5

Supporting Public Health Implementation and Research

DEPARTMENTS OF PUBLIC HEALTH: WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

Don Bishop, Ph.D.

Minnesota Department of Health

In 2012 the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) identified health literacy as an opportunity to address health equity, Don Bishop explained. The Department benefitted from the initiative of Genelle Lamont, who was able to focus on health literacy for 1 year as she completed a DHPE (Directors of Health Promotion and Education) Health Promotion Policy Fellowship program. Subsequently, Lamont was hired by the MDH Oral Health program with funding in part to continue her work in health literacy.

The definition of health literacy found in the report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (IOM, 2004), focuses on individuals and their empowerment, which, while appropriate in the clinical context, does not work as well for public health, especially at the state level, Bishop said. Health departments are often addressing systems issues and communicating with decision makers and power brokers rather than individuals. The World Health Organization (2009) recommended that the definition of health literacy be expanded in scope to include social determinants of health. But the definition proposed by Freedman is more applicable to public health, Bishop said, because it has a focus on groups and the community (Freedman et al., 2009). As stated in an earlier presentation by Schillinger, Freedman defines public health literacy as “the degree to which individuals

and groups can obtain, process, understand, evaluate, and act on information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community.”

Bishop said he would make one change to Freedman’s definition. Instead of saying “the community,” he would say “their community” because, in his opinion, public health literacy is also about empowering individuals and groups within a community to develop the necessary skills and influence for working with key decision makers so that policy choices will be made toward the betterment of their community.

Bishop highlighted barriers to health literacy that have been documented in the literature (Zarcadoolas et al., 2003) include the following:

- Complexity of written health information in print and on websites.

- Lack of health information in languages other than English and inadequate translations.

- Lack of cultural appropriateness of health information.

- Inaccuracy or incompleteness of information in mass media.

- Low-level reading abilities, especially among undereducated, elderly, and some segments of ethnic minority populations.

- Lack of empowering content that targets behavior change as well as direct information (social marketing strategies).

Bishop said the Minnesota Department of Health is addressing the lack of cultural appropriateness of health information (item number three) because of the large and growing immigrant population in the state. In recent years there has been an influx of individuals from East and West Africa. He added that there is an established Hmong population from Laos and Vietnam and a rapidly growing Hispanic population.

To illustrate some of the challenges of working with the state’s immigrant population, Bishop described a Diabetes Prevention Program that had been successfully used with the uninsured and Medicaid populations. When implemented within the Somali population, the program had to be adapted several times before it engaged the audience. The sessions had to be shortened, rearranged, and made to be more hands-on with the use of graphic materials. The results, in terms of weight loss and physical exercise, were disappointing; however, there was some improvement in body mass index at the conclusion of the modified program. Bishop suggested that a research study is warranted to see if the incorporation of some health literacy principles into a redesign of the program would improve its effectiveness.

Bishop described some of the sociodemographic characteristics of Minnesota that are barriers to health literacy:

- By 2030, the number of Minnesotans over age 65 will double so that the elderly will represent 20 percent of the population. He

-

said that poorly educated rural Minnesotans are a potential target group for health literacy interventions.

- The state’s schools have become increasingly segregated with, in Bishop’s opinion, charter schools diverting resources from the public schools. A student’s worldview is narrower in a segregated school environment.

- In 2012, half of students of color graduated from high school in 4 years. For the white population, the rate was 84 percent.

- Homeownership is nearly twice as high in the white, non-Hispanic population (76 percent) than it is in populations of color (39 percent).

- Roughly 25 percent of the foreign-born adult population (of any race) lack a high school degree (or equivalent) as compared to 6 percent who were born in Minnesota. Of all the African American children in the state, 35 percent have a foreign-born parent. Among children under age 20, one in six is the child of an immigrant; for children under age 5, it is one in five.

- In 2011, among those under age 65, 29 percent of Hispanics and 25 percent of African Americans who were foreign born lacked health insurance.

- Minnesota includes 12 Native American reservations. Many Native Americans lack health insurance (23 percent), but most have access to the Indian Health Service.

