1

The Need for STEM and Management Graduate Education in the Department of Defense

TECHNOLOGY AND MILITARY OPERATIONS

The U.S. military is arguably the most intensely technological, complex enterprise in existence. When compared to the gross domestic products of other countries, the Department of Defense (DoD) budget ranks above all but about 20 nations. If viewed as a company, it would be the largest globally with the most employees. Major investments in weapons systems using advanced technologies provide an advantage over competing systems. Each weapon, platform, vehicle, and person in an operating force is a node in one or more advanced networks that provide the ability to rapidly form a coherent force from a large number of broadly distributed elements. DoD’s ability to create and operate forces of this nature demands a competent understanding by its workforce of the composition, acquisition, and employment of its technology-enabled forces.

Military strategy, concepts, and tactics are greatly affected by particular technological capabilities available to the United States, its allies, and its adversaries. It is important that those who formulate, establish, and use these strategies, concepts, and tactics are capable of understanding the essential combination of technologies, weapons effects, and force dynamics that affect the nation’s security. As an historical example, the advent of nuclear weapons and long-range missiles changed the nature of post-World War II (WWII) conflict and the adversary’s military strategies. The United States responded to the change by placing greater emphasis on developing a more technologically advanced military corps. In retrospect, this emphasis played an essential role in the success of that era, producing a superior U.S.

technology base and a world-class science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and management (STEM+M) DoD workforce and industrial base.

The need to counter, deceive, and cope with adversary forces of competing technological characteristics is an essential part of the military equation. As a consequence, the intelligence function, which has seen significant technological advancement over the past few decades, provides the United States with a capability unmatched in the world today. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance systems of adversaries, as well as our own, is key to deterring conflict and prevailing if deterrence fails. Success depends on sufficient understanding of the differences in capabilities, which, in turn, requires a deeper understanding of all capabilities. This deeper understanding requires a workforce competence and confidence that come only from broadly supported and readily available advanced education in STEM+M subjects.

For example, electronic warfare drives the struggle to dominate the signals environment. Understanding the technical details of electronic warfare is critical to understanding the nature of potential conflicts and using electronic warfare techniques to avoid or win conflicts. The technical breadth and depth of modern electronic warfare systems demands a DoD workforce with advanced technical understanding, largely achieved through graduate-level education and hands-on experience.

A second example requiring a DoD workforce competence in STEM+M is keeping pace with the performance, reliability, and survivability demands on networks, which form the basis of a coherent military force. Cyber operations require a deep technical understanding of the science and art of communications, storage, processing, network security, and the many forms of offensive and defensive actions. A highly skilled workforce capable of effectively designing, implementing, and managing this rapidly evolving domain is critical to modern military operations. Many of the required technical and management skill sets are best obtained through a strong mix of STEM+M programs in which graduate education is a fundamental keystone.

MANAGING THE DEFENSE INDUSTRIAL BASE

DoD acquires nearly all of its military combat systems from the private sector, where the collective defense industrial base performs most of the research, development, design, and production activities. However, the Armed Services and other DoD technical agencies are responsible for conceptualizing, specifying, contracting, testing, and accepting contractor-developed systems before military

use.1 The success of this approach requires competent contractors and a competent government buying entity that understands what it’s buying and how what it’s buying fits into the strategies and operational concepts governing its use. In all likelihood, the context within which a new system is used will differ from the context under which it was initially acquired. This requires that a growing fraction of the military and civilian workforce of DoD have access to relevant advanced STEM+M education in order to bring these two contexts closer and to effectively adapt to the inevitable differences.

Many private sector enterprises in DoD’s industrial base have fewer business dealings with any entity other than DoD. As the overwhelming majority market for these businesses, DoD bears a major responsibility for maintaining the health of its industrial base. The ability to assess DoD’s options for influencing its industrial base requires a sophisticated understanding of advanced technologies and industrial management, typically obtained through graduate education.

In addition to the need for in-house competence to specify and manage the acquisition of knowledge, technology, and systems from the private sector, there are special circumstances requiring government capabilities that advance knowledge, create technologies, and select system designs in an environment of secrecy, security classification, and selective need-to-know under the control of DoD in-house organizations. In particular, the constrained access required for many secure research projects makes it extremely desirable that DoD perform all phases of knowledge and technology creation within DoD technical education and laboratory institutions. Moreover, because the lives of military personnel are ultimately dependent on the ability of DoD personnel staffing these organizations to keep pace with continuously advancing weapon system technologies, they must periodically refresh their knowledge base through graduate education experiences. Chapter 2 provides an overview of DoD-funded and civilian institution graduate education sources.

