5

Lessons from Social Movements Beyond Health

The workshop’s second panel, moderated by Winston Wong of the Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity and the Elimination of Health Disparities, featured social movement practitioners from different fields who shared their perspectives on how movements are built and how social change is accomplished. Although some presenters discussed work that encompasses health equity—and in so doing, connected their experiences to observations made by previous speakers—these panelists generally placed health within the broader context of social empowerment, economic justice, democratic self-government, and equal rights.

COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND EDUCATION

Karoleen Feng, community development manager for the Mission Economic Development Association (MEDA),1 described MEDA as an organization that for nearly 40 years has worked to achieve economic justice for the low- and moderate-income Latino residents of San Francisco’s Mission District. Over that time, MEDA has grown from its initial focus on small business technical assistance to broad-based asset building, including recent expansion to include education. MEDA, she said, has a history of success in community planning and building cross-sector networks of partners beyond economic development. “We are good at raising funds,”

____________

1 See http://medasf.org/home (accessed June 13, 2014).

she said, adding that such funding generally benefits the work of partner agencies as well as MEDA.

Since the founding of MEDA, the once predominantly Latino population of the Mission District, which comprises approximately 60,000 people within an area of 20 square blocks, has diversified. Today, according to Feng, 41 percent of Mission residents are Latino, 40 percent white, 12 percent Asian, and 3 percent black; a total of 40 percent of all residents are foreign-born. Median family income in the Mission District is nearly $68,000, but there is significant disparity among its residents, with Asian and white families earning about $85,000 annually as compared with $45,000 for Latino families. Feng noted that, across the United States, the net worth of white families is approximately 18 times that of Latino families.

Feng highlighted information that illustrates the connection between poverty and health in the Mission District:

- One-third of students do not have a medical home, with first- and second-graders least likely to have access.

- Less than one-quarter of students meet criteria for healthy weight and height for their age.

- Fourteen percent of families with children live in poverty; of them, 68 percent are Latino.

- More than one-third of Latino adults in San Francisco work in low-wage jobs (paying $10-$15 per hour).

In addition to poverty and health, other challenges Mission District residents face, Feng observed, including low academic achievement and limited access to technology.

The Mission Promise Neighborhood

In 2012 MEDA was awarded 1 of 12 5-year grants from the U.S. Department of Education, designating the Mission District as a Promise Neighborhood.2 Feng described the Mission Promise Neighborhood (MPN)3 effort as culturally relevant, place-based, and focused on the academic achievement of children and the economic success of families. “We feel if you don’t alleviate poverty, if you don’t change the income levels of families and help them to build assets, you will not change” the futures of their children, she explained. To address this goal, the MPN integrates

____________

2 See http://www2.ed.gov/programs/promiseneighborhoods/index.html (accessed June 13, 2014).

3 See http://missionpromise.org (accessed June 13, 2014).

a spectrum of services for residents and coordinates with many partner agencies in order to maximize the collective impact. Feng shared the following vision statement, which reflects MPN’s broad goals:

The Mission Promise Neighborhood builds a future where every child excels and every family succeeds. Students enter school ready for success, and graduate from high school prepared for college and career. The Mission District thrives as a healthy and safe community that provides families and their children the opportunity to proser economically and to call San Francisco their permanent home.

Feng also described the MPN mission statement that explains the strategy for reaching the vision:

The Mission Promise Neighborhood links family economic security with student academic achievement. It creates a comprehensive, integrated framework of evidence-based services that responds to urgent needs and builds on the foundation of student, family, community, and school strengths and assets. Together, parents, neighbors, and partner organizations work block by block, guaranteeing that all Mission children, youth, and their families achieve academic excellence and economic self-sufficiency.

Feng identified four ingredients to achieving the goal of academic achievement and economic success: Spanish language capacity; cultural relevance; needs-based, evidence-based services; and service integration.

