Appendix C

A Prescription Is Not Enough: Improving Public Health with Health Literacy1

Andrew Pleasant, Ph.D.,a Jennifer Cabe, M.A.,a Laurie Martin, Sc.D., M.P.H.,b and R. V. Rikard, Ph.D.c

Commissioned by the

Institute of Medicine

Roundtable on Health Literacy

a Canyon Ranch Institute, Tucson, AZ 85750, http://www.canyonranchinstitute.org.

b RAND Corporation, Arlington, VA 22202, http://www.rand.org.

c North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, http://www.ncsu.edu.

_______________

1 The authors are responsible for the content of this article, which does not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Medicine.

CONTENTS

A Prescription Is Not Enough: Improving Public Health with Health Literacy

Brief Review of U.S. Public Health Key Indicators

The Fit Between Health Literacy and Public Health

Case Study: Louisiana—The Potential of Leveraging Public Health Institutes

Case Study: Nebraska—The Strength of Weak Ties

The Nebraska Public Health System

Health Literacy and Public Health in Nebraska

Case Study: Arkansas—Coordinated, Reasonable, and Reasoned Statewide Action

Public Health and Health Literacy: What’s Happening?

The Potential Utility of Health Literacy to Public Health

Conclusions and Recommendations

BOX

1 A Public Health Opportunity: Advancing Health Literacy in Jails and Prisons

FIGURES

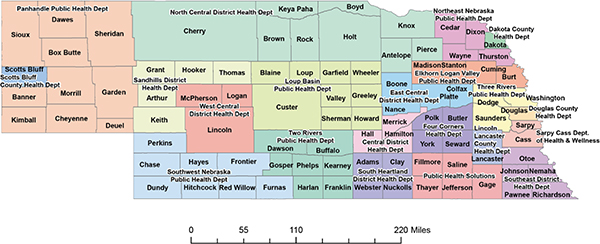

1 Public health departments in Nebraska

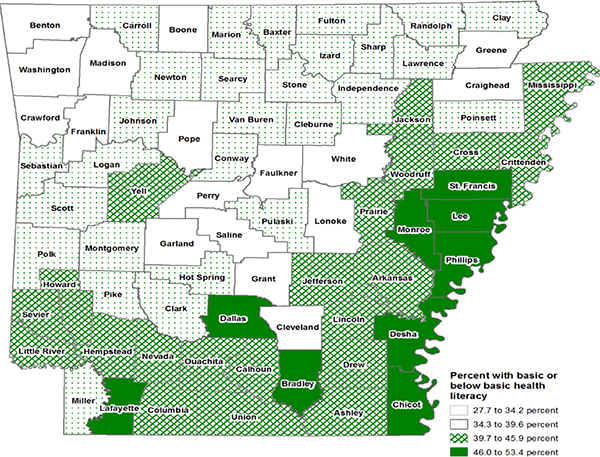

2 Percentage of Arkansas population with low health literacy

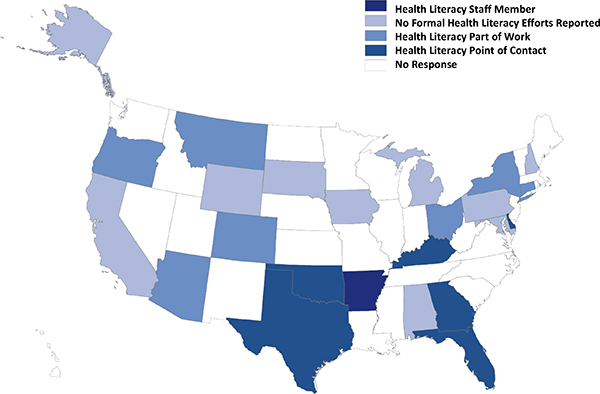

3 Health literacy within state departments of public health

4 “THIS IS PUBLIC HEALTH” campaign sticker

TABLES

1 Perceived Relevance of the 10 Attributes of a Health-Literate Organization

2 Health Literacy Activities Within Public Health Departments

This article would have never materialized without the support of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the members of the IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy. The authors collectively would like to thank the staff and members of the Roundtable for their tireless and continuing efforts to advance the field of health literacy. While we want to especially recognize the efforts of Lyla Hernandez, M.P.H., at the IOM, we also realize that no one who produces effective efforts works within a vacuum or without numerous sources of support. Thank you, all.

Andrew Pleasant extends a hearty hello and thank you to each of his colleagues at Canyon Ranch Institute. Their daily support and patience helped make this publication possible. Russell Newberg, M.P.A., coordinator at Canyon Ranch Institute, deserves a particular acknowledgment for his assistance in contacting state departments of health. Andrew also would like to extend a special thank you to all of the coauthors of this article. No one knows as well as they do how impossible this effort would have been to accomplish without their support and dedication. As a quick aside, team efforts like this reinforce the need for a new approach to equitably listing coauthors. All Andrew can say is—“Thank you, Jennifer, Laurie, and R. V.!”

Robert Vann (R. V.) Rikard would like to thank the IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy staff and members for their courage and compassion in addressing the health inequities of low health literacy and poor health. R. V. would also like to thank the numerous and far-flung Nebraska public health planners and practitioners who spoke with him for the case study in this article focused on Nebraska. R. V. wants to mention that the Nebraska case study would not have been possible without the collaboration of Susan Bockrath, M.P.H., CHES, health literacy consultant and project director for the Nebraska Association of Local Health Directors’ Outreach Partnership to Improve Health Literacy. R. V. would also like to express his gratitude to the personnel from public health agencies in Nebraska and many other states who provided their insights in the online survey. Last but certainly not least, R. V. wishes to thank Dr. Andrew Pleasant for sharing the opportunity to develop this important article; for leading so many other meaningful efforts in health literacy research, practice, and policy; and for being a friend and mentor.

Jennifer Cabe would like to thank Dr. Andrew Pleasant for including her and the entire Canyon Ranch Institute team in his groundbreaking research and thought leadership in the fields of health literacy and public health. For all of Andrew’s admirable qualities and successes, we most appreciate his unwavering dedication to our shared mission to educate, inspire, and empower all people to embrace a life of wellness. Jennifer would also like

to express a world of thanks to Jennifer Dillaha, M.D., medical advisor for health literacy and communication for the Arkansas Department of Health, for facilitating connections to the work of the Department. Any government health endeavor would benefit from Dr. Dillaha’s knowledgeable and collaborative approach to getting the job done. On behalf of the Cabe family of Arkansas, led by our grandparents Raymond and Alice V. Cabe, Jennifer would like to express deep appreciation for the ongoing efforts across Arkansas to advance health literacy and improve the health of individuals and communities. Finally, Jennifer would like to thank her colleagues from the Office of the Surgeon General who served during the term of 17th U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Richard H. Carmona. They helped move forward the understanding and use of health literacy as a catalyst for improving public health—both nationally and globally—in countless innovative ways. Thanks are especially due in this regard to Surgeon General Carmona, Deputy Surgeon General Kenneth P. Moritsugu, Chief of Staff Robert Williams, Communications Director Craig Stevens, and Jennifer’s fellow speechwriters Leanne Boyer and Monique LaRocque.