The current superiority of U.S. military forces is widely recognized as the result of the application of advanced technologies to military systems and operations for the past 50 years or more, together with a global dominance by the U.S. economy in the same time frame.

Finding 1-1. Looking forward to the next 50 years of greater leveling among the global economies and uncertainty about DoD budgets, the elements of superiority must be achieved in other ways. First among them is the need for a more, not

_________________

1 Tim Coffey, Chance Favors Only the Prepared Mind: The Proper Role for U.S. Department of Defense Science and Engineering Workforce, National Defense University, Washington, D.C., August 2013.

the same or less, capable DoD workforce. This is likely to rest on individuals with greater knowledge, experience, and insight in STEM+M areas. This will be true for both military and civilian elements of DoD’s workforce, as well as its industrial base. Relevant graduate education and a culture of lifelong learning are means to those ends.

Recommendation 1-1. The Department of Defense should increase its investments in graduate STEM+M education, even as the total workforce decreases in an increasingly constrained budget environment.

Today and for the foreseeable future, nation-states and non-state actors will challenge the United States with systems built from inexpensive, yet highly disruptive, commercially available technologies, such as the Digital Radio Frequency Memory.2 The U.S. military will not overcome these challenges with large commitments of new resources, as was often the case in the past. Solutions will require a nimble and innovative DoD workforce capable of rapidly and creatively responding to the pace of technical change, which many believe is increasing exponentially with the proliferation of networks and inexpensive, yet highly capable, digital technologies.3 Because trends indicate that future weapon and support systems will increasingly rely on complex technologies, military leaders will likely encounter situations where a basic understanding of technical principles is required to make quality performance, cost, and schedule decisions. Therefore, future military leaders, not just those with STEM+M degrees, would be well served to possess a basic familiarity with technical concepts.

This position is underscored by the recent decision of former Secretary of the Air Force James Roche and Chief of Staff General John Jumper to increase the Air Force leadership’s literacy in and appreciation for STEM. Key Air Force leaders, including the Air Force Secretary, engaged airmen at all levels to emphasize that STEM literacy was a core competency of the Air Force. Going forward, DoD may wish to follow the Air Force example by promulgating a policy requiring military officers and non-commissioned officers to incorporate a basic technology literacy and technology management course in all degree-granting programs funded by DoD. As part of the policy, education monitors and supervisors responsible for reviewing and approving education funding requests would be held responsible for ensuring that those receiving education funds are properly counseled on the

_________________

2 For additional information, see S.J. Roome, Digital radio frequency memory, Electronics and Communication Engineering Journal 2(4):147-153, http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=101420.

3 Ray Kurzweil, The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence, Viking, New York, 1999, pp. 30 and 32.

policy and comply with it. Additionally, a waiver policy could be implemented for employees with truly unique circumstances where the cost of technology-related courses would yield little benefit to the individual or DoD.

Finding 1-2. The use of innovative technology solutions to address enduring DoD problems will not come simply by increasing the number of graduate degrees in STEM+M fields. Rather, it will require greater STEM+M “literacy” by all elements of the DoD workforce.

Recommendation 1-2. The Department of Defense should encourage greater inclusion of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and technically oriented management elements in all education programs in order to deepen the overall STEM literacy of the workforce.

Finding 1-3. The Air Force recently added STEM-related skills as an institutional competency for all military members and civilian employees. 4

Recommendation 1-3. The Air Force’s policy of instilling science, technology, engineering, and mathematics-related skills is one model the Department of Defense should emulate to further institutional competency for all military members and civilian employees.

