Policies and Payment Systems to Support High-Quality End-of-Life Care

Financial incentives built into the programs that most often serve people with advanced serious illnesses—Medicare and Medicaid—encourage providers to render more services and more intensive services than are necessary or beneficial, and the lack of coordination among programs leads to fragmented care, with all its negative consequences. In short, the current health care system increases risks to patients and creates avoidable burdens on them and their families. Meanwhile, the practical but essential day-to-day support services, such as caregiver training, nutrition services, and medication management, that would allow people near the end of life to live in safety and comfort at home—where most prefer to be—are not easily arranged or paid for.

The U.S. health care system is in a state of rapid change. The impact of these shifting programs and incentives—and both their beneficial and unintended negative consequences—on Americans nearing the end of life should not be overlooked. Appropriate measurement and accountability structures are needed to ensure that people nearing the end of life will benefit under changing program policies. In assessing how the U.S. health care system affects Americans near the end of life, the committee focused on evidence that the current system is characterized by fragmentation and inefficiency, inadequate treatment of pain and other distressing symptoms, frequent transitions among care settings, and enormous and growing care responsibilities for families.

While the committee focused on improving the quality of care for people with serious advanced illnesses who may be approaching death, it also was attentive to the need to control spending throughout the U.S.

health care system. Likewise, most new health program proposals for the last several decades, up to and including the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), have tried to balance increasing access and improving the quality of care with managing costs. Indeed, decades of experience with the nation’s flagship health care programs—Medicaid for low-income Americans (including those who “spend down” their life savings to become eligible) and Medicare for those aged 65 and older and persons with disabilities—suggest that improving the quality of care can reduce costs.

For those nearing the end of life, better quality of care through a range of new delivery models has repeatedly been shown to reduce the need for frequent 911 calls, emergency department visits, and unnecessary urgent hospitalizations. Evidence suggests that palliative care, hospice, and various care models that integrate health care and social services may provide high-quality end-of-life care that can reduce the use of expensive hospital- and institution-based services, and have the potential to help stabilize and even reduce health care costs for people near the end of life. The resulting savings could be used to fund highly targeted and carefully tailored social services for both children and adults (Komisar and Feder, 2011; Unroe and Meier, 2013), improving patient care while protecting and supporting families. This chapter describes those opportunities.

The U.S. health care system is a complex mix of individual professionals, acute and long-term care facilities, dozens of ancillary services, payers, vendors, and many other components. Making a potentially cost-saving change in one area, regardless of how theoretically sound it may be, may create a response elsewhere in the system that prevents overall savings from being achieved. For that reason, piecemeal reforms will not work, and comprehensive approaches are needed.

The committee notes that many positive aspects of the nation’s current evolving health care system—the opportunities it affords for patients to choose providers and treatments, the growing number of quality initiatives, its investment in research and technology, and the commitment of large numbers of professionals and institutions to care for the frailest and sickest Americans—could be lost in draconian or ill-considered cost-containment measures, such as stinting on needed and beneficial care. For that reason, the committee focused on the system changes that would not only serve the needs of the sickest patients and their families but also, as a result of better quality, lead to more efficient, affordable, and sustainable practices. To this end, much can be learned from existing successful programs and care delivery models that could be applied more widely.

In May 2013 testimony before the House Committee on Ways and

Means Subcommittee on Health, Alice Rivlin1 began with an interesting question and arrived at an even more interesting answer:

Why reform Medicare? The main reason for reforming Medicare is not that the program is the principal driver of future federal spending increases, although it is. The main reason is not that Medicare beneficiaries could be receiving much better coordinated and more effective care, although they could. The most important reason is that Medicare is big enough to move the whole American health delivery system away from fee-for-service reimbursement, which rewards volume of services, toward new delivery structures, which reward quality and value. Medicare can lead a revolution in health care delivery that will give all Americans better health care at sustainable cost. (Rivlin, 2013)

Rivlin’s remarks highlight the two issues facing Medicare and the U.S. health sector as a whole—costs and quality. These two intertwined issues pervaded this study.

The poorer quality of care and higher costs that result from lack of service coordination, risky and repeated transitions across settings and programs, and fragmented and siloed delivery and payment systems affect large numbers of Americans, including those nearing the end of life. Although it is too early to predict the ultimate effects of the ACA, it is not too soon to start calling for accountability and transparency in care near the end of life to ensure that the goals of health care reform are realized for the most vulnerable and sickest beneficiaries.

This chapter describes systemic shortcomings in U.S. health care that hinder high-quality, compassionate, and cost-effective care for people of all ages near the end of life and their families. The chapter begins by summarizing the quality and cost challenges that must be faced in efforts to redesign policies and payment systems to support high-quality end-of-life care. It then provides background information on the most important programs responsible for financing and organizing U.S. health care and the perverse incentives in those programs that affect people near the end of life. Next, the chapter examines the gap between the services these programs pay for and what patients nearing the end of life and their families want and need. The chapter then turns to opportunities and initiatives to address the shortfalls and gaps in the current system and the concomitant need to establish greater transparency and accountability in the delivery of care near the end of life. After outlining research needs, the chapter ends with the commit-

_______________

1Alice Rivlin is Leonard D. Schaeffer chair in health economics at the Brookings Institution, a visiting professor at the Public Policy Institute of Georgetown University, and director of Brookings’ Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform. She recently served as a member of the President’s Debt Commission, was founding director of the Congressional Budget Office, served as Office of Management and Budget director, and was Federal Reserve vice-chair.

tee’s findings, conclusions, and recommendations on policies and payment systems to support high-quality end-of-life care.

Americans of any age who have a serious and potentially life-limiting medical condition—from infants with a devastating genetic disorder, to young adults brain-injured in an automobile crash, to frail older people with multiple chronic diseases—can experience a system that is structured and financed to provide costly interventions, high-tech services, and crisis and emergency care. This system is experienced by many thousands of people. What requires close examination and reform is how those resources are spent and whether they are well matched to the values, goals, wishes, and needs of patients and families. Current evidence suggests they are not.

The health care payment system in the United States is different from that in other wealthy, industrialized nations and has resulted from the nation’s unique politics and history. The U.S. system rewards the volume of medical procedures and therapies provided, and typically neither recognizes nor pays for the day-to-day, long-term services and supports—such as a companion to help with dressing, bathing, and eating—that are needed by people with advanced serious illnesses and their families (Feder et al., 2000; MedPAC, 2011; Rivlin, 2013). As noted in Chapter 2, given an informed choice, most people would prefer to have these ongoing needs met in their homes and communities. Because they often cannot, they routinely and repeatedly resort to 911 calls, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations that are neither beneficial nor wanted (Meier, 2011). This is poor-quality care, and it is extremely expensive.

People with advanced serious illnesses and multiple chronic conditions share certain needs independent of their diagnosis, stage of illness, or age. They have a high prevalence of pain and other distressing symptoms that adversely affect function and quality of life. They are at high risk of functional dependency, and the majority, like more than 60 percent of the costliest 5 percent of Medicare beneficiaries, require help from another person in meeting basic needs on a daily basis. Many suffer from cognitive impairments, such as dementia or delirium, and from other mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety—problems that require specialized attention and intervention. Meeting such needs places enormous burdens—physical, emotional, practical, and financial—on their families and especially, as discussed in Chapter 2, on family caregivers.

