Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- As of 2014, 49 states and the District of Columbia have enacted anti-bullying laws, whose key components range widely. But little is known about the extent to which the laws and their implementation actually decrease bullying behaviors. (Hatzenbuehler)

- One Oregon study suggests that “inclusive” anti-bullying policies—those that specifically include sexual orientation as a protected-class status—reduce the risk of suicide attempts and peer victimization in gay teenagers. (Hatzenbuehler)

- Student-on-student bullying victimization can be perceived as imposing a learning disability on the targeted children because victimization creates barriers to their education. (Abrams)

- Schools face strong disincentives against enforcing state-mandated anti-bullying laws, including the risk of costly lawsuits brought by bullies and their parents claiming infringement of First Amendment speech rights. But, unlike speech, physical assaults and true threats are not protected under the law. (Abrams)

- Existing law puts school districts in a strong legal position to impose discipline in student-on-student bullying cases, but districts seeking to protect targeted students must defend lawsuits that might arise. (Abrams)

As student-on-student bullying has received greater attention in recent years, state legislatures have responded. Forty-nine states and the District of Columbia now have laws against bullying. Evaluation is critical for understanding a law’s impact, how it ends up being enforced, and any unintended consequences of enforcement. Two speakers provided an overview of anti-bullying laws and policies, including how attempts to prohibit bullying fit within a broader legal framework that addresses children’s issues.

MANY ANTI-BULLYING LAWS EXIST, BUT ARE THEY EFFECTIVE?

The United States has seen a rapid proliferation of anti-bullying laws, with state legislatures enacting or amending more than 120 bills on bullying and related behaviors between 1999 and 2010. As of 2014, 49 out of 50 states have laws to prevent bullying, said Mark Hatzenbuehler, assistant professor of sociomedical sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. The lone exception is Montana, which does, however, have an anti-bullying policy, he said.

Scholars have developed conceptual frameworks for understanding the content and scope of laws and policies that target bullying behaviors (Limber and Small, 2003; Srabstein et al., 2008; U.S. Department of Education, 2011). In a 2011 report, the U.S. Department of Education developed a comprehensive framework to evaluate anti-bullying laws and policies in 46 states. The report identified 16 key components found in the existing laws, such as a definition of what bullying is; a list or “enumeration” of the specific groups of individuals to be protected from bullying; and requirements for communicating the law or policy to school administrators, teachers, and students. Some key components were more common than others. For example, 43 states included descriptions of bullying behaviors that are prohibited, but only 17 states enumerated protected groups. About one-third of states included at least 13 to 16 of the components, noted Hatzenbuehler.

The vast majority of research on anti-bullying legislation has focused on legal content analyses, Hatzenbuehler said, but “we know very little about the extent to which these policies are actually effective in meeting their stated goal.” He and Katherine Keyes of Columbia University conducted one of the first empirical studies to look at the effectiveness of these policies (Hatzenbuehler and Keyes, 2013). They investigated whether having an “inclusive” anti-bullying policy—one that specifically includes sexual orientation as a protected class—reduced suicide risk and peer victimization (being aggressively targeted by other children) in lesbian and gay youth. Focusing on 34 counties in Oregon that had anti-bullying policies, the researchers examined 197 school districts to determine whether those policies at the district level included sexual orientation as a protected-class

status. In only 15 percent of the Oregon counties did all their school districts have inclusive anti-bullying policies, Hatzenbuehler said.

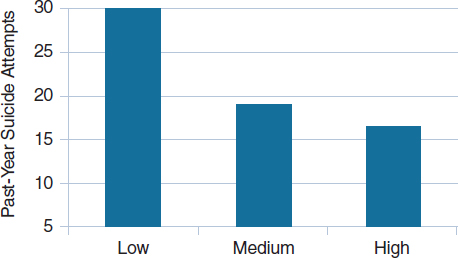

The researchers linked these findings on anti-bullying policies to health and sexual orientation data collected through an annual survey of 11th-grade public school students in Oregon, including 301 lesbian and gay youth. Counties were divided into three categories ranging from “least inclusive” to “most inclusive” based on the proportion of their school districts with anti-bullying policies that included sexual orientation. Results showed that around 31 percent of lesbian and gay youth living in the least inclusive counties had attempted suicide in the past year—twice as many as the 16 percent of gay and lesbian teens who attempted suicide in the most inclusive counties (see Figure 9-1). “We find that policies that do not include sexual orientation as a protected class are not protective of lesbian and gay youth in terms of reducing the risk of suicide attempts,” Hatzenbuehler said. Inclusive anti-bullying policies were also associated with a reduced risk for peer victimization for all youth, not just gay and lesbian youth.