Bishop said the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, including an expansion in Medicaid coverage for those living below 138 percent of the federal poverty level, is expected to reduce the number of Minnesota residents who are uninsured by half (from 485,000 in 2010 to between 159,000 and 254,000 in 2016).

Using data from the 2007-2011 American Community Survey, areas projected to have low health literacy were mapped by Census tract (see Figure 5-1). A low health literacy composite score (from 0 to 6) was calculated that considered six sociodemographic attributes of Census tracts. Areas that were projected to have the lowest health literacy were considered to be those tracts with two to six of the following attributes:

- Fewer than 25 percent of residents were non-Hispanic white.

- More than 15 percent of residents reported that they spoke English “less than very well.”

- More than 20 percent were foreign born.

- More than 16 percent were living in poverty.

- More than 23 percent were 65 or older.

- Fewer than 75 percent had completed more than a high school education.

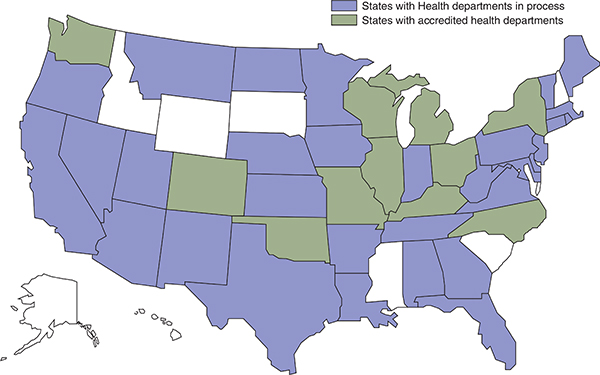

FIGURE 5-1 Status of accreditation of public health departments.

NOTE: Distribution of Health Departments map is updated weekly on the PHAB website under News, Latest News and Events, http://www.phaboard.org/distribution-of-health-departments-in-e-phab. Reprinted with permission.

SOURCE: PHAB, 2011.

The cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul were found to have a much higher prevalence of low health literacy relative to the rest of the state. Seventy Census tracts (65 within the Twin Cities Metro Area) had at least three or more risk factors, with poverty, limited English, and being foreign born seen in combination in 80 percent of those tracts. Age (over 65 years) was a factor in only one of those tracts. Throughout the more rural parts of Minnesota, 17 tracts met two or more of the risk criteria, with poverty being present in 90 percent and age in 50 percent of those tracts.

Bishop described an intervention used within an East African community to help residents understand and use the U.S. health care system. Trained community health workers made home visits and explained how primary care and urgent care visits could be used instead of the emergency room. This pilot program included more than 500 visits to community members that reduced emergency room visits by half and cut per-patient cost by more than 40 percent. One aspect of the program that was particularly effective was a nurse telephone line that included bilingual staff, Bishop said.

In March 2013, the Center for Health Promotion held a 1-day health literacy workshop. The goal of the workshop was to create a public health workforce at the Minnesota Department of Health that was fluent in health literacy principles and best practices. The learning objectives included the following

- Define health literacy and describe conceptual models.

- Discuss the individual, medical, public health, economic, and political importance of health literacy.

- Identify populations vulnerable to low health literacy rates.

- Describe effective use of theory-based models in the design and evaluation of culturally sensitive health-literate materials.

- Give examples of basic concepts for communicating with a diverse audience (e.g., cultural competency, participatory action and learning).

- Apply lessons learned from the workshop to current public health work for improvement and use in future work.

All workshop participants completed the online health literacy training course available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy). For many participants, this was their first exposure to health literacy. The workshop participants also reviewed the guide at the CDC website, Simply Put: A Guide for Creating Easy-to-Understand Materials. The participants were asked to assemble a work team from their program area (e.g., heart disease, stroke, diabetes,

BOX 5-1

Center for Health Promotion Health Literacy Workshop Agenda

Morning

- Health literacy overview: Don Bishop, Ph.D., Minnesota Department of Health

- Using health behavior theory to target, design, and evaluate health messages: Marco Yzer, Ph.D., University of Minnesota

- Implementing health literacy in a state public health department: Jennifer Dillaha, M.D., Arkansas Department of Health

