4

Engaging Forestland Owners: Perspectives from the Social Sciences

Social and behavioral scientists have identified ways to communicate effectively about complex ideas and to change the way people behave, and have explored the many factors that influence behavior change. Four social and behavioral scientists discussed insights from that body of research and the implications for communication about climate change. A panel of social scientists and foresters drew on their experiences working with forestland owners in offering their responses to the presentations.

IDENTIFYING EFFECTIVE MESSAGES

Purnima Chawla, executive director of the Center for Nonprofit Strategies, linked ideas raised by the case studies discussed in Chapter 3 to concepts from the fields of social marketing, organizational behavior, and human decision making. She organized her observations around four elements that make communication effective. First, a lot of research documents the importance of the actual communication behavior, and which features make it easier or more difficult for people to understand one another. The content—the reason for communicating something in particular—is also important, she noted. So, too, is the context of the message: Its source, the place in which it was delivered, and “the contextual or emotional cues in the environment or in the communication materials all set the frame for the messaging,” she explained. Last is the way people remember the message.

She elaborated on the relevance of just one of these—the content—in the context of communication with forestland owners. There are four basic types of content, or reasons why people want to use communication to induce others to do something, she explained. One is to convey a strategy for solving a problem. Another is to identify a valued outcome the listener can obtain. These two are easy messages to convey, she explained, and often fit naturally with the circumstances facing forestland owners—such as fire risk or the possibility of increasing the benefits of timbering or recreational use of forestland. The problem with both is that listeners have many issues to pay attention to, so uncertainty about the timeframe or urgency of the problem or benefit may undercut the message.

Uncertainty about the urgency and timeframe is an obvious problem with messages about climate change, Chawla explained. What may or may not happen in a particular place, when and how it may happen, and the likelihood that a particular action will make a difference, are all uncertain. Similarly, it may be that one day in the future carbon credits will yield profits, but when and how much is not known. The risk of wildfire, she noted, is more immediate than the risks of climate change. It is also true that landowners are often likely to be motivated to take immediate steps to protect their land from fire, whereas, for many, the fear of climate change may be overwhelming if they feel there is little they can do about it.

The two other types of messages may be more effective when it comes to climate change, she explained. Connecting behaviors to a value people hold is one effective way to communicate a message; a value that many forestland owners identify with is stewardship, Chawla observed. “People spend a lot of energy doing things that have no immediate positive outcome for them,” she explained. “One motivation for doing so is to reinforce their impression of who they are and who they would like to be.” The difficulty with this message, however, is that values and behaviors should be understood as a network, and a particular set of values may point to several different behaviors. Thus, the challenge for the communicator is to connect the recommended behavior to the value most likely to be a motivating influence.

In other words, she explained, “people may say ‘yes I am a good steward, but I don’t see this behavior as an expression of my stewardship ethic.’” In such cases, she added, repetition of the rationale can be very effective. For example, she observed that the connection between building a legacy and estate planning with stewardship of the forest itself may not be apparent immediately because “it is not a natural connection people make.” But if the message is repeated, the target audience has more opportunities to consider it and recognize that stewardship can mean taking a longer perspective and planning for what will happen to land

after it changes hands. “Usually attitudes and values are very broad,” she added, so “you really have to spell it out and be convincing.”

The fourth message strategy, Chawla explained, is social. Here the message is not that the landowner will take an action because of his or her sense of values and goals, but rather because of a desire to belong to the tribe of people who behave a certain way. The message might build on the idea that “people like me are doing this,” or on beliefs about what others will think of particular behaviors. The logic of this sort of message suggests focusing more on positive things than negative ones, Chawla explained, citing an example from another field. Researchers have found that a message about how much damage tax evasion does to society was less effective than one that highlighted the fact that the majority of people actually do pay their taxes. The idea, she explained, is to “establish the norm.”

There is no one right message strategy for any situation, Chawla observed, and “each has its pitfalls.” Crafting an effective message, therefore, requires segmentation. “Not everybody is going to do things for the same reason, but you can confuse people enormously if you give eight reasons to do something instead of one,” she added. Thus, it is necessary to address one target at a time, based on a clear understanding of what that group values.