Integrating Services to Support Success

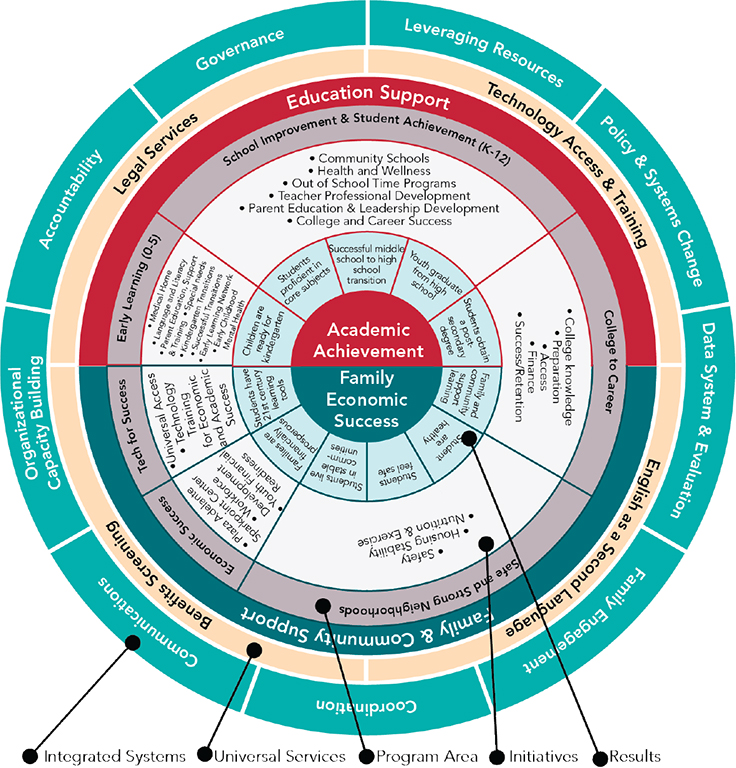

Feng described the numerous diverse services that MEDA and its 26 partners provide in order to accomplish the MPN vision. According to the project’s strategic planning framework (see Figure 5-1), in addition to the “universal services that everybody has to get,” such as instruction in English as a second language, benefits screening, and legal services, there must also be collective efforts toward systematic improvements in such areas as communication, family engagement, policy, and governance. The two primary goals—academic achievement and economic success—underlie all the other goals, she said. For example, they help to build assets that allow residents to take personal responsibility for their health.

Feng described how typical MEDA clients might experience service integration as part of the MPN. For example, those who come to MEDA’s headquarters at Plaza Adelante for help with tax preparation are also offered information on starting a business and becoming homeowners, along with the necessary financial education. Clients are asked about the financial challenges they face, for which they may receive assistance from MEDA—including individual family coaching—or they may be referred to MEDA’s partners as appropriate. Plaza Adelante also incorporates a

FIGURE 5-1 Mission Promise Neighborhood “wheel of promise” strategic framework.

SOURCE: Feng presentation, December 5, 2013.

technology center that serves both residents and neighborhood schools, all of which have traditionally been among the state’s poorest performers and are recent recipients of improvement grants, she said.

MEDA employs a broad range of metrics to measure the effects of its programs on family economic success, Feng said. MEDA gathers data on a variety of indicators, including income, credit scores, savings, and debt-to-income ratios; employment, job creation, and business expansion; home purchase, foreclosures, and affordable housing availability; and obtaining tax refunds and public benefits. In addition to using their results to attract further funding, MEDA is building its own evidence base through evaluation, she said.

TACKLING HEALTH INEQUITY BY BUILDING DEMOCRACY

Doran Schrantz, executive director of ISAIAH,4 described her Minnesota-based organization as a “faith-based community organization of 100 member congregations” and “a vehicle for people of faith to act collectively and powerfully for racial and economic justice.” ISAIAH is also affiliated with a national network of organizations involved with racial, economic, and social justice called People Improving Communities through Organizing (PICO). Both ISAIAH and PICO are examples of structures that mobilize people to take action on the conditions that affect them and their communities, she said.

Although it is not originally directed toward achieving public health objectives, ISAIAH’s organizing work has increasingly involved health issues because of its interest in social conditions, Schrantz said, and she quoted two definitions that have guided work in this area. The World Health Organization defines the social determinants of health as “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, including the health system,” and it also notes that “these circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels” (WHO, 2014). The second definition she mentioned appeared in the IOM report The Future of Public Health (IOM, 1988, p. 1): “Public health is what we as a society do collectively through organized actions to assure the conditions in which all people can be healthy.”