Hatzenbuehler noted that research on the effect of anti-bullying policies is consistent with other studies that document the impact that public policies have on health and behavioral outcomes (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009, 2010, 2012). Hatzenbuehler suggested that this is noteworthy in that it offers precedence for considering laws and public policies as one of a number of effective strategies that can be used to improve the health and well-being of young people. However, much more research is needed to study the actual effectiveness of policies in reducing bullying behaviors to establish

FIGURE 9-1 Counties in Oregon with more inclusive anti-bullying policies have the lowest risk of suicide attempts among lesbian and gay youths. SOURCE: Hatzenbuehler and Keyes, 2013.

best practices for policy makers and school administrators, Hatzenbuehler said, including stronger methodologies for establishing cause-and-effect linkages. It is often unethical to conduct randomized controlled trials that would assign individuals to live in environments with or without an anti-bullying policy, he noted, but longitudinal and quasi-experimental studies can be used instead. Researchers can also take advantage of the heterogeneity in anti-bullying laws to see whether states with the more comprehensive policies have more success in reducing bullying.

If anti-bullying policies are in fact protective, Hatzenbuehler added, then experts should be studying why they work (by examining mediating factors) and for which groups of people they are most effective (by testing moderators). For example, reducing peer victimization appeared to be one of the mediating factors in Hatzenbuehler and Keyes’ study. More studies are also necessary to understand the effects of putting anti-bullying laws into practice on the ground, he said. Qualitative and ethnographic studies in schools with administrators, teachers, parents, and youth could help identify barriers and facilitators in implementation, he added.

To start to address some of these critical gaps, Marizen Ramirez of the University of Iowa is conducting a longitudinal study to evaluate the implementation and outcomes of anti-bullying legislation in her state. Hatzenbuehler and Ramirez are also analyzing the legal content of anti-bullying legislation in several key U.S. regions and linking those findings to Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance data to see whether stronger laws against bullying are more effective in reducing bullying behaviors.

HOW THE LAW BOTH HELPS AND HINDERS THE PROTECTION OF CHILDREN FROM BULLYING

To further describe the legal framework for anti-bullying regulations, Douglas E. Abrams, a professor at the University of Missouri School of Law, discussed the private and public system that protects children. The pediatric safety system has parents at the top of the hierarchy and works its way down through the public schools, law enforcement, juvenile and family courts, and state mental health agencies (Abrams, 2009). Abrams focused his remarks primarily on the public school system, because, he said, most aggressors know their victims through attending school and do not foresee that anyone but classmates will pay much attention.

Abrams highlighted the three P’s of school anti-bullying efforts: perceptions, prevention, and potential legal constraints. Public policy often depends on perceptions, he said. Bullying victimization can be perceived as imposing a learning disability on child victims, he said, because it creates barriers to education similar to those identified by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (Abrams, 2012, 2013). “Bullying victimiza-

tion jeopardizes the state’s obligation to provide a free public education to all children,” he added. The IDEA recognizes disabilities that arise from external circumstances that are very similar to bullying victimization: “Students cannot learn effectively when they are scared stiff in school,” Abrams said. Such a perception of bullying’s effects could motivate legislatures to act effectively; even though 49 states have anti-bullying laws, amendments are still necessary to ensure that policies work effectively, he said.

Legal Constraints

Turning to potential constraints, Abrams cautioned that when it comes to bullying, “we need to be wary of legal solutions, which are often not useful solutions at all.” States cannot prosecute, adjudicate, or discipline their way out of the bullying problem, he said, because “there is just too much bullying going on.” Prosecution and juvenile court adjudication are reactive measures invoked only after somebody is already hurt. Public authorities serve children best when they can modify behavior in a preventive mode without turning to formal processes except in the most serious cases, he said.

Abrams offered three conclusions on potential legal constraints. First, he said, “the law can sometimes present major challenges to protecting bullied children.” Schools may face strong professional and financial disincentives against enforcing state anti-bullying laws. Second, when bully perpetrators or their parents file lawsuits, they typically assert constitutional rights or other legal rights. Third, existing law puts school districts in a potentially strong position if they present a good case on the facts in student-on-student bullying cases, he said, but lawsuits will occur and victory is not assured.

