Abstract: This chapter examines the governance of graduate medical education (GME). There is no overarching system that oversees public GME funding in the interests of the nation’s health or health care workforce needs. Federal GME funding is guaranteed except for a requirement that residency programs be accredited to receive federal support. GME accreditation is essential to ensuring that GME programs meet professional standards and produce physicians that are ready to enter practice with required knowledge, experience, and skills. However, antitrust and fair trade prohibitions preclude accreditors from addressing broader national objectives such as the makeup of the physician workforce, the geographic distribution of GME resources, or other priority concerns. Under the status quo, program outcomes are neither measured nor reported. As a result, many of the most fundamental questions about the effectiveness of the Medicare GME program are currently unanswerable. These include questions regarding the financial impact of residency training programs on teaching hospitals as well as the specialties and other important characteristics of trainees that are funded by Medicare. Several critical steps are needed to ensure appropriate governance of the public’s investment in GME. The Medicare GME program should have a transparent, simple, and logical organizational infrastructure for program oversight and strategic policy development and implementation; methods to establish program goals consistent with the needs of the public that is financing the GME system; performance measures to

monitor program outcomes with respect to those goals; and easily understood reporting to the public and other stakeholders.

Common notions of good governance are based on the expectation that public programs have the capacity to ensure responsible stewardship of public funds, to provide appropriate program oversight, and to achieve defined program outcomes. Good governance also requires transparency—public access to information—to promote accountability. Assessing these principles in the context of graduate medical education (GME) is challenging. The governance of GME is perhaps best described as an intricate puzzle of interlocking, overlapping, and sometimes missing pieces. No one entity oversees the GME system—particularly with respect to the use of public monies—and comprehensive information on the standards and processes that GME governance comprises is not available. Other than a requirement that residency programs be accredited by the Accreditation for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), the Commission on Dental Accreditation, or the Council on Podiatric Education to receive federal funding, there are few statutory requirements to guide Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) stewardship of GME funds (MedPAC, 2010). The financing and governance of GME are essentially disconnected.

This chapter examines the current landscape of GME governance, focusing on oversight of Medicare’s funding of GME because it accounts for more than 90 percent of federal GME support. The chapter begins by defining accountability and describing the extent to which common accountability mechanisms are used by Medicare or other federal GME programs (see Table 4-1). It then describes selected federal entities with the potential to inform GME policy and the accreditation organizations that set and maintain the educational standards of GME programs. The chapter concludes with discussions of the potential use of performance-based metrics in Medicare GME financing and other opportunities for improving the governance of the public’s investment in GME.

Accountability is the acknowledgment and assumption of responsibility. It requires several basic elements: clarity of purpose, a responsible entity to provide program oversight, an obligation to be both transparent and answerable for results, and performance indicators to assess achievement of goals. Table 4-1 describes common mechanisms for facilitating accountability and their use in the federal GME funding programs. Except for accreditation and certification, most means of facilitating accountability,

TABLE 4-1 The Use of Accountability Mechanisms in Federal Graduate Medical Education (GME) Programs

| Mechanism | Purpose | Current Use |

| Accreditation | To evaluate, review, and certify training programs and training institutions to ensure that they meet designated standards | Accreditation by ACGME or the AOA COPTI is required by the Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Hospital GME (CHGME), and Teaching Health Centers (THCs) programs. |

| Board certification | To ensure the public that certified specialists have the knowledge and skills required to provide high-quality care in a given specialty | Board certification of graduates of GME programs is controlled by ABMS and AOA, but has no direct connection to accountability for federal GME support. |

| Financial Oversight | To ensure stewardship of public funds | No direct oversight of Medicare or Medicaid GME funding by CMS; CHGME and THCs are administered by the HRSA Bureau of Health Professions. |

| Licensure | To ensure competence to practice medicine | All states require physicians to complete at least one year of GME training to be eligible for a license. |

| Performance measurement | To assess program performance and to inform future program improvements | Not required by Medicare, Medicaid, or CHGME; THCs are “encouraged” to track some outcomes. |

| Public participation | To give voice to the public interest | Limited; some public representation on the governing boards of accrediting agencies. |

| Public reporting | To facilitate transparency and inform the public | Not required by CMS for DGME and IME funding; children’s hospitals that receive CHGME funding and THC awardees must report a variety of program details. Congress recently mandated that HRSA submit a report on CHGME. The Council on Graduate Medical Education publishes occasional reports (including policy recommendations) on various GME-related issues. |

NOTES: ABMS = American Board of Medical Specialties; ACGME = Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; AOA = American Osteopathic Association; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; COPTI = Council on Osteopathic Postgraduate Training Institutions; DGME = direct graduate medical education; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; IME = indirect graduate medical education.

SOURCES: ACGME, 2011b, 2013; AOA, 2013a.

such as an infrastructure for program oversight, performance metrics, and public reporting and participation, are absent.

What Is the Purpose of GME Funding?

Program accountability cannot be ensured without a shared understanding of the program’s purpose and outcome expectations. But what is the purpose of GME funding? The legislative record regarding the original intent of Medicare GME funding is somewhat ambiguous. It is unclear, for example, whether the original intent for the program went beyond physician training to include other health professionals. The intended duration of Medicare GME funding was also uncertain. When Congress established the Medicare program in 1965, reports from the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives observed only that1:

Many hospitals engage in substantial educational activities, including the training of medical students, internship and residency programs, the training of nurses, and the training of various paramedical personnel. Educational activities enhance the quality of care in an institution, and it is intended, until the community undertakes to bear such education costs in some other way, that a part of the net cost of such activities (including stipends of trainees, as well as compensation of teachers and other costs) should be borne to an appropriate extent by the hospital insurance program.

