4

Health Literacy Facilitates Public Health Efforts

APPLYING HEALTH LITERACY PRINCIPLES TO PUBLIC HEALTH EFFORTS IN PREPAREDNESS AND NUTRITION

Linda Neuhauser, Dr.P.H., M.P.H.

University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health

Early in her career as a public health nutritionist, Linda Neuhauser found that her science-based messages were not resonating with her clients. One of her colleagues, having similar disappointing interactions, concluded that “people don’t change, but it’s our job to tell them what to do.” Recognizing a serious problem, she began to explore how to better communicate, and this quest has turned into a lifelong career focused on using participatory processes to design, implement, and evaluate public health educational programs.

As a professor of public health and Principal Investigator of the Health Research for Action Center at the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, Neuhauser said she has the opportunity to work with researchers, students, communication experts, and policy analysts who study issues of health literacy. The group has a special focus on participatory design, which closely engages the intended end users in the development, implementation, and evaluation of communication approaches (Neuhauser et al., 2013a). This work has been ongoing for 20 years and has involved diverse populations across many public health topics throughout the world. Programs designed with such intensive participation work very well, she said, while programs that are not designed in such a fashion usually fail.

BOX 4-1

Seven Steps to Create Public Health “Clear Communication”

- Define audiences and goals

- Set up an advisory group that includes end users and stakeholders

- Identify issues from formative research

- Draft content using health literacy design principles

- Conduct Usability testing—until it works

- Codesign an implementation plan

- Evaluate, revise, and scale up

SOURCES: Neuhauser, 2013; Neuhauser et al., 2013a.

Neuhauser described a seven-step model that focuses on health literacy and has proven to be very successful in developing good communications (see Box 4-1) (Neuhauser et al., 2013a).

The first step is to define the goals of the communication and to clearly identify the intended audiences. A special focus is needed on the diverse groups of end users, especially those who have communication barriers related to literacy, language, culture, and functional and access issues, previously referred to as disabilities, Neuhauser said.

The second step is to set up an advisory group. This group includes the end users and a range of stakeholders. Stakeholders may include researchers, policy makers, providers, community members, funders, the media, government representatives, and people from private industry. Neuhauser noted that an advisory group should represent a microcosm of stakeholders from many sectors that will facilitate the initiative. Its diversity improves the chances of having a successful program.

The third and fourth steps are to identify issues from formative research and then draft content according to health literacy design principles. The fifth step, usability testing, is critical, Neuhauser explained, because even the best known health literacy design principles cannot codify everything needed to make communication understandable, engaging, motivating, and actionable (Neuhauser et al., 2009). To achieve these attributes, strong input is needed from the intended audiences as the communication approach is developed (Neuhauser et al., 2013b). Usability testing involves one-on-one, in-person interviews with members of the focal audiences, especially people with limited health literacy skills and/or other communication barriers. Typically, several rounds of usability testing are required to adequately retest and revise the communication prototype adequately. Guidance from focus groups about prototypes can also be helpful.

The sixth step is to concurrently codesign the implementation. Neuhauser pointed out that even the greatest communication in the world will not be effective if the dissemination plan is not feasible in terms of implementation. This is another area where the input from the advisory committee is critical, she said. Finally, step 7 is to evaluate, revise, and scale up the program. This step also involves the principles of participatory design.

From her review of the literature on health literacy and public health nutrition programs, Neuhauser concluded that there is limited information on this topic in the peer-reviewed research literature and cited the value of the article by Carbone and Zoellner (2012). That article was a systemic review of 33 studies that were primarily related to measurement, development, readability, and assessing patients’ individual health literacy skills. Neuhauser concluded that (1) the current literature does not generally cover broader issues in health literacy; (2) there are relatively few experimental studies on the effectiveness of interventions; and (3) research is needed not only on the individual level, but also pertaining to health systems and communities.

Although some research shows that nutritionists and dietitians are interested in health literacy and that they would like to have training to improve their communication skills, there is little evidence that they are receiving such training, Neuhauser said. If such training is not a requirement of licensing, she added, it will likely not be available in the near future. Therefore, integrating health literacy into licensing requirements is needed in the area of nutrition, as well as for all the other health professions.

Neuhauser described research she conducted to determine whether the government website related to the food pyramid adhered to health literacy principles (Neuhauser et al., 2007a). The website, MyPyramid.gov, was constructed to meet intended readability levels of seventh to eighth grade. However, when the site’s readability was measured, it varied widely from seventh grade to above the college level. Furthermore, there was a lack of cultural relevance, which is very important from a public health perspective. The site also did not include information that pertained to families and communities. Neuhauser’s research found that the website met only half of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Web usability criteria.

When Neuhauser contacted the U.S. Department of Agriculture to find out how the site was developed, she learned that the site content was written by professional nutritionists. The site had been tested with racially and ethnically diverse groups, but they did not specifically select people with low health literacy skills. Rather, the site designers involved a number of college students, which Neuhauser said is a common practice. She reiterated that a core problem in the design of communications is the lack of attention paid to end users, particularly those with health literacy challenges.

Neuhauser described an example of a very successful public health nutrition intervention, the First 5 California kit for new parents. Each year, this multimedia kit is given to 400,000 parents in California. It includes a parenting guide, a guide on what to do when your child gets sick, and a variety of other materials, including videos. Design of the intervention began in 2000 and included testing with diverse audiences and stakeholders. The kit is available in multiple languages with readability kept to the sixth to eighth grade level. According to the evaluation project led by Neuhauser, significant gains in knowledge and improvement in practices in such areas as nutrition and infant feeding were made within 6 weeks of receipt of the kit (Neuhauser et al., 2007b).

The impact of the program was remarkable, Neuhauser said. She added that there are numerous examples in the literature on health inequities where interventions widen knowledge gaps between different groups. Spanish speakers involved in this project had one third less knowledge about parenting practices than did English speakers at the outset of the study. Neuhauser’s team found that 6 weeks after receiving a kit, the Spanish speakers completely erased this knowledge gap when compared to English speakers in the control group. She concluded that when programs are designed according to health literacy principles and intensively involve the end user, good results are achievable. This program has been adapted for use in four other states and overseas, including Australia.

