8

Peer-Led and Peer-Focused Programs

Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- Bullying is not necessarily an emotional reaction but rather an attack on another youth, and it can be induced by coercion or contagion of aggressive actions by peers. (Dishion)

- Interventions that support adult involvement, positive relationships, group management skills, and nonaggressive norms in schools can have positive effects on problem behaviors. (Dishion)

- Individual interventions are more likely to be effective and cost beneficial than group interventions that bring together aggressive youth. (Dodge)

Much of what happens among adolescents happens away from adults, said Jonathan Todres of the Georgia State University College of Law, who moderated the session on peer-led and peer-focused programs. “They are experts, in many respects, on their lives and the lives of their peers,” he said. Two speakers explored the potential of bullying prevention programs to tap into that expertise.

PEER IMPACT ON CHILD DEVELOPMENT

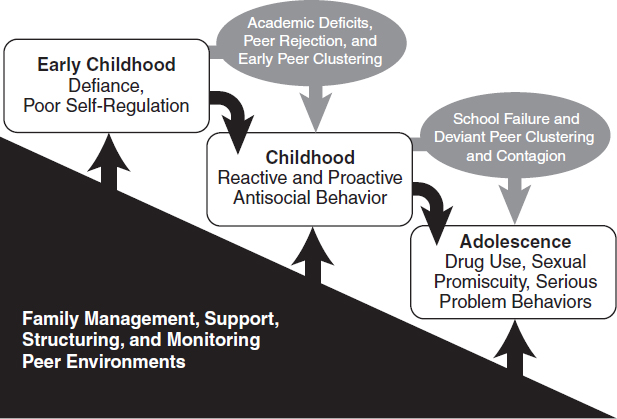

Youth who exhibit behavior problems as adolescents often have traveled along a developmental trajectory in which parenting contributions and amplifying mechanisms have led to a cascading series of problems, including reactive and proactive antisocial behavior (see Figure 8-1), explained Thomas Dishion, the director of the Prevention Research Center and a professor of psychology at Arizona State University. Bullying tends to be a proactive behavior, he observed. It is not necessarily an emotional reaction, but rather a planned attack on another youth.

Two microsocial dynamic processes can amplify these problem behaviors: coercion and contagion, Dishion explained. Coercion is negative reinforcement—or escape conditioning—for peer aggression. “If I escalate and the person backs down, I am more likely to escalate and be aggressive in the future,” he said. Contagion is mutual positive reinforcement for antisocial talk and behavior among peers, which also has been called deviancy training. For example, Dishion explained, in deviancy training a child might talk about something deviant, a peer laughs, the child escalates the story, and the peer further encourages the behavior. After just 30 minutes of videotaped

FIGURE 8-1 Parenting contributions and amplifying mechanisms can lead to a developmental cascade of problem behaviors.

SOURCE: Dishion presentation, 2014.

observation of such conversations, children are much more likely to perform deviant acts, Dishion said. These are normal rather than pathological behaviors, he emphasized, and developmentally they can happen as early as kindergarten. “Kids will aggregate on the playground, and they will start to reward each other for these types of aggressive positions,” he said. “That clustering will lead to more and more aggressive acts.”

Gang Formation

Recently, Dishion has also been looking at what he called coercive joining, where aggressive youth achieve status by forming a gang. Since at least the beginning of the 19th century, Dishion noted, gangs have existed in the United States, and they remain prevalent in many impoverished neighborhoods and cities. Several factors predict gang involvement (Dishion et al., 2005). For females, these factors include a history of antisocial behavior, a history of rejection by peers and teachers, and poor grades. For males, the same factors are involved as well as peer acceptance. “Some of the kids who we think are potentially problematic are higher social status in the peer group,” Dishion said. “That might be part of the dynamic that maintains bullying and aggressive behavior.”

Gang involvement is important in the progression from youths being aggressive on the playground to being dangerous in the community, Dishion said. When 16-year-olds are videotaped interacting in the laboratory, they can be seen talking about victimizing other people, whether members of the other gender or some other outgroup, he said. They escalate their aggressive behavior and can exhibit a struggle for dominance in the room. That dynamic predicts young adult dangerousness, Dishion said, including assaults, robberies, and violence. Yet the fact that it is occurring at age 16 suggests that at least some of these dynamics are malleable, he said.

In some neighborhoods, aggressors achieve more status by becoming more dangerous. For example, Djikstra et al. (2010) have shown that in some neighborhoods in New York, carrying a weapon gives youth greater status. “This is part of the issue that we need to understand,” Dishion said.