In this context, the committee believes a major reorientation of Medicare and Medicaid is needed to craft a system of care that is properly designed to address the central needs of nearly all Americans nearing the end

of life. This reorientation will require recognizing the root causes of high utilization of the system (such as exhausted family caregivers); designing services to address those causes (such as round-the-clock access to advice by telephone); reallocating funding away from preventable or unwanted acute/specialist/emergency care to support more appropriate services; and reducing the financial incentives that drive reliance on the riskiest, least suitable, and most costly care settings—the emergency department, the hospital, and the intensive care unit. Fundamentally, services must be tailored to the evolving needs of seriously ill individuals and families so as to provide a positive alternative to costly acute care and to help these patients remain safely at home, if that is their preference. Such tailoring of services would benefit far more people than attempting to reduce services for those in predictably imminent danger of dying.

Forty years ago, U.S. national health care expenditures totaled $75 billion, or 7.2 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP); by 1990, they totaled 10 times that amount—$724 billion—or 12.5 percent of GDP; and just 22 years later, in 2012, they totaled $2.8 trillion, or about 17.2 percent of GDP, having risen some $100 billion between 2011 and 2012 (Martin et al., 2014).2

With by far the largest budget of any department in the federal government and a program scope that “touches the lives of virtually every American” (IOM, 2009, pp. 21-23), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) exerts enormous influence over health care in America. That influence is exerted chiefly through Medicare and Medicaid, and the cost challenges in the Medicare and Medicaid programs are of urgent and longstanding concern to policy analysts across the political spectrum (Altman and Shactman, 2011, p. 345; Moffit and Senger, 2013; Robillard, 2013).

The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform called federal health spending the nation’s “single largest fiscal challenge over the long run” (National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, 2010, p. 36). Medicare and Medicaid have grown exponentially since their establishment almost 50 years ago, and their rules and structure have done much to shape care for the seriously ill and those who are dying. Financial pressure on federal health spending has several causes:

_______________

2The $2.79 trillion figure includes expenditures for personal health care ($2.36 trillion), government administration ($33 billion), net cost of health insurance ($164 billion), and government public health activities ($75 billion), as well as $160 billion in noncommercial research, structures, and equipment.

- Medicare and Medicaid are expensive. The two programs cost a combined $994 billion in 2012,3 or about 36 percent of total U.S. national health expenditures, and are projected to cost $1.125 trillion in 2014 (Cuckler et al., 2013). By consuming a large and growing portion of public spending, Medicare and Medicaid may crowd out needed investments in education, the environment, housing, infrastructure such as roads and bridges, alleviation of poverty, and other areas, which together arguably have a greater effect than medical care on population health.

- Expenditures for the two programs continue to rise and are projected to account for an increasing share of the economy. Although overall growth in U.S. health expenditures has slowed in recent years, spending on Medicare grew by almost one-third between 2007 and 2012 (from $432.8 billion to $572.5 billion) and on Medicaid by about 30 percent (from $326.2 billion to $421.2 billion) (Martin et al., 2014). Medicare trustees project that the cost of the program will grow from 3.6 percent of the nation’s GDP in 2012 to 5.6 percent in 2035 (Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, 2013), while Medicaid expenditures are expected to more than double between 2013 and 2022, from $265 billion to $536 billion, especially with expansions in eligibility under the ACA (Elmendorf, 2013).

- The population is changing. The aging of baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) and the growing number of Americans who are living longer but with substantial burdens of chronic disease put pressure on both Medicare (health services) and Medicaid (long-term care). Older people are the population group most likely to have chronic conditions leading to functional dependency, and spending on patients of all ages with chronic conditions accounts for 84 percent of health care costs (Moses et al., 2013).4

- Family caregiving has its limits. Older Americans’ reliance on family members—whose care was valued at $450 billion in 2009—to serve as caregivers may be difficult to sustain (Feinberg et al., 2011). About one-half (45 percent) of American women aged 75 and older live alone, and their children, if they have any, may be unable to leave their own jobs to take on the caregiving role (AoA, 2013). A loss of family caregiving capacity would increase demand for services paid for by both Medicare and Medicaid.

_______________

3The sum of Medicare ($572.5 billion); Medicaid, federal ($237.9 billion); and Medicaid, state and local ($183.3 billion) (Martin et al., 2014).

4The Medicare-eligible population is 14 percent of the U.S. population and 40 percent of the population incurring high health care costs (see Appendix E).

- The proportional tax base for the programs is shrinking. The ratio of elderly Americans to working-age Americans, who pay the taxes that fund Medicare and Medicaid, is shifting. In 1990, there were 21 Americans aged 65 and older for every 100 working-age Americans (Bureau of the Census, 2013); the projection for 2030 is 38 Americans 65 and older for every 100 of working age. An ever-smaller proportion of working Americans will be asked to contribute to health care for people at all income levels, including those with large incomes and substantial financial assets.5

- The pay-as-you-go system has its limits. Despite popular misconceptions, Medicare is funded by current contributions and revenues. In general, beneficiaries have not fully “paid in” during their working years for the benefits they later “take out” (Jacobson, 2013). In 2010, for example, a one-income, average-wage couple took out more than $6.00 in Medicare benefits for every $1.00 paid in (Steuerle and Quakenbush, 2012).

Analysts differ in their views on the relative importance of the various factors implicated in the rise in federal expenditures on health care:

- One recent analysis suggests that most increases in health care costs since 2000 have not been the result of population factors, such as aging or demand for services, but of high prices (especially for hospital care), the cost of drugs and medical devices, and administrative costs (Moses et al., 2013). These authors conclude that higher prices accounted for some 91 percent of the increase between 2000 and 2011. Average prices for everything from pharmaceuticals to surgeries are dramatically higher in the United States than in other countries (Klein, 2013).

- Other analyses attribute growth in health care costs to a larger mix of factors. The Bipartisan Policy Center (2012), for example, cites 13 major contributors to costs,6 emphasizing that none of them exists in isolation and that policy interventions must address multiple cost drivers.

_______________

5Although higher-income beneficiaries pay somewhat more for their Part B (physician) coverage.

6The 13 cost contributors are fee-for-service reimbursement; fragmentation in care delivery; administrative burden; population aging, rising rates of chronic disease, and comorbidities; advances in medical technology; tax treatment of health insurance; insurance benefit design; lack of transparency about cost and quality to inform consumer choice; cultural biases that influence care utilization; changing trends in market consolidation; high unit prices of medical services; the legal and regulatory environment; and the structure and supply of the health professional workforce.

- Based on a series of workshops on lowering health care costs and improving outcomes, an Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee concluded that almost 31 percent of 2009’s total health care costs could have been avoided by eliminating unnecessary services, inefficiently delivered services, excess administrative costs, prices that were too high, missed prevention opportunities, and fraud (IOM, 2010a, Box S-2).

Because of these economic realities, recommendations simply to increase total Medicare or Medicaid expenditures—say, to add new benefits for people with advanced serious illnesses without reducing costs elsewhere—are unlikely to be accepted. Conversely, proposals that demonstrably reduce costs as a result of improving the quality of care may be far better received by policy makers of all political persuasions.

U.S. health spending has grown more slowly than expected since the recent recession, a trend that has persisted. The slowdown has been attributed to a number of factors, including less new technology, greater patient cost sharing, and increased efficiency of providers (Ryu et al., 2013). If the trend continues, public-sector health care spending through 2021 will be substantially lower than projected, some analysts believe, and “bring much-needed relief throughout the economy” (Cutler and Sahni, 2013, p. 848). Others are less optimistic and believe the fundamental structural, marketplace, pricing, and demographic causes of cost growth remain unchanged (Bipartisan Policy Center, 2012).