Later changes to the Medicare statute, described in the previous chapter, introduced additional rationale for Medicare GME payments (Nguyen and Sheingold, 2011). When the indirect medical education (IME) payment mechanism was created in 1983, for example, the stated intent was to account for costs outside the hospital’s control (Wynn et al., 2013). House and Senate committee reports noted that2:

This adjustment is provided in light of doubts … about the ability of the DRG case classification system to account fully for factors such as severity of illness of patients requiring the specialized services and treatment programs provided by teaching institutions and the additional costs associated with the teaching of residents….The adjustment for indirect medical education costs is only a proxy to account for a number of factors which may legitimately increase costs in teaching hospitals.

The context for Medicare’s role in financing GME is far different today

________________

11965 Social Security Act (Senate Report No. 404, Pt. 1 89th Congress, 1st Sess. 36 [1965]; H.R. No. 213, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. 32 [1965]).

2 House Ways and Means Committee Report, No. 98-25, March 4, 1983, and Senate Finance Committee Report, No. 98-23, March 11, 1983.

and will likely continue to evolve. The original rationale was formulated in an era when Medicare payments to hospitals were based on reasonable costs; fee-for-service reimbursement was the dominant payment method; health care services were concentrated in hospital settings; and the prospects of a substantial expansion in health insurance coverage were dim. In the more than 20 years since the IME adjustment to diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment rates was implemented, the DRG system has been refined to better reflect severity of illness, hospitals have received payments for disproportionate shares of uncompensated care, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has significantly expanded health insurance coverage.

Thus, coming to consensus on the purpose of Medicare GME funding—today and in the future—was a central focus of the committee’s early discussions. As Chapter 1 notes, the committee agreed that Medicare GME funding should be explicitly purposed to encourage production of a physician workforce better prepared to work in, to help lead, and to continually improve an evolving health care delivery system that can provide better individual care, better population health, and lower cost. Many researchers, policy makers, and stakeholders have articulated similar objectives for physician training (ACP, 2011; AHA, 2012; Boult et al., 2010; COGME, 2000, 2007b, 2010, 2013; Fuchs, 2012; Ludmerer, 2012; Ludmerer and Johns, 2005; MedPAC, 2009, 2010; Reddy et al., 2013; Salsberg, 2009; Skochelak, 2010; Weinstein, 2011).

Who Is Accountable for GME Funding?

There is no overarching system to guide GME funding in the interests of the nation’s health or local or regional health care workforce needs. CMS simply acts as a passive conduit for GME funds distribution to teaching hospitals. As the previous chapter described, GME funding is formula driven and essentially guaranteed except for the requirement that residencies be accredited to receive federal support.3 How the funds are used is at the discretion of the hospitals. Program outcomes are neither measured nor reported. To the extent there is accountability, it is the accountability of the teaching institution to its own priorities and to accreditors, not to the public that provides the funds.

Program accreditation and board certification are essential to ensuring that GME programs meet professional standards and produce physicians that are ready to enter practice with required knowledge, experience, and skills. However, accreditation and board certification cannot address broader national objectives regarding the makeup of the physician work-

________________

3 See Chapter 3 for a description of GME financing.

force, the geographic distribution of GME resources, or other priority concerns. State and federal antitrust and fair trade statutes prohibit accreditation organizations from directly engaging in issues related to the number and types of subspecialty programs or the size of residency programs (other than for reasons related to educational capacity) (Nasca, 2012).

Although not directly accountable for GME funding, several federal advisory groups and research centers, described below, are engaged in relevant activities:

- Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME): A federal advisory committee, established in 1986 to provide national leadership on GME issues and to supply relevant advice to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS); the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions; and the House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce (HRSA, 2012). COGME’s capacity to provide substantive program oversight and independent evaluation is limited by several factors. In fiscal year (FY) 2012, COGME’s appropriations totaled about $318,000 for both operations (travel and compensation for 17 Council members) and staff (1.3 FTEs) (HRSA, 2012). COGME’s mandated composition emphasizes stakeholder representation over relevant technical expertise. By law, members must include representatives of practicing physicians, physician organizations, international medical graduates, medical student and house staff associations, schools of medicine, public and private teaching hospitals, health insurers, business, and labor. Designees of the HHS Assistant Secretary for Health, CMS, and the Department of Veterans Affairs are also mandated members. There is no requirement for COGME members to have skills in research methods, health care finance, workforce analysis, or health or labor economics, or to represent the public interest. The Council’s influence is further limited by its organizational placement. It is located not in the federal agency that distributes Medicare or Medicaid GME funding, but in the Bureau of Health Professions within the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an HHS agency without a direct link to CMS and whose primary mission concerns underserved populations. COGME’s role is advisory; it lacks the regulatory authority to effect change. Although COGME has produced numerous reports, none have affected federal GME policy (COGME, 2000, 2004, 2005a,b, 2007a,b, 2010b, 2013).

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC): MedPAC is an independent congressional agency that has provided highly regarded, but only occasional, policy analysis and advice regarding

-

Medicare GME to Congress (MedPAC, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2009, 2010). In contrast to COGME, MedPAC has deep analytic expertise and knowledge of Medicare as well as considerable resources. Its staff includes approximately 25 full-time researchers with skills in economics, health policy, public health, and medicine (MedPAC, 2013). However, because Medicare GME funding accounts for less than 2 percent of total Medicare spending, it is not a principal MedPAC focus. The 17-member Commission is charged with providing advice to Congress on all issues affecting Medicare, including payment methodologies and beneficiaries’ access to and quality of care (MedPAC, 2013). The Commissioners, who have diverse backgrounds in the financing and delivery of health care services, are appointed by the Comptroller General of the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

- CMS Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI): CMMI was established under the ACA4 to develop, test, and accelerate the adoption of new payment and service delivery models (CMMI, 2012). To date, CMMI activities have not focused on GME, but the Center may have the capacity to pilot innovative GME payment methods to help identify effective incentives for aligning physician training with regional or national health care workforce priorities. CMMI began operations in FY 2011 with $10 billion in direct funding through FY 2019. Its activities focus on the models and initiatives identified in Section 3021 of the ACA. These include accountable care, bundled payments for care improvement, primary care transformation, the Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) population, the dually eligible Medicaid-Medicare population, new payment and service delivery models, and initiatives to speed the adoption of best practices. CMMI also supports other demonstration and research sponsored by CMS.