Moderating the Influence of Peers

A number of factors moderate peer influence, Dishion said. Youth with higher levels of self-regulation and lower impulsivity are less influenced, for instance, while youth with a history of peer rejection tend to be more influenced by peer norms. Some young people embrace a false consensus by perceiving that peers endorse the deviant norms. And adults who skillfully monitor or structure peer environments can reduce contagion, Dishion added. “I like to think of it as adult leadership,” he said. “Having adults

be in a leadership role, taking a stand, and dealing with these minor events when they are occurring and not letting them escalate is certainly a key to moderating peer influence.”

Dishion also pointed to several conclusions and promising directions that emerge from this work. Interventions that support adult involvement, positive relationships, and group management skills are likely to have positive effects on problem behavior and also to reduce peer coercion and contagion, he said. Examples include the Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports program, the Good Behavior Game, and the Olweus program. Mobilizing parents in a way that puts them in a leadership role is also part of the solution, he said.

Instilling nonaggressive norms in the context of schools is likely to have positive effects, Dishion said. Norms are important, as is leadership about the kinds of norms that are guiding interactions in a school or neighborhood, he added.

Finally, more attention needs to be paid to preventing the self-organization of youth into groups that promote aggression and victimization, Dishion said, and these interventions need to start in childhood. “The development of identity around a gang is very difficult to reduce or treat once it has happened,” he said. “But prevention is certainly possible, and there is some evidence to suggest that even family-based interventions can reduce the involvement of gangs in early adolescence.”

PEER INTERVENTION PROGRAMS

Kenneth Dodge, the William McDougall Professor of Public Policy and director of the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University, discussed two approaches to the prevention of bullying. The first is to build social competencies within the aggressor. This can be done one-on-one with an adult trainer and the individual child, it can be done in groups in which the bullying child is interacting with non-aggressive peers, or it can be done in groups of other aggressors, Dodge said.

The techniques to help a child build social skills that will help that child refrain from bullying and aggression have improved dramatically in recent decades (Dodge and Sherrill, 2006). Interventions that have proven effective include cognitive behavioral therapies, cognitive behavioral skills building, social skills building, and social problem-solving training, Dodge said.

However, most policies are not directed toward individual skill building, Dodge said. Instead, the most common way to deal with an aggressive or deviant child is to place that child with other deviant peers in systematic interventions. For example, group therapies or milieu therapies are common in mental health and account for more than one-half of the expenditures in the mental health arena for aggressive behavior, Dodge said. In the area of

education, he noted, a variety of interventions—tracking, special education, in-school suspensions, and alternative schools—place children with similar issues together. And the juvenile justice system places delinquents in training schools and boot camps and incarcerates them, with group-based interventions accounting for more than 90 percent of juvenile justice expenditures, Dodge said. “It is our most common public policy for dealing with aggression and bullying,” he said.

Among the rationales for peer group interventions are that they are less costly, they afford role playing and practice, they enable manipulation of peer group reinforcement, and they help youth feel comfortable, Dodge said. However, Lipsey (2006) found that, on average, group interventions are one-third less effective than individual interventions. Furthermore, many group interventions yield net adverse effects. About 42 percent of the prevention programs that Lipsey studied yielded net adverse effects, as did 22 percent of the probation programs in that study. As a result, Lipsey concluded that individual interventions are more effective and cost beneficial, Dodge said.

This conclusion, which was based on a comparison of different interventions, was supported by an experimental test using an intervention called Coping Power, which is a social-cognitive skill building intervention for 8- to 14-year-old aggressive children. The experiment compared the effectiveness of the intervention administered to individuals versus the intervention administered to groups, Dodge explained. In the study of 360 aggressive fourth-grade children in 20 different schools who were randomly assigned at the school level to receive Coping Power either individually or in deviant-only groups, the findings were somewhat mixed immediately after treatment (Lochman et al., 2013). There was some tendency for homogenization, with the most aggressive children becoming less aggressive and the least aggressive children becoming more aggressive. However, at the 1-year follow-up, the children who received the individualized intervention had much greater reductions in externalizing and internalizing problems than did the children who received the group intervention.

For situations where it is not possible to administer the intervention individually, Dodge said, strategies exist to mitigate the iatrogenic effects—that is, the negative effects on individuals caused by the treatment itself—from being part of deviant peer groups. Strong training for experienced adult group leaders, the use of behavioral reinforcement strategies, teaching strategies that emphasize clear instructions, and emphasizing a peer-culture norm of non-deviance can all reduce the negative influences of peers, Dodge said. Other approaches are to limit unstructured time with peers, to monitor hot spots where peers congregate, to limit the interaction opportunities of the peer group members by mixing children from different schools or communities, and using short-duration interventions, he said.

Changing the Peer Culture

The second approach Dodge discussed was working with the peer environment and culture to reduce the reinforcement of bullying. Two promising approaches are the Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS) program (Waasdorp et al., 2012) and the Supporting Early Adolescent Learning and Social Success (SEALS) model (Farmer et al., 2013).

