3

Targets of Bullying and Bullying Behavior

Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- Ethnic minority middle-school students generally feel safer and less bullied in more diverse contexts, perhaps because they perceive peer mistreatment as a sign of prejudice and do not blame themselves in the same way that majority students do. (Juvonen)

- Having one friend lowers the risk of being bullied, and even a neutral social interaction can help re-establish a sense of connection after being bullied. (Juvonen)

- Bullying has been associated with direct and indirect exposure to family violence and with sexual harassment and teen dating violence during adolescence. (Espelage)

- Many of the students who engage in bullying are found to be near the center of dense social networks, and aggression tends to stay within social categories. (Faris)

- Genetics research, neuroimaging, studies of the stress hormone cortisol, and investigations of chromosomal changes all have revealed harmful biological changes associated with bullying. (Vaillancourt)

Bullying can be analyzed at different levels, from the sociological to the genetic. In the initial panel of the workshop, four presenters summarized research on students who bully others and on the targets of bullying from four different perspectives and then, in the discussion period, explored possible ways in which these perspectives could be integrated.

CONTEXTUAL EFFECTS ON THE TARGETS OF BULLYING

“Why are we concerned about bullying?” asked Jaana Juvonen, professor in the developmental psychology program at the University of California, Los Angeles. Is it because of its prevalence or because of the negative effects on the targets of bullying? The answer, in all likelihood, is both, she said. But when the effectiveness of interventions is examined, the focus is on prevalence and related factors, such as improvements in school climate. These outcomes are undoubtedly important, but Juvonen said that she was unable to find, in preparing for the workshop, even one study that examined whether anti-bullying efforts help alleviate the emotional pain and the health consequences for the most vulnerable—those who experience bullying repeatedly.

To create environments that protect the chronically bullied, it is necessary to understand how bullying-related distress varies across contexts and situations, Juvonen said. First, the emotional distress of the targeted varies across individuals. This variation is usually attributed to individual differences among the targets of bullying. For example, those who show more distress may be seen as lacking emotion-regulation abilities, being more sensitive to rejection, or not having good coping strategies, Juvonen said.

Much less is known, Juvonen said, about the role of social context. For example, how does group composition or the relationships in a particular context make the pain of bullying either greater or less? To address this void in the research, Juvonen and her colleague Sandra Graham have been investigating features of the social environments of school-based bullying to try to understand the links between bullying experiences and emotional distress. Specifically, they have compared the plight of targets of bullying across schools that vary in ethnic composition, with a focus on environments in which students feel safe as opposed to unsafe.

Comparing schools in California with varied ethnic compositions, they found that African-American and Latino middle-school students generally felt safer and less bullied in the more diverse contexts (Juvonen et al., 2006). However, Juvonen asked, although diversity may be protective for at least some groups or individuals, is there safety in numbers of similar others when bullied? Peer groups become increasingly ethnically segregated across grades, suggesting that same-ethnic peers are an important reference

group. The question, then, she said, is whether the plight of a target may vary depending on the size of his or her ethnic group.

In this case, Juvonen and her colleagues examined social anxiety and found a stronger association between victimization and social anxiety when the victims of bullying had a greater number of same-ethnic peers (Bellmore et al., 2004). Similar findings were obtained for loneliness, she said. Thus, being bullied was more strongly associated with both social anxiety and loneliness when students were in settings with greater (as opposed to fewer) same-ethnic peers.

This finding raises the question of how targets construe their plight. When youth are bullied, Juvonen observed, they are likely to ask, “Why me?” Answers to this question—that is, the attributions they make—are likely to affect the level or type of distress they experience.

Using the construct of characterological self-blame—the idea that targets come to blame themselves and believe that there is nothing they can do about it—Juvonen and her colleagues looked at why students who belong to majority groups in their school would feel worse. They found a stronger association between getting bullied and self-blame when the students belonged to the numerical majority (Graham et al., 2009). In contrast, no association was found between bullying and self-blame when the students belonged to the numerical minority in their schools. Recent evidence suggests that those who are in the numerical minority perceive this kind of peer mistreatment as reflecting prejudice on the part of their peers and do not blame themselves in the same way that those who belong to the numerical majority, Juvonen said.