Neuhauser highlighted four other examples of successful public health nutrition campaigns. The first is the California Network for Healthy California (http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/CPNS), which has a website that provides information on the value of increased fruit and vegetable consumption and daily physical activity. A second example is information from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about food safety and nutrition. The third example is a project of the Eli Lilly Company and involves a booklet on healthy eating that was developed using health literacy principles and usability testing, and that was awarded the Institute for Healthcare Advancement’s first place for published materials award in 2008. The final project included a picture of a plate that simply illustrated the size of healthy serving portions. Neuhauser also noted that pharmaceutical companies have invested in improving information they provide to people with nutrition-related diseases, for example, diabetes and hypertension.

On the topic of health literacy and emergency preparedness communication, Neuhauser said she has been working in this area during the past 5 years as part of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–funded project (Neuhauser et al., 2013c). A review of the literature revealed a general lack of evidence on this topic. One study by Friedman and colleagues (2008) analyzed 50 disaster or emergency preparedness websites and concluded that information was not consistently easy to read or visually

appropriate. Neuhauser said such information is needed because vulnerable populations are at extremely high risk for death and injury during disasters. In particular, she identified older adults and people who are deaf and hard-of-hearing (Deaf/HH) as groups for which better research and communication is needed.

Neuhauser reported on projects conducted within Deaf/HH communities. She mentioned that this community is large (estimated at 48 million people) and diverse. She pointed out that many members of the deaf community do not identify as “having a disability,” but instead consider themselves members of a minority linguistic group. They use American Sign Language (ASL) and other forms of communication. ASL is a gestural 3-D language that does not directly translate into a language such as English. Members of the deaf community generally have low literacy. Neuhauser said that any written materials should be at the third to fourth grade reading levels and that this group also needs information in ASL video formats. Neuhauser noted that health literacy standards for video formats are just emerging, and she and her colleagues are working on this area. Their team has conducted a national assessment of the state emergency operations plans in the United States and the U.S. territories to examine whether they included specific operational plans for people with disabilities, people who are Deaf/HH, and older adults (Ivey et al., in press). The research also included an assessment of emergency preparedness materials at community-based organizations for older adults and people who are Deaf/HH in one California county. The research team conducted interviews and focus groups to assess the availability and readability of materials (Neuhauser et al., 2013c). The advisory board for the project included researchers, policy makers, technology experts, community members, and representatives of different Deaf/HH subgroups. According to study findings:

- Only one-third of state plans mentioned the Deaf/HH population.

- Fewer than half of the community organizations serving the Deaf/HH population provided emergency preparedness materials.

- No materials met readability standards for the Deaf/HH community (the lowest was 7th grade and most were above the 10th grade level), and only one resource was at or below the recommended 6th grade level for older adult populations.

Neuhauser’s team found that the vast majority of service providers want plain-language materials. In addition, communication training on how to interact with people who are deaf and hard of hearing is critical for first responders (Engelman et al., 2013; Neuhauser et al., 2013c)

Neuhauser concluded her presentation by summarizing the study recommendations aimed at improving state emergency operations plans,

and policies of the Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and other national, state, and local emergency response organizations (Engelman et al., 2013):

- Provide national guidance to improve U.S. state emergency operations plans.

- Legislate standards for emergency alerts in the United States.

- Develop emergency preparedness materials with members of Deaf/HH populations.

- Adhere to health literacy principles.

- Define health literacy criteria for video formats.

- Use new technology: texts, mobile video, social media.

- Develop training for responders and service providers.

She emphasized that much needs to be done, but that using the seven-step, highly participatory process can greatly improve public health communications.

Jennifer Cabe, M.A.

Canyon Ranch Institute

Cabe said she was introduced to the importance of health literacy by Alice Horowitz and Cynthia Bauer when she served as a speechwriter to the 17th U.S. Surgeon General, Richard Carmona. She reiterated the point made earlier that there is clear evidence that individuals with lower health literacy are more likely to experience

- poorer overall health;

- misunderstanding of their health condition and its treatment;

- lack of adherence to medical regimens;

- low rates of screening and use of other preventive services;

- late stage of presentation for care of a chronic disease;

- increased health care costs;

- hospitalization; and

- death.

Cabe noted it is not yet clear if this relationship is causal or correlative. In preparation for the workshop, she investigated evidence of the converse of this relationship, that is, whether health literacy proficiency is protective in terms of health behaviors and outcomes. In her cursory review of the

literature, she was somewhat surprised to find little in the way of evidence for the potential benefits of such proficiency. For example, high health literacy would logically enable individuals to better retrieve and then process information about their health and then comfortably navigate the increasingly complex health care system. If health literacy proficiency could be directly linked to improved chronic disease outcomes, a strong social and economic argument could be made to promote health literacy. The financial costs of treating chronic diseases, many of which are preventable, are large and mounting, she said. Estimates are that they account for 18 or 19 percent of gross domestic product.1 For every dollar spent on health care, 75 cents is spent on treating chronic disease,2 and recent evidence suggests it is climbing up to 80 cents of every dollar.

Cabe said health literacy proficiency is increasingly important because the orientation toward prevention relies on the self-management of chronic disease, following care plans, making informed decisions and healthy behavior changes, and adhering to complex medication regimens while being alert for side effects and complications. Navigating the health insurance marketplace is challenging for many as well, she said. Millions of people newly eligible for publicly funded or subsidized health insurance in the United States must navigate the system to find, understand, evaluate, communicate, and use information. Gaining access to insurance coverage depends on one’s ability to

- find reliable information;

- understand eligibility guidelines;

- complete forms and provide enrollment documentation;

- understand and apply concepts such as premiums, copayments, and benefits; and

- understand which services are and are not covered.

Cabe added that the ability to make one’s way through the health care system, from primary care to specialist or from acute to long-term care, can itself be challenging and is likely much easier for those with high health literacy.

There is evidence that health literacy is at the core of the nation’s poor international standing in terms of health, Cabe said, citing findings from a recent study by Kindig and Cheng (2013). In their analysis of female mortality by county from 1992 to 2006, they found several factors were

_______________

1 World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS) (accessed July 25, 2014).

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/index.htm [accessed July 25, 2014]).

associated with lower mortality rates, including higher education levels, not residing in the South or West, and low smoking rates. Medical care variables, such as the relative numbers of primary care providers, were not associated with lower rates. The authors concluded that improving health outcomes “will require increased public and private investment in the social and environmental determinants of health, beyond an exclusive focus on access to care or individual health behavior.”

In considering the findings of the Kindig and Cheng (2013) study, Cabe posed the question, “Does it then follow that health literacy can help public health systems to empower people to prevent chronic disease, regardless of socioeconomic status or other social determinants of health?” In her view, factors that are usually missing in public health approaches that impede progress in chronic disease prevention include

- involved and engaged users/audiences;

- linguistically and cultural appropriate messages;

- trust; and

- mutual respect.