Chawla closed with the observation that the relationship between attitudes and behavior is neither linear nor one-directional. “Sometimes,” she explained, “if you can get people to do something, that actually strengthens their identity.” At the same time, asking repeatedly that people take a particular action is more effective than asking them to do multiple things and hoping they will do one of them. Similarly, she concluded, a person who has agreed to one small thing is likely to be more receptive to a follow-up request to take a more significant action.

THE ROLE OF COMMUNITY

Maureen McDonough, professor of forest sociology and social forestry at Michigan State University, offered perspectives from the field of natural resources sociology about social relationships within communities, as they pertain to forestland owners. She began with approaches she observed in the case studies that align well with the research literature she tracks. First, she noted, sociologists consider that human beings exist as members of networks and communities, and so she was pleased to see excellent examples of network-building in the case examples. For example, identifying representative community members who can reach out to their neighbors and building communities of volunteers fit well with the sociological approach.

Trust is very important to communities and is the basis for people’s willingness to engage in a new behavior, McDonough added. Researchers have found that just as trust is a key variable, so, too, lack of trust can be a significant obstacle. Thus, she noted, it is important to try to understand how much trust target audiences have in the messengers who are responsible for reaching them, whether they are neighbors, professionals, or government officials.

On the other hand, she noted that social science could be useful in ways she did not see reflected in the case examples. Most important would be to better understand the complex social contexts in which people make decisions. She noted that she and her husband used two cars to drive an identical commuting route for many years, even though they were committed conservationists, because other factors—such as the decision to drive children to sporting events—affected their lives. “People say they will do things,” she commented, and “they may want to do them,” but it is important to understand the obstacles that arise in their personal communities. “It can be futile to try and change people’s values,” she added in answer to a question. Values have multiple sources and they are different across generations. Younger generations, she added, are more receptive to messages about climate change than their elders—they may have similar values but express them differently. Trying to convince people that “you are right and they are not is not going to be effective,” McDonough observed.

Political science research also offers insights about how people expect to participate in decision making, she added, and she did not hear much discussion in the case examples about including landowners in decision making. Research, she noted, suggests that “if you want people to behave in a certain way, you need to empower them.” It is best to involve people early in the process, she added, using a collaborative, consensus-building process. “This requires some behavior change on the part of natural resource professionals,” she added. She heard a lot of discussion about how to share information that people need, but little about the knowledge they already have and how that can be tapped into and built on.

The information context is also important to consider, McDonough observed. Sources of information have multiplied exponentially in the past few decades, and those who want to reach forestland owners must “navigate that.” It is much more difficult to get people’s attention than it used to be. More broadly, it is also important to consider cultural influences. A few of the case study presenters talked about people’s reasons for owning their land, she noted, and referred to “logical” reasons for acting in certain ways. Scientists do not necessarily define logic in the same way other people do, she noted. Research has explored how people think about what they believe, she observed, and suggests that “belief systems

are very powerful, and they are not generally based on facts.” To engage effectively with landowners, she concluded, will require moving beyond logic and consider that “most people make decisions based on their hearts and their guts…and scientists make decisions based on their heads.”

PRINCIPLES OF COMMUNICATION

Many of the practices described in the case examples correspond to theoretical models from the social sciences, Joe Heimlich, professor and extension specialist at Ohio State University, observed, but he said that a fuller understanding of those theories and how they function would make it possible to improve engagement with forestland owners. He focused on communication, noting that it may seem simple: “coming up with an idea, encoding that idea, and transmitting it through some kind of medium toward a target.” People tend to expect that others receive their messages in the way they are intended to come across, he explained, but in reality communications are interpreted through filters that may significantly complicate the transmission. The basic question—of what goes wrong and keeps people from receiving messages as they were intended—underlies much of the research in educational and learning psychology, as well as communications, he added.

There are many distinct factors that distort communications, Heimlich noted, that have generated lines of research. Noise, or distortions that affect the encoding and decoding of the message, is one (Goldstein, 2014). Another is perception (Berliner, 1955), the process by which people use their senses to collect information and organize and filter it. “How we perceive things affects how they are framed in our minds,” Heimlich explained. Similarly, people have expectations that shape the way they perceive communications. “If I expect a conversation is going to be hard, it will be hard,” he noted, but “if I expect a person will give me good information, I will receive it.”