- National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (HRSA Bureau of Health Professions): The Center is charged with estimating the supply and demand for all types of health workers (HRSA, 2013b; National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, 2013). It is also responsible for methods development and related research. Although the Center’s work has the potential to inform GME policy, it does not have a direct link to CMS.

________________

4 Section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act; 42 U.S.C. 1315 (Section 1115A of the Social Security Act).

- National Health Care Workforce Commission: Also created under the ACA,5 the Commission was established to address the implications of federal policies for the health care workforce—including GME. It has never received appropriations and is inactive.

Transparency

One of the most striking messages from the previous chapters is how little is known about the management and effectiveness of the public’s more than $15 billion annual investment in GME. Teaching hospitals are only required to report the data elements that Medicare uses to calculate the GME payment amounts (see Table 4-2) (CMS, 2013). Medicaid GME data are neither collected nor reported (Henderson, 2013; Herz and Tilson, 2009). The available GME data from CMS and the teaching hospitals have limited use for program oversight, workforce analysis, or policy making.

As a result, many of the most fundamental questions about the outcomes and effectiveness of the Medicare GME program are currently unanswerable. These include, for example:

- What is the financial impact of residency training programs on teaching hospitals and other GME training sites that sponsor them?

- What are the differences in training costs by specialty, type of training site, geographic location, sponsor, program size, or patient population?

- What are the institutional revenues or savings generated by residents?

- Do these programs produce competent doctors?

- Are the physicians trained to provide coordinated care across health care settings?

- Are the physicians trained in the skills required for patient safety?

- How much does each teaching institution receive in Medicare GME funding each year? What proportion of these payments is used for educational purposes?

- Who are the trainees supported by GME funding? What are their specialties and racial and ethnic, socioeconomic, and other relevant characteristics?

- Of those trainees whose residencies are subsidized by the public, how many go on to practice in underserved specialties, to locate in underserved areas, or to accept Medicare and Medicaid patients?

________________

5 Public Law 111-14, Subtitle B—Innovations in the Health Care Workforce.

TABLE 4-2 Current Federal Reporting Requirements for GME Programs

| Program/Agency | Reported Information | Reporting Responsibility | Report Recipient |

| Medicare GME/CMS |

Medicare statute requires that GME sponsors report the data elements needed to calculate IME and DGME payment, including:

• Annual direct GME costs • Number of FTE trainees in their initial residency period • Amount of time residents spend on rotations at various locations • Intern and resident to bed ratio • Medicare bed ratio |

Teaching hospitals and other sponsoring organizations | CMS |

| Medicaid GME/CMS | No reporting requirements | None | None |

| Children’s Hospitals GME (CHGME)/HRSA |

CHGME 2006 reauthorization mandated that program participants report:

• Types and number of training programs by specialty and subspecialty • Types of training related to the needs of underserved children • First practice location of graduates • Curricular focus of training programs • Other program details |

Participating children’s hospitals | HRSA |

| HRSA summarizes the individual reports and recommends program improvements. | HRSA | Congress | |

| Teaching Health Centers (THCs)/HRSA |

THC authorizing legislation mandated that program awardees report the number of:

• Accredited training programs • Approved part-time or full-time equivalent training positions • Primary care physicians and dentists who completed training in the THC • Program graduates who currently care for vulnerable populations • Other information “deemed appropriate,” e.g., residents’ demographics, rural background, and medical education |

Participating THCs | HRSA |

| In addition: | |||

|

• Awardees are “encouraged to track” graduates’ practice types and locations for 5 years after completing training • Total compensation for funding recipients’ and subrecipients’ five most highly paid executives |

|||

| VHA GME/Veterans Affairs | No reporting requirements; however, the VHA Office of Academic Affiliations has full access to all residency program data from VHA teaching institutions. | Not applicable | NA |

NOTE: CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DGME = direct graduate medical education; FTE = full-time equivalent; GME = graduate medical education; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; IME = indirect medical education.

SOURCES: CMS, 2012a; HRSA, 2011, 2013c.

- What proportion of trainees’ time is spent in inpatient care, hospital outpatient, and community-based settings?

- Are the program’s trainees trained in a variety of clinical settings where physicians in that specialty provide care?

Two Noteworthy Exceptions

The VHA Office of Academic Affiliations tracks its facilities’ GME costs and has access to a full range of information on its residency programs. As a result, researchers have been able to analyze a variety of important questions, such as the impact of training programs on staff physicians’ productivity, specialty differences in the intensity of resident supervision, and residents’ increasing independence during training (Byrne et al., 2010; Coleman et al., 2003; Kashner et al., 2010).

The HRSA Children’s Hospitals GME (CHGME) and Teaching Health Center (THC) programs have specific reporting requirements that provide the potential for assessments of their effectiveness. The authorizing legislation6 for these programs mandates that HRSA produce routine reports on a range of funds recipients’ characteristics and outcomes. The first CHGME report was published in 2013 (HRSA, 2013c). HRSA has funded a comprehensive 5-year THC evaluation plan with periodic reports (HRSA, 2013a).

GME ACCREDITATION AND CERTIFICATION

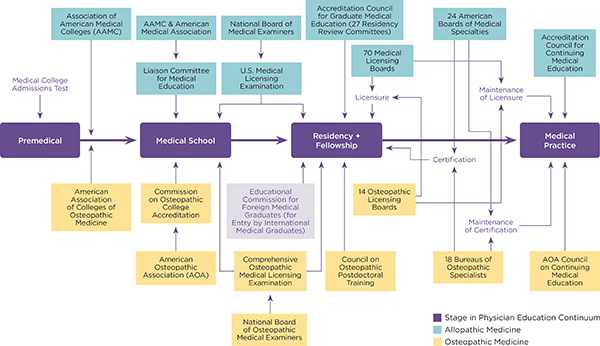

Accreditation and certification are forms of professional self-regulation. In GME, the professions establish their own standards and processes to ensure that the curriculums and conduct of residency programs can be expected to produce competent physicians. Along the continuum of physician education, there are multiple accrediting entities that oversee physician training programs and institutions, and dozens of certifying and licensing organizations that affirm individuals’ readiness to practice (see Figure 4-1). In addition to ACGME and the Council on Osteopathic Postgraduate Training (COPT), numerous specialty societies and other organizations provide program accreditation (especially for subspecialty education). Approximately 200 organizations (often physician specialty societies) provide physician certification in various subspecialty areas of practice (ABMS, 2013a). There are 70 allopathic and 18 state osteopathic agencies that control licensure to practice.