Cabe endorsed fellow panelist Neuhauser’s “Seven Steps to Create Public Health Clear Communication” as a way to ensure interventions succeed and are cost effective. The seven steps approach results in involved and engaged users, messages that are understood, and trust and mutual respect. Cabe said these are all essential to sustained behavior change.

Cabe described four important targets for public health interventions: knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. She acknowledged the work of Cecilia Doak and her husband Len Doak, which led to the understanding that improving literacy leads to changing behavior. For example, to transition from learning to read to reading to learn is a significant behavior change. This behavior change is transformative, Cabe added. It allows individuals to understand information, put that information into the context of his or her life, communicate that information to others and, finally, use the information to affect his or her health and well-being.

The assumption that an individual with high health literacy will make healthy choices can be challenged, Cabe said. Some individuals with low health literacy exhibit excellent health behaviors while others with high health literacy have poor health behaviors. She cited the classic example of health care professionals who drink too much, do not manage their stress, or smoke cigarettes.

Cabe discussed the importance of forming partnerships, intervening early and often with individuals, and taking an integrative and team approach to public health interventions. To illustrate these concepts, she shared a testimonial of a Canyon Ranch client, Dean Rutland. Rutland participated in a health literacy wellness program designed by Canyon

Ranch Institute and offered to the Cleveland Clinic patient community. Her testimony, shared with permission, is summarized in Box 4-2.

Cabe said Rutland gives presentations in Cleveland churches to share her experiences. She is helping other people engage in healthy behaviors to

BOX 4-2

Testimony of Dean Rutland

I saw the flyer about the Canyon Ranch Institute Life Enhancement Program (LEP) in my Cleveland neighborhood at a time when I was feeling bad emotionally and spiritually. I knew I needed to do something, so I called to sign up.

I went in for my assessment and got a real shock. I couldn’t do a single sit-up. I couldn’t do jumping jacks or walk for 5 minutes on the treadmill. Then, I got the news that I had high blood pressure. It was so high that they told me to go see my doctor immediately.

I managed to hold my tears inside until I got out of the room, but I began to sob as the elevator doors closed. I was overwhelmed with the reality of what poor health I was in, and I was scared.

At that point, I had no intention of going ahead with the program. But Teresa Brown, the Core Team member who had done my initial assessment, called me at home. She talked to me about putting my embarrassment aside and taking the first step. She also assured me that I would meet others in the group who needed to make changes.

Teresa was right. Before long, I had made some new friends. We would even meet outside the program sessions to walk together. I could tell I was on the right track.

One of the hardest things I had to do was take the blood pressure medicine my doctor prescribed. I had a real “A-ha!” moment when he told me my blood pressure had gone down. With continued progress, I might not even need the medication. I knew I didn’t want to take pills for the rest of my life, so it made me feel awesome to know I had done something so positive.

What I learned in the program helped me to change what I ate and motivated me to move every day. I completely restocked the food cabinet at home. My five children are encouraged to eat better and my daughter in North Carolina even walks with me. We use our phones to connect by voice and picture, and then we talk while we walk “together.”

Since the CRI LEP, I’ve lost 40 pounds, and I finished my first 5K race. When I crossed the finish line, I wanted to keep on going, so now I’m training for a full marathon. I have to give a lot of credit to the CRI LEP, the Core Team members who supported me even after the program ended, my family, and the friends I’ve made.

Yes, I give myself some credit, too, because making changes took some courage. What I want others to know is that once you take that first step, you can’t believe what you can accomplish!

SOURCE: Cabe, 2013.

prevent chronic disease, but is also assisting those living with chronic disease in reducing unhealthy behaviors. Rutland’s story is a positive example of how health literacy can guide public health efforts, Cabe said, adding that health literacy is a powerful tool that can be used in addressing chronic disease. Health literacy can guide public health agencies and the people they serve in choices about where, when, why, and how to invest in chronic disease prevention.

Health literacy is often neglected in public health efforts to prevent chronic disease, Cabe said. When implementing public health interventions, she said the following issues should be addressed:

- engage people early and often;

- do not “dumb down” complex truths;

- explain complex issues carefully and check in often for understanding and action;

- prioritize prevention and wellness, not sick care;

- equally involve health professionals and the public;

- address the social determinants of health; and

- create multisector, effective partnerships.

The social, family, community, and economic costs of chronic disease can be addressed through these approaches, Cabe concluded.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: HARNESSING YOUTH VOICES TO IMPROVE PUBLIC HEALTH LITERACY IN DIABETES

Dean Schillinger, M.D.

San Francisco General Hospital

Schillinger introduced a California-based social marketing campaign titled “The Bigger Picture” that engages young people of color in diabetes prevention. The campaign focuses on painting a picture of the social and environmental conditions that are driving the diabetes epidemic, which is increasingly affecting younger people of color. Gabriel M. Cortez, a poet and campaign spokesperson of Panamanian descent, presented one of his poems that addresses the link between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and diabetes among immigrant communities. A video of his presentation can be found at http://iom.edu/Activities/PublicHealth/HealthLiteracy/2013-NOV-21/Videos/Panel3/Schillinger.aspx).

To describe the purpose of this campaign, Schillinger reviewed the definition of public health literacy as articulated by Freedman and colleagues (2009). Public health literacy is “the degree to which individuals and groups

can obtain, process, understand, evaluate, and act upon information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community.”

According to this definition, the purpose of public health literacy is to improve the health of the public by engaging stakeholders in public health efforts and addressing the determinants of health. Furthermore, public health literacy is viewed as a multidimensional construct, including conceptual foundations, critical skills, and a civic orientation.