Despite the above analyses, people in their last year of life are widely believed to be a main driver of excess health care spending. As described in the background paper prepared for this study by Aldridge and Kelley (see Appendix E), however, people in the last year of life account for just under 13 percent of total annual U.S. health care spending.7 Although the top 5 percent of health care spenders account for 60 percent of all health care costs, almost 90 percent of that costliest 5 percent are not in their last year of life. Since 1978, expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries in the last year of life—many of whom have multiple chronic conditions and dementia—have held steady at just over one-quarter of all Medicare expenditures (see Appendix E). In light of this analysis, the oft-expressed concern about “excess spending in the last year of life” distracts from the real drivers of U.S. health care expenditures overall, such as those described above, or those

_______________

7This estimate is based on 2011 Health and Retirement Study data on cost of care in the last year of life paid by Medicare, adjusted to account for costs paid by other sources (Medicaid, 10 percent; out of pocket, 18 percent; other, including private payers, 11 percent). The per person estimate that resulted was then applied to all 2011 deaths to arrive at a total. A limitation of this approach is that it excludes information on the non-Medicare population; however, the majority of costs in the last year of life are covered by Medicare.

of the Medicare program in particular. Those drivers include the system incentives described in this chapter, which not only push people toward use of the expensive acute care system as a substitute for inadequate community and social services but also, by being so costly, inhibit expansion of those services.

FINANCING AND ORGANIZATION OF END-OF-LIFE CARE

The IOM reports Approaching Death (1997) and When Children Die (2003) acknowledge the importance of the U.S. health care system in securing the care needed by dying adults and children and the “complex and often confusing organizational, financial, and regulatory arrangements that link health care professionals and institutions with each other and with governments, insurers, and other organizations” (IOM, 2003, p. 181). The present report revisits many of these entrenched problems. (Appendix B provides an overview of progress on the two previous reports’ recommendations.)

Over the past five decades, Congress has established an array of programs intended to meet the health care needs of older and low-income Americans:

- Medicare, the largest program, covers Americans aged 65 and older, people with permanent disabilities receiving Social Security Disability Income, and those with one of several specific life-threatening conditions. As noted, Medicare is federally funded by current revenue.

- Medicaid covers pregnant women, children, adults with dependent children, people with disabilities, the low-income elderly, and in some states the “medically needy”8 (KFF, 2013a). Although people commonly think of Medicaid as a program for poor children and their parents, fully 30 percent of the program’s 2011 expenditures (approximately $125 billion) was for long-term care. Medicaid is financed jointly by the federal government and the states. The federal government allows the states wide administrative latitude, which results in great variability in benefits and eligibility among states.

- The nearly 10 million Americans who receive both Medicare and Medicaid benefits are termed “dual-eligible.” A recent study of 10 years of data on the extent and causes of people “spending down”

______________

8States that have “medically needy” programs allow people whose income exceeds usual Medicaid eligibility thresholds to enroll if their income minus medical expenses meets the eligibility standard (http://www.medicare.gov/your-medicare-costs/help-paying-costs/medicaid/medicaid.html [accessed December 16, 2014]).

- their assets to become eligible for Medicaid found that almost 10 percent of the non-Medicaid population aged 50 and older became Medicaid eligible by the end of the study. Almost two-thirds of Medicaid recipients became eligible by spending down, and people who spent down had substantially lower incomes and fewer assets to begin with—a finding “inconsistent with the common assumption that . . . people who spend down are predominantly middle class” (Wiener et al., 2013, p. ES-2).

The dual-eligible population faces special challenges because the separately created and managed health and social programs under Medicare and Medicaid are not coordinated and contain perverse eligibility and coverage incentives. These financial incentives create waste and result in patients moving back and forth between care settings (and payment options) not for medical reasons, but to maximize provider reimbursements. The result is care that is both poor quality and very costly. The ACA created a new Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office, described later in this chapter, in an attempt to address these challenges.

Table 5-1 briefly summarizes the principal programs available to meet the needs of people with serious advanced illnesses and their families. The paper by Huskamp and Stevenson in Appendix D provides additional detail, as does the series of “Payment Basics” papers available on the website of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC, an independent congressional agency, http://www.medpac.gov). The detailed regulations

TABLE 5-1 Major Health and Social Programs Available to People with Serious Advanced Illnesses

| Program | Number of Americans Who Benefit | Principal Services Covereda | Program Payments (FY 2012 unless noted) |

|

Traditional Medicareb (federal) |

|||

| Medicare Part A | 49.4 million (2012) | Primarily acute inpatient hospital care (90 days per illness episode), skilled nursing facility stays, and other services | $139 billion |

| Medicare Part B | 44 million (2010) | Physician visits and other health professional services | $102 billion |

| Program | Number of Americans Who Benefit | Principal Services Covereda | Program Payments (FY 2012 unless noted) |

| Medicare Advantage Program | 14.4 million (2013) | Part A and Part B benefits managed by local and regional health plans, with other services (hospice, drug coverage) optional, often for an additional premium | $123 billion |

| Medicare Part D | 36 million (2013) | Outpatient drug expenses through prescription drug plans (deductibles and cost sharing apply, except for low-income Americans) | $54 billion |

| Medicare Hospice Benefit (under Part A) | 1.2 million (2011) | Hospice-provided services related to a terminal illness | $14 billion (2011) |

| Medicare Home Health Care (under Parts A and B) | 3.4 million (2011) | Skilled care at home: nursing; physical, occupational, or speech therapy; medical social work; home health aide services | $21 billion |

|

Medicaid (federal and state) |

|||

| Medicaid Health Insurance | 14.8 million elderly people and people with disabilities (2013) | Inpatient and outpatient hospital care, physician and other professional services, and laboratory and radiology; all states except Oklahoma cover hospice care | $272 billion (2011) |

| Long-Term Care Assistance | 4.4 million adults (2011) | Nursing home and home health care | $125 billion (2011) |

| Assistance to Medicare Beneficiaries | 9.4 million Medicare beneficiaries | Medicare premiums and cost sharing, as well as uncovered services (especially long-term care) for “dual-eligible” people | $115 billion (2011) |

| Program | Number of Americans Who Benefit | Principal Services Covereda | Program Payments (FY 2012 unless noted) |

|

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)c |

|||

| Medical Care | 5.6 million veteran patients | Medical care, including long-term care, home care, respite care, and hospice/palliative care | $46 billion (2012) |

|

Private Insurance |

|||

| Usually through Employment-Related Plans for Employees and Retirees | 149 million nonelderly | Wide variation in coverage; almost 8 percent of hospice patients’ care is paid for by private insurance, compared with 84 percent paid for by the Medicare Hospice Benefit | $917 billion |

| Medicare Supplemental Insurance | 10.2 million | Mostly costs not covered by Medicare, such as deductibles, co-insurance, and co-payments | Information not available |

| Long-Term Care Insurance | 10 percent of the elderly | Nursing home and other long-term care services, depending on the policy | 4 percent of long-term care expenses |

NOTES:

aDoes not include some services, administration, public health, and investment.

bSome people receive benefits under more than one program.

cThe VA’s medical care category includes costs of medical services, medical administration, facility maintenance, educational support, research support, and other overhead items, but does not include costs of construction or other nonmedical support (http://www.va.gov/vetdata/Expenditures.asp [accessed December 16, 2014]).

SOURCES: MedPAC (payment basics): http://www.medpac.gov; Huskamp and Stevenson (see Appendix D); Medicare Part A and Medicaid enrollees: Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts (KFF, 2014); Medicare Part B: CMS “Medicare Enrollment: National Trends” (CMS, undated-a; KFF, 2013a); Medicaid Long-Term Care Assistance: AARP Public Policy Institute (2013), KFF (2013a); Private insurance: Martin et al. (2014); Medicare Supplemental Insurance: AHIP (2013); Long-Term Care Insurance: NBER (undated).

pertaining to these programs run to thousands of pages, and many of their key features are changing as a result of the ACA. As an example, the number of enrollees in the Medicaid program will rise substantially under the act as many states extend coverage to newly eligible residents (most of whom formerly lacked health insurance).

