3

Refocusing the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

With authorization from the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974, as amended (JJDPA), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) is the congressionally mandated lead agency for juvenile justice. The current statutory purpose is threefold: “(1) to support State and local programs that prevent juvenile involvement in delinquent behavior; (2) to assist State and local governments in promoting public safety by encouraging accountability for acts of juvenile delinquency; and (3) to assist State and local governments in addressing juvenile crime through the provision of technical assistance, research, training, evaluation, and the dissemination of information on effective programs for combating juvenile delinquency” (P.L. 93-415, 42 U.S.C. §5602). Under this authority, OJJDP has the multiple roles of administering programs; assisting states, localities, and tribal governments; and supporting research. It also has the dual purpose of addressing delinquency prevention as well as juvenile justice system improvements.

OJJDP states that it accomplishes its statutory mandate through the provision of “… national leadership, coordination and resources to prevent and respond to juvenile delinquency and victimization.”1 Ultimately, given the breadth of its purpose, the agency’s ability to accomplish its tasks is largely tied to the resources and collaborative efforts that it can invest in the areas selected as priorities. The resources that are available to OJJDP are its staff and the funding and programs it makes available to grantees. OJJDP can also draw on partnerships with other federal agencies and national organizations (see discussion in Chapter 5).

The JJDPA lays out four core protections of youths with which states must comply to receive OJJDP’s formula and categorical funds for improvements to their juvenile justice systems: deinstitutionalization of status offenders, removal of juveniles from adult jail and lockup, sight and sound separation from adult inmates in institutional settings, and the requirement for addressing disproportionate minority contact (see Box 3-1). As noted in the 2013 National Research Council (NRC) report, these protections reflect developmentally appropriate practices.

For over a decade, appropriations for the agency and its grant programs have declined. In addition, at the direction of Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice, OJJDP has taken on increased responsibilities. The combination of diminishing resources and growing responsibilities has reduced the agency’s ability to support juvenile justice system improvement2 (see further discussion later in this chapter).

_________________

1OJJDP’s mission statement available: http://www.ojjdp.gov/about/missionstatement.html [April 2014].

2In response to a question about OJJDP’s role in the reform efforts that have been occurring throughout the nation, a panel presenting to the committee unanimously stated that the agency has not played a significant role in the system improvements, which have occurred largely through the support and efforts of foundations. (Presentation to the committee by the Advocacy panelists on February 14, 2014. See Appendix A for a list of speakers and interviews.)

BOX 3-1

The JJDPA’s Four Core Protections

- Deinstitutionalization of status offenders: Juveniles who are charged with or who have committed an offense that would not be a crime if committed by an adult and juveniles who are not charged with any offenses are not to be placed in secure detention or secure correctional facilities.

- Juveniles are not to be detained or confined in any institution in which they would have contact with adult inmates. Additionally, correctional staff working with both adult and juvenile offenders in collocated facilities must have been trained and certified to work with juveniles.

- Juveniles are not to be detained or confined in any jail or lockup for adults, except for temporary holds of juveniles who are accused of non–status offenses. These juveniles may be detained for no longer than 6 hours as they are processed, waiting to be released, awaiting transfer to a juvenile facility, or awaiting an initial court appearance. Additionally, juveniles in rural locations may be held for up to 48 hours in jails or lockups for adults as they await their initial court appearance. Juveniles held in adult jails or lockups in both rural and urban areas are not to have sight or sound contact with adult inmates, and any staff working with both adults and juveniles in collocated facilities must have been trained and certified to work with juveniles.

- Disproportionate minority contact: States are required to show that they are implementing juvenile delinquency prevention programs designed to reduce the disproportionate representation of minority youth who come into contact with the juvenile justice system at all levels of processing—without establishing or requiring numerical standards or quotas.

SOURCE: Nuñez-Neto (2008).

This chapter reviews OJJDP’s statutory authority, capacity, and current operations and sets forth a blueprint for refocusing OJJDP’s activities so that it can successfully guide juvenile justice reform based on a developmental approach (see discussion in Chapter 2). The chapter first addresses two ways in which congressional action could significantly enhance OJJDP’s capacity to implement the strategic plan outlined in this report: first, by reauthorizing the agency and thereby reaffirming and strengthening its authority, and second, by approving a budget that gives the agency sufficient resources to carry out its mission, particularly the role envisioned here of facilitating juvenile justice reform and system improvements. The chapter then presents the key components of a strategic plan for OJJDP: enhancing staff capacity and refocusing each of the agency’s programs and activities to adequately support juvenile justice system improvement. Such an agenda will require attention to the agency’s training and technical assistance, grant making, demonstration grants, data collection and research programs, and information dissemination, each of which is reviewed below.

REAUTHORIZING AND STRENGTHENING OJJDP

The 2013 NRC report characterizes “… OJJDP as being in a state of decline both in capacity and stature … OJJDP’s 2002 authorizing legislation (P.L. 107-273) expired in 2007 and 2008, although funding support has continued [under annual appropriation acts]. Numerous efforts to reauthorize the agency have been unsuccessful” (National Research Council, 2013, p. 314). Nonetheless, the juvenile justice field continues to support reauthorization and a renewed leadership role for OJJDP.

Although much of what is recommended in this report can be accomplished under the current statutory framework, reauthorization of the JJDPA would establish a firm foundation for OJJDP’s role in the transformative work ahead, as well as signaling to the field that the nation has entered the next stage in juvenile justice reform based upon the research and science of adolescent development. The reauthorizing legislation should identify support for

juvenile justice system improvements based on the science of adolescent development and on evidence regarding the effects of justice system interventions. Reauthorization of JJDPA with updated legislative language would send a strong message regarding the need for state, local, and tribal governments to assume greater responsibility for administering a developmentally appropriate juvenile justice system as a condition for federal support. The 2013 NRC report made two broad recommendations regarding the reauthorization of the JJDPA: restoring the authority of the office through reauthorization, appropriations, and funding flexibility, and strengthening the core protections (see Box 3-2). This committee underscores these previous recommendations with additional suggestions to clarify and strengthen the JJDPA. The suggestions are based on findings from the earlier 2013 NRC report, as well as findings presented in this report as noted. A reauthorized JJDPA should

- Require the OJJDP administrator to develop objectives, priorities, and a long-term plan to improve the juvenile justice system in the United States, taking account of scientific knowledge regarding adolescent development and behavior and regarding the effects of delinquency prevention programs and juvenile justice interventions on adolescent behavior and well-being. (See Chapter 2.)

- Require state plans to describe how the plan is supported by, or takes account of, scientific knowledge regarding adolescent development and behavior and regarding the effects of delinquency prevention programs and juvenile justice interventions on adolescent behavior and well-being. (See Chapter 4 on nurturing state leadership.)

- Require State Advisory Groups to include members who have training, experience, or special knowledge concerning adolescent development. (See Chapter 4 on nurturing state leadership.)

- Require State Advisory Groups to have at least two members of families of youths who have been involved in the juvenile justice system and at least two youths who have been involved in the juvenile justice system. (See Chapter 4 on nurturing state leadership and Chapter 5 on family engagement.3)

- Exclude from the definition of “adult inmate” an individual who, at the time of the offense, was younger than the maximum age at which a youth can be held in a juvenile facility under applicable state law and who was committed to the care and custody of a juvenile correctional agency by a court of competent jurisdiction or by operation of applicable state law. (See National Research Council, 2013, pp. 296-297.)