To further understand the role of characterological self-blame, Juvonen and her colleagues have more recently examined its potential role in prolonging bullying. Focusing on the first year in middle school, they looked at which youths bullied in the fall continued to be targeted by the spring of sixth grade. The question was whether self-blame functions similarly to depression—as both a consequence and a risk factor of victimization. They found support for indirect associations, in that children who had been targeted in the beginning of sixth grade were more likely to continue to be bullied throughout the school year if they self-blamed and become depressed (Schacter et al., 2014).

These analyses suggest that contextual factors affect how children interpret their mistreatment and that self-blame is especially detrimental, Juvonen said. They also suggest that to alleviate distress and reduce the duration of bullying, interventions may need to change targets’ attributions of their plight.

The Power of Friends

Juvonen concluded her presentation with “something a little more positive.” A particularly potent protective factor against bullying, she said, is having friends. Although the type of friend matters, good evidence suggests that having even one friend lowers the risk of being bullied. Moreover, when a student is bullied, his or her distress can be alleviated by having that one friend, Juvonen said.

Two recent dissertation studies from her laboratory provide further insights about these findings, suggesting that the effect may result not from individual differences in whether children have friends but from social replenishment after peer mistreatment. In the first study, Guadalupe Espinoza showed that when an individual experienced cyberbullying, time spent with friends—not the quality of the friendship—alleviated the intensity of distress reported by high school students (Espinoza, under review). If, on the day a student was cyberbullied, that student spent some time with a friend, stress was significantly and substantially alleviated, Juvonen said.

In the second study, Elisheva Gross varied the activities of youth who were excluded in an online experiment: They were randomly assigned either to instant message with an unknown peer or to play a solitary computer game. The goal was to document recovery from self-esteem loss related to the exclusion experience. What she found was that recovery was much quicker for those who had a chance to interact with an unknown peer as opposed to playing a solitary computer game (Gross, 2009). These findings suggest that recovery does not even “require” having a friend but just connecting with a peer, Juvonen observed.

This research has helped identify two possible antidotes to bullying that can vary across situations and contexts, Juvonen said. The first is to realize “It’s not just me” in thinking about bullying. The second is to recognize that even a neutral social interaction can help reestablish a sense of connection after being bullied. It is important to realize that environments make youth socially isolated, Juvonen said. Youth are not socially isolated unless other people ignore or exclude them, she said, which is why a school environment that fosters connectedness is critically important.

ASSOCIATIONS AMONG BULLYING, SEXUAL HARASSMENT, AND DATING VIOLENCE

Bullying is not an isolated behavior, observed Dorothy Espelage, Edward William Gutgsell and Jane Marr Gutgsell Endowed Professor in the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. For example, several cross-sectional and a handful of longitudinal studies link direct and indirect exposure to family violence

with bullying behavior (Espelage et al., 2000, 2013; Voisin and Hong, 2012). Bullying is also predictive of sexual violence during adolescence, and the two share similar risk factors (Basile et al., 2009; Espelage et al., 2012). In addition, Miller et al. (2013) demonstrate how dating violence and bullying often co-occur, highlighting the need to recognize the interrelatedness of these behaviors.

However, few longitudinal studies have unpacked the mechanisms from the contextual variables of bully perpetration, Espelage said. Even fewer longitudinal studies have considered how bully perpetration is associated with the emergence of gender-based bullying, sexual harassment, or teen dating violence during early adolescence.

Espelage and her colleagues (2014) have proposed a developmental model of bullying, sexual harassment, and dating violence. To test this model, they tracked 1,162 racially and economically diverse students from 2008 to 2013. The students were in three cohorts—fifth, sixth, and seventh graders in 2008—with seven waves of data collection occurring during the years of the study.

