5

Strategies for Financial Sustainability

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

—Proverb

Many field stations need a substantive transformation of their business practices and a long-term vision and strategy if they are to be financially sustainable. A report of the National Association of Marine Laboratories (NAML) and the Organization of Biological Field Stations (OBFS) and the details the future directions for science at field stations and provides some guidance to ensure that field stations are well positioned to advance research and innovation, education and training, and outreach in the 21st century (Billick et al. 2013). The NAML-OBFS report recommends that field stations increase their operational effectiveness, but it does not outline strategies on how to do it. In this chapter, the committee outlines how field stations should combine visionary leadership with strategic science and business planning to ensure long-term viability.

The goal of a comprehensive planning effort is to identify and articulate a compelling strategic vision and mission, to identify the assets of a given field station (or network of stations), to identify the future research challenges that it is uniquely positioned to address, to identify its unique education and outreach goals, metrics for measuring progress toward its goals, and to identify its value proposition (see Box 5-1). A programmatic planning effort should be supplemented with a business plan that makes explicit the field station’s value proposition and that includes strategies that contribute to its financial sustainability.

In developing a business plan, a field station should start by identifying its assets, including the products and services that it provides. In the aggregate, these become key elements of the field station’s value proposition and can lead to

BOX 5-1

Definition of Value Proposition

“[In marketing,] an innovation, service, or feature intended to make a company or product attractive to customers.” (Oxford Dictionary)

A field station’s value proposition can include elements as varied as longitudinal datasets, housing and conference facilities, extension and outreach learning opportunities for local communities, stewardardship of local natural history, and provision of rich research experiences at the convergence of disparate scientific disciplines. A field station’s value proposition will be of interest to an array of stakeholders, including scientists, funding agencies, alumni, local or nearby business owners and communities, citizen scientists, and possibly major corporations.

revenue that adds to the core support providing a hedge against fluctuations in any one source of support. Potential assets that can be monetized include educational programs, room and board, personnel (such as technicians), access to laboratory equipment, biological collections, and even access to data that have been collected at a site and that provide the context for a visiting investigator’s work. Each field station may have a different set of assets given its location, size and array of facilities, available long-term datasets, research equipment. personnel, and other resources. Assets that reflect the unique qualities of field stations, such as their physical location and access to distinctive ecosystems and their capability to merge science, education, and outreach unlike other institutions are particularly important for developing their value proposition. Executing the process identifying and assigning value to assets not only will allow a field station to inventory and document its assets, but will provide the information to market the assets to generate diverse sources of funding in support of its facilities and programs. However, careful consideration should be given to whether assets should be monetized for logistical, historical, or other strategic reasons. Successful expansion of public–private partnerships depends on a stable core of support that can be leveraged through a diversified value proposition that attracts an array of funding streams. It also depends on the visionary entrepreneurship of field station leaders who can attract and inspire funders and other partners.

Effective leadership is one of the most critical factors in financial sustainability of field stations (Lohr 2001, NRC 2005). If field stations are to survive in the 21st century, they need leaders who will make them indispensable to their parent institutions. The idea of a field station as a separate and independent unit, often so remote as to be forgotten, is a thing of the past. The increasing sophistication of science, challenging economic realities, and the demand for greater accountability conspire to increase the demands and expectations of field station leadership. It behooves parent institutions and trustees to choose directors wisely and to place appropriate emphasis on the skill set a director will need to succeed.

There are parallels between the management needs of field stations and the management needs of businesses. One could say that field stations are in the “business” of scientific research, conservation, education, and public outreach. As such, the management of a field station requires individuals not only with scientific credentials, but also skills and experience in running successful businesses.

Often, the most common criterion in selecting the director of a field station, particularly one affiliated with a university, is the person’s stature as a scholar who will command the respect of participating faculty. Equally important, however, is that the director have strong leadership and management skills and is able to gain the respect of employees, students, potential funders, and members of the public. The leader needs to be willing to put the success of the organization that he or she leads ahead of—or at least on a par with—his or her own success as a scholar. The metrics for assessing the director’s performance should be clear and explicit before

hiring. For example, if a leader is hired as a tenured or tenure-track faculty member at a university-supported field station, it is important that tenure criteria and performance metrics reflect the roles and mission of the field station, which may differ in part from the roles and responsibilities of on-campus faculty. Many of the skills needed for success in leading a field station are not part of the skill set of the typical academic scholar, and they may need to be enhanced or provided by another member of the field station’s leadership/management team.