- Modify the “status offense” provision to preclude placement in secure detention facilities or secure correctional facilities of juveniles who have been charged with or committed offenses that would not be punishable if committed by a person of age 21 or older or that would not be punishable by confinement if committed by an adult. (See National Research Council, 2013, pp. 294-296.)

- Modify the “status offense” provision to eliminate the exception for juveniles who have violated a “valid court order” or have been charged with doing so. (See National Research Council, 2013, pp. 294-296.)

When OJJDP is reauthorized, it should be directed, as recommended by the 2013 NRC report, to base its programs and activities on the scientific knowledge regarding adolescent development and the effects of delinquency prevention programs and juvenile justice interventions; to link state plans and training of State Advisory Groups to the accumulating knowledge about adolescent development; to modify the definitions for “status offenses” and for an “adult inmate” so that all adolescents are treated appropriately; and to identify support for developmentally informed juvenile justice system improvement as one of the agency’s responsibilities.

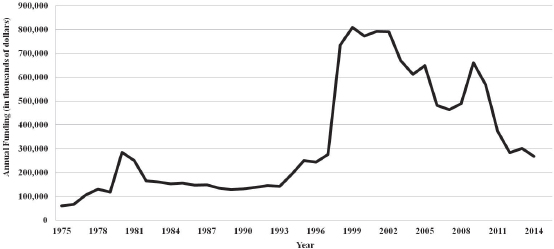

The history of OJJDP’s total funding is shown in Figure 3-1. Since its creation, OJJDP has provided funding through formula grants to participating states and territories to help them meet the goals of the JJDPA and improve

_________________

3Note that the “at least two members of families” requirement is designed to provide for the perspective of legacy families on the SAGs while addressing concerns raised to the committee that a single representative may be perceived as “tokenism” and places too great a burden on one person to represent all families. With two representatives, the commitment to families is underscored and allows for peers to share the responsibility. (Presentation to committee by Family stakeholders on February 13, 2014.)

Recommendation 2: The role of OJJDP in preventing delinquency and supporting juvenile justice improvement should be strengthened.

- OJJDP’s capacity to carry out its core mission should be restored through reauthorization, appropriations, and funding flexibility. Assisting state, local, and tribal jurisdictions to align their juvenile justice systems with evolving knowledge about adolescent development and implementing evidence-based and developmentally informed policies, programs, and practices should be among the agency’s top priorities. Any additional responsibilities and authority conferred on the agency should be amply funded so as not to erode the funds needed to carry out the core mission.

- OJJDP’s legislative mandate to provide core protections should be strengthened through reauthorizing legislation that defines status offenses to include offenses such as possession of alcohol or tobacco that apply only to youths under 21; precludes without exception the detention of youths who commit offenses that would not be punishable by confinement if committed by an adult; modifies the definition of an adult inmate to give states flexibility to keep youths in juvenile facilities until they reach the age of extended juvenile court jurisdiction; and expands the protections to all youths under age 18 in pretrial detention, whether charged in juvenile or in adult courts.

FIGURE 3-1 Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention appropriations in 2014 constant dollars.

SOURCE: Adapted from National Research Council (2013, Figure 10-1, pp. 287) and updated with recent funding totals from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

their juvenile justice systems. These funds, authorized under Title II, Part B, of the JJDPA, can be applied to a wide variety of activities for both delinquency prevention and interventions for youths who come into contact with legal authorities and the system (i.e., justice-involved youths), including but not limited to activities to comply with the core protections (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2014).

Today, OJJDP receives appropriations for a number of programs in addition to its Formula Grants Program for states (see Table 3-1). Within each of these major grant programs, the funding is further subdivided into multiple grant awards and efforts supporting many different program priorities and needs across the country that may (1) address risk factors associated with delinquency; (2) protect missing, exploited, or abused children; (3) prevent and control delinquency; or (4) improve practices and outcomes for system-involved juveniles. A few of the programs are designed specifically to provide training and technical assistance (e.g., those authorized through the Missing Children’s Assistance Act and Victims of Child Abuse Act). The Juvenile Accountability Block Grant (JABG) Program, authorized in 1992, provided funding to OJJDP that could be administered to the states to implement systems of graduated sanctions and other accountability-based programs. “For five years, monies appropriated through JABG represented a significant boost to OJJDP’s budget and, very important, [were] a source of funding states relied on to build and strengthen their juvenile justice system infrastructure” (National Research Council, 2013, p. 286).

TABLE 3-1 OJJDP Funding by Fiscal Year (FY) (thousands of dollars [actual])

| OJJDP Appropriations | FY 2011 | FY 2012 | FY 2013 | FY 2014 | |

| Juvenile Justice Programs | |||||

| Part B-Formula Grants & State TA | 62,126 | 40,000 | 44,000 | 55,500 | |

|

[Emergency Planning Detention Facilities] |

— | — | [500] | [500] | |

| Youth Mentoring | 82,834 | 78,000 | 90,000 | 88,500 | |

| Title V-Local Delinquency Prevention | 53,842 | 20,000 | 20,000 | 15,000 | |

|

Incentive Grants |

[4,141] | [0] | [0] | [0] | |

|

Tribal Youth Program |

[20,709] | [10,000] | [10,000] | [5,000] | |

|

Alcohol Prevention/EUDLa |

[20,709] | [5,000] | [5,000] | [2,500] | |

|

Gang Prevention/OJJDP |

[8,283] | [5,000] | [5,000] | [2,500] | |

|

Juvenile Justice Education Collaboration |

[0] | [0] | [0] | [5,000] | |

| Juvenile Accountability Block Grant | 45,559 | 30,000 | 25,000 | [0] | |

| Missing and Exploited Children | 69,860 | 65,000 | 67,000 | 67,000 | |

| Safe Start | 4,141 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Child Abuse Training for Judicial Personnel | — | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,500 | |

| Improving Investigation & Prosecution of Child Abuse | 18,638 | 18,000 | 19,000 | 19,000 | |

| National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention | — | 2,000 | 2,000 | 1,000 | |

| Children of Incarcerated Parents Web Portal | — | — | — | 500 | |

| Girls in the Justice System | — | — | — | 1,000 | |

| Community-Based Violence Prevention | 8,283 | 8,000 | 11,000 | 5,500 | |

| Subtotal | 345,283 | 262,500 | 279,500 | 254,500 | |

| State and Local Law Enforcement Assistance | |||||

| Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) | 12,425 | 4,500 | 6,000 | 6,000 | |

| Child Abuse Training for Judicial Personnel | 2,071 | — | — | — | |

| Children Exposed to Violence | — | 10,000 | 13,000 | 8,000 | |

| State and Local Subtotal | 14,496 | 14,500 | 19,000 | 14,000 | |

| TOTAL OJJDP: | 359,779 | 277,000 | 298,500 | 268,500 | |

aEUDL is the Enforcing Underage Drinking Laws Program.

SOURCE: Presentation to the committee, Overview of OJJDP’s Mission and Budget, by Robert Listenbee and Janet Chiancone, January 22, 2014.