One takeaway message from this research, Espelage said, is that homophobic name-calling and unwanted sexual commentary are prevalent in middle school. “It takes about 3 minutes when you go into a middle school to hear this kind of language,” she said. Youth who engage in bullying behavior resort to homophobic name-calling over the middle-school years (Espelage et al., 2012, in press). Boys and girls may try to demonstrate their heterosexuality by sexually harassing others. Bullying and homophobic name-calling may also promote unhealthy dating relationships, she said.

This has been a powerful finding for teachers and administrators, who say that they often hear this language. Bullying prevention programs need to include a discussion of language that marginalizes gender non-conforming and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth, Espelage said, despite the potential backlash from those who see such discussions as promoting an alternative sexual orientation.

Espelage’s research also has demonstrated that bullying and homophobic name-calling is associated with later sexual harassment (Espelage et al., in press). As students transition to high school, a strong connection emerges between bullying and sexual harassment, she said. In addition, sexual harassment, unwanted sexual commentary, and unwanted touching predicted teen dating violence, including verbal, physical, and sexual coercion.

This research is predicated on a social–ecological model and a social–interactional learning model in which family violence serves as an important context for understanding the relations among bullying perpetration, sexual harassment perpetration, and teen dating violence, Espelage explained. The researchers have tested this model by evaluating the changing influence of key social agents across early to late adolescence. For example, in the

dataset discussed by Espelage at the workshop, 32 risk and protective factors were considered. Girls were separated out because of the tremendous variability in the ways in which they report bullying perpetration and exposure to family conflict and sibling aggression. On this last point, Espelage noted that sibling aggression is emerging as a potent predictor of bullying involvement for both perpetration and victimization. For boys, family conflict did not predict bullying perpetration, just sibling aggression. “Sibling aggression, which many of us feel is a proxy in some ways for violence in the home, was an important predictor here as well,” Espelage said.

Possible Next Steps

From this research, Espelage offered several suggestions. Future research will need to consider multiple contexts to identify longitudinal predictors, mediators, and moderators associated with outcomes for youth who engage in bullying behavior, she said. “We must begin to think much more creatively about incorporating discussions of gender-based name-calling, sexual violence, and gender expression.”

In addition, Espelage said there is a need to examine and respond to various forms of interpersonal violence as a part of prevention of bullying and youth violence. In particular, Espelage pointed to exposure to family violence and teen-dating violence victimization and perpetration. Such research could evaluate the changing influence of key socializing agents across early to late adolescence and examine the antecedents, correlates, and sequelae of bullying, sexual harassment, and teen dating violence, she said.

Finally, Espelage said that there is a need for comprehensive, social–ecological longitudinal studies to understand the complex developmental unfolding of different types of youth violence. The effect sizes for many bullying prevention programs have been low and have even been negative for some programs in high schools, partly because programs designed for elementary school children are being used inappropriately for older students (Yeager et al., in press). “We need to be developmentally sensitive to the types of experiences kids are reporting,” Espelage said.

INSTRUMENTAL AGGRESSION

The research literature on bullying suggests that individuals who engage in bullying behavior have two contradictory attributes, said Robert Faris, associate professor of sociology at the University of California, Davis. On the one hand, bully perpetrators would seem to have substantial forms of maladjustment, such as troubled home lives or challenging psychological dispositions, which would imply that they are on the fringes of social net-

works and do not have high status. On the other hand, he said, bullying would seem to be a way of building status by establishing one’s place in a social hierarchy.