Information load is another potential obstacle (Lavie et al., 2004). There are many influences and stimuli in people’s lives, Heimlich explained, that may get in the way of their capacity to hear or receive a given communication. He noted that gambling casinos take advantage of this phenomenon by making their environments so loaded with sensory input that visitors’ senses are numbed, and “because of that, many people do exactly what they [casino operators] want us to do when we are in those places.” Limits on people’s skill at listening are yet another potential obstacle to communication, Heimlich added. It is “an art that we tend not to practice very much—we hear but we don’t listen, we don’t really get the nuance.” Context is key to listening with understanding,

he added, noting this as one reason why the tone of e-mail messages is often puzzling.

These insights can be used for good or evil, Heimlich observed. To use them in engaging constructively with forestland owners, it will be helpful to get the right stimulus to the target audience in such a way that the audience responds in the desired way. A starting point is to explore landowners’ habits and behaviors. Much of what people do on a daily basis is embedded in routine, he noted. For example, most of the actions a person takes when getting into the car and driving to work are routine, but if one took time to think about each activity associated with driving to work “it could take 10 or 15 minutes to get out of the driveway.” This is important, he explained, because it means that to get a person to change the way he or she behaves, it is necessary to look at a whole pattern of routine behavior.

Thus, Heimlich went on, “telling people to do something is not teaching them a behavior,” while to teach the behavior is to help the individual understand “how to practice, apply, and perfect the skill in the context of his or her routines.” This would mean “starting with the behavior you want them to take, working backwards to see where would you embed that in their practice,” and then determining how the new behavior might fit the existing routine. He acknowledged, in response to a question, that behavioral theories identify different points as the optimal levers for getting a person to change a behavior.

Heimlich noted that it is important to recognize, as many of the presenters had done, that people have a range of reasons and motivations for the things they do, and that they themselves may not always recognize all of the factors that influence their actions. They also may not receive or respond to messages that are not present when they are needed. That is, those working with landowners may believe they have done all they can if they “put things in newspapers, sent e-mail blasts and broadcasts, talked with everybody” but people still say they had not heard about the message. The reason, Heimlich explained, is that the messages were “part of the noise that they were not paying attention to.”

Sociocultural theory,1 Heimlich said, demonstrates the importance of culture in communication. Social role is a significant determinant of people’s actions, and it is a dynamic, rather than a static, concept. For example, a message to forestland owners about the land as a family legacy may come across differently depending on whether the recipient is hearing it as “the child of his grandparents or as the parent of his children and grandchildren.”

__________________

1Sociocultural theory is a psychological theory that stresses the importance of cultural contribution to an individual’s cognitive and social development.

What all of these insights point to, in Heimlich’s view, is that “we can’t change people, we can change how we frame things.” Specifically, he concluded, this would mean that those who want owners to take an action or change a behavior need to try to understand how that change would relate to existing routines, the context for the shift. Other questions to consider include: What is the potential return on investment for the owner who might make a change? Does the landowner have the power and the resources to make the change? Would the outcome clearly be at least equivalent in benefit to the current approach? What are the tradeoffs? Are there intangible benefits that can be made clearer?

COMMUNICATION ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE

Many social scientists have focused specifically on communication about climate change. Christopher Clark, assistant professor in the Department of Communication at George Mason University, described some of that work and how it might relate to engagement with forestland owners. Public opinion about climate change is surveyed twice a year in the United States2 and the survey data have helped him and his colleagues consider strategies with respect to three goals for engaging people on the topic. One is to engage people on a cognitive level—so that they will understand the scientific consensus that climate change is taking place. People have emotional reactions to that knowledge, Clark added, so it is also important to engage them on an affective level, whether their reaction is one of optimism, fear, worry, or something else. The third goal is to persuade people to change their behavior, both personally—such as driving more fuel-efficient cars—and at a macro level, by supporting policy changes, for example.