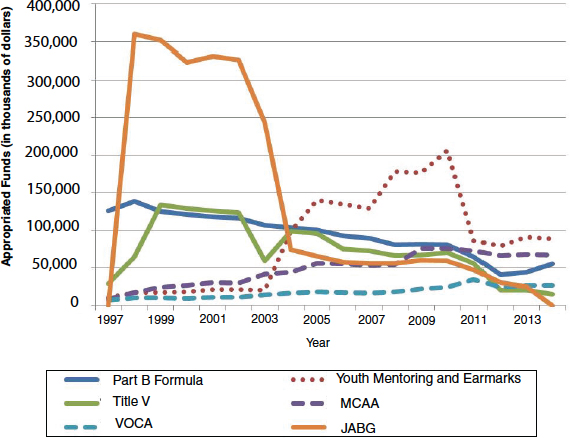

The 2013 NRC report noted that funds to support the Formula Grants Program dropped from two-thirds of OJJDP’s budget in its early years to less than one-fifth of its budget in 2010 and that funding for JABG declined from 1999 to 2010 to one-sixth of its original appropriation (see Figure 3-2). That report articulated how declines in funding for OJJDP’s formula and categorical grant programs reduced the resources that could be provided to states to address their own needs and limited OJJDP’s capacity to influence improvements within juvenile justice systems.

As the number of appropriated carve-outs continued to rise, OJJDP’s portfolio was increasingly shaped by congressional priorities, and its ability to support the agency’s original mission declined…. By 2008, the budget for its combined state formula and block grant programs dropped to one-third of OJJDP’s total budget.

(National Research Council, 2013, pp. 286-287)

… funding available to support juvenile justice improvements by state and local governments… steadily declined by 83 percent from 1999 to 2010 in constant 2010 dollars. The reason for this decline is the dramatic decline in funding available through JABG since 2003 as well as the increase in appropriated carve-outs under Title II and Title V (e.g., Enforcing Underage Drinking, Tribal Youth Program, mentoring) and earmarked programs….

(National Research Council, 2013, pp. 308-309)

FIGURE 3-2 Trends in Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention continuing funding streams in 2014 constant dollars, 1997-2014.

SOURCE: Committee generated, data provided by Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

NOTE: JABG = Juvenile Accountability Block Grant; MCAA = Missing Children Assistance Act; VOCA = Victims of Child Abuse.

The increase in funds directed at mentoring programs comes at a price…. Because funds to support OJJDP’s hallmark state formula and block grants are declining, OJJDP is constrained from helping states and localities with other interventions that may better fit their local needs for preventing delinquency. Mentoring is but one intervention. Research has shown that it takes a succession of effective experiences (or interventions) for adolescents to develop into prosocial adults. No single program can serve all youth or incorporate every feature of positive developmental environments (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2002). Therefore, excessive resources in one program, like mentoring, do a disservice to the juvenile justice field more generally and to state, local, and tribal jurisdictions more specifically by overriding or ignoring their efforts to assess their own identified needs and efforts.

(National Research Council, 2013, pp. 313-314)

Little has changed since 2010. OJJDP continues to be allocated funds and responsibility for programs that are only loosely connected to the juvenile justice system. Most important, as Figure 3-2 shows, OJJDP has a declining pot of discretionary funds that can be directed specifically at juvenile justice system improvement. Formula Grants Program funds have been cut in half since 2005, and the JABG Program, a major source of system improvement funding from 1998 to 2004, was zeroed out in 2014. Even in the area of local grants for delinquency prevention, the total Title V funding is less than a quarter of what it was in 2010. As funding has decreased in most grant program areas, concern has been expressed by juvenile justice practitioners that spreading the funding out to multiple program areas and grantees may have the unintended consequence of reducing the impact that the agency can have in achieving its mission.4

Declining funds in combination with appropriation carve-outs have diminished the flexibility and reach of OJJDP’s research portfolio and its training and technical assistance capacity. The 2002 reauthorization of JJDPA amended Title II to provide authority to the OJJDP administrator to oversee research, evaluation, training, technical assistance, and information dissemination (Title II, Part D).5 However, funds for Part D were only appropriated in fiscal 2004 and 2005 and discontinued thereafter. Thus, OJJDP relies on a small percentage of its categorical and formula grant funds that can be set aside for training and technical assistance and research as related to the respective topic area. The set-asides through Title II funding streams could be directed at system reform and improvements, given the broad nature of the programs. Unfortunately, in recent years much of this funding has been carved out in appropriations for juvenile mentoring projects; therefore, the set-asides for training and technical assistance and research under this carve-out must be applied toward mentoring.6 The committee finds it quite disturbing that appropriations for mentoring programs in 2014 exceeded OJJDP’s total funding for Part B Formula Grants for states and Title V local delinquency prevention. As noted above, mentoring is just one kind of intervention; whereas funding through the Formula Grants Program and Title V local delinquency prevention can be directed toward other types of interventions, which may be more appropriate to reform in a given jurisdiction.

The agency reported to the committee that it takes a two-pronged approach to planning its research agenda (which includes basic research as well as evaluations and statistical data collections).7 First, OJJDP uses set-asides from formula funding to support research directly focused on the juvenile justice system and system-involved youths. Given that appropriations for the Formula Grants Program are declining, the agency has directed available funds toward sustaining some of its core research programs such as field-initiated research and evaluation, statistical data analyses, and its model programs guide. Second, OJJDP supports additional research using the directed program funds; this portfolio focuses on delinquency prevention and victimization, although a small proportion of these projects also relate to justice system issues. With directed funding (see Table 3-1), the agency has been able

_________________

4Presentation to the committee by the Advocacy panelists on February 14, 2014. See Appendix A for a list of speakers and interviews.

5The 2013 NRC report (p. 311) notes “[t]he original JJDPA of 1974 established the National Institute for Justice and Delinquency Prevention (NIJJDP) within OJJDP to conduct research and evaluation, development and review of standards, training, and collection and dissemination of information. A research institute of significant size and stature never materialized…. The 2002 reauthorization of JJDPA amended Title II to eliminate NIJJDP and provide authority directly to the OJJDP administrator to oversee research, training, technical assistance, and information dissemination.”

6Presentation to the committee, Overview of OJJDP’s Mission and Budget, by Robert Listenbee and Janet Chiancone, January 22, 2014. See also H.R. 3547, Omnibus Appropriations Act, 2014, 128 STAT 60.

7Presentation to the committee, Overview of OJJDP’s Training and Technical Assistance and Research, by Brecht Donoghue, January 22, 2014.

to sponsor research on tribal youths, drug courts, mentoring, youth and community-based violence prevention, gangs, underage drinking laws enforcement, missing and exploited children, and children exposed to violence.

OJJDP’s portfolio of training and technical assistance is similar to its research portfolio in that directed funding streams are heavily focused on delinquency prevention and child victimization, as opposed to the juvenile justice system and system-involved youths. However, OJJDP has been able to stretch its limited budget for training and technical assistance across a broad set of issues. The agency reported to the committee that it had 65 different training and technical assistance projects. Most of these are specific to a grant or a program, but some are request driven.8

The committee heard from constituents that they have substantial needs for training and technical assistance that OJJDP is unable to meet.9 OJJDP reports it currently funds training and technical assistance projects at about $50 million per year.10 As noted in the 2013 NRC report, about 80 percent of this is dedicated to programs outside the scope of juvenile justice system improvement (e.g., victims of child abuse and missing and exploited children). Remaining funds are spread across assistance for a broad set of topic areas. The current approach to training or technical assistance is not well suited to deliver the kind of transformation OJJDP is hoping to achieve. It spreads resources in a manner described to the committee as “a mile wide and an inch deep.”11

A key recommendation in the 2013 NRC report was that federal policy makers should restore OJJDP’s capacity to support juvenile justice system improvement through reauthorization, appropriations, and funding flexibility (National Research Council, 2013, p. 328) based upon an analysis of the budget and appropriations that is relevant today:

[N]umerous carve-outs and earmarks have diminished the capacity of OJJDP’s authorized programs—particularly its state formula/block grant programs, mandate to coordinate federal efforts, nonearmarked research and data collection, and technical assistance—to carry out the core requirements of the JJDPA (National Research Council, 2013, p. 308).

