Since the creation of the Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965, the public has provided tens of billions of dollars to fund graduate medical education (GME), the period of residency and fellowship that is provided to physicians after they receive an allopathic or osteopathic medical degree.2 In 2012 alone, public tax dollars contributed more than $15 billion to support residency training, with more than 90 percent coming from the Medicare and Medicaid programs (an estimated $9.7 billion and $3.9 billion, respectively). This funding is essentially guaranteed—regardless of whether the funded programs reflect local, regional, or national health care priorities. The scale of government support for this phase of physician education is unlike that given to any other profession in the nation. The length of postgraduate training for physicians is also unique among the professions: Board certification in a specialty typically requires 3 to 7 years of training, or longer in some subspecialties.

The United States has a robust GME system, one emulated by many other nations, with significant capacity to produce a high-quality physician workforce. Yet, in recent decades, the need for improvements to the GME system has been highlighted by blue ribbon panels, public- and private-sector commissions, provider groups, and Institute of Medicine (IOM) committees. Reports from these groups have indicated a range of concerns, including

________________

1 This summary does not include references. Citations appear in subsequent chapters.

2 GME training and funding are also available in dentistry and podiatry. Consideration of GME for these professions was outside the scope of this study.

- a mismatch between the health needs of the population and specialty makeup of the physician workforce;

- persistent geographic maldistribution of physicians;

- insufficient diversity in the physician population;

- a gap between new physicians’ knowledge and skills and the competencies required for current medical practice; and

- a lack of fiscal transparency.

In early 2012, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation asked the IOM to conduct an independent review of the goals, governance, and financing of the GME system. The Macy Foundation’s funding spurred additional support from 11 private foundations (ABIM Foundation, Aetna Foundation, The California Endowment, California HealthCare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, East Bay Community Foundation, Jewish Healthcare Foundation, Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Policy, Missouri Foundation for Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and UnitedHealth Group Foundation), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Eleven U.S. senators, from both sides of the aisle, also expressed support.

The IOM Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education was appointed in the summer of 2012. The committee’s charge was to review GME financing and governance and to recommend policies for improving it, with particular emphasis on physician training (see Box S-1). The 21-member committee included experts from the full continuum of physician education (allopathic and osteopathic); nursing and

BOX S–1

Charge to the IOM Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education

An ad hoc Institute of Medicine committee will develop a report with recommendations for policies to improve graduate medical education (GME), with an emphasis on the training of physicians. Specific attention will be given to increasing the capacity of the nation’s clinical workforce that can deliver efficient and high-quality health care that will meet the needs of our diverse population. To that aim, in developing its recommendations the committee will consider the current financing and governance structures of GME; the residency pipeline; the geographic distribution of generalist and specialist clinicians; types of training sites; relevant federal statutes and regulations; and the respective roles of safety net providers, community health/teaching health centers, and academic health centers.

physician assistant education; management of health care systems; GME programs in teaching hospitals, VA facilities, rural areas, safety net institutions, and teaching health centers; Medicare and Medicaid GME financing; GME accreditation and certification; and health and labor economics. The committee also included a consumer representative and a recent GME graduate.

The committee recognized that improving the governance and financing of GME cannot, on its own, produce a high-value, high-performance health care system. Other factors, such as the way in which we pay for health care services, are far more significant. Nevertheless, the GME system is a powerful influence on the makeup, skills, and knowledge of the physician workforce.