Elements of Community Organizing

Referring to Iton’s characterization of social conditions that result in health consequences, Schrantz described ISAIAH’s mission as one of helping vulnerable populations build the necessary capacity to engage in

____________

4 See http://isaiahmn.org (accessed June 13, 2014).

democratic self-governance as a path toward better health through better living conditions. “Health is the condition in which we live,” she stated. “People can impact the conditions in which they live if they have the capacity to act on those conditions.” Although social movements do not just happen, as Polletta noted, Schrantz observed that the mobilization of people to act—the building of democratic self-governance—requires difficult and skilled work that often remains invisible. Every grassroots protest, demonstration, or march involves, she said, “months and months of infrastructure building, months of leadership development, months of strategy conversations.” Organizing requires a great deal of training, a unique set of skills, and experience. People talking to people about what they value is central to building a social movement, she continued, and it is far more demanding than is widely appreciated.

What happens in these conversations? Community organizers learn what matters to community members and help them build the necessary skills and strategy to acquire the power to change their communities for the better, Schrantz said. She described three components of community organizing, which she depicted as interconnecting cogs driving the larger mechanism of change. The first component, grassroots leadership development, is critical to any community-led process. On this foundation, organizers strive to build the second component: democratic, accountable, sustainable, community-driven organizations, whose participants are “exercising democracy with each other.” “Every aspect of a powerful community organization allows people to practice at every level of it what it feels like to lead and to make decisions,” she said.

The third component of community organizing, the theory of change, postulates that the power or the ability to act drives change. “The reason why there is a struggle for resources, for scarce social goods, is that there are differentials in power,” Schrantz explained. “Differentials in power do not change because somebody else who has more power gives it to you. Differentials in power change because you take ownership and collective and community responsibility for negotiating for the power and the resources you need. When that power structure is in place, that is when change happens.”

Grassroots Leadership Development

Among ISAIAH’s many accomplishments, the most important is also the most difficult to describe to people not directly involved in community organizing, Schrantz said. It is the work of stimulating the emergence of community leaders as they “begin to imagine the reality that their story could be at the center of politics”—a process she described as “deeply transformative,” even “sacred.” Most importantly, she concluded, it lies

at the heart of social movements, because “no amount of policy change or even structural change will be sustainable until people are really the agents of their own lives.”

BUILDING SOCIAL MOVEMENTS FROM THE BOTTOM UP

“I stand here before you because of organizers,” said Martha Argüello, executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility–Los Angeles (PSR–LA).5 What she learned from the work of the Black Panthers and others who taught her the basics of community organizing as a teenager saved her life, she said, and set her on a path of “leadership development that has always been in opposition and in fighting for my place at the table.”

Serving the Grassroots

Argüello came to PSR–LA “to change the narrative about pesticides,” she said. In the course of her work, she contributed to a coalition of 175 organizations that successfully pushed for new legislation to regulate pesticides in California. However, she said, while the initial efforts of the coalition [Californians for Pesticide Reform] got some attention, it became clear that in order to be successful, their efforts needed to address the issues faced by the people most affected by pesticides: farmworkers, residents of California’s Central Valley, and women and children. PSR–LA and other members, transformed the coalition and eventually became more effective in building grassroots support for this issue, which in turn led to it gaining traction with policy makers.

These changes in leadership and the subsequent expansion of its coalition changed the coalition and in many ways transformed PSR–LA, Argüello said. It was PSR–LA’s work with the coalition that led to the development of PSR–LA environmental health programs addressing air quality, land use, and toxic chemicals. Because it is a small organization, it multiplies its impacts by creating strong coalitions that create bridges between grassroots, policy, and advocacy groups. Coalition building has made it possible to challenge some large adversaries, including the oil industry, makers of flame retardants, and agricultural companies. As its name implies, PSR–LA also represents physicians. “My purpose in life is to unite the powerful voice of communities with a credible voice of health care professionals,” Argüello said. “That can really create a movement for change.” She also emphasized the need to work from the bottom up to craft policy.

____________

5 See http://www.psr-la.org (accessed June 13, 2014).

From Networks to Movements

Recognizing how a single issue can transform a network of groups into a coalition is key to understanding movement building, Argüello said. For example, the health effects of pesticides interested groups that were advocating for tenants’ rights (including the right to inhabit a building not treated with toxic pesticides). This led to the creation of a program (Healthy Homes and integrated pest management pilot) that trained hundreds of promotores and tenant organizers in integrated pest management and is bringing new urban voices to the pesticide reform movement. In another example, she stressed the value of unusual allies. The ability to bridge different movements has proved critical to progress toward stricter safety regulations in California for flame retardants, she said. By talking about the impacts of these chemicals on women, a coalition of affected groups was created that has been effective in changing flammability standards to promote toxic-free fire safety The same networks are now being activated to take on the issue of air quality and its effects on birth outcomes and reproductive health.