Lunch

- Video Screening: Say It Visually!: Stan Shanedling, Ph.D., Minnesota Department of Health (http://www.health.state.mn.us/cvh) (several 20-sec-ond public health messages were shown)

Afternoon

- Break-out group activity building on preworkshop homework applying health literacy tools/strategies to existing Minnesota Department of Health activities: led by Alisha Elwood, M.A., LMFT, Minnesota Health Literacy Partnership, Blue Cross Blue Shield Minnesota

- Panel discussion: Communicating with a diverse audience (Panel: Genelle Lamont, Moderator, M.P.H., DHPE Fellow; Maria Veronica Svetaz, M.D., M.P.H., Hennepin County Medical Center; Sara Chute, M.P.P., Minnesota Department of Health; Mary Beth Dahl, R.N., Stratis Health)

- Wrap-up and final thoughts

SOURCE: Bishop, 2013.

oral health), select a communication item from their area, test it for health literacy, and then try to improve it.

The workshop had 85 participants. The agenda for the workshop is shown in Box 5-1. Bishop said the workshop was well received, but that participants would have liked additional time for practice and feedback with the training exercises. There are plans to develop a standard course that would be available in the health department for new staff and continuing education. In addition, to further advance health literacy at the Minnesota Department of Health, there are plans to

- create a health literacy committee;

- work toward creation of a full-time health literacy coordinator;

- develop a health literacy guidance document;

- develop and formalize staff training curricula in health literacy;

- develop staff competencies and performance measures and monitor written and oral communications for health literacy (a checklist);

- conduct regional health literacy workshops for local public health agencies and communities; and

- develop a State Health Literacy Action Plan with Minnesota partners.

Bishop highlighted the need to consider health literacy as a part of health equity and mentioned that health literacy could be integrated into an upcoming Health Equity Report to the state legislature.

ACADEMIA: PROFESSIONAL TRAINING AND CERTIFICATION

Olivia Carter-Pokras, Ph.D.

University of Maryland School of Public Health

Carter-Pokras said she has worked in public health education and training for three decades, the past 10 years of which have been spent in academia, including 6.5 years in an accredited school of public health. She currently serves on the Education Board for the American Public Health Association (APHA).

The Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) is the accrediting body for public health schools and programs. The Council has accredited 51 schools and 102 programs, and is reviewing 30 applications for accreditation. According to the Council’s most recent data, more than 10,000 public health students graduated in 2009. Enrollment in nonaccredited public health programs exceeded that of accredited programs. Among graduates of accredited programs, 6,700 earned a master’s of public health (M.P.H.) degree. Twenty schools and 8 programs have undergraduate programs in public health. Carter-Pokras added that public health is one of the fastest growing majors in the country. In fall 2013, CEPH finalized procedures for accreditation for new undergraduate programs.

The Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health has developed a core competency model that includes a section on health literacy. Under its competency related to diversity and culture, the Association states that a graduate of an M.P.H. program should be able to explain why cultural competence alone cannot address health disparity. Graduates should also be able to differentiate among the terms “linguistic competence,” “cultural competency,” and “health literacy” in the context of public health practice. The Association’s study guide for students planning to take the

examination for certification in public health does not include the definition of health literacy. The study guide does, however, include the definitions of linguistic competence, cultural competence, and cultural and linguistic competence. In Carter-Pokras’ view, this represents a shortcoming and something that could be corrected.

Carter-Pokras, as a graduate of the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, investigated how health literacy was addressed at the school. Carter-Pokras found that within the M.P.H. competencies, there is a section called social and behavioral competencies. There is no specific mention of health literacy, but communication issues are addressed. According to the competencies, graduates with an M.P.H. from Johns Hopkins should be able to “formulate communication strategies for improving the health of communities and individuals and preventing disease and injury.”

According to Carter-Pokras’ discussions with teaching staff at Johns Hopkins, health literacy is discussed briefly in two of the required courses—Tools of Public Health Practice and Decision Making, and Problem Solving in Public Health. Neither of the courses has assigned readings on health literacy. Instead, the topic is embedded in discussions related to communication. An elective health literacy course is offered.