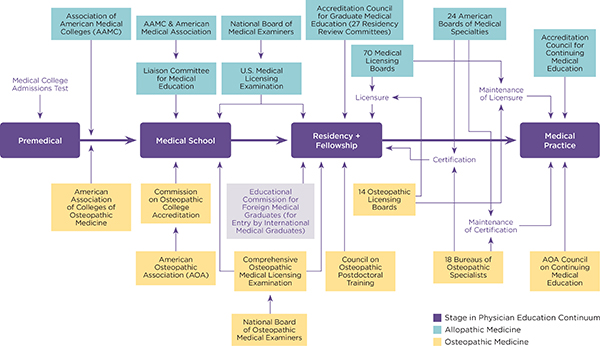

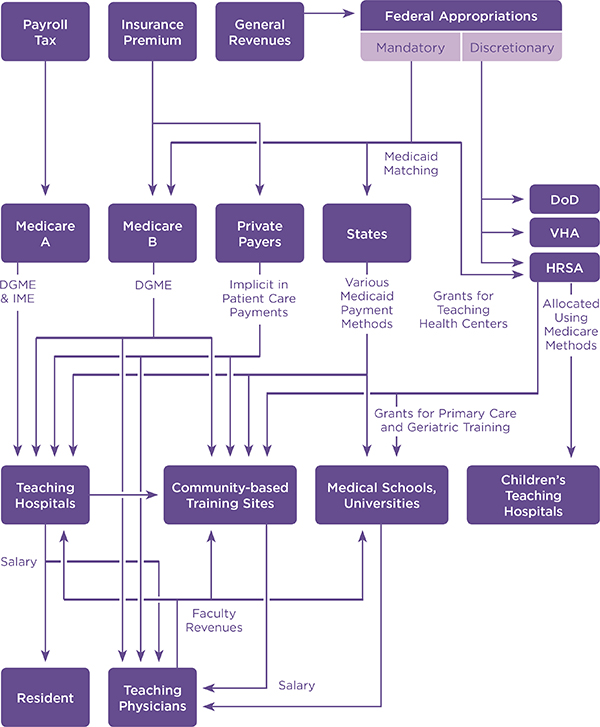

Thus, the overarching question in this report is, To what extent is the current GME system producing an appropriately balanced physician workforce ready to provide high-quality, patient-centered, and affordable health care? Answering this question is a formidable challenge. As Figures S-1 and S-2 illustrate, the financing and governance of the GME enterprise are exceedingly complex, involving numerous public and private organizations with independent standards and processes. Teasing out the dynamics of the system is difficult because so few financial, programmatic, and outcomes data are available. In addition, the data that are available are often incomplete and not comparable.

Ideally, GME policy should be considered in the context of the educational continuum, including premedical education, “undergraduate” (medical school) education, the residency and fellowship training that comprises GME, and continuing medical education after entry into practice. Although a comprehensive review of the full arc of medical education is needed, it is beyond the scope of this study.

Goals for Developing Policy Recommendations for the Future of GME

The committee began its deliberations by considering several fundamental questions: Should the public continue to support GME? If yes, why should Medicare, a health insurance program for older adults and certain disabled persons, fund an educational program? Would other GME financing mechanisms be more appropriate?

The committee debated—at great length—the justification and rationale for federal funding of GME either through Medicare or other sources, given the lack of comparable federal financing for undergraduate medical education, other health care professions, or other areas important to society

FIGURE S-1 Current flow of GME funds.

NOTE: DGME = direct graduate medical education; DoD = Department of Defense; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; IME = indirect medical education.

SOURCE: Adapted from Wynn, 2012 (Committee of Interns and Residents Policy and Education Initiative White Paper, “Implementing the 2009 Institute of Medicine recommendations on resident physician work hours, supervision, and safety”).

and in short supply. The committee recognized that both the public’s health and the economy have an important stake in the effectiveness and availability of the physician workforce and the health workforce overall. Moreover, the health care delivery system is in the midst of significant change as it moves toward a focus on achieving the triple aim of improving individual care, improving population health, and lowering costs (an aim for which the IOM has consistently advocated).

The committee concluded that leveraging the public’s GME investment for greater public benefit depends on secure and predictable funding. This goal is achievable by keeping federal GME support in Medicare, where it can continue as an entitlement program. Effective strategic investment is far less feasible in a federal program subject to annual discretionary funding. Thus, the committee decided to focus its recommendations on Medicare GME payment reforms (and their related governance), rather than on a broader array of policy alternatives, such as an all-payer GME system or a wholly new federal GME program.

As it began its assessment, the committee developed a set of goals (presented in Box S-2) to guide the development of its recommendations.

BOX S–2

IOM Committee’s Goals for Developing Graduate Medical Education (GME) Policy Recommendations

- Encourage production of a physician workforce better prepared to work in, help lead, and continually improve an evolving health care delivery system that can provide better individual care, better population health, and lower cost.

- Encourage innovation in the structures, locations, and designs of GME programs to better achieve Goal #1.

- Provide transparency and accountability of GME programs, with respect to the stewardship of public funding and the achievement of GME goals.

- Clarify and strengthen public policy planning and oversight of GME with respect to the use of public funds and the achievement of goals for the investment of those funds.

- Ensure rational, efficient, and effective use of public funds for GME in order to maximize the value of this public investment.

- Mitigate unwanted and unintended negative effects of planned transitions in GME funding methods.