________________

6 The CHGME reporting requirements were introduced in its 2006 reauthorization. When this report was drafted, future CHGME funding was uncertain.

Because of the dearth of federal oversight, accountability for Medicare GME funding has essentially been delegated—de facto—to the private organizations that accredit or certify GME training institutions and residency programs. As noted earlier, all federal GME funding—Medicare, Medicaid, CHGME, and THCs—is contingent on accreditation (Social Security Administration, 2014).

Graduates of GME programs become eligible for board certification through specialty and subspecialty boards. Although it is voluntary, most physicians pursue certification. Board certification—which does not qualify programs for federal GME funding—is a designation conferred by one or more of the specialty boards and is intended to ensure the public that certified physicians have the knowledge, experience, and skills that the relevant board deems necessary for delivering high-quality care (ABMS, 2013a,b; Shaw et al., 2009). Certification is not required to practice medicine in any state, because medical licenses are not specialty specific (Nora, 2013). It is, however, increasingly required by hospitals and other health care organizations as a condition of employment or practice privileges and by health insurers as a condition of physician enrollment.

As Table 4-3 indicates, the organizations that govern GME program accreditation and individual physician certification are private, non-profit entities funded largely by membership dues and/or application and examination fees. The specialty boards and other organizations conferring certification are typically led by physicians, whereas the accreditation organizations are led by a broader range of stakeholders, sometimes including representatives of the public.

The dual tracks of allopathic and osteopathic medicine present a particular challenge to understanding the accreditation and certification processes. As Figure 4-1 and Table 4-4 illustrate, there are parallel allopathic and osteopathic standard-setting organizations for GME training programs and institutions and also specialty certification. In March 2014, the two organizations announced an agreement to transition to a single accreditation system for GME by 2020 (Nasca et al., 2014b). The committee applauds this initiative and other ACGME and AOA efforts to better pre-

TABLE 4-3 Private Organizations That Have a Governance Role in GME

| Organization | Role in GME | Funding and Leadership |

| Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) | Sets GME institutional accreditation standards for institutions and programs; oversees the accreditation process through its 28 Residency Review Committees (RRCs) and Institutional Review Committee | Private, non-profit funded primarily by program fees. The Board of Directors is nominated by ABMS, AHA, AMA, AAMC, and CMSS and includes public members, at-large members, residents, and non-voting VA and HHS representatives. |

| Organization | Role in GME | Funding and Leadership |

| American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) | To support the specialty certification activities of its member boards | Private, non-profit funded by member dues and licensing fees. The Board of Directors includes representatives of medical specialty boards; associate board members represent AAMC, ACCME, ACGME, AHA, AMA, CMSS, ECFMG, FSMB, and NBME. |

| Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists | Oversees specialty certification, including standards setting and implementation | Funded by AOA. The Bureau includes one representative from each AOA-approved certifying board as well as a chair, vice chair, and public member appointed by the AOA president. |

| Council on Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training | Determines GME accreditation standards and oversees the accreditation process | Funded by AOA. Council members include representatives from OPTI, AACOM, AMOPS, BOH, and BOME; representatives from specialty practice affiliates; an AOA member-at-large; and an intern/resident. |

| Council on Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training Institutions | Accredits osteopathic postdoctoral (GME) training institutions and consortiums | Funded by AOA. Chair is appointed by the AOA President. Members include representatives of AACOM, AODME, and AOA BOH; OPTI administrators and educators; and a student and intern/resident. |

| Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates | Certifies the eligibility of international medical graduates for U.S. training programs | Private, non-profit funded by application and licensing/exam fees. Board of Trustees includes organizational members (ABMS, AMA, AAMC, AHME, FSMB, NMA), Trustees-at-Large, and ECFMG president. |

| Individual medical specialty boards | Set standards for specialty/subspecialty board certification; develop and administer certifying exams | Private, non-profit organizations funded by member dues. |

| RRCs | Have delegated authority from the ACGME to set standards for and accredit residency training programs | RRC members are nominated by the AMA Council on Medical Education, ABMS, and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies. |

NOTES: AACOM = American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine; AAMC = Association of American Medical Colleges; ACCME = Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; AHA = American Hospital Association; AHME = Association for Hospital Medical Education; AMA = American Medical Association; AMOPS = Association of Military Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons; AODME = Association of Osteopathic Directors and Medical Educators; BOH = Bureau of Hospitals; BOME = Bureau of Osteopathic Medical Educators; CMSS = Council of Medical Specialty Societies; ECFMG = Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates; FSMB = Federation of State Medical Boards; GME = graduate medical education; NBME = National Board of Medical Examiners; NMA = National Medical Association; OPTI = Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training Institution.

SOURCES: ACGME, 2011b, 2013; AOA, 2008, 2012, 2013a,c.

| Functions | ACGME | BOE & AOA Board of Trustees | ABMS | Other Medical Specialty Boards | Other Osteopathic Specialty Boards | RRCs | PTRC | Osteopathic Specialty Colleges | COPTI | COPT | ECFMG | NBME | BOS | NBOME |

| Sets standards: | ||||||||||||||

| GME training programs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| GME training institutions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Specialty certification | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| GME Osteopathic Consortia | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Accredits: | ||||||||||||||

| GME training programs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| GME training institutions | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| GME Osteopathic Consortia | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Certifies: | ||||||||||||||

| IMG trainees’ eligibility for GME | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Specialty board certification of individual trainees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Physician licensing | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

NOTES: ABMS = American Board of Medical Specialties; ACGME = Accreditation Council for GME; AOA = American Osteopathic Association; BOE = Bureau of Osteopathic Education; BOS = Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists; COPT = Council on Postdoctoral Training; COPTI = Council on Osteopathic Postdoctoral Training Institutions; ECFMG = Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates; GME = graduate medical education; NBME = National Board of Medical Examiners; NBOME = National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners; PTRC = Osteopathic Program & Training Review Council; RRC = Residency Review Committee.

pare physicians for contemporary health care delivery (AOA, 2013b; Buser and Hahn, 2013; Nasca et al., 2010). Both organizations are currently modifying their processes in order to cultivate continuous improvement in GME (Nasca et al., 2012; Shannon et al., 2013).