Laurie Martin would like to thank the many public health practitioners from Louisiana who took the time to participate in the discussions that led to the case study focused on Louisiana. Laurie would also like to thank the personnel from public health agencies who provided their insights in the online survey that was developed and widely disseminated by the authors.

A PRESCRIPTION IS NOT ENOUGH: IMPROVING PUBLIC HEALTH WITH HEALTH LITERACY

Health literacy is always present, but too often neglected. This article focuses on the use—and the lack of use—of health literacy within efforts to address public health in the United States. In particular, this article focuses on efforts within state, local, tribal, and territorial public health organizations. Overall, while a growing body of evidence strongly suggests that health literacy can be effective in public health when explicitly addressed, the concept and associated best practices of health literacy do not seem to be consistently or universally used within public health organizations. As a result, the effectiveness of public health efforts is reduced and public health suffers.

Successfully integrating the best practices and knowledge of health literacy into public health practice is likely the most significant opportunity that currently exists to improve individual, community, and public health.

The overall body of evidence regarding health literacy has clearly advanced to the point where it is logically impossible to conceive of a situation wherein health literacy is not at least a partial determinant of public health status. More likely, as more and stronger evidence is clearly war-

ranted, health literacy is among the strongest determinants of public health in the United States.

A practical corollary of that observation is that health literacy should be an explicit component of the design of all public health interventions and robustly embedded within the structure and function of public health organizations. Neither of those attributes seems to be the case universally in the vast majority of public health organizations at this point in time across the United States. Exceptions do exist, and this article explores three examples through a case study approach.

In 2000, nearly 14 years ago, Donald Nutbeam wrote as the first line of an article proposing that health literacy is an explicit goal of public health, but “health literacy is a relatively new concept in health promotion” (Nutbeam, 2000). Health literacy is no longer a new idea in health promotion, public health, or clinical practice. However, the uptake of health literacy into actual application through organizational structure and daily practice remains in its infancy. Perhaps efforts like the recent paper by Brach and colleagues (2012) focusing on the attributes of a health-literate organization will have a positive effect on this situation.

However, as this article will illustrate, public health departments currently seem not to be universally or explicitly addressing health literacy. IOM reports focused on public health, such as the recently released U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health, also fail to explicitly mention health literacy. Although the content of that report makes the importance of health literacy exceeding clear, health literacy as an approach to improving public health is not explicitly addressed (NRC and IOM, 2013).

In 2006, a report about the U.S. Surgeon General’s Workshop on Improving Health Literacy concluded with several observations from then-Acting Surgeon General Kenneth Moritsugu:

First, that we must provide clear, understandable, science-based health information to the American people. In the absence of clear communication and access, we cannot expect people to adopt the health behaviors we champion. Second, the promises of medical research, health information technology, and advances in healthcare delivery cannot be realized if we do not simultaneously address health literacy. Third, we need to look at health literacy in the context of large systems—social systems, cultural systems, education systems, and the public health system. Limited health literacy is not an individual deficit but a systematic problem that should be addressed by ensuring that healthcare and health information systems are aligned with the needs of the public and with healthcare providers. Lastly, more research is needed. But there is already enough good information that we can use to make practical improvements in health literacy. (Office of the Surgeon General, 2006)

Now, 8 years later, those four recommendations, by and large, remain unfulfilled. What we know is possible through the limited yet growing body of research on health literacy is still not being put into place in the United States. Other work indicates that the United States remains ahead of much, but not all, of the world in regard to putting health literacy research into practice. However, were data sufficient, that difference would likely not be statistically significant (Pleasant, 2013a,b).

For example, health literacy can, and should, inform the redesign of health systems in order to produce both savings in costs and improvements in health outcomes—yet the public health system has by and large not embarked on that effort. Some clinical care systems have begun that process (Pleasant, 2013a,b). In fact, efforts to improve the design and function of the U.S. health system continue to meet uninformed resistance reflecting political interests rather than the interest of public health.

Regardless of the underpinnings of any individual or institutional resistance to embracing the best practices of health literacy in public health efforts, the overarching reality is that the time is ripe for the field of health literacy to increasingly engage with public health efforts. Every indication is that now is an opportune time to fully realize the potential of health literacy to lower costs while improving the overall health and well-being of the U.S. population.

Although more research is certainly needed, we now have 8 more years of research since the Surgeon General’s Workshop on Improving Health Literacy. That research indicates more explicitly and robustly that public health efforts need to engage with the field of health literacy in order to effectively and efficiently reach the mutual goal of a healthy public.

“Health literacy” has been variously defined by different perspectives at different times. The presence or absence of public health within those definitions is, in fact, one of the bases for critical analysis of those varying definitions.

For instance, the most cited definition within the United States to date is the definition proposed in the IOM’s initial report on health literacy that was published in 2004 (IOM, 2004). That volume, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion, used the definition presented by the National Library of Medicine and also used in Healthy People 2010 and 2020 efforts (Selden et al., 2000). That approach defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”

While neither the first IOM report on health literacy nor the defini-

tion of health literacy put forth in that volume exclude public health, they also do not explicitly embrace public health. There is not a chapter in the volume explicitly focused on public health applications of health literacy. There are chapters about defining the concept of health literacy, the extent and associations of limited health literacy, culture and society, educational systems, and health systems—but nothing squarely focused on public health.

What is also missing from that definition is an explicit acknowledgment that successful outcomes from health literacy result from both the supply of behavioral skills of individuals as well as the demand for those skills that is created by the U.S. health care system. The focus of that definition is also solely on the individual. There is no reference to sharing capacity across families, communities, or other social groupings—an important consideration in public health. There is no true reference to the abilities of individuals to navigate systems—another important consideration in public health.

The phrase “public health” appears only 46 times (excluding references) in that 345-page volume. By comparison, the combined use of the words “doctor” and “physician” roughly double that count. The word “hospital” appears nearly twice as often as “public health” and the word “medicine” appears roughly three times as frequently throughout the text. The phrase “public health” does not appear in the index of the volume. Further examples, illustrating perhaps not the explicit focus but the implicit emphasis of the volume, include “Medical Expenditure Panel Survey” with three entries reported in the Index, “Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations” with five entries, and “National Committee for Quality Assurance” with six entries.2 Overall, the volume is framed largely to focus on the clinical, versus public health, context. This is true from the very beginning of the volume as the title explicitly states that a prescription is needed versus—in the common parlance of public health—a program.

One small effort that has moved toward a more explicit inclusion of public health within a definition of health literacy is the Calgary Charter on Health Literacy. The Charter is a freely accessible result of an international effort to advance health literacy that offers all interested parties a chance to perform their own peer review and sign on to the Charter at http://www.centreforliteracy.qc.ca/health_literacy/calgary_charter. The definition of health literacy that the Charter proposes is a testable model of health

_______________

2 For comparison purposes, the 1988 National Academy Press publication titled The Future of Public Health does not contain the word “literacy” or the phrase “health literacy.” In the 2013 National Academies Press publication titled Public Health Linkages with Sustainability: Workshop Summary, the phrase “health literacy” appears three times. Progress is slow, but it is occurring.

literacy that can produce successful outcomes of the relationship between the supply and demand of health literacy that is central to public and individual health (Coleman et al., 2009). This approach is as much about what people do with the set of behavioral skills that support their health literacy as it is about the level of those skills they may possess. This definition clearly indicates that health professionals can help the public to (or the public at various skill levels can) achieve positive health outcomes by directing the skills they do possess to find, understand, evaluate, communicate, and use information to make informed decisions about their health.