Medicare is the chief payer of care for people aged 65 and older with advanced serious illnesses and those who elect hospice. The committee calculated that in 2009, approximately 80 percent of U.S. deaths occurred among people covered by Medicare. This share has grown since the publication of Approaching Death (IOM, 1997), when Medicare covered approximately 70 percent of deaths (IOM, 1997, p. 155).

Medicaid is the most significant payer for care of low-income children with life-limiting conditions, and it paid more than two-fifths of the nation’s total bill for nursing home and other long-term care services in 2010 (KFF, 2013a,b). Additional funding for long-term care services comes from Medicare (for post-acute care), the Social Services Block Grant, the VA, Older Americans Act programs, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, other state programs, private insurance, and out-of-pocket spending. Families pay out of pocket for many expenses incurred in the last years of life. In a study of 3,209 Medicare beneficiaries, total health care expenditures in the 5 years before death not covered by insurance plans amounted to $38,688 for individuals and $51,030 for couples in which one spouse dies. For one-quarter of the families studied, these expenditures amounted to more than total household assets (Kelley et al., 2013b). Note that high out-of-pocket costs and severe financial impacts are not limited to families with elderly decedents. Recent research has highlighted the economic hardship—including work disruptions, income loss, and increased poverty—among families of children who have advanced cancer and those who die (Bona et al., 2014; Dussel et al., 2011).

One way or another, however, Medicare and Medicaid cover the great majority of people in the last years of life, present identifiable problems, and are clearly amenable to change through federal action. Consequently, this chapter focuses on these two programs.

PERVERSE INCENTIVES AND PROGRAM MISALIGNMENT

At the system level, the financial incentives driving the volume of services delivered and leading to fragmentation in the nation’s health care system are among the most significant contributors to unnecessarily high costs (Kamal et al., 2013). According to Elhauge (2010, p. 8), “The current payment system perversely provides disincentives for any provider to invest in coordination or care that might lessen the need of patients for health care, because . . . such investments result in fewer payments for medical or

hospital services.” These perverse incentives have led to a series of disconnected, siloed service programs, each with different payment, eligibility, and benefit rules and requirements.

Rigid silos of covered services are difficult for program managers, health care facilities, clinicians, and families to overcome when trying to meet the needs of a particular patient. In fact, one of the most burdensome problems patients and family caregivers face is the lack of coordination and communication among different components of the health care system. Not knowing whom to call or who is in charge of a patient’s care is deeply frustrating and adds unnecessary stress to already difficult situations (National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center, 2011). Default reliance on the emergency care system and on 911 calls adds risk of harm, burden, and cost. Table 5-2 summarizes how the financial incentives of public programs affect people with serious advanced illnesses.

Absent incentives and mechanisms for true integration across program eligibility, benefits, and financing, it will be impossible to achieve an effectively functioning continuum of care for people with advanced serious illnesses. This situation is in sharp contrast to the IOM’s “new rules to redesign and improve care,” which emphasize customization based on patient needs, with the patient, not the health system, as the source of control (IOM, 2001, pp. 61-62). Technical, political, and attitudinal barriers must be overcome to integrate funding streams and end cost shifting among programs. Whether recent health care reforms will be able to sufficiently realign current incentives remains to be seen.

Payer Policies and Costs of Care

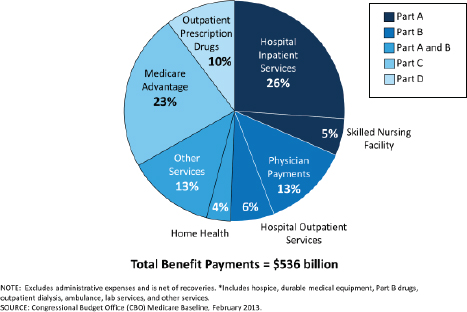

Since Medicare’s inception nearly half a century ago, doctors and hospitals have been reimbursed for the care they provide on the basis of fees for services performed. (Figure 5-1 shows a breakdown of Medicare benefit payments by type of service for 2012.) Fee-for-service payments reward the volume, not the quality, of services delivered. They remain the dominant financing model in U.S. health care despite a rising proportion of Americans in capitated health plans, including Medicare managed care (Medicare Advantage), and the growing number of salaried physicians (Kane and Emmons, 2013).

Generous fee-for-service payments give physicians incentives to—even in the final weeks of life—provide high-intensity, high-cost services, consult multiple subspecialties, order tests and procedures, and hospitalize patients. And because referring patients to hospice reduces the income of some other providers, the fee-for-service system discourages timely referrals to hospice. A study of more than 286,000 randomly selected fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries who died in 2009 found that although 42 percent

TABLE 5-2 How Financial Incentives in Public Programs Affect People with Serious Advanced Illnesses

| Program | General Payment Approach | Financial Incentives | Effects on People with Serious Advanced Illnesses |

| Medicare Part A (hospitals) | Fee-for-service, based on patient’s diagnosis and hospital’s cost experience | (1) Higher payments for more intensive services are an incentive to provide services and procedures; (2) fixed, diagnosis-based payments for an inpatient stay encourage early discharge, often to a skilled nursing facility | (1) May encourage overuse of services, even when nonbeneficial; (2) frail, very sick people experience multiple transfers from one care setting to another and increased rehospitalization rates |

| Medicare Part A (skilled nursing facilities) | Payment of a fixed per diem based on the seriousness of a resident’s condition | Patients cannot receive both skilled nursing and hospice care for the same condition; basing payment on patient acuity in theory encourages providers to capture the entirety of patients’ needs (although quality concerns remain) | 30 percent of Medicare beneficiaries receive “rehabilitative” care in a skilled nursing facility in the last 6 months of life, almost always after a hospital discharge |

| Medicare Part A (Medicare Hospice Benefit) | For 97 percent of days, hospices receive an all-inclusive per diem payment, not adjusted for case mix or setting or for outlier cases | (1) The hospice benefit is limited to people who have an expected prognosis of 6 months or less if the disease runs the expected course and who agree to forgo curative treatment for the terminal condition; (2) the program was designed mainly for care in the home (where room and board are not an issue) and does not take into account variable needs over time | (1) Survival is difficult to predict, and the limit creates “an artificial distinction between potentially life-prolonging and palliative therapies” (see Appendix D) as well as a psychological barrier to accepting hospice care; (2) if care is too complex for the home, transfer to a hospital and discharge to skilled nursing may appear to be the best option unless patients also have Medicaid (which pays for nursing homes) |

| Program | General Payment Approach | Financial Incentives | Effects on People with Serious Advanced Illnesses |

| Medicare Part B (physicians) | Fee-for-service | Encourages clinicians to provide more services and treatments | Excessive, high-intensity, and burdensome care that may not be wanted is provided in the last months and weeks of life |

| Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) | Capitation | (1) Plans are rewarded for efforts to manage chronic diseases effectively; (2) when patients enroll in hospice, they revert to fee-for-service Medicare | (1) Unnecessary and unwanted treatments, services, and hospitalizations may be reduced; (2) plans may be encouraged to promote hospice enrollment among high-need, high-cost patients |

| Medicare Part D (drugs) | Administered prices | Prescription drug costs are controlled | Less expensive products, often generic forms, are used when available |

| Medicaid Long-Term and Nursing Home Care | Acuity score assigned to each resident | (1) The acuity score method reduces incentives to avoid people with costly conditions; (2) Medicaid’s lower reimbursement for nursing home care is an incentive to hospitalize dual-eligible residents and return them to the facility under the higher-paying Medicare skilled nursing benefit | (1) Unknown (2) Individuals discharged from the hospital back to the nursing home under the skilled nursing benefit cannot receive hospice care concurrently for the same condition; a 2011 analysis suggested one-quarter of the hospitalizations for dual-eligible beneficiaries in the year studied (2005) were preventable, being due largely to the financial incentives for nursing homes to make these transfers (Segal, 2011) |

| Program | General Payment Approach | Financial Incentives | Effects on People with Serious Advanced Illnesses |

| Medicaid Home Health | For people eligible for nursing facility services; benefits vary | Intended to prevent excessively long periods of nursing home care | Unknown |

| Administration for Community Living (ACL) | $1.34 billion budget in 2013 for programs addressing health and independence, caregiver support, and Medicare improvements | Examples include elder rights services, the Alzheimer’s Disease Supportive Services Program, long-term care information, a family caregiver support program, nutrition services, and some support services | ACL’s goal is to increase access to community supports for older Americans and people with disabilities; it administers programs authorized under the Older Americans Act and Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act |