Field station directors are responsible both for building and sustaining the infrastructure that allows emerging science to thrive and for cultivating durable relationships with the parent organizations, the primary source of core support for most field stations. This requires that directors spend a significant amount of time working with key decision makers to develop a shared vision and trust while emphasizing the station’s critical contributions to the parent institution’s high-priority initiatives. This takes on particular importance for a field station affiliated with a university if it is to receive the same financial benefits and services as on-campus units. It also requires inviting university leaders and administrators to the field station, which is more easily accomplished once the relationship has developed.

Field station leadership may be implemented by using a variety of models. Depending on the size of the facility, various support staff may also be required to run and maintain it. In some cases, the dual roles—leader and manager of the field station—are held by one person, but in many cases the two roles are separated. The leader, or “champion,” is likely to be a tenured academic who has a reputation as a researcher in a field relevant to the field station. The academic leader’s salary often is a permanent line in a university budget. An operations manager, in contrast, is likely to be a person whose entire salary comes from the field station budget and may need more frequent justification to be established or maintained over the long term. A group of faculty that is committed to the success of the field station can often provide the energy and enthusiasm to sustain and support the leadership team and field station staff. Such a group can be vital in securing funds for research and for new infrastructure, in using the field station for classes, and in assisting in decision making and in securing institutional support. Finally, it is essential to plan for leadership succession. A change in a field station’s director should not cause the business or programmatic underpinnings of a field station to falter. If a field station lacks adequate leadership, its long-term sustainability will be compromised.

Various models are available for leading and managing field stations. Data from the NAML-OBFS survey of field stations (227 responses from 444 potential field stations) indicate that 72% have station directors, 62% have maintenance staff, 51% have office staff, and 49% have research technicians (NAML-OBSF 2013b). Those were the most commonly reported staff positions. Much smaller percentages of the facilities have information technology staff (21%), research directors (21%), data managers (21%), or education staff (27%). These data are insufficient for developing the best performance model, which varies with the size, complexity, and management scheme, but they identify the models that are used

most often.

Many directors will need training if they are to accomplish the leadership goals expected of them. Training is also critical for developing the next generation of effective science administrators. Training can be in the form of workshops that focus on creating vision and mission statements and business plans to support them, and that highlight successful leadership models that can be scaled to meet the needs of different kinds and sizes of field stations. Field stations associated with universities can work with their on-campus business schools in developing business plans. Those without business schools can turn to such organizations as the Senior Executive Service Corps that provide expert assistance to nonprofits at little or no cost to their clients. Workshops could be supported by NAML, OBFS, the National Science Foundation (NSF), or by other organizations. We applaud the recently launched Ecological Society of America Sustaining Biological Infrastructures initiative, funded by NSF.36 Its first activity will be a workshop to train project directors in strategies for success. It is important to point out, however, that project management and program leadership and management are different challenges.

Success in a Time of Declining Resources

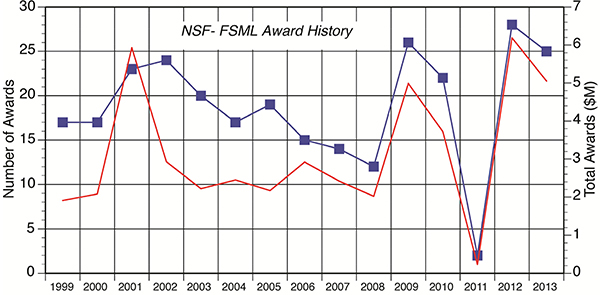

Funding from federal government grants and from most parent organizations, particularly universities, to support daily operations of field stations will continue to be a serious challenge for at least the near future. The bulk of support for most field stations generally comes from field stations’ host institutions, but field stations have come to depend upon other sources to push their research and education agendas forward. Among them is the NSF program Improvements in Facilities, Communications, and Equipment at Biological Field Stations and Marine Laboratories. The program has provided more than $47 million in support over the last 15 years, specifically for the infrastructure needs of individual field stations at accredited U.S. universities and nonacademic organizations and should be continued (Figure 5-1 37). But the present financial situation of many field stations may not be sustainable. The committee believes that many field stations need to stabilize their base funding and diversify their funding portfolios.

