad or very glad to have their hearing checked and 72 percent of whom probably or definitely would not have had their hearing checked otherwise.

After testing, 44 percent of the patients who needed hearing aids purchased them. Another 13 percent were referred to other physicians, 16 percent said they were not ready for hearing aids, 3 percent insisted that they did not need hearing aids, and 24 percent said that they could not afford hearing aids. The price of their hearing aids was about $1,500 per pair, and 86 percent of those who purchased hearing aids said that they would not have purchased them elsewhere or would have delayed purchasing them elsewhere because of cost. “There is a lot of denial,” Powers repeated. He observed that it is often helpful to have a spouse present, as patients will deny any hearing difficulties.

Patients were largely happy with their hearing aids, he said. Seventy-two percent were wearing them 8 to 16 hours per day, 14 percent were wearing them 4 to 8 hours per day, and another 14 percent were wearing them 1 to 4 hours per day. Powers makes sure that the hearing aids are comfortable and working, and his wife handles calls from patients. They even do house visits if a patient is older and cannot come to the office. “They are very satisfied, and they are using them.” Powers does not charge for the testing or the fitting. Some patients have a hard time affording the cost, but a credit program is available for those who qualify.

Powers was concerned that the audiologists and the ENT physician in town would react negatively when they heard that he was dispensing hearing aids. But he said that has not been the case. He needs audiologists and

ENT physicians so that he can refer more complicated cases to them. He also pointed out that having an audiologist in the office would be one approach, but interaction with a familiar and trusted primary care physician can be especially powerful for a patient.

Powers noted that many of his patients report that the technology has transformed their lives. “We are making conversations with family easier for them. They are going to movie theatres and understanding speech. They are going to the grocery stores and hearing much better. We are making an improvement in their lives.”

The impact on his practice has been minimal, though it does interrupt his schedule somewhat, in that he is seeing hearing aid patients on top of his regular 15-minute-per-patient schedule. But the patients are surprised, grateful, and happy, he said. It also has been rewarding and gratifying to Powers because “it is life-changing to the patients. You put a hearing aid in them and they just wake up.” Finally, it is cost-effective.

“We need to get this into family practice residencies,” Powers concluded. “We need to get it into primary care. I hope that I am just a stepping block for that.”

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE BUSINESS MODELS

David Green Sound World Solutions

The strategic use of technology, price, and quality can change the competitive landscape in favor of the consumer, said David Green, cofounder of Sound World Solutions. Drawing on his experience with eye care programs around the world, Green described how the combination of affordable technologies with cost-effective and efficient service delivery can achieve the social mission of pricing for affordability and accessibility.

Experiences with Treating Vision Impairment

Around the world, an estimated 285 million people are visually impaired, and 39 million of these are blind in both eyes, said Green. The eye care services Green has provided are self-financed from patient fees and do not depend on any insurance reimbursement system. Where there is tiered pricing, “free” is the lowest price, and revenues are used to subsidize care for those who cannot afford a service or can only pay below cost. This creates not only competition in price-sensitive markets but entirely new ecosystems with markedly reduced costs.

Cataracts are the main cause of blindness and have been the main emphasis of Green’s efforts. He has helped more than 300 programs, which

together perform about 1 million surgeries per year, become self-financing. One of the best known is Aravind Eye Hospital in India, which provides more than 370,000 surgeries per year. Green described the hospital’s model where 51 percent of patients get service either for free or below cost. The remainder pay above cost, and the margin is used to cross-subsidize care. Even with this cross-subsidization, Aravind in 2012 was able to make a 33 percent margin.

About 1,500 eye camps are held each year, with community organizers convincing patients to come. A team from Aravind tests vision, and those needing cataract surgery receive patient counseling and are taken immediately for surgery. Those needing refraction receive their eyeglasses immediately after they receive their prescription. If the eye camp is on a Sunday, patients go to the hospital that day, have their surgery on Monday, and go home on Tuesday. This model achieves what Green called his law of propinquity: reducing the time between detection, treatment, and client satisfaction.

Green has also worked with programs in Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Guatemala, Nepal, and other countries, as well as in San Francisco. These programs perform many thousands of surgeries, many for free. For example, the Lumbini Eye Hospital in Nepal has done 47,000 surgeries, 70 percent for $33.00, 20 percent for $78.00, and 10 percent for free, while producing a profit of $220,000. “Nepal is 1 of the 10 poorest countries in the world,” he observed, “and yet Nepal has found a way to serve all with eye care needs and with profit.”

The cost advantage at Aravind is significantly influenced by higher labor productivity and not just lower labor costs, said Green. A cataract surgery that could cost almost $500 in a developed country can be done for just a couple of dollars in Aravind. Even if the prices from developed countries were applied to the Aravind staff, the surgery would cost only about $80.00, “which shows how there is a level of efficiency that has been achieved that the West would do well to emulate.”