THE OUTCOMES OF CURRENT GME GOVERNANCE AND FINANCING

Physician Workforce

Although the committee was not charged with projecting the future demand for physicians, it reviewed recent projections and analyses of the capacity of the physician workforce to meet the nation’s health needs. Some projections suggest imminent physician shortages that could prevent many people from getting needed health services. These analyses raise concerns that the rapid aging of the population and the expansion in health coverage resulting from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act3 will fuel demand for physician services far beyond the current capacity. However, the underlying methodologies and assumptions about the future in these studies are problematic. They generally assume historical provider–patient ratios using existing technological supports and thus have limited relevance to future health care delivery systems or to the need for a more coordinated, affordable, and patient-centered health care system.

Physician workforce analyses that consider the potential impact of changes and improvements in health care delivery draw different conclusions. These studies suggest that an expanded primary care role for physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses, redesign of care delivery, and the use of other innovations, such as telehealth and electronic communication, may ultimately lessen the demand for physicians despite the added pressures of the aging population and coverage expansions.

Some stakeholders and policy makers are pushing for significant increases in Medicare GME funding (via an increase in the cap on Medicare-funded residency positions) to ensure the production of more physicians. The available evidence, however, suggests that producing more physicians is not dependent on additional federal funding. The capacity of both medical schools and GME programs has grown considerably during the past decade. Between 2002 and 2012, overall enrollment in U.S. medical schools rose by nearly 28 percent, increasing from 80,180 to 102,498 students. In 2012, 117,717 physicians were in residency training—17.5 percent more than 10 years earlier.

Further increasing the number of physicians is unlikely to resolve workforce shortages in the regions of the country where shortages are most acute and is also unlikely to ensure a sufficient number of providers in all specialties and care settings. Although the GME system has been producing more physicians, it has not produced an increasing proportion of physicians who choose to practice primary care, to provide care to underserved popula-

________________

3 Public Law 111-148.

tions, or to locate in rural or other underserved areas. In addition, nearly all GME training occurs in hospitals—even for primary care residencies—in spite of the fact that most physicians will ultimately spend much of their careers in ambulatory, community-based settings.

There is worrisome evidence that newly trained physicians in some specialties have difficulty performing simple office-based procedures and managing routine conditions. In addition, medical educators report that GME curriculums lack sufficient emphasis on care coordination, team-based care, costs of care, health information technology, cultural competence, and quality improvement—competencies that are essential to contemporary medical practice. Recent surveys of residents and faculty suggest that they know little about the costs of diagnostic procedures and that residents feel unprepared to provide culturally competent care. It is noteworthy that the accrediting bodies for both allopathic and osteopathic medicine—the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Osteopathic Association, respectively—are currently remodeling their accreditation systems, in part to better prepare physicians for practice in the rapidly evolving U.S. health care system. The financial incentives in GME funding should reflect similar objectives.

Unintended Consequences of Medicare GME Payment Methods

The financial underpinnings of the GME enterprise are complex and largely undocumented. The committee found few informative data on GME financing and its outcomes. Medicare has minimal reporting requirements; teaching hospitals are asked to report only the data elements that are needed to calculate GME payments. Reported data on the direct costs of GME are not complete, standardized, or audited. Medicaid GME funding is especially opaque. The revenue impact and cost savings associated with sponsoring residents are neither tracked nor reported, and they are rarely acknowledged in analyses of GME costs. As a result, the financial impact of residency training programs on teaching hospitals and other sponsoring organizations is not well understood.

Federal funding for GME includes both mandatory (Medicare and the federal Medicaid match) and discretionary appropriations (HRSA, VA, and U.S. Department of Defense). Most states support GME through their Medicaid programs, and some states provide other GME support through state-based programs. Hospitals, universities, physicians’ organizations, and faculty practice plans also support residencies and fellowships. Private GME funding—philanthropy and gifts or grants from industry—is not well documented, but it may be significant. Private insurers support GME indirectly by paying higher rates to teaching hospitals.

The statutes governing Medicare’s GME financing were developed at a

time when hospitals were the central—if not exclusive—site for physician training. Medicare GME payment rules continue to reflect that era. GME monies are distributed directly and primarily to teaching hospitals, which in turn have fiduciary control over the funds. There are two independent Medicare funding streams:

- Direct graduate medical education (DGME) payments (based on costs in 1984-1985), intended to cover the salaries and benefits of residents and faculty and certain other costs; and

- An indirect medical education (IME) adjustment to Medicare prospective payment system (PPS) inpatient rates, aimed at helping to defray additional costs of providing patient care thought to be associated with sponsoring residency programs.