To realize greater impact, it may be necessary to further target appropriations on reform of the juvenile justice system and implementation of the hallmarks for that reform (see discussion in Chapter 2). OJJDP currently has authority to provide a range of functions in two statutory domains: delinquency prevention and juvenile justice system improvement. However, its current program portfolio is unbalanced, with the majority of its recent funding resources directed at a single type of intervention: mentoring.

As an approach to building resiliency, mentoring has presented numerous positive effects such as improved academic performance and increased social competence. However, the evidence is less clear about the relationship to delinquency prevention (the agency’s mandated function) or the characteristics of youths that benefit most from mentoring (National Research Council, 2013, p. 432). And yet, OJJDP is required to support mentoring for tribal youths, sexually exploited children, youths with disabilities, and youths in military families, regardless of whether there is evidence for (1) the likelihood of the mentored population engaging in delinquent behavior, (2) any benefit from mentoring for those populations, or (3) any connection to preventing delinquency in those populations (National Research Council, 2013, p. 434).

As illustrated in Figure 3-2 and noted in the 2013 report, “the increase in funds directed at mentoring programs comes at a price… Because funds to support OJJDP’s hallmark state formula and block grants are declining, OJJDP is constrained from helping states with other interventions that may better fit their local needs for preventing delinquency” (National Research Council, 2013, p. 313). Further, as the only federal agency specifically mandated to assist the states in improving their juvenile justice systems (P.L. 93-415, 42 U.S.C. §5601 et seq; also see National Research Council, 2013, p. 281), when the agency’s ability to support systemic activities is reduced there are few, if any, alternative sources of assistance. The committee envisions a rebalancing of OJJDP’s appropriations to reflect

_________________

8Ibid.

9Presentation to the committee by the Legal panelists on February 13, 2014. See Appendix A for a list of speakers and interviews.

10Presentation to the committee, Overview of OJJDP’s Training and Technical Assistance and Research, by Brecht Donoghue, January 22, 2014.

11Presentation to the committee by the Advocacy panelists on February 14, 2014. See Appendix A for a list of speakers and interviews.

the full range of OJJDP’s mandated functions and an increase in flexibility to allow the agency to target resources to the specific needs of the states.

Even if the agency is given greater flexibility in using its funding, its current appropriations do not give it adequate capacity to carry out the activities that were envisioned by Congress in enacting the JJDPA or the critical mission articulated in this report. The answer to that problem is for federal policy makers to increase both the amount and proportion of the agency’s appropriation that are available to the agency to carry out its core mission.

Assisting states, localities, and tribal jurisdictions to align their juvenile justice systems and delinquency prevention programs with current best practices and the results of research on adolescent development and implementing developmentally informed policies, programs, and practices should be the agency’s top priority under the JJDPA. Any additional responsibilities and authority conferred on the agency should be amply funded so as not to erode the funds needed to carry out support for system improvement. OJJDP’s ability to effect change in the juvenile justice field in the foreseeable future will be severely constrained without adequate legislative and budgetary support by federal policy makers. The funds available to OJJDP should be ample enough, and sufficiently flexible, to enable the agency to hire, train, and retain the necessary staff and to provide the demonstration grants, research, and technical assistance needed to support developmentally informed justice system improvement and reforms by states, tribes, and localities.

The above discussion has focused on changes in OJJDP’s funding for programs authorized under JJDPA to show that OJJDP has declining discretion and opportunity to support the needs of and provide assistance to states and localities for juvenile justice system improvement, a primary responsibility under the JJDPA. OJJDP currently has the appropriate authorities and tools across a range of function areas through JJDPA to carry out this purpose, but it will at least need greater flexibility in all funding sources within its budget in order to direct resources to systemic reforms, targeted and efficacious programs, and training or technical assistance designed to support states and localities in efforts to reform their juvenile justice systems. The committee emphasizes that it is not saying Congress should not assign OJJDP responsibilities under other statutes. Rather, the committee’s position is that these added duties should be funded adequately on their own and should not be accomplished at the expense of the agency’s capacity to carry out its responsibility for supporting juvenile justice system improvement.

The administrator and executive staff of OJJDP need to present a clear vision and strategy for change within the agency itself, build or expand internal capacity to support the change, and garner external support. In order to facilitate reform within the nation’s diverse juvenile justice system, OJJDP needs to persistently communicate a clear vision and strategy for system reform in state, local, and tribal jurisdictions; prioritize resources for achieving reform; and foster relationships necessary to sustain reform.

To begin to support a developmentally oriented juvenile justice system, OJJDP will need to incorporate the vision of a developmental approach outlined in Chapter 2 into all of its operations, partnerships, and functions (including training and technical assistance, demonstration programs, data collection, research, and information dissemination). In presentations to the committee, the agency reported that all employees have become familiar with the 2013 NRC report and each of the guiding principles (see guiding principles box in Appendix B).12 It is notable that in 2013-2014 the OJJDP administrator and staff have presented at numerous conferences on the importance of a developmental approach. However, more work needs to occur to bring about changes in the organizational culture and to fully integrate the hallmarks of a developmental approach into OJJDP’s grant making and engagement with the juvenile justice field.

In the committee’s view, OJJDP’s main challenge is to align programs, activities, and staff operations with facilitating juvenile justice system improvement, given that available funding (and resulting programs and operations) have leaned heavily toward delinquency prevention. Changing an institution takes time and persistence and

_________________

12Presentation to the committee, Overview of OJJDP’s Mission and Budget, by Robert Listenbee and Janet Chiancone, January 22, 2014.

requires a concerted effort to align the organizational culture with a new vision. Part of this investment is necessary to inspire agency staff to embrace the change. Research has identified the following stages of individuals’ acceptance during an institutional change (Barnard and Stoll, 2010): (1) employees are unaware that change is needed or intended and are operating to maintain the status quo; (2) employees are resistant and/or uninformed because they have yet to understand the rationale for and the scope of the change and how it will affect them; and eventually (3) employees are accepting of and committed to new policies and practices and the new status quo.

For each stage of resistance/acceptance, communication and support during a period of change should be tailored to the extent possible (Wiggins, 2008/2009). To make decisions on such communication and support, leaders and managers implementing the change should have an understanding of existing, as well as changing, structures, personnel, and culture within the organization (Barnard and Stoll, 2010). One strategy for reducing resistance, recognized in the literature, is to involve employees in the discussions and decisions about the process for implementing changes (Denhardt and Denhardt, 1999; Poister and Streib, 1999; Warwick, 1975).

Recent transformation in the organization and priorities of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (from investigation of federal crimes to intelligence and information gathering to prevention of terrorism), following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, provides an example of how a federal agency implements a comprehensive transformation plan—modifying its own policies, priorities, and practices as necessary; hiring or reassigning staff members with appropriate skills and characteristics; and conducting appropriate staff training—to align and build momentum for successful and sustained transformation (U.S. Department of Justice, 2004; U.S. General Accounting Office, 2003). Once embraced by its organizational culture and implemented in policies, procedures, and practices, a clear vision can continue as a guiding philosophy for OJJDP regardless of subsequent leadership changes.