The Calgary Charter formally defines health literacy as “health literacy allows the public and personnel working in all health-related contexts to find, understand, evaluate, communicate, and use information. Health literacy is the use of a wide range of skills that improve the ability of people to act on information in order to live healthier lives. These skills include reading, writing, listening, speaking, numeracy, and critical analysis, as well as communication and interaction skills” (Coleman et al., 2009).

That approach lays out a model of health literacy more in the mode of a theory of behavior change than a label that hopes to aggregate a broad set of skills and abilities. Health literacy, and literacy, are behaviors. Thus, behavior change is the outcome of improved health literacy. Behavior change is a highly targeted and valued outcome in public health efforts as well.

Research by many scholars makes it precisely clear that health literacy interventions must include a keen awareness of fundamental literacy, scientific literacy, cultural literacy, and civic literacy. That essential truth could not be more necessary than in efforts to improve public health. In fact, if the language fails, if the effort is not evidence based, if culture is not considered, or if people are not engaged and empowered, then interventions will fail to improve public health (Zarcadoolas et al., 2006).

Although health literacy is a relatively new concept, the idea of public health has a much longer history. In 1920, C. E. Winslow offered one of the earliest definitions of public health, which is still among the most frequently cited today, yet has essentially not been addressed within the literature on health literacy (IOM, 1988). Winslow’s definition posits that “public health is the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health and efficiency through the organized community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing services for the early diagnosis and preventive treatment of disease, and the development of social machinery which will

ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health” (Winslow, 1920b).

In that same year, Winslow also offered a comparable, yet slightly different, definition of public health as “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities, and individuals” (Winslow, 1920a).

While both definitions clearly assert the need for an organized effort, the second definition introduces the need for an informed choice and a range of levels—from the individual to society—wherein that informed choice may occur. That, as discussed earlier in this article, extends beyond the most cited definition of health literacy to date, which maintains a sole focus on the individual and an “appropriate” choice.

Winslow also asserted, more than 90 years ago, that “the public health campaign of the present day has become preeminently an educational campaign. There are those who maintain that because the public health authority alone possesses the power to enforce regulations with the strong arm of the law such authorities should confine themselves to the exercise of police power, leaving educational activities to develop under the hands of private agencies. The actual amount of lifesaving that can be accomplished by purely restrictive methods is, however, small, and such exercise of police power as may be necessary can only gain in effectiveness if it forms an integral part of a general campaign of leadership in hygienic living” (Winslow, 1920b, p. 26). It seems that an early pioneer in defining public health depicted a stronger role for health literacy than current public health organizations do today.

That tension Winslow described nearly 100 years ago—between an educational effort eliciting voluntary participation and a top-down regulatory effort—remains at much of the forefront of public health today. Perhaps the most current manifestation of that debate emerged recently with then-New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg proposing a ban on carbonated beverages greater than 16 ounces in size at restaurants, theaters, and food carts.

Health literacy, it is worth noting, can provide an effective resolution to that ongoing debate. Given Winslow’s preference for what he termed educational versus “restrictive methods,” it seems relatively safe to assume he would agree with that proposition. The critical difference, and one that seems safe to assume Winslow would approve of, is that health literacy poses the outcome of an engaged individual empowered to make well-informed decisions about health whereas regulation poses the outcome of a compliant individual.

Nearly 70 years after Winslow penned his definitions of public health, the IOM published The Future of Public Health, which defined public

health as an “organized community effort to address the public interest in health by applying scientific and technical knowledge to prevent disease and promote health” (IOM, 1988, p. 7). The passage of nearly a century seems to have not withered the usefulness and appropriateness of much of Winslow’s definitions of public health. Health literacy, in comparison, seems to be in a pre-Winslow stage in regard to the development of a broadly accepted and used formal definition.

Another overlap is worthy of mention between Winslow’s approach to public health and current approaches to health literacy. As Roter and colleagues (2001) noted, “Winslow, an advocate for public education as early as the 1890s, maintained: ‘the discovery of popular education as an instrument of preventive medicine, made by the pioneers in the tuberculosis movement, has proved almost as far-reaching in its results as the discovery of the germ theory of disease thirty years before.’”

If there is a “golden rule” to health literacy, it is to involve people early and often in their own health. That means health professionals will engage with the whole person, versus just diagnosing and treating a disease. Involving people early and often also inevitably shifts the focus to prevention rather than treatment of an illness after it manifests. Therefore, an emphasis on health literacy should inherently result in an emphasis on prevention. The early years of well-intentioned health literacy research that focused solely on clinical care settings were not wasted, but they were simply not based on an integrative approach to health that addressed the whole person’s life, intentions, and environment. Health literacy and, by extension, prevention is the missing gap in the design of the current U.S. “sick care” system where only a pittance of efforts focusing on prevention are reimbursable from insurers and governmental systems, which spend the majority of their efforts and funds (and thus creation of potential profits) on “sick care” rather than on promoting health and preventing disease, disability, and early death.

Prevention, health literacy, and reducing health care costs are integrally related. Ultimately, public health may be best differentiated from clinical medicine through the emphasis on prevention and targeting multiple social and environmental determinants of health versus a priority on treatment of the diagnosed individual (IOM, 1988). Collaboration and coordination between the two approaches is clearly necessary, but an appropriate balance is lacking in the United States and globally. Poor health literacy can be taken as one of many indicators of that imbalance.

Brief Review of U.S. Public Health Key Indicators

If the current state of public health in the United States is an indicator, and if the growing body of evidence regarding health literacy is not dis-

covered to be a false positive as methodologies continue to improve, much work remains to be accomplished in the field of health literacy. That work needs to be accomplished sooner rather than later as, according to a recent IOM report, the U.S. public health system and the state of public health in the country are not healthy. For example, the authors of this report (NRC and IOM, 2013) wrote that

- “The U.S. public health system is more fragmented than those in other countries” (p. 132).

- “Americans have had a shorter life expectancy than people in almost all of the peer countries. For example, as of 2007, U.S. males lived 3.7 fewer years than Swiss males and U.S. females lived 5.2 fewer years than Japanese females” (p. 2).

- “For decades, the United States has experienced the highest infant mortality rate of high-income countries and also ranks poorly on other birth outcomes, such as low birthweight. American children are less likely to live to age 5 than children in other high-income countries” (p. 2).

- “Deaths from motor vehicle crashes, non-transportation-related injuries, and violence occur at much higher rates in the United States than in other countries and are a leading cause of death in children, adolescents, and young adults” (p. 2).

- “Lung disease is more prevalent and associated with higher mortality in the United States than in the United Kingdom and other European countries” (p. 3).

- “Older U.S. adults report a higher prevalence of arthritis and activity limitations than their counterparts in the United Kingdom, other European countries, and Japan” (p. 3).

- “Childhood immunization coverage in the United States, although much improved in recent decades, is generally worse than in other high-income countries” (p. 118).

- “Since the 1990s, among high-income countries, U.S. adolescents have had the highest rate of pregnancies and are more likely to acquire sexually transmitted infections” (p. 2).

