3

Assessment as an Agent for Change

Key Messages

- Assessment of organizational culture could be a way to make explicit and bring to the surface many of the issues around the hidden curriculum. (Tassone)

- Although cost effective, one negative aspect to an outcomes assessment is the loss of valuable data by aggregating individuals’ roles on the team. (Zodpey)

- Involve the health professional students from the beginning by perhaps sending them to the communities to try and understand what the needs are. This strengthens the link between education and health systems and potentially creates a new generation of socially accountable practitioners. (Palsdottir)

- Asking patients about their experiences in an encounter with health providers from an interprofessional practice perspective could also be a strong motivator for faculty to improve their communication and collaborative skills. (Sewankambo)

- Negative role models run the risk of destroying leadership capacity in students. (De Maeseneer)

In keeping with a goal of the Forum—to demonstrate innovative techniques of learning with and from health professional educators from around the globe and within the Forum membership—members of the Forum

engaged in a World Café. This structure allowed for a series of quick-moving facilitated table discussions related to challenges with assessment of health professional education. The host of the café was Forum member Sarita Verma, who co-leads the Forum’s Canadian Interprofessional Health Leadership Collaborative (CIHLC). She began by stating the objective of the session and the role of the participants.

The objective of the World Café was to stimulate discussion and critical thinking about a dilemma faced by partners from around the world who are struggling to assess various aspects of interprofessional education (IPE) and interprofessional practice (IPP). This was accomplished with the help of seven facilitators who each developed a question (see Box 3-1). That question was presented seven times to seven different sets of Forum members, who moved from table to table hearing a 1-minute presentation by the facilitator, followed by 4 minutes of discussion about how the challenge might be overcome. In the end, each facilitator presented his or her individual assessment of the problem and potential solutions.

To orient the members to the questions, Verma referred to the Lancet Commission report Health Professionals for a New Century (Frenk et al., 2010). In it, the commissioners described a key weakness of most health systems that results in disjointed patient care stemming from episodic encounters with multiple providers who offer little continuity of care. The opportunities for those providers to actually interrelate with each other, said Verma, is one of the biggest challenges faced by health professionals today. This has major implications for health professional education and interprofessional care as described by Frenk et al. (2010) in their Lancet Commission report problem statement. An excerpt from the statement is noted below and set the foundation for the discussions at the World Café.

Health Professionals for a New Century: Problem Statement

Professional education has not kept pace with these challenges, largely because of fragmented, outdated, and static curricula that produce ill-equipped graduates. The problems are systemic: mismatch of competencies to patient and population needs; poor teamwork; persistent gender stratification of professional status; narrow technical focus without broader contextual understanding; episodic encounters rather than continuous care; predominant hospital orientation at the expense of primary care; quantitative and qualitative imbalances in the professional labor market; and weak leadership to improve health-system performance. Laudable efforts to address these deficiencies have mostly floundered, partly because of the so-called tribalism of the professions—the tendency of the various professions to act in isolation from or even in competition with each other.

SOURCE: Frenk et al., 2010, p. 1.

This chapter provides a summary of the discussions that took place at each table during the World Café.

TABLE 1 QUESTION:

What challenges do we face when trying to assess

interprofessional collaboration in people in leadership

roles, and how can these challenges be addressed?

Table 1 Leader: Lesley Bainbridge, CIHLC

Lesley Bainbridge from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, facilitated the table discussion that looked at assessment of a collaborative leader, the challenges to that, and the potential solutions.

One challenge, she said, is a lack of recognition of collaborative leadership as a legitimate form of leadership. A way to overcome this could be to develop matrix models of organizational structures that embrace interconnectedness and multiple leaders within the overall structure in order to gain greater understanding of the value of collaborative leadership.

Another obstacle is that groups may not be ready for collaborative leadership and therefore are not able to assess a collaborative leader. A solution might be to better prepare groups and learners for collaborative leadership by clearly defining collaborative leadership and building a framework that might highlight core competencies for effective collaborations. Without such a framework or definition, it would be impossible to develop metrics for assessing a collaborative leader, said Bainbridge.