Both funding streams are directly tied to a hospital’s volume of Medicare inpatients. In 2012, IME accounted for $6.8 billion, or 70.8 percent, of total Medicare GME payments to teaching hospitals. DGME payments totaled $2.8 billion, or 29.2 percent.

In 1997, Congress capped the number of Medicare-supported physician training slots. Hospitals may add residents beyond the cap but cannot receive additional Medicare payments for those trainees. The cap is equal to each hospital’s number of residents in 1996—essentially freezing the geographic distribution of Medicare-supported residencies without regard for future changes in local or regional health workforce priorities or the geography and demography of the U.S. population. As a result, the highest density of Medicare-supported slots and Medicare GME funding remains in the Northeast.

By distributing funds directly to teaching hospitals, the Medicare payment system discourages physician training outside the hospital, in clinical settings where most health care is delivered. Linking GME payments to a hospital’s Medicare inpatient volume systematically disadvantages children’s hospitals, safety net hospitals, and other institutions that care for non-elderly patients. Non-clinical, population-based specialties, such as public health and preventive medicine, are similarly affected.

Stewardship of Public Funding

Common notions of good governance are based on the expectation that public programs have the capacity to ensure responsible stewardship of public funds, provide appropriate program oversight, and achieve defined program outcomes. Good governance also requires transparency—public access to information—to promote accountability. Because Medicare GME funding is formula-driven, the payments are essentially guaranteed

regardless of whether the funded trainees reflect local, national, or regional health needs. The system’s only mechanism for ensuring accountability is the requirement that residency programs be accredited. The system does not yield useful data on program outcomes and performance. There is no mechanism for tying payments to the workforce needs of the health care delivery system. There is also no requirement that, after graduation from a Medicare- or Medicaid-supported residency program, physicians accept or provide services to Medicare or Medicaid patients.

Significant reforms are needed to ensure that the public’s sizeable investment in GME is aligned with the health needs of the nation. Because the rules governing the Medicare GME financing system are rooted in statute, these recommended reforms, presented below, cannot occur without legislative action. The committee strongly urges Congress to amend Medicare law and regulation to begin the transition to a performance-based system of Medicare GME funding.

The committee’s recommendations provide an initial roadmap for reforming the Medicare GME payment system and building an infrastructure to drive strategic investment in the nation’s physician workforce. The recommendations call for substantial change in how Medicare GME funds are allocated and distributed.

As outlined below and detailed in Chapter 5, the committee proposes to maintain level GME funding from Medicare (updated for inflation), with funds separately distributed for two purposes: operational (supporting continuation of current GME programs) and transformational (supporting innovation and planning for the future). The relative amounts allocated for these purposes will need to shift over time. Transformational funds will support work to develop a foundation for a performance-based GME payment methodology, which represents a central aim of these recommendations.

The committee acknowledges that repurposing and redesigning GME funding will be disruptive for teaching hospitals and other GME sponsors accustomed to receiving Medicare GME monies in roughly the same way for nearly 50 years. Change cannot and should not occur overnight; training organizations will need to minimize disruption to patient care delivery, honor multiyear commitments to trainees, and renegotiate existing contractual arrangements with affiliated training organizations. The committee recommends a phased implementation over a 10-year period. The ongoing need for Medicare GME funding should then be reassessed. The committee’s guidance for this transition is included in Chapter 5.

Although clearly far-reaching and a marked change from the status quo, the committee’s recommendations are based on careful consideration

of available evidence on the outcomes and unintended consequences of the current GME financing system. The recommendations are also based on the fundamentals of good governance, particularly transparency and accountability to the public for program outcomes. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has successfully accomplished major payment transitions before—during implementation of the Medicare PPS in the 1980s and the Medicare Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) payment system in the 1990s. Both the PPS and RBRVS reforms involved far greater percentages of Medicare spending.

Transforming Medicare’s role in GME financing will be a complex undertaking requiring careful planning. The committee’s recommendations outline objectives for the transition and provide building blocks for a reformed, value-based Medicare GME financing program. A well-resourced program infrastructure should be established quickly to formulate a more detailed roadmap than the one presented here.

Invest Strategically

At a time when all federal programs are under close scrutiny and the return on the public’s investment in GME is poorly understood, the committee cannot support maintaining Medicare GME funding at the current level without establishing a path toward realignment of the program’s incentives and a plan for documentation of outcomes. The continuation and appropriate level of funding should be reassessed after the implementation of these reforms.