Carter-Pokras said that the absence of a focus on health literacy at Johns Hopkins is likely not unique and that similar findings would probably be observed in schools across the country. She talked to a site visitor for the CEPH accreditation process and learned that during site visits, specific content areas under diversity and culture are not examined in detail.

Turning to undergraduate public health education, Carter-Pokras described CEPH’s new guidelines for accreditation as having a section on skills, domains, cross-curricular concepts, and diversity. She noted that all of these topics pertain to health literacy. For example, under skills, the ability to communicate public health information to diverse audiences is included. The guidelines do not explicitly say health literacy, but it fits well under these sections. CEPH has provided some examples of competencies for undergraduate public health programs. For example, Temple University includes the competency, “differentiate among linguistic competence, cultural competency, and health literacy in public health practice.” Temple offers several courses that could include health literacy, including “Ethnicity, Culture, and Health” and “Health Communication.”

Carter-Pokras next addressed the issue of whether schools with public health programs are meeting the needs of the workforce. She discussed the status of accreditation of public health departments as of November 2013 (see Figure 5-1). The map in Figure 5-1 shows those states that are accredited (green) and those that are in the process of becoming accredited (blue). Carter-Pokras noted that the accreditation process provides an

BOX 5-2

Accreditation Standards for Public Health Agencies

- Standard 3.1: Provide health education and health promotion policies, programs, processes, and interventions to support prevention and wellness.

- —Health literacy should be taken into account, and information should be provided in plain language with everyday examples.

- Standard 3.2: Provide information on public health issues and public health functions through multiple methods to a variety of audiences.

- —Produce materials that are culturally appropriate in other languages, at low reading level, and/or address a specific population that may have difficulty with the receipt or understanding of public health communications.

- Standard 7.2: Identify and implement strategies to improve access to health care services.

- —Lead or collaborate in culturally competent initiatives to increase access to health care services for those who may experience barriers due to cultural, language, or literacy differences.

- Standard 11.1: Develop and maintain an operational infrastructure to support the performance of public health functions.

SOURCE: PHAB, 2011.

opportunity to promote health literacy because several standards pertain to health literacy (see Box 5-2). Carter-Pokras indicated that Standard 11.1 is where training fits because, in her view, it is an essential component of operational infrastructure.

Carter-Pokras said the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice includes 18 organizations interested in how public health training is meeting workforce needs. The Council has identified the following core competencies for public health professionals:

- Communication skills

- Tier 1 (entry level): Identifies health literacy of populations served (e.g., ability to understand and use available health information)

- Tier 2 (program manager/supervisor): Assesses health literacy of populations served

-

- Tier 3 (senior manager/executive): Ensures that the health literacy of populations served is considered throughout all communication strategies

- Cultural competency

- All tiers: Incorporates strategies for interacting with persons from diverse backgrounds (e.g., cultural, socioeconomic, educational)

Carter-Pokras described some materials from Día de la Mujer Latina, an organization that, as part of its mission, trains Promotores or community-based health educators (http://diadelamujerlatina.org/promotores/training). When outlining their core competencies, this group lists health literacy and the CLAS standards (Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services) as components of the “communication skills” competency. Carter-Pokras has found that health literacy is often covered in training programs under the areas of cultural competency, health equity, or health disparities. She recommends working with individuals in these areas to incorporate health literacy into their training instead of trying to promote a new mandate for health literacy training. Health literacy and cultural competency can both be appropriately addressed under the rubric of communication skills and interpersonal skills.

As another example of continuing education, Carter-Pokras described a health literacy initiative at the New York City Health Department. The health department received outside funding for 3 years to improve its ability to communicate effectively with functionally illiterate adults. Workshops were held to cover topics such as cultural competency, easy writing, language issues (interpretation and translation), and communication. The training at both the basic and advanced levels reached 800 staff members. Satisfaction with the program was assessed, but there was no evaluation of the program’s long-term impact, for example, to see if it changed trainee behavior and practice. At the conclusion of the 3-year funding cycle, the health literacy training stopped.