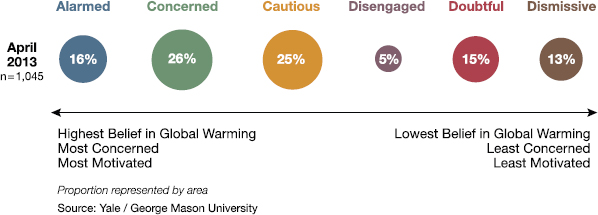

“I’ve never come across an issue that’s as politically polarizing, ideologically, left/right, red/blue, democratic/republican, as climate change,” Clark observed. Several lines of research hold promise for meeting the three engagement goals even in this polarized context, however. As many others at the workshop had noted, the basic strategy is to understand the audience, design messages based on that, and use trusted sources to deliver it. Building on that, he explained, begins with the profile of six distinct groups of Americans’ understanding of climate change, shown in Figure 4-1 (also discussed by Geoffrey Feinberg as the “Six Americas”; see Chapter 2).

Clark and his colleagues have tracked changes in the opinions of these groups over time. The most recent data show stark differences in

__________________

2See http://environment.yale.edu/climate-communication/article/extreme-weather-public-opinion-September-2012 [February 2014].

FIGURE 4-1 Global warming’s “Six Americas.”

SOURCE: Leiserowitz et al. (2012b).

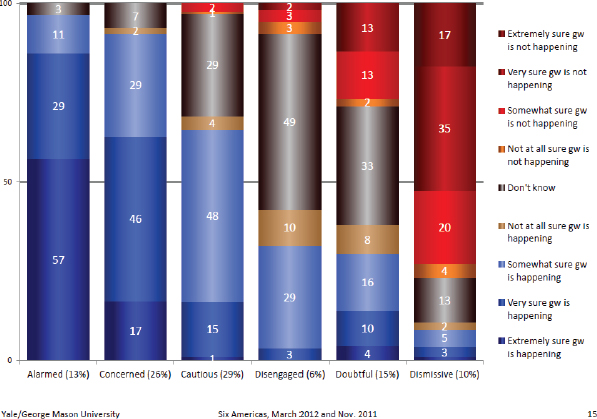

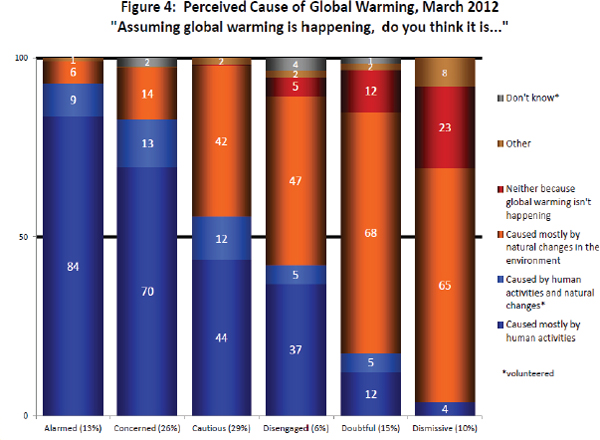

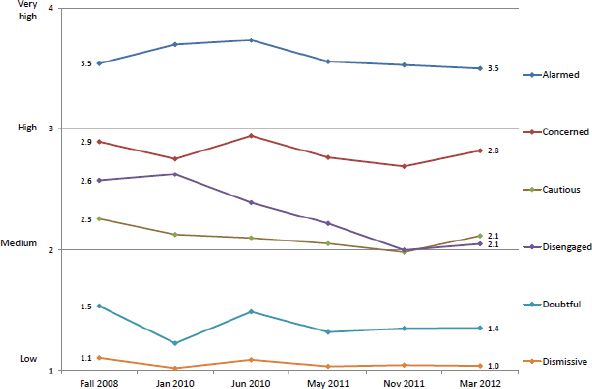

thinking among the groups, as Figures 4-2 and 4-3 show, and also differences in how important these groups believe the issue is (Figure 4-4). These results clearly show polarization, Clark noted.

Clark and his colleagues have also tested messages with the six identified subsegments of the U.S. population. This research suggests that

FIGURE 4-2 Certainty of belief about the reality of global warming, March 2012.