Efforts are needed to support staff development aimed at gaining the knowledge needed to implement OJJDP’s statutory functions so that staff can lead adoption of the desired changes in the juvenile justice system. OJJDP should strive to ensure that each of its divisions is well staffed with trained professionals skilled in the areas needed to guide a strategic reform effort based on a developmental approach. An important step in the agency’s strategic effort to remake itself should be to initiate and sustain an agency-wide training activity designed to inform all professional staff about advances in developmental science and their implications for juvenile justice system improvement. The purpose should be to ensure that all staff become and remain current in their knowledge and skills. There will need to be OJJDP staff skilled in working with appropriate decision makers, researchers, and experienced system improvement practitioners in jurisdictions, to help them understand how to achieve desired outcomes. As discussed earlier, many of these jurisdictions are trying to apply a developmental approach to reform of their systems.

A training curriculum will need to be developed that can provide guidance and best practice approaches to OJJDP staff, training and technical assistance providers, and ultimately the juvenile justice field. The curriculum will need to recognize and incorporate the current science of adolescent development and demonstrate methods for applying best practices at each of the key decision points in the juvenile justice system. This is best accomplished through the creation of an external transition advisory group to work with OJJDP leadership and identified staff as part of a transition or change management team. Through this collaborative approach to curriculum development, the best available knowledge, skills, content, length, and learning styles can be incorporated in the context of OJJDP culture and its training and contracting processes, as well as being disseminated to the range of stakeholders in the juvenile justice field.

The best model for such development can be found in best practices employed by a number of experienced universities and certified training institutes. These practices include but are not limited to a course introduction and map; various learning modules that consist of objectives, content presentations and materials; topic assessment/evaluation; and topic discussion opportunities. The course content should cover topics such as the history of the juvenile court and juvenile justice system, including racial disparities; the history and current statutory authority of OJJDP; the best available research on adolescent development, including the relation between brain development and behavior; the hallmarks of a developmental approach to juvenile justice reform (see Box 3-3 and Chapter 2);

BOX 3-3

Hallmarks of the Developmental Approach to Juvenile Justice

- Accountability Without Criminalization

- Alternatives to Justice System Involvement

- Individualized Response Based on Assessment of Needs and Risks

- Confinement Only When Necessary for Public Safety

- A Genuine Commitment to Fairness

- Sensitivity to Disparate Treatment

- Family Engagement

SOURCE: Committee generated (see Chapter 2).

the key components of system change; and strategic partners with whom OJJDP will work to achieve effective implementation of such reforms (see discussion in Chapter 5).

The examples shown in Box 3-4, which feature two key decision points in the juvenile justice system, begin to demonstrate the opportunities that exist for OJJDP—once it has strengthened its internal capacity—to reform the juvenile justice system through the implementation of training and technical assistance that address key decision makers within the system and present methods to apply science-based knowledge about adolescent behavior. OJJDP staff and the agency need to be positioned to use their knowledge of adolescent development to inform the goals and outcomes for the decision makers in the juvenile justice system. This should be accomplished by first ensuring that OJJDP staff internally achieve an expert understanding of the hallmarks of a developmental approach, the research implications for treatment of youths, and the best approaches for appropriately responding to youths, and then using that knowledge to shape the training and technical assistance OJJDP provides. In addition, OJJDP can consider using the Intergovernmental Personnel Act Mobility Program, which provides for the temporary assignment of personnel between the federal government and state and local governments, colleges and universities, Indian tribal governments, federally funded research and development centers, or other eligible organizations. OJJDP also can enter into interagency agreements for the accomplishment of mutual objectives (see Chapter 5).

Recommendation 3-1: OJJDP should develop a staff training curriculum based on the hallmarks of a developmental approach to juvenile justice reform. With the assistance of a team of external experts, it should implement the training curriculum on an ongoing basis and train, assign, or hire staff to align its capabilities with the skills and expertise needed to carry out a developmentally oriented approach to juvenile justice reform.

MAKING SYSTEM REFORM A PRIORITY

Rethinking Training and Technical Assistance

The OJJDP National Training and Technical Assistance Center has published the Core Performance Standards for Training, Technical Assistance and Evaluation to promote consistency, quality, and effective practice in the planning, coordination, delivery, and evaluation of training and technical assistance. For example, these standards for provision of technical assistance outline all documentation that must be received before responding to a request, provide questions for conducting a needs assessment, provide a checklist for developing a comprehensive technical assistance plan, describe how to select a technical assistance provider that is most likely to be able to deliver appropriate information to the target audience, and outline elements of a comprehensive written final report. Although

BOX 3-4

Training Curriculum Decision Point Examples

The referral/intake decision is almost universally driven by the statutory requirement of determination of legal sufficiency (or probable cause) that a youth committed a codified offense(s). In the majority of jurisdictions across the country, this decision is frequently followed by a routine next step that involves petitioning the court to formally hear the matter. While there have been advances in the use of diversion and other alternative response opportunities created at this decision point, many jurisdictions only consider legal sufficiency before processing a petition and setting the matter for a court hearing.

Upon receipt and establishment of legal sufficiency, Newton County (Georgia) Juvenile Court has inserted a step that includes an intake staffer that considers additional background information from multiple sources (family, relevant other youth-serving agencies, etc.) prior to determining the most appropriate next process step (St. George, 2011). This step is deliberately intended to explore opportunities to incorporate knowledge derived from developmental science into the treatment plan for the adolescent. This may include simply diverting the adolescent back to the community without services if the level of risk for future offending and need for services are low.

A second example involves the pre-disposition decision by the court. On adjudication of a delinquent offense, many jurisdictions routinely consider only the information available to the court at the time of the adjudication. A much smaller percentage of cases is referred to the probation services department for the preparation of a pre-sentence or pre-disposition report. Combining adjudicatory and dispositional proceedings frequently provides limited or no opportunity to incorporate a developmental approach into an effective intervention plan. Forfeiting the opportunity to adequately incorporate sufficient background developmental information (including validated screening and assessment for dynamic risk factors) in a deliberate and comprehensive manner into the report to the court often results in an array of accountability provisions and court orders without the balance of considering potential contributors to the behavior (National Research Council, 2013, pp.139-181). There are many reasons proffered for this practice (time constraints, workforce resources, federal and state laws precluding exchange of information, etc.), but the failure to account for the developmental aspects in routine practice frequently results in technical violations of the court order and unwanted recidivism.

these standards describe the building blocks for understanding technical assistance, they provide little guidance regarding mechanisms and techniques for providing and receiving effective technical assistance.

A clear definition, purpose statement, and vision for technical assistance are needed to use this tool effectively for reform in the states. A valuable set of principles has been compiled in the article, “Providing and Receiving Technical Assistance: Lessons Learned from the Field” (Soler et al., 2013). These lessons reflect important experiences from the technical assistance providers in the MacArthur Foundation’s Models for Change initiative and their relationship with the states and local jurisdictions with whom they partnered over the past decade. Lessons from this engagement could guide OJJDP in developing a new approach to technical assistance provided in support of reform efforts:

- The need for technical assistance should be sharply aligned with the reform goals of the jurisdiction.