The ideal solution would be to develop both the framework and the definition collaboratively so it is widely accepted, thus making it easier to compare results from various sources. However, she said, if all the personal views of what constitutes a leader are in forming the definition, this adds a layer of complexity because each person might have a different perspective on what constitutes a strong, collaborative leader. Also, it is difficult to measure outcomes of a collaborative leader in a system that values outcomes other than those achieved by a collaborative leader. Because multiple collaborative leaders could be part of one team, there is an additional challenge of how to differentiate the collaborative leaders from the team leader. Bainbridge said that clarification of roles and approaches to leading would help differentiate these types of leaders.

It would be most helpful if collaborative leadership were part of the curriculum of health professional education so the concepts would be well understood by students when they enter fully into a practice environment. Bainbridge added that making a convincing case for collaborative leadership would be key to incorporating the concept into education and practice. But to make a convincing case, one would have to link best practices (as-

BOX 3-1

World Café Discussion Topics and Questions

Table 1 Leader: Lesley Bainbridge, CIHLC

Context: Traditional leadership skills and abilities may not explicitly embrace those needed for collaborative leadership within and among organizations. The CIHLC’s current definition of collaborative leadership is:

Collaborative leadership is a way of being, reflected in attitudes, behaviors, and actions, that are enabled by individuals, teams, and/or organizations, and integrated within and across complex adaptive systems to transform health with people and communities, locally and globally.

Question: What challenges do we face when trying to assess interprofessional collaboration in people in leadership roles, and how can these challenges be addressed?

Table 2 Leader: Maria Tassone, CIHLC

Context: Assessment in health professions education often focuses at the individual student, clinician, leader, or team level. What is also needed is a supportive organizational culture in which individuals and teams are enabled to practice and lead collaboratively.

Question: How might we approach assessment of collaboration and collaborative leadership within and across organizations?

Table 3 Leader: Sanjay Zodpey, Indian Country Collaborative

Context: A team usually delivers public health services to beneficiaries as part of public health practice. Within developing countries, such teams face constraints at the workplace while delivering public health services.

Question: How can we assess individual versus team performance at the workplace?

Table 4 Leader: Juanita Bezuidenhout, South African Country Collaborative Context: IPE is viewed as an additional “activity” in an already overfull curriculum, and some even regard it as yet another discipline silo.

Question: How can we use faculty development in assessment as a covert and overt change management opportunity to promote acceptance of interprofessional practice among clinical faculty?

Table 5 Leader: Nelson Sewankambo, Ugandan Country Collaborative Context: Faculty require motivation for them to embrace IPP which, if done successfully, will provide students with role models for practicing IPE.

We work hard in creating a collegial environment where students from different professions learn from and with each other. But despite our best efforts, when students enter the clinical environment they lack appropriate role models demonstrating good interprofessional practice in the way we outlined it.

Question: Based on your experience, are there any incentives within assessment and evaluation that could motivate clinical faculty to embrace interprofessional practice?

Table 6 Leaders: Bjorg Palsdottir, THEnet, Belgium, and Jehu Iputo, THEnet, South Africa

Context: Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) is a consortium of 11 health professions schools committed to transforming health professions education to improve health equity. THEnet developed an institutional evaluation framework that links education to health system outcomes through the concept of social accountability. THEnet is working with the World Health Organization (WHO) and others to ensure that the framework is relevant and useful for all health professions groups.

Question: How might better linkages between education and practice be assessed?

Table 7 Leader: Jan De Maeseneer, Ghent University, Belgium

Context: Transformational leadership occurs when leaders articulate the purpose and the mission interactively with their group by intellectually stimulating the group, championing innovation, and inspiring group members to become change agents. Transformational leaders are characterized by

- Connecting one’s identity to the group identity,

- Being a role model,

- Challenging group members to take greater ownership in the change process,

- Creating trust,

- Empowering group members, and

- Creating a safe environment to make change happen.