- “The United States has the second highest prevalence of HIV infection among the 17 peer countries and the highest incidence of AIDS” (p. 2).

- “Americans lose more years of life to alcohol and other drugs than people in peer countries, even when deaths from drunk driving are excluded” (p. 2).

- “For decades, the United States has had the highest obesity rate among high-income countries. High prevalence rates for obesity are seen in U.S. children and in every age group thereafter. From age

-

20 onward, U.S. adults have among the highest prevalence rates of diabetes (and high plasma glucose levels) among peer countries” (p. 3).

- “The U.S. death rate from ischemic heart disease is the second highest among the 17 peer countries” (p. 3).

- “Deaths and morbidity from non-communicable chronic diseases are higher in the United States than in peer countries” (p. 119).

Annually, three-quarters of U.S. health expenditures are spent on the treatment of chronic diseases—many of which are preventable (CDC, 2009). The United States spends more than 18 percent of our gross domestic product annually on sick care; 75 cents of every health care dollar is spent on treatment of chronic disease (CMS, 2011). Advancing health literacy to prevent disease and promote wellness is a proposition that is directly in line with the mission of public health organizations and has the added promise of not only improving health and well-being, but doing so at a lower overall cost over time.

The Fit Between Health Literacy and Public Health

The tools for public health efforts are traditionally limited to regulation, technology development, education, and persuasion. As discussed in this article, health literacy works to shift the emphasis toward the latter pair of education and persuasion versus technology and regulation. That is not to diminish the role of any, but to highlight the focus of health literacy. More importantly, health literacy may well be the best argument for the addition of engagement and/or empowerment as a core element of public health.

If there is one story to which all students of public health are exposed, it is the story of John Snow and the Broad Street water pump in London. This oft-told story of the “birth” of public health and epidemiology during a cholera outbreak in London in 1854 is largely focused on science-based regulation and top-down approaches. Snow took the data he had collected that supported his theory that a publicly accessible water pump was the source of cholera and city officials, begrudgingly, removed the handle from the water pump. As a result, the cholera epidemic was resolved.3

The core lesson of the story of John Snow and the Broad Street pump

_______________

3 An interesting aside: Some sources seem to so revere John Snow that he has been attributed with removing the pump handle himself rather than presenting his data (thus the birth of epidemiology specifically) to the Board of Guardians of St. James Parish. (In England, the parish is the first level of local government.) A majority of sources seem to agree that while the Board of Guardians is often described as being skeptical of Snow’s theory, they did order the pump handle removed.

handle is seemingly clear: Science-based regulation solves problems without public engagement or participation. However, it seems quite likely that the most frequent interpretation of the story is incomplete or at least somewhat misleading. Snow’s work would never have occurred without the participation of the hundreds of people he interviewed in order to develop his theory of how cholera was being spread through an unsafe water supply. While seldom (if ever) discussed in this manner, Snow’s work may also provide a first rough and incomplete example of community-based participatory research in a public health context. Snow clearly had to rely on the expertise of the public, including their health literacy skills, to help him to ascertain the relationship between the spread of cholera and use of the Broad Street water pump to obtain water.

At the individual level, just as John Snow did, public health efforts can target alone or in combination a person’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors by using a variety of tools ranging from regulation to education, persuasion, engagement—top-down and authoritative to community based and participatory. From that spectrum of possible public health targets, literacy is clearly a behavior. Reading, writing, and speaking are all behaviors. To make the much-discussed and -touted transition from learning to read to reading to learn is, in fact, a change in behavior. Thus, to improve literacy is to change behavior. Literacies are behaviors that people can perform at a wide range of skill levels. National surveys such as the National Adult Literacy Survey in 1994 and the National Assessment of Adult Literacy in 2004 clearly demonstrate that reality (Kirsch et al., 1993; Kutner et al., 2003).

As health literacy research and practice have developed over the past 20 years, it has become increasingly clear that few other factors have such a direct effect on an individual’s capacities to influence his or her own, family’s, and community’s health. However, from the founding stories of public health to efforts ongoing today, a tension exists between the tools of top-down regulation and bottom-up empowerment. This tension is also reflected in the structure and functioning of public health departments—which vary greatly in the United States. The following set of case studies illustrates how health literacy can be effectively put in place across that spectrum.

While the potential usefulness of health literacy to public health seems somewhat straightforward, what is not known is the extent to which, and how, public health organizations conceive of and operationalize health literacy; organize and train staff to address health literacy within their mission; and approach development of materials with health literacy in mind. The following components of this article—through a case study approach, reporting on evidence gathered through direct query to state departments of public health and an online inquiry of public health professionals, and an

analysis of selected public health efforts and situations—attempts to begin to answer those questions. (We describe each methodology further in the following sections.)

CASE STUDY: LOUISIANA—THE POTENTIAL OF LEVERAGING PUBLIC HEALTH INSTITUTES

Laurie Martin, Sc.D., M.P.H.

Across the nation, there are currently 37 Public Health Institutes (PHIs) and countless other organizations with the staff and expertise to support state and local public health departments. The goals and objectives of these Institutes vary, though some are proving to be valuable assets to public health departments’ efforts to address challenges related to low health literacy. This case study takes a closer look at a public health organization and a PHI in Louisiana, developed from a series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with staff at both institutions.

Participants at this public health organization in Louisiana report that health literacy is conceptualized as “the understanding of the target audience they are trying to reach.” This understanding is reported to include both the public and the providers who deliver services. There is a firm belief that health literacy efforts must involve all stakeholders. “It’s not just about ensuring that the public understands, but that those providing care are also paying attention to health literacy. The patient can ask all the questions they want, but if the provider is not on the same wavelength, they are never going to meet the patient’s needs.”

Programs within the public health organization are reported to have been taking a more proactive approach toward health literacy over the past 12 months. Staff are reported to be taking steps to make sure that messages they create are clearly communicated and that materials are written at an appropriate reading level. However, public health organization staff consistently noted that this is not always an easy task.

For example, a public health organization staff member reported that, “In Louisiana, we have a lot of different cultures that come into play when we are looking at health literacy, as well as age differences, races/ethnicities, rural versus urban differences … these factors make it more complicated … it’s not just about the piece of paper they are handed that tells them about their medicine—it can be in an easy-to-use format, but that doesn’t mean it’s understood. There are other barriers that may break that communication and understanding down.”

Public health organization staff participating in this case study process stated that they believed there was a need for additional health literacy

training across all health departments, and that such training should occur at the regional level. They noted the important role that public health organizations have in reaching out to vulnerable populations.

One participant at this public health organization in Louisiana said, “I think individual departments across the country could do a better job of educating the public, they are the boots on the ground, and they can take the time to make sure that patients understand. But just because you work in the field doesn’t mean that you can translate that knowledge to the public.”

The recognition that not all staff have been trained in health literacy has prompted some programs within the public health department in Louisiana to partner with the local Public Health Institute. PHI staff report using social marketing methodology to “develop messaging to meet consumers where they are—so it is meaningful and impactful.” Though not explicitly referred to as health literacy in the trainings, there is recognition among PHI staff that social marketing involves the basic principles of health literacy. Staff engage members of the target audience to help refine messaging and materials that are easy to understand and actionable, and disseminates those messages and materials in ways that are accessible. Public health department staff also believed that involving the target audience was an important lesson learned for public health agencies by noting that “[they] should be part of the development of what you are trying to create.”