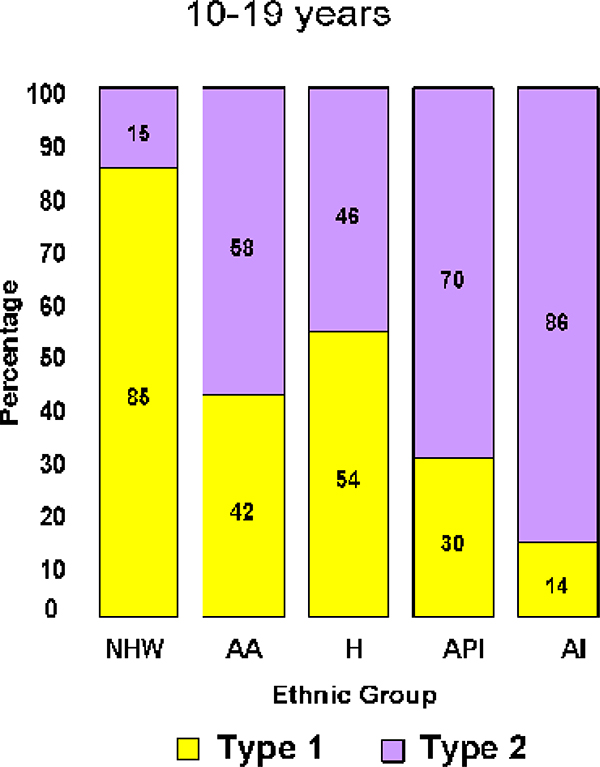

To set the stage, Schillinger reviewed the distribution of diabetes types among U.S. children ages 10 to 19 by race/ethnicity (see Figure 4-1). Among non-Hispanic white children, 85 percent of diabetes cases are represented by Type 1 juvenile-onset diabetes. However, among all other race/ethnic

FIGURE 4-1 Distribution of diabetes types by race/ethnicity.

NOTE: AA = African American; AL = Alaskan Native; API = Asian and Pacific Islander; H = Hispanic; NHW = Non-Hispanic white.

SOURCE: Schillinger, 2013.

groups, about half of diabetes cases, and in some cases the overwhelming majority of diabetes cases, are Type 2, previously known as adult-onset diabetes. Schillinger noted that it is alarming that this so-called late-onset disease is occurring so frequently among children.

Schillinger reviewed the results of a recent national study (May et al., 2012) that found that in 1998, 1 in 11 children ages 12 to 19 had prediabetes or diabetes. In 2009, nearly one in four children in this age group had prediabetes or diabetes. These children have a 50 percent chance of developing frank diabetes3 within 5-10 years. It is important to note that in the intervening 10-year period, body mass index did not change. So although obesity is a strong predictor of Type 2 diabetes, Schillinger said it does not explain this explosion in cases of prediabetes among children.

Schillinger described some activities that have been undertaken as part of “The Bigger Picture” project. Four medically curated writing workshops have been held with participation from 30 poets affiliated with the group, “Youth Speaks” (http://youthspeaks.org). Poets, including Gabriel Cortez, have written 16 English poems that have been featured in public service announcements (PSAs) varying in length from 30 seconds to about 5 minutes. In addition, two Spanish-language PSAs have been produced and five more are in preproduction. Spanish and English websites have been developed (TheBiggerPicture.org) and the organization is active in social media. An educator toolkit has been created that can be used by teachers in high schools. English- and Spanish-language marketing materials and a Bigger Picture DVD have also been produced. The DVD includes many of the PSAs.

Schillinger reported that presentations at high school assemblies are the centerpiece of the project. To date, presentations have been made at 15 minority-serving public high schools. The 1-hour program is moderated by a Youth Speaks poet mentor and includes poet performances and viewing the video PSAs. The assemblies often include approximately 500 high school students who are from low-income neighborhoods.

Topics covered during the assembly program include (1) basic information about Type 2 diabetes; (2) statistics outlining the social and contextual determinants of this disease; and (3) resources and examples for community and policy action. Schillinger added that it is important to review aspects of the etiology of the disease because some students think diabetes is solely genetic because it is so prevalent within their families. Some schools have opted to participate in a supplementary one-hour writing program in which

_______________

3 Frank diabetes is stage 4 of the 5 stages of diabetes and “is characterized as stable decompensation with more severe β-cell dedifferentiation.” http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/53/suppl_3/S16.full (accessed February 20, 2014).

a subset of students write their own poems or stories in response to the assembly presentation.

Like many high school assemblies, the learning environment can be challenging because of rowdy behavior. Schillinger said that holding the attention of an auditorium filled with teenagers is a challenge, especially if the topic is about health. The project, however, has succeeded by featuring the talent of the Youth Speaks poets, who create a hush as soon as their performance begins. As an example, Schillinger asked Jose Vadi to present a poem for the Institute of Medicine (IOM) that is featured in one of the project’s PSAs. The poem is called “Sole Mate” and can be viewed at the Bigger Picture website (http://youthspeaks.org/thebiggerpicture/2013/02/01/sole-mate-3). Diabetes can have harmful effects on feet (amputation), and Jose’s poem explores how dependent we all are on our feet and asks, “What would we do if we lost all or part of one?” It ends with a shocking image of an amputation. The closing statement of the PSA attempts to put this problem in perspective, by reporting that “over 1,000 U.S. soldiers have lost a limb during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. During this same time period, over 70,000 Californians have lost a limb to diabetes.”

Schillinger showed a second PSA that also features a poem by Jose Vadi, “The Corner,” that is about the food environment in his Oakland, CA, neighborhood (http://youthspeaks.org/thebiggerpicture/2013/02/01/the-corner-3). In this poem, Vadi talks about the choices people make and questions whether we are actually making a choice about what to eat, or whether choices are made for us by forces beyond our control.

The campaign has thus far been focused on the San Francisco Bay Area, but expansion to other parts of California is under way. The project team hopes to make the campaign a national one. Through its presentations to date, the project has reached more than 2,500 high school students from 15 low-income public Bay Area schools. In addition, presentations have been made to more than 770 health, education, and community stakeholders. The campaign website has received more than 100,000 hits, and this has occurred with no advertising budget.

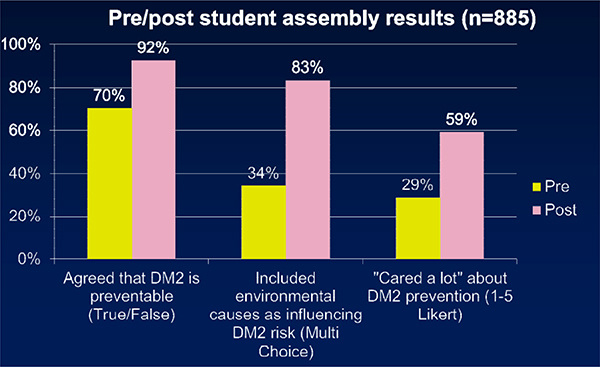

To help gauge the impact of the high school presentations, Schillinger enlisted a random sample of high school students who were given feedback clickers and asked to respond to a series of questions before and after the presentation (see Figure 4-2).