Green has also worked with programs to develop affordable products. For example, a company established in 1992 to make intraocular lenses now has about 10 percent of the global market, selling more than 2 million lenses per year. The Aurolab price for a lens is about $3.50, compared with more than $100.00 for its competitors. The company also makes surgical suture and pharmaceuticals for prices far below those of competitors.

By pricing its products for affordability, the company changes the competitive landscape. For example, it still has a 40 percent margin on its lenses. “It has to do with how you sculpt the business model, not only your cost but your margin,” Green said. Furthermore, by providing products for much lower costs that are tuned to the needs of lower-income people, the company increases the use of those products. Cataract surgeries in India

went from 800,000 to 6 million in just one decade, driven by a newly competitive ophthalmic industry. That is “something that you really don’t see in the United States,” said Green. “You don’t really see price competition in the medical system.”

Applying the Model to Hearing

Green is now applying the same model to hearing. The World Health Organization estimates that 360 million people around the world have disabling hearing loss (WHO, 2014). Yet according to Green, only about 7 million hearing aids are sold each year, and only 10 percent of those go to the developing world. These numbers have remained constant over the past decade, Green pointed out, and will remain so unless the industry experiences significant disruption with regard to pricing, distribution, and accessibility to the customer.

Green cofounded Sound World Solutions to provide amplification in real-world environments, easier access, greater availability, lower prices, and simpler processes for buying, fitting, and using the product. The technology platform that Sound World Solutions has devised is a Bluetooth-enabled hearing device that attaches to the ear. A smartphone application provides a 2-minute assessment of listening preferences and programming, and the device can be adjusted using a smartphone or the controls on the device itself. It works with iPhones or with Android-enabled phones and with Apple or PC computers. Green asserted that it has excellent directionality and noise control for both telephone and amplification mode and is the smallest Bluetooth headset in the market. It can be used both as a personal amplifier (with a limited output of 106 dB) and as a hearing aid (with a maximum output of 130 dB with 70 dB of gain). The fit is customized through an assortment of ear tips that are made out of proprietary material to reduce feedback and enable fitting for severe hearing loss without the need for a custom mold. For the behind-the-ear version, the rechargeable battery has a 16-hour life.

Green said the strategy for emerging markets is to work through preexisting programs, such as social enterprise networks, government programs, doctors’ offices, and eye care programs. A training program teaches technicians how to fit the product. As a result, Green and his colleagues are able to reach beyond existing enterprises to enable entrepreneurial growth and increase access to hearing health care. In the United States, the product will be spread to underserved communities through federally qualified health care centers, American Indian clinics, Spanish-speaking clinics, county health departments, and home health care agencies. It is a business model “that makes hearing affordable and accessible to all,” Green concluded.

During the discussion period, a question was raised about the FDA

allowing a self-assessment test on a hearing device tied to the purchase of a hearing aid. Green noted that the test is not conducting a hearing assessment. It is intended to help a person decide on a listening preference. People have access to the controls so they can adjust the device while wearing it in different environments. When sold as a personal amplifier, the output of the device is also limited to 106 dB so that people do not damage their hearing even if they make an error in adjustments.

“We hope to shake things up,” said Green. “We hope that hearing aid companies and audiology will join us in shaping different market forces that serve a much greater number of people.”

Valerie Fletcher Institute for Human Centered Design

The Institute for Human Centered Design is an international education and design nonprofit organization dedicated to enhancing the experiences of people of all ages and abilities through excellence in design. It is based on two core ideas, said Valerie Fletcher, the institute’s executive director. First, design powerfully and profoundly influences everyone’s sense of confidence, comfort, and control. Second, variation in ability is ordinary, not special, and affects most people for at least part of their lives.

Inclusive, universal, or human-centered design is a core concept of social sustainability, said Fletcher. People live longer today than they did in the past, and they have a higher standard of living. Environmental sustainability is also a growing concern and links social sustainability with respect for human diversity and interdependence, with the need for evidence, and with the long view. Inclusive design is built on a base of accessibility. This requirement intends to support equality of experience, as codified in the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, said Fletcher. Thus, whatever information is written or spoken should be as clear and understandable to people with disabilities as it is for people who do not have disabilities, Fletcher observed. But what this principle means for hearing is still in many cases a mystery.