“We have to be nimble,” Argüello said of PSR–LA. “We have to be brave and not worry about pushing at the limits of our mission.” Instead, the mission is fluid and often defined or refined as a result of relationships with groups working on issues such as social justice or equity. For example, when residents in south Los Angeles discovered a lead hazard site in their midst, they knew from prior experience to contact Argüello, who was able to provide expert help to the community. Those informed and engaged residents, she said, are “really good organizers.” Although PSR–LA does not usually work on soil contamination issues, their network of relationships with, science, policy, and community organizing groups, called on them to help support local efforts to demand clean-up and redevelopment of the site.

Much as community organizers’ work is often invisible, so is that of organizations such as PSR–LA, Argüello said; both, however, are key agents of change and should be valued as such. Institutions such as the IOM could support community organizers and those they serve by making their research more accessible and by communicating its significance to community health, she added. “We’re always looking to the horizon [for] the next emerging issue” that PSR–LA’s partner organizations will raise and to which PSR–LA will bring its expertise in health, coalition building, and policy development.

A PERSPECTIVE AT THE INTERSECTION OF MOVEMENT AND POLITICS

Gregory T. Angelo, executive director of the Log Cabin Republicans, set out to describe to the workshop “that moment when movements become partisan.” To establish the context, he provided a brief history of his organization, which was founded in 1977 by a group of gay Republicans in California who backed Governor Ronald Reagan during his campaign for President of the United States. They were inspired to organize on Reagan’s behalf due to his opposition to a voter initiative that—had it been upheld by referendum—would have made it illegal for openly gay individuals to be teachers in California public schools. Instead of passing as expected, the proposition failed by a two-to-one margin, a shift that has been attributed to Reagan’s influence. To pay homage to the history of the Republican Party’s longstanding support for civil rights, the group chose a name associated with the party’s first president, Abraham Lincoln.

The Log Cabin Republicans have since federated and are headquartered in Washington, DC, with 39 chapters in 24 states. As a 501(c)(4) organization,6 it engages Republicans on issues of lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender (LGBT) equality and advocates for other issues from a conservative perspective, including the repeal of the ACA—a position not supported by other gay and lesbian organizations. Log Cabin Republicans also has a 501(c)(3) sister organization, the Liberty Education Forum, which is not involved in explicitly partisan activities, but which promotes gay acceptance by conservatives and people of faith. “We’re able to advocate and really educate on those issues while we are advocating and lobbying Republicans in Washington,” Angelo said, “so the two [organizations] work in complementary fashion.”

The Partisan Moment

Prior to leading the national organization, Angelo chaired its New York State chapter, and he was there when, for the first time in U.S. history, a Republican-controlled legislature passed civil marriage equality legislation. This victory followed the defeat of similar legislation under a Democratic administration and legislature, which occurred in part, Angelo said, because advocates of the issue did not communicate with

____________

6 The federal tax code designates tax-exempt nonprofit organizations as either 501(c)(3) or 501(c)(4). The former are public charities, private foundations, or private operating foundations with open membership, while the latter are civic leagues or associations operated exclusively for the promotion of social welfare or local associations of employees with limited membership. See http://www.nj.com/helpinghands/nonprofitknowhow/index.ssf/2008/07/the_difference_between_501c3_a.html (accessed June 13, 2014).

each other. The then newly elected Governor Andrew Cuomo supported an umbrella organization which included the Log Cabin Republicans as its only partisan member. The group was part of that coalition, he said, “because even the liberal advocates, even the advocates who were nonpartisan, understood that there’s a moment when movements like the marriage equality movement become political—that if you want to achieve change . . . you need to get Republicans on board.” The best way to do that, he said, “is to make sure you’re engaging with Republicans who can speak the language of other Republicans who can engage with them on those issues.”

Internal and External Challenges

Some of the toughest challenges faced by the Log Cabin Republicans come from within the organization, Angelo said. “The reason gay Republicans exist is because gay individuals, LGBT individuals, are just that,” he said. They have different opinions and priorities with regard to a variety of issues, including those that have little to do with sexual preference. Anytime the organization takes a specific policy stance, it inevitably excludes a portion of its membership, he reported; however, he was confident that its membership would stand the test of time, as long as the members are satisfied with the balance of the policy positions and see them as consistent with the organization’s mission.