SOURCES: Appendix D; effects of skilled nursing facility benefit: Aragon et al. (2012), Segal (2011); ACL: http://www.acl.gov/About_ACL/Organization/Index.aspx (accessed December 16, 2014).

were enrolled in hospice at the time of their death, fully 28 percent were under hospice care for 3 days or less. More than 40 percent of late enrollments in hospice were preceded by an intensive care unit stay (Teno et al., 2013). The authors further compared these 2009 rates with patterns of care for similar numbers of Medicare beneficiaries in 2000 and 2005. Over the decade, the tendency to provide hospital and intensive care near the end of life appeared to be increasing.

Both liberals and conservatives find fault with the fee-for-service payment system (Capretta, 2013). The National Commission on Physician Payment Reform, established by the Society of General Internal Medicine in 2012, concluded that fee-for-service reimbursement is the most important cause of high health care costs and expenditures. The first of the commission’s 12 recommendations says, “Over time, payers should largely eliminate stand-alone fee-for-service payment to medical practices because of its inherent inefficiencies and problematic financial incentives” (Schroeder and Frist, 2013, p. 2029).

Nevertheless, fee-for-service is expected to remain a continuing and significant payment approach for many years to come (Wilensky, 2014). While Medicare and other payers will reimburse accountable care organizations (ACOs) established under the ACA through a graduated capitation

FIGURE 5-1 Medicare benefit payments by type of service, 2012.

SOURCE: KFF, 2012. Reprinted with permission from The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

approach, ACOs in turn will use fee-for-service methods to pay many physicians. The act therefore includes provisions to improve the fee-for-service system, revising the physician fee schedule and better reflecting the relative value of resources expended (Ginsburg, 2012).

The Hospital Environment

Hospital Care

As noted in Approaching Death (IOM, 1997, p. 96), “curing disease and prolonging life are the central missions of [hospitals]. Hospital culture often regards death as a failure.” While hospital and intensive care undoubtedly saves the lives of a great many otherwise healthy people, it is not necessarily useful—and is, to the contrary, harmful—for people with advanced and irreversible chronic illnesses. Yet it is hospital care, not community- or home-based care, that consumes the largest share of Medicare spending for patients in the final phase of life: fully 82 percent of all 2006 Medicare spending during the last 3 months of life was for hospital

care, despite the known risks and costs of such care and despite widespread patient preferences, noted in earlier chapters of this report, for less intensive and more home-based services (Lakdawalla et al., 2011).

The transitions between care sites—from hospital to home or nursing home and back again—encouraged, as discussed earlier in this chapter, by the current payment system, put patients at risk (Davis et al., 2012). Resulting higher rates of infection, medical errors, delirium, and falls are collectively captured by the term “burdensome transitions” (see Chapter 2), and they are increasingly common near the end of life. Earlier death may also result from these transitions. The average (mean) number of transitions from one site of care to another in the last 90 days of life increased from 2.1 per decedent in 2000 to 3.1 in 2009, and more than 14 percent of these took place in the last 3 days of life (Teno et al., 2013). This high rate of transitions between care settings is costly and inconsistent with high-quality care.

Emergency Services

When emergency medical services (EMS) providers respond to a 911 call for a Medicare patient, they are required under current Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) policies (generally followed by private insurers as well) to transport the patient to a hospital as a condition for being paid for their response. As a result, patients who might better be served by a palliative care home visit or a trip to a primary care clinician, if such services were available, end up being treated in an emergency department (Alpert et al., 2013).9 Pain and other unmanaged symptoms prompt many of these visits.

Fifty percent of older Americans visit the emergency department in their last month of life, and 75 percent do so in the last 6 months of life; in 77 percent of cases, the visit results in hospitalization (Smith et al., 2012). Approximately 1.1 million EMS transports are covered by Medicare annually, at a cost of some $1.3 billion.

Unnecessary and burdensome EMS transports represent poor-quality care for people with advanced serious illnesses. When they present at the emergency department, they may be admitted to inpatient care because of an unclear diagnosis; the severity of symptom distress; caregiver concerns; and, most important, a lack of prior clarification of achievable goals for care. Emergency departments are experiencing a growing number of visits by elderly patients whose mix of serious medical conditions, cognitive impairments, functional dependencies, complex medication regimens, and

_______________

9Recent growth in hospital admissions has been attributed entirely to emergency department admissions, which increased by 2.7 million between 2003 and 2009 (Kellermann et al., 2013).

caregiver exhaustion make high-quality emergency care extremely difficult (Hwang et al., 2013).

Many terminally ill patients return to the emergency department because they have not been informed and do not know that they are dying or that there are no effective treatments for their underlying disease (Mitchell et al., 2009). They may be unaware of care alternatives, such as physician house calls, community-based palliative care, or hospice. If EMS providers had more options available to them—other than not being paid—when they respond to overwhelmed caregivers who have panicked and called 911, emergency transfers to hospitals might be avoided. Communities are testing new approaches to training and paying EMS personnel to assess and intervene with soluble problems at home, such as a fall without evidence of injury, rather than routinely transporting all patients who call 911 to the emergency department. Improved “geriatric emergency services” and other models for providing more in-home care and forestalling 911 calls are being tested (Hwang et al., 2013).

The use of emergency services near the end of life is not limited to elderly individuals. Parents of uninsured or publicly insured children with serious illnesses often face delays in obtaining physician appointments and end up seeking care in the emergency department, or they may be referred there by their primary care clinician (Rhodes et al., 2013). In some parts of the country, critically ill children are stabilized at a general emergency department, where experience in recognizing a rapidly worsening condition may be lacking, before transfer to a specialized children’s hospital for further care (Chamberlain et al., 2013).

Medicaid reimbursement policies, such as lesser payment for ambulatory versus emergency department care, give hospitals incentives that favor care in the emergency department instead of the hospital’s primary care or pediatric clinic (Chamberlain et al., 2013). Finally, once a child is in the care system, fee-for-service reimbursement and the greater malpractice litigation concerns associated with pediatric care may create incentives to overtest and overtreat (Greve, 2011).

The Ambulatory Care Environment

Physician Services

As the gatekeepers for almost all other services, physicians are among the most important players in end-of-life care. Under Medicare, beneficiaries may see a physician as many times as they wish during a year. However, they may be responsible for a 20 percent co-payment for every visit after paying the deductible of $147 (as of 2014). Part B Medicare imposes no

restrictions on the type or number of physicians a beneficiary may visit (CMS, undated-c).