Carter-Pokras said there is a need for the topics of health literacy and cultural competency to be integrated within training programs and that such integrated curricula need to be evaluated. With support from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, experts in cultural competency, health literacy, and health disparities were convened to discuss their common aims, both programmatically and from a research perspective. Carter-Pokras noted that there are common themes within the two areas of health literacy and cultural competency, and the overarching goal of training in these areas is to reduce disparities. The two topics also rely on a common communication skill set aimed at improving the quality of care. Carter-Pokras observed that curricular time is limited and there is

resistance to adding more to what is already being demanded. She added that training has to make efficient use of limited time. In collaboration with the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and with input from these meetings of experts, a primer was developed that identified core competencies and enumerated relevant resources (http://dhmh.maryland.gov/mhhd/CCHLP/SitePages/Home.aspx). One of the resources identified in the primer is the online training for health professionals available through the Health Resources and Services Administration that integrates cultural competency and health literacy.

Research questions were also identified through these meetings that pertain to both health literacy and cultural competency (Lie et al., 2012), including the following:

- What are “best practices” in health literacy and cultural competency training?

- What are effective teaching methods?

- What faculty development is necessary?

- How can we include community stakeholders for health professional training?

Carter-Pokras observed that many players are involved in public health education and health literacy. She added that the requirements for students enrolled in public health programs are not yet synchronized with workforce needs. She has found that health literacy education is variable in public health schools and programs and that education in cultural competency or communication may cover aspects of health literacy. However, in her view, there is much work to be done before the topics are well integrated. For example, she reviewed the indexes of textbooks focused on health disparities and cultural competency that were on display at the November 2013 annual meeting of the APHA and found that none mentioned health literacy. It is imperative that those working on cultural competency and health literacy collaborate and work toward their common goals, Carter-Pokras concluded.

Ruth Parker, roundtable member, asked the panel whether a good workforce needs assessment has been completed to inform public health education curricula. Bishop replied that although there is an awareness of the need for such an assessment at the Minnesota Health Department, one has not been performed. He added that in Minnesota, the state agency is separate from the local public health departments. When the local departments heard about the health literacy workshop that was held for staff at

the state health department, they indicated that they also needed training and asked for it. Bishop said the state health department considered conducting regional workshops, but was not sure that the expertise was available locally to offer such workshops. Bishop added that financing such training has become more difficult. The Center for Health Promotion used to have a budget of about $10 million, but it is down to $6 million and is expected to decline even further. Bishop said that trying to bring in outside expertise for health literacy training is, therefore, very difficult.

Carter-Pokras pointed out that as part of the public health accreditation process, schools and programs are supposed to conduct a needs assessment that involves contacting potential employers to identify needed areas of training. They are also supposed to check with alumni to find out if, upon graduation, they were well equipped with the skills needed for their job. She gave an example of feedback from a graduate from the University of Maryland’s Department of Behavioral and Community Health. When asked about areas of training that could be augmented, this graduate said that in her experience, students are not well prepared to work in low-resource areas. For example, students may, during their training, learn to use qualitative software such as In Vivo, but find that their work environments cannot afford to pay for such software. In other environments, the computers are old and not able to run the software. In general, Carter-Pokras said that students learn about best practices, but are not prepared for the financial and other limitations they encounter in public health settings. This graduate also suggested that the technical jargon and language used to describe research findings and methods need to be simplified, perhaps using diagrams and plain language, so that they can be understood. The graduate observed that it is not just people with low literacy who need such simplified messages. Relatives and members of the community who may have graduated from high school often have difficulty understanding the work of public health practitioners. Carter-Pokras reiterated her point about the accreditation process—reviewers look to see whether the necessary components of a program are in place and not how such components are developed.

Dillaha asked Bishop whether there had been any pushback following the health literacy workshop and whether the workshop had had an impact on the health department’s centers. Bishop replied that not as much has happened following the workshop as he had hoped, in part because of limited staffing. However, staff who are very interested in health literacy have been hired. The white paper that will be written for the legislature in 2014 will provide an opportunity to raise awareness of health literacy and how it relates to social determinants of health. He added that the Office of State Health Improvement was recently awarded $20 million a year to support community health programs. Bishop said that building a health literacy focus into these programs could greatly improve program outcomes.