With regard to coalitions, Angelo said, “It’s not just like everyone gets under the umbrella [saying], ‘We’re going to go and achieve change, and all we need to do is just agree on everything.’ . . . Grassroots is unified in the organizing, and policy positions are unified, [but] at the end of the day, no one organization ultimately gets to—or should—claim credit for any legislative victory, because you’re doing it as coalitions.” This situation makes it hard to get foundation funding and satisfy donors, he said. “I don’t think it’s any mistake that after the Marriage Equality Law passed in New York State . . . everyone [in the coalition that supported the law] went their separate ways.” After all, their mission was accomplished, and the coalition partners needed to assert their independence in order to continue operating.

In conclusion, Angelo said that while he considers his job to be one of the most frustrating in the world, it is also sometimes the most thrilling. “Just in the past year that I’ve been head of Log Cabin Republicans, we have had three sitting United States Republican senators announce support for civil marriage quality,” he said. “We had 10 Republicans in the United States Senate vote for the Employment Nondiscrimination Act. We’ve had over 250 Republicans around the country vote for civil marriage equality for committed same-sex couples. And just this afternoon,

. . . Speaker [of the House of Representatives John] Boehner said that Republicans should support openly gay Republicans who are running for the United States Congress.” These are the moments that make his work worthwhile, he said.

George Isham asked Feng about the role of health in the “wheel of promise” framework for MPN (shown in Figure 5-1). She replied that MEDA has constructed several versions of that diagram to highlight different components of its overall strategy for a healthy community. “We’ve actually taken out the academic achievement and put health or housing or something else in there,” she said. This version was prepared to support MEDA’s application for funding by the U.S. Department of Education, which required specific indicators for health, such as the medical home, mental health services, and nutrition and exercise—guidelines that MEDA has exceeded, she added. “Over the next 5 years, the intent is to move those health indicators, along with all the other indicators [in the framework], so that we really do see changes in our families and children in the Mission.”

In response to a request from Terry Allan, Schrantz described two key ways in which community organizing is poorly done. The first she described as “a tactical transactional way of doing quick, shortcut mobilization.” This tends to happen during electoral work or national campaigns when staff is “parachuted” into an area, then leaves without having benefited the community—a practice that can erode residents’ confidence in the potential usefulness of politics or agency, she observed. Second, she said that a lot of organizing is too poorly resourced to be effective; often such efforts, uninformed by careful political analysis, lack a long-term agenda and mismanage important relationships. “The field of community organizing is in a state of great change over the last 15 years,” she added. “There has been a lot of reflection, evaluation and experiments in trying to get to scale, struggling with narrative and message.”

Allan also remarked on the challenge of finding language to make a strong case for health equity across political party lines and on the similarity of that challenge to the one presented by marriage equality. Would Angelo recommend similar tactics, he asked. How can we convey the issue of health equity without making it partisan?

To communicate with Republicans, the term “equity” is probably counterproductive, Angelo said, because it sounds like “something that comes from the progressive dictionary.” Instead, he urged a focus on “equal access” to health care—much as the Log Cabin Republicans framed the issue of marriage equity—and on empowering individuals

and on freedom. “Those are words that resonate across the board with Republicans,” he said. However, he added, one cannot just perform a “find and replace” in one’s documents “in order to create the dossier for Republicans and expect them to entirely get on board. I think you need to find particular policy positions and think about them and . . . engage with Republicans who do health care advocacy.”

Karen Anderson, an IOM staff member, noted that both ISAIAH and the Log Cabin Republicans do “movement work within movements”—promoting social justice within the faith community for the one, and promoting LGBT issues within the Republican Party for the other. What, she asked, are the challenges of doing that sort of organizing?

Schrantz replied that her work and the challenges it presents differ considerably from that of Angelo, in part because the “faith community” is composed of many institutions with varied connections rather than a single political party. This in itself leads to challenges, such as the common assumption that everyone in faith communities regards the relationship between religion and politics in the same way—a polarizing and partisan concept. Thus, she said, “a lot of our work is about deconstructing some of those categories and compartments that people have in their minds and helping people and congregations and communities of faith re-imagine that they can define their own voice and their own role and can contest in the public arena for what it means to be a person of faith in America.”

“My biggest challenge,” Angelo answered, “is constantly having to answer the question, ‘Why are you a Republican?’ I’m only being half glib about that because it opens up the broader question as to why does Log Cabin Republicans exist in the first place. And that’s why I’m always very fond of telling the story of our history to remind people . . . that the Republican Party, at its core, is a party that has placed equality for all Americans at the fore.”