The principles of social marketing, which overlap a number of health literacy best practices, have been successful for several joint projects between the public health organization and the PHI in Louisiana. In a recent tobacco control program, for example, the PHI developed a media campaign to promote cessation among pregnant smokers. Working closely with the target audience, they developed a media campaign that was understandable and actionable to pregnant women, resulting in a significant increase in the average call volume to the local smoking cessation quitline.

Staff at both the public health organization and the PHI noted that a significant barrier to implementing activities that addressed the challenges of low health literacy was the lack of a formal methodology for “how to do it.” With the exception of social marketing, staff at both the PHI and the state health department agreed with this participant’s view that, “To my knowledge, there is not a tried and true process for developing materials with this principle in mind. There’s that Word program that can tell you the reading level, but that has a lot of limitations. You may understand the basic tenets of health literacy, but without formal education or training, it is more a philosophy than a practical daily process or approach. To me, there’s a lack of a clear process or methodology that one’s expected to go through to meet the tenets of health literacy and make it part of a development process.”

Collectively, a perceived lack of easily accessible and transferable methodology and a lack of local and regional training opportunities, coupled with the fact that public health organizations are under the control of state or local governments, generate the perception that public health organizations serve more of a gatekeeper role; that is, they focus more on what is said (topics) than how it is said (health literacy). The participants in Louisiana expressed a clear recognition that health literacy is important across public health organizations and the PHI. They report there is positive movement in the amount of attention being paid to health literacy within those organizations as well. However, there is clearly room for improvement. Partnering with local PHIs, academics, or nonprofit organizations that focus on health literacy may promote synergistic efforts and help to fill some of the current gaps on these issues. Such partnerships may be particularly beneficial in the short term, as these organizations often are more nimble in their ability to hire qualified staff quickly and to spend necessary resources to ensure that the activities they produce are accessible, understandable, and actionable. Such partnerships, however, should not preclude development of internal capacity within public health organizations as it may also prove more efficient and cost-effective for those organizations to bring health literacy expertise into their staff over the longer term.

CASE STUDY: NEBRASKA—THE STRENGTH OF WEAK TIES

R. V. Rikard, Ph.D.

Nebraska’s sparse population density is a defining characteristic that shapes the public health system and the connection between public health and health literacy in the state.

There are a total of 77,421 square miles in the state of Nebraska, with a total population of 1,826,341 in 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Nebraska is the 43rd most populous state, with approximately 24 Nebraskans per square mile. For comparison, in Louisiana there are about 104 people per square mile while the New York City borough of Manhattan has more than 60,000 people per square mile.

This case study highlights the strength of Nebraska’s statewide decentralized public health system to address health literacy in Nebraska. Geographic distance does not seem to limit the “strength of weak ties” and shared commitment (Granovetter, 1973) of public health and health literacy professionals to address health literacy, reduce health disparities, and improve population-level health outcomes in the state.

This case study is based on a series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with the Nebraska Public Health Department staff, directors of local

public health departments or districts, and health literacy professionals. Background documents provided by Health Literacy Nebraska were also used.

The Nebraska Public Health System

Nebraska’s public health departments are diverse in terms of organization, funding streams, and services provided in their districts. While public health departments are a fairly new resource across Nebraska, public health and health literacy professionals recognize the important connection between public health and health literacy.

Prior to 2001, only 22 of Nebraska’s 93 counties were covered by a local health department or division. Legislative Bill 692, the Health Care Funding Act, was approved and enacted during the 2001 Legislative Session. The legislation directed Tobacco Master Settlement funds to support health-related activities in the state. As a result, all 93 of Nebraska’s counties are now covered by 21 local public health districts or departments (see Figure 1). The number of counties covered by a health district ranges from 1 to 10 depending on population density, and all provide a range of public health services.

In May 2012, the Nebraska Association of Local Health Directors (NALHD) secured grant funding through the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA’s) Rural Health Care Services Outreach Program. The grant funds the NALHD Outreach Partnership to Improve Health Literacy (OPIHL) by providing Nebraska’s public health workforce with technical assistance, training, and resources to address health literacy’s effect on the health of individuals and communities in Nebraska.

The program’s goals are fourfold over the 3-year funding period (2012-2015). The first is to delineate the health literacy education and training needs of Nebraska local and tribal health departments. The baseline survey results in 2012 revealed that participating health department staff had a need for increased knowledge and skills related to health literacy. Second, the baseline data guided the development and implementation of a comprehensive, evidence-based health literacy education and training program for local health department personnel. The third goal is to improve the health literacy of the rural populations participating in local health department programs by implementing tailored health literacy interventions that directly impact a specific population. The fourth, and ongoing, goal is to develop, disseminate, and promote a library of health literacy resources for all Nebraskans and other areas of the United States.

The participants interviewed for this case study pointed to the HRSA grant and OPIHL project as significant events that cemented the connection

between health literacy and public health in the Nebraska public health system.

Health Literacy and Public Health in Nebraska

The Steering Committee Chair for Health Literacy Nebraska provided contact information for many participants interviewed for this case study. A standard set of open-ended questions guided the interviews with participants, and the discussions lasted an average of 45 minutes. The semi-structured interview format allowed flexibility for the participant and the interviewer to have more of a conversation than a formal interview. Participant responses are summarized in the section below.

Regarding the definition of health literacy used, the majority of participants indicated that their health department defines health literacy as a means to communicate health information that the public will understand. However, the strongest theme in responses was not a focus on the inability of the public to understand health information; instead, the emphasis was placed on public health professionals not communicating information in a way that is understandable to the general public. Participants did not directly mention the IOM’s definition of health literacy; however, they noted that the most recognized health literacy definition is too narrow and does not provide the flexibility to tailor information to a specific audience.

Participants broadly agreed that health literacy is not a question of patients or public health professionals, as many participants expressly indicated they believed that health literacy is a shared responsibility for patients as well as public health and health care professionals—and that the professionals face a larger responsibility to make information understandable. For example, a participant pointed out that “health literacy is bidirectional—the work to be done is not on the patient side. The provider side needs to communicate in a way the general public understands.” One participant pointed out that the health care system in the United States focuses on disease and illness rather than prevention and promotion. Moreover, the participant pointed out that public health professionals are taking the leadership role to focus on health literacy as a means to prevention by stating, “public health is the ‘paper clip’ to hold all information together.”

In addition, participants provided examples of steps that their public health departments have taken to make health information understandable to the general public. Examples included improving signage at their public health department, upgrading and sharing easy-to-understand brochures, redesigning the department’s website, addressing the complexity of information regarding the Affordable Care Act and health insurance exchanges, and redesigning the health care system itself to try to reduce complexity.

Participants strongly indicated a widely shared view that health literacy

writer workshops, held in Nebraska as part of the HRSA grant, were valuable. In addition, access to and training to use the Health Literacy Advisor software reinforced the training from the health literacy writer workshops. A participant emphasized the importance of field-testing revised health information to ensure that the information was not so simple that it lost its usefulness to the public. Given that the OPIHL project is an ongoing initiative, participants noted that revising health information in their public health department is a primary focus at the current time. Yet, one participant pointed out a sustained public health department initiative by saying, “our health literacy project not only brought the language barriers to light, but we started a robust community health worker program as a result. We are now teaching a community health worker training course through a community college in Nebraska. It is a three-semester course and is the first in Nebraska.”