DoD has a history of cost overruns, excessively long schedules, and performance shortfalls for complex programs that depend on high-technology goods and services. Improving in these areas requires management skills, as well as STEM+M literacy. Thus, leaders with advanced degrees in STEM+M are needed to achieve DoD’s mission within the desired cost, schedule, and performance constraints. The proliferation of failed DoD programs and initiatives highlights the importance of

_________________

4Air Force institutional competencies are defined as the basic and essential knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed throughout one’s career to operate successfully in a constantly changing environment. These education, training, and experiences provide the foundation upon which the Air Force’s lifelong continuum of learning is built. The major categories are “Organizational” (employing military capabilities, enterprise leadership, managing organizations and resources, and strategic thinking), “People/Team” (leading people and fostering collaborative relationships), and “Personal” (embodies airman culture and communicating). Within the “employing military capabilities,” competency is the “leverage technology” sub-competency that addresses STEM related behaviors. Institutional competencies apply to all members of the Air Force, military and civilian, and at all grades by proficiency levels. See U.S. Air Force, Air Force Doctrine Document 1-1: Leadership and Force Development, AFDD1-1, November 8, 2011, http://www.e-publishing.af.mil/.

astute management and leadership. DoD recognizes this need and places emphasis on identifying leaders with potential to make quality decisions and providing them with a broad range of training and educational opportunities, many of which lead DoD professionals to obtain a Master of Business Administration (M.B.A.) degree. The M.B.A. degree is popular among DoD military and civilian employees for several reasons. Employees recognize the importance of management skills and an understanding of how enterprises are managed across the spectrum of business sectors. The M.B.A. is popular in the civilian business world that interacts daily with DoD. The degree carries public credibility that is both attractive and useful. M.B.A. programs offer practical ways to obtain a graduate education while employed full-time. Many of these programs do not require a thesis. And unlike technical degrees, which generally require prior domain knowledge, M.B.A. programs require the type of skills and judgment often developed in the normal course of doing business. An M.B.A. provides value to the employee and DoD and is more accessible to many in the workforce than degrees demanding more technical depth. It is in DoD’s interest to continue encouraging interested employees to seek M.B.A.s when technical graduate education is either impractical or irrelevant for DoD’s and the individual’s needs.5

The Defense Science Board (DSB) published a recent report that stated:

The projected global technology landscape indicates that the U.S. should not plan to rely on unquestioned technical leadership in all fields…Future adversaries may be able to use [information on past asymmetric approaches] along with globally available technology to counter longstanding U.S. advantages and may, in isolated niches, be able to achieve capability superiority.6

These observations led the DSB to recommend that DoD continuously scan the technology horizon and establish a robust experimentation program to create and avoid surprise. The success of both recommendations depends heavily on increased competence in STEM+M areas.

A 2012 NRC report on DoD STEM needs identified rapidly evolving areas of science and engineering with a potential for high impact on future DoD opera-

_________________

5 Caution should be given against treating M.B.A.s, or even graduate degrees in technical fields, as a “check-the-box” situation. DoD is better off with civilians and uniform personnel who receive graduate degrees from accredited and recognized institutions.

6 Defense Science Board (DSB), Technology and Innovation Enablers for Superiority in 2030, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, Washington, D.C., October 2013.

tions.7 This includes the areas of biotechnology and nanotechnology, which are areas of educational concern because they have grown rapidly since most current members of the military and civilian workforces received their STEM education. The rapid advances in biological and nanoscale materials science and technology (S&T), together with a growing array of applications, make it clear that militarily relevant capabilities can and will be created in the coming years. These emerging capabilities promise great opportunities for offensive operations but also present great threats to the nation and its forces. Currently, the level of investment in biotechnology and nanoscale materials by DoD beyond S&T is limited. Historically, DoD has had little engagement with the biological sciences except for its medical needs. Therefore, the number of DoD professionals with biological science expertise is low, and a strong internal advocacy for investment and education in this area has not developed. These are but two examples of emerging technologies DoD might leverage to improve its warfighting capabilities. Without the technical skills needed to understand the theory underlying these technologies, DoD employees will be unable to predict their warfighting impact. This level of understanding is primarily obtained through graduate STEM+M education.

WORKFORCE MANAGEMENT COMPETENCE

In 2008, DoD updated its policy governing graduation programs for military members. The revised policy, which represents a significant shift from earlier policies focused on graduate education to achieve specific competencies for anticipated assignments, emphasized the following:

4.2. Graduate education programs shall be established to:

4.2.1. Raise professional and technical competency, and develop the future capabilities of military officers to more effectively perform their required duties and carry out their assigned responsibilities.