Question: Based on this definition, how do you assess transformational leadership in students?

sessed over time) to outcomes in order to fully determine the value of the collaborative leader.

TABLE 2 QUESTION:

How might we approach assessment of collaboration and collaborative leadership within and across organizations?

Table 2 Leader: Maria Tassone, CIHLC

Maria Tassone from the University of Toronto and co-lead of the Canadian Collaborative also focused on collaborative leadership, but from an institutional level. She addressed how to approach assessment of collaboration and collaborative leadership within and across organizations.

Her report echoed Bainbridge’s with an expression of need for an operational definition of collaboration and collaborative leadership as well as core competencies in this area that could be used in assessments. But, said Tassone, without a sincere commitment and role modeling by senior leaders, the likelihood of success would be low. A suggestion might be to ask employees within an organization to assess their senior leaders based on their sincerity to commit to role modeling collaborative behaviors. This would be a start, but success would also entail establishing strategic goals within and across organizations that could then be used for assessing areas of success. Such analyses would likely need to balance between process and outcomes assessments.

Much of what Tassone described had to do with an organizational culture and how to assess it in order to propose changes. For example, assessment of organizational culture could be a way to make explicit and bring to the surface many of the issues around the hidden curriculum. To do this, it would be critical to bring in people from outside of the organization and outside of the “regular voices” to gain greater insight into the organization’s culture, she said. However, external perspectives would be just part of the assessment because self-reflection within organizations and across institutions are also important. The IP-COMPASS1 is one tool from the University of Toronto intended to improve interprofessional collaboration and interprofessional educational experiences by looking at how the organizational culture influences interprofessionalism in clinical settings. Another tool—network analysis—could provide a better understanding of relationships among the senior team members and others within their organization. And finally, mapping exercises can provide valuable information like frequency of communications, how power is shared, where decisions

___________________

1See http://www.wrha.mb.ca/professionals/collaborativecare/files/S2-IP-COMPASS.pdf for more information (accessed April 18, 2014).

are made, and how information is shared from a transparency perspective. This would be helpful in assessing collaborative leadership from an institutional level.

TABLE 3 QUESTION:

How can we assess individual versus team performance at the workplace?

Table 3 Leader: Sanjay Zodpey, Indian Country Collaborative

The question Forum member Sanjay Zodpey addressed looked at conducting assessments in a low-resource environment. To begin, he stated that the assessment would be conducted in a public health setting, most likely at the managerial level by the person most responsible for the team. In addition to financial constraints, there would be human resource constraints. These constraints would need to be understood within the context of the community and the country where the assessment would take place. This would likely influence the decision to assess individuals versus the collective team.

For an individual assessment, the specific roles and tasks each team member is responsible for would have to be clearly stated. In this way, team versus individual responsibilities could be delineated. A potential tool is the 360-degree assessment of teams and their outputs. Zodpey was conflicted as to whether this would be too difficult to undertake in resource-limited settings. There is the challenge of getting candid responses, and the time it takes to get the responses could be overly burdensome on the limited staff. Despite these limitations, Zodpey stated that if the questions and the processes were kept very simple, this could be a useful assessment tool.

In the context of the team, providing small incentives to all those who participate in the assessment could boost response rates, particularly when involving the community in the process. It could also be useful to engage other nearby groups that are performing similar services in order to share the assessment tools, the process designs, and the interpretation of the results. Similarly, it may be possible to engage local education institutions to create and validate tools; however, given the limited resources, it would be desirable to maximize their use by creating flexible and adaptable tools so they could be used in a variety of settings.

Another idea is to organize the assessment around a specific subpopulation to pilot test the assessment before committing the limited resources to conducting a full assessment. Understanding what can and cannot be changed in the system before starting the full assessment would save time and money as well as provide insight into the team culture.