Reflecting on what health literacy best practices they might recommend to others, participants gave several pieces of advice primarily focused on public health organizations just beginning their efforts to address health literacy. One participant specifically stated, “You need a champion … bring in someone who has the health literacy knowledge base—someone who knows it, can teach it, and stays up to date on the literature.” Another participant said there is a need to have a revised definition of health literacy to guide public health agencies. Moreover, a revised definition requires consensus and engagement, specifically among national health policy leaders. Two participants mentioned the importance of attending a state or national health literacy conference such as the Institute for Healthcare Advancement (IHA) health literacy conference.

Another specific theme that emerged from the participants’ advice to other public health organizations is the importance of collaboration within and between public health agencies in the state as they begin their health literacy initiatives. According to the participants, this collaboration entails sharing documents and ideas, learning together, working together, and seeking out partnerships with other agencies/organizations.

In regard to what the field of health literacy could do to advance the role of health literacy in public health organizations, participants provided a clear message that they believed the best next step for the field of health literacy within public health is the creation of a health literacy organization. Such an organization should bring together interdisciplinary researchers to develop health literacy measures to determine if public health agencies are effectively reaching their communities. This type of organization, in participant’s views, could provide multiple publication venues for basic and applied research as well as evaluation of health literacy initiatives. Regional health literacy groups could provide an opportunity for collaboration among state agencies and provide access to expertise for public health

professionals who cannot afford to attend national conferences. Moreover, participants believed that a professional health literacy organization could gather and disseminate best practices and policies for public health agencies and practitioners. In sum, participants expressed their desire to form new ties with health literacy professionals in Nebraska, within regions, and across the United States.

CASE STUDY: ARKANSAS—COORDINATED, REASONABLE, AND REASONED STATEWIDE ACTION

Jennifer Cabe, M.A.

In June 2013, the Arkansas Department of Public Health issued a “State Health Assessment and State Health Improvement Plan” (hereafter referred to as “Assessment and Plan”). This case study relies heavily on that Assessment and Plan and on open-ended interviews with public health agency staff.

The Arkansas Department of Public Health does not provide a specific definition of health literacy, or refer to any definitions set forth by other organizations. Instead, this state’s health department describes health literacy through a conversational, even personal, tone. For example, the Assessment and Plan states: “Health literacy consists of a wide range of skills that people use to get and act on information so that they can live healthier lives. These skills involve reading, writing, listening, asking questions, doing math, and analyzing the facts.”

The Assessment and Plan also uses this conversational tone in describing the bidirectionality of health literacy: “Health literacy is also how well doctors, nurses, and other health care workers meet their patients’ needs and do it in a way that helps their patients know what they need to do to take care of themselves.”

The Arkansas Department of Public Health operates on the basis that low health literacy correlates with poor health. The state’s public health department staff members describe that poor health as being caused by both patient misunderstandings and health care system mistakes. The concept of bidirectional responsibility for health literacy is frequently echoed in conversations with public health officials in Arkansas. In these words in their Assessment and Plan: “The problem of low health literacy is solved when the health literacy of the health care system is in balance with the health literacy of the patients it serves.”

Consistent with that belief system, the responsibility for addressing the health needs of Arkansans through a health-literate public health approach is at the heart of this state health department’s view of its own purpose and

carries into its strategies and day-to-day operations and programs. That is explained in clear terms in the Assessment and Plan in this way: “When you put both sides of health literacy together, there is often a mismatch between the skills of the patients and the demands placed on them by the clinics, hospitals, and insurance companies. This imbalance can result from people having problems with reading, writing, doing math, listening, or asking questions. It can also result from the health system requiring people to do things that are simply too hard to do. In that way, the demands of the health care system are out of balance with the skills of the people it serves.”

The Arkansas Department of Public Health estimates there are 820,000 adults in Arkansas with low health literacy, or roughly 37 percent of Arkansas’ adult population (see Figure 2).

As Figure 2 illustrates, a minimum of 27.7 percent of every county’s population has low health literacy. One public health staff member explained that the state has a greater “portion” than the United States overall of people in groups who are more likely to have low health literacy, such as seniors, people with less than a high school education, and people who live in poverty.

Health literacy as one part of the solution to Arkansas’ high rates of chronic disease, infant mortality, and disability is expressed as not only an imperative, but a given. Thus, in Arkansas, efforts are ongoing to improve health literacy across the lifespan of its residents, and in each of its 75 counties. To multiply the effects of this work in a state that suffers from poor health metrics, it is notable that the Arkansas Department of Public Health has taken up the partnership model for advancing health literacy by joining forces with other statewide units. These include the Department of Education, as well as nongovernmental organizations, such as hospitals and nonprofit literacy councils. These partnerships are designed to multiply health literacy efforts across the state and throughout society more quickly.

For example, there are 30 Reach Out and Read programs in Arkansas that have so far reached about 40,000 children with books and early literacy advice at well-child visits, and more programs are planned in the coming year. In addition, the Arkansas Department of Public Health works with nonprofit literacy councils in more than 60 Arkansas counties to teach adult learners words and concepts related to health while they are learning to read.

Programs to train health professionals in health literacy are described as steadily growing in number, with an uptick having occurred in the past year by adding health literacy into existing continuing education sessions for health professionals. Health literacy is now included in sessions that are taught over closed-circuit television that can be watched from every county in the state.

In another nod toward inclusivity that required agreement about invest-

FIGURE 2 Percentage of Arkansas population with low health literacy.

ing resources, all eight of the University of Arkansas for Medical Science Regional Centers have received training in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit,” with the stated goal of improving how Arkansas’ health care professionals talk with patients and how clinic systems and staff can make it easier for people to get the services they need when they need them.

Perhaps the broadest and most visible multi-sectorial approach to advancing health literacy in Arkansas was formed in 2009, and was catalyzed not only by Arkansas Department of Public Health staff and leaders, but also by volunteers, staff, and leaders of literacy organizations, universities, and health care organizations, as well as individuals who were not sponsored by or professionally affiliated with an organization, but who cared about health and health literacy. Today, the Partnership for Health Literacy in Arkansas is a true statewide coalition and has developed a state action plan with these seven goals, which are not listed in any particular order of importance:

- Share and promote the use of health literacy practices that are based on the best science available.

- Make health and safety information easy to understand so that people who need it can get it and use it to take action.

- Make changes that improve the health literacy of the health care system.

- Include health literacy in the lessons and curricula for all children in Arkansas, from infants in child care through college students.

- Work with the adult education system in Arkansas to improve the health literacy of the people in the communities they serve.

- Do research to better understand and measure what works to improve the health literacy of the public and the health care system.

- Build a network of health literacy partners committed to making changes at their organizations that will improve health literacy in Arkansas.

