“Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors should be understood as acts of abuse and violence against children and adolescents.”

This chapter first defines terms relevant to the problem of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States. It then presents a set of guiding principles that should inform any efforts to address the problem. Next is a brief discussion of what is known about the extent of the problem. The final section summarizes the current understanding of risk factors and consequences. One of the messages that emerges from this discussion is that, while the gravity of the problem is clear, critical gaps in the knowledge base for understanding and addressing it need to be filled.

The language used to describe aspects of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking crimes and their victims and survivors—a collection of terms derived from the range of agencies, sectors, and individuals working to prevent and address these crimes—varies considerably. Some terms are diagnostic and scientific (e.g., screening and medical forensic exam). Others are legal terms (e.g., trafficking, offender, perpetrator). Some terms are used frequently in popular culture (e.g., pimp, john, child prostitute). Still others are focused on the experiences of exploited children (e.g., victim, survivor,

modern-day slavery). The result is the absence of a shared language regarding commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

The implications of this absence of a common language can be significant. For example, a child or adolescent victim identified as a prostitute may be treated as a criminal and detained, whereas the same youth identified as a victim of commercial sexual exploitation will be referred for a range of health and protective services. Box 1 provides the definition used in the IOM/NRC report for the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. Box 2 presents the report’s definitions for some of the more common terms related to these crimes.

Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors are distinct but overlapping terms. Indeed, disentangling commercial sexual exploitation from sex trafficking is impossible in many instances. Two points are particularly important for readers of this guide. First, programs designed for victims and survivors will need to account for a range of experiences and needs among those being served. Second, as reflected in the guiding principles presented in the next section, it is crucial to recognize and understand commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors as part of a broader pattern of child abuse (as illustrated by Figure 1).

BOX 1

Definition of Commercial Sexual Exploitation

and Sex Trafficking of Minors

Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors encompass a range of crimes of a sexual nature committed against children and adolescents, including

• recruiting, enticing, harboring, transporting, providing, obtaining, and/or maintaining (acts that constitute trafficking) a minor for the purpose of sexual exploitation;

• exploiting a minor through prostitution;

• exploiting a minor through survival sex (exchanging sex/sexual acts for money or something of value, such as shelter, food, or drugs);

• using a minor in pornography;

• exploiting a minor through sex tourism, mail order bride trade, and early marriage; and

• exploiting a minor by having her/him perform in sexual venues (e.g., peep shows or strip clubs).

BOX 2

Definitions of Other Key Terms

Minors—Refers to individuals under age 18.

Prostituted child—Used instead of child prostitute, juvenile prostitute, and adolescent prostitute, which suggest that prostituted children are willing participants in an illegal activity. As stated in the guiding principles in the text below, these young people should be recognized as victims, not criminals.

Traffickers, exploiters, and pimps—used to describe individuals who exploit children sexually for financial or other gain. In today’s slang, pimp is often used to describe something as positive or glamorous. Therefore, the IOM/NRC report instead uses the terms trafficker and exploiter to describe individuals who sell children and adolescents for sex. It is also important to note that traffickers and exploiters come in many forms; they may be family members, intimate partners, or friends, as well as strangers.

Victims and survivors—Refers to minors who are commercially sexually exploited or trafficked for sexual purposes. The terms are not mutually exclusive, but can be applied to the same individual at different points along a continuum. The term victim indicates that a crime has occurred and that assistance is needed. Being able to identify an individual as a victim, even temporarily, can help activate responses—including direct services and legal protections—for an individual. The term survivor is also used because it can have therapeutic value, and the label victim may be counterproductive at times.

“Minors who are commercially sexually exploited or trafficked for sexual purposes should not be considered criminals.”

The IOM/NRC report offers the following guiding principles as an essential foundation for understanding and responding to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors:

• Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors should be understood as acts of abuse and violence against children and adolescents.

• Minors who are commercially sexually exploited or trafficked for sexual purposes should not be considered criminals.

• Identification of victims and survivors and any intervention, above all, should do no further harm to any child or adolescent.

FIGURE 1 Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors are forms of child abuse.

NOTE: This diagram is for illustrative purposes only; it does not indicate or imply percentages.

“Despite the current imperfect estimates, commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States clearly are problems of grave concern.”

Despite the gravity of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States, these crimes currently are not well understood or adequately addressed. Many factors contribute to this lack of understanding. For example:

• Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States may be overlooked and underreported because they frequently occur at the margins of society and behind closed doors. Their victims are often vulnerable to exploitation. They include children who are, or have been, neglected or abused; those in foster care or juvenile detention; and those who are homeless, runaways (i.e., children who leave home without permission), or so-called thrown-aways (i.e., children and adolescents who are asked or told to leave

home). Thus, children and adolescents affected by commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking can be difficult to reach.

• The absence of specific policies and protocols related to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, coupled with a lack of specialized training, makes it difficult to identify—and thus count—victims and survivors of these crimes.

• Victims and survivors may be distrustful of law enforcement, may not view themselves as “victims,” or may be too traumatized to report or disclose the crimes committed against them.

• Most states continue to arrest commercially exploited children and adolescents as criminals instead of treating them as victims, and health care providers and educators have not widely adopted screening for commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. A lack of awareness among those who routinely interact with victims and survivors ensures that these crimes are not identified and properly addressed.