RECOMMENDATION 1: Maintain Medicare graduate medical education (GME) support at the current aggregate amount (i.e., the total of indirect medical education and direct graduate medical education expenditures in an agreed-on base year, adjusted annually for inflation) while taking essential steps to modernize GME payment methods based on performance, to ensure program oversight and accountability, and to incentivize innovation in the content and financing of GME. The current Medicare GME payment system should be phased out.

Build an Infrastructure to Facilitate Strategic Investment

The committee urges Congress and the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to take immediate steps to establish a two-part governance infrastructure for federal GME financing. Transforming Medicare GME financing will require an overarching policy-development and decision-making body and a separate operations center to administer GME payment reforms and solicit and manage demonstrations of new

GME payment models. A portion of current GME monies should be allocated to create and sustain these new entities. No additional public funds should be used.

RECOMMENDATION 2: Build a graduate medical education (GME) policy and financing infrastructure.

- 2a. Create a GME Policy Council in the Office of the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Council members should be appointed by the Secretary and provided with sufficient funding, staff, and technical resources to fulfill the responsibilities listed below:

- Development and oversight of a strategic plan for Medicare GME financing;

- Research and policy development regarding the sufficiency, geographic distribution, and specialty configuration of the physician workforce;

- Development of future federal policies concerning the distribution and use of Medicare GME funds;

- Convening, coordinating, and promoting collaboration between and among federal agencies and private accreditation and certification organizations; and

- Provision of annual progress reports to Congress and the Executive Branch on the state of GME.

- 2b. Establish a GME Center within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services with the following responsibilities in accordance with and fully responsive to the ongoing guidance of the GME Policy Council:

- Management of the operational aspects of GME Medicare funding;

- Management of the GME Transformation Fund (see Recommendation 3), including solicitation and oversight of demonstrations; and

- Data collection and detailed reporting to ensure transparency in the distribution and use of Medicare GME funds.

Establish a Two-Part Medicare GME Fund

The committee recommends allocating Medicare GME funds to two distinct subsidiary funds:

- A GME Operational Fund to distribute per-resident amount payments directly to GME sponsoring organizations for approved Medicare-eligible training slots. The fund would finance ongoing residency training activities sponsored by teaching hospitals, GME consortiums, medical schools and universities, freestanding children’s hospitals, integrated health care delivery systems, community-based health centers, regional workforce consortiums, and other qualified entities that are accredited by the relevant organization. Under current rules, teaching hospitals sponsor nearly half (49.9 percent) of all residency programs, and slightly more than half of all residents (52.1 percent) train in programs sponsored by teaching hospitals.

- A GME Transformation Fund to finance new training slots (including pediatric residents currently supported by the Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education program and other priority slots identified by the GME Policy Council), to create and maintain the new infrastructure, to ensure adequate technical support for new and existing GME sponsoring organizations, to sponsor development of GME performance metrics, to solicit and fund large-scale GME payment demonstrations and innovation pilots, and to support other priorities identified by the GME Policy Council.

RECOMMENDATION 3: Create one Medicare graduate medical education (GME) fund with two subsidiary funds:

- 3a. A GME Operational Fund to distribute ongoing support for residency training positions that are currently approved and funded.

- 3b. A GME Transformation Fund to finance initiatives to develop and evaluate innovative GME programs, to determine and validate appropriate GME performance measures, to pilot alternative GME payment methods, and to award new Medicare-funded GME training positions in priority disciplines and geographic areas.

The committee expects that the GME Transformation Fund will provide the single most important dynamic force for change. Box S-3 provides preliminary guidance for the fund’s organization and ongoing operations. All GME sponsor organizations should be eligible to compete for both innovation grants and additional funding for new training positions.

One of the key elements of the IOM committee’s recommendations is the creation of a graduate medical education (GME) Transformation Fund to finance demonstrations of innovative GME payment methods and other interventions to produce a physician workforce in sync with local, regional, and national health needs. All GME sponsor organizations should be eligible to compete for innovation grants. The committee recommends that the fund’s organization and ongoing operations be based on the following principles.

- Goal of the program: to support physician and other health professional education toward achievement of the “triple aim,” that is, improving the individual experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per-capita costs of care

- Four operational principles

- – Speed and efficiency

- – Measurability and evaluation

- – Sustainability

- – Scalability

- Identifying priority topics

- – Investigator- and program-initiated

- – Focus on national-, regional-, and state-level issues

- Potential questions for early Requests for Proposals

- – What are feasible and valid measures of training success?