If they are to be sustainable, many field stations need to make a more compelling case for their importance from the perspective not only of science and education, but also from other contributions they make to society if they are to be sustainable. Field stations can be important parts of local culture. They often maintain the best records of how the natural environment of a region has changed, and they may employ generations of local youth as field assistants or station workers. Evidence of a cognitive and physical health benefit from experiences in

__________________

37Information on the NSF awards was obtained from its public awards database, http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/.

FIGURE 5-1. NSF field station and marine laboratory award history (1999-2013).The red line indicates the number of awards; the blue line indicates the total award amounts. The dip in 2011 reflects a change in the proposal deadline from early in the year to December. Data for this chart was obtained from the NSF public award database: http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/.

nature is growing (Bratman et al. 2012). In some nations, forests are being established as a form of medicine.38 Field stations have a role to play in this growing sense of the major health benefits of interaction with nature. Field stations are also employers. For example, aquariums and marine laboratories in the Monterey Bay Crescent combined have 1,726 employees whose wages total more than $77.7 million (Miller 2007). Thus, thinking of the value of field stations simply in terms of scientific publications or even number of students taught yields too narrow a perspective. Field stations should make as broad a case as possible for the public good that they deliver.

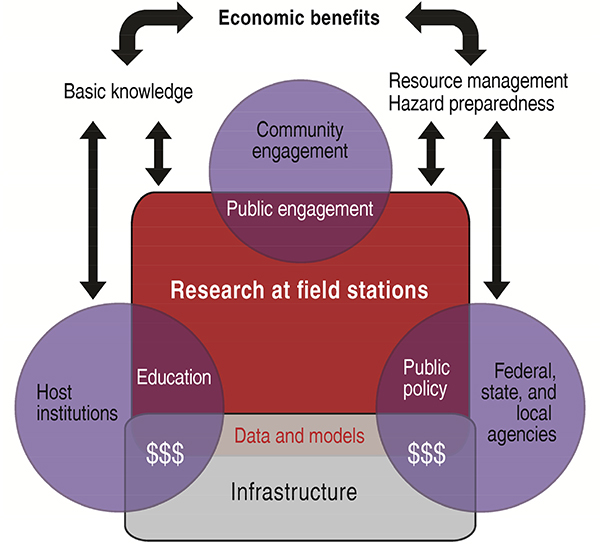

A November 2013 report released by Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell showed that national wildlife refuges contributed $2.4 billion to the U.S. economy and supported more than 35,000 jobs in 2013 (Carver and Caudill 2013). Field stations—particularly networks of field stations—would benefit from evaluating and sharing the links among their infrastructure and activities, stakeholder communities, and economic benefits (see Figure 5-2). Because a field station’s infrastructure underlies all of its program and activities, a field station’s value proposition, funding portfolio, and potential economic impacts are anchored in maintaining and upgrading its infrastructure. Economic impact analyses do not necessarily need to be conducted at each field station, but rather could be a coordinated effort of networks of field stations, to which economic multipliers can be applied for similar types of operations.

__________________

Field stations also generate indirect economic benefits, such as providing expertise and data for use by industry (such as commercial and recreational fishing, aquaculture, and renewable energy) and helping to create the next-generation workforce of scientists and technicians.

Before a station’s leaders develop strategies for long-term, sustainable support, they need to be able to answer a basic question: What is the return on investment?