Faris’s own research suggests that both of these observations are accurate. “I find a lot of evidence to suggest a very traditional perspective of maladjusted kids who are picking on those who are weaker than them,” he said. “I also found a second pattern,… which is instrumental aggression.”1 When the social connections among students in a high school are diagrammed, many of the students who engage in bullying are found to be near the center of dense social networks, Faris said. Connections between individuals who engage in bullying behavior and their targets tend not to occur around the perimeter of social networks, as the early work on bullying would suggest (Faris, 2012). “What we see is a preponderance of ties originating within the core of these networks among the more popular kids,” he said. “I think this is evidence of an instrumental pattern of aggression.” Working with Susan Ennett, Faris has also done research on the role of status motivation. They found that students who want to be more popular are more aggressive (Faris and Ennett, 2012). They also found that students, regardless of how much they care about popularity themselves, are more likely to be aggressive if they have friends who care about popularity. In addition, they found that the highest rates of aggression occur between pairs of students who are both high status, not between high-status and low-status students. “To me that is consistent with the idea of competition for status and the use of aggression to those ends,” Faris said.

Social Distance

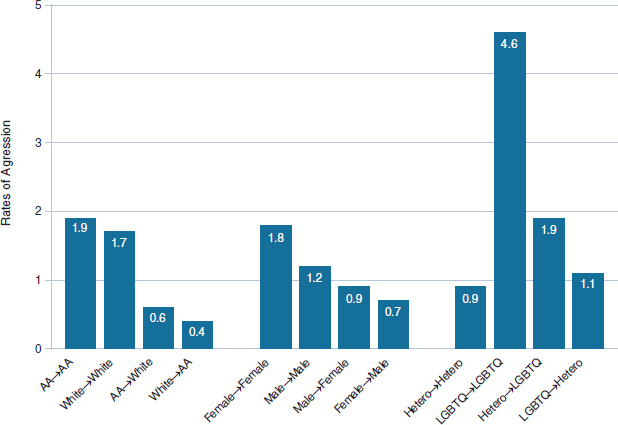

Instrumental aggression also depends in part on social distance.2 Aggression tends to stay within social categories, Faris said. For example, the highest rates of aggression tend to be within race and not across race. His data indicate that bullying has a very low likelihood of crossing racial lines.

The situation with gender is similar: The highest rates of aggression are between girls and between boys rather than across gender lines. Although boys and girls have roughly equal rates of aggression, both boys and girls target girls more often than they target boys, which results in girls being disproportionately targeted, Faris said.

__________________

1 Instrumental aggression refers to purposive aggression intended to achieve some goal, particularly higher social status.

2 Social distance can refer to fundamental demographic barriers (e.g., racial divides) and, in social network terms, to the number of friendship links separating two people in a social network (e.g., a friend of a friend is distance 2).

Working with a different dataset, Faris and his colleagues found very high rates of aggression among adolescents who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning (LGBTQ) as well as the more traditional pattern of heterosexual students bullying LGBTQ youth at a relatively high rate (see Figure 3-1). Again, he said, bullying often occurs within social demographics.

Faris said that a similar conclusion also emerges from analyses of friendship networks. Rates of bullying drop dramatically as young people become farther apart socially. A lot of aggression occurs within friendship groups and even between friends, Faris said. This can lead to some complicated dynamics. For example, preliminary evidence suggests that when friends have an aggressive event, they cease to become friends. But when two students who are not friends are aggressive toward each other, they have a greater likelihood of becoming friends at some point in the future. “There is a cycle of conflict that is going on,” Faris said “Allegiances are being formed and broken up.”

Cyberbullying appears to exhibit the same patterns, Faris said. Relatively high-status students are more likely to target each other.

FIGURE 3-1 Aggression rates are higher within race, gender, and sexual orientation categories than across categories.

NOTE: AA = African American; LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning.

SOURCE: Faris presentation, 2014.

In a recent paper, Faris and his colleagues looked at five different outcomes of victimization: anger, anxiety, depression, attachment to school, and centrality in social networks, which they referred to as status (Faris and Felmlee, 2014). They found that the victims who were high status had a more adverse reaction to aggression. When high-status students are victimized, their anger, anxiety, and depression increase much more dramatically than is the case with lower-status students, and they drop in status much more than do low-status students—an effect that is also seen with students who are in the middle of social hierarchies. By the time students reach high school, a given act of bullying is not necessarily going to transform the sense of self of a low-status student, Faris said, but “a kid who may have struggled mightily to reach a lofty social position might experience a little more distress. They may feel that they have more to lose.”