As a result of these factors, the true scope of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors within the United States is difficult to quantify, and estimates of the incidence and prevalence of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States are scarce. Further, there is little to no consensus on the value of existing estimates. This lack of consensus is not unusual and indeed is the case for estimates of other crimes as well (e.g., rape and intimate partner violence).

The IOM/NRC report maintains that, despite the current imperfect estimates, commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States clearly are problems of grave concern. Therefore, the report’s recommendations go beyond refining national estimates of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States to emphasize that unless additional resources become available existing resources should be focused on what can be done to assist the victims of these crimes.

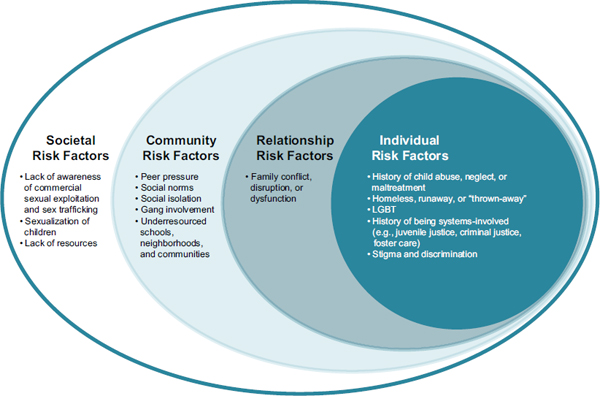

Risk factors for victims of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors have been identified at the individual, family, peer, neighborhood, and societal levels (see Figure 2).1 Adding to this complexity, these risk factors, as well as corresponding protective factors, interact within and across levels.

1It should be noted that the evidence base for risk factors, as well as for consequences (discussed in this section) is very limited. Therefore, the IOM/NRC report draws heavily on related literature (such as child maltreatment, sexual assault/rape, and trauma), as well as evidence gathered through workshops and site visits.

FIGURE 2 Possible risk factors for commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

NOTE: LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender.

Figure 2 highlights the complex and interconnected forces that contribute to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. It should be noted, however, that the factors shown are likely only a subset of the risk factors for these crimes. Moreover, these factors do not operate alone. For example, the presence of one or more risk factors would not result in the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors without the presence of an exploiter or trafficker. The factors depicted in Figure 2 may function independently of one another or in combination. In addition, risk factors in one sphere may trigger a cascade of effects or initiate pathways into or out of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking.

Finally, the factors in Figure 2 may also be risks for other types of adverse youth outcomes. Therefore, their presence does not necessarily signal commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, but should be considered as part of a more comprehensive assessment to determine youth at risk of or involved in these crimes.

Box 3 summarizes findings from the IOM/NRC report that highlight the risk factors depicted in Figure 2.

“Overall, research suggests that victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking face developmental, social, societal, and legal consequences that have both short- and long-term impacts on their health and well-being.”

The available literature shows that child maltreatment, particularly child sexual abuse, has significant negative impacts on the physical health, mental health, and social functioning of victims in adulthood, and leads to increased health risk behaviors and mental health problems among adolescents. While studies focused on consequences for commercially sexually exploited children and adolescents are rare, the data based on child sexual abuse are useful given evidence that these problems are linked in some cases. Overall, research suggests that victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking face developmental, social, societal, and legal consequences that have both short- and long-term impacts on their health and well-being.

BOX 3

Findings on Risk Factors

• Child maltreatment, particularly sexual abuse, is strongly associated with commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

• Psychogenic factors, such as poor self-esteem, chronic depression, and external locus of control, in addition to low future orientation, may be risk factors for involvement in these crimes. This possible link is supported by the association between child maltreatment and these psychogenic factors.

• Off-schedule developmental phenomena, such as early pubertal maturation, early sexual participation, and early work initiation, have negative consequences for youth.

• While commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking can affect youth across the board, some groups are at higher risk, including those who lack stable housing (because of being homeless, runaways, or “thrown aways”) and sexual and gender minority youth. In addition, some settings and situations—homelessness, foster care placement, and juvenile justice involvement—are particularly high risk under certain circumstances, providing opportunities for recruitment.

• Substance use/abuse is a risk factor for commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors and also may perpetuate exploitation.

• The sexualization of children, particularly girls, in U.S. society and the perception that involvement in sex after puberty is consensual, contribute to the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

• Disability should be considered a vulnerability for involvement in these crimes given its association with child sexual abuse.

• Online and digital technologies are part of a complex social system that includes both risk factors (recruiting, grooming, and advertising victims) and protective factors (identifying, monitoring, and combating exploiters) for these crimes.

• Beyond child maltreatment, the experience of childhood adversity, such as growing up in a home with a family member with mental illness or substance abuse or having an incarcerated parent, may increase the risk for involvement in commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

• Peer pressure and modeling can influence a youth’s entry into (or avoidance of) commercial sexual exploitation.

• The neighborhood context—such as community norms about sexual behavior and what constitutes consent and coercion, and whether the community is characterized by poverty, crime, police corruption, adult prostitution, and high numbers of transient males—can increase the risk for involvement in these crimes.