New Directions in Accreditation: Focusing on Competency and Outcomes

In 1998, the ACGME initiated the “Outcome Project,” the beginning of an important shift toward competency-based and outcomes-oriented GME accreditation (Swing et al., 2007). The following year, ACGME introduced six domains of clinical competency—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—to frame future GME curriculum development and program evaluation (Nasca et al., 2010).

In 2009, ACGME began The Next Accreditation System (NAS), a fundamental restructuring of the accreditation process with three primary objectives: to improve the ability of the system to prepare physicians for 21st-century practice; to accelerate the system’s transition from a focus on process to a system based on educational outcomes; and to lessen the administrative burden of complying with accreditation standards (Nasca et al., 2012). Every ACGME-accredited residency program will be required to demonstrate that its trainees achieve competencies in the six domains. Phased implementation of NAS began in 2013; July 2014 is the target date for full implementation by all specialties (Nasca et al.., 2012, 2014a).

A key component of the NAS is its emphasis on training and learning sites through the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER). The initial report on the results of more than 100 CLER visits to teaching hospitals focused on residents’ involvement in patient safety and clinical quality improvement activities (Nasca et al., 2014b). These early visits found that the environments for the clinical training of residents often lacked the desired opportunities for trainee learning (Weiss et al., 2013). The site visitors will return to institutions on a regular basis, pointing out deficiencies and outlining requirements for improvement.

Performance Metrics

Performance metrics that are tied to financial incentives are increasingly used by CMS, private payers, and others to improve the delivery and outcomes of health care (Berenson et al., 2013; GAO, 2012; Kaiser Health News, 2012; National Quality Forum, 2013; RTI International and Telligen, 2012). The measures are most commonly used in public reporting and provider incentive programs. CMS now employs more than 100 performance measures in Medicare (RTI International and Telligen, 2012) and routinely issues reports that compare the performance of competing health plans, home health agencies, hospitals, and nursing homes (CMS, 2012b). Medicare also links the measures with financial incentives or penalties in its pay-for-performance programs.

Mirroring ACGME’s ongoing transition to outcomes-based accreditation, MedPAC, COGME, the American College of Physicians, and others have called on CMS to introduce GME performance metrics and outcomes-based GME payment in the Medicare program (ACP, 2011; Baron, 2013; COGME, 2007; Goodman and Robertson, 2013; Johns, 2010; MedPAC, 2009, 2010; Swensen et al., 2010; Weinstein, 2011). Chapter 2 described the evidence that newly trained physicians are not adequately prepared for contemporary practice. GME payment should reward educational outcomes that are aligned with the standards of a high-performance health care system. The triple aim will not be achieved unless physicians are skilled in care coordination, efficient use of resources, quality improvement, cultural competence, and other essential areas.

In its 2010 review of the educational priorities in GME financing, MedPAC recommended that Medicare’s GME payments be performance based and contingent on agreed-upon objectives for the GME system (without systematically advantaging or disadvantaging particular types of training institutions or programs) (Hackbarth and Boccuti, 2011; MedPAC, 2010). MedPAC urged the Secretary of HHS to establish an expert advisory body—including representatives of accrediting and certification organizations, residency training programs, health care organizations, health care purchasers and insurers, and patient and consumer groups—to recommend new measures for that purpose (Hackbarth and Boccuti, 2011).

Feasibility

Although there are no nationally agreed-upon GME performance measures, the feasibility of measuring some GME outcomes has been demonstrated in a number of recent studies. Chen et al. (2013), for example, used data from Medicare claims files, the American Medical Association (AMA) physician masterfile, and National Health Service Corps (NHSC) data to examine the career choices and practice locations of graduates from residencies in primary care, internal medicine, psychiatry, and general surgery. The Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Practice and Primary Care, an independent research center within the American Academy of Family Physicians, has developed an interactive online tool—the “GME outcomes mapper”—to enable users to examine selected outcomes for individual GME sponsoring organizations and primary teaching sites by state and nationwide (Graham Center, 2013).7 The available outcomes are the number of residency graduates; percentage of residency graduates in primary care (including the percentage of internal medicine graduates who stay in

________________

7 Available at http://www.graham-center.org/online/graham/home/tools-resources/gme-mapper.html (accessed June 13, 2013).

primary care), general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, and psychiatry; and the percentage practicing in rural areas. In a study focused on clinical outcomes, Asch and colleagues (2014) used maternal complications of delivery as a measure to assess the training of obstetricians.

What to Measure and Report to the Public

As noted earlier in the chapter, there are many basic, unanswered questions regarding outcomes of GME funding. MedPAC has recommended that the Secretary of HHS publish an annual report detailing Medicare payments to each hospital and each hospital’s associated costs, the number of supported residents and other health professionals, and Medicare’s share of the teaching costs (MedPAC, 2010). Others have suggested that public reports should include outcomes related to agreed-on GME objectives (Johns, 2010; Weinstein, 2011). Such outcomes could include key characteristics of the residents supported by Medicare funds (e.g., specialty and subspecialty, race/ethnicity, practice in underserved areas and with vulnerable populations, residents’ time training in community-based settings).