McGarry asked the panel whether the Certification for Health Educa-

tion Specialist (CHES) pays enough attention to health literacy. Carter-Pokras did not comment on CHES, but said that in her view the certification for public health exam does not sufficiently cover health literacy. She added that the certification requirement for public health programs barely covers issues related to diversity and culture, and students are not getting sufficient exposure to these areas.

McGarry asked the panel whether, in the context of the patient-centered medical home, health coaches and health educators who are trained in public health are the optimal providers to promote health literacy in clinical environments and public health programs. Carter-Pokras replied by emphasizing the need to look at process and systems in promoting health literacy. She said the entire system needs to be responsive to health literacy and there should not be a focus on just one discipline as being primarily responsible. In her view, everyone in schools of public health and all public health workers should be exposed to health literacy and understand how it fits into their work. Bishop added that the scope of health literacy needs to be broadened and fully incorporated into the mission of health departments. Bishop said that the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials would be a good partner in terms of furthering health literacy in public health departments and programs.

Rob Logan from the National Library of Medicine commented that the lack of health literacy-related curricular materials in schools of public health likely explains some of the deficits seen within public health programs. He asked the panel to comment on the courses on health literacy that are offered to undergraduates not associated with a public health program or track. Carter-Pokras replied that some of these courses help undergraduates improve their own health literacy and their ability to search and understand health information for themselves and for their loved ones. Students in public health should acquire these skills, and in addition, be able to improve the health literacy of the populations they will eventually serve. Logan added that he is interested in finding examples of model health literacy efforts directed to elementary, high school, and undergraduate students.

Neuhauser raised the issue of missed opportunities and highlighted the need to consider health literacy in the context of the accountable care organizations created through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In her view, not enough attention has been paid to health literacy in these organizations and, she suggested, health competencies should be developed for them. Carter-Pokras said that in her experience, individuals and organizations do not want to be confronted with yet another set of competencies. She has found that a single set of core competencies that addresses both cultural competency and health literacy is responsive to this sentiment. Bishop agreed that incorporating health literacy into programs focused on diversity issues, such as the Many Faces conference in Minnesota, is desirable.

Introduction

Michael Villaire, M.S.L.M.

Institute for Healthcare Advancement

Villaire introduced Cecilia Doak, who he described as a pioneer and one of the founders of health literacy. She and her husband, Leonard Doak, wrote what is considered the ultimate document in health literacy, Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. This seminal work was published in 1985 and reprinted in 1996. It is no longer in print, but it can be downloaded from the Harvard School of Public Health website.1

Villaire described the “fortuitous pairing” of the Doaks. Cecilia had focused professionally on public health and patient education, while Leonard came from an adult education and literacy tutoring background. Villaire said one of the attributes of this couple was their spirit of inquiry. They posed questions, made observations, and then got to work. Through their nonprofit organization Patient Learning Associates they presented more than 200 workshops on health literacy for groups of doctors and allied health personnel. Over the years, they analyzed and rewrote more than 2,000 health instructions. A key component to their evaluations was asking the people who had received the materials if they worked. These evaluations led Leonard, in particular, to appreciate the role of pictures in educational materials.

Villaire discussed the creation of the Leonard Doak Memorial Health Literacy Scholarship in 2012 to honor the recently deceased Doak. The first scholarship was presented at the Institute for Healthcare Advancement Health Literacy conference held in May 2013. This scholarship will provide training for students who will subsequently promote health literacy in underserved areas.

Presentation

Cecilia C. Doak, M.P.H.

Doak described some of her early work in health literacy. In June 1978, she and her husband Leonard delivered the first public health address on the problem of health literacy at the Western Branch Public Health Association meeting. The paper, “Health Education for Illiterate Adults,” signaled the

_______________

1 The book, Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills, can be downloaded at http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/healthliteracy/resources/teaching-patients-with-low-literacy-skills (accessed July 25, 2014).

beginning of the Doaks’ long career in health literacy. Doak said her husband’s interest in health literacy stemmed from his volunteer work. Upon retiring as an electrical engineer, he became a volunteer tutor and taught adults how to read and write. Doak described her early career as a Commissioned Officer in the U.S. Public Health Service working on continuing education for physicians. When she retired, she asked her husband, “What do your students do when they go to the doctor?” He replied that his students “fake it” to avoid embarrassment. The low literacy adults feared that doctors would not treat them if the doctors knew the patients did not understand what the doctors were saying. This realization was the impetus for the Doaks’ subsequent work on health literacy.