Schillinger reported that before the presentation, 70 percent of the students agreed that Type 2 diabetes is preventable. After the presentation, 92 percent believed it is preventable. Before the presentation, only 34 percent of high school students included environmental and social causes as influencing one’s diabetes risk. After the presentation, 83 percent of the students acknowledged these risk factors. Schillinger said this improvement in knowledge signifies a gain in public health literacy.

FIGURE 4-2 The Bigger Picture assembly improved outcomes.

SOURCE: Schillinger, 2013.

With respect to a call to action and a willingness to engage, Schillinger reported that only 29 percent cared a lot about diabetes prevention before the presentation. This rose to 59 percent of students answering five on a five-point Likert scale indicating “I care a lot about preventing diabetes.”

Evaluations among stakeholders found that before seeing the videos and hearing the poems, 67 percent believed that young people can serve as agents of social change. After seeing the videos, this response rose to 99 percent. Ninety-six percent of stakeholders reported that the strategies used in this project, that is, youth-generated, spoken-word pieces, were relevant to their organization.

Schillinger concluded by reviewing The Bigger Picture project’s next steps. Plans are to expand the Bay Area school visit program to other schools throughout the state, but initially to cities hard hit by the recent recession (e.g., Richmond, Stockton, and The Inland Empire in California). Eventually the program could be expanded nationally because Youth Speaks has sister programs throughout the United States. Schillinger added that he would like the project to extend to other chronic diseases because the social and environmental conditions causing diabetes are also causing hypertension, heart disease, and other conditions. In addition, there are plans to enhance and evaluate the Bigger Picture’s digital platform and to increase the campaign’s impact by developing and incorporating materials and content in other languages.

Alice M. Horowitz, Ph.D., R.D.H.

University of Maryland School of Public Health

Alice Horowitz pointed out that oral health is not generally viewed as an integral part of overall health. Yet oral diseases are often called a neglected epidemic. Among children ages 2 to 4, early childhood caries has increased 33 percent between 1988 and 2004 (Dye et al., 2007). It is now recognized as the most common disease of childhood.

Oral health literacy has been defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic oral health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (National Center for Health Statistics, 2010). Horowitz said many people do not use appropriate preventive procedures, not by informed choice, but because they have never been taught about them, have no skills to seek information, or have no access to them. Increased oral health literacy provides people with the understanding and the means to exercise choice rather than suffering the consequences, she said.

Low levels of oral health literacy are associated with poor knowledge about oral health (Jones et al., 2007; Sabbahi et al., 2009), infrequent dental visits (White et al., 2008), greater severity of dental caries or tooth decay, higher rates of failed appointments (Holtzman et al., 2012), and lower oral health-related quality of life (Gong et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Richman et al., 2007). Horowitz said these correlations between health literacy and oral health outcomes have only been documented in recent years and parallel findings regarding health literacy and medicine.

Horowitz reviewed the well-established interventions known to prevent or control tooth decay, especially when applied early for children. These interventions include fluoridation of public water supplies; appropriate use of fluoride toothpaste; application of pit and fissure sealants; reduction in sweets; and periodic visits to the dentist. Most people, if asked about how to prevent tooth decay, would likely reply, “brush your teeth twice a day.” According to Horowitz, relatively few would mention the use of fluoride and dental sealants. She noted that dental visits generally do not prevent oral health diseases because, as is the case in medicine, such visits are generally for diagnosis and treatment. She added that much of oral disease prevention is done at home, and what is needed are behavioral interventions.

The Maryland Dental Action Coalition, formed following the death of

Deamonte Driver,4 developed a state plan with three focus areas: access to oral health care; oral disease and injury prevention; and oral health literacy and education.

To address aspects of the oral health literacy and education focus area, the School of Public Health conducted a statewide needs assessment using focus groups and a telephone survey of a random sample of Maryland adults who had children ages 6 years and younger, Horowitz said. The survey asked respondents what they knew about preventing tooth decay, and how they rated the communication skills of their dental providers. The results of the survey indicated that low-income adults with young children do not understand how to prevent tooth decay (Horowitz et al., 2013a). They do not know what fluoride is, that fluoride is in their water, and that drinking tap water helps to prevent tooth decay. Horowitz said 98 percent of the central water supplies in Maryland are optimally fluoridated. However, adults in the survey who have Medicaid dental coverage did not know this. Most were drinking bottled water despite the cost and the impact on the environment. People with low incomes tend not to drink tap water for a variety of reasons: some complain of the taste or the color of the water, but a major factor is “keeping up appearances.” However, most bottled water does not include a sufficient amount of fluoride to prevent tooth decay, she said.

In addition to assessing adults with young children, surveys and focus groups of physicians, nurse practitioners, dentists, and dental hygienists also were conducted in Maryland (Horowitz et al. 2013a,b; Maybury et al., 2013). Providers were asked what they know and do about preventing tooth decay and whether recommended communication skills are used on a routine basis. According to survey results, providers do not use recommended communication techniques. Most respondents had never even heard of the teach-back method and certainly were not using it. This finding held across all provider groups. In addition, health care providers, including the dentists and dental hygienists, need to have training reinforced on how to prevent tooth decay, Horowitz said. For example, according to the survey, little or no attention was given to teaching mothers to clean their infant’s mouth and to check for early childhood tooth decay or white spots, early signs of decay. Similar disappointing findings emerged from the focus groups and surveys conducted of Head Start and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program coordinators and staff.

Another barrier to oral health is that many dental care providers do not accept Medicaid-eligible children or pregnant women, said Horowitz. A

_______________

4 Deamonte Driver was a 12-year-old boy from Prince George’s County, Maryland, who died from a brain infection that was the result of an abscessed tooth. His mother had been unable to get him adequate dental care.

pregnant woman age 21 and older is automatically dropped from Medicaid immediately after giving birth. Yet, Horowitz said, bacteria that cause tooth decay are generally transferred from the mother to the infant. The Maryland Dental Action Coalition is attempting to change this Medicaid coverage policy.

From a health literacy perspective, the findings from the information gathered represented “a perfect storm,” Horowitz said. The IOM report Advancing Oral Health in America recommended community-wide public education on the causes of oral diseases and the effectiveness of preventive interventions (IOM, 2011). The report also recommended professional education and best practices in preventing oral diseases and in improving communication skills.