SOURCE: Leiserowitz et al. (2012b).

SOURCE: Leiserowitz et al. (2012b).

FIGURE 4-4 Priority of global warming for the President and Congress, 2008-2012.

SOURCE: Leiserowitz et al. (2012b).

perceiving that a consensus exists among scientists that global warming is happening is “a gateway belief that can drive other beliefs” about how likely it is that climate change could harm an individual or community, or the merits of proposed policies. Clark noted that the Consensus Project is one group that has focused on spreading understanding that 97 percent of climate scientists agree that climate change is caused by human actions.3 However, Clark noted, the six groups vary significantly in their responses to a simple visual image making that point.

He and his colleagues have also found variation in people’s responses to different ways of framing the concept of climate change. If people are asked how worried they are about it, half to two-thirds say they are worried, he explained. However, the majority do not see it as an urgent threat: 35 percent believe global warming will cause a moderate amount or a great deal of harm to them personally, while 63 percent believe it will cause harm to future generations or plants and animals. In other words, the further removed the threat seems to be “from me and mine,” Clark explained, the less concerned people are about it. He added, in answer to a question, that people’s responses to personal experiences with events that could be evidence that climate change is happening, such as extreme weather or drought, vary across the Six Americas. “If I’m in that dismissive group,” he noted, it may be that “no amount of odd weather could change that.” For those in the middle, however, extreme weather may be a “teachable moment,” he added. However, because the extremity of weather is relative, it is not possible to know how strong a storm would have been were climate change not happening, or how long and severe a particular drought would have been without climate change.4

Climate change as an issue can be framed in a variety of ways, and although it may seem “cavalier,” he commented, to develop “interpretive packages” that emphasize particular facets of the issue, he suggested this may be the most effective way to persuade people to accept that action is needed. For example, some evidence suggests that discussion of risks to public health posed by climate change, and the actions that might mitigate those risks, may be more compelling to audiences who have resisted other approaches to the topic. Thus, discussion of heat waves, extreme weather, infectious diseases, or improving air quality may be effective. Discussion of economic damage that will come with the effects of climate change, such as the losses associated with Hurricane Sandy, is another approach that has been effective. Still, Clark acknowledged, the “doubtful” and

__________________

3See http://theconsensusproject.com/ [January 2014].

4For further discussions on the significance of the Six Americas audience segmentation on climate communication in general, see National Research Council (2011).

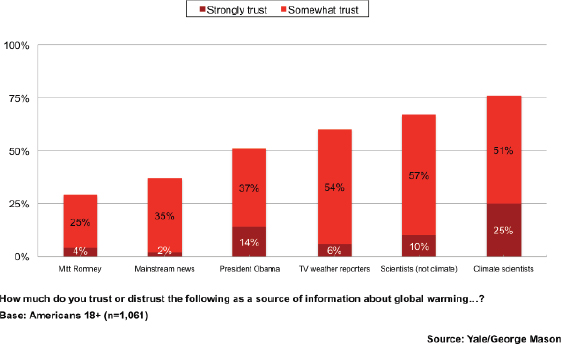

FIGURE 4-5 Public trust or distrust of sources of information on global warming, March 2012.

SOURCE: Leiserowitz et al. (2012).

“dismissive” groups are less responsive even to these messages than the other groups are.

Whatever the message, Clark went on, it will be most effective if it comes from a source the recipient trusts. Figure 4-5 shows data about how much trust people have in different sources of information about climate change. “People tend to trust climate scientists,” Clark pointed out, “but they don’t really know who they are.” Since people also trust weather reporters, Clark and others have begun to work with these reporters to encourage them to incorporate factual messages about climate change into their forecasts.5 This would mean not linking a particular weather event directly to climate change, he added, but elaborating on the context to help people experiencing a heat wave understand, for example, that heat waves are becoming more common because of larger patterns.