SEALS is a teacher-training and directed-consultation model that helps teachers with managing social dynamics, enhancing academic engagement, and improving classroom behavior management, Dodge explained. In a trial in 28 middle schools randomly assigned to receive either the SEALS teacher training intervention or a control, teachers trained in the SEALS intervention were more accurate at understanding peer affiliations and became better managers of the classroom (Farmer et al., 2013). Their students made greater academic achievement gains and reported valuing school more and feeling a greater sense of belonging in the school. Students also perceived a more supportive school and peer context and interacted more with more normative peers rather than just academic peers. The researchers have not yet reported whether the intervention reduced bullying or aggression, Dodge said.

Research Conclusions

Dodge provided four conclusions that he drew from his review of the research. First, programs, placements, and treatments that bring deviant peers together should be avoided whenever possible, he said. Such strategies include training schools, boot camps, Scared Straight, Guided Group Interaction, the Gang Resistance Education and Training Program, midnight basketball, hangouts, non-structured after-school programs, and long prison terms mandated by three strikes laws. Highly structured after-school programs may be effective, he said, depending on who is in those groups.

His second conclusion was that effective alternatives to deviant peer-group placement should be encouraged. Examples of such alternatives include individual therapies such as functional family therapy, multisystemic therapy, and multidimensional treatment foster care; therapeutic courts; early prevention programs such as the High/Scope Perry Preschool, and Fast Track; programs that combine high-risk and low-risk youths such as 4-H, school-based extracurricular activities, boys and girls clubs, scouting, and church activities; and universal peer-culture interventions like PBIS and SEALS. For older youth, Job Corps, individual skills training, and efforts to disperse rather than increase gang cohesiveness are good approaches, Dodge said.

When placement with peers is inevitable, specific measures should be implemented to minimize its impact, Dodge said. Highly susceptible youths, such as slightly delinquent early adolescents, should not be placed with deviant youths, and deviant youths with older, more deviant peers or peers with similar problems from the same community should not be combined. Experienced leaders are needed and should have training, Dodge said, and youths need to be placed in highly structured environments with little free time. It is possible to reduce problems by monitoring youths’ behavior closely and keeping their placements short, he said.

Finally, practitioners, programs, and policy makers should document placements and evaluate the impacts of those placements, Dodge said. The record needs to include a description of the placement environment and of peers, he added.

Structuring School Systems and Classrooms

One interesting application of engineering a positive peer culture, which came up in the discussion session, involved the structure of middle schools. Sixth graders who go to an elementary school have less drug use, fewer school suspensions, less deviant behavior, and higher academic test scores than sixth graders who spend their time with seventh and eighth graders, Dodge said. And, most important, those effects hold not only while the children are in sixth grade but into high school. “There is something about the way we engineer schools that we might rethink,” he said.

During the discussion period, Dodge also addressed the issue of the extent to which adverse peer influences can be offset by positive peer influences. “Imagine you are the superintendent of a school system,” he said. “Twenty percent of your children are deviant. Where do you place them? Are you going to have a net overall positive effect by sending them off to an alternative school or tracking them, even though it might have a negative effect on them? Is it going to have a positive effect on the other 80 percent who do not have to deal with them? After all, these placements are directed by parents of the non-deviant kids who do not want deviant kids with their well-behaving child.” Dodge has been involved in research that has indicated the existence of a critical mass effect. If a class includes no more than three elementary or early middle-school children who were suspended in the previous year, he said, then those children typically have a minimal impact on their classmates. But once the number exceeds a critical mass, the deviant peer influence seems to outweigh the positive peer influence. “There may be ways to engineer the whole system to maximize the positive influence and minimize the deviant peer influence,” Dodge said.

YOUTH LEADERS

Another topic that arose during the discussion period was the influence of youth leaders on their peers. Group interactions, Dishion said, can have many effects, some positive and some negative. Youth who have turned their lives around can be especially effective leaders, but they also can have relapses and continued problems. “There is a danger there as well,” he said. “You cannot emphasize enough structuring these environments so that you really have a handle on them.”

Dodge pointed to empirical evidence that aggressive children are, by and large, disliked by the larger peer group in kindergarten, first grade, and second grade, but by middle school the aggressive child is more popular, at least in some contexts. In this case, he said, “one might think about how to get those deviant peer-group leaders who have influence to use their influence in a positive way rather than a negative way.”

Dishion also reminded the workshop participants of the success demonstrated by programs such as Big Brothers and Big Sisters of America (see Chapter 7), which provide children and adolescents with positive role models.

On the topic of peer leaders, Catherine Bradshaw of the University of Virginia Curry School of Education noted another sort of challenge—that the youth who are volunteering for leadership roles may not be particularly influential in their peer groups. Sometimes they have a history of victimization or are from a marginalized group, she said, although they can achieve more status as they get older.