A health literacy environmental scan also was conducted that included 26 out of the 32 public health dental clinics in Maryland that are located in Federally Qualified Health Centers, and city and county health departments. The methodology for the scan was consistent with that recommended by Rima Rudd and included in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s toolkit. The results of the scan indicated that thousands of dollars are being spent annually to treat early childhood caries. In some cases, very young children have to be treated for severe early childhood caries in operating rooms under general anesthesia.

Given the public’s lack of knowledge of prevention, the educational materials available through the dental clinics were assessed. Only one leaflet was found in some of the clinics that discussed water fluoridation, but it did not adhere to plain-language principles and included too much information. It is going to be rewritten, Horowitz said.

Based on the statewide oral health literacy assessment, a “Healthy Teeth, Healthy Kids” initiative was established by the Coalition in collaboration with the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Office of Oral Health (http://healthyteethhealthykids.org). The purpose of this initiative, according to Horowitz, is “to help moms help themselves and their infants to have good oral health.” The initiative provides education to pregnant women through prenatal classes, WIC and Head Start programs, and high school programs for pregnant teens. Horowitz said that it is especially important to work in city and county health departments because programs are colocated and are under one umbrella. This means that the WIC program runs alongside the obstetrics and pediatric clinics. In these environments, it is difficult for staff to add dental issues to their already busy schedules because there is a tendency to address the client’s problem of the moment, she said.

Horowitz reiterated the importance of mothers needing to understand the importance of drinking fluoridated tap water and using fluoride toothpaste. She said that mothers need to clean their infants’ mouths as soon as

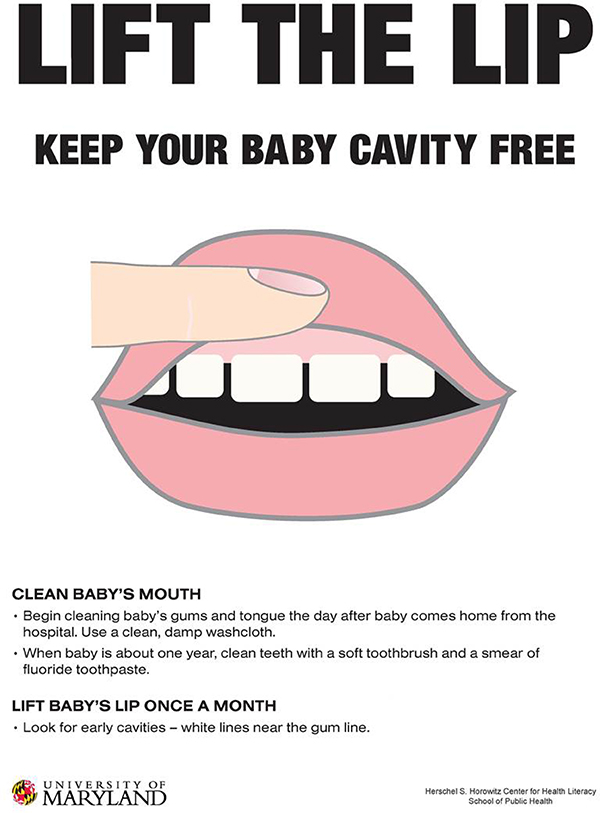

they begin to bathe their babies. She has observed that in prenatal classes, mothers are taught how to clean every orifice of the body except the mouth. The cleansing of the mouth needs to start early because by the age of 6 months, when the first baby tooth comes in, infants are likely to resist a new practice. If cleaning the baby’s mouth starts early, it becomes an established habit over time. The initiative also teaches mothers to lift the baby’s lip once a month to look for white spots or lines on the teeth. This is an early sign of decay and at this point the teeth can be remineralized or healed. Other components of the educational intervention focus on the need to limit sweets and to have a 1-year dental examination. Horowitz said that 45 states now encourage and reimburse physicians to use fluoride varnish on infants up to several times a year. Fluoride varnish is very effective, but most people, especially those with low incomes, do not know about it, Horowitz said.

Several educational tools have been developed that are targeted to pregnant women and women with young children: a video, posters, leaflets, and magnets, all in both English and Spanish. The poster shown in Figure 4-3 provides guidance on cleaning a baby’s mouth and checking for early signs of decay. The posters have been mounted in dental and WIC clinics and other clinical areas.

Although the ultimate indicator of the net effectiveness of a preventive regimen is its ability to actually prevent the targeted disease or condition, it is also necessary to measure knowledge and actual use of the recommended preventive regimen, Horowitz said. For example, if adults do not understand the value of community water fluoridation, they are not likely to get their drinking water from the tap. Horowitz described a major new focus area that is part of the state plan called “Get It from the Tap.” The main message is that fluoride prevents cavities. This initiative and “Lift the Lip” have posters, magnets, and videos that are used to disseminate the messages.

In terms of next steps, Horowitz said the Maryland Dental Action Coalition will implement all of the education tools developed thus far in the settings serving pregnant women and women with young children. The educational tools were tested on that target audience, and the participating women told the design team what they wanted to see. The video features mothers because women said they wanted to hear from other moms, not doctors or dentists. Once the program is implemented, Horowitz said, the team will reevaluate knowledge and understanding of caries prevention among women, providers, and the public. In addition, the team will determine the percentage of infants who are free of caries. The goal is to reduce the number of children who are taken to the operating room for general anesthesia and treatment.

FIGURE 4-3 Poster providing guidance on preventive dental care.

SOURCE: Herschel S. Horowitz Center for Health Literacy

Bockrath asked panel member Neuhauser about the language used for preparedness communications. In particular, she asked, “What kinds of tools are available pertaining to preparedness language? Is it possible to avoid creating a whole new language around the next major public health issue?” Bockrath said that until 9/11, there were about 10 preparedness-specific words. Since then an entire new public health vocabulary has emerged that requires translation for communication purposes. Neuhauser, in her work with deaf individuals, found that many words related to disasters were not available in American Sign Language. She found that developing glossaries of important words was very helpful.

Neuhauser said that medical students learn about 18,000 new words during their training. A whole new language of jargon is acquired and later used on the unsuspecting public. Health literacy has involved “dejargonizing” this vocabulary for the intended users. She added that in a high-risk situation such as a disaster, the associated emotional stress can diminish cognitive skills, making understanding communications difficult.