Climate change communication is a matter of “engaging hearts and minds,” Clark concluded, or cognitive, affective, and behavioral engagement. He believes the analysis of the Six Americas can be applied in any context in identifying messages that fit specific goals. A partici-

__________________

5Clark referred participants to a segment about the role weather reporters can play that was aired on National Public Radio in February 2013. See http://www.npr.org/2013/02/19/171832641/forecasting-climate-with-a-chance-of-backlash [January 2014].

pant observed in response that forestland owners already loosely group themselves by affiliating with various organizations, including the Forest Industry Trade Association, American Forest and Paper Association, state forestry agencies and extension programs, and American Tree Farm System, as well as land trust and community forest associations. These organizations may have very different objectives, which include protecting and promoting financial investment, sustainable stewardship, and other goals. Some focus on the interests of individual landowners while others look at “the whole enchilada: the air, the water, the wildlife habitat,” he commented.

PRACTITIONERS’ RESPONSES

Claire Layman, an extension public policy education specialist at Michigan State University (MSU), spoke about her experience working with the MSU state extension program. She was astounded when she began, she commented, to find that extension was largely not addressing climate change. She identified others within extension who were eager to share the information, and they began with field crop farmers. From talking with this group informally and in focus groups, she and her colleagues found that many believed they were being blamed for climate change, that they were not seen as stewards of the environment, and that they would be paying a regulatory cost. However, many also appreciated the opportunity to be heard, and Layman found that the conversations and information gathering were the start of a productive relationship.

Today, she and her colleagues are working with two communities in Michigan to create climate change adaptation plans. In one of the communities, she noted, a transportation planning organization advertised a public meeting to collect public input for their long-term planning effort that cited a desire to hear people’s thoughts about climate change. “This was like a siren call for the alarmed and the dismissive,” Layman explained. The planners wanted to avoid a scenario in which a scientist would make a presentation and then be “shot down” so they began the meeting by asking participants to suggest ways they thought the climate might be changing. Nevertheless, she added, the reactions were predictable and the “dismissive crowd was angry that we presupposed that the climate was changing.” For her, the lesson was that “even though extension is a trusted source, we came in from outside that community, we partnered with a source that many people saw as a bloated government entity, and we talked about climate change.” In retrospect, she believes that the approach they took with the farmers was more productive, and that if the topic of climate change is divisive, working around it may be wise.

Victor Harris, publisher and editor of Minority Landowner Magazine, offered the perspective of minority landowners. He and his colleagues, he explained, have the objective of providing valuable information about land management to their readers. They have learned, however, that it is important to begin by working to understand what the forestland owners’ objectives are, and provide guidance that helps with that, rather than with objectives of their own. He added that they try hard to convey that “every time you put in a crop, however many times a year, every year for how many years—whether it is corn or soybeans or tomatoes or trees—every time you touch that crop, you’re doing research. Your actions or inactions, that’s research.”

It is important to understand, he explained, that landowners understand a great deal about their land. Scientists have a language they are accustomed to using, he added, but in talking to forestland owners, “you have to translate that into something they understand.” Thus, for Harris, two points in the presentations were most striking. First, because the language used will determine how the message is received, it is vital to “deconstruct the message before sending.” Second, a critical point was that effective messages come from trusted sources.

James Houser, owner and consulting forester for James Houser Consulting Foresters, LLC, began by noting that as a professional forester who supports landowners in managing their property, he has noticed significant skepticism in his region (Texas) about politicians and the scientists who advise them. The majority of the landowners with whom he works do not live on their land and most use it primarily as an investment. They may have inherited it and are concerned about taxes and uncertainty—many are looking for information to help them in deciding whether to keep the land and develop timber growth or simply sell and take the profit. They want to know, Houser explained, “What’s my rate of return over the next years? Why shouldn’t I just clearcut it, take that cash now, let it grow back on its own, and do that about every 20 to 25 years?” A timber forest in Texas can be very profitable, Houser added, and most owners need to have a reasonable rate of return on investment to keep the property, even if they want to use it for recreational purposes as well.

Consulting foresters, who work only with non-industrial, private owners, view education as a key aspect of their mission. He and his colleagues need help, he explained. The forestland owners who are their clients “do not want to read scientific papers, they want to know the bottom line.” They are very concerned about the danger of fire, and Houser said he appreciates the link from that concern to climate change. They generally view their landownership as a business and are concerned about competing with larger, industrial landowners. They are interested in sound, professional practices for logging, but he said for the most part

they are conservative Republicans who are not interested in environmental messages, which they view as liberal. Thus, Houser and his colleagues tend not to make the connections between good management and benefiting the climate.