Return on investment is a performance measure that is used to evaluate the efficacy of an investment. Field stations should be cognizant of the needs of their primary funding source (usually a university), local communities, and society at large and should actively and regularly seek their input. Knowing and understanding the community and societal needs can help field stations construct better and more effective research, education, and public-outreach programs and fundraising efforts. Appropriate metrics of the programs enable field stations to measure and articulate the returns on investment to current and future funders.

A stable, predictable, and adequate level of base support is a prerequisite for planning and is central to securing support from other sources to diversify a field station’s funding portfolio. Stabilizing base funding support of field stations is essential, particularly for those affiliated with academic institutions. Universities and other funders not only should commit to a sustained level of base support for their field stations, but also need to provide professional financial and fundraising assistance to field station leaders, many of whom have had little experience in financial management and fundraising.

Continuity of support for field station infrastructure—including information technology, base maintenance and operations, and long-term operations—is essential for addressing our nation’s environmental challenges in light of ever-increasing human pressures. Field stations should work together more effectively to share relevant data and other resources in a timely way. As discussed in Chapter 3, networking can make such efforts more efficient and effective.

Importance of a Diversified Funding Portfolio

One of the key factors in ensuring the stability and sustainability of field stations will be the development of diversified portfolios of funding sources that will be more resilient in challenging economic times. Diversity of funding sources reduces an institution’s vulnerability to fluctuations in any one source of funding. Many field stations, particularly those affiliated with universities, depend too heavily on a single funding source for their support. As pointed out above, it is important that parent institutions provide a stable core of base support for their field

stations, but they should expect that this support will be leveraged. Most field stations have many opportunities to diversify and supplement their sources of funding.

The first step in creating a diversified funding base is the development of a solid business plan. Many potential funders will insist on this before they will consider making an award. A business plan should also help in securing and stabilizing core support from a host university. The importance of this approach became clear to members of the committee in discussions with the former directors of the Wrigley Institute of the University of Southern California, the Hopkins Marine Station, the Mote Marine Laboratory, and the Duke University Marine Lab and with the present director of the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project.

FIGURE 5-2. Links between field stations, stakeholder communities, and economic benefits. A field station’s infrastructure underlies all of its programs. Infrastructure provides the basis for development of projects and activities in science, education, and public engagement along with connections to partners and stakeholders that share in these activities and related economic outcomes. Investments in constructing, maintaining, and upgrading a field station’s infrastructure (buildings, equipment, biological collections, datasets, etc.) are linked to eventual economic benefits of field station activities.

Partnerships with private enterprises depend on financial motivations, such as research and development opportunities that have tangible profit outcomes or marketing relationships that may enhance a company’s reputation or its products. Such opportunities may arise from time to time and should be seized when they occur and when they are appropriate, but they should not be counted on to make a large difference in the financial viability of field stations in general.

A networked community of collaborative field stations that shares resources, including human resources, will be more resilient than individual field stations in the face of stresses and shocks. A networked community will also be more capable of using technological advances to meet changing needs and to exploit new opportunities of science and society. The challenges and benefits of networking are explored in Chapter 3. Each field station will need to consider how to facilitate collaborations with other field stations and research organizations (e.g., for cost- and revenue-sharing reasons) that may operate with different funding models.

The value of field stations to society, local communities, and the nation warrants reliable institutional support. Aging infrastructure, the need for advanced technology and cyberinfrastructure, and evolving safety regulations are increasing financial demands on field stations as they upgrade to meet emerging science and societal challenges. Sustainable funding for modern infrastructure will be possible only if field station leaders develop compelling value propositions, strategic plans, and business models for operations that can secure base funding support which in turn can be leveraged by support from diverse sources. However, field stations leaders too often lack the required entrepreneurial skills. Effective business planning requires strong linkages to funding institutions and reaching out to diverse constituencies that can derive value from field stations.

Recommendation: Field stations and their host institutions should develop business plans that include clear value propositions and mechanisms to establish reliable base funding commitments that can be supplemented with funding from diverse sources. Business planning requires that station leaders be recruited not only for their scientific credentials but also for their leadership, management, and entrepreneurial skills. Host institutions should provide mentoring of field station leaders in management, business planning, and fundraising when appropriate.