McGarry asked Cabe whether, when discussing prevention activities, confusion arises when distinctions are made in the context of public health among primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. Cabe agreed that these aspects of public health do confuse people. In her experience some have a hard time understanding how a chronic disease can be prevented before there are any signs of it. Then, after a chronic disease such as diabetes is diagnosed, some of the communications shift to secondary and tertiary prevention, for example, avoiding an amputation. Schillinger said there is also confusion between prevention in terms of individual behavior change and the broader view of community change. He added that many of these distinctions depend on an understanding of human biology, disease, and health. These are areas where education is needed, especially in the era of the development of biomarkers and other risk factors.

Vadi, speaking from his experience of working with The Bigger Picture project, said it was important to distinguish the communications that put behavioral messages in a binary form: “if you do this, this will happen to you, and if you do that, bad things will happen.” The PSA that featured the egg on the frying pan to illustrate the effects of drugs on the brain was not nearly as effective as talking about a framework that describes individuals in the context of their community and the influences of the community on the individual. As an example, he pointed out that individuals have the ability to choose whether or not to buy a pack of junk food. However, some individuals live in “food deserts,” areas where their access to healthier options is extremely limited. Vadi concluded that individuals have to take responsibility for their health, but that individual responsibility is greatly

affected by the environments in which they live. He said that policies shape those environments; for example, the corn subsidies that were put in place in the 1970s have contributed to the Type 2 diabetes epidemic through the public’s consumption of high-fructose corn syrup sugar-sweetened beverages. Many complex factors influence behavior on the individual, community, and policy levels. In Vadi’s view, some public health messages used in the past have been oversimplified and too focused on individual choices without taking into account the complex influences of community- and policy-level factors.

Pleasant thanked the presenters from The Bigger Picture campaign and said they illustrated the vast range of approaches to addressing public health from a health literacy perspective. He pointed out that art, including the poetry from The Bigger Picture, is an important but sometimes neglected form of public health communication. Pleasant noted that artists can express opinions and create change by engaging people and defining what the ideal future should look like. He suggested that Vadi and Cortez read the work of Augusto Boal, who is from Brazil and writes about art and social change.

Vadi responded that although art can be extremely dogmatic, he has learned through the workshops that in order to be effective, the artist cannot become too hyperbolic. To communicate effectively and engage as many people as possible, he said it is important to let the audience know that the poem comes from a place of concern and not necessarily just rage. To identify solutions Vadi has found it useful to look at the current world, identify why things are flawed, and then turn to the past and analyze the change between past and present to discover the future. Vadi referred to a poem called the “Quantum Field” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIL3kdE7mKk). This poem was written by a young man named Tele’Jon Quinn, a graduate of Met-West High School in Oakland, who lives in a food desert. The poem is about a young man who tries to live a healthy lifestyle by working out and eating healthy food. However, he lives in a Twilight Zone world called the Quantum Field where his efforts are not appreciated. This poem is a reminder of the importance of cultural influences. He added that if you are a high school student going off campus at lunch to buy a kale salad while everyone else is seeking junk food, you are going to be ostracized.

Sarah Fine, the Bigger Picture project director, added that the workshops try to take a social justice perspective and shift the conversation from a “blame-the-victim scenario” to one that focuses on the environmental and systemic forces that affect chronic disease. She added that the messages need to go beyond “don’t drink this soda or eat this food” and address issues such as why there are fewer resources allocated for outdoor spaces in poor neighborhoods than in wealthy neighborhoods. Again, it is important to

examine the driving forces behind why individual choices are made. Fine gave an example of a woman who participated in the sugar-sweetened beverage workshop. This woman came into the workshop with a liter of Coke, but when she learned about sugar industry tactics that target minorities, she left the workshop with the commitment not to drink any more soda. This woman’s motivation to change came about because she realized that she was being exploited, Fine said. This type of message is much more motivating than one that tries to dictate “good” behavior.

Isham asked the panel to discuss ways to “scale up” effective public health communication programs. Horowitz said it is important to ensure that a pilot program makes a difference clinically before it is disseminated on a larger scale. The evaluation process can take a long time. The oral health intervention targeted to pregnant women will be implemented and evaluated in one Maryland county. Horowitz estimated it will take some time to demonstrate effectiveness because oral health will be tracked for several years. Once the program has been shown to improve oral health, it could go statewide and be adopted by other states. Isham asked about the process of transferring the knowledge gained in one state to another state. Horowitz said that if states realize they can benefit financially by preventing young children from being treated for severe tooth decay, they will eagerly adopt the program.

Schillinger stated that with respect to The Bigger Picture project, all that is needed is a major underwriter because platforms to launch the program and reach a wider audience are available through the national organization, Youth Speaks, which has a presence in most major urban areas. Social media and the program’s Web presence are also useful mechanisms for dissemination. When approaching potential donors, Schillinger said it is important to have a sustainability plan. In response to questions about the feasibility of corporate sponsorship, Cabe discussed the value of developing partnerships with academic institutions, other nonprofits, and companies. Such partnerships allow program piloting, evaluation, replication, reevaluation, and then dissemination. Cabe said that in her experience at the Canyon Ranch Institute, public health agencies can work with corporations with the appropriate guidelines in place, for example, receiving unrestricted educational grant funding and adhering to strict evaluation protocols.

Neuhauser noted that there is a science and art to scaling up. She recommended exploring the World Health Organization Expandnet (WHO, 2008). Criteria include having a champion and participatory design. Neuhauser said sponsors are available who want to make a difference and Cabe added that corporations are interested in expressing their social responsibility.

Neuhauser expressed an interest in creative partnerships and asked representatives of The Bigger Picture project where they would go when seek-

ing a sponsor. She wondered about technology companies. Vadi responded by highlighting the power of social media. He mentioned that one of their videos, “The Product of His Environment,” was showcased on UpWorthy. com and garnered more than 15,000 views in 1 day. This website acts as a gatekeeper for videos and graphics with social messages. This site, and others like it, immediately generates views and can engage an entirely new audience that a California state-specific program would otherwise be unable to reach. These sites also open up opportunities for collaboration. Through Twitter and Facebook, the project has reached many diabetics and former diabetics who have created their own local “mom and pop” organic distribution companies throughout California, Vida said. The project has also engaged other young people and other storytelling organizations. Vida pointed out that The Bigger Picture is, in and of itself, a collaboration between the University of California, San Francisco, Center for Vulnerable Populations and Youth Speaks, a literary organization. He discussed the exciting cross-fertilization that occurred between the poets and Schillinger. Vida added that collaboration inherently strengthens projects, and the digital landscape can be used in many ways to expand audiences.

Cabe, J. 2013. Chronic disease prevention. PowerPoint presentation at the Institute of Medicine workshop on Implications of Health Literacy for Public Health, Washington, DC, November 21.