4.2.2. Provide developmental incentives for military officers with the ability, dedication, and capacity for professional growth.

4.2.3. Develop or enhance the capacity of the Department of Defense to fulfill a present need, anticipated requirement, or future capability.8

DoD’s updated policy governing graduate education is much broader than the previous policy and reflects not only a growing dependence on advanced educa-

_________________

7 National Research Council (NRC), Assuring the U.S. Department of Defense a Strong Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Workforce, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2012.

8 Department of Defense (DoD), Instruction 1322.10, DoDI 1322.10, April 29, 2008, http://www.dtic.mil/whs/ directives/, p. 2.

tion but also the need for skills to adapt to a more rapidly changing and uncertain future. In order to maintain the technical and management competence necessary to create, maintain, and operate DoD’s systems, each of the Armed Services has developed its own internal processes for establishing how many DoD personnel are needed for a mission and what kind of advanced education they may need. Some of these processes are tied to the immediate need to fill current and anticipated skill shortages and have fairly specific specifications by specialty, degree, and rank. All are likely to be adversely affected by the ups and downs of current budgets as well as the operational tempo of the Service.

Other DoD education initiatives are tied to more general and strategic workforce education goals as called for in the 2008 policy.9 For example, military personnel at both the officer and enlisted levels know their Service regards higher education as an important indicator for promotion. While not a requirement, a degree can be a key peer discriminator. A cadre of military officers are selected each year by the Air Force, Navy, and Marines to pursue graduate education at either civilian or DoD in-house universities. Others take advantage of DoD’s military tuition assistance to advance their education in parallel with their full-time assignment. Still others pursue additional education and advanced degrees completely on their own time and with their own resources. The choice of institutions, as well as educational content, varies greatly as a consequence of these different initiatives and individual goals.

Finding 1-4. Tuition assistance should be equally important for the military and civilian workforces. But civilian workforce tuition assistance appears to be viewed by DoD as less important and is therefore poorly funded.

Recommendation 1-4. DoD should fund the civilian tuition assistance program at levels similar to the military program in terms of per capita outlay, factoring in an appropriate reduction for the fact that DoD can hire civilians with graduate degrees, whereas military members generally must earn their degrees after joining.

Science, Mathematics, and Research for Transformation (SMART) is a scholarship-for-service program designed to produce the next generation of civilian S&T leaders. Since 2005, the SMART program has helped to educate an average of nearly 100 STEM professionals each year. Roughly 30 percent of SMART scholarships are at the Ph.D. level, while 70 percent are at the master’s level. Participation after 2009 appears to be limited more by budget than by either demand or opportunity. A scholarship recipient typically incurs a 3-year service obligation for each year of release time for education. Smaller but similar “home grown” STEM

_________________

9 DoD, Instruction 1322.10, April 29, 2008.

graduate education programs can be found in many organizations throughout DoD, particularly at DoD laboratories. Although these numbers are not large in the overall workforce context, they are strategically important because they provide a substantial talent pool for securing DoD’s future.

DoD’s various military and civilian education programs have produced a current workforce with the education levels shown in Table 1-1. The committee’s terms of reference (Appendix A) calls for a breakdown of the number of STEM+M degrees “needed by discipline.” Other than the needs identified and funded by the Services’ centralized offices for managing the graduate education of their military officers, the committee was unable to obtain needed data on the entire workforce broken down by STEM+M discipline, or, as Table 1-1 implies, holders of current graduate STEM+M versus other degrees. Creative attempts to deduce or infer current or needed STEM+M degrees in total or by discipline across the workforce resulted in unacceptable levels of uncertainty for drawing meaningful observations, much less actionable recommendations.

Finding 1-5. The Air Force, Navy, and Marines have a comprehensive and well-executed process for the career development of their military officers. Moreover, these Services track and support the graduate education of its officers quite well. The committee reviewed these processes and believes they provide a solid basis for tracking the evolution of the military workforce. The committee had inadequate information to reach a conclusion about the Army processes.