Physicians’ end-of-life care often fails to meet the needs of patients and families because some clinicians may

- provide care that is overly specialized and does not address the multiplicity of a patient’s diseases or the emotional, spiritual, family, practical, and support service needs of patients and their caregivers;

- continue disease treatments beyond the point when they are likely to be effective;

- fail to adequately address pain and other discomfort that often accompanies serious chronic illnesses and the dying process; and

- fail to have compassionate and caring communication with patients and family members about what to expect and how to respond as disease progresses (Weiner and Cole, 2004; Yabroff et al., 2004).

These problems have numerous causes. Shortcomings in physician education regarding end-of-life care are covered in Chapter 4. In addition, the overall culture of medicine is focused on curing acute medical problems. Reflecting and reinforcing this tendency, the financing structure of Medicare and other insurance programs rewards the performance of a high volume of services and the administration of well-reimbursed treatments and procedures rather than encouraging the provision of palliative and comfort care.

As noted earlier, the general financial incentive within fee-for-service is to see as many patients as possible and to perform multiple procedures. In addition, Congress in 1989 created a physician fee structure of “relative value scales” that takes into account primarily physician time, intensity of service, malpractice insurance, and a geographic factor. Medicare, Medicaid, and many private insurers use this system, which also financially rewards more complex specialty procedures without regard to patient benefit or cost (MedPAC, 2011). At the same time, the system undervalues the evaluation and management services necessary to help patients and families understand what to expect, to explain the pros and cons of treatment options, and to establish goals for care as a disease evolves (Kumetz and Goodson, 2013).

Annual increases in Medicare’s reimbursements to physicians are, in theory, tied to growth in the nation’s GDP. This adjustment method, established by Congress via the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and called the “sustainable growth rate” (SGR), was intended to be cost-saving. Opposition to limiting physician fee increases has been so strong, however, that

Congress has not imposed these controls since 2002.10 Medicare payment rates for physicians already are about one-fifth lower than private insurance rates (Hackbarth, 2009), and any large additional reduction could lead many physicians to stop accepting new Medicare beneficiaries into their practices (MedPAC, 2011). Because the SGR approach could jeopardize older Americans’ access to care, it is politically unpalatable, and because it fails to incentivize higher-quality care or control health care spending, it is deemed unrealistic and outmoded (Guterman et al., 2013; Hackbarth, 2013; MedPAC, 2011). Discussion of its repeal continues.

Other Services

Although Medicare does not cap beneficiaries’ hospital admissions or medical and surgical procedures, it does cap payments for ancillary services that might substantially benefit certain people nearing the end of life—often more so than acute care and procedures. Such services may forestall hospitalizations, help people better manage daily activities, and improve both health status and quality of life (Eva and Wee, 2010; Farragher and Jassal, 2012). Limitations on rehabilitation services (including those that aid in mobility, swallowing, and communication) may therefore have unintended adverse consequences for both quality of care and health care costs if patients’ remediable problems are not addressed.

Depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues are a significant concern at the end of life and may combine with cognitive problems to cloud a person’s last months. Federal rules implementing mental health parity legislation have erased most long-standing differences between coverage of mental health and other health services for patients with Medicaid and those covered by large group health insurance plans (SAMHSA, 2013); Medicare will reimburse outpatient mental health treatment (therapy and medication management) at parity with other Part B services beginning in 2014.11 Whether mental health services will actually become available re-

_______________

10The SGR distorts the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) estimates of future health care costs. CBO is required to base its estimates on current law, and the SGR is current law, even though it is unenforced. In discussing future federal health spending, the Simpson-Bowles commission said, “These projections likely understate [the] true amount, because they count on large phantom savings—from a scheduled 23 percent cut in Medicare physician payments [in 2012; larger thereafter] that will never occur” (National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, 2010, p. 36). The commission made reforming the SGR its first recommendation in the health arena.

11In addition, drug plans operating under Medicare Part D must cover certain classes of drugs, including antidepressants and antipsychotics. Certain intensive mental health services—such as psychiatric rehabilitation and psychiatric case management—are not covered (Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, 2012).

mains to be seen, however, as many mental health care providers (including psychiatrists) do not accept insurance at all (Bishop et al., 2014).

The Managed Care Environment

Managed care was developed and tested in the early 1970s as a way of improving the quality and affordability of health care through capitated, integrated provider networks; an emphasis on disease prevention; utilization review for high-cost services; and other means. In the approach’s simplest formulation, managed care organizations receive capitated payments—that is, an annual fixed dollar amount for each individual enrolled in the plan (i.e., per capita).12 For that fee, enrollees receive all their physician care, hospital care, emergency services, and many other covered benefits, depending on what is included in a specific plan. The managed care organization negotiates with providers to achieve reasonable charges and contracts with (or even hires) physicians. Capitation, in theory, switches incentives toward keeping enrollees healthy and avoiding costly overtreatment.

Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) plans are managed care plans offered by private insurance companies that cover all Part A and Part B services. In 2012, Medicare Advantage accounted for 23 percent of all Medicare expenditures (see Figure 5-1). Unlike Medicare fee-for-service, Medicare Advantage gives physicians a financial incentive to recommend hospice for patients nearing the end of life because when plan members enroll in hospice, fee-for-service Medicare becomes the payer. This hospice “carve-out” makes it attractive for a plan to shift patients likely to be high-cost from its rolls to the Medicare Hospice Benefit, but also decreases the incentive for the plan to develop high-quality palliative care services (see Appendix D).

In general, health insurance, including managed care programs, may contain disincentives to enroll people who are the very sickest and costliest. Such initiatives require careful risk stratification and monitoring to ensure adequate access and protection for these beneficiaries.

Just as Medicare, through Medicare Advantage, has embraced managed care partly as a way to avoid the costs of unnecessary hospitalizations, Medicaid has embraced managed care partly to avoid unnecessary nursing home admissions. Ideally, these capitated environments should provide models of care and financing that best meet the needs of program beneficiaries, especially those eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid

_______________

12Payments might include some adjustments, such as for patient age and health status or local cost of living. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 included risk adjustment, based on patients’ diagnoses, to encourage managed care organizations to enroll the sickest Medicare beneficiaries.

(CMS, 2013b). However, the development of policies for implementing and ensuring the quality of managed care options for the dual-eligible population is hampered by significant data limitations, including a lack of timely Medicaid data and comprehensive information about dual eligibles enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans (Gold et al., 2012).

An evaluation of nine state programs of integrated care for dually eligible beneficiaries, performed for MedPAC, identified several additional barriers to the development of managed care programs:

- Enrolling beneficiaries in managed care is problematic because of a lack of awareness of such programs, which may contribute to opposition from providers, beneficiary advocates, and others.

- Structural design problems include administrative leadership (through Medicare Advantage rather than state Medicaid programs), complications in providing patients with social supports and behavioral health services, and uncertainty regarding whether to create separate programs for people under age 65.

- Conflicting Medicare and Medicaid eligibility, coverage, and provider rules complicate state efforts to initiate such programs (Verdier et al., 2011).

Despite these barriers, models of managed care for dually eligible individuals have shown promise, even if they have not been widely replicated. The Evercare model, implemented in five nursing homes (Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Colorado [Denver/Colorado Springs], and Tampa) and involving more than 3,600 patients (half enrolled in Evercare, half receiving usual care), offered a capitated package of Medicare-covered services and intensive primary care by nurse practitioners for long-stay, frail, chronically ill nursing home patients. Services included customized care planning, coordination, and delivery. Evercare paid nursing homes an extra fee for “intensive service days” to handle cases that might otherwise have required hospitalization; this measure contributed to a 50 percent reduction in the hospitalization rate for enrollees compared with the usual care group. For those who were hospitalized, stays were shorter for the Evercare group. Evercare enrollees also had one-half the rate of emergency room visits of the usual care group and received more physician visits and mental health services (Kane et al., 2002).