Assessing clinical outcomes could be a valuable, inexpensive measure in determining whether the team accomplished its goal, particularly if it is

linked to the strategic plan. Although cost effective, one negative aspect to an outcomes assessment is the loss of valuable data by aggregating individuals’ roles on the team. Zodpey stated that such a tool is useful but should not be used exclusively. When using this and other team-related assessment tools, how the team is defined can influence the assessment process. For example, the mix of skilled and unskilled providers and workers would alter the process by which the assessment is conducted.

One final thought Zodpey expressed involved understanding not just the supply side, but the demand side as well. Assessing health workers (supply) is useful, but gathering data from industry (demand) about what it values could offer information as well as potential resources for more in-depth assessments.

TABLE 4 QUESTION:

How can we use faculty development in assessment as a covert and overt change management opportunity to promote acceptance of interprofessional practice among clinical faculty?

Table 4 Leader: Juanita Bezuidenhout, South African Country Collaborative

Juanita Bezuidenhout reported on how faculty development in assessment might be used to embed IPE into curricula so IPE is not separated as its own silo. The importance of top management’s involvement is key in this regard, said Bezuidenhout. Providing rewards and recognition for measurements in IPE pushes faculty to learn about IPE assessment and engaging in IPE in order to assess it. As Bezuidenhout stated, “We must measure what we value and value what we measure.” In this way, senior management reinforces the importance of IPE. Through faculty development on IPE assessment, champions can be identified who can further promote the IPE agenda.

In her remarks, Bezuidenhout speculated that faculty development workshops on assessment could emphasize IPE, making it an explicit purpose of the meeting. Stacking the room with interprofessional attendees and interprofessional facilitators could build momentum for more IPE opportunities. With such all-around support, the mutual excitement would propel a desire for a longer-term focus on IPE—possibly through a spiral curriculum. In this way, IPE would be introduced and repeated at later faculty development workshops to build on the previously gained knowledge and understanding of IPE set in previous workshops.

Another source of momentum for IPE could be students from various professions demanding IPE, or patients who are invited to the assessment workshops. This might add a component of reality and value to the faculty’s discussions around better communication through team-based care

and IPE. Also, during faculty development workshops, examples of IPE assessments of individuals and teams could be presented along with their relevance to specific situations so faculty are exposed to new ways of thinking and problem solving.

Bezuidenhout also encouraged the use of existing tools for pilot studies that could validate their use and make it easier for others to engage in shared assessments. The workload of all faculty is lightened, and the collective data can be used to demonstrate to senior management the value of IPE. This led to Bezuidenhout’s final comment on promoting research around IPE-based assessment by persuading more interprofessional teams to publish research that could not only add to the knowledge base of interprofessional work but also increase the visibility and the acknowledgment of the value of educating students interprofessionally.

TABLE 5 QUESTION:

Based on your experience, are there any incentives within assessment and evaluation that could motivate clinical faculty to embrace interprofessional practice?

Table 5 Leader: Nelson Sewankambo, Ugandan Country Collaborative

For his report, Forum member Nelson Sewankambo addressed how to develop good role models in IPP to serve as a positive learning environment for students engaging in IPE. Challenged with how to incentivize staff to embrace IPP and IPE, his theory was to use assessment as a driver for incentivizing faculty to do a better job.

Sewankambo considered the engagement of students to participate in the assessment, to contribute suggestions on the assessments, and to participate in the assessment of IPP and IPE; he said that the students’ feedback to practitioners and educators could be a very powerful motivator for staff to do a better job. Asking patients about their experiences in an encounter with health providers from an IPP perspective could also be a strong motivator for faculty to improve their communication and collaborative skills.

Another suggestion was to publically recognize and reward good performance in both IPP and IPE so others could learn from positive examples. Ideally, these exemplars would be assessed for their ability to demonstrate the link between clinical outcomes and the interprofessional educational process leading to success. However, Sewankambo recognized that achieving this has been difficult to demonstrate in the past. Regardless, practitioners want to do a good job in improving patient outcomes, he said. Through the assessment process, it becomes clear as to whether teams are achieving positive patient outcomes or not. The assessment can be used to

point out where the teams could have performed better, which would be a motivator for staff to improve the elements that make up strong IPPs.