Recommendation 1-5. The expanding global knowledge base and increasing technological complexities of modern military systems and operations suggest the need

TABLE 1-1 Current Department of Defense (DoD) Workforce Broken Down by Degree Level and Major DoD Organization for Military and Civilian Employees

| Doctorate | Masters | Bachelors | Total | |

| Army | 10,720 | 24,585 | 48,119 | 83,424 |

| Navy | 2,884 | 15,830 | 15,259 | 33,973 |

| Marine Corps | 325 | 3,047 | 14,845 | 18,217 |

| Air Force | 7,601 | 31,429 | 22,855 | 61,885 |

| Civilian agencies | 11,904 | 94,486 | 182,341 | 288,731 |

| Total | 33,434 | 169,377 | 283,419 | 486,230 |

NOTE: A detailed analysis was not done to determine the correctness of the outcomes in Table 1-1. These outcomes are embedded in a much larger context of strategic, financial, and personnel decisions made by each institution in support of its workforce needs.

No attempt was made by the source of this data to break out degrees related only to STEM+M disciplines.

SOURCE: Office of the Secretary of Defense (Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics), Washington, D.C.

for a sustained and increased number of graduate STEM+M degree recipients in the future, even if the total workforce decreases. This expansion should be sourced by a combination of DoD-funded graduate schools and civilian institutions (both public and private).

The U.S. military, especially the Army and its Air Corps, undertook a significant training and education effort between WWI and WWII that prepared midgrade officer corps during a period when promotions and operations were limited. This enabled leadership to more rapidly adapt to the mobilization and leadership challenges at the outset of WWII. Such a need and opportunity may lie ahead for the broader DoD.

Growing demands within the civilian element of DoD’s workforce for STEM expertise are evident from recent hiring trends. Comparing 2012 hires to those in 2000 reveals that while the total number of civilians hired is down (31,336 to 29,731), both the number and the STEM ascensions as a fraction of all employees are up: 1,780 to 2,483 individuals, and 5.6 percent to 8.3 percent.10 This trend is significant and consistent with views taken in a pair of earlier NRC reports and a recent forecast by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology that predicts the U.S. workforce will require approximately 1 million more STEM graduates in the next decade than the current pipeline is likely to produce.11,12,13 There are some counterarguments on the future demand for actual STEM jobs in the U.S. civilian workforce; however, the vectors for STEM+M degrees and for competency in these fields are clearly heading up.14 Both the military and civilian components of DoD’s workforce must keep pace with these education and hiring trends if they intend to compete with the private sector for their share of the highest-quality graduates. Although the tracking of civilian graduate education needs and degrees are rudimentary at present (e.g., degree levels only, not degree

_________________

10 Laura Stubbs (Senior Executive Service), Director, S&T Initiatives and STEM Development Office, OASD(R&E)/Research Directorate, “SMART 101,” presentation to the committee on November 8, 2013. Based on DoD S&E occupations under the STEM taxonomy. The subject of a standardized taxonomy/ontology was addressed in the 2012 NRC report. Recommendation 3-2a from that report, which is provided in Appendix D, deals specifically with the need for a standardized DoD taxonomy.

11 NRC, Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2007.

12 NRC, Rising Above the Gathering Storm Revisited: Rapidly Approaching Category 5, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2010.

13 Executive Office of the President, Report to the President: Engage to Excel: Producing One Million Additional College Graduates with Degrees in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, Washington, D.C., February 2012, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/pcast-executive-report-final_2-13-12.pdf.

14 Ibid.

fields), the framework is now available to better track special expertise and degrees by field.

Finding 1-6. A strategic mechanism to track and manage the overall civilian workforce is emerging in the inaugural DoD Fiscal Years 2013-2018 Strategic Workforce Plan Report.15 It appears to be a comprehensive effort to manage the civilian workforce.16

Military and civilian workforces in DoD are constituted in very different ways. For example, unlike the civilian workforce, which can hire a senior Ph.D. scientist off the street, the military workforce is built only at the entry level. Thus, individual career development is the only mechanism to grow military workforce skills and experiences. In contrast, the civilian workforce evolves at all levels and competes in a larger marketplace for its members at all levels.