All enforcement of state anti-bullying laws is ultimately local and depends on teachers, administrators, and others in the school building, Abrams explained. For one thing, statewide anti-bullying laws are almost always unfunded mandates, he said, so the question becomes, Who pays for implementation and enforcement? To conform with state anti-bullying laws, cash-strapped school districts have to pay to hire and train faculty, Abrams said, but he added that he nonetheless thinks that such endeavors can be cost effective. The greatest cost that school districts must bear related to anti-bullying efforts is defending against the litigation that can arise in reaction to those efforts, he said. It is not always easy for courts to determine who did what to whom, which means that judges tend to have a great deal of discretion in deciding such lawsuits. As a result, Abrams said, teachers and administrators may find that “sometimes the path of least resistance is to turn their backs on student misconduct.”

Concerning the legal authority to implement anti-bullying efforts, Abrams said that public schools are in a potentially strong position. In

the court’s eyes, he said, schools are “special places” when it comes to discipline: The constitutional rights of elementary and secondary students inside public schools are less than their constitutional rights outside school because courts must weigh the need to protect students in school.

The seminal decision regarding students’ constitutional rights in school, Abrams said, was from the 1969 case Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District in which the plaintiffs wore black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. The Supreme Court held that a school may discipline students for speech that “materially or substantially disrupts school activities” or that creates a “collision with the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone,” Abrams explained. Another relevant decision, Bethel School District v. Fraser in 1986, involved a high school student who delivered a lewd speech in a school assembly program and later filed suit claiming that his resulting suspension violated his First Amendment speech rights. The Supreme Court held, Abrams said, that schools may regulate student speech to teach “the shared values of a civilized social order” and fundamental values, which include consideration of “the sensibilities of fellow students” and “the boundaries of socially appropriate behavior.”

Many cases of bullying, including cyberbullying, also involve physical assaults, Abrams noted, and these are not protected under the law. The First Amendment does not protect true threats of violence, even verbal ones. Assaults, Abrams explained, may include pushing, shoving, spitting, and throwing a pencil at someone.

Anti-bullying legislation cannot protect school districts from lawsuits, Abrams said, but schools can prevail if they present the right kind of evidence. He emphasized that anti-bullying legislation and policies are not particularly valuable if schools are reluctant to exercise their disciplinary authority. School districts must be willing to fight lawsuits to protect students, he said.

Although 49 states have anti-bullying laws, some legislatures still have much work to do in the arena of cyberbullying, Abrams said. Most states require school districts to have policies banning cyberbullying, for example, but these statutes typically apply only to discipline imposed for what a child does in the school building, on school grounds, or on a school bus or school-sponsored trip. However, Abrams said, almost all cyberbullying is done off campus. Still, many perpetrators of cyberbullying eventually end up committing physical assaults, so schools may discipline them for those actions, he said.

LEGAL RESPONSES TO BULLYING

During the discussion period, one questioner asked how attorneys can work with schools to encourage the implementation of new anti-bullying policies. Abrams suggested that lawyers can assure that procedures for handling bullying situations meet constitutional and nonconstitutional guidelines and that administrators carefully document their actions against bully perpetrators. In addition, he said that while school districts generally tend to lose many student free-speech cases outside the bullying area, courts do not actually require much evidence to establish that a disruption in school has been material and substantial. “If two students fight or assault one another in a classroom, that is Tinker-type disruption, which ought to win for the school district if the perpetrator can be identified,” he said. If lawyers put on a good case, showing how much time teachers and schools spend dealing with animosities arising from bullying and how hurtful bullying is to students, he said, “I think the judges would be receptive.” However, he added, school districts often fail to put on a proper case.

Jonathan Todres of Georgia State University College of Law asked if it is possible to address social harms such as bullying in ways that incentivize positive behavior rather than just punish bad behavior. Hatzenbuehler replied that anti-bullying policies that enumerate specific protected groups encourage better behavior by fostering more diverse, inclusive environments in schools. Researchers do not have a good handle on which types of policies—punitive versus positive reinforcement—are better at deterring bullying; that is an empirical question that needs examination, he said.

Dorothy Espelage of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, asked the speakers what advice they could give for parents who call in saying that their child is being chronically victimized, beyond telling them to document everything carefully or to move their child out of the school? Espelage noted that in a number of cases where bullied children committed suicide, parents sued school districts and lost; the districts had hired psychologists who testified that the child’s suicide was due to having depression and not due to any harassment by bullies or negligence by the schools.

Abrams replied that it is hard to know what to tell parents, especially because it is not always clear to school administrators and teachers what the appropriate remedy is in a particular case. Parents may have to choose from among some bad alternatives to try to make a victimized child’s life better, Abrams said. Hatzenbuehler added that judges in some cases involving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth have been open to hearing social science research data on how bullying can affect these teens. Abrams also noted that federal civil rights statutes might apply if the bullying victim was targeted because of religion, race or ethnicity, or sexual orientation.