Carbone, E. T., and J. M. Zoellner. 2012. Nutrition and health literacy: A systematic review to inform nutrition research and practice. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 112(2):254-265. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.042. Epub January 25, 2012.

Dye, B., S. Tan, V. Smith, B. Lewis, L. Baker, G. Thornton-Evans, and C. Li. 2007. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 11:1-92, data from the National Health Survey.

Engelman, A., S. L. Ivey, W. Tseng, D. Dahrouge, J. Brune, and L. Neuhauser. 2013. Responding to the deaf in disasters: Establishing the need for systematic training for state-level emergency management agencies and community organizations. BMC Health Services Research 13:84. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-84.

Freedman, D. A., K. D. Bess, H. A. Tucker, D. L. Boyd, A. M. Tuchman, and K. A. Wallston. 2009. Public health literacy defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(5): 446-451.

Friedman, D. B., M. Tanwar, and J. V. Richter. 2008. Evaluation of online disaster and emergency preparedness resources. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 23(5):438-446.

Gong, D. A., J. Y. Lee, R. G. Rozier, B. T. Pahel, J. A. Richman, and W. F. Vann, Jr. 2007. Development and testing of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Dentistry (TOFHLiD). Journal of Public Health Dentistry 67:105-112.

Holtzman, J. S., M. W. Gironda, and K. A. Atchison. 2012. The relationship between patients’ oral health literacy and failed appointments. Paper presented at National Oral Health Conference, April 28-29, Milwaukee, WI.

Horowitz, A. M., J. C. Clovis, D. V. Kleinman, and M. Q. Wang. 2013a. Use of recommended communication techniques by Maryland dental hygienists. Journal of Dental Hygiene 4:181-192.

Horowitz, A. M., D. V. Kleinman, and M. Q. Wang. 2013b. What Maryland adults with young children know and do about preventing dental caries. American Journal of Public Health 103:e69-e76.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Advancing oral health in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ivey, S. L., W. Tseng, D. Dahrouge, A. Engleman, L. Neuhauser, D. Huang, and S. Gurung. In press. Assessment of state- and territorial-level preparedness capacity for serving deaf and hard of hearing populations in disasters. Public Health Reports.

Jones, M., J. Y. Lee, and R. G. Rozier. 2007. Oral health literacy among adult patients seeking dental care. Journal of the American Dental Association 138:1199-1208.

Kindig, D. A., and E. R. Cheng. 2013. Even as mortality fell in most U.S. counties, female mortality nonetheless rose in 42.8 percent of counties from 1992 to 2006. Health Affairs (Millwood) 32(3):451-458.

Lee, J. Y., R. G. Rozier, S. Y. Lee, D. Bender, and R. E. Ruiz. 2007. Development of a word recognition instrument to test health literacy in dentistry: The REALD 30—a brief communication. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 67:94-98.

May, A. L., E. V. Kuklina, and P. W. Yoon. 2012. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among U.S. adolescents, 1999-2008. Pediatrics 129(6):1035-1041.

Maybury, C., A. M. Horowitz, M. Q. Wang, and D. V. Kleinman. 2013. Communication techniques used by Maryland dentists. Journal of the American Dental Association 144:1386-1396.

National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. Healthy People 2010 final review. Hyattsville, MD.

Neuhauser, L. 2013. Applying health literacy principles to public health efforts in preparedness and nutrition. PowerPoint presentation at the Institute of Medicine workshop on Implications of Health Literacy for Public Health, Irvine, CA, November 21.

Neuhauser, L., R. Rothschild, and F. M. Rodríguez. 2007a. MyPyramid.gov: Assessment of literacy, cultural and linguistic factors in the USDA food pyramid web site. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39(4):219-225.

Neuhauser, L., W. L. Constantine, N. A. Constantine, K. Sokal-Gutierrez, S. K. Obarski, L. Clayton, M. Desai, G. Sumner, and S. L. Syme. 2007b. Promoting prenatal and early childhood health: Evaluation of a statewide materials-based intervention for parents. American Journal of Public Health 97(10):813-819.

Neuhauser, L., B. Rothschild, C. Graham, S. Ivey, and S. Konishi. 2009. Participatory design of mass health communication in three languages for seniors and people with disabilities on Medicaid. American Journal of Public Health 99:2188-2195.

Neuhauser, L., G. L. Kreps, and S. L. Syme. 2013a. Community participatory design of health communication programs: Methods and case examples from Australia, China, Switzerland and the United States. In Global health communication strategies in the 21st century: Design, implementation and evaluation, edited by D. K. Kim, A. Singhal, and G. L. Kreps. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Neuhauser, L., G. L. Kreps, K. Morrison, M. Athanasoulis, N. Kirienko, and D. Van Brunt. 2013b. Using design science and artificial intelligence to improve health communication: ChronologyMD case example. Patient Education and Counseling 92(2):211-217.

Neuhauser, L., S. L. Ivey, D. Huang, A. Engelman, W. Tseng, D. Dahrouge, S. Gurung, and M. Kealey. 2013c. Availability and readability of emergency preparedness materials for Deaf and Hard of Hearing and older adult populations: Issues and assessments. PLOS ONE. http://www.plosone.org/search/simple;jsessionid=1DE900D57963AF0032D4AAE59396FE91?from=globalSimpleSearch&filterJournals=PLoSONE&query=neuhauser+ivey&x=0&y=0 (accessed April 28, 2012).

Richman, J. A., J. Y. Lee, R. G. Rozier, D. A. Gong, B. T. Pahel, and W. F. Vann, Jr. 2007. Evaluation of a word recognition instrument to test health literacy in dentistry: The REALD-99. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 67:99-104.

Sabbahi, D. A., H. P. Lawrence, H. Limeback, and I. Rootman. 2009. Development and evaluation of an oral health literacy instrument for adults. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 37(5):451-462.

Schillinger, D. 2013. The Bigger Picture: Harnessing youth voices to improve public health literacy in diabetes. PowerPoint presentation at the Institute of Medicine workshop on Implications of Health Literacy for Public Health, Irvine, CA, November 21.

White, S., J. Chen, and R. Atchison. 2008. Relationship of preventive health practices and health literacy: A national study. American Journal of Health Behavior 32(3):227-242.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2008. Scaling up health services: Challenges and choices. Technical Brief No. 3. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/delivery/technical_brief_scale-up_june12.pdf?ua=1 (accessed February 21, 2014).