- – What new models of financing might better achieve the triple aim?

- – Voucher systems?

- – Differential per-resident amounts?

- – Allowing institutions to bill third parties for certain residents’ services?

- – What interventions work best to increase the racial and ethnic diversity of the physician workforce? To improve physicians’ cultural competence?

- – What models of interprofessional training—including physician assistants, advanced practice registered nurses, and other clinicians—better prepare physicians for team-based practice and care delivery in community settings?

- – Should GME funds be used for advanced training in other disciplines, for example, physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses?

- – How might training or training funding expand across the physician education continuum (from undergraduate to GME to continuing medical education) to maximize efficiency?

- – How might GME training programs be streamlined, for example, reducing training time through earlier specialization or other mechanisms?

- “Innovation innovation,” that is, attention to scalability in projects to learn what is required to achieve innovation in real-world programs

Modernize Medicare GME Payment Methodology

The purchasing power of Medicare GME funding provides a significant opportunity for strategic investment in the physician workforce. The separate IME and DGME funding streams, however, present a formidable obstacle to taking advantage of this opportunity. Maintaining separate IME and DGME funding streams would hamper efforts to collect and report standardized data, to link payments with program outcomes, to reduce geographic inequities in GME payments, and to minimize administrative burden. Separate funding streams create unnecessary complexity, and there is no ongoing rationale for linking GME funding to Medicare patient volume because GME trainees and graduates care for all population groups. Finally, basing payment on historical allocations of DGME costs and training slots only prolongs the current inequities in the distribution of GME monies.

RECOMMENDATION 4: Modernize Medicare graduate medical education (GME) payment methodology.

- 4a. Replace the separate indirect medical education and direct GME funding streams with one payment to organizations sponsoring GME programs, based on a national per-resident amount (PRA) (with a geographic adjustment).

- 4b. Set the PRA to equal the total value of the GME Operational Fund divided by the current number of full-time equivalent Medicare-funded training slots.

- 4c. Redirect the funding stream so that GME operational funds are distributed directly to GME sponsoring organizations.

- 4d. Implement performance-based payments using information from Transformation Fund pilot payments.

Medicare’s current GME payment mechanisms should be replaced with a method that provides a pathway to performance-based GME financing. This transition should be phased in and carefully planned under the guidance of the GME Policy Council, in consultation with the CMS GME Center and GME stakeholders. The Policy Council should ensure that its blueprint for the transition includes a rigorous strategy for evaluating its impact and making adjustments as needed.

Medicaid GME

Information on Medicaid GME programs is scarce, and on Medicaid GME funds flow, it is particularly opaque. The committee was not able to conduct an in-depth assessment of Medicaid-funded GME. Nevertheless,

as a multibillion-dollar public investment ($3.9 billion in fiscal year 2012), the public has the right to expect basic transparency and accountability in Medicaid GME funding. As Chapter 3 describes, there is little evidence that states use Medicaid GME funds to achieve policy objectives (despite concerns about physician shortages). The committee suggests that the GME Policy Council consider the extent to which it might advise the CMS Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services and the state Medicaid programs on introducing transparency in their GME programs.

RECOMMENDATION 5: Medicaid graduate medical education (GME) funding should remain at the state’s discretion. However, Congress should mandate the same level of transparency and accountability in Medicaid GME as it will require under the changes in Medicare GME herein proposed.

CONCLUSION

The committee recommends that continued Medicare support for GME be contingent on its demonstrated value and contribution to the nation’s health needs. Under the current terms of GME financing, there is a striking absence of transparency and accountability for producing the types of physicians that today’s health care system requires. Moreover, newly trained physicians, who benefit from Medicare and Medicaid funding, have no obligation to practice in specialties and geographic areas where they are needed or to accept Medicare or Medicaid patients once they enter practice.

In conclusion, the committee recommends that Medicare GME funding be leveraged toward the achievement of national health care objectives. Continued federal funding should be delivered by a system that ensures transparency and accountability for producing a workforce suited to the needs of the health care system. The committee recognizes that reforming GME and its governance and financing cannot—on its own—produce a high-value, high-performance health care system. However, appropriate preparation of the physician workforce is an essential component of this transformation. The recommendations presented in this report provide a roadmap to this end.