Finally, it is worth noting that in conversations with Arkansas clinicians, researchers, and administrators, they frequently mentioned that careful efforts were invested by the Partnership for Health Literacy in Arkansas to develop a model for a state action plan based on the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. “The Arkansas Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy” is available at http://phla.net. This action plan is an interactive plan that includes the Partnership for Health Literacy in Arkansas’ seven goals listed above. It provides the opportunity for broad participation by multiple organizations, universities, and agencies, which can submit their own objectives for accomplishing the plan’s goals and strategies. This approach fosters buy-in from stakeholders across the Arkansas health literacy, medical, and population health communities, who can take steps to operate in their own spheres of influence to advance health literacy in the foreseeable future.

Public Health and Health Literacy: What’s Happening?

To further learn about the use, or lack of use, of health literacy within state, local, tribal, and territorial public health organizations, we set out to directly ask individuals working in public health about their attitudes and experiences regarding health literacy.

This effort proceeded simultaneously on two tracks. First, we attempted to directly contact every state’s public health department (and the District of Columbia). This effort used the main e-mail address, telephone contact information, or online contact forms found on the website of each state’s public health department. As needed, we made up to three follow-up attempts to contact each organization.

We asked a single, seemingly simple question, “Who is responsible for health literacy within your organization?”

To date, we have received replies from departments of health in 24 states (see Figure 3). We have received no response from 26 states and the District of Columbia, even though we used the primary point of contact provided to the public from every department of health.

Only 1 of the 24 state departments of public health that responded reported having an individual on staff whose title explicitly indicates health literacy is an area of responsibility. That state is Arkansas. Seven state departments of public health reported they have a designated point of contact or someone whose responsibilities include health literacy. Those states are Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Seven state departments of public health reported that although they did not have a staff person in particular who was a point of contact or who worked primarily in health literacy, they made the point that health literacy is a part of their work. These states are Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Montana, New York, Ohio, and Oregon.

Ten state departments of public health reported that they did not fit the

FIGURE 3 Health literacy within state departments of public health.

previous descriptions and did not report any formal efforts to address health literacy. These states are Alabama, Alaska, California, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

The nature of those responses, of course, made us more curious. So we created an online inquiry using Survey Monkey that targeted professionals who worked within a local, state, tribal, or territorial department of public health. Using Internet-based methods, we widely broadcast an invitation to participate in this effort.

We distributed this request to respond to a brief online inquiry via the following electronic listservs:

- LINCS Health Literacy

- Social Determinants of Health listserv

- Health Education listserv in Los Angeles County

- Public Health Nursing listserv organized by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- Healthcare Information For All listserv

- Healthcare Working Group at the American Public Health Association (APHA) listserv

- Environmental Health listserv from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Public Health Education and Health Promotion listserv of the APHA

We also sent the invitation to participate directly to individuals at the following organizations:

- The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO)

- The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO)

- The National Association of Local Boards of Health (NALBOH)

- The Office for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support at the CDC

- The Arkansas Health Literacy Working Group

In addition, we sent the invitation to participate to more than 400 individuals identified via the APHA member directory online whose titles and affiliations indicate they work at a state, local, tribal, or territorial public health organization. Finally, using social media platforms, we distributed the invitation to participate in the online inquiry through the following:

LinkedIn Groups:

- Health Communications, Social Marketing, and Social Scientists Group

- Health Literacy Exchange

- IHA Health Literacy Conference

- Medical Information Services & Communication

- APHA

- Health Literacy (a subgroup of Plain Language Advocates)

- Health Literacy Nebraska

- Healthcare for Vulnerable Populations to Eliminate Disparities in Health

Google+ Communities:

- Public Health

- Health Communication

- Carpool Health Community

- Wellbound Storytellers

Twitter:

- The week of August 19, 2013, one author (Dr. Rikard) sent out six Twitter tweets related to the online information-gathering effort, with few retweets.

- The week of August 26, 2013, Dr. Rikard sent 20 tweets as well as tweets to 16 specific public health organizations/agencies.

All invitations to participate also encouraged the recipients to broadly share the invitation with their network of public health professionals. The use of social media, electronic listservs, and a snowballing methodology means it is impossible to determine a response rate because we do not know exactly how many individuals ultimately received the invitation. The overall response rate, nonetheless, is clearly exceedingly low, as we received 63 responses. Two responses had to be removed from the sample because individuals who worked at federal-level public health organizations responded to the inquiry, although our invitation specified that the effort was specifically targeted to public health officials at state, local, tribal, or territorial public health organizations.

The 61 valid responses to the online inquiry represent 25 states and 56 state, local, tribal, or territorial public health organizations. On average, they reported being employed at their current public health organization for 10.2 years and within the field of public health for 16.2 years.

Excluding duplicate reports from multiple individuals employed at the same public health organization, participants are employed at organizations that serve an average population size of more than 3 million people (3,122,638) and an aggregate population of 95,437,540, or roughly 30 percent of the U.S. population. The population profile of those communities served by participants are reported to be, on average, 59.7 percent white, 14.4 percent African American, 8.7 percent American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1.8 percent South Asian (India/Pakistan), 6 percent Asian (e.g., China, Japan, Korea, etc.), and 2.2 percent Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander. The population served by participants’ organizations is also reported, on average, to be 17.1 percent Hispanic or Latino in ethnicity. Twenty-five participants reported that their public health organization serves rural areas, 28 reported serving urban areas, and 16 reported serving suburban areas. Thus, the small number of responses does represent a large and diverse array of public health organizations.

Participants were asked how the public health organization where they are employed defines health literacy. In response, seven (12.5 percent) participants reported using the definition from the IOM publication on health literacy commonly used by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The source of that definition was often attributed as the reason the public health organization put forth that definition.

More than half (53.6 percent) of participants reported using one of a variety of other definitions. Two participants (3.6 percent) reported their public health organization is currently in the progress of developing a definition. Five participants (8.9 percent) reported not knowing if their public health organization had a definition of health literacy and 12 participants (21.4 percent) said the public health organization where they work did not have a preferred definition of health literacy.

In more practical terms, 13 participants reported that health literacy was viewed as an issue for only patients and the public; 2 participants reported that health literacy was viewed at their public health organization as an issue for only health care professionals and health systems; and a vast majority of 38 participants said health literacy was viewed as an issue for both sides of that relationship equally.

Participants were also asked to respond to the individual attributes of a health-literate organization developed recently by members of the

IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy (Brach et al., 2012). The question employed a four-point Likert scale with labels of strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), agree (3), and strongly agree (4), and an option to indicate that the proposed attribute of a health-literate organization was not relevant to the mission of the public health organization where participants are currently employed. The scale mean is 2.5, so an average response higher than 2.5 indicates more agreement than disagreement that the public health organization is conducting business in a way that reflects the attribute (see Table 1).

The proposed attributes deemed most irrelevant to the mission of the participants’ public health organization mission (Statements 9 and 10) are the two that focus most on the clinical care context. Overall, each proposed attribute of a health-literate organization received more agreeing responses than disagreeing responses, indicating that participating public health professionals do perceive that their public health organization’s mission aligns with the attributes of a health-literate organization.

Participants were also asked to estimate the percentage of overall effort at their public health organization that is invested in addressing health literacy in some way. Examples given included reviewing publications for plain language or establishing health literacy as an outcome of a program or effort. On average, participants reported that 30.7 percent of the overall effort at the public health organization where they are employed is spent addressing health literacy in some fashion. The lowest response received was 0 percent and the highest was 100 percent, indicating a broad range of perceptions of not only the amount of effort directed at health literacy within public health organizations, but also likely indicating a broad range of understanding of health literacy.