Houser’s approach in working with owners is first to establish their own goals for their land and then help them to understand some principles of forest management. For example, he recommends strategic cutting to allow the forest to flourish, and he argues that this is a way to improve the rate of return on the investment, rather than on capturing more carbon through improved growth. It is important for his trustworthiness, he added, that he himself is a forest owner who manages his own land in ways he is recommending to them.

Alton Perry, speaking from the perspective of the North Carolina Forest Service, agreed with the previous comments. North Carolina conducted a forestland assessment in 2007 that examined all aspects of the state’s forest resources as well as the risks posed by climate change. He and other extension workers used the information for education programs. For example, they realized that they had been advocating that trees be planted 622 to the acre, but the result was too dense. Widening the spacing allows for greater plant and wildlife diversity, they found. Like Harris and Houser, he added, he and his colleagues provide information of this sort as part of an effort to support owners in pursuing their own management goals. “As foresters and forest technicians,” he added, “we try to identify sound forest management to help them reach those goals.”

He and his colleagues have also found that owners are wary of government officials who may offer a message but do not stay around to help the owner implement a response. Extension workers gain trust when they are responsive to landowners’ questions, he added. In a climate of limited resources, they have found other agency partners to help support and deliver messages to the landowners. For example, they are working with the Roanoke Electric Cooperative to help guide local forestland owners in addressing forestland management issues.

Amanda Mahaffey, northeast region director for the Forest Guild, described the experience that members of the Forest Guild6 had in working with woodland owners. She agreed with earlier presenters in believing that climate change outreach depends on the contributions of multiple actors. She sees a lot of value in bringing together diverse groups, as the

__________________

6The Forest Guild is an organization of foresters and associated resource professionals who practice and promote sustainable and ecologically based forestry to benefit the forest and the human communities that depend on it. See http://www.forestguild.org/About-Us.html [December 2013].

Roanoke Electric Cooperative has done, to develop a “shared understanding of what can be done for everyone’s mutual benefit.”

Foresters are not generally trained in social communication, media studies, and marketing, Mahaffey noted. Foresters tend to choose their career path because they prefer being alone in the woods to public discussion, she added, but “we have to learn.” Foresters who understand the role of climate change have a responsibility to be “that trusted resource” for other landowners, in Mahaffey’s view. They need the communication tools and strategies that are being discussed at the workshop to meet that objective. Developing the communication skills of the foresters who can spread the word is a goal separate from the goal of reaching new audiences. “We need the psychology and sociology 101 course,” she noted.

Karl Dalla-Rosa, forest stewardship program manager, closed with the perspective of the U.S. Forest Service, highlighting two key aspects of the forest stewardship program. One is communicating to the general public why private forestland is important and the role its owners play in adapting to and mitigating climate change. Recognizing how controversial the issue of climate change remains with some people, though, he believes it may not be the ideal platform for getting out core messages about forest management. The second aspect is engaging the forestland owners themselves. He noted that the workshop presentations seemed to support the direction the forest stewardship program has taken, which the Forest Service calls the landscape stewardship approach.

The agency’s objective is to work with owners proactively to encourage them to take actions that benefit the climate and also support their own objectives for their land. The Forest Service works through existing social structures and communities, he added, to develop an appreciation for the entire landscape, beyond the boundaries of an individual’s property. They have sought out peer-to-peer networks, hoping to leverage the expertise and knowledge landowners already have, following up with professional advice where it is needed. Nothing they would recommend that landowners do, he added, would be “in conflict with what a landowner would do to manage a property for forest health or resilience or those things.”

Dalla-Rosa stated, however, that eventually it is the Forest Service’s responsibility to “relate what we’re doing with that landowner to broader climate change objectives.” Ideally, the service would engage landowners not only in managing their own land responsibly, but also in spreading the word to other landowners about what they are doing and how it relates to climate change.

This page intentionally left blank.