In his presentation, Sewankambo expressed the value in linking the academic assessment to the clinical assessment so the two are mutually reinforcing in a way that incentivizes faculty to do more and to do better. Impacts on outcomes that are uncovered through the assessment process would be communicated clearly to practitioners in order for them to strive for greater excellence in team-based care. Through this, more role models will begin to form for students to emulate.

He also acknowledged that assessments of teams require assessments of individuals within those teams. It is through the assessment process that one can explore in greater depth why one team succeeds in improving patient outcomes while another team in the same environment does not. Getting at the differences between the teams may require an individual-level assessment to better understand why these teams are functioning differently.

Like Tassone, Sewankambo believed that assessment is a way of exposing the hidden curriculum. The hidden curriculum is important in driving education, but it is rarely assessed. Linking the assessment of learners and their expectations to those of faculty may be one way of assessing the hidden curriculum. He suggested that the same rigor used to assess students could be used in developing assessment tools of faculty within IPE and IPP. In this way, an organizational culture around IPE and IPP could be applied that would expand the number of interprofessional role models and perpetuate a cycle of IPE and IPP.

TABLE 6 QUESTION:

How might better linkages between education and practice be assessed?

Table 6 Leaders: Bjorg Palsdottir, THEnet, Belgium, and Jehu Iputo, THEnet, South Africa

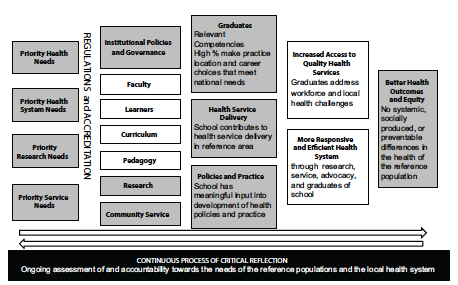

Bjorg Palsdottir, representing the Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) on the Forum, began her report by describing THEnet. It is a partnership of schools that address health workforce needs and health needs in disadvantaged communities in order to promote socially accountable health-workforce education. When THEnet members came together recently, they developed a framework to measure how well health professional schools are meeting community needs and are moving toward greater social accountability (see Figure 3-1). This framework provided the backdrop for the question Palsdottir posed about linkages between educating health professionals to be socially accountable care providers, how that education affects their work as practitioners, and how that effect could be measured.

FIGURE 3-1 Institutional Evaluation Framework for Social Accountability.

SOURCE: Adapted from Palsdottir, 2013.

Discussions at Palsdottir’s table involved selecting appropriate indicators (1) for measuring whether schools are addressing and meeting the needs of communities within their respective health systems; and (2) for measuring improved linkages between education and service delivery. This can only be accomplished through strong leadership, she said. And collaborative leadership—as highlighted by the first two presenters—is essential for this change to happen particularly at the top levels of education and health systems.

To begin developing a measurement tool linking education and service delivery, one might start by looking at the community needs together with community members and patients, who are the end users of the educational and health systems. Then, one might use patient and community outcomes as the measurement indicator of success. Mapping out who is being served by the health system would be critical information and a useful exercise for all the schools that are involved in the analysis to perform. Another idea is to involve the health professional students from the beginning by perhaps sending them to the communities to try and understand what the needs are. This strengthens the link between education and health systems, and it potentially creates a new generation of socially accountable practitioners.

The ultimate goal of the analysis is to measure educational impacts on patient and community outcomes. But, said Palsdottir, there is important information that could be lost if just a summative analysis is performed.

For example, it would be very beneficial to capture whether a curriculum reflects socially accountable values and if so, whether financial support is provided for such efforts such as training and community engagement. Without funding, the project may look good on paper but be unable to accomplish any of its intended impact.

Tracking graduates was an important element Palsdottir identified for analyzing the effect of education on career choices that value social accountability and community service. To do this, she said, one might follow the zip codes of their graduates. This would provide insight into whether graduates are working in a rural state. More in-depth surveys could follow up on the type of work the graduate is performing that might include working with disadvantaged populations in urban settings. An even more detailed data collection could possibly assess whether graduates are performing work that is reflective of the needs of the communities they serve.