Is Bullying Instrumental?

The final issue Faris discussed was whether bullying is effective if it is considered as instrumental. The data suggest that victims of bullying do lose status. In addition, using yearbook data to provide additional measures of social status, Faris and his colleagues found that aggressive behavior predicted a significant increase in social status by the end of high school, but it depended partly on whom was targeted (Faris, 2012). “They had to go after kids who were socially close, kids who were themselves aggressive, or kids who were high status themselves,” he said. “They had to pick the right targets to receive a social boost. Again, I think this all fits a picture of aggression as at least potentially useful for climbing social ladders.”

In general, these data point to a relatively poor quality of friendships among high school students and adolescents, Faris said. As an example of these poor-quality friendships, he noted that if students are asked to name their eight best friends, only 37 percent of those ties are reciprocated. Furthermore, when Faris and his colleagues asked students to name their five closest friends every 2 weeks, they found high rates of turnover in those lists.

“This is a symptom of a problem,” he said. “It is related to this process of competing for status. If we thought about ways of helping kids develop stronger, more robust friendships and perhaps fewer of them, I think that might help build resilience.”

Many young people do not recognize what a good friend is and do not know how to be a good friend, Faris said. Parents and other adults can help teach these lessons, he said, and schools could be reorganized to offer activities that can foster interest-based friendships, as opposed to their traditional organization of offering just a few prestigious activities, he suggested.

THE BIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS ASSOCIATED WITH BULLYING

Some youth fare poorly when they are bullied, and some do better. It is important to understand the moderators and mediators behind this variability, said Tracy Vaillancourt, a professor and the Canada Research Chair in Children’s Mental Health and Violence Prevention at the University of Ottawa. For example, she said, some evidence suggests that girls are profoundly affected by being socially excluded, while boys are more affected by being physically abused by their peers. Social support also matters. For example, children who are targets of bullying at school and also experience bullying at home tend to have poorer outcomes. In addition, temperament is associated with how people cope with stress, in that some people are more agitated over time, Vaillancourt said.

Less attention has been paid to the biological moderators and mediators that are associated with bullying at a physiological level, Vaillancourt said. She summarized research in four areas of “how bullying gets under the skin to confer risk.”

Genetic Evidence

Genetic evidence suggests that biology may confer a risk for poorer outcomes. Caspi et al. (2003) found that a polymorphism of a serotonin transporter gene influenced the likelihood of a person being depressed at age 26 after having been severely maltreated, probably maltreated, or not maltreated in childhood. Those who had been severely maltreated and who had two short alleles for the gene had a depression rate of about 70 percent at age 26, while those who had been severely maltreated and who had two long alleles had no greater odds of being depressed at age 26 than children who had been treated well by their caregivers, Vaillancourt said.

This study has been replicated within the context of peer abuse, Vaillancourt said. Looking at girls who have been relationally victimized by their peers, Benjet et al. (2010) found that having the short allele of the gene conferred a risk of depression that was three times greater than having the long allele. “I can’t think of something that confers such a strong risk,” Vaillancourt said. This “is a really powerful finding.”

Neurophysiological Evidence

People who have experienced bullying often use physical pain metaphors to describe the social pain they feel. Such comments as, “It felt like somebody punched me in the stomach,” or “It broke my heart when they said that to me,” are common, Vaillancourt said.

Neuroscience points to an overlap between social and physical pain,

Vaillancourt said. For example, Chen et al. (2008) found that people can relive and re-experience social pain more easily than physical pain and that the emotions they feel are more intense and painful than the experience of physical pain. “Physical pain is short-lived, whereas social pain can last a lifetime,” Vaillancourt said. “Think about when you were in grade six and you were excluded or ostracized. Then think about the time when maybe you broke your ankle. When you think about breaking your ankle, you don’t get a visceral reaction to recalling the event. When you recall the event of being excluded by the peer group, it is as if you are living it today.”