- Providers should establish clear boundaries on the technical assistance being provided, as well as an exit strategy.

- Providers of both training and technical assistance should be required to demonstrate mastery of the developmental approach; they must develop capacity not only to deliver a training curriculum but also to understand and be responsive to the needs of states, localities, and tribal jurisdictions in implementing system reforms.

- A written training and technical assistance work plan should have concrete objectives, strategies to be employed, desired outcomes, measures of progress, individuals responsible for each activity, and timelines for completion.

- Jurisdictions and technical assistance providers should collect and analyze data necessary to assess the effectiveness of efforts to provide a solution to the technical assistance request.

- Technical assistance providers should offer concrete examples of other jurisdictions and facilitate interjurisdictional connections.

It is clear from these lessons that system reforms require intensive and sustained engagement. Each juvenile justice system is different, and each has different strengths and weaknesses. Given the unique features of each jurisdiction, the duration and intensity of technical assistance should match the actual need for support to build capacity and achieve objectives.

Long-term, intensive assistance has been arguably absent from the OJJDP approach in recent years. In addition, OJJDP’s reliance on a pay scale for designated technical assistance providers that had not increased since the 1990s has undercut the agency’s ability to partner with many of the best and most knowledgeable juvenile justice experts (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2014).13 Some of the OJJDP-approved providers are not viewed in the field as having expertise in the areas for which they are approved by OJJDP to deliver training and technical assistance. For example, in the area of family engagement, some providers lack staff expertise as a family member of a system-involved youth and have not transparently consulted families impacted by the system (i.e., system-involved families or legacy families) in the development of resource materials.

A notable requirement of the JJDPA is that training and technical assistance partnership grants may be made “only to public and private agencies, organizations, and individuals that have experience in providing such technical assistance” (P.L. 93-415, 42 U.S.C. §5601 (Sec. 221)(b)(2)). OJJDP should strive to identify training and technical assistance providers that have the expertise to meet the needs of states and localities. In this current period of reform, this will require working knowledge of the hallmarks of a developmental approach to reform discussed in Chapter 2. Providers must be receptive to and skilled in analyzing the nuances of a client’s juvenile justice system so that a clear plan can be developed. Execution of that plan needs support as well, so multiyear commitments may be needed. In addition, if the entity requesting technical assistance does not have robust data collection and reporting systems, that deficiency must be addressed as a threshold matter or as part of the first step in establishing the reform effort. Data should be used to establish baselines and track progress (see discussion on administrative data later in this chapter).

While the approaches to technical assistance vary, the lessons from the provision of technical assistance through foundation-led efforts such as the Models for Change initiative and the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative are instructive as OJJDP embarks upon a new and more strategic approach to delivering training and technical assistance. Providers will also need to be able to develop or access learning networks14 to facilitate interjurisdictional connections, sharing of information, and imparting lessons learned. The training curriculum discussed earlier should also be modified to train providers. Such preparation for providers and a framework for providing training and technical assistance to states and localities based on a system improvement model are set forth in greater detail in Chapter 4.

As with many government grant-making agencies, OJJDP has the competing goals of funding innovative and promising programs while remaining vigilant to the risk of waste, fraud, and abuse in awarding and overseeing grants (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009a). OJJDP once enjoyed a reputation for pioneering grant making in partnership with grantees while upholding the highest standards of integrity. That reputation has suffered in recent

_________________

13OJJDP’s pay scale for technical assistance providers was changed in May 2014 (increased to $650 per day).

14“Learning community,” “learning network,” or “community of practice” are terms to describe a group of people who intentionally share information and experiences to learn from each other and to accelerate the learning curve of the members (Wenger et al., 2002).

years, likely due to the pressures resulting from the scrutiny of the agency’s 2007 grant awards combined with a lack of leadership and strategic vision (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009b).

Many in the field see OJJDP as overly focused on grant and compliance monitoring, with staff largely viewed as grant auditors rather than potential partners in reform efforts.15 OJJDP’s role in enforcing compliance with the core protections from the JJDPA appears to consume significant staff resources, despite the fact that compliance rates are in the mid-90th percentiles and the agency has limited ability to bring the few noncompliant states into compliance (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2012). Similarly, the resources spent on monitoring grant activities seem to this committee to be outsized in relation to the gains to the agency, the grantees, or the field.

While it is necessary, of course, to ensure that awarded monies are spent on projected activities and services, the committee is convinced that this function can be served much more efficiently. OJJDP should strive to establish a better balance between grant monitoring and system reform activities by re-examining the monitoring systems to identify ways to ensure compliance that are less resource-intensive. The agency demonstrated this balancing previously, and the possibilities include (1) a random audit of representative samples with in-depth reviews of selected programs, with monitoring focused on outcomes rather than process; (2) a rotating schedule of full reviews with monitoring of remediation plans in the intervening years; or (3) contracting out the monitoring function.

Recommendation 3-2: OJJDP should establish a better balance between grant monitoring and system reform efforts by examining more efficient ways to monitor grants and compliance with the core protections from the JJDPA.

In addition, OJJDP resources have been reduced but the priorities of OJJDP have remained broad, thus spreading resources too thinly across too many activities. OJJDP can restore its reputation for strategic grant making—while still supporting the needs in the field—by concentrating the focus of its grants on the hallmarks of a developmental approach. The committee notes that OJJDP previously achieved this type of balance in its work through the Comprehensive Strategy for Serious, Violent and Chronic Juvenile Offenders (hereafter, the Comprehensive Strategy) and adopting a similar approach would support a developmental focus across the agency’s prevention and intervention activities. OJJDP would also be well served by re-examining many of the tools and resources created in past years such as “cciTools,” which was created for federal agency staff16 and contains useful generic grant-making resources designed to support system reform activities.

Under Sections 261 and 262 of the JJDPA, OJJDP has the authority to develop, in partnership with a select number of states, demonstration or pilot grant programs that could be designed to improve the routine use of the hallmarks of a developmental approach. The JJDPA authorizes OJJDP to support units of local governments and other public and private agencies and organizations to develop, test, and demonstrate promising initiatives and to provide technical assistance to those entities. Extensive, sustained, high-quality technical assistance through partnerships with national organizations will be needed to plan and implement these system reforms. (See Chapter 4 for discussion on training and technical assistance and Chapter 5 for discussion of partnering with national organizations to provide such training and technical assistance.)

OJJDP will need to explore with its federal agency partners ways to blend or leverage available federal, state, and local funds to support these demonstration grants. This could be accomplished by providing greater flexibility in allowable uses of existing federal financing; dedicating a share of, or creating a preference within, an existing federal program; creating exemptions (or waivers) for certain state or federal funding restrictions based on a link to the results sought, such as the state match, program eligibility requirements, or timelines in existing federal programs; and pooling federal funding by bundling several programs under the initiative. (For further discussion

_________________

15Presentation to the committee by the Legal, Advocacy, and State Advisory Group panelists on February 13 and 14, 2014. See Appendix A for a list of speakers and interviews.

16For more information, see http://www.ccitoolsforfeds.org [May 14, 2014].

of leveraging funding streams, see Chapter 5.) In addition, OJJDP will need to explore public/private partnerships with a foundation or consortium of foundations to create flexible funding that can be made available to states, counties, cities, or tribes that are selected to participate in the demonstration. OJJDP’s goal for demonstration grants would be to provide replicable guidance for state, local, and tribal jurisdictions across the country, based upon the documented experiences and achievements of these pilot jurisdictions, while building requirements for reforms into future grant making.