The GME accreditation system is an essential foundation for the governance of GME. As the accreditation and certification processes transition to a competency-based and outcomes-oriented system, GME program standards will be increasingly in sync with the objectives of a high-performing health care system. In addition, the proposed unification of the ACGME and AOA GME standards has the potential to simplify accreditation and provide important efficiencies. However, antitrust regulations preclude accreditors from addressing broader, crucial system-wide objectives such as the competencies and makeup of the physician workforce or the geographic distribution of GME resources.

What Is Missing in GME Governance?

The critical missing piece in GME governance is the stewardship of the public’s investment. The public has the right to expect that its investment will be used to produce the types of physicians that today’s health care system requires. Under the status quo, there are no mechanisms or basic infrastructure to make this possible.

The Medicare GME program clearly needs an organizational infrastructure for strategic policy development and implementation and program oversight. At a minimum, it should have:

- Robust resources with sufficient expert staff and the capacity to conduct or sponsor demonstrations of alternative payment methods. MedPAC, for example, has an estimated $11.5 million budget, 17 commissioners, and about 25 professional staff members.8 Its portfolio is far more extensive than GME; the Medicare GME entity could be smaller.

- Regulatory authority to administer Medicare GME spending and oversee GME payment policies—The governing entities should have the ability to collect administrative data and to direct changes in practices. This requires a close organizational linkage with the Medicare program.

- Independence and objectivity with protections from conflicts of interest—Members of the governing body should disclose potential conflicts of interest. Individuals with clear financial interests should be consulted.

- A governing body selected with appropriate expertise in physician education, accreditation and certification, health care workforce; health care finance and economics, education of health professionals other than physicians (including advanced practice nurses and physician assistants, research methods); cultural competence; underserved populations (both rural and urban); performance measurement and quality improvement.

- A mechanism to solicit the input of representatives of accrediting and certifying bodies, training programs, health care organizations, payers, and patient and consumer groups.

The committee reviewed a range of alternatives that might incorporate the above features. Pragmatic considerations—particularly the potential for actual implementation—were another consideration. The fate of the authorized but unfunded National Health Care Workforce Commission is particularly instructive. Although the significant gap in information on the makeup of the health care workforce has been noted for many years, Congress has not provided any appropriations for the Commission’s operations. A private entity might have appealing features, but it would require a new source of funds (an unlikely prospect) and it could not direct the allocation of Medicare funds. The federal agencies that currently provide advice on GME policy are not situated to effect change. COGME is a small federal advisory committee to an HHS agency—the HRSA Bureau of Health Professions—without any regulatory authority over Medicare spending. MedPAC has deep analytic resources but, because it is a congressional

________________

8 MedPAC budget data provided via personal communication with Mark Miller, Executive Director, MedPAC, May 16, 2013.

agency, it cannot direct an executive branch agency’s (i.e., CMS’s) activities such as the distribution of Medicare funds. The likelihood of sufficient resources over a sustained period was another critical consideration. As Chapter 3 noted, GME-related programs that are subject to the appropriations cycle are often uncertain about future funding.

In conclusion, the current governance of GME financing is inadequate. The accreditation system demands high educational standards and it is making significant strides toward 21st-century health system objectives. But accreditation alone cannot ensure that the physician workforce meets the nation’s needs. An accountable governance infrastructure should be created to assure the public that its annual multibillion-dollar investment in GME produces skilled physicians prepared to work in, to help lead, and to continually improve the health care system. There is no ideal organizational arrangement for establishing that infrastructure. Placing it within HHS ensures a close organizational linkage with the Medicare program and the potential to reward program outcomes.9

ABMS (American Board of Medical Specialties). 2013a. American Board of Medical Specialties board certification editorial background. http://www.abms.org/news_and_events/media_newsroom/pdf/abms_editorialbackground.pdf (accessed November 19, 2013).

ABMS. 2013b. What board certification means. http://www.abms.org/About_Board_Certification/means.aspx (accessed September 10, 2013).

ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education). 2011a. Glossary of terms. http://acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/ab_ACGMEglossary.pdf (accessed December 2, 2013).

ACGME. 2011b. Focus on the future. Annual report. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/ACGME-2011_AR_F.pdf (accessed December 2, 2013).

ACGME. 2012a. Family medicine guidelines related to utilization of hospitalists. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/294/ProgramandInstitutionalGuidelines/MedicalAccreditation/FamilyMedicine/Hospitalists.aspx (accessed December 2, 2013).

ACGME. 2012b. Frequently asked questions: Internal medicine review committee for internal medicine. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/FAQ/140_Internal_Medicine_FAQs.pdf (accessed December 1, 2013).

ACGME. 2013. ACGME policies and procedures. Effective July 1, 2013. http://acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/ab_ACGMEPoliciesProcedures.pdf (accessed September 23, 2013).

ACP (American College of Physicians). 2011. Aligning GME policy with the nation’s health care workforce needs: A position paper. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians.

AHA (American Hospital Association). 2012. Lifelong learning: Physician competency development. http://www.ahaphysicianforum.org/team-based-care/physician-competency/index.shtml (accessed May 28, 2014).

________________

9 Chapter 5 further outlines the committee’s recommendations for a GME policy infrastructure.

AOA (American Osteopathic Association). 2008. Handbook of the council on postdoctoral training (COPT). http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/accreditation/postdoctoraltraining-approval/Documents/handbook-of-the-council-on-postdoctoral-training.pdf (accessed November 19, 2013).

AOA. 2012. Osteopathic postdoctoral training institution (OPTI) accreditation handbook. http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/accreditation/postdoctoral-training-approval/Documents/opti-accreditation-handbook.pdf (accessed November 19, 2013).

AOA. 2013a. The basic documents for postdoctoral training. http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/accreditation/postdoctoral-training-approval/postdoctoral-training-standards/Documents/aoa-basic-document-for-postdoctoral-training.pdf (accessed September 24, 2013).

AOA. 2013b. FAQs—ACGME unified accreditation system. http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/Pages/acgme-frequently-asked-questions.aspx (accessed October 14, 2013).