Palsdottir also suggested that other sectors might help inform the analysis. For example, insurance and pharmaceutical companies—who employ the graduates of the health training programs—could be asked about the kind of competencies they require for employment. The same question could also be posed to communities. In this way, it may be possible to determine whether the intended, socially accountable education of health professionals is actually improving the communities they serve.

TABLE 7 QUESTION:

Based on the presented definition of transformational leadership, how do you assess transformational leadership in students?

Table 7 Leader: Jan De Maeseneer, Ghent University, Belgium

In laying the foundation for his report, Forum member Jan De Maeseneer drew on a section of the Lancet Commission report about transformative learning for developing leadership attributes and enlightened change agents (Frenk et al., 2010). Transformative leadership is required for such learning to be incorporated into education, said De Maeseneer, but some may eschew the responsibility if they do not see themselves as leaders. In this regard, it may be more useful to refer to “change agents” rather than transformative leaders. Providing learning opportunities for creating change agents to all, rather than a select few, could perpetuate this thinking that everyone can be an agent of change.

The assessment of transformational leadership in learners will depend on the context where the behaviors would be assessed. For example, there is leadership to gain an individual patient’s commitment to change, leadership on interprofessional teams, leadership in communities, and leadership in making policy. Students can be trained at all of these different levels,

although the assessments at each level would differ. What would remain intact regardless of the context or the level is the social mission and the community orientation. Leadership is not only about inward looking, but also about outward looking to the needs of society, said De Maeseneer.

De Maeseneer said that the definition of transformative leadership is important for assessing transformational leadership. It contains certain qualities, including

- Connecting one’s identity to the group’s identity,

- Being a role model,

- Challenging group members to take greater ownership,

- Pushing for needed process changes,

- Creating trust,

- Empowering group members,

- Establishing safe environments,

- Intellectually stimulating the group,

- Championing innovation, and

- Inspiring group members to become change agents.

Translating these qualities into behaviors would enable an assessment of the learner. This could include both process and outcome measures. Peer assessment was identified by De Maeseneer as an essential feature of both because of the importance of colleagues and peers in identifying and supporting leaders.

Whether leaders are born or produced remains a question for greater debate. And the question still stands, whether institutions have the responsibility to select students based on certain leadership qualities or whether they should be responsible for creating opportunities for transformational leadership skills development. Like Tassone and Sewankambo, De Maeseneer brought up the hidden curriculum, saying that negative role models run the risk of destroying leadership capacity in students. Instead, he embraces curricula that share power and institutional governance with students to prepare them for leadership roles. One example is student-led primary health care services, where students learn to take responsibility to be transformational leaders.

Much of the learning about transformational leadership would be through experiences rather than didactic education, meaning that the assessment would not always be explicit. It would be adaptable, at times implicit, and would contain quantitative as well as qualitative elements. The qualitative piece would no doubt involve a reflective component.

Of significant importance to transformative leadership, said De Maeseneer, are the role models. This raised questions for him over the faculty selection criteria. Often, faculty are hired because of their in-depth knowledge of a

particular subject and not because of their transformational leadership capacity. Such qualities might include strategic thinking, a willingness to take risks, and a visionary outlook. But most importantly, transformative leaders possess a commitment to the social mission. In the end, said De Maeseneer, transformational leadership is about making a difference where it really matters.

REFERENCES

Frenk, J., L. Chen, Z. A. Bhutta, J. Cohen, N. Crisp, T. Evans, H. Fineberg, P. Garcia, Y. Ke, P. Kelley, B. Kistnasamy, A. Meleis, D. Naylor, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Reddy, S. Scrimshaw, J. Sepulveda, D. Serwadda, and H. Zurayk. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923-1958.

Palsdottir, B. 2013. Institutional evaluation framework for social accountability. Presented at the IOM workshop Assessing health professional education. Washington, DC, October 10.