As noted above and in the 2013 NRC report, a signature program of OJJDP that evolved more than a decade ago—the Comprehensive Strategy—is illustrative of OJJDP’s past efforts to support research-based demonstration programs combined with technical assistance efforts that focus on both systemic reform and evidence-based programmatic interventions. The Comprehensive Strategy, utilizing the best available research from what commonly became known as risk and protective factor science, brought together an array of youth-serving system professionals in a community to frame a proactive system response to juvenile delinquency. The systemic change approach of the Comprehensive Strategy supported development and implementation of a continuum of programs aimed at targeted prevention, early intervention, and graduated sanctions at every key decision point of the juvenile justice system. Jurisdictions from across the country engaged in this strategy with support and guidance provided by OJJDP.

IMPROVING DATA AND PROMOTING USEFUL RESEARCH

The 2013 NRC report expressed concern about the lack of consistent data on numerous juvenile justice issues and recent reform efforts. These limited data capacities in juvenile justice have challenged the field for many years, and the current lack of extensive data is largely the legacy of limited and unfocused resources committed to the issue of juvenile delinquency throughout the federal government. The goals outlined in the 2013 NRC report increase the challenges. Making significant advances in promoting accountability, adopting effective interventions, and increasing fairness all require more empirically sound measurement and management strategies than those now used in juvenile justice. Many current data systems at the federal and local levels are inadequate to this task. Much needs to be done to integrate advances in technology, data management, and analysis into state juvenile justice systems. Other sectors have made the effort and have reaped benefits.

OJJDP can and should take a leadership role in improving data quality and research in juvenile justice. The agency has taken such a role in the past (National Research Council, 2013, Chapter 10) and can build on its own accomplishments. In this current period, OJJDP can focus its efforts in these areas on the goal of reforming juvenile justice practice and policy. OJJDP can serve as a central coordinating point for information about innovations, promising approaches, and useful strategies. Perhaps more importantly, it can serve as a motivating force for improvements in data collection and management as well as research in juvenile justice. It can fulfill this vision of fostering innovation in two ways: (1) supporting and guiding upgrades to federal, state, local, and tribal administrative data systems; and (2) identifying and supporting collaborative research projects that capitalize on OJJDP’s program activities and those of other agencies.

Improving Administrative Data Collection and Management

Available data on juvenile justice practice is highly variable across states and localities. This variability makes it difficult to identify generalizable knowledge, mount sound reviews or studies of specific practice or policy approaches, and promote collaboration across localities regarding new practices. OJJDP could advance the field considerably by putting more effort into the development of broadly applicable methods for collecting uniform information. This could be done with consultation regarding administrative software development, efforts to increase uniformity regarding data collection methods, and activities aimed at collaborative problem solving across localities.

Many localities develop their own information management systems or contract with businesses to develop

such systems, largely de novo.17 As part of its leadership role, OJJDP could promote infrastructure and data element definitions that would both modernize existing systems and allow comparisons across localities. To promote more systemwide consistency, OJJDP could provide model formats or specifications for information management systems as well as consultation regarding the implementation of such systems. Such guidelines could be produced from ongoing consultations with localities about their successes and challenges in implementing data management systems, as well as from meetings and shared activities among data management professionals in different localities. In addition, information and expertise about data organization and management could be gathered systematically from other agencies in the Office of Justice Programs (the National Institute of Justice and Bureau of Justice Statistics) and other federal agencies with histories of mounting multisite studies requiring consistent data collection and integration (for example, the National Institutes of Health). Attention will need to be paid to the sensitive nature of juvenile justice data in order to safeguard the confidentiality of individuals’ data. Regular work groups and conferences coordinated by OJJDP could provide the necessary formats for increasing the consistency and quality of information available across state and local jurisdictions.

These efforts will have to be incremental, involving a limited set of localities at a time; it will take a great deal of effort to reach consensus among localities about processes and definitions. At the same time, the payoff from these efforts would be considerable. Improved and more uniform data systems and data collection methods across localities would make cross-site comparisons and projects possible. Jurisdictions would be able to assess the viability of improvements to their systems if they have useful and comparable data to measure recidivism rates or other key youth outcomes during and beyond periods of system supervision. If localities reached some consensus on the definition of particular operational features of their local juvenile justice systems (e.g., what constitutes a technical probation violation), they could then confidently compare outcomes across localities. This could lead to more broadly applicable knowledge, rather than singular “demonstrations” that often fail replication. In addition, natural experiments could be mounted in which different practices are used in regular practice across multiple jurisdictions and comparable data are collected at each site. Attaining an acceptable level of uniformity across localities is the necessary first step toward these types of activities. OJJDP is the only agency that is positioned to promote the needed consistency across localities.

Recommendation 3-3: OJJDP should take a leadership role in local, state, and tribal jurisdictions with respect to the development and implementation of administrative data systems by providing model formats for system structure, standards, and common definitions of data elements. OJJDP should also provide consultation on data systems as well as opportunities for sharing information across jurisdictions.

Supporting Collaborative, Applied Research with a Developmental Focus

Three orientations have dominated OJJDP’s data analysis and research efforts over recent years. The first has been a concern with documenting the functions of the system nationally, such as collecting and analyzing information on numbers of juveniles arrested, petitioned, or sent to institutions in different localities. Much of this work has been done by the National Center for Juvenile Justice, interpreting and integrating reports of system processing figures obtained from states or localities. The second major orientation has been toward the identification of individual programs that “work” to prevent or reduce delinquency among the program participants (measured almost exclusively by re-arrest data). The programs that work are compiled in the Model Programs Guide (now merged with CrimeSolutions.gov [http://www.crimesolutions.gov], the website sponsored by the Office of Justice Programs for information on criminal justice program effectiveness). The third has been the funding of selected research projects regarding factors related to the development or continuation of delinquency (e.g., the Causes and Correlates of Delinquency studies, Pathways to Desistance study, gang research, and research on effects of mentoring programs).

_________________

17Performance-based standards, as discussed in Chapter 2 and in the 2013 NRC report, provide an example of performance measures for facility safety, behavior management, health, mental health and substance abuse services, case management and reentry planning, programming and education, and connections to family and community resources (National Research Council, 2013).

There is much to be said for the value of these activities. Collecting and reporting data on systems regularities serve important management purposes. First, they indicate whether there are discernible trends over time that might inform where resources should be directed (e.g., how much of an increase is there in violent offenses by females?). These trends might indicate changes in actual offending behavior that need to be investigated or shifts in processing patterns that deserve attention. Second, these figures can provide benchmarks for localities, telling them whether their systems are operating differently from most other localities. If, for instance, a locality’s rate of institutional placement is well above that seen in other comparable sites, local administrators can examine their practices to see whether there are changes they might make to reduce this rate. Providing information about program effectiveness will give leads to practitioners about possible intervention strategies and to policy makers about ways to set funding and service priorities. Research on developmental patterns of delinquency and effects of particular factors on continued delinquency at different ages provides basic information needed to generate informed interventions and policies.