AOA. 2013c. Annual Report FY13. http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/about/leadership/Documents/aoa-annual-report-2013.pdf (accessed October 14, 2013).

Asch, D. A., S. Nicholson, S. K. Srinivas, J. Herrin, and A. J. Epstein. 2014. How do you deliver a good obstetrician? Outcome-based evaluation of medical education. Academic Medicine 89(1):24-26.

Baron, R. B. 2013. Can we achieve public accountability for graduate medical education outcomes? Academic Medicine 88(9):1199-1201.

Berenson, R. A., P. J. Pronovost, and H. M. Krumholz. 2013. Achieving the potential of health care performance measures. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2013/rwjf406195 (accessed May 15, 2013).

Boult, C., S. R. Counsell, R. M. Leipzig, and R. A. Berenson. 2010. The urgency of preparing primary care physicians to care for older people with chronic illnesses. Health Affairs 29(5):811-818.

Buser, B. R., and M. B. Hahn. 2013. Building the future: Educating the 21st century physician. http://mededsummit.net/uploads/BRC_Building_the_Future__Educating_the_21st_Century_Physician__Final_Report.pdf (accessed October 20, 2013).

Byrne, J. M., M. Kashner, S. C. Gilman, D. C. Aron, G. W. Cannon, B. K. Chang, L. Godleski, R. M. Golden, S. S. Henley, G. J. Holland, C. P. Kaminetzky, S. A. Keitz, S. Kirsh, E. A. Muchmore, and A. B. Wicker. 2010. Measuring the intensity of resident supervision in the Department of Veterans Affairs: The resident supervision index. Academic Medicine 85(7):1171-1181.

Chen, C. P., S. Petterson, R. L. Phillips, F. Mullan, A. Bazemore, S. D. O’Donnell. 2013. Towards graduate medical education accountability: Measuring the outcomes of GME institutions. Academic Medicine 88(9):1267-1280.

CMMI (Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation). 2012. CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation: Report to Congress. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/RTC12-2012.pdf (accessed April 18, 2013).

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2012a. 42 C.F.R.—Public Health, regulation, § 413.75, Direct GME payments: General requirements. http://cfr.regstoday.com/42cfr413.aspx (accessed April 18, 2013).

CMS. 2012b. CMS quality measurement programs characteristics. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/Downloads/CMSQualityMeasurementProgramsCharacteristics.pdf (accessed December 3, 2013).

CMS. 2013. Chapter 40: Hospital and hospital health care complex cost report. (Form CMS-2552-10). http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/Downloads/R4P240.pdf (accessed August 19, 2013).

COGME (Council on Graduate School Medical Education). 2000. Fifteenth report: Financing graduate medical education in a changing health care environment. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

COGME. 2004. Resource paper: State and managed care support for graduate medical education: Innovations and implications for federal policy. http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/Publications/managedcarerpt.pdf (accessed June 27, 2013).

COGME. 2005a. Sixteenth report: Physician workforce policy guidelines for the United States. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

COGME. 2005b. Seventeenth report: Minorities in medicine: An ethnic and cultural challenge for physician training: An update. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

COGME. 2007a. Eighteenth report: New paradigms for physician training for improving access to health care. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

COGME. 2007b. Nineteenth report: Enhancing flexibility in graduate medical education. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

COGME. 2010. Twentieth report: Advancing primary care. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

COGME. 2013. Twenty-first report: Improving value in graduate medical education. http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/Reports/twentyfirstreport.pdf (accessed February 25, 2014).

Coleman, D. L., E. Moran, D. Serfilippi, P. Mulinski, R. Rosenthal, B. Gordon, and R. P. Mogielnicki. 2003. Measuring physicians’ productivity in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Academic Medicine 78(7):682-689.

Cronenwett, L., and V. J. Dzau, editors. 2010. Who will provide primary care and how will they be trained? Proceedings of a conference sponsored by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Durham, NC, January 8-11.

Fuchs, V. R. 2012. The structure of medical education—it’s time for a change. The Alan Gregg lecture given at the annual meeting of the Association of American Medical Colleges, November 6, 2011. In More health reform. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Pp. 1-5. http://siepr.stanford.edu/system/files/shared/people/homepage/HealthCareReform_2012.pdf (accessed August 29. 2014).

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2012. Medicare physician payment: Private-sector initiatives can help inform CMS quality and efficiency incentive efforts. http://www.gao.gov/assets/660/651102.pdf (accessed December 1, 2013).

Goodman, D., and R. Robertson. 2013. Accelerating physician workforce transformation through competitive graduate medical education funding. Health Affairs 32(11): 1887-1892.

Graham Center. 2013. GME outcomes mapper. http://www.graham-center.org/online/graham/home/tools-resources/gme-mapper.html (accessed June 13, 2013).

Hackbarth, G., and C. Boccuti. 2011. Transforming graduate medical education to improve health care value. New England Journal of Medicine 364(8):3p.

Henderson, T. M. 2013. Medicaid graduate medical education payments: A 50-state survey. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Medicaid%20Graduate%20Medical%20Education%20Payments%20A%2050-State%20Survey.pdfitat (accessed June 22, 2013).

Herz, E., and S. Tilson. 2009. CRS report: Medicaid and graduate medical education. http://aging.senate.gov/crs/medicaid8.pdf (accessed September 29, 2012).

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2011. Teaching Health Center GME Program RFP-12-029 final. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

HRSA. 2012. Charter: Council on Graduate Medical Education. http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/About/charter.pdf (accessed April 26, 2013).

HRSA. 2013a. Federal Register Vol. 78, No. 113. Agency information collection activities; proposed collection; public comment request. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-201306-12/pdf/2013-13918.pdf (accessed March 5, 2014).

HRSA. 2013b. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/index.html (accessed December 3, 2013).

HRSA. 2013c. Report to Congress: Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education (CHGME) Payment Program. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/childrenshospitalgme/pdf/reporttocongress2013.pdf (accessed June 21, 2013).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2004. In the nation’s compelling interest: Ensuring diversity in the health care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johns, M. M. E. 2010. Ensuring an effective physician workforce for America. Proceedings of a conference sponsored by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Atlanta, GA, October 24-25. New York: Josiah Macy Jr. Macy Foundation.