Similarly, an 18-month cohort study of 323 residents with advanced dementia in 22 Boston-area nursing homes found that managed care enrollees had higher rates of do-not-hospitalize orders, primary care visits, and nurse practitioner visits and lower rates of burdensome transitions and hospitalizations for acute illnesses compared with traditional fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries—all suggesting higher-quality care. Rates of

survival, comfort, and other outcomes did not differ significantly between the two groups (Goldfeld et al., 2013).

Finally, the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) offers a comprehensive service package designed to avoid nursing home placements. The program was established as a type of provider for Medicare and Medicaid through the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. PACE serves primarily dual-eligible individuals with chronic illnesses who are aged 55 and older. It uses a centralized, nonprofit provider model rather than a looser network of independent practitioners to provide medical and other clinical services along with the kinds of supportive and personal care services discussed later in this chapter—such as meals, transportation to day centers or other facilities, and in-home modifications.

In 2014, 31 states offered the PACE program. Data from 95 of the nation’s 103 PACE projects indicate they serve a total of slightly more than 31,000 people (National PACE Association, 2014). Thus, the PACE program remains small, and its effectiveness in serving the specific needs of the population requiring palliative care or those nearing the end of life has not been established (Huskamp et al., 2010; see also Appendix D). Moreover, a recent analysis found that, although PACE improves quality by effectively integrating acute care and long-term community supports and reducing hospitalizations, it has not reduced Medicare expenditures for beneficiaries with substantial long-term care needs, perhaps because capitation rates have been set too high (Brown and Mann, 2012).

The slow rate of PACE expansion has been attributed to regulatory and financial constraints, poor understanding of the program among referral sources, competition, and rigid structural characteristics of the program model (Gross et al., 2004). PACE is a comprehensive approach, and it requires a sophisticated infrastructure. Enabling PACE to be implemented more widely might require designing ways to expand it to the non-Medicaid population, as well as other measures (Hirth et al., 2009).

The Palliative Care and Hospice Environment

A full description of the services involved in and benefits of palliative care, including hospice, is provided in Chapter 2. This section addresses the costs of palliative care and hospice compared with usual care and the policies that regulate the organization and provision of palliative care and hospice services.

Palliative Care

Palliative care programs focus on relieving the medical, emotional, social, practical, and spiritual problems that arise in the course of a serious

illness. Many seriously ill people—not just those nearing the end of life—can benefit from palliative care, and it can be provided in many settings, including the home and the nursing home. In hospitals, palliative care teams work alongside treating physicians to provide an added layer of support for patients and their families, focusing on expert symptom management, skilled communication about what to expect, and planning for care beyond the hospital. As discussed in Chapter 2, hospital-based palliative care has grown significantly in the past two decades (CAPC, 2011, 2013).

Palliative care is sometimes viewed as an alternative to what has been termed “futile care”—that is, interventions that are unlikely to help patients or be of marginal benefit and may harm them. Although identifying which treatments are of marginal benefit may be subjective, a study conducted in one academic medical center found that critical care clinicians themselves believed almost 20 percent of their patients received care that was definitely (10.8 percent) or probably (8.6 percent) futile (Huynh et al., 2013). These opinions were based on four principal rationales: the burden on the patient greatly outweighed the benefits, the treatment could never achieve the patient’s goals, death was imminent, and the patient would never be able to survive outside the critical care unit. The total annual cost of futile treatment for the 123 (10.8 percent of) patients who received futile care was estimated at $2.6 million.

At the age of 84, my mother arrived at the emergency room [ER] in significant pain. During the preceding 3 weeks, she had contacted her health care provider several times about nausea and been assured it was not significant. Within 36 hours of arriving at the hospital, she was diagnosed with severely metastasized cancer, especially the liver and including her bones. Even though the source of the cancer had not yet been identified and no one had discussed the reasonableness of pursuing treatment, a port was installed in her chest for chemotherapy, “just in case.” In the next couple of days, as further testing was done, she had an instance of unstable heartbeat and was taken to ICU, where she was given medication and her heart rate returned to normal. The hospital cardiologist assured us her heart was not a problem, but that he would see her every day while she remained in the hospital. Why? All medical staff consistently pushed ahead with an attitude that chemotherapy WOULD be pursued, that they would get her well enough to go home and return for outpatient chemo, and no one ever raised the issue of whether such an approach would be futile. My sister and I had to press the doctor intensely to get him to acknowledge that even with chemo, her life expectancy was well less than a year.

Her condition did not improve over her stay, and 1 week later she decided not to pursue treatment (after several bouts of explosive diarrhea and an inability to get out of bed) and went home in hospice care. She died 2 weeks to the day after going to the ER. Even when leaving the hospital, they did not suggest the end was imminent. She had a great deal of testing, implantation of a PIC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line, and yet no reasonable analysis of the value of further care from anyone.*

____________

*Quotation from a response submitted through the online public testimony questionnaire for this study. See Appendix C.

The committee agrees with Parikh and colleagues’ (2013, p. 2348) opinion that while “cost savings are never the primary intent of providing palliative care to patients with serious illnesses . . . it is necessary to consider the financial consequences of serious illness.” Much of the spending on the sickest Medicare beneficiaries is attributable to hospital care. Hospitals with specialty palliative care services have been able to reduce their expenditures through shorter lengths of stay in the hospital and in intensive care and lower expenditures on imaging, laboratory tests, and costly pharmaceuticals. In addition, patients receiving hospital-based palliative care have been shown to have longer median hospice stays than patients receiving usual care (Gade et al., 2008; Morrison et al., 2008; Starks et al., 2013).

Most studies comparing the costs of palliative and usual care have been conducted in the hospital setting, but the differing approaches, methods, and rigor of these studies make their findings difficult to compare. Nevertheless, research using robust methods to assess many of the more mature U.S. palliative care programs shows a pattern of savings and demonstrates the substantial excess costs associated with usual care (see Tables 5-3 and 5-4). A 2012 Canadian literature review13 similarly found that hospital-based palliative care teams reduce hospital costs by $7,000 to $8,000 per patient and reduce the cost of end-of-life care by 40 percent or more (Hodgson, 2012).

Palliative care provided in nonhospital settings has also been found to yield cost savings. A systematic review examined studies of palliative care—cohort studies (34), randomized controlled trials (5), nonrandomized trials (2), and others (5)—published between 2002 and 2011 and conducted variously in hospital-based, home-based, and other program settings. Two-

_______________

13In 2012, the Canadian government allocated $3 million over 3 years to support the development and implementation of a framework for community integrated hospice and palliative care models. The Way Forward initiative is led by the Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada and managed by the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association.