These activities alone do not, however, adequately promote a developmental perspective on juvenile justice. Data on system regularities mainly help in management decisions about how to structure the processes for handling adolescents who come to the attention of the system, but they contain little information on outcomes from intervention. Identifying and certifying programs as “working” with particular groups of adolescents promotes the idea that certain interventions or prevention programs have a universal applicability, with little attention paid to the relevant developmental outcomes connected with involvement in juvenile justice services. These approaches do not address whether the system is effective at preparing youths for becoming productive adults or whether youths have achieved critical developmental milestones that the juvenile justice system could be promoting.

OJJDP will need to promote expanded data collection to capture the effects of particular juvenile justice practices or policies on development and to understand developmental influences on the effectiveness of practices and policies. There would also need to be an emphasis on measuring outcomes beyond arrest or return to an institution and on requiring more data about system-involved adolescents from systems outside of juvenile justice. As noted in Chapter 3 of the 2013 NRC report, the systems affecting delinquent adolescents are multilayered, decentralized, and variable across localities. Juvenile justice operations intersect with schools, families, law enforcement officials, child welfare professionals, and social service providers to prevent adolescent crime, intervene with juveniles who offend, and promote public safety and justice. This reality implies that juvenile justice agencies must build collaborative relationships with these other social agencies to paint an accurate picture of how an adolescent’s life unfolds and to understand how juvenile justice involvement fits into this process.

Thus, research done in conjunction with schools, families, and social service providers is necessary to examine factors beyond just court intervention. Such work is best done in a collaborative fashion. OJJDP and state or local juvenile justice agencies need the cooperation and viewpoints from system partners (e.g., school professionals, social service providers) in conceptualizing, implementing, and interpreting research regarding efforts to prevent or respond to adolescent offending. Research on these questions is simply too complicated and expensive for individual federal, state, or local juvenile justice agencies to address on their own, across all the points of juvenile justice processing or localities: for OJJDP, this means mounting collaborative research projects with other federal agencies and promoting collaborative efforts at the state and local levels. These efforts would focus on specific and delimited questions about how the juvenile justice system interacts with school, families, and service providers to promote delinquency prevention and intervention efforts that coordinate resources among these sectors to reduce entry into the juvenile justice system, limit that involvement, or prevent re-offending. To determine how to do this, OJJDP can pursue three activities to develop a focused research portfolio to support system reform efforts.

First, OJJDP can identify opportunities to capitalize on its dual functions of funding program and research activities. Unique among Office of Justice Programs’ agencies, OJJDP has the joint mandate to fund both program initiatives and research on juvenile justice, delinquency, and prevention. There is considerable potential in integrating these two activities more closely to use program activities as platforms for research, supplementing intervention activities with resources to support applied research and data collection. To do this, OJJDP staff need to be more knowledgeable about research design and the state of delinquency research, but they do not necessarily have to be adept at conducting independent research. Their role would be that of a knowledgeable broker who can

identify collaborative opportunities and bring them to fruition. Such research activities can be coordinated with the research-practitioner partnerships and visiting fellow programs. These joint initiatives can identify intervention opportunities to collect data on aspects of adolescent development (e.g., perceptions of deterrence or indicators of perceived fairness) that might mitigate the adjustment of system-involved adolescents. It is the responsibility of OJJDP to capitalize on these possibilities.

Second, OJJDP could use outside scholarly experts on specific content areas to develop research agendas and to help identify collaborative projects that could be pursued with other federal partners (e.g., the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Science Foundation) or foundations and academic institutions. OJJDP needs to develop a more focused research portfolio, using adolescent development as an orienting principle. This can be accomplished using ad hoc committees of experts to provide research ideas and expertise about design, measurement, analysis, and interpretation of research results. Limiting research to a few topics and integrating it with OJJDP’s own program activities and those of other agencies would produce more in-depth research information on a set of high-priority issues in the field. Such an initiative would be in line with the recommendations of a previous NRC report calling for the increased use of consultants on particular topics in criminal justice agencies in general (National Research Council, 2005). It would also be the first step in moving OJJDP toward a research agenda that focuses on “why” and “how” particular programs or policies work. It would thus be a large step toward a more scientific approach to juvenile justice and delinquency research.

Third, OJJDP could advance research initiatives in the juvenile justice field by promoting data uniformity among researchers. Building comprehensive knowledge about program effects and developmental constructs (e.g., perceptions of fairness) requires consistent measurement of constructs. Currently, measures used to portray constructs or outcomes in research studies vary from investigator to investigator or agency to agency. OJJDP could propose preferred measures for constructs of interest to be used in many evaluations or research projects. Just as the agency now provides information regarding programs with proven records of success in the Model Programs Guide and at CrimeSolutions.gov, it could also provide information about measures with sound psychometric characteristics.

OJJDP’s role in promoting uniformity of research measures would largely be to serve as the arbiter of professional opinions and to endorse the use of particular forms of data collection to the field. The agency can lead by setting the standards for the field and creating incentives for others to follow. A limited requirement for uniformity in the data collected could, however, prove useful. OJJDP could provide a list of a few sound instruments for assessing certain commonly measured key constructs (e.g., peer associations). Grantees could be required to use at least one of the instruments on the list, with the option of using others of their choosing in addition to a required instrument. Enforcement of such a practice has been implemented successfully by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, whose approach could provide a useful model. Having consistent data across multiple research studies could lead to consolidations of datasets and would be a major step forward in generating broadly interpretable information.

Recommendation 3-4: OJJDP should focus research efforts toward specific projects related to a developmental perspective on juvenile justice, capitalizing on an integration of its research and program efforts.

OJJDP is poised to make a substantial contribution to the generation of more useful, accessible, and valid information to guide program implementation and policy formulation. However, achieving this possibility will require a reorientation of effort and resources. It requires a federal agency that takes the lead in identifying issues that matter to moving state systems forward; focuses its resources on projects and research that address these issues; coordinates the collection of uniform data; and works collaboratively with outside experts, academic institutions, other federal agencies, and foundations. Moving from a role as a compiler of information about programs or approaches to a promoter of strategic and efficacious practices or policies would have a profound influence on the field. This style of leadership would translate into more consistent data reporting, more informed management, and sounder, more integrated research to inform practice and policy discussions.

The effort to engage in strategic information dissemination will build momentum and sustainability such that the developmental approach to juvenile justice continues as a guiding philosophy regardless of changes in OJJDP’s leadership. OJJDP currently has the tools to export knowledge through a variety of technologies and methods. These include but are not limited to: national conferences, training symposia and forums (regional, state, and local), research briefs, newsletters, special topic reports, webcasts and webinars events, special topic meetings and trainings, guiding publications, white papers, toolkits, fact sheets, and other online resources.

OJJDP staff should develop an outreach and deployment strategy beyond the State Advisory Groups to include partner agencies and organizations at the federal level and affiliated national organizations (see Chapters 4 and 5) and to ensure that these key partners understand the basis for reform policies, are aware of the partnership opportunities for improving the juvenile justice system, and assist with the dissemination of this information to the key decision makers within their networks.

Furthermore, OJJDP should hold itself accountable for its efforts to infuse a developmental perspective into its operations. All of OJJDP’s activities discussed in this chapter, including information dissemination, better data, relevant research, and training and technical assistance, should promote the implementation of a developmental perspective in juvenile justice. If these activities are not pursued adequately or if they do not have the intended effect, OJJDP should be prepared to change its tactics. This requires that OJJDP develop a strategy to monitor its own activities, set benchmarks, and measure outcomes to determine if it has had the desired effect on the field. OJJDP has to serve as a model for self-monitoring and correction, to promote these activities more broadly in the field.