When asked about any trend in the awareness of health literacy during the past 12 months within their public health organization, one participant reported awareness was decreasing, 24 reported awareness had stayed the same, and 23 reported an increasing level of interest in health literacy. The mean response on this three-point scale was 2.5, indicating that health literacy awareness was slightly increasing across the participants’ public health organizations.

We also asked participants to respond to a three-point scale indicating their level of agreement that their public health organization was conducting specific examples of health literacy activities. This scale consisted of the statements, “We have not considered or discussed this health literacy activity,” “We have considered but not implemented this health literacy activity,” and “We have initiated this health literacy activity.” An average response higher than the scale mean of 2 indicates more participants have initiated each health literacy activity than have not (see Table 2).

Both quantitatively, as displayed in Table 2, and qualitatively, par-

TABLE 1 Perceived Relevance of the 10 Attributes of a Health-Literate Organization

| Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Health Literacy: 10 Attributes of a Health-Literate Organization |

||||

| n | Average Response | Number of Participants Indicating Not Relevant to the Organization’s Mission | ||

|

1. Has leadership that makes health literacy integral to its mission, structure, and operations. |

61 | 2.9 | 0 | |

|

2. Integrates health literacy into planning, evaluation measures, patient safety, and quality improvement. |

61 | 3.0 | 0 | |

|

3. Prepares the workforce to be health literate and monitors progress. |

61 | 3.0 | 2 | |

|

4. Includes populations served in the design, implementation, and evaluation of health information and services. |

61 | 2.9 | 0 | |

|

5. Meets the needs of populations with a range of health literacy skills while avoiding stigmatization. |

60 | 2.9 | 0 | |

|

6. Uses health literacy strategies in interpersonal communications and confirms understanding at all points of contact. |

59 | 2.7 | 2 | |

|

7. Provides easy access to health information and services and navigation assistance. |

59 | 3.0 | 0 | |

|

8. Designs and distributes print, audiovisual, and social media content that is easy to act on and understand. |

58 | 3.1 | 1 | |

|

9. Addresses health literacy in high-risk situations, including care transitions and communications about medicines. |

59 | 2.9 | 7 | |

|

10. Communicates clearly what health plans cover and what individuals will have to pay for services. |

59 | 2.8 | 19 | |

ticipants reported that rewriting plain-language materials was the most frequently adopted health literacy activity. Many expressed a view that this was also a very effective strategy for public health organizations to employ. For example, one participant wrote, “Our department web pages have been rewritten to make the information clearer and easier to navigate and understandable by customers. Each division involved a panel of diverse advisors

TABLE 2 Health Literacy Activities Within Public Health Departments

| Which Health Literacy Activities Has Your Public Health Organization Considered or Initiated? |

|||||

| n | Mean of Responses | Number of Participants Selecting (percentage of total) | |||

| Currently Conducting | Considered But Not Conducting | Not Considered | |||

|

1. Rewriting materials to make them easier to read and understand. |

48 | 2.6 | 34 (70.8%) | 8 (16.7%) | 6 (12.5%) |

|

2. Developing an awareness of cultural competencies. |

47 | 2.6 | 33 (70.2%) | 9 (19.1%) | 5 (10.6%) |

|

3. Training staff to communicate with clients in simple, clear language. |

47 | 2.4 | 26 (55.3%) | 16 (34.0%) | 5 (10.6%) |

|

4. Training translators to communicate with clients in simple, clear language. |

46 | 2.2 | 20 (43.5%) | 14 (30.4%) | 12 (26.1%) |

|

5. Rewriting signage so that it is visible and easy to understand. |

46 | 2.2 | 20 (43.5%) | 14 (30.4%) | 12 (26.1%) |

|

6. Piloting new materials with members of intended audience. |

48 | 2.0 | 16 (33.3%) | 18 (37.5%) | 14 (29.2%) |

|

7. Using health topics to teach literacy skills. |

46 | 1.9 | 13 (28.3%) | 15 (32.6%) | 18 (39.1%) |

|

8. Adopting an organization-wide plain-language policy that promotes clear communication between provider and health care consumer. |

45 | 1.8 | 11 (24.4%) | 15 (33.3%) | 19 (42.2%) |

to assist with the rewriting of their websites. A centralized language services program was adopted by the department to increase meaningful access to programs and services for individuals with limited English proficiency.”

Another participant reported that the public health organization where the person works has made addressing plain language an agency wide policy. “The plain-language policy affects all aspects of the health department. Not only those working with health-related materials, but also our Health Communications and Marketing must abide by this policy and ensure all information that goes out to the public is an appropriate literacy level.” That policy was reported to state that “All health communication activities must adhere to Agency policy or practice regarding confidentiality and disclosure of information and will use the principles of effective health literacy.” The participant did not offer further elaboration of what the public health organization defined as principles of effective health literacy.

Other health literacy activities reported as being conducted by more than half of the participants are developing an awareness of cultural competencies and training staff to communicate with clients in simple, clear language.

Most of the health literacy activities we inquired about, however, were reported as being conducted by fewer than half of the participants’ public health organizations. These activities include the following

- Training translators to communicate with clients in simple, clear language

- Rewriting signage so that it is visible and easy to understand

- Piloting new materials with members of intended audience

- Using health topics to teach literacy skills

- Adopting an organizationwide plain-language policy that promotes clear communication between provider and health care consumer

While there is certainly evidence to support the effectiveness of each of those health literacy activities, most participants reported their public health organization was not undertaking those efforts.

Perhaps most revealing was the activity that received the least recognition of having occurred—adopting an organizationwide plain-language policy. Plain language is perhaps the easiest approach to addressing health literacy. While it does not reflect the totality of current understanding of health literacy, the complexity of language is the “front door” to health literacy. For some reason, however, this core activity has not been adopted widely by the public health organizations where this study’s participants are employed.

Inquiring further as to how participants’ public health organizations were responding to health literacy as a potential tool to improve public

health, we asked if the agencies have provided training on health literacy to either health professionals or the public. Twelve participants reported that their public health organization has provided trainings to health professionals while 26 said no and 10 reported not knowing. Nine participants reported that their public health organization has provided training to the public or patients while 26 said no and 12 reported not knowing.

Only one participant reported that the public health organization in question had terminated a health literacy initiative in the past year. The multiple reasons reported for this effort being terminated were a lack of funding, a lack of trained staff, and a lack of interest by constituency.

Seven participants responded that their public health organization has at least one person with primary responsibility to address health literacy. Four participants reported that there is at least one person on staff with health literacy as a part of their formal position title. However, 33 participants reported that their public health organization does not have either a person with health literacy as a primary responsibility or with health literacy in his or her position title.

In parallel, 12 participants reported that their public health organization has one person (3 participants) or multiple people (9 participants) who have primary responsibility to ensure health literacy is addressed by the public health organization’s efforts. Twenty-nine participants reported that within their public health organization, no one has primary responsibility to address health literacy, but many people do address the issue (23 participants), or that no one has primary responsibility, but one person does address health literacy issues (6 participants). Three participants reported that they did not know how health literacy was addressed by their public health organization.

Finally, we qualitatively explored the health literacy activities and perceptions of health literacy at the public health organization where participants are employed.