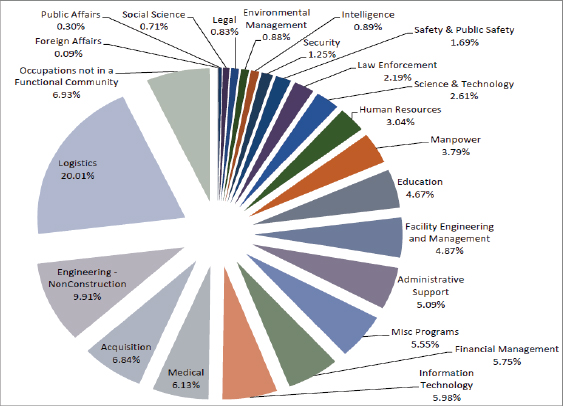

DoD’s civilian workforce is divided into 22 “functional communities” that comprise 93 percent of the civilian population, as shown in Figure 1-1 from DoD’s Strategic Workforce Plan.17 It is estimated that STEM positions can be found in 10 of these functional communities, representing up to 44 percent of the total DoD civilian workforce. This number may be somewhat misleading given that skills and experiences of civilian science and engineering (S&E) personnel assigned the same civil service label vary between and within functional communities. For example, there are about 130,000 DoD S&E employees. One-third of them work in DoD laboratories. The remaining two-thirds mostly work in the major range and test facilities, operational test facilities, logistics and maintenance centers, and system acquisition centers. The skill sets, experiences, and graduate education needs of these employees are quite different, despite the fact they are classified with overlap-

_________________

15 DoD, Fiscal Years 2013-2018 Strategic Workforce Plan Report, Fall 2013, http://dcips.dtic.mil/documents.html.

16 From DoD, Fiscal Years 2013-2018 Strategic Workforce Plan Report (2013):

The plan incorporates the requirements of section 115b of title 10, United States Code (U.S.C.) and builds on lessons learned from previous efforts, which provide a unified process for workforce planning across the Department. The workforce planning process is guided by DOD Instruction (DODI) 1400.25, Volume 250, DOD Civilian Personnel Management System: Volume 250, Civilian Strategic Human Capital Planning, November18, 2008. This DODI establishes DOD policy to create a structured, competency-based human capital planning approach to the civilian workforce’s readiness (p. ii).

[It responds to] Section 935 of the NDAA FY 2012 amended section 115b of title 10, U.S.C. as follows:

• Biennial Plan Required: The Secretary of Defense shall submit to the congressional defense committees in every even-numbered year a strategic workforce plan to shape and improve the civilian employee workforce of the Department of Defense; and

• An assessment of the critical skills and competencies of the existing civilian employee workforce of the Department and projected trends for five years out (vice seven years) in that workforce based on expected losses due to retirement and other attrition (p. 12).

17 DoD, Fiscal Years 2013-2018 Strategic Workforce Plan Report, 2013.

FIGURE 1-1 The Department of Defense (DoD) civilian workforce is divided into 22 “functional communities” that comprise 93 percent of the civilian population in 2012.

SOURCE: DoD, Fiscal Years 2013-2018 Strategic Workforce Plan Report, http://dcips.dtic.mil/documents.html, Fall 2013.

ping labels of the Civil Service System and may be grouped within the same DoD Strategic Workforce Plan functional area.

The need for a more detailed taxonomy within the S&T functional community was identified by a community report (Appendix 7 of DoD’s Strategic Workforce Plan18) and would likely lead to better information on expertise and degree fields for the workforce. To illustrate the point, an S&E employee in a DoD laboratory might choose to cross-train into an acquisition career field while retaining the same Civil Service job series designation and possibly the same functional community. Civilian workforce managers have many marketplaces to use in order to make such transitions within a given billet count and overall workforce. Moreover, STEM careers tend to be a local matter rather than a department- or Service-wide priority. DoD’s Strategic Workforce Plan offers a framework to have a strategic view

_________________

18 DoD, Fiscal Years 2013-2018 Strategic Workforce Plan Report, 2013.

for DoD for its civilian workforce and a means to achieve it, even if the implementation is largely local. If executed correctly, this action will significantly improve DoD’s visibility into, as well as ability to manage, the graduate education needs of its civilian STEM+M workforce.

The remainder of the report is structured as follows: Chapter 2 provides an overview of current DoD STEM+M graduate education and provides working definitions for the relevant terms used in the report. Chapter 3 provides the value proposition for the two primary DoD institutions offering advanced degrees in STEM+M: AFIT and NPS. Chapter 4 provides a broad discussion on alternative ways to enhance graduate education outcomes. Finally, Chapter 5 consolidates recommendations with the six major themes described in the Summary.