TABLE 5-3 Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing the Costs of Palliative and Usual Care

| Study (Period Studied) | Number of Patients and Setting | Excess Cost of Usual Care | Other Findings |

| Gade et al., 2008 (2002-2003) | 517 patients in three hospitals receiving interdisciplinary palliative care services (275 patients) or usual care (237) | Excess 6-month post-hospital discharge costs of $4,855 for each usual care patient (p = 0.001) | Greater patient satisfaction with the care experience and provider communication in the palliative care than in the usual care group; also median hospice stays of 24 versus 12 days, respectively |

| Brumley et al., 2007 (2002-2004) | 145 late-stage patients who received in-home palliative care versus 152 who received usual care in two group-model health maintenance organizations in two states | Excess costs of $7,552 for each usual care group member (p = 0.03) | Palliative care recipients were 2.2 times more likely than usual care recipients to die at home and had fewer emergency department visits and hospitalizations; survival differences between the two groups disappeared after data were adjusted for diagnosis, demographics, and severity of illness (Personal communication, S. Enguidanos, University of Southern California, February 25, 2014) |

| Greer et al., 2012 (2006-2009) | 151 patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer receiving usual outpatient oncologic care with or without early palliative care comanagement | Excess overall costs of $2,282 per patient among those receiving usual care only | Patients receiving early palliative care had significantly higher quality of life, experienced fewer depressive symptoms, were less likely to receive chemotherapy within 2 weeks of death, had earlier hospice enrollment, and survived 2.7 months longer |

TABLE 5-4 Observational Studies Comparing the Costs of Palliative and Usual Care

| Study (Period Studied) | Number of Patients and Setting | Excess Cost of Usual Care | Other Findings |

| Morrison et al., 2008 (observational study using propensity score matching, 2002-2004) | 4,908 patients who received palliative care consultations and 20,551 who received usual care in eight geographically and structurally diverse hospitals | Excess total costs of $2,642 for each usual care patient discharged alive (p = 0.02) and $6,896 for each who died in the hospital (p = 0.001) | Intensive care unit (ICU), imaging, laboratory, and pharmacy costs were higher among the usual care patients |

| Morrison et al., 2011 (observational study using propensity score matching, Medicaid-only patients, 2004-2007) | 475 patients who received palliative care consultations and 1,576 who received usual care in four diverse urban New York State hospitals | Excess costs of $4,098 for each usual care patient discharged alive (p <0.05) and $7,563 for each who died in the hospital (p <0.05) | Patients receiving palliative care consultation were more likely than usual care patients to be discharged to hospice (30 percent versus 1 percent) and less likely to die in intensive care (34 percent versus 58 percent) |

| Starks et al., 2013 (observational study using propensity score matching, 2005-2008) | 1,815 patients who received palliative care consultation and 1,790 comparison patients from two academic medical center hospitals | Excess costs of $2,141 for usual care patients with lengths of stay of 1-7 days (p = 0.001) and $2,870 for usual care patients with lengths of stay of 8-30 days (p = 0.012) | Some differences between palliative care and usual care groups remained |

| Penrod et al., 2010 (observational study, 2004-2006) | 606 veterans who received palliative care and 2,715 who received usual care in five U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals | Excess costs of $464 per day for usual care patients (p = 0.001) | Instrumental variables method used to account for unmeasured selection into treatment bias (Stukel et al., 2007) |

thirds of the studies were based in the United States, and the remainder were conducted internationally, in widely differing health systems. The authors found that, although the studies used a broad variety of utilization, cost, and outcome measures and employed different specialist palliative care models, palliative care was “most frequently found to be less costly relative to comparator groups, and in most cases, the difference in cost is statistically significant” (Smith et al., 2014, p. 1).

A recent review of published, peer-reviewed outcomes research on nonhospice outpatient palliative care, which included four randomized interventions and a number of nonrandomized studies, concluded that outpatient palliative care produced overall health care savings resulting from avoidance of expensive interventions. The authors suggest that such savings are “especially important in systems of shared cost/risk, integrated health systems, and accountable care organizations” (Rabow et al., 2013, p. 1546).

Community-based pediatric palliative care has also been found to produce positive patient and family outcomes, as well as cost savings (Gans et al., 2012), or at least to be relatively low cost (Bona et al., 2011).

These data across varying types of studies and care settings indicate potential savings from palliative care consultation and comanagement in hospitals and suggest savings in other settings as well. Additional research is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn on the impact of palliative care delivery on total health care spending.

Hospice Care

The Medicare Hospice Benefit is the one public insurance program intended specifically to serve beneficiaries within the last few months of life. Under this benefit, the enrolled beneficiary pays no charge for services received except for small deductibles for drugs and respite care. Most services are provided in the patient’s home by visiting nurses, with variable additional support from physicians, social workers, personal care aides, and others. For fiscal year 2014, Medicare’s daily hospice reimbursement rates were as follows: for routine home care, $156.06; for continuous home care, $910.78; for general inpatient care, $694.19; and for inpatient respite care, $161.42 (HHS and CMS, 2013).14 In addition, the total amount of Medicare payments a hospice provider is allowed to receive in a single year is capped according to a defined formula.

As described in Chapter 2, hospice services produce many benefits for patients and families. Matched cohort studies demonstrate that hospice

_______________

14Minus a two percentage point reduction to the market basket update for hospices that fail to submit the required quality data.

care enhances the quality of care, helps patients avoid hospitalizations and emergency visits, prolongs life in certain groups of patients, improves caregivers’ well-being and recovery, and in some reports appears to reduce total Medicare spending for patients with a length of hospice service of under 105 days (Kelley et al., 2013a).15

Enrollment disincentives Built into the Medicare Hospice Benefit and its payment rules are several policies that are intended to manage program costs but may work against the needs of patients with advanced serious illnesses and their families. Two eligibility requirements meant to limit the number of people who qualify for the hospice benefit are

- an expected prognosis of 6 months or less if the disease runs the expected course, as certified by two physicians16; and

- an agreement, signed by the beneficiary, to give up Medicare coverage for further treatments aimed at achieving a cure.

For many patients, these criteria have discouraged use of the benefit until the final days or hours of life and, according to Approaching Death, exclude “many [people] who might benefit from hospice services” (IOM, 1997, p. 169). The ban on “curative” treatments may also disadvantage patients with organ failure, for whom life-prolonging and palliative treatments—such as diuretics for people with heart failure—often are the same. In addition, physicians, patients, and family members alike may be unwilling to accept a prognosis of a few months—particularly given the uncertainty in predicting mortality for diseases other than cancer—or to abandon cure-oriented treatment (Fishman et al., 2009). These factors contribute to the brevity of hospice stays: the median length of stay in hospice is 18 days, and fully 30 percent of hospice beneficiaries are enrolled for less than 1 week. Still, the number of Medicare beneficiaries enrolling in the Medicare Hospice Benefit more than doubled between 2000 and 2011, from 0.5 million to more than 1.2 million (MedPAC, 2013).

Some hospice champions contend that the 6-month limit and the ban on cure-oriented treatments make the Medicare Hospice Benefit “a legal barrier to improving integration and collaboration across the health system” (Jennings and Morrissey, 2011, p. 304). In a survey of nearly 600

_______________

15Methodological difficulties in analyses of hospice savings include the lack of controlling for selection bias (that is, people who choose hospice care may be different in some way from those who do not) and the impact on the data of both very-long-stay patients and those discharged alive after very long stays, who may have been more appropriate candidates for long-term care programs rather than hospice.

16In reality, patients are able to receive hospice services for longer than 6 months if, at the end of the period, they receive a physician recertification of the 6-month prognosis.

hospices, 78 percent were found to restrict enrollment in some way, such as by declining to admit patients with ongoing disease treatment needs or without a family caregiver at home (Aldridge Carlson et al., 2012). Small hospices are especially likely to restrict enrollment (Wright and Katz, 2007).

I am a registered nurse case manager, certified in palliative nursing, working with hospice patients in their homes. I think the single most effective change that could be brought about would be to extend the hospice benefit to a 1-year prognosis rather than the current 6 months. This may allow for a strengthening of the role of palliative care much earlier in the trajectory of life-limiting illnesses, particularly those for which the expected course is more certain, such as some cancers. I think the earlier the concept of palliative care is introduced, the less intimidating the “end-of-life” connotation of hospice will be. A patient’s course would feel more of a continuum, rather than the abrupt shift from treatment to “hopelessness” that now exists. Just last week, I had a visit with a woman who had been referred to hospice by her oncologist, and she was very frightened that her death was imminent, even though it is not. Her family was equally upset with the physician for frightening the patient so.*

____________