Neuroimaging studies show that parts of the cortical physical pain network are activated when a person is socially excluded (Masten et al., 2009). The same areas of the brain that are activated when a person stubs a toe are activated when that person is called stupid or is not invited to a party, Vaillancourt said.

Similarly, children may be hypersensitive to rejection, Vaillancourt said. Crowley et al. (2009) found that 12-year-olds could recognize being rejected in less than 500 milliseconds. “We have this radar… to not being included,” she said, which might have its roots in some evolutionary advantages in mammalian species.

Neuroendocrine Evidence

A large amount of research has examined the hypothalamic/pituitary/ adrenal (HPA) axis, or the human body’s stress system, Vaillancourt said. One product of that stress system is cortisol, which has been used as a biomarker of dysregulation of the HPA axis—that is, of impairments in the normal functioning of the HPA system.

When people are stressed, they produce more cortisol, which has been shown to have detrimental effects on the brain, Vaillancourt explained. However, she added, when people face extreme and prolonged stress, cortisol levels tend to be lower than normal, perhaps because receptor sites are damaged from cortisol overproduction.

A variety of studies have demonstrated a link between peer victimization and dysregulation of the HPA axis, Vaillancourt said. Dysregulation of the HPA axis has also been shown to be related to disruptions in neurogenesis, or the growth of new brain cells, resulting in poorer memory. For example, Vaillancourt et al. (2011) found that children who were victimized by their peers became depressed, and this depression led to changes in the HPA axis. The dysregulation of the HPA axis led in turn to memory deficits, particularly in areas that are sensitive to the effects of cortisol. “One of the things that we know about kids who are bullied is that they don’t do as well in school,” Vaillancourt said. “A lot of times we think that perhaps it has to do with the fact that they are distracted by being bullied, [but] perhaps

the effects of being bullied are affecting their memory, which then changes their academic profile and outcomes.”

In a study of whether changes in the HPA axis are actually caused by having been bullied, Ouellet-Morin et al. (2011) looked at pairs of identical twins, one of whom experienced bullying and the other of whom did not. The researchers showed that these childhood experiences had a causal effect on the neuroendocrine response to stress. “It is not the case that kids get bullied because for some reason the peer group picks up on the fact that their HPA axis is different and that they are dysregulated. They become dysregulated as a function of being bullied,” Vaillancourt said.

Telomere Erosion

Finally, Vaillancourt described the erosion of telomeres, which are repetitive DNA sections at the ends of chromosomes that promote chromosomal stability and help regulate the replicative lifespan of cells. The length of telomeres is linked to normal processes such as aging and is associated with such health behaviors as smoking and obesity. “Your telomere gets shorter and shorter the longer you live and the more bad things you do,” Vaillancourt explained.

Shalev et al. (2013) recently found that exposure to violence during childhood, including bullying, was associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age. These changes could alter a person’s developmental or health trajectory through epigenetic mechanisms and explain, for example, why one sister develops breast cancer while her twin sister does not, Vaillancourt said.

Changing Health Trajectories

Understanding the biological underpinnings of how peer relations affect emotional and physical health can help legitimize the plight of peer-abused children and youth, Vaillancourt concluded. It can also cause policy makers and practitioners to prioritize the reduction of school bullying. These kinds of findings “urge us to really get going,” she said, because bullying and bullying prevention can change children’s health trajectories.

INTEGRATING PERSPECTIVES

During the discussion period, several questions centered on the issue of integrating the different perspectives offered by the four presenters in this session. In response to a question on this subject, Vaillancourt said that one of her motivations in studying bullying is to prevent the targets of bullying from being re-victimized by educators who think that they are at fault and

just need to be tougher. If some students are shown to be biologically more susceptible to the negative effects of bullying, then principals, parents, and other adults may be less likely to blame the targets of bullying and more likely to protest strongly when students are bullied.