Drivers of Inclusive Design

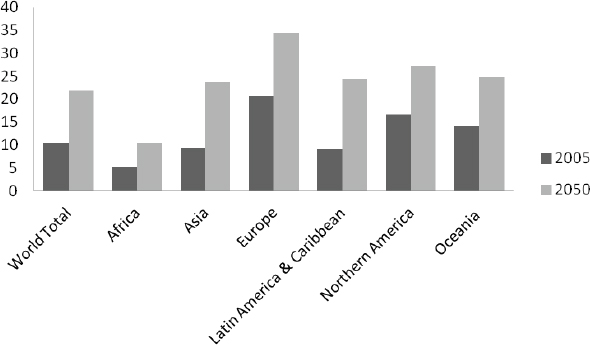

Global aging is the number one catalyst for inclusive design, said Fletcher (see Figure 6-1). According to Fletcher, every day 10,000 baby boomers turn 64 in the United States, and this will keep happening until 2031. “That anyone can ignore that is astonishing to me, and yet we do.” Americans have what the social historian Barbara Defoe Whitehead called

FIGURE 6-1 Percentage of population age 60 and older, 2005 and 2050.

SOURCE: Data from United Nations, 2010.

“an aging society and an adolescent culture,” said Fletcher: “I sometimes feel hopeful that we are moving from that, but not very hopeful.”

The second catalyst for inclusive design is disability. One in seven people on the planet has a disability, 80 percent of them in the developing world, said Fletcher. In the United States, the most common reasons for functional limitations are arthritis, back problems, heart disease, and respiratory disease. More than 55 million adults in the United States have a disability, including half of people older than age 65. Furthermore, these statistics do not count sensory or cognitive losses. “Nonapparent conditions are the norm,” according to Fletcher.

Reframing the Role of Design

Inclusive design is a framework for the design of places, things, information, communication, and policy that focuses on the widest range of people operating in the widest range of situations without special or separate design provisions. As Fletcher said, the idea is human-centered design of everything with everyone in mind. According to a set of principles developed by a group of U.S. organizations in 1997, universal design calls for the following:

- Equitable use

- Flexibility in use

- Simple, intuitive use

- Perceptible information

- Tolerance for error

- Low physical effort

- Size and space for approach and use

On an international level, Fletcher said, the World Health Organization has recommended universal design as the most promising framework for identifying the facilitators that would minimize disability and support independence and full community integration. Similarly, the Madrid International Plan of Action on Aging calls for ensuring enabling and supporting environments. And the United Nations Convention on the Human Rights of People with Disabilities calls for respect, nondiscrimination, participation, inclusive design, equality, and accessibility. “We are talking about an aspiration for thriving in a world in which we cannot afford, given the volume of functional limitation, anything less,” said Fletcher.

Fletcher cited several examples where inclusive design can significantly improve lives. One is to reduce the confusion felt by people taking medicines by designing better packaging and clear labeling of the medicines. “My father, who takes 11 drugs every day, does not have this,” said Fletcher. “He is legally blind and struggles with 11 tubes with white caps, none of which he can read.” Another example involved the redesign of a hospital in Singapore to be more patient centered. For example, in every room, at every shift, the names and photos of staff on shift are posted on the walls so that patients know who is taking care of them. Fletcher also mentioned a tablet that the Duke Cancer Center uses to screen the symptoms of patients. While in the waiting rooms, patients fill out a survey of 88 questions, rating their symptoms on a scale of 1 to 10. In this way, patients can report private matters to oncologists quickly and efficiently.

Finally, a focus on acoustics in building design, which is often neglected in design and construction because of cost considerations, can help make communication universal. For example, meeting rooms and conference tables can be engineered to help others see people speaking, recognizing the importance of visual connection to speech.

Different countries approach these issues differently, Fletcher noted. Cabs, subway stations, and museums are looped in London. The Kabukiza Kabuki Theater in Japan provides tablets with a guide for context and a script for narrative. A fire alarm company in Tokyo has even created a scented fire alarm, with tests on sleeping people showing that almost all the hearing-impaired people exposed to the odor of wasabi woke up within 2-and-a-half minutes of exposure. “You don’t have to worry about whether your telecoil is turned on.”

Design for people with disabilities and mainstream design can inspire,

provoke, and radically change each other, Fletcher said. Hearing aids that look like jewelry and inexpensive solar-powered hearing aids are just two examples.

Inclusive design still faces an enormous research agenda, Fletcher concluded. It is an idea related to values more than evidence. But attitudes are changing, at least in some countries, she said. The Japanese, for example, are conducting research and development from the first conceptual design conversations. “They feel that they have a stake in figuring out how to maximize independence for as long as possible. They feel that they have an obligation, as a culture in an aging society, to make a difference.”

During the discussion period, a workshop participant made the important point that technologies for some people with hearing loss need to be very simple. For example, older people can be very intimidated by cell phones, she said. “We have pictures of my mother’s cell phone and her remote control for her TV set. This may sound surprising to you, but my mother very often mixes up the remote control for the TV set with her cell phone. This is the level we have to be thinking about. We need to be thinking about hearing devices that the older aging population can put on and use. If they can’t operate it, they are not going to use it.” Even with cochlear implants, people may not have the manual dexterity to operate the controls. “We are talking not about 60-year-olds who are used to using computers. We are talking about older people who very often don’t have that,” said this participant.