Doak described an early study completed in 1979 on patient comprehension. This assessment was conducted at the Public Health Service Hospital in Norfolk, Virginia. The study focused on the measurement of comprehension and listening skills. She said the research and the practices of the reading community and the studies in adult education provided the knowledge and skills necessary to complete this work.

Doak spoke about working with Dr. Tom Stitch and his interest in the literacy classes that were being held in group settings. The move to group classes was in response to the great demand for literacy training experienced in the inner parts of Washington, DC, and other cities. In addition to working with low literacy individuals, Doak described working with professionals. The Doaks were sought out by many organizations in need of health literacy training for their staff members. These organizations included the National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Johns Hopkins University, and many public health federal and state agencies, hospitals, clinics, and medical centers. There was great demand for their training. Doak noted that the term “health literacy” was probably coined in the early 1980s.

From a historical point of view, tremendous progress in health literacy efforts has been made, Doak said. She noted the existence of excellent training and research programs as described throughout the Institute of Medicine (IOM) workshop. She discussed the importance of collaboration between the health literacy and adult education communities. The need for such partnerships was called for over 10 years ago with the report Communicating Health: Priorities and Strategies for Progress (HHS, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2003). The IOM report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (2004) also underscored the importance of these partnerships. Doak said there are good examples of collaboration between health literacy and adult education. In particular, she cited the Health Literacy Study Circles developed by Dr. Rima Rudd (http://www.ncsall.net/fileadmin/resources/teach/nav_ch1.pdf). In Doak’s view, this project provides an outstanding example of how to design and implement the health literacy components of the tasks that adults are expected to

perform. This program focuses on the goals of the literacy demand placed on individuals and the actions necessary for the individual to meet literacy challenges. Doak said this focus is one of the most important missing links in a typical patient education program.

Collaboration in other arenas is also important, Doak said. She cited her research collaboration with Dr. Peter Houts. They found that the use of pictures in educational materials enhanced subjects’ attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence (Houts et al., 2005). Technology is another area where collaboration and research are needed, said Doak. She cited a paper in the November 2013 issue of Scientific American titled “Why the Brain Prefers Paper” (Jabr, 2013). According to this paper, while e-readers and tablets are becoming very popular, reading on paper still has its advantages.

Doak concluded that the future for health literacy is strong and wide open, and will always depend on thoughtful attention. She closed with her favorite quotation: “It’s not what they read, it’s what they remember that makes them learned.”

Bishop, D. 2013. Departments of public health: Workforce development. PowerPoint presentation at the Institute of Medicine workshop on Implications of Health Literacy for Public Health, Washington, DC, November 21.

Freedman, D.A., K. D. Bess, H. A. Tucker, D. L. Boyd, A. M. Tuchman, and K. A. Wallston. 2009. Public health literacy defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(5): 446-451.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2003. Communicating health: Priorities and strategies for progress. Washington, DC: HHS.

Houts, P. S., C. C. Doak, L. G. Doak, and M. J. Loscalzo. 2005. The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Education and Counseling 61(2):173-190.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2004. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jabr, F. 2013. The reading brain in the digital age: Why paper still beats screens. Scientific American 309(5):48-53.

Lie, D., O. Carter-Pokras, B. Braun, and C. Coleman. 2012. What do health literacy and cultural competence have in common? Calling for a collaborative health professional pedagogy. Journal of Health Communication 17(Suppl 3):13-22.

PHAB (Public Health Accreditation Board). 2011. Standards and measures version 1.0. http://www.phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/PHAB-Standards-and-Measures-Version-1.0.pdf (accessed March 18, 2014).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2009. 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion. Track 2. Health literacy and health behavior. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/7gchp/track2/en (accessed February 21, 2014).

Zarcadoolas, C., A. Pleasant, and D. S. Greer. 2003. Elaborating a definition of health literacy: A commentary. Journal of Health Communication 8(Suppl 1):119-120.