Kaiser Health News. 2012. Medicare discloses hospitals’ bonuses, penalties based on quality. http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2012/december/21/medicare-hospitals-valuebased-purchasing.aspx (accessed December 1, 2013).

Kashner, T. M., J. M. Byrne, B. K. Chang, S. S. Henley, R. M. Golden, D. D. Aron, G. W. Cannon, S. C. Gilman, G. J. Holland, C. P. Kaminetzky, S. A. Keitz, E. A. Muchmore, T. K. Kashner, and A. B. Wicker. 2010. Measuring progressive independence with the Resident Supervision Index: Empirical approach. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2:17-30.

Ludmerer, K. 2012. The history of calls for reform in graduate medical education and why we are still waiting for the right kind of change. Academic Medicine 87:34-40.

Ludmerer, K., and M. Johns. 2005. Reforming graduate medical education. JAMA 294: 1083-1087.

MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 1999. Report to the Congress: Rethinking Medicare’s payment policies for graduate medical education and teaching hospitals. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

MedPAC. 2001. Chapter 10—Treatment of the initial residency period in Medicare’s direct graduate medical education payments. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

MedPAC. 2003. Impact of the resident caps on the supply of geriatricians. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

MedPAC. 2009. Report to Congress: Improving incentives in the Medicare program. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

MedPAC. 2010. Graduate medical education financing: Focusing on educational priorities. In Report to Congress: Aligning incentives in Medicare. Washington, DC: MedPAC. Pp. 103-126.

MedPAC. 2013. About MedPAC. http://www.medpac.gov/about.cfm (accessed November 19, 2013).

Nasca, T. J. 2014. Letter from Thomas J. Nasca, CEO, ACGME, to members of the graduate medical education community, March 13, 2014. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/NascaLetterACGME-AOA-AACOMAgreementMarch2014.pdf (accessed March 15, 2014).

Nasca, T. J., I. Philibert, T. Brigham, and T. C. Flynn. 2012. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. New England Journal of Medicine 366:1051-1056.

Nasca, T., K. Weiss, J. Bagian, and T. Brigham. 2014a. The accreditation system after the “next accreditation system.” Academic Medicine 89(1):27-29.

Nasca, T. J., K. B. Weiss, and J. P. Bagian. 2014b. Improving clinical learning environments for tomorrow’s physicians. New England Journal of Medicine 370(11):991-993.

National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, HRSA Bureau of Health Professions. 2013. Projecting the supply and demand for primary care practitioners through 2020. Rockville, MD: HRSA.

NQF (National Quality Forum). 2013. MAP pre-rulemaking report: 2013 recommendations on measures under consideration by HHS: Final report. Washington, DC: NQF.

Nguyen, N. X., and S. H. Sheingold. 2011. Indirect medical education and disproportionate share adjustments to Medicare inpatient payment rates. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review 1(4):E1-E19.

Nora, L. M. 2013. Letter from Lois M. Nora, president and CEO, ABMS, to Congressman Danny Davis, April 19, 2013. http://www.abms.org/News_and_Events/pdfs/20130419_CL_RepDavis.pdf (accessed December 4, 2013).

Office of Academic Affiliations, Veterans Health Administration. 2009. The Report of the Blue Ribbon Panel on VA-Medical School Affiliations. Transforming an historic partnership for the 21st century. http://www.va.gov/oaa/archive/BRP-final-report.pdf (accessed June 26, 2013).

Reddy, A. T., S. A. Lazreg, R. L. Phillips, A. W. Bazemore, and S. C. Lucan. 2013. Toward defining and measuring social accountability in graduate medical education: A stakeholder study. Journal of Graduate Medical Education (September):439-445.

RTI International and Telligen. 2012. Accountable care organization 2013 program analysis: Quality performance standards, narrative measure specifications. Report prepared for the CMS Quality Measurement & Health Assessment Group. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ACO-NarrativeMeasures-Specs.pdf (accessed December 1, 2013).

Salsberg, E. 2009. Annual state of the physician workforce address. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/download/82844/data/annualaddress09.pdf (accessed January 28, 2013).

Shannon, S. C., B. R. Buser, M. B. Hahn, J. B. Crosby, T. Cymet, J. S. Mintz, and K. J. Nichols. 2013. A new pathway for medical education. Health Affairs 32(11):1899-1905.

Shaw, K., C. Cassel, C. Black, and W. Levinson. 2009. Shared medical regulation in a time of increasing calls for accountability and transparency: Comparison of recertification in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. JAMA 302(18):2008-2014.

Skochelak, S. E. 2010. A decade of reports calling for change in medical education: What do they say? Academic Medicine 85(9):S26.

Social Security Administration. 2014. Compilation of the Social Security laws. Section 1886. [42 U.S.C. 1395ww] payment to hospitals for inpatient hospital services. http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1886.htm (accessed March 4, 2014).

Swensen, S., G. Meyer, E. Nelson, Hunt, Jr., D. Pryor, J. Weissberg, G. Kaplan, J. Daley, G. Yates, M. Chassin, B. James, and D. Berwick. 2010. Cottage industry to postindustrial care—The revolution in health care delivery. New England Journal of Medicine 362(5):e12.1-e12.4.

Swing, S. R. 2007. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Medical Teacher 29(7):648-654.

Weinstein, D. 2011. Ensuring an effective physician workforce for the United States. Recommendations for graduate medical education to meet the needs of the public. Proceedings of a conference sponsored by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Atlanta, GA, May 16-19. New York: Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.

Weiss, K. B., J. P. Bagian, and T. J. Nasca. 2013. The clinical learning environment: The foundation of graduate medical education. JAMA 309(16):1687-1688.

Wynn, B. O., R. Smalley, and K. Cordasco. 2013. Does it cost more to train residents or to replace them? A look at the costs and benefits of operating graduate medical education programs. Washington, DC: RAND Health.