Vaillancourt also described recent epigenetics research that points to changes in the expression of genes as a consequence of environmental influences, including early adversity. “We have failed to recognize that the stress of being bullied by our peers, which interferes with our fundamental need to belong, would be equivalent to living in a house where you are abused by your caregiver,” she said. “It would be equivalent to living in extreme poverty.” The study of epigenetic effects caused by such experiences may be a way to understand mental and physical health trajectories. “We all need to come together and intersect our knowledge bases so that we can be better informed in preventing this,” she said.

Espelage said that her longitudinal study found that not only was bullying perpetration predicted by family violence but also bully perpetration and victimization were associated with the later onset of alcohol and drug use in the victims (Espelage et al., 2013; Rao et al., in press). Faris observed that the victims of bullying are more likely to turn to substance use as a way of coping.

The moderator of the panel, Catherine Bradshaw of the University of Virginia, speculated that aggressors may be picking up on the emotional vulnerability of some individuals and targeting them and that students who are less affected by bullying may be less attractive targets. Perhaps individuals engaging in bullying behavior use social cues and the reactivity of other students to choose targets, Bradshaw suggested.

Vaillancourt pointed to recent research on how the presence or absence of power affects the brain (Hogeveen et al., 2014). When a subject is afforded power, he or she pays less attention to and is less aroused by others. At the neurological level, those who hold power are less sensitive to the plight of others. Those who do not hold power are much more aware of the environment and the distress signals of others, Vaillancourt said.

One of the youth panelists, Glenn Cantave, a junior at Wesley University, noted that when he was younger he was more sensitive to the attacks of bullies, but he has since developed a “thicker skin.” Does that, he asked, imply some sort of tolerance to stress that perhaps would be related to cortisol levels?

Vaillancourt responded that the offspring of Holocaust survivors have lower cortisol levels, even though they did not experience the trauma of the Holocaust themselves. Perhaps such lower cortisol levels are a protective adaptation that acts to reduce the risks associated with chronically high cortisol levels, but the actual mechanisms behind the lowered cortisol levels are still not well understood. For example, Vaillancourt said, almost every

study of children who have been bullied finds that they have low cortisol, whereas their longitudinal studies showed first high levels and then low levels, suggesting that the dysregulation of cortisol is a more important factor to look for than absolute levels. Longitudinal studies of the HPA axis over time across different stressors could reveal some of the mechanisms behind these complex patterns, she suggested.

Vaillancourt also referred back to the relationship between depression and being bullied. The depression often comes first, suggesting that the lack of engagement among depressed young people may make them more vulnerable to victimization. Again, she said, longitudinal studies would help explain the observed heterogeneity in trajectories and outcomes.

Basing interventions on the social organization of schools may be a way to integrate knowledge in practice. For example, Espelage pointed out that a better approach than universal programs for sexual violence and rape prevention might be to identify students who have the greatest social capital and train them to be attitude changers, drawing on what is known from industrial and organizational psychology. Bystander intervention programs have been shown to produce large effect sizes in promoting positive bystander behaviors (Polanin et al., 2012), she said. Another promising approach is to work with teachers to understand the networks and hierarchies in their classrooms.

Juvonen agreed that focusing on bystanders is an especially promising way of changing the high status of individuals who engage in bullying behavior. “Bullies love the audience,” she said. “They want not only a reaction from their victim, but they also live for the fact that everybody else is in awe and joins the bully rather than the victim. It is those dynamics that need to be changed.” One way to turn this around, Juvonen suggested, may be to emphasize to students the rights that they have, one of which is the right to come to school and not be afraid.

Juvonen also pointed out that teachers and administrators know who the lowest-ranking individuals are—and thus have a good idea of those who are at highest risk for victimization—yet not many schools offer proactive remedies for these students. Instead, a wise librarian or well-liked teacher might keep a door open after lunch. A better option, Juvonen said, would be a lunchroom that brings people together with specific interests. “We have a lot of smart teachers and educators out there who are doing little things that can make a huge difference.”